Aurangzib took for his title the Persian word engraved on the sword which his captive father had given him – Alamgir, “World-compeller” – and by this title he was known to his subjects and to succeeding generations of Moslems. Before we consider the use he made of his power we must realize something of his character.

Aurangzib was, first and last, a stern Puritan. Nothing in life – neither throne, nor love, nor ease – weighed for an instant in his mind against his fealty to the principles of Islam. For religion he persecuted the Hindus and destroyed their temples, while he damaged his exchequer by abolishing the time-honoured tax on the religious festivals and fairs of the unbelievers. For religion’s sake he waged his unending wars in the Deccan, not so much to stretch wider the boundaries

of his great empire, as to bring the lands of the heretical Shi’a within the dominion of orthodox Islam. Religion induced Aurangzib to abjure the pleasures of the senses as completely as if he had indeed become the fakir he had once desired to be. No animal food passed his lips, and his drink was water; so that, as Tavernier says, he became “thin and meagre, to which the great fasts which he keeps have contributed. During the whole of the duration of the comet [four weeks, in 1665], which appeared very large in India, where I then was, Aurangzib drank only a little water and ate a small quantity of millet bread; this so much affected his health that he nearly died, for besides this he slept on the ground, with only a tiger-skin over him; and since that time he has never had perfect health.” Following the Prophet’s precept that every Moslem should practise a trade, he devoted his leisure to making skull-caps, which were doubtless bought up by the courtiers of Delhi with the same enthusiasm as was shown by the ladies of Moscow for Count Tolstoi’s boots. He not only knew the Koran by heart, but copied it twice over in his fine calligraphy, and sent the manuscripts, richly adorned, as gifts to Mekka and Medina. Except the pilgrimage, which he dared not risk lest he should come back to find an occupied throne, he left nothing undone of the whole duty of the Moslem.

Aurangzib, it must be remembered, might have cast the precepts of Mohammed to the winds and still kept – nay, strengthened – his hold of the sceptre of Hindustan. After the general slaughter of his rivals, his

Cap makers and turban fitters.

seat on the Peacock Throne was as secure as ever had been Shah Jahan’s or Jahangir’s. They held their power in spite of flagrant violations of the law of Islam; they abandoned themselves to voluptuous ease, to “Wein, Weib, and Gesang,” and still their empire held together; even Akbar, model of Indian sovereigns, owed much of his success to his open disregard of the Mohammedan religion.

The empire had been governed by men of the world, and their government had been good. There was nothing but his own conscience to prevent Aurangzib from adopting the eclectic philosophy of Akbar, the luxurious profligacy of Jahangir,

Hindu musicians

or the splendid ease of Shah Jahan. The Hindus would have preferred anything to a Mohammedan bigot. The Rajput princes only wanted to be let alone. The Deccan would never have troubled Hindustan if Hindustan had not invaded it.

Probably any other Moghul prince would have followed in the steps of the kings his forefathers, and emulated the indolence and vice of the luxurious court in which he had received his earliest impressions.

Aurangzib did none of these things. For the first time in their history the Moghuls beheld a rigid Moslem in their emperor – a Moslem as sternly repressive of himself as of the people around him, a king who was

prepared to stake his throne for the sake of the faith. He must have known that compromise and conciliation formed the easiest and safest policy in an empire composed of heterogeneous elements of race and religion. He was no youthful enthusiast when he ascended the throne at Delhi, but a man of forty, deeply experienced in the policies and prejudices of the various sections of his subjects. He must have been fully conscious of the dangerous path he was pursuing, and well aware that to run a-tilt against every Hindu sentiment, to alienate his Persian adherents, the flower of his general staff, by deliberate opposition to their cherished ideas, and to disgust his nobles by suppressing the luxury of a jovial court, was to invite revolution. Yet he chose this course, and adhered to it with unbending resolve through close on fifty years of unchallenged sovereignty. The flame of religious zeal blazed as hotly in his soul when he lay dying among the ruins of his Grand Army of the Deccan, an old man on the verge of ninety, as when, in the same fatal province, then but a youth in the springtime of life, he had thrown off the purple of viceregal state and adopted the mean garb of a mendicant fakir.

All this he did out of no profound scheme of policy, but from sheer conviction of right. Aurangzib was born with an indomitable resolution. He had early formed his ideal of life, and every spring of his vigorous will was stretched at full tension in the effort to attain it. His was no ordinary courage. That he was physically brave is only to say he was a Moghul prince of the old

lion-hearted stock. But he was among the bravest even in their valiant rank. In the crisis of the campaign in Balkh, when the enemy, “like locusts and ants,” hemmed him in on every side, and steel was clashing all around him, the setting sun heralded the hour of evening prayer: Aurangzib, unmoved amid the din of battle, dismounted and bowed himself on the bare ground in the complicated ritual of Islam, as composedly as if he had been performing the rik’a (prostration) in the mosque at Agra. The king of the Uzbegs noted the action, and exclaimed, “To fight with such a man is self-destruction! “

We may read Aurangzib’s ideal of enlightened kingship in his reply to one of the nobles who remonstrated with him on his incessant application to affairs of state: “I was sent into the world by Providence,” he said, as Bernier records his words, “to live and labour, not for myself, but for others; it is my duty not to think of my own happiness, except so far as it is inseparably connected with the happiness of my people. It is the repose and prosperity of my subjects that it behooves me to consult; nor are these to be sacrificed to anything besides the demands of justice, the maintenance of the royal authority, and the security of the state. It was not without reason that our great Sa’di emphatically exclaimed, Cease to be Kings! Oh, cease to be Kings! Or determine that your dominions shall be governed only by yourselves.’” In the same spirit he wrote to Shah Jahan: “Almighty God bestows his trusts upon him who discharges the duty of cherishing his subjects

Aurangzib.

and protecting the people. It is manifest and clear to the wise that a wolf is no fit shepherd, neither can a faint-hearted man carry out the great duty of government.

Sovereignty is the guardianship of the people, not self-indulgence and profligacy.” And these were

not merely fine sentiments, but ruling principles. No act of injustice, according to the law of Islam, at least after his accession, has been proved against him. Ovington, who was informed by Aurangzib’s least partial critics, the English merchants at Bombay and Surat, says that the Great Moghul is “the main ocean of justice. He generally determines with exact justice and equity; for there is no pleading of peerage or privilege before the emperor, but the meanest man is as soon heard by Aurangzib as the chief Omrah (amir), which makes the Omrahs very circumspect of their actions and punctual in their payments.” Khalfi Khan, a native chronicler, tells us that the emperor was a mild and painstaking judge, easy of approach and gentle of manner; and the same character is given him by Doctor Careri, who was with him in the Deccan in 1695. So mild indeed was his rule that “throughout the imperial dominions no fear and dread of punishment remained in the hearts” of the provincial district officials, and the result was a state of corruption and misgovernment worse than had ever been known under the shrewd but kindly eye of Shah Jahan.

Yet his habit of mind did not lend itself to trusting his officials and ministers overmuch, whether they were efficient or corrupt. He was no believer in delegated authority; and the lessons in treachery which the history of his dynasty afforded, and in which he had himself borne a part during the war of succession, sank deep into a mind naturally prone to suspicion. That he lived in dread of poison is only what many

Moghul princes endured; he had, of course, a taster, and Ovington says that his physician had to “lead the way, take pill for pill, dose for dose,” that the emperor might see their operation upon the body of the doctor before he ventured himself. His father had done the like before him. Like him, Aurangzib was served by a large staff of official reporters, who sent regular letters to keep the Great Moghul informed of all that went on in the most distant as well as the nearest districts. He treated his sons as he treated his nobles; imprisoned his eldest for life, and kept his second son in captivity for six years upon a mere suspicion of disloyalty. He had good reason to know the danger of a son’s rebellion, but this general habit of distrust was fatal to his popularity. Good Moslems have often extolled his virtues; but the mass of his courtiers and officers lived in dread of arousing his suspicion, and, while they feared, resented his distrustful scrutiny. Aurangzib was universally respected, but he was never loved.

Simple of life and ascetic as he was by disposition, Aurangzib could not altogether do away with the pomp and ceremony of a court which had attained the pinnacle of splendour under his magnificent father. In private life it was possible to observe the rigid rules and practise the privations of a saint, but in public the emperor must conform to the precedents set by his royal ancestors from the days of Akbar, and hold his state with all the imposing majesty which had been so dear to Shah Jahan. A Great Moghul without gorgeous

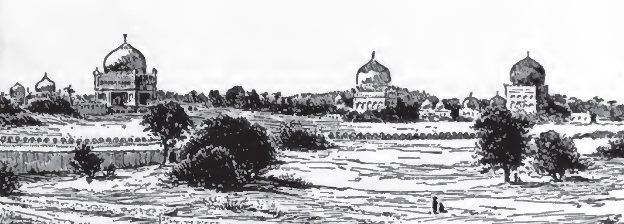

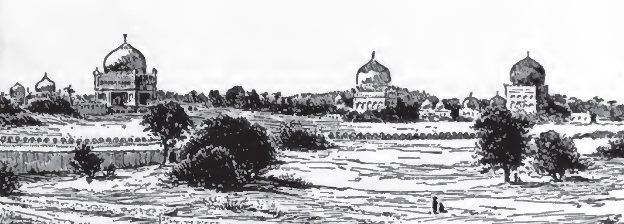

The Jami’ Masjid, or Great Mosque at Delhi.

darbars, dazzling jewels, a glittering assemblage of armed and richly habited courtiers, and all the pageantry of royal state would have been inconceivable or contemptible to a people who had been accustomed for centuries to worship and delight in the glorious spectacle of an august monarch enthroned amid a blaze of splendour. Among Orientals especially the clothes make the king.

The emperor divided his residence between Delhi and Agra, but Delhi was the chief capital, where most of the state ceremonies took place. Agra had been the metropolis of Akbar, and usually of Jahangir, but its sultry climate interfered with the enjoyment of their luxurious successor, and the court was accordingly removed,

at least for a large part of the year, to New Delhi, the “City of Shah Jahan.” The ruins of this splendid capital, its mosques, and the noble remains of its superb palace are familiar to every reader. To see it as it was in its glory, however, we must look through the eyes of Bernier, who saw it when only eleven years had passed since its completion. His description was written at the capital itself in 1663, after he had spent four years of continuous residence there; so we have every reason to assume that he knew his Delhi thoroughly.

The city, he tells us, was built in the form of a crescent on the right bank of the Jumna, which formed its north-eastern boundary, and was crossed by a single bridge of boats. The flat surrounding country was then, as now, richly wooded and cultivated, and the city was famous for its luxuriant gardens. The circuit of the walls was six or seven miles, but outside the gates were extensive suburbs, where the chief nobles and wealthy merchants had their luxurious houses; and there also were the decayed and straggling remains of the older city just without the walls of its supplanter. Numberless narrow streets intersected this wide area and displayed every variety of building, from the thatched mud and bamboo huts of the troopers and camp-followers, and the clay or brick houses of the smaller officials and merchants, to the spacious mansions of the chief nobles, with their courtyards and gardens, fountains and cool matted chambers, open to the four winds, where the afternoon siesta might be

enjoyed during the heats. Two main streets, perhaps thirty paces wide and very long and straight, lined with covered arcades of shops, led into the “great royal square” which fronted the fortress, or palace of the emperor. This square was the meeting-place of the citizens and the army, and the scene of varied spectacles. Here the Rajput rajas pitched their tents when it was their duty to mount guard; for Rajputs never consented to be cooped up within Moghul walls. Beyond was the fortress, which contained the emperor’s palace and mahal, or seraglio, and commanded a view of the river across the sandy tract where the elephant fights took place and the rajas’ troops paraded. The lofty walls were slightly fortified with battlements and towers, and surrounded by a moat, and small field-pieces were pointed upon the town from the embrasures. The palace within was the most magnificent building of its kind in the East, and the private rooms or mahal alone covered more than twice the space of any European palace. Streets opened in every direction, and here and there were seen the merchants’ caravanserais and the great workshops where the artisans employed by the emperor and the nobles plied their hereditary crafts of embroidery, silver and gold smithery, gun-making, lacquer-work, painting, turning, and other arts.

Delhi was famous for its skill in the arts and crafts. It was only under royal or aristocratic patronage that the artist flourished; elsewhere the artisan was at the mercy of his temporary employer, who paid him as he

chose. The Moghul emperors displayed a laudable appreciation of the fine arts, which they employed with lavish hands in the decoration of their palaces. A large number of exquisite miniatures, or paintings on paper designed to illustrate manuscripts or to form royal portrait-albums, have come down to us from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The technique and detail are admirable, and the colouring and lights often astonishingly skilful. They include portraits of the emperors, princes, and chief nobles which display unusual power in the delineation of individual countenances, and there are landscapes which are happily conceived and brilliantly executed. There is no doubt that the Jesuit missions at Agra and other cities of Hindustan brought Western ideas to bear upon the development of Indian painting. Jahangir, who was, by his own account, “very fond of pictures and an excellent judge of them,” is recorded to have had a picture of the Madonna behind a curtain, and this picture is represented in a contemporary painting which has fortunately been preserved. Tavernier saw on a gate outside Agra a representation of Jahangir’s tomb “carved with a great black pall with many torches of white wax, and two Jesuit Fathers at the end,” and adds that Shah Jahan allowed this to remain because “his father and himself had learnt from the Jesuits some principles of mathematics and astrology.” The Augustinian Manrique, who came to inspect the Jesuit missions in the time of Shah Jahan, found, as we have seen, the prime minister, Asaf Khan, at Lahore in a

Lattice in bathroom of Shah Jahan’s palace at Delhi.

palace decorated with pictures of Christian saints. In most Moghul portraits, the head of the emperor is surrounded by an aureole or nimbus, and many other features in the schools of painting at Agra and Delhi remind one of contemporary Italian art.

The artists were held in high favour at court, as we may judge from contemporary native accounts in which art is alluded to, and many of their names have been preserved. Their works added notably to the decoration

The Audience-Hall, Divan-i Aam, at Delhi.

of the splendid and elaborate palaces which are among the most durable memorials of the period.

The scene in the Hall of Audience on any great occasion was almost impressive enough to justify the inscription on the gateway: “If there be a Heaven upon earth, it is here, it is here.” The emperor’s approach was heralded by the shrill piping of the hautboys and clashing of cymbals from the band-gallery over the great gate, and Bernier thus describes the scene:–

“The king appeared, in the most magnificent attire, seated upon his throne at the end of the great hall. His vest was of white and delicately flowered satin, with a silk and gold embroidery of the finest texture. The turban of gold cloth had an aigrette whose base was composed of diamonds of an extraordinary size and value, besides an Oriental topaz which may be pronounced unparalleled, exhibiting a lustre like the sun. A necklace of immense pearls suspended from his neck reached to his stomach. The throne was supported by six massy feet, said to be of solid gold, sprinkled over with rubies, emeralds, and diamonds. It was constructed by Shah Jahan for the purpose of displaying the immense quantity of precious stones accumulated successively in the treasury from the spoils of ancient rajas and Patans, and the annual presents to the monarch which every Omrah is bound to make on certain festivals. At the foot of the throne were assembled all the Omrahs, in splendid apparel, upon a platform surrounded by a silver railing and covered by

a spacious canopy of brocade with deep fringes of gold. The pillars of the hall were hung with brocades of a gold ground, and flowered satin canopies were raised over the whole expanse of the extensive apartment, fastened with red silken cords from which were suspended large tassels of silk and gold. The floor was covered entirely with carpets of the richest silk, of immense length and breadth. A tent, called the aspak, was pitched outside [in the court], larger than the hall, to which it was joined at the top. It spread over half the court, and was completely enclosed by a great balustrade, covered with plates of silver. Its supporters were pillars overlaid with silver, three of which were as thick and as high as the mast of a barque, the others smaller. The outside of this magnificent tent was red, and the inside lined with elegant Masulipatan chintzes, figured expressly for that very purpose with flowers so natural and colours so vivid that the tent seemed to be encompassed with real parterres. As to the arcade galleries round the court, every Omrah had received orders to decorate one of them at his own expense, and there appeared a spirit of emulation as to who should best acquit himself to the monarch’s satisfaction. Consequently all the arcades and galleries were covered from top to bottom with brocade, and the pavement with rich carpets.”

On his birthday Aurangzib maintained the old Moghul custom of being solemnly weighed in a pair of gold scales against precious metals and stones and food, when the nobles one and all came with offerings

An elephant fight at Jaipur.

of jewels and gold, sometimes to the value of £2,000,000. The festivals often ended with the national sport, an elephant-fight. Two elephants charged each other over an earth wall, which they soon demolished; their skulls met with a tremendous shock, and tusks and trunks were vigorously plied, till at length one was overcome by the other, when the victor was separated from his prostrate adversary by an explosion of fireworks between them.

In the jovial days of Jahangir and Shah Jahan, fair Nautch girls used to play a prominent part in the court festivities, and would keep the jolly emperors awake half the night with their voluptuous dances and agile antics; but Aurangzib was “unco guid” and would as soon tolerate idolatry as a Nautch.

Indeed even his wives played but a small part in his life. According to Manucci, the chief wife was a Rajput princess, and became the mother of Mohammad and Mu’azzam, besides a daughter. A Persian lady was the mother of A’zam and Akbar and two daughters. The nationality of the third, by whom the emperor had one daughter, is not recorded. Udaipuri, the mother of his youngest son, Kam Bakhsh, was a Christian from Georgia, and had been purchased by Dara, on whose execution she passed to the harem of Aurangzib.

Even on every-day occasions, when there were no festivals in progress, the Hall of Audience presented an animated appearance. Not a day passed but the emperor held his levee from the window of the jharukha, while the bevy of nobles stood beneath and the common crowd surged in the court to lay their grievances and suits before the imperial judge. The ordinary levee lasted a couple of hours, and during this time the royal stud was brought from the stables opening out of the court and passed in review before the emperor, so many each day; and the household elephants, washed, and painted black, with two red streaks on their foreheads, came in their embroidered caparisons and silver chains and bells, to be inspected by their master, and at the prick and voice of their riders saluted the emperor with their trunks and trumpeted their taslim, or homage.

These gorgeous functions had little interest for Aurangzib. The art of government was his real passion. Of course, with his mixed and jarring population

of Hindus, Rajputs, Patans, and Persians, to say nothing of opponents in the Deccan, his first necessity was a standing army. He could indeed rely upon the friendly rajas to take the field with their gallant followers against the Shi’a kingdom in the Deccan or in Afghanistan, and even against their fellow Rajputs, when the imperial cause happened to coincide with their private feuds. He could trust the Persian officers in a conflict with Patans or Hindus, though never against their Shi’a co-religionists in the Deccan. But he needed a force devoted to himself alone, a body of retainers who looked to him for rank and wealth, and even for the bare means of subsistence. This he found in the species of feudal system which had been inaugurated by Akbar. He endeavoured to bind to his personal interest a body of adventurers, generally of low descent, who derived their power and affluence solely from their sovereign, who raised them to dignity or degraded them to obscurity according to his own pleasure and caprice.

The writings of European travellers are full of reference to these amirs, or “nobles,” as they call them, though it must not be forgotten that the nobility was purely official, and had no necessary connection with birth or hereditary estates. In Bernier’s time there were always twenty-five or thirty of the highest amirs at the court, drawing salaries estimated at the rate of one thousand to twelve thousand horse. The number in the provinces is not stated, but must have been large, besides innumerable petty vassals of less than a thousand horse, of whom there were never less than two

or three hundred at court. The troopers Who formed the following of the amirs and mansabdars were entitled to the pay of twenty-five rupees a month for each horse, but did not always get it from their masters. Two horses to a man formed the usual allowance, for a one-horsed trooper was regarded as little better than a one-legged man. The cavalry arm supplied by the amirs and lesser vassals and their retainers formed the chief part of the Moghul standing army, and, including the troops of the Rajput rajas, who were also in receipt of an imperial subsidy, amounted in effective strength to more than two hundred thousand in Bernier’s time (1659–66), of whom perhaps forty thousand were about the emperor’s person. The regular infantry was of small account; the musketeers could only fire decently when squatting on the ground and resting their muskets on a kind of wooden fork that hangs to them, and were terribly afraid of burning their beards or bursting their guns. There were about fifty thousand of this arm about the court, besides a large number in the provinces; but the hordes of camp-followers, sutlers, grooms, traders, and servants, who always hung about the army, and were often absurdly reckoned as part of its effective strength, gave the impression of an infantry force of two or three hundred thousand men. There was also a small park of artillery, consisting partly of heavy guns, and partly of lighter pieces mounted on camels.

The emperor kept the control of the army and nobles in his own hands by this system of grants of

Gold coin of Aurangzib, struck at Thatta, A.H. 1072 (A.D. 1661–2).

land or money in return for military service; and the civil administration was governed on the same principle. The mansab and jagir system pervaded the whole empire. The governors of provinces were mansabdars, and received grants of land in lieu of salary for the maintenance of their state and their troops, while they were required to pay about a fifth of the revenue to the emperor. All the land in the realm was thus parcelled out among a number of timariots, who were practically absolute in their own districts, and extorted the uttermost farthing from the wretched peasantry who tilled their lands.

The only exceptions were the royal demesnes, and these were farmed out to contractors who had all the vices without the distinction of the mansabdars. As it was always the policy of the Moghuls to shift the vassal-lords from one estate to another, in order to prevent them from acquiring a permanent local influence and prestige, the same disastrous results ensued as in the precarious appointments of Turkey. Each governor or feudatory sought to extort as much as possible out of his province, or jagir, in order to have capital in hand when he should be transplanted or deprived, and in the remoter parts of the empire the rapacity of the landholders went on almost

unchecked. The peasantry and working classes, and even the better sort of merchants, used every precaution to hide such small prosperity as they might enjoy; they dressed and lived meanly, and suppressed all inclinations towards social ambitions.

Whether we look at the military or the civil side of the system, the Moghul domination in India was even more like an army of occupation than the “camp” to which the Ottoman Empire has been compared. As Bernier says, “The Great Moghul is a foreigner in Hindustan: he finds himself in a hostile country, or nearly so; a country containing hundreds of Gentiles to one Moghul, or even to one Mohammedan.” Hence his large armies and his network of governors and landholders dependent upon him alone for dignity and support; hence, too, a policy which sacrificed the welfare of the people to the supremacy of an armed minority. Yet it preserved internal peace and secured the authority of the throne, and we read of few disturbances or insurrections in all the half-century of Aurangzib’s reign. Such wars as were waged were either unimportant campaigns of aggression outside the normal limits of the empire, or were deliberately provoked by the emperor’s tolerance. Mir Jumla’s disastrous expedition against Assam was like many other attempts to subdue the northeast frontiers of India. The rains and the guerrilla tactics of the enemy drove the Moghul army to despair, and its gallant leader died on his return in the spring of 1663. The war in Arakan had more lasting effects. This kingdom had long been

a standing menace to Bengal, and a cause of loss and dread to the traders at the mouth of the Ganges. Every kind of criminal from Goa or Ceylon, Cochin or Malacca, mostly Portuguese or half-castes, flocked to Chittagong, where the King of Arakan, delighted to welcome any sort of allies against his formidable neighbour the Moghul, permitted them to settle. They soon developed a busy trade in piracy, and, as Bernier said,

scoured the neighbouring seas in light galleys, called galleasses, entered the numerous arms and branches of the Ganges, ravaged the islands of Lower Bengal, and, often penetrating forty or fifty leagues up the country, surprised and carried away the entire population of villages. The marauders made slaves of their unhappy captives, and burnt whatever could not be removed.” The Portuguese at Hugli abetted these rascals by purchasing whole cargoes of cheap slaves, and, as we have seen, were punished by Shah Jahan, who took their town and carried the remnant of the population as prisoners to Agra in 1632. But though the Portuguese power no longer availed them, the pirates continued with their rapine, and carried on operations with even greater vigour from the island of Sandip, off Chittagong, where the notorious Fra Joan, an Augustinian monk, reigned as a petty sovereign for many years, after contriving, in some mysterious way, to rid himself of the governor of the island.

When Shayista Khan, Aurangzib’s uncle, came to Bengal as governor in succession to Mir Jumla, he judged it high time to put a stop to these exploits, and

in 1666 the pirates submitted to the summons of the new viceroy, backed by the support of the Dutch, who were pleased to diminish the failing power of Portugal. The bulk of the freebooters were settled under control at a place a few miles below Dhakka, hence called Firengi-bazar, “the mart of the Franks,” where some of their descendants still live. Shayista then sent an expedition against Arakan and annexed it, changing the name of Chittagong into Islamabad, “the city of Islam.” He could not foresee that in suppressing the pirates he was aiding the rise of that future power whose humble beginnings were seen in the little factory established by the English at the Hugh in 1640. Twenty years after the suppression of the Portuguese, Charnock defeated the local militia, and in 1690 received from Aurangzib a grant of land at Sutanati, which he forthwith cleared and fortified. Such was the modest foundation of Calcutta.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()