The war between England and Spain, which had begun in 1739 over commercial and maritime quarrels, was now gradually drawing France into open hostilities with England. But as the English had a larger and more powerful navy, the rupture between the two countries placed France in the dangerous position of holding great transmarine possessions and interests by insecure lines of support and communication. In America and the West Indies the colonial dominions of France were more extensive than those of England; in India there was no great difference as to strength or settlements; and the French had the advantage of a most valuable, though rather distant, base of operations at the islands of Bourbon and Mauritius, with a station on the Madagascar coast.

At Mauritius, Labourdonnais, as governor, had been accumulating naval stores since 1740 and preparing, with the aid and approval of the French government, to fall upon the English merchant vessels or to attack

the English settlements in India. In 1743, however, the Directors of the French East India Company, anxious to preserve neutrality in the East Indies, had procured the despatch of orders which held back Labourdonnais; and although, when war had actually been declared in 1744, he received authority to take the offensive, he was not ready until 1746, when he mustered his fleet at Madagascar and sailed in June for the Coromandel coast. Meanwhile, a squadron sent out from England had appeared in 1745 off Pondicherri, which had a weak garrison and unfinished fortifications. Dupleix, in order to gain time, induced the Nawab of Karnatic to interpose with an order forbidding hostilities within his jurisdiction; and in deference to this prohibition the English commodore was persuaded by the authorities at Madras to suspend his attack. The stormy season compelled him to leave the coast; but when the British fleet returned next year, it was met by the French squadron from the Mauritius.

The English Company now appealed to the Nawab in their turn, but they found him lukewarm; he had not been properly bribed; his own position was insecure; nor was it possible for him in any case to prevent the two hostile fleets from fighting or bombarding each other’s factories on the seashore. After an indecisive naval action, the English ships withdrew to Ceylon. Labourdonnais now landed some two thousand men and Madras was besieged by land and sea, until, in September, 1746, it was surrendered on terms permitting the English to regain their town on payment of a ransom.

The Colombo breakwater, Ceylon

But this compromise was violently opposed by Dupleix, who saw plainly enough that if he was to build up solidly a French dominion in India, he must begin by clearing away the English, and who therefore insisted that the fortifications of Madras should be razed to the ground.

The Nawab of the Karnatic also interposed on his side, professing much indignation at this private war within his sovereignty, and demanding that the town should be given up to him, which Dupleix promised to do. After a sharp quarrel over this question Labourdonnais, whose fleet was shattered by a tremendous storm, sailed back with the surviving ships to Mauritius, leaving the French in temporary possession of Madras, under an agreement, made by Labourdonnais,

that if the ransom were paid, it should be restored to the English within three months.

The next incident was important. Dupleix, who had now three thousand French soldiers at his disposal, and who had been positively ordered by a secret despatch from his government on no account to give up Madras, had not the least intention of relinquishing it either to the Nawab or the English Company. When the Nawab invested the town, Dupleix drove off the native troops so effectually as to establish, at one blow, an immense military reputation for the French in the Karnatic, since the ease and rapidity with which the Nawab’s army was dispersed at this first collision ‘between the regular battalions of Europe and the loose Indian levies proved at once the formidable quality of European arms and discipline.

Dupleix made unsparing and audacious use of his advantage; he declared null and void the agreement with the English, seized all the Company’s property, carried the Madras governor and his officers to Pondicherri, where they figured as captives in a triumphal procession, and despatched a large force against the English fortress of St. David, the only fortified post still held by the English, about twelve miles south of Pondicherri. But the French were surprised in their march, and the expedition was so sharply checked that the troops thereafter lay inactively encamped in the neighbourhood of the fort, which they never succeeded in besieging.

In the meantime, as the English squadron was returning

with reinforcements from Ceylon, Dupleix sent his four ships out of its way to the west coast, so that the sea was now open. When, therefore, in 1747, the French commander, Paradis, was about to move again on Fort St. David, he was stopped by the appearance of the English squadron, which threw supplies and troops into the place and compelled him to retire to the protection of Pondicherri. From this moment the tide turned. In attempting to take Cuddalore by a dashing blow, the French were outwitted by Lawrence and beaten back with loss; Admiral Boscawen arrived with a formidable fleet and fifteen hundred soldiers; and in 1748 Pondicherri was invested by land and sea. But as the French had failed before Fort St. David, so the English failed before Pondicherri; the place was so clumsily besieged by the English and so gallantly defended by the French that the assailants had at last to draw off with serious loss.

In 1749 the news of the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle stopped the fighting in India and restored Madras to the English in exchange for the restitution of Louisburg in North America to the French. The chief outcome of this sharp wrestle between the two Companies at close quarters on a narrow strip of seacoast was a notable augmentation of the French prestige in India, and great encouragement to Dupleix in his project of employing his troops as irresistible auxiliaries to any native prince whose cause he might choose to adopt. He was already in close correspondence with one of the parties in the civil war that was just beginning to

spread over the Karnatic; he took care to keep on foot his disciplined troops, whose decisive value in the field had now been abundantly manifested; he had overawed the neighbouring chiefs, depressed the English credit, and seemed to have struck out with the boldness and perspicacity of political genius the straight way toward establishing a French dominion in the Indian peninsula.

So far as it related to facts and circumstances on the Coromandel coast, his judgment of the situation was correct; the opportunity had come, and Dupleix had discerned the right methods of using it. The Moghul empire had finally disappeared in all the southern provinces; the whole realm was torn by internal dissensions; the Marathas, whose mission it was to prepare the way for a foreign domination by riding down and ruining all the Mohammedan powers, were spoiling the country and bleeding away its strength; the native armies in the south were no better than irregular ill-armed hordes of mercenaries; the coasts lay open and defenceless.

Not only Dupleix, but others (as will be shown later on), were beginning to see the practicability of turning this state of things to the advantage of some European power. But Dupleix had not perceived or taken into account certain larger considerations which inevitably controlled the working out of his ambitious schemes and which soon began to counterbalance his local successes. Any plan of establishing the territorial supremacy of a maritime European power in India must be fundamentally defective and must necessarily suffer from dangerous constitutional weakness so long as it does

not rest upon a secure line of communication by sea. Until this prime condition of stability is fulfilled, the aggrandizement of dominion in a distant land only places a heavier and more perilous strain on the weak supports, and the whole fabric is liable to be toppled over by a stroke at its base.

No quarter is given by French writers to Labourdonnais, who is accused of having thwarted the thoroughgoing designs of Dupleix by the half-hearted measure of holding Madras to ransom, by refusing to cooperate energetically in the extirpation of the English settlements, and by sailing away to Mauritius, so that the coast was left clear for the enemy. On his return to France, he was thrown into the Bastille, where he remained three years, though in the end he was honourably acquitted. His quarrel with Dupleix, who was imperious and uncompromising, may have had much to do with his hasty departure from the Indian seaboard. But it is more than doubtful whether, if Labourdonnais had kept his shattered squadron in those waters, he could have held that command of the sea without which all the triumphs of Dupleix over the petty forts on the coast, or over the loose levies of Indian princes, were radically futile.

However this may be, it soon became evident that success on the land would follow superiority at sea. We have seen that when, after the departure of Labourdonnais, a strong English fleet appeared on the scene, the French ships were obliged to leave the coast, while on land the operations of the French were paralyzed

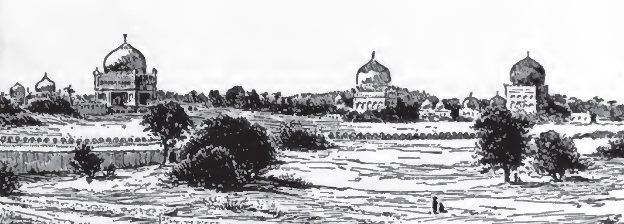

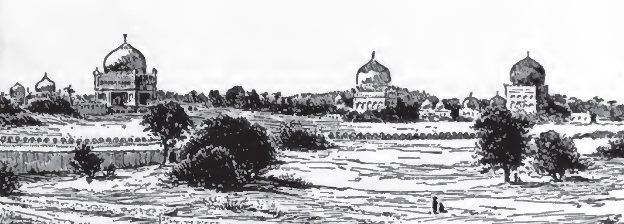

A scene in Pondicherri

at once and they were easily driven back into Pondicherri. Then, also, the restoration of Madras in exchange for Louisburg in North America showed that a mere local advantage counted only as a single move on the vast chessboard, and might promptly be sacrificed to larger combinations.

All these signs and tokens were so many warnings to Dupleix of his insecurity and of the fallacy underlying the fair surface of his designs upon India. But either he missed the significance of sea power, or he committed the mistake of imagining that he could shelter himself from naval attacks by carrying his conquests inland, forgetting that the roots of any European dominion in Asia must always be firmly planted in the fatherland. The experience of this first war seems to have brought him nothing but encouragement,

for as soon as peace had been proclaimed at home, he lost no time in prosecuting his schemes on a larger scale.

We have to remember, in any case, that Dupleix cannot be supposed to have known the relative strength of the maritime nations, or the conditions to which the naval forces of France had been reduced by the war of the Austrian succession. The English had spent immense sums of money, but their navy had greatly increased in power and capacity; it had attained a clear superiority over the French everywhere, and notwithstanding some reverses, it was far more than a match for the enemy in Indian waters. The resources of Holland were exhausted, and she was threatened by imminent invasion when peace was signed at Aix-la-Chapelle. As for France, her victories in the Low Countries had brought her no substantial profit and much positive loss, for the damage done to Holland by the war told entirely in favour of England’s commercial preponderance; while at sea her trade and marine had suffered so heavily, and her naval material at home was so completely spent that, according to Voltaire, she had no warships left.

Such national destitution must have severely affected any great trading enterprise; it was particularly damaging to the interests of the French East India Company which were directly associated with the fortunes of the State. At the end of the war, the Company found themselves deep in debt; their directors, all nominees of the Crown, had been profuse in expenditure,

concealed the real state of affairs and endeavoured to bolster up their credit by magnificent but fictitious dividends, until after 1746 their embarrassments compelled them to make sudden and startling reductions.

The remedy of the French ministers, whenever anything seemed to go wrong with their Company, was to appoint special commissioners to supervise the direction, notwithstanding the Company’s protests that all their misfortunes were due to over-interference. In England, the East India Company’s administration was managed independently by great merchants, with a long traditional experience of Asiatic affairs, with a strong parliamentary connection, with a very extensive business all over the East, and with a large reserve of capital on hand.

In a comparison of the two systems, we have on the French side of the Channel a Company propped up by lottery privileges and tobacco monopolies, subsisting on grants in aid from the treasury. On the English side, we have a rich corporation making annual loans to the government in aid of war expenses, borrowing millions at a very low interest, and using this great financial leverage to obtain from the ministers exclusive privileges and the extension of their charter. In England, the superior wealth and naval instincts of the nation were directed with all the energy and active play of free institutions; in France, the natural ability and enterprise of a courageous and quick-witted people were fatally hampered by a despotic bureaucracy, by

growing financial confusion, and by all the evils of negligent misrule.

To Dupleix in India these things could not be discernible; he saw that his improved position and the increase of his troops gave ample scope to his patriotic ambition; and he now launched out hardily upon the troubled and hitherto unexplored sea of Indian politics. Although the last war had not altered the relative situations of either Company, its effect had been to change their character and to deepen the colour of their rivalry; they had both acquired a taste for Oriental war and intrigue; they had each raised a military force which mutual jealousy prevented them from disbanding, though it was very costly to maintain. The problem of keeping up a standing army without paying for it out of revenue is occasionally solved by an impecunious state at the cost of its neighbours; but there is also the alternative, well known in Indian history, of lending an army for a consideration. The French and English in India could not make direct war on each other while the peace lasted in Europe; they could only prepare for the next rupture by manoeuvring against each other politically, by husbanding their forces, extending their spheres of influence, and. aiming back strokes indirectly at each other under cover of the mêlée that was going on in the country round them.

There was, therefore, everything to invite and nothing to prevent their taking a hand in the incessant fighting for independence and territory among the princes and chiefs who had now discovered the weight of European

metal on the war-field, and were quite ready to pay handsomely for a temporary loan of it. The Companies, indeed, found little difficulty in striking a bargain with men whose best title to rulership was their power to take and hold, whose life and the existence of their principality were continually staked upon the issue of a single battle; capable usurpers with no right; rightful heirs with no capacity; military leaders who had seized a few districts; Maratha captains or Afghan adventurers at the head of some thousand horsemen; provincial viceroys who were trying to found dynasties. None of these rivals could afford to look far ahead or to concern themselves, in the face of emergent needs, with the inevitable consequences of calling in the armed European.

The two Companies, on the other hand, were under an irresistible temptation drawing them toward proposals that offered pay and employment for troops that they could not yet use against each other, with the prospect of large profits upon the campaign, extension of trade privileges or even territory, and the chance of doing some material damage to a rival. It must be admitted that the first who yielded to this temptation were the English, when they took up the cause of a raja who had been expelled by his brother from the Maratha kingdom of Tanjore. But the expedition sent to reinstate him managed matters so badly that the Company were well content to withdraw it on payment of their war expenditure in addition to a small cession of land. This was not only a military failure but a

The main gateway of the Temple at Tanjore

political blunder; since the Tanjore intervention furnished Dupleix with an excellent precedent for taking part in the quarrels of the native rulers precisely at a moment when he was meditating similar designs of a much more important and far-reaching character. He was now ready to develop his policy of assuring the ascendency of France upon a system of armed intervention among the candidates who were preparing to settle by the sword the open question of the succession to rulership in South India.

His opportunity came in April, 1748, with the death of Asaf Jah, the first Nizam, founder of the dynasty that still reigns over a large territory at Haidarabad. Asaf Jah’s succession was disputed between his son

Nasir Jang and his grandson Muzaffar Jang, who both took up arms; whereupon the Karnatic, which had been kept quiet only by Asaf Jah’s power of enforcing his authority, at once became the scene of a violent conflict between rival claimants for the subordinate rulership. The entanglement of these two wars of succession threw all South India into confusion, producing that complicated series of intrigues, conspiracies, assassinations, battles, sieges, and desultory skirmishing that is known in Anglo-Indian history as the War in the Karnatic. The whole narrative, in copious and authentic detail, is to be read in Orme’s History under the title of “The War of Coromandel,” which records the admirable exploits of Clive, Lawrence, and some other stout-hearted but utterly forgotten Englishmen, who at great odds and with small means sustained the fortunes of their country in many a hazardous or desperate situation by their skill, valour, and inflexible fortitude.

Into this medley Dupleix plunged promptly and boldly. His immediate aim was to establish in the Karnatic, the province within whose jurisdiction lay both Madras and Pondicherri, a ruler who should be dependent on the French connection. His ulterior object was the creation of a preponderant French party at the court of the Nizam himself, to whom the Karnatic was still nominally subordinate; and by these two steps he hoped to obtain a firm dominion for his nation in India. In defending himself, afterwards, for having taken a part in these civil broils, he argued, not unfairly, that neutrality was impossible, because if the

French had refused all overtures for European assistance, the contending princes would certainly have got it from the English, who would thus have attained irresistible predominance. However this may be, the result of his policy was that the English Company, who at first expected that the Treaty of 1748 would relieve them from the hostility of France, soon discovered that they were in greater danger than before; for the peace enabled Dupleix to employ his forces in giving such material assistance to Chanda Sahib, one of the competitors for the Karnatic, that the ruling Nawab Anwar-ad-din Khan was speedily attacked, defeated, and slain. The victorious Chanda Sahib joined forces with Muzaffar Jang, who was contending for the Nizamship; and both marched to Pondicherri, where they were magnificently received by the French, to whom they made a substantial grant of territory, with special allotments to Monsieur and Madame Dupleix. The French were now openly supporting Muzaffar Jang for the Nizam-ship of the Deccan, and Chanda Sahib for the Nawab-ship of the Karnatic.

The English, who regarded these proceedings with considerable dismay, although their own behaviour at Tanjore made protest embarrassing, became involved in an acrimonious correspondence with the French, obviously leading to a rupture. Their position, which was now seriously threatened, left them no alternative but to take the side opposed to the French candidates in this double war of succession. When Dupleix sent out a strong contingent in support of Muzaffar Jang, Nasir

Jang, his opponent, appealed to the English, who, after some hesitation, supplied a body of six hundred men and also assisted Mohammad Ali, whom Nasir Jang had appointed to contest the Karnatic Nawabship against Chanda Sahib. Thus Nash. Jang and Mohammad Ali were supported by the English for the Nizamship and the Karnatic against Muzaffar Jang and Chanda Sahib, who were backed by the French.

The English Company also sent home urgent requisitions for succour, representing to their directors that the French had “struck at the ruin of your settlements, possessed themselves of several large districts, planted their colours on the very edge of your bounds, and are endeavouring to surround your settlements in such manner as to prevent either provisions or merchandise being brought to us.” The murder of Nasir Jang by his own mercenaries seemed indeed to secure the triumph of the French cause; for Muzaffar Jang, whom Dupleix was assisting, was thereby placed for the moment in undisputed possession of the Nizamship; while Chanda Sahib with his French auxiliaries became irresistible in the Karnatic, where only the strong fortress of Trichinopoli held out against him.

It would be very difficult to describe briefly and yet clearly the intricate scrambling campaigns that followed, in which the French and English played the leading parts on either side, for the result of every important action depended on the European contingents engaged. While their troops exchanged volleys in the field, the two Companies exchanged bitter recriminations

The rock of Trichinopoli

from Madras and Pondicherri, accusing each other of breaches of international law, denouncing one another’s manoeuvres, and imploring their respective governments at home to interpose against each other’s total disregard of the most ordinary political morality. The French troops had carried the Karnatic for their candidate, had sent Bussy with Muzaffar Jang to establish him as Nizam at Haidarabad, and seemed in a fair way toward general success.

The English had thrown a reinforcement into Trichinopoli, where Mohammad Ali defended himself steadily against Chanda Sahib; but the fortress was beleaguered by a greatly superior army with a strong French contingent, and was saved only when Clive made an effective diversion by his daring seizure of Arcot, the capital of the Karnatic.

This was the turning-point of the war. A large division of the besieging army, despatched from Trichinopoli

Old Bailey Guard at Lucknow

to retake Arcot, made some fierce assaults that were repulsed by the desperate valour of Clive’s scanty garrison, who made such an obstinate stand behind very feeble defences that the attempt had to be abandoned. The English and their allies, led by Clive and Lawrence, then took the open field against their enemy, cut off the French communications, dispersed Chanda Sahib’s army, captured the French officers, and completely relieved Trichinopoli. Chanda Sahib was murdered by the Marathas who had joined Mohammad Ali; and Muzaffar Jang was killed in a skirmish on his march toward Haidarabad.

Meanwhile, Bussy had established himself at Haidarabad, where he had set up a Nizam, had organized a complete corps d’armée under his own command, and had made himself so much too powerful for the native government that he necessarily provoked much jealousy, enmity, and plotting against him. Having succeeded, nevertheless, by great dexterity and firmness in maintaining his position, he obtained from the Nizam an assignment of four rich districts lying along the eastern coast above the Karnatic, still called the Northern Sirkars, which yielded ample revenue for the payment of his troops.

Yet Bussy was well aware that his footing at Haidarabad, far inland, was isolated and precarious, dependent entirely on a semi-mutinous army under a few French officers. He had, therefore, consistently advised making peace with the English; and now the campaign in the Karnatic was visibly turning against

Dupleix, who had no military commander to match: against Clive and Lawrence.

The French leader in India was beginning to find that practice was making the English no worse players than his own side at the game which he himself had introduced. The whole strength of the French had been exerted and exhausted in vain against Trichinopoli; the protracted siege had brought them nothing but disaster. Not only his native allies, but also the French Government at home, were losing their former confidence in Dupleix; for his policy may be said to have broken down when the French candidates for rulership were worsted, and when, after some years of heavy expenditure on these irregular hostilities, the results fell so far short of the expectations that he had raised. Toward the end of 1753, he made overtures for peace, but as soon as the English discovered that he intended to retain in his own person the Nawabship of the Karnatic, they broke off negotiations. As his policy fell into disrepute, he had naturally been led to disguise the real condition of the Company’s finances; so when the directors in Paris were suddenly advised from Pondicherri that they were two millions of francs in debt, they determined at once to recall him.

The English Company at home had long been pressing their government to protest diplomatically against this illegitimate system of private war and against all the Indian proceedings of Dupleix, whose manifest object they declared to be the extirpation of their settlements. They urged that “the trade carried on by

A monolithic temple at Mahabalipur on the South-east coast

the East India Company is the trade of the English nation in the East Indies, and so far a national concern”; that the French power was growing; and that Dupleix had laid claim to the whole south-eastern coast from Cape Comorin to the river Kistna.

The French ministry, on the other hand, did not care to embroil themselves with England, whose sea power was dangerous to all their colonies, on account of these apparently interminable Indian quarrels. Their finances were low; and they had good reasons for honestly desiring to substitute pacific for warlike relations between the two Companies, to discontinue the practice of lending auxiliary troops to native princes, and to agree upon a mutual return to the old commercial business. So

in 1754, having settled an understanding upon this basis with the English government, they deputed to Pondicherri M. Godeheu, who superseded Dupleix, and concluded with the English governor, Saunders, first, a suspension of arms; and secondly, a provisional treaty, afterwards ratified, whereby the Companies bound themselves not to renew attempts at territorial aggrandizement or to interfere in local wars, and covenanted to retain only a few places and districts stipulated in the treaty. Mohammad Ali, whom the English had been supporting throughout the whole contest, was tacitly recognized as Nawab of the Karnatic. This concession virtually dropped the keystone out of the arch upon which the high-reaching policy of Dupleix had been built up, and on his return to France he died, after some vain attempts to obtain justice, in neglect, poverty, and unmerited discredit.

It has been usual to regard this treaty arrangement, which put an end to the unofficial war between the two Indian Companies, as the turning-point of the fortunes of France in the East Indies. The abandonment of the policy of Dupleix has been freely censured as short-sighted and pusillanimous, particularly by recent French writers. The French government is accused of throwing up a game that had been nearly won, and of deserting the hour of his need the man whose genius had engendered the first conception of founding a great European empire in India, who showed not only the possibility of the achievement but the right method of accomplishing it. We are told, for instance, by Xavier

Raymond that. England, in conquering India, has had but to follow the path that the genius of France opened out to her. James Mill, in summarizing the causes why the English succeeded, says that the two important discoveries for conquering India were, first, the weakness of the native armies against European discipline; and secondly, the facility of imparting that discipline to natives in the service of Europeans. He adds: “Both these discoveries were made by the French.” And almost all writers on Indian history have repeated this after him, insisting that the failure of Dupleix is to be ascribed to the ineffective co-operation on the part of the French naval officers, to the want of good military commanders, to accidents, to bad luck at critical moments of the campaign, and, above all, to the faint-heartedness of the French ministry.

Now, it is quite true that Dupleix was a man of genius and far political vision, who strove gallantly against all these obstacles. On the other hand, it is also true that the English, with their usual good luck, had in Clive and Lawrence commanders superior to any of the French military officers with Dupleix, except Bussy. Bussy was a very able man, whom French historians delight to honour; but he was evidently intent, under Dupleix as afterwards under Lally, much more upon building up his own fortunes as a military dictator at Haidarabad than on sharing the unprofitable hard-hitting struggle between the two Companies in the Karnatic; and when misfortune overtook Dupleix and Lally he behaved ungenerously to both of them.

We may heartily agree with Elphinstone that Dupleix was “the first who made an extensive use of disciplined sepoys; the first who quitted the ports on the sea and marched an army into the heart of the continent; the first, above all, who discovered the illusion of the Moghul greatness.” Nevertheless, although it seems invidious to detract from the posthumous glory of a man so able and yet so unfortunate as Dupleix, he cannot be ranked as an original discoverer in Asiatic warfare and politics, without taking into account surrounding circumstances and conditions that naturally pointed to the use of methods which he developed rather than invented.

The weakness of all Oriental states and armies had long been known; and India has always been, through natural causes, less capable than other great Asiatic countries of resisting foreign invasion. Her indigenous population has rarely furnished armies that could encounter the inrush of the hordes from Central Asia; and the only soldiers upon whom the princes of Southern India could rely were commonly mercenaries from the north. At the end of the seventeenth century, the imperial troops were probably still the best in India; but Bernier writes that a division of Turenne’s men would have made short work of the whole Moghul army; nor could any European of military experience have doubted that the loose levies of the Karnatic would be scattered by a few well-armed and disciplined battalions.

Nor was there, in point of fact, any great novelty

in the French introduction of the practice of drilling a few native regiments for their own service. The Moghul army had always contained some European officers, while the Maratha chiefs were forming trained regiments within a very few years after the time of Dupleix; and so soon as the European Companies began to engage in Indian wars, the expedient of giving discipline to the mercenaries who swarmed into their camps was too obviously necessary to rank as a discovery. The real discovery of the value of organized troops had to be made, not by Europeans who knew it already, but by the natives of India, who had never before made trial of such tactics or had met such bodies in the field.

But there is no need to attempt any detraction from the high credit fairly due to Dupleix for having first started on the right road toward European conquest in India. The more interesting question is why, with so much energy, ability, and patriotism, he made so little way. To those who maintain that, but for the blindness of the French government towards the ideas of Dupleix, the blunders of colleagues or subordinates, and the final disavowal of Dupleix, France might have supplanted England in India – the true answer is that these views betray a disregard of historic proportion and an incomplete survey of the whole situation. They proceed on the narrow theory that extensive political changes may hang on the event of a small battle, or on the behaviour of a provincial general or governor at some critical moment. The strength and resources of France and England in their contests for the possession of

A Raja of India receiving a representative of France

Blank page

empires are not to be measured after this fashion, or to be weighed in such nice balances.

It may even be questioned whether the result of the confused irregular struggle between the two Companies in the Indian peninsula told decisively one way or the other upon the final event. The Karnatic war, being unofficial, was necessarily inconclusive, for neither French nor English dared openly to strike home at each other’s settlements; while even if this had been done indirectly through native auxiliaries, the home governments must have interfered earlier. The system of private or auxiliary war gave Dupleix the temporary advantage against the English that it was necessarily confined to the land, where he was the stronger; for as the two nations were at peace, their fleets could not take part in it. On the outbreak of national hostilities three years later, the naval strength of England came into play with decisive effect.

Dupleix was a man of original and energetic political ‘ instincts, and of an imperious and morally intrepid disposition, who embarked upon wide and somewhat audacious schemes of Oriental dominion and lost the stakes for which he played more through want of strength and continuous support than want of skill. He saw that so long as a European Company held its possessions or carried on trade at the pleasure of capricious and ephemeral Indian governments, the position was in the highest degree precarious. The right method, he argued, was to assert independence, to strike in for mastery, and to beat down any European rival who

crossed his path; and, if the English had not been too strong for him, he might have succeeded.

He made the commonplace mistake of affecting ostentatious display and resorting to astute intrigues in his dealing with the Indians; whereas a European should meet Orientals not with their weapons, but with his own. His claim to be recognized as Nawab of the Karnatic, under patents of doubtful authenticity, was a grave political blunder, since it was quite impossible for the English to acquiesce in a position that would have placed their settlements in perpetual jeopardy. Major Lawrence, writing from his camp near Trichinopoli of the negotiations that were attempted in January, 1754, said: “It is my opinion there never can be peace in the province while Dupleix stays in India. He neither values men nor money, nor anything but what can gratify his own ambition. The continual ill-success of his troops would have made anybody but him reflect and be glad of the terms offered; but he talks not like the Governor of Pondicherri but as Prince of the Province.”

Although some allowance must be made for the prejudice of an adversary, there is much truth in this view of the conduct and attitude of Dupleix. We may regard him, nevertheless, as the most striking figure in the short Indian episode of that long and arduous contest for transmarine dominion which was fought out between France and England in the eighteenth century, although it was far beyond his power to influence the ultimate destiny of either nation in India, and although

the result of his plans was, as Clive wrote Lord Bute in 1762, that “we accomplished for ourselves against the French exactly everything that the French intended to accomplish for themselves against us.” It is certain, moreover, that the conception of an Indian empire had already been formed by others besides Dupleix, and that more than one clear-headed observer had perceived how easily the whole country might be subdued by a European power.

It is easy to understand that when France and England, in 1753, determined to stop the fighting between their two Companies in India, they were actuated by the obvious expediency of terminating a protracted war between the representatives of two nations who were at peace in Europe, and of compelling their Indian governors to retire from politics and revert to trade. On the scene of action neither side had as yet gained any decisive advantage. In 1754 the French and English had both received reinforcements that brought their respective European forces up to about two thousand men each; but Orme says that the English troops were so superior in quality to the French that, if hostilities had continued, the English must have prevailed. The presence of an English squadron on the coast was also an argument, he observes, that inclined M. Godeheu toward pacific views.

On the other hand, the French held a much larger territory than the English, and apparently a more considerable political connection among the native states. The English governor at Madras, in transmitting to the

Body-guard of a native prince

London Board the provisional treaty he had made with Godeheu in 1754, warned his Company that the French were in an advantageous position for continuing hostilities; they had, he wrote, a stronger military force – particularly in native cavalry, which could harry the English districts – and “their influence with the country powers far exceeds ours.”

Yet the views and motives by which the French ministers were actuated are amply intelligible. The policy of Dupleix had been frustrated in the sense that, after four years of irregular warfare, he had brought the Company no nearer to the triumphant conclusion

that was to compensate them for heavy military expenditure; while the English Company, though hard pressed, was by no means beaten; their troops were solid and well led, their finances in very fair condition. Dupleix might have gained ground, at best unstable and slippery, among the native princes; but in Europe the English government was remonstrating strenuously, and would certainly go beyond remonstrance whenever it should become manifest to the English people that their Indian trade and possessions were seriously menaced. The headquarters of each rival Company, at Madras and Pondicherri, lay along an open roadstead, completely exposed to attack by sea. The English fleet under Admiral Watson had just reached the coast, and the French government must have been conscious of the inferiority of their own navy. And since the treaty of 1754, which was published in Madras in January of the following year, maintained the French in possession of much larger territory on the Coromandel coast than was awarded to the English – while Bussy was still at Haidarabad with his division of five thousand well-disciplined troops – we may regard the loss of Dupleix himself, and the recognition of Mohammad Ali in the Karnatic, as the only two points in Godeheu’s arrangement that could be said to have placed the French at a distinct disadvantage in India.

The French ministers were actuated, moreover, by the imperious and fundamental necessity of restoring their dilapidated finances; they could not, in justice to their overtaxed people, persist in the unsound and extravagant

system of subsidizing a commercial Company that had plunged into the quicksand of Indian wars. In 1754, the French Company were on the verge of insolvency; their affairs were under official inquiry; they were demanding large subsidies from the treasury; and it was clear that the public credit would suffer seriously if they were allowed to go into liquidation. Dupleix had laid down the principle, which he was endeavouring to impress upon his government, that no Company could subsist in India which had not a fixed revenue from territory to provide for the cost of establishments. But at that time it was an axiom in France, and even in England, that conquest was incompatible with commerce; the opinion of all French authorities, mercantile and administrative, was unanimous against allowing a trading Company to acquire large territory; and these views had for years been impressed sedulously, though in vain, upon Dupleix.

Whether his principle was right or wrong need not be discussed, for the real point is that it was just then impracticable. The exhaustion of the Company’s resources, the embarrassments of French finance, and the weakness of the French navy must have furnished the government with irresistible arguments against persisting in his policy. The true state and inevitable tendency of the contest between the two nations in India has been recognized by M. Marion, in his study of the history of French finance between 1749 and 1754. In defending Machault d’Arnouville, the controller-general of that period, from the imputation of having sacrificed

an empire in Asia by recalling Dupleix, he shows that if the French government had retained his services and supported his policy, the ultimate event could not have been materially changed. The whole fabric of territorial predominance which Dupleix had been building up so industriously was loosely and hastily cemented; it depended upon the superiority of a few mercenary troops, the perilous friendship of Eastern princes, and the personal qualities of those in command on the spot. It was thus exposed to all the winds of fortune and had no sure foundation.

The first thing needful before any solid dominion could be erected by the French in India was to secure their communications with Europe by breaking the power of the English at sea; but this stroke was beyond the strength of the French in 1754. In the last war the French navy had, according to Voltaire, been entirely destroyed; and though since the peace of 1748 it had recovered to some extent, yet we are told that in 1755 France had only sixty-seven ships of the line and thirty-one frigates to set against one hundred and thirty-one English men-of-war and eighty-one frigates. When the Seven Years’ War began in 1756, the French did make a vigorous attempt to regain command of the waterways; and it must be clear that to their failure in that direct trial of naval strength, far more than to their abandonment of the policy of Dupleix, must be attributed the eventual disappearance of their prospects of establishing a permanent ascendency in India.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()