An Indian Rupee of Queen Victoria's reign

Up to this epoch the scene of all the East India Company’s wars had been within India; and for the last fifty years – from the withdrawal of the French in 1763 to the end of the Pindari war in 1818 – the antagonists of the British had been the native Indian powers. As the expansion of England’s dominion carried her so much nearer to foreign Asiatic countries, her rapid approach to the geographical limits of India proper discovered fresh complications for her, and she was now on the brink of collision with new races. The first non-Indian power that provoked her to actual hostility had been the Gurkha chief ship; but as Nepal lies on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, its population belongs, by blood and religion, for the most part to Hinduism. The second non-Indian state that challenged the British from beyond the Indian frontier was the kingdom of a people differing entirely from Indian races, the Burmese.

It is a remarkable coincidence that during the first fifty years occupied by the rise of England’s dominion in India, other rulerships were being founded simultaneously, by a not dissimilar process, around her. In the course of that period (1757–1805) the tribes of Afghanistan had been collected into subjection to one kingdom under the dynasty of Ahmad Shah; the petty Hindu and Mohammedan chiefships of the Panjab had been welded into a military despotism by the strong hand of Ranjit Singh; and the rajas on the lower highlands of the Himalayas had submitted to the domination of Nepal. Lastly, about the time when Clive was subduing Bengal, a Burmese military leader had established by conquest a rulership which had its capital in the plains traversed by the Irawadi River and its principal affluents, from the upper waters of those rivers down to the sea.

The kingdom of Burma, founded in 1757 by Alompra’s subjugation of Pegu, now included not only the open tracts about the Irawadi and the Salwin, extending from the hills out of which these rivers issue to the low-lying seacoast at their mouths, and stretching far southward down the eastern shores of the Bay of Ben-gal. It was absorbing all the mountainous region over-hanging the eastern land frontier of India; and the Burmese armies were pressing westward across the watershed of those mountains through the upland country about the Brahmaputra toward the great alluvial plains of eastern Bengal. There had, consequently, been frequent disputes on that border between the

Burmese warriors

Anglo-Indian and the Burmese authorities, for the dividing-line was unsettled and variable, and on both sides the landmarks had been unavoidably set forward in pioneering fashion, until they were separated only by strips of semi-dependent tribal lands and spheres of influence, from which each party desired to exclude the other. It will be remembered that along all the ranges of the mountains that cut off the Indian plains from the rest of the Asiatic continent, there runs an unbroken fringe of rugged highlands, inhabited by tribes of mixed origin who are more or less warlike and independent.

On the northeast of Bengal lay the kingdom of Assam, with a territory, now part of the British province which bears that name, interposed between the English districts or protectorates and the Burmese dominion. There had been some sanguinary contests

The Government House at Calcutta

for power among princes of the reigning house, and among powerful, ministers who aspired to rule absolutely in the name of one Assamese prince or another, with the inevitable result that the defeated party called in the Burmese from across the mountains eastward. Fresh troubles soon followed, for the king who had been reinstated by the Burmese troops soon quarrelled with them, finding, as usual, that a foreign army of occupation is an exceedingly dangerous remedy for civil war; and the Burmese, after putting several puppets up and down, brought matters to the ordinary conclusion by placing Assam under a governor of their own.

That a feeble and distracted semi-Hindu state on the Anglo-Indian frontier should thus be converted into a province of a warlike and aggressive Indo-Chinese kingdom was by no means to the advantage of the English, with whom it is always a first principle of politics to shut out all strange intruders into India from beyond the mountains or the sea. The Burmese now held the upper waters of that great navigable river, the Brahmaputra, and of other streams flowing from the Assam hills into the sea through Eastern Bengal; they were on the crests of the mountain passes leading into the lowlands, and they were subduing or intimidating all the petty chiefs along our frontier.

It has always been the practice of the English in India, as of other civilized empires in contact with barbarism, to maintain a zone of tribal lands and chief-ships as a barrier or quickset hedge against trespassers

upon their actual frontier by taking these chiefships or little border principalities under their protection. The Burmese were now violating this protectorate in a very menacing fashion. They were engaged in subduing all the northeast corner of India; they had taken Manipur, were making inroads into Cachar, then under British protection, and they had even claimed the British district of Sylhet. In fact they were breaking through all the natural barriers that fence off India by land from Eastern Asia, and were evidently seizing the issues or sally-ports available for sudden descent, whenever and however they might choose, upon the level plains of Bengal. They had seized, not without bloodshed, an island on the British side of the estuary which separated English territory from Arakan.

To be thus openly defied and attacked was a novelty for the English in India, but the Burmese, like the Gurkhas, having never measured themselves hitherto against civilized forces, saw no reason why they should not go on extending their dominion until they had palpably tested a neighbour’s capacity to resist them. When regular hostilities began, there was some very sharp skirmishing on the Assam border, in which the British troops did not always come off victorious; but the despatch of a small army across the Bay of Bengal to attack Rangoon made an effective diversion, for, to a maritime enemy, this was the vulnerable side of the Burmese kingdom. The expedition sent by Lord Amherst, then Governor-General, to Pegu represents the

first campaign undertaken by Anglo-Indian troops on the Asiatic continent beyond India. It ascended the course of the Irawadi; and the Burmese, after an obstinate defence, were compelled to submit to England’s terms. This was a war that produced important and far-reaching consequences for Great Britain, because it carried our arms for the first time beyond the Indian frontier, extended our dominion into a totally different country, and subjected new Asiatic races to our sovereignty. The annexation of Arakan and the Tenasserim provinces placed in English hands almost all that part of the coast which fronts India across the Bay of Bengal, except the maritime province of Pegu, which includes the mouths of the Irawadi River, and which was not annexed until after the war of 1852; and it also threw Burma back over the watershed of the mountain range that runs parallel to this part of the sea-line.

We had now brought a large population, different from the Indians in origin, manners, language, and religion, within the jurisdiction of the Indian empire, and the expansive and levelling forces of European power had been set travelling in a fresh direction upon another line where we were destined to encounter just so much resistance as would compel us to advance by the mere act of overcoming it. A secondary but important consequence of the defeat of the Burmese was their recognition of our protectorate over upper Assam, Cachar, and Manipur, the tract beyond Bengal and along the Brahmaputra River which is now incorporated within

The Golden Throne of Ranjit Singh

the great north-eastern Chief-Commissionership of Assam.

The acquisitions made by the Burmese war had thus effectually sealed up and secured the eastern Anglo-Indian frontier, as the Gurkha war had quieted the only state that could molest the British along the line of the north-eastern Himalayas. When a usurper seized the Bhartpur chiefship in 1826, Lord Combermere took by assault the strong fortress of Bhartpur, before which Lord Lake had failed in 1805. Within India there were now actually only two sovereign powers, the English and the Sikhs; for the Amirs of Sind scarcely fell within the category of Indian rulers. Ranjit Singh, under whom the Sikh domination in the Panjab reached its climax early in the nineteenth century, had acquiesced, after some indications of hostility, in the policy of maintaining friendly relations with the British government. In 1809 he had consequently signed a treaty that confined his territory to the north and west of the Sutlaj River, with the exception of a strip of country on the south bank, in which he was bound not to place troops. This exception had important consequences later; but the broad line of demarcation between the two states

was the river, and this arrangement preserved unbroken for nearly forty years the peace of the northern Anglo-Indian frontier.

The Governor-Generalship of Lord William Bentinck has the distinctive characteristic of representing a period of brief and rare tranquillity in Anglo-Indian history; it was an era of liberal and civilizing administration, of quiet material progress, and of some important moral and educational reforms. Lord Amherst, whom Lord Bentinck succeeded, had just closed a costly and troublesome Burmese war; and with Lord Auckland, who followed him, began the disastrous British campaigns in Afghanistan. Between Amherst and Auckland came an interval of calm rulership that was well employed in the work of domestic improvements and internal organization, favoured by the current of public opinion and political discussion in England. The liberal spirit which had accomplished the enfranchisement of Roman Catholics at home, and which was insisting on Parliamentary Reform, had to some extent influenced the views of Englishmen toward India. The expiration of the term of the East India Company’s charter and the debate over its renewal had drawn attention to Indian affairs; and the act which was passed in 1833 to prolong the charter removed the last vestige of the Company’s commercial monopoly, and finally completed the transformation of the old trading corporation into a special agency for the government of a vast Asiatic dependency.

It was Lord William Bentinck who issued, a few

Lord William Bentinck

months before his term of office expired, the resolution which finally decreed that English should be the official language of India. This important state paper is based on Macaulay’s famous minute, in which he utterly routed the party that still held to the system of promoting learning and literature in India through the medium of Oriental languages.

The controversy arose out of a question as to the distribution of educational grants from the public purse; and Macaulay argued victoriously in favour of English as the language which gives the key to all true knowledge, and as the only proper means of pursuing the higher studies. Lord William Bentinck thereupon issued orders, in accordance with Macaulay’s view, that were received with some doubt and demur on their arrival in England.

It seems to have been James Mill, then an influential officer at the India House, who drafted a formidable censure upon Bentinck’s proceedings, laying stress upon the impolicy of forcing upon the natives of India, by an abrupt reversal of educational policy, a superficial kind of English culture that would be used as a pass-port to public employ rather than as a channel for the acquisition of solid knowledge. Mill and Macaulay were old antagonists, and Macaulay evidently thought the Orientalists talked insufferable nonsense; nevertheless, it can hardly be said, on retrospection, that the weight of argument was altogether on his side. The letter appears never to have been issued; the higher education became almost exclusively English; and as all restrictive press laws were abolished very soon afterwards, the new policy soon produced important and far-reaching consequences.

But the chief title of this Governor-General to posthumous fame rests on the act which he had the courage to pass for putting an end to the burning of Indian widows2. In these days such a measure may appear obviously just and necessary; but in 1829 it was not adopted without much hesitation and many misgivings, for the real nature of public opinion on such subjects among the natives of India was then very imperfectly understood. The point at which law will be supported by natural morality in overruling superstitious sanctions is always difficult to discover; but we know that law and morality have a very complex interaction upon

each other, so that what the positive law refuses to tolerate often becomes immoral, and what morality condemns the law has to denounce. It may be guessed that inhuman or scandalous rites are never really popular, while it is certain that whenever a civil ordinance takes its stand upon an indisputable ethical basis, religion has to give way. The crime was prevalent chiefly among the docile and habitually submissive races of Lower Bengal, and the Governor-General rightly inferred that its peremptory suppression, far from involving political danger, would be accepted as a welcome liberation.

Of Lord William Bentinck’s foreign policy there is not much to be said. He was the first – indeed, he has been the last – Governor-General in whose time unbroken peace has been given to British India, if we exclude the despatch of troops to put down local insurrections in Mysore and in Coorg. In the management of some troublesome business with Haidarabad and the Rajput states he could rely on the skill and experience of Sir Charles Metcalfe; and he adjusted with success the much more important question of English diplomatic relations with Ranjit Singh, the ruler of the Panjab. But his commercial treaty with Ranjit Singh and his convention with the Amirs of Sind for opening the Indus River to British commerce were, in point of fact, the preliminary steps that led the British, a few years later, out upon the wide and perilous field of Afghan politics. The possibility of the overland invasion of India and the question of the

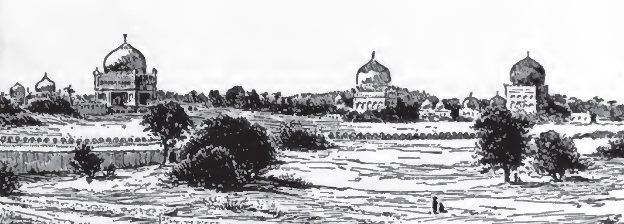

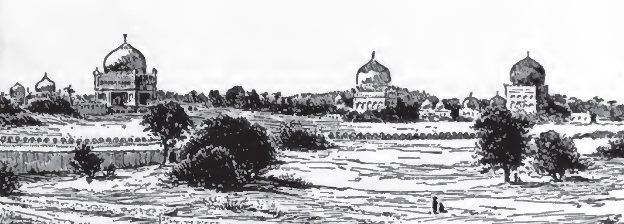

On the Northern Indian Border

measures necessary for the security of the north-western frontier were now occupying the minds of India’s rulers; and the discussion was beginning that has never ended since.

Beyond the Panjab, on the farther side of the Afghan mountains, there were movements that were reviving the ever sensitive apprehensions of insecurity in India. The march of Russia across Asia, suspended by the Napoleonic wars, had latterly been resumed; her pressure was felt throughout all the central regions from the Caspian Sea to the Oxus; and by the treaty of Turkmantchai in 1828 she had established a preponderant influence over Persia.

From that time forward our whole policy and all our strategic dispositions upon the north-west frontier have been directed toward anticipating or counteracting the movements or supposed intentions of Russia. To the English diplomatists of that day it seemed as if our original line of confederate defence had been drawn too widely, because Persia’s discomfiture had proved that we had no means of upholding her integrity against Russian attack. So we negotiated in 1828 a release from our treaty obligations to aid Persia in resisting aggression, and we fell

back upon Afghanistan as our defensible barrier. It followed that, as England receded, Russia pressed on, occupied the diplomatic ground that we had vacated, and converted the Persian power into an instrument for the furtherance of her own interests, which were not ours.

As Persia had just ceded to Russia some districts in the north-west, she was encouraged, by way of compensation, to revive a long-standing claim upon territory belonging to Afghanistan across her north-eastern borders. In 1837, therefore, the Shah of Persia, who claimed Western Afghanistan as belonging of right to his crown, was preparing for an attack upon Herat, the chief frontier city of the Afghans on that side, and the key to all routes leading from Persia into India. Some of the leading Afghan Sirdars were in correspondence with the Persian king; and Shah Shuja, the hereditary prince, who had been driven out by a new Afghan dynasty, was an exile in the Panjab, whence he made unsuccessful attempts to recover his throne, soliciting aid both from the Sikhs and the English.

Shah Shuja represented the legitimate line of descent from Ahmad Shah Abdali, who had created the Afghan kingdom, but a few years before this time his family had been supplanted by the sons of a powerful minister. This is a well-known form of dynastic changes in Asia, produced by the natural tendency of rulership to fall out of the hands of those who cannot keep it into the grasp of those who can. It will be remembered that the royal house of the Maratha empire

had been evicted in the eighteenth century by a ministerial dynasty, the Peshwas; and in the nineteenth century a precisely similar revolution took place in Nepal.

The cardinal point of the whole Asiatic question was now becoming fixed in Afghanistan. From its situation, its natural strength, and its high strategic value, this country has been always a position of the greatest importance to the rulers of India, and the claims of Persia brought it prominently into the political foreground. The British government at home laid down the principle, big with momentous consequence, that the independence and integrity of Afghanistan were essential to the security of India; and missions from India had already explored the Indus and been received by the Amir Dost Mohammad at Kabul. When, therefore, the Shah of Persia in person, attended by some Russian officers, led an army against Herat in 1837, and when the Afghan Amir, disappointed in his hopes of an English alliance, was negotiating with a Russian agent, it will be easily understood that all the elements of alarm and mistrust drew speedily to a head. An English expedition to the Persian Gulf occupied the island of Kharak and made a demonstration against Southern Persia that was quite sufficient to provide the Shah with a good excuse for retiring from Herat, where his assault on the town had failed and where his supplies were scanty.

But the withdrawal from Herat by no means fulfilled views, now prevalent both in England and India, with

regard to the British system of precautionary defence. In London the ministers had declared that “the welfare of our Eastern possessions require that we shall have on our western frontier an ally interested in resisting aggression, in the place of chiefs ranging themselves in subservience to a hostile power”; and they had pressed Lord Auckland to take decisive measures in Afghanistan. The Governor-General proceeded to conclude, with the full approbation of the English ministry, a tripartite treaty, by which the British government and Ranjit Singh covenanted with Shah Shuja to reinstate him in Afghanistan by force of arms. Lord Auckland declared that the unsettled state of that country had produced “a crisis which imperiously demands the interference of the British government,” and that he would continue to prosecute with vigour his measures for the substitution of a friendly for a hostile power in the eastern Afghan provinces, and for “the establishment of a permanent barrier against schemes of aggression on our north-west frontier.” In 1838 a British army marched through Sind up to the Baluch passes to Kandahar, with the avowed object of expelling Dost Mohammad, the ruling Amir, and of restoring Shah Shuja to his throne at Kabul.

This, then, was the position of the English dominion in India at the opening of Queen Victoria’s memorable reign. The names of our earlier allies and enemies – the Nizam, Oudh, the Maratha princes, and the Mysore State – were still writ large on the map, but they had fallen far into the rear of our onward march; while

The relief of Lucknow by Sir Henry Havelock

in front of us were only Ranjit Singh, ruling the Panjab up to the Afghan hills, and the Sind Amirs in the Indus valley. The curtain was just rising upon the first act of the long drama of Central Asian politics, not yet ended in our own time. What did this new departure imply? Not that we had any quarrel with the Afghans, from whom we were separated by the five rivers whose floods unite in the Indus. It meant that, after half a century’s respite, the English believed themselves to be again in danger of contact with

a rival European influence on Asiatic ground; and that, whereas in the previous century they had to fear such rivalry only on the seacoast, they now had certain notice of its gradual approach overland, from beyond the Oxus and the Paropamisus.

The story of the first British campaign in Afghanistan is well known. Shah Shuja was easily replaced on the throne, and the English remained in military occupation of the country round Kabul and Kandahar for about two years. But the whole plan had been ill-conceived politically, and from a strategic point of view the expedition had been rash and dangerous. The base of British operations for this invasion of Afghanistan lay in Sind, a foreign state under rulers not well affected toward the English; while on our flank, commanding all the communications with India, lay the Panjab, another foreign state with a numerous army, watching our proceedings with vigilant jealousy. Such a position was in every way so untenable, and the advance movement was so obviously premature, that no one need wonder at the lamentable failure of our first attempt to extend the British protectorate beyond the limits of India.

The occupation of their country by a foreign army was profoundly resented by the free tribes of Afghanistan, whose patriotism equals their fanaticism, and who have always fought resolutely for their national independence. On his first reappearance among his countrymen Shah Shuja was welcomed to some extent, but it was quite certain that whatever popularity might

accrue to him as their ruler by birthright would rapidly decrease if his throne continued to be surrounded and supported by English troops; for the aphorism that one can do anything with bayonets except sit upon them has much truth even in Asia.

Probably the best course that could have been taken would have been to withdraw the British army, leaving Shah Shuja to rely upon his personal influence, on the fact that he held possession, and on the disciplined local regiments that had been raised for his service. But Lord Auckland had proclaimed, as one main object of his expedition, the establishment of the integrity and independence of Afghanistan; and it was obvious that this was not to be made very sure by leaving Shah Shuja in charge of the country. Yet this chance of success, though precarious, was really the only one, for the alternative was to prolong the military occupation of a mountainous region with a severe winter climate, where supplies are scarce and communications so difficult that combined operations from one centre are constantly interrupted, among a people who pass their lives in guerrilla warfare.

This alternative, however, was unluckily adopted. Sir William Macnaghten, the chief political authority, had heard that the Russians were marching from Oren-burg or Khiva, and that Dost Mohammad, the Amir whom the British had expelled, was hovering about the northern provinces, while the outlying districts were still unruly. Macnaghten accordingly determined to consolidate the Shah’s government before he retired.

But the attempt to raise a kind of standing army for the Amir stirred up fatal jealousies among all the powerful chiefs of the Afghan clans, who, like feudal nobles and free folk everywhere, defer to a king, but detest a master. Disaffection grew and spread, until, in 1841, partial revolts and local risings culminated in universal insurrection. The supplies of the English troops ran short; they had been wearied out by incessant skirmishing; they were under an incapable commander; their outposts were besieged or cut off; and Macnaghten, hoping vainly for a turn of fortune, delayed evacuation of Kabul until the winter had set in. Then, when retreat became inevitable, a series of inconceivable blunders led to the destruction of the whole British force in their passage through the defiles between Kabul and Jalalabad. Nevertheless, the fort at the latter place was gallantly held until it was relieved, in the autumn of 1842, by General Pollock, who marched up to Kabul and reoccupied the city; while at Kandahar General Nott baffled all the attempts of the Afghans to dislodge him.

But in 1841 the Whig ministry, who were the authors of the policy of intervention in Afghanistan, had been displaced, and early in 1842 Lord Ellenborough succeeded Lord Auckland as Governor-General. He issued orders at once for the withdrawal of all British troops from Kandahar and Jalalabad; nor would the British government have escaped the discredit of a hasty and somewhat dishonourable retirement if the military commanders had not taken upon themselves

the responsibility of bolder measures. By the end of 1842, nevertheless, all the English forces had been quietly brought away. Dost Mohammad had been restored to power in Kabul, the country had been evacuated, and the policy of bringing Afghanistan within the sphere of British influence, which was now definitely abandoned, lay dormant until it was successfully revived, under very different conditions, nearly forty years afterward.

In 1839 the territory of the Amirs of Sind, in the valley of the Indus, had been brought within the political control of the British by Lord Auckland, who needed it as a stepping-stone and as a basis for his operations toward South Afghanistan. The port of Karachi, near the Indus mouth, had been seized, and the river had been thrown open to British commerce. When Lord Ellenborough determined to retire from Afghanistan, he was very reluctant to give up the valuable position that we had taken up in Sind; he desired, on the contrary, to acquire permanent possession of the stations that our troops had occupied temporarily, and he took advantage of delay in the payment of tribute to press for territorial cessions. Sir Charles Napier, who had been sent to Sind as a congenial representative of demands that were likely to produce war, submitted to the Governor-General a memorandum arguing that, while we were bound to insist on the rigid observance of treaties, yet such strict punctilio would confine us permanently within the limits of the stations which the treaty assigned to us, and would.

Sir Charles Napier

thus prevent us from interposing for the general good of the Sind people. “Is it possible,” he asked, “that such a state of things can long continue?” and “if this reasoning is correct, would it not be better to come to results at once,” by annexing the places which we now hold temporarily? Proceeding to consider “how we might go to work in a matter so critical,” he enclosed a memorandum of five cases in which the Amirs “seemed to have departed from the terms or spirit of their engagements,” and he urged that it would not be harsh, but on the contrary humane, to coerce them into ceding the places required.

Accordingly, Sir Charles Napier was empowered by Lord Ellenborough to press upon the Sind rulers a new treaty, framed on the basis of exchanging tribute for territory. The Amirs signed it, but mustered their troops and attacked the British Residency at their capital; whereupon Sir Charles Napier marched into their country and gained a decisive victory over their army at Miani in February, 1843. The results were the deposition of the Sind Amirs, and the transfer of the lower Indus valley to the British dominion, whereby we obtained possession of Karachi and the Indus estuary

and brought the whole unbroken circuit of the Indian seacoast within our control. In 1844, however, Lord Ellenborough’s administration was terminated by his recall, and he was succeeded by Sir Henry Hardinge.

In the meantime, from the date of Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, the Sikh government of the Panjab, which had lasted barely thirty years, had been rapidly falling into dilapidation. One chief after another had assumed the administration and had been overthrown or assassinated. In Asia a new kingdom is almost always founded by some able leader with a genius for military organization, who can raise and command an effective army, which he employs not only to beat rivals in the field but also to break down all minor chiefships, to disarm every kind of possible opposition within his borders, and generally to level every barrier that might limit his personal authority. But he who thus sweeps away all means of resistance leaves himself no supports, for support implies the capacity to resist; and the very strength and keenness of the military instrument that he has forged renders it doubly dangerous to his successors. If the next ruler’s heart or hand fail him, there is no longer any counterpoise to the overpowering weight of the sword in the political balance, and the state of the dynasty is upset.

The Sikh dominion had been established in the spirit of religious brotherhood and revolt against Mohammedan oppression; and while such popular, almost democratic forces were immensely strong when condensed

The battle of Miani, at which Napier defeated the Amirs (Feb 17. 1843)

Blank page

into driving power for a well-handled military despotism, they were certain to become ungovernable and to explode if any error or weakness were shown in guiding the machine. None of Ranjit Singh’s sons, real or reputed, had inherited his talents, nor could they manage the fierce soldiery with whom he had conquered the Panjab, driven the Afghans back across the Indus into their mountains, and annexed Kashmir. His eldest and authentic son, Kharrak Singh, died within a year; his reputed son, Sher Singh, the last who endeavoured to maintain his father’s policy of friendship with the British, was soon murdered with his son and the prime minister. The chiefs and ministers who endeavoured to govern after Sher Singh’s death were removed by internecine strife, mutinous outbreaks, and assassinations.

The Sikh state was on the verge of dissolution by anarchy, for all power had passed into the hands of committees of regimental officers appointed by an army that was wild with religious ardour, and furiously suspicious of its own government. The queen-mother, Ranjit Singh’s widow, and her infant son Dhulip Singh were recognized as nominal representatives of the reigning house; but they were liable at any moment to be consumed by the next eruption of sanguinary caprice, and their only hope of preservation lay in finding some outlet abroad for the forces which had reduced the Sikh state to violent internal anarchy. For this purpose it was manifestly their interest to launch their turbulent army across the Sutlaj against

the English, and thus provoke a collision that would certainly weaken and probably destroy it. The military leaders were not blind to the motives with which they were encouraged to march upon the English frontier; but their patriotism had been excited by rumours of the advance of the British army, for Sir Henry Hardinge, the Governor-General, fearing some disorderly inroad, was bringing up troops to reinforce his outposts. There had also been some inopportune frontier disputes, which had embittered the Lahore government, not altogether unreasonably, against the English.

When, therefore, the Sikh soldiers were taunted with questions whether they would tamely submit to European domination, they answered by crossing the Sutlaj River, which was the strategical frontier, and intrenched themselves on the south-eastern bank, in territory, which, though it belonged to Lahore, the Lahore government was bound by treaty not to enter with any considerable armed force. This was taken to be an act of war, and in December, 1845, the Sikhs were met by the British army. On our side the preparations were incomplete; for we had undervalued both the strength and the activity of the enemy; and we had been so long accustomed to easy victories on the open plains of India that the resolute defence of their field-intrenchments made by the Sikhs, and their well-served artillery, took us by surprise.

In the first battle, at Mudki on December 18, 1845, we paid dearly for our success; and three days later, at Firozshah, began the most bloody and obstinate contest

The battle of Mudki, at which Hardinge defeated the Sikhs (Dec 18, 1845)

Blank page

ever fought by Anglo-Indian troops, at the end of which the English army was left in bare possession of its camping-ground, and in a situation of imminent peril from the approach of the Sikh reserves under Tej Singh. But the English maintained a bold front; Tej Singh retired; and in the two battles that followed at Aliwal and Sobraon – the latter fought on February 10, 1846 – the Sikhs, fighting hardily and fiercely, were driven back across the Sutlaj and compelled to abandon further resistance in the field. The Governor-General occupied Lahore in February, 1846, with twenty thousand men; Ranjit Singh’s infant son was placed on the throne under English tutelage; some cessions of territory were exacted; the Sikh army was reduced; and for two years the Panjab was administered as a state under the general superintendence and protection of the British government.

But the expedient of placing the machinery of native government under temporary European superintendence can succeed only when the irresistible authority of the superintending power is universally felt and recognized. The system is unstable because it does not pretend to permanence; it lacks the direct and weighty pressure required to keep down the smouldering elements of military revolt. Although the Sikhs numbered not more than one-sixth of the population of the Panjab, they were united by the recollection of ruler-ship; and the fighting men, who were justly proud of having played an even match against the English, were not yet inclined to settle down again to peaceful agriculture.

At the Lahore court intrigue and jealousies prevailed; and in the outlying districts there was more than one focus of discontent.

The assassination of two British officers at Multan. in April, 1848, was the signal for an insurrection that led to a general rising of the military classes, a reassemblage of the old Khalsa Sikh army, and a second trial of strength with the British troops. In January, 1849, the English general, who displayed very little tactical skill, lost twenty-four hundred men and officers before he won the day at Chilianwala; but in the following month the Sikh army, after a stubborn combat, was at last overthrown by so shattering a defeat at Gujarat that the English were left undisputed masters of the whole country.

These transactions followed the natural course of events and consequences. Contact had produced collision, and collision had terminated in the overthrow of an unstable and distracted government. The English had thus been compelled to break down with their own hands the very serviceable barrier against inroads from Central Asia that had been set up for them by the Sikhs fifty years earlier in North India. It was impossible for the British to leave the country vacant and exposed to an influx of foreign Mohammedans; and it had become a matter of growing importance that England should have the gates of India in her own custody; for the line of Russian advance toward the Oxus, though distant, was declared; and in the last war the Afghans had joined the Sikhs as auxiliaries.

The Battle of Aliwal, in which Smith was victorious over the Sikhs (Jan 28, 1846)

Blank page

That Lord Dalhousie, who was Governor-General from 1848 to 1856, determined, after mature deliberation, against renewing the precarious experiment of a protected native rulership in the Panjab, must now be acknowledged to have been fortunate; for if there had been a great independent state across the Sutlaj when the Anglo-Indian sepoys revolted, eight years later, the Sikhs might have found the opportunity difficult to resist. Before the commencement of hostilities with the British in 1845 they had made several attempts to shake the loyalty of the native army; nor had the spectacle of the Sikh soldiery overawing their government and dictating their own rate of pay been absolutely lost upon all the British sepoy regiments. The Governor-General’s proclamation of 1849, annexing the Panjab to the British crown, carried England’s territorial frontier across the Indus right up to the base of the Afghan hills, finally extinguished the long rivalship of the native Indian powers, and absorbed under British sovereignty the last kingdom that remained outside the pale of the Anglo-Indian empire.

After this manner, therefore, and with the full concurrence of the English nation as expressed through its Parliament, successive Governors-General have pushed on during the nineteenth century by forced marches to complete dominion in India, fulfilling Lord Clive’s prophecy and disproving his forebodings. The long resistance to universal British supremacy culminated and ended in the bloody but decisive campaigns against the Sikh army. Henceforward all English campaigns

Finding the Colours of the 24th Regiment after the Battle of Chilianwala (Jan 13, 1849)

against Asiatic powers were to be outside and around India; for the consolidation of the British empire as a state of first-class magnitude, extending from the sea to the mountains, disturbed all neighbouring rulerships within the wide orbit of its attraction, and affected the whole political system of Asia.

Lord Dalhousie had scarcely reduced the Panjab and planted the British standard at Peshawar, when he became involved in disputes with the Burmese kingdom which led to an important annexation of territory in the southeast. The government of Burma, which has always been as obstinate and foolhardy in its dealings

with foreigners as the Chinese have been far-seeing and comparatively temperate, refused either apology or indemnity for the injurious treatment of British subjects by its officers. Yet the Burmese war of 1826 ought to have convinced less intelligent rulers that they were at the mercy of a strong maritime power in the Bay of Bengal, which could occupy their whole seaboard, blockade their only outlets, and penetrate inland up the Irawadi River. These steps, in fact, the Governor-General found himself compelled to take, with the result that Pegu, a country inhabited by a race that the Burmese had subdued, easily fell into British hands, and was retained when the Burmese armies had been defeated and driven out, its annexation being officially proclaimed December 20, 1852.

This conquest made the British possessions continuous along the eastern shores of the Bay of Bengal, and once more placed the English in a position of the kind which seems to have been peculiarly favourable everywhere to the expansion of dominion. The possession of a flat and fertile deltaic province at the outflow of a great river, whether in Asia or in Africa, enables a maritime power to settle, itself securely on the land with a base on the sea; it gives control of a great artery of commerce, and provides an easy waterway inland. With these advantages, especially as the people of such a province are usually industrious and unwarlike, an enterprising intruder is easily carried up-stream by the course of events, and to this general rule British progress in Burma certainly affords no exception. As the

The fort and harbour of Karachi

English settlement at Calcutta, upon the Ganges estuary, led to the conquest of Bengal; as the occupation of Karachi near the Indus was followed by the taking of Sind; and as the British position at Cairo necessitates a frontier in Upper Egypt, so the planting of a new British capital at Rangoon, near the mouth of the Irawadi, was a first step toward a march up the river to Mandalay.

Having conquered two provinces on two diametrically opposite frontiers of the empire, Lord Dalhousie turned his attention to the interior. When the power of the Maratha Peshwas was extinguished in 1818, the titular Maratha king, Sivaji’s descendant, had been released from his state prison, and the principality of Satara had been conferred on him by Lord Hastings. In 1848, on the death of his successor without heirs, Lord Dalhousie refused to sanction the adoption of an heir. He laid down the principle that the British government is bound in duty as well as in policy to take

possession of a subordinate state that has clearly and indubitably lapsed to the sovereignty by total failure of heirs natural, unless there should be some strong reason to the contrary. Satara was accordingly absorbed; Jhansi followed in 1853; and in 1854 came the lapse of Nagpur, when Lord Dalhousie emphatically declared that “-unless I believed. the prosperity and the happiness of its inhabitants would be promoted by their being placed permanently under British rule, no other advantage which could arise out of the measure would move me to propose it.”

There has never been any doubt about the recognized principle of public policy, based on long usage and tradition, that no Indian principality can pass to an adopted heir without the assent and confirmation of the paramount English government. Lord Dalhousie did not deny that succession might pass by adoption, but he claimed and exercised the prerogative of refusing assent, on grounds of political expediency, in the case of states which, either as the virtual creation Of the British government, or from their former position, stood to that government in the relation of subordinate or dependent principalities. And if he withheld assent, the state underwent incorporation into British territory by lapse. Nothing, thought the Governor-General, could be more fortunate for the subjects of a native dynasty than its extinction by this kind of political euthanasia.

It may be worthwhile to add here that this doc-trine of lapse is now practically obsolete, having been

The Massacre Ghat at Cawnpur

On June 27,1857, the banks of the Ganges at Cawnpur were the scene of a massacre of more than three hundred British by the natives, who, headed by Nana Sahib, had risen in rebellion against the foreigners. Relying upon a promise, of safe conduct, some four hundred and fifty of the English, men, women, and children, had prepared to leave Cawnpur and embarked at the Safi Chaura Ghat. No sooner were they in the boats than they were suddenly fired upon and butchered by the sepoys. The survivors, a hundred or more women and children, were slaughtered in the city some ten days later. Their bodies were thrown into a well, which has since been known as the Memorial Well, from a monument which records the atrocities.

superseded by the formal recognition, in Lord Canning’s Governor-Generalship, of the right of ruling chiefs to adopt successors, on the failure of heirs natural, according to the laws or customs of their religion, their race, or their family, so long as they are loyal to the crown and faithful to their engagements. The extent to which confidence has been restored by this edict is shown by the curious fact that since its promulgation a childless ruler very rarely adopts in his own lifetime. An heir presumptive, who knows that he is to succeed and may possibly grow impatient if his inheritance is delayed, is not desired by politic princes for various obscure reasons; so that the duty of nominating a successor is often left to the widows, who know their husband’s mind and have every reason for wishing him long life.

The Panjab and Pegu were conquests of war; the states of Satara, Jhansi, and Nagpur had fallen in by lapse. The kingdom of Oudh is the only great Indian state of which its ruler has been dispossessed upon the ground of intolerable misgovernment. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the vizir pledged himself by a treaty made with Lord Wellesley to establish such a system of administration as would be conducive to the prosperity of his subjects; and it was also agreed that the vizir would always advise with and act in conformity with the counsel of the Company’s officers. These pledges had been so entirely and continuously neglected that the whole of Oudh had fallen into constantly increasing confusion, until it subsided into

violent disorder, tumults, brigandage, and widespread oppression of the people.

In fact, the kingdom was sustained artificially under a series of incapable rulers only by the external pressure of the British dominions surrounding it, and by the presence of a subsidiary British force at the capital. The formal and even menacing warnings sent from time to time by the Governors-General to the Oudh government were as ineffectual as such intimations usually are when addressed to persons without strength or inclination to profit by them. It was impossible that the support of British troops stationed within the country could continue to be given to such a regime, while to withdraw those troops and disown all responsibility would only have let loose anarchy. And as the alternative of the temporary sequestration of the king’s authority was rejected, on deliberation, as a dangerous half-measure, the British government determined to assume the administration and to vest the territories of Oudh in the East India Company. This was done by proclamation in February, 1856; and before the end of that month Lord Dalhousie made over the Governor-Generalship to Lord Canning.

The British empire seemed now to have reached its zenith of peace, power, and prosperity, for the territory under its direct government had been very greatly enlarged, its frontier line had crossed the Indus on the north-west and the Irawadi on the southeast, and throughout all this vast dominion law and order appeared to prevail. But those peculiar symptoms of

The charge of the Highlanders before Cawnpur, under General Havelock

unrest, which Shakespeare calls the cankers of a calm world, are still in Asia (as formerly in Europe) the natural sequel of a protracted war time, when the total cessation of fighting and the general pacification of the whole country leave an insubordinate mercenary army idle and restless.

From 1838 to 1848 hostilities had been intermittent but incessantly recurring; the sepoys had been in the field against the Afghans, the Baluchis of Sind, the Maratha insurgents of Gwalior, and the Sikhs of the Panjab; and in 1852 they were engaged in the second expedition against the Burmese. Except in the calamitous retreat from Kabul in 1841–1842, where a whole division was lost, the Anglo-Indian troops had been constantly victorious; but in Asia a triumphant army, like the Janissaries or the Mamluks, almost always becomes ungovernable so soon as it becomes stationary.

The sepoys of the Bengal army imagined that all India was at their feet, while in 1856 the annexation of Oudh, which was the province that furnished that army with most of its high caste recruits, touched their pride and affected their interests. When, therefore, the greased cartridges roused their caste prejudices, they turned savagely against their English officers and broke out into murderous mutiny.

In suppressing the wild fanatic outbreak of 1857 the British were compelled to sweep away the last shadows, that had long lost substance, of names and figures once illustrious and formidable in India. The phantom of a Moghul emperor and his court vanished from Delhi; the last pretender to the honours of the Maratha Peshwa disappeared from Cawnpur; and the direct government of all Anglo-Indian territory passed from the Company to the crown in 1858. The supremacy of that government now stands uncontested, in opinion and sentiment as well as in fact, throughout the whole dominion. The extinction of the last vestige of dynastic opposition or rivalry has been the signal for the beginning of a modern phase of political life, for the complete recognition of the British dominion in India, and for the formation within the state of parties which, however they may differ in administrative views, aspirations, and aims, are agreed in the principle of loyalty to the English crown.

2. See the second chapter of the next volume.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()