Educating the next generation of world leaders

BRASILIA, Brazil -- During the 1991 Gulf War, the staff at the

School of the Nations here faced a touchy diplomatic problem.

Numerous among the school's students in this modern South American

capitol are the sons and daughters of the various international

diplomats posted here.

That year, the son of the Iraqi ambassador was in attendance --

along with many children from the United States and other countries

in the United Nations-sponsored coalition that intervened to end

Iraq's occupation of Kuwait.

At one point a few of the students made aggressive remarks to

the Iraqi, "about how 'you guys' are going to get 'smashed'

and so forth," said James M. Sacco, the school's director.

"But fortunately, most of the other students rallied around

the Iraqi boy, saying things like 'Here at the school we are all

friends,' and 'Here at the school, nationality doesn't make a

difference,'" said Dr. Sacco.

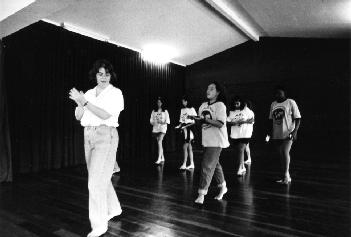

Brasilia has some 85 different foreign embassies, and the School

of the Nations has developed a special reputation as a school where

children from all cultures and countries can come together

comfortably. Shown at left are a group of elementary students, eager

to have their photograph taken.

That incident -- among others -- exemplifies the success of the

school at fulfilling its own distinctive sense of mission: to

raise up a new generation of leaders instilled with the ideal

of world citizenship.

There are some 85 different foreign embassies in Brasilia and

since the school's establishment in 1980 by a group of Bahá'í

educators from the United States and Brazil, it has quietly flourished

by delivering on that promise.

Serving some 230 full-time students from 25 different national

backgrounds in grades kindergarten through eight, the school offers

a distinctive curriculum that blends an emphasis on cross-cultural

experiences with moral and religious education in a bilingual

setting.

Half of the classes are taught in Portuguese and half in English.

In this way, the program not only meets all of the Brazilian government's

curriculum requirements but also satisfies the concerns of diplomats

and others who want their children to be intellectually fluent

in a multi-cultural and interdependent world.

"We were very sympathetic to this kind of philosophy, and

it is one of the main reasons we send our kids to this school,"

said Clemens Birrer, the counsellor of the Swiss Embassy here,

who has two daughters at the school. "My wife and I are convinced

that human relationships have to be built up outside of any context

of color or race or nationality.

"We also feel that human relationships have to be built up

with religious belief, because moral belief influences human relationships."

For this reason, said Counsellor Birrer, he and his wife very

much appreciate the school's attempt to teach about all of the

world's major religions in its curriculum, even though they are

themselves active Catholics.

"How can you build a world citizen if you don't know anything

about Islam, for example?" asked Counsellor Birrer. "Because

Islam is established very much on moral principles. So we agree

to the general education on religion to sensitize the children

to the fact that there is a God and that you can pray."

Indeed, although the school is run by Bahá'ís and

incorporates religion as an element of its curriculum, the administration

and teachers take great pains to teach respect for all of the

world's great religions.

When the school dedicated a new building in 1987, for example,

the ceremonies featured not only Bahá'í prayers,

but also Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu prayers,

all reflecting the various religious backgrounds of the student

body. "In fact, it was the Iraqi boy who read from the Koran,"

said Dr. Sacco.

"We have a complete sequence on comparative religions running

from the 5th through the 8th grade," Dr. Sacco continued.

"It starts with a study of the Bible in a historical context

in the 5th grade, then with the New Testament in the 6th grade,

and then Islam in the 7th grade. In the 8th grade, they study

the Bahá'í Faith and other philosophical and religious

movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Because of this inclusive approach, many Muslim diplomats have

chosen to send their children to the school, choosing it even

over such excellent alternatives as the American School, the French

School or the local Brazilian schools.

"It is important for children to learn about other citizens

and other cultures. My daughter now has friends from Africa, the

United States and from Russia and it is very nice. She also takes her

own culture to the others."

-- Mrs. Emel Eryilmaz

Bil Eryilmaz, a retired Turkish diplomat, and his wife, Emel,

who currently works as the administrative attache at the Turkish

Embassy here, have sent three of their children to the school

and very much appreciate its philosophy of promoting world citizenship.

"It is important for children to learn about other citizens

and other cultures," said Mr. Eryilmaz. "My daughter

now has friends from Africa, the United States and from Russia

and it is very nice. She also takes her own culture to the others."

The Eryilmaz's also appreciate the school's emphasis on religious

toleration. "The children learn how to pray to God and they

learn who is God," said Mr. Eryilmaz.

They are also pleased with the school's academic success. They

said their oldest daughter recently graduated from the school

and returned to Turkey. And despite long years outside of Turkey,

they said, she nevertheless did extremely well in the comprehensive

examinations at her new high school there.

While Dr. Sacco confirmed that students at the school have gone

on to demonstrate a high level of academic achievement, he said

the administration and staff were perhaps the most proud of their

success at instilling a philosophy compatible with today's interdependent

world.

"What sets the School of the Nations apart is really this

aspect of peace education, of education for world citizenship,"

Dr. Sacco said.

"Outsiders have told us that the children from the school

are more outgoing and more willing to make friends and go on to

new experiences.

"We not only teach kids to appreciate diversity, but to seek

it out. Not to be afraid of it," he said. "But of course

that is something that is very hard to measure. You can't score

it. But we feel it is perhaps the most important thing we have

to offer."

(e-mail: 1Country@BIC.Org)

| Contents

| 1994 Issues

(e-mail: 1Country@BIC.Org)

| Contents

| 1994 Issues

(e-mail: 1Country@BIC.Org)

| Contents

| 1994 Issues

(e-mail: 1Country@BIC.Org)

| Contents

| 1994 Issues