The results of the decisive victory gained by Paradis at St. Thomé were soon manifested. The influence of the French became supreme in the Karnatak. Three years after that event, the governor of Pondichery was able to establish the prince whose cause he had espoused in the Subadarship of the Dakhan, a position greater than that now occupied by the Nizam. Another nobleman, likewise protected by him, he had proclaimed Nuwab of the Karnatak, with the possession of the whole of that province except Tanjur and Trichinapalli. The time had not arrived when a European power could openly assert supreme dominion, but in January 1751 almost the whole of south-eastern India recognised the moral predominance of Pondichery. The country between the Vindhayan range and the river Krishna, including the provinces known as the Northern Sirkars, was virtually ruled by the French general whose army occupied the capital of the Subahdar of the Dakhan. South of the river Krishna, the country known as the Karnatak, including Nellur, North and South Arkat, Madura, and Tinnevelli, was ruled virtually from Pondichery. The only places not subject to French influence were Madras, restored to England by the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle; Fort St. David, within a few miles of

Pondichery, held by the English; Tanjur, whose Rajah had not acknowledged the supremacy of the French nominee; and Trichinapalli, held by a rival candidate for the Nuwabship, supported by the English. Madras and Fort St. David were, under the circumstances of the peace with England, unassailable; but everything seemed to point to the conclusion that Trichinapalli and Tanya- would speedily fall under the supremacy which had successfully asserted itself over the other portions of the Karnatak. A large army, supported by a French contingent, was marching on Trichinapalli. The English, by the loss of Madras, by the failure of an attempt made in 1748 to capture Pondichery, and by the ill-success which had attended them when opposed to the French at Valkunda, had gained the unhappy reputation of being unable to fight. There seemed to be no power, no influence, capable of thwarting the plans which the brain of Dupleix had built up on the firm base of the victory gained by Paradis at St. Thomé.

Nor, had the French possessed a real soldier capable of conducting military operations – had their troops been led by a Clive, a Stringer Lawrence, or even by a Paradis – could those plans have failed of success? It happened, however, for their misfortune, that at this particular epoch their forces were commanded by men singularly wanting in the energy, in the decision, in the rapid coup d’oeil essential to form a general. At first it seemed that this misfortune would not be necessarily fatal; for if it were true that their army besieging Trichinapalli was led by men who would dare nothing, the English allies of the defenders possessed commanders of mental calibre certainly not superior. As the French were vastly superior in numbers it was clear that, the commanders on both sides being equal, the victory must in the end be with them. But they had made no provision either for time or for the unforeseen. When their plans seemed gradually verging towards success, and the fall of Trichinapalli by the slow process of famine – seemed to loom in a not very

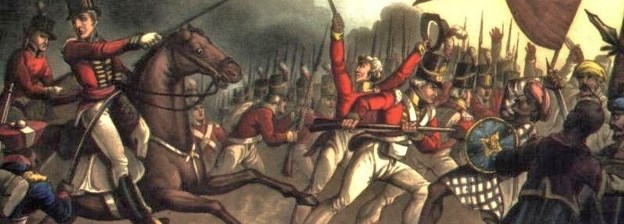

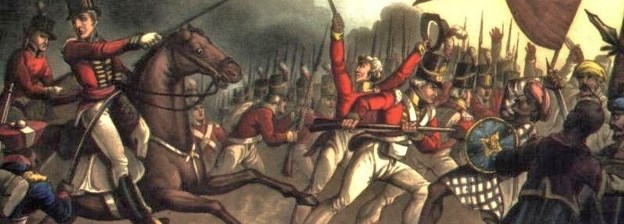

distant future, a young Englishman, not yet a soldier, though endowed by nature with the talents which go to form a finished commander, had suddenly burst into the province of Arkat, had seized the capital; then resisting for fifty days, and finally repulsing, a besieging native army, aided by Frenchmen exceeding his own European garrison in numbers, had proved conclusively to the world of Southern India – to use the actual words used by the famous Maratha leader, Murari Rao – “that the English could fight.”

The splendid diversion made by Robert Clive in northern Arkat was not in itself decisive of the fate of Trichinapalli. The French and their native allies continued to press the siege though in the same slow and perfunctory manner as before. The fate of Southern India depended upon the fall of that place. The time employed to besiege Clive in Arkat gave the French precious opportunities to take it. They threw them all away. They attempted nothing. Fancying that Clive was, at Arkat, in a trap whence he could never emerge to trouble them, they still trusted to the slow process of starvation. They were roused from their fools’ paradise by the intelligence that the young Englishman had forced the besiegers to retire; had subsequently beaten them in a pitched battle, and was then engaged at Fort St. David in raising troops to march to the relief of the besieged of Trichinapalli.

Fortune, however, had not yet abandoned the French. The blind goddess was content to give them one more chance. Whilst Clive was preparing a force to march to the relief of Trichinapalli, the energetic governor of Pondichery incited his native allies to raise a fresh army, and to send it – well supported by French soldiers – not only to reconquer north Arkat, but to threaten Madras itself. He argued, and argued soundly, that such a diversion would, in the attenuated condition of the English garrisons, render it imperative on Clive to forego his march on Trichinapalli, and hasten to the defence of the threatened posts.

These – if the French and their allies would only display energy and resolution – might be captured. The fall of Trichinapalli would not fail to follow.

At first, events fully confirmed the anticipations of Dupleix. No sooner had Riza Sahib, the Indian chief whom Clive had repulsed from Arkat and defeated at Arni, felt that the province, was relieved from the awe inspired by the presence of the young Englishman who had conquered him, than, re-uniting his scattered troops, and calling to him a body of 400 Frenchmen, he appeared suddenly at Punamalli (17 January 1752). The only English troops that could possibly oppose him were shut up, to the number of about a hundred, in Madras; about two hundred and fifty were in Arkat. The allied French and Indian forces were, therefore, practically unopposed in the field. Using their advantages – I will not say to the utmost, for, placed in their position, Clive would have employed them far more effectively – the allies ravaged the territory belonging to the East India Company down to the very sea-side; burned several villages, and plundered the country houses built by the English at the foot of St. Thomas’s Mount. The fact that peace existed between France and England probably deterred them from attempting an attack upon Madras. They worked, however, as much damage in its neighbourhood as would affect very sensibly the revenues of the country, and then marched on Kanchipuram (Conjeveram). Having repaired the damages which the English had caused to the fortified pagoda of this place only a very short time before, they placed in it a garrison of 300 native troops; then moving to Vendalur, twenty-five miles south of Madras, established there a fortified camp, from which they levied contributions on the country around. Although the forts of Punamalli and Arkat invited attack, they attempted no serious military enterprise. Their aim was so to threaten the English as to force them to send all their available troops into the province of north Arkat,

and thus to procure for the French besiegers of Trichinapalli the time necessary to capture that place. They were to run their heads against no walls, to keep their troops fresh for the emergency which was certain, when it should come, to demand all their energies, and then suddenly to strike the one blow which would secure the supremacy of the French in Southern India. It was an extremely well-devised plan, and it very nearly succeeded.

In the outset it met with the success which had been hoped for. It procured a respite for Trichinapalli. Clive, engaged at Fort St. David in making preparations for the relief of that place, was suddenly ordered to proceed to Madras, and to use there to the best advantage the means he would find at his disposal. Clive set out, reached Madras early in February, found there about 100 Europeans and a few half-drilled native levies, and expectations of the daily arrival of about the same number of Europeans from Bengal. A few days later these expectations were fulfilled. The interval had been employed in ordering up four-fifths of the Europeans and 500 of the sepoys forming the garrison of Arkat, in drilling the native levies, in raising others, in laying in stores for a campaign, and in obtaining information regarding the enemy. Clive soon learned that the allies lay still at Vendalur, apparently waiting to receive him there. On the 20th February the troops from Bengal arrived; on the 21st, Clive received information that the garrison of Arkat would march in the following morning. No time was to be lost if Trichinapalli were to be saved. On the 22nd, then, Clive set out from Madras, and, joined that day by his old soldiers from Arkat, marched at once in the direction of Vendalur. His united force consisted of 880 Europeans and 1,300 sepoys, with six field-pieces. Marching all night, he hoped to be able to surprise the enemy early the following morning. But it formed no part of the French plan to await the arrival of Clive in their camp at Vendalur. Well served by their spies, they were acquainted with all the movements of their enemy.

On the night preceding the day, then, on which Clive set out from Madras, the French and their allies, acting on a plan pre-concerted to puzzle the English leader, quitted Vendalur, and marched in different directions. Reuniting at Kanchipuram, they hurried by a forced march to Arkat, hoping to surprise its reduced garrison. With this object in view they had corrupted some of the native soldiers within the fort, and had pre-arranged with these to make a signal, to which, if all were satisfactory, their friends were to reply. They entered the town of Arkat very early in the morning, and made the signal. Receiving no response, they concluded – what was the fact – that the plot had been discovered. Then, reverting to their tactics of marching away in different directions, they quitted Arkat, only to reunite at Kaveripak and occupy there a position, in which it had been pre-determined, even should the attempt on Arkat succeed, to receive Clive. They had marched fifty-eight miles in less than thirty hours.

The French plans showed very skilful calculation. It will be clear to the reader that their object had been to alarm Clive regarding their real aims, to draw him on by forced marches towards a position where he could only fight at disadvantage. The attempt on Arkat would, they knew, incite the English leader to desperate exertions. They divined, moreover, that pressing to its relief, and marching by night, he would fall into the trap they had laid for him, for marching on Arkat he must traverse the town of Kaveripak. Before he could reach it, they would have several hours for rest and preparations. Their anticipations were realised almost to the letter.

Clive, we have seen, had set out from Madras, on the 22nd, with the object of surprising, by a forced march, the hostile forces at Vendalur. He had not proceeded quite half-way, however, when intelligence reached him of their sudden disappearance from that place and their dispersion in different directions. The second portion of the intelligence left him no option but to push on to

Vendalur with all speed to make there the necessary inquiries, He arrived there about 3 o’clock in the afternoon to find the enemy had disappeared, no one knew, or no one would say, whither. A few hours later, certain intelligence reached him that they were at Kanchipuram. That place was twenty miles distant. It was 9 o’clock; his men had that day marched twenty-five miles; but they had had a rest of five hours, had eaten, and were in good spirits. Clive, therefore, pushed on at once, and by a forced march reached Kanchipuram about 4 o’clock on the morning of the 23rd, to find that the French and their allies had been there only once again to disappear. He felt certain now that they would attempt Arkat. Without positive intelligence, however, and with troops, who, for the most part, without any previous training, had marched forty-five miles in twenty-four hours, he felt it unadvisable to move further. Contenting himself with summoning the pagoda, which surrendered on the first citation, he ordered his troops to rest. A few hours later his conjecture was confirmed by positive information that the French were in full march on Arkat. Certain that a crisis was approaching which would demand all the energies of his men Clive did not disturb their slumbers.

Arkat is twenty-seven miles from Kanchipuram. Although Clive entertained no doubt whatever that the former place would resist successfully the attempt which, he now felt sure, the French and their allies would make upon it, he was naturally anxious to reach it with as little delay as possible. Accordingly, after granting his troops a few hours’ sleep and a meal, he started a little after noon, on the road to Arkat. Towards sunset his troops had covered sixteen miles, and had come within sight of the town of Kaveripak. They were marching leisurely, in loose order, totally unsuspicious of danger, when suddenly, from the right of the road, from a point distant about 250 yards, there opened upon them a brisk artillery fire. That fire proceeded from the French guns.

That the reader may clearly understand the position, I propose to return for a moment to the French and their allies. I have already related how, in the early part of this very day, their combined forces, after having vainly attempted Arkat, had marched on Kaveripak, and taken up there a strong position, barring the road to Clive. In numbers they were superior to him, but mainly only in cavalry. Clive had no horsemen with him. His enemy had 2,500. In other respects they exceeded him only slightly, having 400 Europeans to his 380, 2,000 sepoys to his 1,300, and nine guns and three mortars to his six guns. I have searched the French records in vain to find the name of their European commander. In this respect he has been fortunate, for the conduct he displayed on this occasion was not of a character to evoke the gratitude of his nation. The commander of the natives and nominal commander of the whole force, was Riza Sahib, son of the titular Nuwab of the Karnatak.

The position they occupied had been extremely well-chosen. A thick grove of mango-trees, covered along its front on two sides by a ditch and bank, forming almost a small redoubt fortified on the faces towards which an enemy must advance, and open only on the sides held in force by the defenders, covered the ground about 250 yards to the left of the road looking eastward. In this the French had placed their battery of nine guns and a portion of their infantry. About a hundred yards to the right of the road, looking eastward, and almost parallel with it, was a dry watercourse, along the bed of which troops could march, sheltered, to a great extent, from hostile fire. In this were massed the remainder of the infantry, European and native. The ground between the watercourse and the grove and to the right of the former was left for the cavalry to display their daring. The allies were expecting Clive, and were on the alert. They had hoped that, marching unsuspiciously along the high road, he would fall into the trap they had laid, and that what with the guns on his right, the infantry on his left, the cavalry

in his front, and his own baggage train in his rear, escape for him would be impossible.

We have seen that Clive did fall into the trap. Marching unsuspiciously along the high road, the fire from the guns in the grove on his right gave him the first warning of his danger. That fire, fortunately, was delivered just a little too soon, before the infantry had reached a corresponding point in the watercourse. Still his position was full of peril. He was thoroughly surprised. Before he could bring up his own guns, many of his men had fallen, whilst the sight of the cavalry moving rapidly round the watercourse, and thus menacing his rear, showed him that the danger was not only formidable but immediate.

It was ever a characteristic of Clive that danger roused all his faculties. Never did he see more clearly, think more accurately, or act with greater decision than when the circumstances were sufficiently desperate to drive any ordinary man to despair. He was true to his characteristic on this eventful evening. Though surprised, he was in a moment the cool, calculating, thoughtful leader, acting as though men were not falling around him, and the difficulties to be met were entirely under his control. As soon as possible he placed three guns in a position to reply to the enemy’s fire. Detecting at the same time the use which might be made of the watercourse, both for him and against him, he directed the main body of his infantry to take shelter within it. Then, to check the movement of the enemy’s horsemen round the watercourse, he hurried two of his guns, supported by a platoon of Europeans and 200 sepoys, to a position on his own left of it; whilst at the same time, to clear the space around him, he directed that the baggage carts and baggage animals should march half a mile to the rear under the guard of a platoon of sepoys and two guns. Giving his orders calmly and clearly, with the air of a man confident in himself and in his fortunes, he saw them carried out with precision, before the

enemy, using badly their opportunity, had made much impression upon him.

Still the chances were all against him. He could not advance under the walls of that mango grove fortress bristling with guns. He could not retreat in the face of that cavalry. He must fight at great disadvantage on the ground he occupied. The truth of the last proposition soon made itself apparent. On his left, indeed, his men in the watercourse just held their own. They exchanged a musketry fire with the French advancing from the other end, but neither party cared or dared to have recourse to the decisive influence of the bayonet. Beyond that, the enemy’s cavalry were kept in check, for though they made many charges against the infantry and two guns on the English left of the watercourse, and even against the platoon in charge of the baggage, they made them in a manner which showed that the morale of the European gave him a strength not to be measured by numbers. In a word, they did not dare to charge home. But though he held his own in the other parts of the field, Clive was soon made to feel that on the right he was being gradually overpowered. The vastly superior fire from the guns in the grove fortress came gradually to kill or disable all his gunners and to silence his guns.

It was a situation which, Clive felt, could not be borne long. Those guns must be silenced or else –. The historian of that period, Mr. Orme, says that “prudence seemed to dictate a retreat.” If prudence so counselled, it was that bastard prudence, the bane of weak and worn-out natures, the disregard of which gained for Clive all his victories, which alone made possible the marvels of the Italian campaign of 1796, the too great regard to which made Borodino indecisive and entailed all the horrors of the Russian retreat. Such prudence, we may be sure, presented itself to the minds of many fighting under the orders of Clive, but not for one single instant to the mind of Clive himself. Without cavalry, to abandon the field in which he had

been beaten to a victorious enemy largely furnished with that arm, would be to court absolute destruction. And the destruction of Clive’s army meant the fall of Trichinapalli, the permanent predominance of French influence throughout southern India. That was the stake fought for at Kaveripak!

No, there was no alternative. It was 10 o’clock. The fight had lasted four hours and his men were losing confidence. The grove fortress must be stormed – but how? If the enemy possessed a real commander, it was impossible. The experience of Clive in warfare against the combined forces of the nations then opposed to him had, however, led him to the conclusion that confidence often produced carelessness. What if the grove fortress could be entered from the open faces in its rear? It was just possible that, in the confidence inspired by having to meet an enemy advancing only from the front, the French might have left these unguarded. It was a chance, perhaps a desperate chance, but worthy at all events of trial. Thus thinking, Clive, selecting from the men about him an intelligent sergeant, well acquainted with the native language, sent him, accompanied by a few sepoys, to reconnoitre. After an interval which, though brief, seemed never-ending, the sergeant returned with the happy intelligence that the rear approaches to the mango-grove had been left unguarded. The incident which followed showed how completely Clive was the master-spring of the machinery. He had decided – should the report of the sergeant prove satisfactory – to take 200 of his best Europeans – that is considerably more than half, for by this time nearly forty of the 380 had been killed and more had been wounded – and 400 natives, and lead them, preceded by the sergeant as guide, on the desperate enterprise. He so far carried out this scheme that he withdrew the men, to the number and of the composition mentioned, from the watercourse, and marched stealthily in the direction indicated by the sergeant. But the departure of this considerable body, and above all, the departure of the leader himself, completed the dismay

of the troops left behind in the watercourse. They suddenly ceased firing, and made every preparation for flight. Some of them even quitted the field. The sudden cessation of firing, revealed to Clive – when he had already proceeded half way on his expedition – that his presence was absolutely required on the spot he had recently quitted. He, therefore, made over the command of the detached party to the next senior officer, Lieutenant Keene, and returned to the watercourse. He arrived there in the very nick of time. His men, confused, dispirited, and disheartened, were running away. Fortunately the enemy had taken no advantage of their demoralised condition. Clive went amongst them, and succeeded, though with difficulty, in restoring order and in inducing them to renew their fire. To insure the success of the other movement, it was only necessary that they should impose on the enemy at this point. Influenced by the presence of Clive they did this, but it is doubtful whether they would, in their then state, have ventured, even under his leading, upon anything more daring. To induce them to act as they did act, it was absolutely necessary that Clive should remain with them.

Meanwhile Keene’s detachment was proceeding on its perilous enterprise. Making a large circuit, that officer reached – at about half-past 10 o’clock – a position immediately opposite the rear of the grove, and about 800 yards from it. He then halted, and calling to him one of his officers who, fortunately, understood French perfectly (Ensign Symonds), directed him to advance alone, and examine the dispositions made by the enemy. Symonds had not proceeded far when he came to a deep trench, in which a large body, consisting of native soldiers – whose services had not been required in the watercourse – were sitting down to avoid the random shots of the fight. These men challenged Symonds and prepared at first to shoot him, but deceived by his speaking French, they allowed him to pass. Symonds then made his way to the grove and boldly entered it. The sight

that met his gaze was eminently satisfactory. The guns were manned by men engaged in directing their fire against the English position on the high road. Supporting these guns and gunners were about a hundred French soldiers, whose attention was so entirely absorbed by the events in front of them that they paid no attention to their rear, which was entirely unguarded. It now became the object of Symonds not only to return, but to return by a way which should avoid the sepoys in the ditch, as much to ensure his own safety as to find a clear road for his own countrymen. Fortune came to the aid of his calm and cool self-possession. Taking a direction to the right of that occupied by the sepoys in the ditch, he rejoined his party without meeting a single person. Success was now certain. Keene at once gave the order to advance. Proceeding by the path by which Symonds had returned, he marched unperceived to within thirty yards of the enemy’s Europeans. Halting here, he poured into them a volley. The effect was decisive. Many of the Frenchmen fell dead; the remainder were so astonished, that, without even attempting to return the fire, they turned and fled, abandoning guns and position; every man anxious only to save himself. In the heedlessness of sudden despair, many of them ran into a building at the further end of the grove which had served as a caravanserai for travellers. It was running into a trap, a trap moreover in which they were so crowded that they could not use their arms. The English followed them up closely, and, seeing their defenceless condition, offered them quarter on condition of surrender. These terms were joyfully accepted, and the Frenchmen coming out one by one delivered up their arms and, to the number of sixty, constituted themselves prisoners. Many of the sepoys escaped.

The battle was now gained, for though the troops in the watercourse – ignorant of the events passing in the grove – continued their fire some time longer, the arrival of fugitives soon induced them to abandon their position and seek safety in flight. The

field being thus cleared, Clive reunited his force, and halted on the field under arms till daybreak. Surveying the horizon by the light of the early morn not an enemy was to be seen. Fifty Frenchmen and 300 of their native soldiers lay dead on the field; besides these there were many wounded. He had captured nine field-pieces and three mortars, and he had sixty prisoners. On his own side he had lost in killed, mainly from the fire of the enemy’s guns, forty Europeans and thirty sepoys. A great number of both were likewise wounded.

But the guns he had captured and the prisoners he had made constituted but an infinitesimal portion of the real advantages Clive had gained on this well-fought field. Sir John Malcolm attributes to the battle of Kaveripak the distinction “of restoring,” or “rather,” he says, “of founding the reputation of the British arms in India “; for before that “no event had occurred which could lead the natives to believe that the English, as soldiers, were equal to the French.” That was most undoubtedly its moral effect. D’Espremesnil’s sortie from Madras, and the victory of Paradis at St. Thomé had revolutionised the relative positions of the natives and the French settlers. It had given the latter a moral preponderance, foreshadowing supremacy in Southern India. In that moral preponderance the English had, at first, a very light share. They had fallen back before the greater daring and energy of their European rivals. They had done little to impress, generally, the minds of the natives. The famous Maratha leader expressed the prevailing opinion of his countrymen when he stated that prior to Clive’s heroic defence of Arkat, he had been convinced that the English could not fight. But even the favourable impression created by that brilliant feat of arms had been partly neutralised by the fact that another and a larger body of Englishmen had allowed themselves to be cooped up and besieged in Trichinapalli. Had the English lost the day at Kaveripak, there can be no doubt but that the favourable impression created by Arkat would have been replaced by

the feelings which had preceded it, and the defence of that fortress would have been universally regarded as the exception which proved the rule. The moral effect of Clive’s great victory, then, was greater even than to confirm the belief created at Arkat that the English could fight. It produced the conviction not only that they could fight, but that they could fight better than the French. It transferred to the English, in fact, the moral preponderance which D’Espremesnil and Paradis had gained for the French at Madras and St. Thome. In the history of decisive battles it becomes, then, the logical sequence of Paradis’ victory. Its material results were not less important. On the mode in which it was decided depended the possibility of the relief of Trichinapalli by the English before that place should succumb by famine or by arms to its French besiegers. On the successful defence of Trichinapalli depended whether English influence or French influence was to predominate in Southern India. Had that place fallen, French influence would have been assured for ever. That nation virtually ruled the dominions now known as those of the Nizam, including the districts called the Northern Sirloin. They only wanted Trichinapalli and Tanjur to complete their control of Southern India, the independent kingdom of Maisur alone excepted. Had Clive been defeated at Kaveripak it would have been impossible to relieve Trichinapalli. The French power would have received so great an accession of strength, moral and material, that the English would have found sufficient employment for their soldiers in the defence of their own possessions. Trichinapalli, even if it had not been attempted, would have been starved into surrender.

Materially, then, as well as morally, may the victory gained by Clive be classified amongst the decisive battles of India. It was a very decisive battle. Materially, as well as morally, it caused the transfer of preponderance in Southern India from the French to the English. It made possible the relief of Trichinapalli, and ensured the surrender of the largest French army

which had till then fought in India. That surrender gave the English a position, which, though often assailed during the thirty years that followed, they never wholly lost, and which extending year by year its roots, can now never be eradicated.

In other respects the battle of Kaveripak is well worthy of study. The French lost that battle by their neglect to guard the weak points of their position. Had they possessed a commander who knew his business, they might have won it before Clive made his forlorn attempt against that point. With their immense superiority of artillery on their left, in a secure position there, they had but to advance their centre and right, strengthened with every available man, to have forced Clive from his position. Their numerous cavalry would have completed his discomfiture. Not possessing a daring leader, they waited in their grove fortress for the slower but apparently not less certain process, for the consequences certain, under ordinary circumstances, to result from a superior artillery fire, still having the cavalry handy to complete its effect. Adopting this slower process, knowing the character of the leader opposed to them, they should have guarded with more than ordinary care the weak points of their own position. Neglecting to do this, they gave that leader a chance which ruined them in the very hour of their triumph.

On the other side, this battle revealed, more than any of his previous encounters, the remarkable characteristics of Clive as a commander. Granted that he was surprised. On this point I will simply remark that a general unprovided with cavalry, pursuing an enemy well-furnished with horsemen, compelled by circumstances outside his own immediate sphere of action to strike boldly and to strike at once, can with difficulty avoid walking into a trap such as that laid for Clive at Kaveripak. But mark his readiness, his coolness, his decision, his nerve, his clear head, and his calm courage, when he found himself compromised. Without even the shadow of hesitation he acted as

though he had no doubt as to the issue. Inspiring his men with a confidence in himself which may be termed absolute, he moved them as a player moves his pawns on a chess-board. Doubtless his death would have been followed by disaster. This became apparent when for a few moments he left the men in the watercourse to superintend the decisive movement to his right. But there is not a single great commander to whom the same remark might not apply. Deprived of its head, the body will always become inert. At Kaveripak, the disorder caused by the short absence of the leader from his accustomed place on the field, and the restoration of confidence produced by his return, proved very clearly how the spirits of the men rested on him, how without him their confidence would have vanished.

Victory is to the general who makes the fewest mistakes. Granted, as I have said, that Clive committed one great initial error by being led into a trap. That was his only error. He repaired it in a manner which deserves to be studied as an example to all commanders. But for the enemy who, having caught him, let him go! – for the want of enterprise displayed by their cavalry – for their supineness, their neglect of ordinary military precaution – for the marked absence of leadership on their side, the historian cannot find words too strong to express condemnation. They thoroughly deserved their defeat. It is a curious fact that the darkness, which in the outset seemed to favour their plans, ultimately gave opportunity for their overthrow. Clive could not have made his turning movement by daylight. So much the more worthy of condemnation is the carelessness which gave opportunities to a leader who had proved himself on other fields to be as enterprising and as daring as he was tenacious and fertile in expedients.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()