Section III

Sicily And Southern Italy

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Chapter 13: Pantelleria

IF THE Casablanca conference of January 1943 had cleared the way for full American participation in a heavy bomber offensive from the United Kingdom, it also had committed substantial air, ground, and sea forces to the conquest of Sicily (HUSKY) as an operation to be undertaken immediately after the end of German resistance in Tunisia.l The question of what would be done after HUSKY to exploit further the anticipated victory in North Africa was left for later decision.2 But with the conquest of Tunisia yet to be completed and the Sicilian invasion scheduled for early in July, it was evident through the early months of 1943 that for the larger part of the year operations in the Mediterranean would continue to impose heavy claims on AAF resources.

Soon after the Casablanca decision to mount HUSKY, General Eisenhower, in accordance with a directive from the CCS, set up Force 141 as a planning staff. For more than two months the planners wrestled with the tough problem of choosing either a widely scattered series of landings designed to seize both the important port of Palermo on the northern coast and the no less important airfields of southern and southeastern Sicily or a more concentrated set of landings intended initially for capture of the eastern airfields and the neighboring port of Catania.3 Generals Eisenhower and Alexander finally concluded that an attempt with limited resources to achieve too much in too many places involved the risk of "losing all everywhere,"4 and so on 3 May 1943 they decided to concentrate their triphibious assault on the southeastern area, whose airfields were considered to be the key to a successful invasion of the island. The CCS, meeting at the TRIDENT conference, approved the plan on 13 May.5 On that same day the last

--415--

Germans in Tunisia surrendered, and Allied headquarters moved immediately into the final preparations for HUSKY.

For the ground forces the end of the battle in Tunisia brought some respite. Air force units whose function was direct support of ground combat also found opportunity for rest, reorganization, and training. Other elements of the air forces experienced no letup but moved directly into large-scale operations preliminary to the conquest of Sicily.

The organization of the Allied air arm in the Mediterranean area had taken shape during the preceding winter* and would remain virtually unchanged until after the invasion of Italy in September. At the top of the structure stood the Mediterranean Air Command (MAC), a small policy-making and planning headquarters headed by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder. Subordinate to it were the Northwest African Air Forces (NAAF), the RAF, Middle East (RAFME) with the Ninth Air Force assigned to it, and RAF, Malta. By far the largest of these subordinate commands was NAAF, commanded by Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz and comprising the Northwest African Strategic Air Force (NASAF) under Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle, the Northwest African Tactical Air Force (NATAF) under Air Vice Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham, the Northwest African Coastal Air Force (NACAF) under Air Vice Marshal Hugh P. Lloyd, the Northwest African Air Service Command (NAASC) under Maj. Gen. Delmar H. Dunton, the Northwest African Training Command (NATC) under Brig. Gen. John K. Cannon, the Northwest African Troop Carrier Command (NATCC) under Brig. Gen. Paul L. Williams, and the Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing (NAPRW) under Col. Elliott Roosevelt. Although the Twelfth Air Force, strictly speaking, now had no legal existence,† it actually served as the administrative organization for American elements of NAAF.

NAAF had carried, and would continue to carry, the main burden of operations. Its missions, flown from bases located in or just west of recently occupied Tunisia, were closely coordinated with those of Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton's Ninth Air Force. The fighter units of the latter force (57th, 79th, and 324th Groups) had been transferred to the operational control of NATAF; similarly the 12th and 340th Bombardment Groups (M) had been attached to NATAF and the 316th Troop Carrier Group now flew its missions with NATCC. There were advantages, however, in continuing to operate the Ninth's

* See above, pp. 161-65.

† See above, p. 167.

--416--

two B-24 groups (98th and 376th)* from their bases in Cyrenaica. Not only did this permit full advantage to be taken of a well-established IX Air Service Command but it gave protection to the eastern Mediterranean with no real sacrifice of interest in Sicilian and Italian targets.6

The organization of NAAF bespoke a distinction between tactical and strategic operations which in the broader context of the war may prove misleading, however useful it may have been for the Mediterranean theater in 1943. Let it be noted, then, that the function of NAAF was almost exclusively tactical in nature; in other words, that its mission was one of cooperation in land and amphibious operations. That cooperation might be direct or indirect, it might be delivered by the relatively short-range planes of Tactical Air Force or, as in strikes against enemy transportation in Italy, by the longer-range aircraft of Strategic Air Force. But in any case, its purpose was to further the advance of our land and sea forces in accordance with plans for the occupation of specific geographical areas, and thus it differed basically from efforts to strike directly at the enemy's capacity to wage war. Except for the Ploesti and Wiener Neustadt missions of August 1943 and two attacks on Wiener Neustadt the following October, Mediterranean-based planes would not participate in purely strategic operations until after the establishment of the Fifteenth Air Force in November.

The operations of the Northwest African Strategic Air Force did, however, take on certain of the qualities of strategic bombardment. Its operations were continuous and only imperfectly punctuated by the successive phases of the ground campaign. Its objectives included an attempt to weaken the enemy in the general area of combat as well as in specific areas fixed by ground objectives. In the former it went far afield, striking at lines of communication, air bases, and other targets in an effort to reduce the enemy's strength. With reference to the more specific areas, its chief work was done well ahead of the ground attack Thus in the planned assault on Sicily, the task of Strategic Air Force was to strike the enemy in advance of the amphibious forces which would make the final assault, to soften their objective, to assist in isolating the battlefield, and in all other possible ways to contribute to the success of the invasion. And with D-day set for 10 July, there could be no pause between the victory in Tunisia and the air attack on Sicily.

* During HUSKY, three other B-24 groups would be added. See below, p. 478.

--418--

Not only were bombing operations continuous but they were directed in large part against targets long since made familiar in repeated attacks. By May 1943, Sicily itself had become an old target. Since the preceding February the island's airfields and ports had been the object of a growing attack delivered chiefly by B-17's of the Twelfth Air Force and B-24's of the Ninth, with some assistance from RAF Wellingtons, for the benefit of other Allied forces heavily engaged with the enemy in Tunisia. As part of the plan to isolate the battle area in North Africa, southern Italian and Sicilian lines of communication and Sicilian airfields had been bombed repeatedly in April.7 Sardinian fields received almost equal attention, and on 4 April, SAF raised its sights to the Italian mainland in an attack upon Capodichino airfield on the outskirts of Naples. Thereafter, the Twelfth, Ninth, and RAF, Middle East collaborated in an offensive which grew steadily in size and fury. In a campaign against enemy ports-their shipping, harbor installations, and storage facilities-Palermo had been hit eight times during April, Messina and Trapani, six times each. Against the three Sicilian ports a total of 281 heavy bomber sorties had been flown.8

During the first two weeks of May, the effort to smash the remnants of Axis forces in the Bizerte-Tunis area left little time for other operations. But immediately upon the enemy's capitulation on 13 May, NAAF took up the task of reducing the island of Pantelleria. The assault on Pantelleria, under consideration as early as the preceding February,9 had been given first place in operations preliminary to the invasion of Sicily.

Pantelleria and Lampedusa

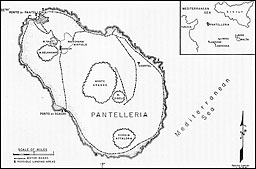

Pantelleria was certainly not an "Italian Gibraltar," as the Fascist newspapers liked to call it; even so, there was good reason to believe that its conquest might be a troublesome and expensive operation. The island, lying fifty-three air miles from Cap Bon, Tunisia, and sixty-three miles from Cape Granitola, Sicily, is an outcrop of volcanic rock, roughly elliptical in shape and with an area of some forty-two and a half square miles. Its coast line is irregular and featured by steep cliffs and a notable absence of beaches. For an invasion there was only one feasible landing area, at and adjacent to the town and harbor of Porto di Pantelleria on the northwest end of the island, but even there the harbor is small and too shallow to accommodate any but vessels of light draft, the offshore currents are tricky, and the surf is high.10

--419--

Should a landing be effected, an invading force still might expect serious trouble. The terrain is hilly, with the highest peak, Montagna Grande, reaching an elevation of 2,743 feet. The soil consists largely of lava, pumice, and volcanic ash, much of it incapable of supporting heavy vehicular traffic. The surface is cut by numerous ravines and eroded channels. Hundreds of high, thick stone walls, which divide the arable land into fields, afford protection for defending ground troops, while each of the island's houses, square and of stone or plaster, could be turned into a miniature fortress.11

Since the middle 1920's the Italian government had strengthened the natural defenses of Pantelleria. At the northern end of the island an airdrome had been constructed. The airfield itself, with its longer axis measuring about 5,000 feet, was capable of handling planes as large as four-engine bombers. On its southeast side a huge "underground" hangar, some 1,100 feet long and containing an electric light plant, water supply, and repair facilities, had been built. The field and hangar together were capable of sustaining at least eighty fighter planes. The island had been a forbidden military zone since 1926 so that detailed information about its defenses was thin, but photographic reconnaissance during the Tunisian campaign had revealed the presence of more than 100 gun emplacements. Some of them were hewn from rock; others, of concrete, were covered by lava blocks. The largest concentration was around the harbor, with the remainder so located as to command the few additional places at which landings might be attempted. A number of the guns were of sufficient size to pose a serious threat to Allied vessels of war. These defenses were supplemented by pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and strongpoints scattered among the mountains and embedded in the faces of cliffs.12

Allied intelligence estimated the size of the garrison at approximately 10,000 men--a strength which seemed more than adequate for holding the island. With its natural and man-made defenses backed by a garrison of that size, Pantelleria might prove so formidable as to require a major effort for its reduction.13 But in that garrison lay the island's chief weakness. Composed of diverse elements, none of them battle-tested or conditioned to intensive bombardment, Pantelleria's defenders were

* Lampedusa, too, had good defenses. It was well covered by pillboxes, machine-gun nests, trenches, and barbed wire; it had four mine fields, each in an area where a landing might be effected; its coast line was almost a continuous cliff some 400 feet high, broken by numerous small bays and inlets; it held more than 4,300 troops, 2 platoons of tanks, and 33 coastal and AA guns.

--421--

aware of the overwhelming power unleashed by Anglo-American forces in the closing days of the Tunisian campaign. The island was isolated from the mainland and its garrison could hope for little assistance, either in the way of air protection or in the form of reinforcements. Allied intelligence assessed the garrison's morale as doubtful, a conclusion bolstered by the poor showing of Pantellerian aircraft units against Allied air attacks near the close of the Tunisian campaign.14

However its actual strength and possible weakness might be assessed, Pantelleria and the smaller islands of the Pelagie group--Lampedusa, Lampione, and Linosa--occupied a location of great strategic importance. Pantelleria and Lampedusa, so long as they were held by the enemy, would pose a serious threat to HUSKY. Their position in the Sicilian straits enabled them strongly to influence all ship movements through the narrows. Both islands held Freya RDF stations and both had observation posts from which to detect the movement of aircraft and ships. So long as Axis observation planes worked out from Pantelleria's airfield, no invasion mounted from North African ports could hope to achieve maximum tactical surprise. That airfield, with its capacity of eighty fighters, was a constant threat against Allied bombers and ships. The island's caves and grottoes served as refueling points from which submarines and torpedo boats menaced shipping in the central Mediterranean.15

Once the islands were captured, several advantages would redound to the Allies. From Pantelleria they could operate at least one group of fighters to protect shipping and ground troops during the early stages of the invasion of Sicily--an important tactical consideration since North African airfields were out of effective single-engine fighter range and those on the British islands of Malta and Gozo could not accommodate all of the fighters required. Both Pantelleria and Lampedusa would provide sites for weather stations and bases for air-sea rescue units, while the larger island's airfield would serve as a convenient emergency landing ground for crippled planes.

The importance of the two islands, especially of Pantelleria, argued for an early assault, but it was obvious that the venture involved certain serious risks. A protracted operation requiring large commitments in men, ships, and landing craft, with the possibility of heavy losses, might weaken or even postpone HUSKY. The assault would indicate the direction of Allied intentions in the Mediterranean. A successful--or even a lengthy and courageous--defense of the islands might stiffen the

--422--

spirit of the Italian army and people just when the Allies were most anxious to break their morale.16

These and other considerations caused some difference of opinion among ground, naval, and air forces as to the wisdom of an assault on Pantelleria and the nature of that assault should it be attempted. But after the Palermo landing had been dropped in favor of a concentrated attack in southeastern Sicily, Eisenhower concluded that Pantelleria must be seized and occupied: the value of its airfield to the HUSKY landings was a clinching argument. In the absence of satisfactory beaches for an amphibious assault, he decided upon an attempt to break the resistance of the garrison, and of the civilian population, by heavy bombardment from air and sea. Even if this attack alone did not force the island to surrender, it was believed that the damage to installations, materiel, personnel, and morale ought to insure for a landing an early success, with minimum losses.17

Plans for the conquest of Pantelleria, coded Operation CORKSCREW, matured rapidly. On 9 May, Eisenhower set in motion preliminary preparations. He directed Tedder to make available for the operation the full strength of the Northwest African Air Forces, supplemented, if necessary, by heavy and medium bombers from the Middle last command. Fleet Adm. Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham, commander of naval forces in the theater, was to select a striking force of warships and other vessels for the assault and to provide naval protection for the movement of one infantry division. Together with the Northwest African Coastal Air Force, he also had responsibility for maintaining a close blockade of the island. For the landing operation, Eisenhower chose the British I Infantry Division, which had received training in amphibious warfare in England but was not slated to participate in the invasion of Sicily.18

A combined command--General Spaatz of NAAF, Maj. Gen. W. E. Clutterbuck of the British I Infantry Division, and Rear Adm. R. R. McGrigor of the Royal Navy--would command air, ground, and naval forces, respectively. With the final assault set for 11 June, these commanders had authority to postpone the landing to permit further bombardment. General Eisenhower retained responsibility for any decision, in the face of dangerous opposition and possible heavy losses, to abandon the project.19

Since CORKSCREW was to be launched from Tunisia, a portion of NAAF headquarters moved from Constantine in Algeria to Sousse,

--423--

where, with representatives of other elements participating in the enterprise, it cooperated in establishing a combined headquarters on 25 May. At the same time AFHQ created the 2690th Air Base Command, composed of air service troops under the command of Brig. Gen. Auby C. Strickland, to administer Pantelleria's affairs after its occupation and to service air units to be based there.20

For Operation CORKSCREW--the first Allied attempt to conquer enemy territory essentially by air action--the Northwest African Strategic Air Force and Tactical Air Force had at their disposal slightly more than 1,000 operational aircraft.* This figure included the two groups of medium bombers and three groups of fighters of the Ninth Air Force, which were attached to NATAF. In addition, Malta-based planes could attack enemy airdromes in Sicily and protect naval forces operating from Maltese ports, while a part of Coastal's planes could be used in the Pantellerian operation if necessary.21

Strategic Air Force was committed in whole to the operation. Of its units-four groups of USAAF B-17's, two of B-25's, three of B-26's, three of P-38's, and one of P-40's, and three wings of RAF Wellingtons and another belonging to the South African Air Force (SAAF)-all but two wings of Wellingtons participated. Tactical Air Force was only partly committed: its RAF No. 242 Group had recently been transferred to Northwest African Coastal Air Force, while Western Desert Air Force and two Spitfire wings were moving to new bases from which to participate in the coming invasion of Sicily. USAAF units scheduled for CORKSCREW were two B-25 groups; three P-40 groups plus the 99th Squadron (Separate); one group each of Spitfires, A-36's, and A-20's; and one observation squadron. There were also two RAF and two SAAF Boston squadrons, two RAF and one SAAF Baltimore squadrons, and two RAF tactical reconnaissance squadrons.22

To oppose NAAF's combat elements the German Air Force on 20 May had in the Mediterranean an estimated 989 combat planes: 541 fighters and fighter-bombers, 240 bombers, 97 close-and long-range reconnaissance, 58 ground attack, and 53 coastal. Of the total, 578 were serviceable. The Italian Air Force had 901 fighters and 484 bombers, a total of 1,385 combat planes, of which 698 were serviceable. Combined Axis air strength in the entire Mediterranean thus came to 2,374 combat planes, 1,276 of which were serviceable. But these planes.

* Units of NASAF were located in the Constantine, Souk-el-Arba, and Djedeida areas. Units of NATAF were chiefly in the Cap Bon area and southward as far as Hergla.

--424--

Pantelleria

Airborne Operations in HUSKY

were scattered from northern Italy to Pantelleria, from Sardinia to Greece, and it was estimated that the enemy had only about 900 operational combat planes on and within range of Pantelleria.23 Thus, as the air assault on the island began, the Allies had a definite but not overwhelming superiority over the Axis.

Although Pantelleria, like Sicily, had been hit more than once during the closing days of the Tunisian campaign and MAC on 14 May had ordered a "blockade by air and sea" with intermittent air attacks for "nuisance purposes,"24 the real offensive against the island began on 18 May under a plan calling for fifty medium bomber and fifty fighter-bomber sorties per day through 5 June (D minus 6).25 During this first period, operations were directed principally against Porto di Pantelleria and the Marghana airdrome in an effort to forestall the building up of reserve supplies by the enemy. These attacks (which were regular and heavy from 23 May) and a naval blockade had almost completely isolated the island by the end of the month. Photo reconnaissance reports indicated that between 29 May and 4 June only three small vessels arrived at Porto di Pantelleria and that its facilities and surrounding buildings had been severely damaged. Equally effective had been the attacks on the airdrome where barracks and administrative buildings had been destroyed, stores and dumps fired, the field itself cratered, and a large number of aircraft destroyed on the ground. After May, reconnaissance could discover no serviceable planes on the field--a fact which helped to explain the absence of enemy fighter opposition during this first stage of the assault--and when Allied forces later moved ashore they counted eighty-four enemy aircraft abandoned on the airdrome.26 Between 15 and 30 May, heavies and mediums had vigorously complemented the assault on Pantelleria by attacking airdromes in Sicily, Sardinia, and on the Toe of Italy. While these blows protected the Pantellerian operation, they also prepared the way for HUSKY.27

On 1 June, when B-17's first participated in the direct assault on Pantelleria, the emphasis shifted from the harbor and airdrome to an attempt to neutralize coastal batteries and gun emplacements--a task of special concern to the Allied command. On that day, heavies, P-38's, and P-40's dropped 141 tons of bombs; on 4 June, B-17's, B-25's, B-26's, Wellingtons, P-38's, and P-40's unloaded more than 200 tons. Bostons (A-20's) had joined the attack on 3 June. Between 18 May and 6 June, NAAF's planes, flying approximately 1,700 sorties, had battered the

--425--

port and airfield with over 900 tons of bombs and had thrown an additional 400 tons against gun positions.

Plans for the destruction of some eighty gun positions of major importance had been predicated on the assumption that if one-third of the guns in each battery could be rendered useless as a direct result of air attack, the remainder might be silenced by the effect of such secondary factors as damage to scientific instruments, disruption of communications, destruction of supplies, and demoralization of crews. The continuous bombardment would limit opportunities for repairs. Careful analysis of the island's defenses had fixed priorities for specific objectives. Daily coverage by the photographic reconnaissance wing made possible a critical examination of results as the bombing proceeded and provided indispensable assistance in the briefing of crews. This last was considered of special importance not only because the targets were extremely small but because preliminary estimates had indicated that the 1,000-pound bombs, the chief type used, would have to fall within 200 yards of the guns to effect material damage.28

As the second phase of the air attack opened on 6 June, the plan called for an around-the-clock assault that would continue with growing intensity to D-day on I 1 June. The first day saw Strategic's heavies and Tactical's A-20's, B-25's, and Baltimores, with assistance from the new A-36 (a fighter-bomber version of the P-51), lay on a heavy attack. On 7 June around 600 tons of demolitions were showered on the island, most of the bombs being directed against shore batteries. The weight of attack rose to approximately 700 tons on 8 June, on the next day to 800 tons, B-17's carrying the bulk of the load, and then on 10 June the Allied command unleashed the full force of its air power. During that day of continuous attack, bombers at times were forced to circle over the target waiting for earlier arrivals to drop their bombs. In all, nearly 1,100 planes participated in the climactic assault and dropped 1,571 tons of bombs to bring the grand total for the period extending from 1 through 10 June to 4,844 tons, a tonnage delivered in 3,647 sorties.29

Prior to 6 June the German and Italian air forces had made little effort to protect Pantelleria, but as the air assault mounted in intensity, NAAF began to meet opposition. Small groups of enemy fighters attempted interception during the 6th and the 7th; for two days there after the enemy effort dwindled and then increased as the Allied attack reached its climax on 10 June. Offensive strikes against NAAF bases

--426--

were limited to a fighter-bomber attack of 7 June on the landing grounds at Korba North and a night raid of 10/11 June by fifty planes on Sousse. These and other efforts, however, had little effect on NAAF operations. It was estimated that Axis losses during the first ten days of June totaled nearly sixty planes, a figure four times that for Allied losses over Pantelleria from 18 May to 10 June.30

On five occasions between 31 May and 5 June, the Allied air assault was supplemented by naval bombardment of Pantelleria's harbor and surrounding gun positions. The attacking forces, all of which were British, in no instance exceeded a complement of one cruiser and two destroyers. On the 8th, however, units of the Royal Navy launched a full-scale attack. Five light cruisers, eight destroyers, and three torpedo boats participated in a bombardment of Porto di Pantelleria's mole and dock and near-by batteries. The enemy's reply to the six attacks from the sea was weak and inaccurate; observers concluded that the severe air attacks of the previous week had left most of the batteries useless.31

According to plan, the island twice was offered a chance to surrender prior to D-day. On the 8th (D minus 3), immediately after the naval bombardment, three pilots of the 33d Fighter Group dropped messages demanding immediate cessation of hostilities and unconditional surrender of all military personnel. Immediately after the drop, bombers showered the island with thousands of leaflets which pointed out the futility of further resistance and the advantage in sparing the island the ordeal of continued bombings. When, after a six-hour respite, prescribed signals of surrender had not been displayed, the air assault was renewed. A second call, made on the l0th (D minus 1), likewise met with no response.32

After the failure of this second call, final preparations for the ground assault were completed and on the night of 10/11 June the British I Infantry Division embarked at Sousse and Sfax in three convoys, two fast and one slow.* The fast convoys, protected by fighters of NACAF and by surface craft, were met off Pantelleria about daybreak of the 11th by a British naval squadron from Malta. Eight miles from the harbor entrance to Porto di Pantelleria the ships lowered their assault craft preparatory to moving ashore.33

During the night of 10/11 June and up to 1000 hours on the 11th, the Allied air forces smashed at gun positions in an all-out assault. Formations

* The troops sailing from Sousse were to be employed in a ship-to-shore assault; those from Sfax, for the first time in the Mediterranean, in a shore-to-shore assault.

--427--

of medium bombers with fighter escort appeared over the island on an average of every fifteen minutes. Tactical Bomber Force (comprised of TAF's mediums) completed its bombing missions at 1000 hours, and thereafter its duties consisted largely of furnishing fighter cover over the landing areas and of standing ready to provide such other assistance for the ground forces as might be required. Control of all Tactical Air Force activities, except for a few prearranged flights, now passed to the NAAF officer in the combined headquarters aboard HMS Largs. Plans called for Strategic Air Force to renew the bombing attack at 1100 hours.

During the lull in Allied bombing operations, the landing craft started shoreward at about 1030. Up to this point the enemy had made several sporadic air attacks from Sicily, none of sufficient strength to interfere with the prelanding operations; now he made his major effort with an attack on the flotilla by a large formation of Fw-190's, which was followed by an attempted strike against the assault craft by five Me-109's. But the Focke-Wulfs failed to score a hit, and the Messerschmitts were driven off before reaching their objective by P-40's of the 57th Fighter Group.34

At 1100 hours ships of the 15th Cruiser Squadron opened fire on shore targets. A few minutes later, as the landing craft neared the end of their run, B-17's plastered the battered island with tons of bombs in a fine exhibition of flying and bombing. Between 1130 hours and 1200 hours a destroyer and several planes reported a white flag flying from "Semaphore Hill"; word was flashed to headquarters and a photo plane was dispatched immediately to secure confirmation of the report. Meanwhile, the landing operation continued. As the first assault craft reached the three beaches in the harbor area at about 1155, the naval bombardment ceased. The landings met no opposition except on one beach, where small-arms fire was quickly silenced; in the words of a British joint committee which reported on operations in the Mediterranean in 1943, "in effect active resistance on Pantelleria had ceased when the amphibious forces arrived." More troops quickly poured ashore and by 1220 hours the 3 Infantry Brigade was through the town and in possession of a sizable beachhead. The only casualty was a British infantryman who was nipped by a local jackass. Lack of opposition made it unnecessary for Strategic to lay down a scheduled expanding barrage, and for Tactical to carry out its assigned mission of close cooperation.35

--428--

While the troops were going ashore a message forwarded from Malta brought the information that Vice Adm. Gino Pavesi, military governor of Pantelleria, had asked to surrender. (On the previous night Pavesi had informed Rome that "the Allied bombing could be endured no longer"; Mussolini then had "personally ordered" the surrender of the island.*36 Further bombing missions were promptly canceled, although twelve fighter-bombers and twelve medium bombers were held in readiness for call and fighter cover was maintained over the island throughout the day. Soon after 1330 hours General Clutterbuck and his staff went ashore, and at 1735 the formal surrender of flea- and fly-ridden Pantelleria was signed in the "underground" hangar.37

Already, General Eisenhower had shifted his attention to Lampedusa whose small airfield and RDF station would be useful in providing convoy cover, and before mid-afternoon of the same day twenty-six B-26's were on their way to open an air assault on that island. Throughout the afternoon B-25's, A-20's, and A-36's of Tactical Air Force poured bombs on the port and town of Lampedusa and on near-by gun positions. During the night Wellingtons continued the offensive. Enemy reaction was confined to inadequate but fairly accurate AA fire and to attacks by long-range fighters, fourteen of which were shot down for the loss of three Allied fighters. Before midnight a British naval task force of four light cruisers and six destroyers, accompanied by an LCI carrying one company of the Coldstream Guards, reached Lampedusa from Pantelleria and opened up against installations in a bombardment supplementary to the air attack.

On the morning of the 12th unfavorable weather stopped the naval bombardment after 0630 hours but the air assault continued. Mediums and fighter-bombers swept in relays across the island.† They encountered almost no AA fire, and the few long-range enemy fighters met refused combat. By late afternoon the Allies had flown some 450 sorties, severely damaging the island's principal installations and neutralizing one-third of its batteries with around 270 tons of bombs. Four nickeling missions showered surrender leaflets on the town and airfield. The island, having failed in an effort to surrender to an RAF sergeant pilot who had landed on the airfield because of motor trouble, displayed

* According to a cable from the British, Maintenance Division to AFHQ (MC-IN6468, 15 June 1943), the Italians on Pantelleria declared that only "fear of reprisals" had prevented an earlier surrender.

† Heavies that day returned to their old targets, the Sicilian airfields.

--429--

white surrender flags around 1900 hours. Thereafter, negotiations were completed quickly, although the local commander refused to sign the surrender terms "until he was reminded that we had another 1,000 bombers at our call; then he borrowed a pen and signed."38 The Coldstream Guards went ashore to take charge of some 4,000 military and 3,000 civilian personnel, and on the morning of the 13th the island officially passed under Allied control,39 With the prompt occupation of Linosa and Lampione by British naval units the entire Pelagie group, and thus all islands in the Sicilian strait, had come under Allied control. Neither of these last two had to be bombed or shelled.40

No sooner had Pantelleria capitulated than the Allies began to prepare it for its part in the invasion of Sicily. They rounded up and evacuated from the island more than 11,000 prisoners of war. Northwest African Air Service Command, during the month-long air assault, had serviced and repaired the planes which wrecked Pantelleria and kept operational the Tunisian airfields from which the air forces operated. Now its 2690th Air Base Command, coming ashore on the heels of the ground troops, began the task of cleaning up the badly battered island. The harbor area, roads, the communication system, the airfield, and gun emplacements were restored to usefulness. By 26 June the effective work of the 2690th ABC had made it possible to establish on Pantelleria the 33d Fighter Group, which since D-day had maintained patrols over the island and protected shipping from occasional raids by enemy planes. On 17 June, General Strickland had been appointed military governor, vice General Clutterbuck.41

When HUSKY got under way on 10 July, Pantelleria had become a full-fledged Allied air base, and its fighter planes, rescue units, weather station, and emergency landing ground helped the air forces to give maximum cooperation to the ground troops as they swarmed ashore at Gela and Licata.42 Nor was the usefulness of Pantelleria--and of Lampedusa (whose airfield was serviceable by 20 June)--limited to support of the Sicilian campaign. The Allies could now place a strong defensive air umbrella over the Sicilian narrows. The sea route from Alexandria to Gibraltar could be kept open with greater security and smaller losses. Some of the pressure on Malta was relieved.43

CORKSCREW not only paid handsome dividends but because it offered unmistakable proof of the power of air bombardment to force a defended area to capitulate, it seemed destined to become a military classic. The only comparable instance was the capture of Crete by the

--430--

Germans in 1941, but at Crete the air bombardment had been followed by an airborne invasion and the troops who went in by parachute, glider, and transport plane met stiff resistance. At Pantelleria the conquest had been accomplished almost exclusively through air bombardment and surrender had come before the assault troops could contribute to the defender's collapse. The significance of this achievement even led some enthusiastic airmen to affirm that the operation offered proof that no place and no force could stand up under prolonged and concentrated air bombardment.

That contention is hardly supported by the record of CORKSCREW alone. The enemy had certainly not prepared for all-out resistance. Batteries and pillboxes were but poorly protected and scantily camouflaged. There were no shelters adjacent to the guns for crews or ammunition. Communication lines were laid above ground, and wire was used sparingly.44 Conditions on Pantelleria had been unusually favorable for the use of air power and there could be no doubt that the Allies had taken full advantage of the opportunity to give the island a severe beating.* The docks at Porto di Pantelleria were badly damaged and the town was a shambles. Roads were cut or obstructed by debris and at some points almost obliterated. The communication system was so completely knocked out that "no telephone line was intact." The electric power plant was destroyed and its lines broken in many places. The water mains were smashed, although--despite the Italian claim that lack of water had forced their surrender--there was a sufficient supply to meet all needs, provided it could be distributed. The airfield was

* From 8 May to 11 June, the Northwest African Air Forces flew 5,285 sorties against Pantelleria, dropping 6,200 tons of bombs on the island. This was done with a loss of only four aircraft destroyed, ten missing, and sixteen damaged over the island itself. The following units participated in the assault: Strategic Air Force--U.S. 2d, 97th, 99th, 30lst Bombardment Groups (B-17's); U.S. 17th, 319th, 320th Bombardment Groups (B-26's); U.S. 310th, 321st Bombardment Groups (B-25's); U.S. 1st, 14th, 82d Fighter Groups (P-38's); U.S. 325th Fighter Group (P-40's); RAF 205 Group (Wellingtons); Tactical Air Force--U.S. 12th and 340th Bombardment Groups (B-25's); U.S. 47th Bombardment Group (A-20's); U.S. 27th Fighter-Bomber Group (A-36's); U.S. 33d, 57th, 79th Fighter Groups (P-40's); U.S. 31st Group (Spits); RAF 326 Wing (Bostons); RAF 232 Wing (Baltimores); SAAF 3 Wing (Bostons and Baltimores); two RAF tac/recce squadrons. Of the USAAF units all belonged to the Twelfth Air Force except the 12th and 340th Bombardment Groups and the 57th and 79th Fighter Groups; these were units of the Ninth Air Force but were attached to NAAF. It should be noted that the 324th Fighter Group (P-40's), attached from the Ninth, flew coastal missions but had no direct part in the assault. (See AAF Historical Study No. 52, The Reduction of Pantelleria and Adjacent Islands, 8 May--14 June 1943, p. 16, chart.) USAAF units carried the bulk of the assault, flying 83 per cent of the sorties and dropping 80 per cent of the bombs. (See AAFHS-52, p. 110.)

--431--

heavily cratered.45 But the island-fortress had been badly damaged, not destroyed.

The "underground" hangar had proved to be impervious, even to direct hits, although a single attempt at skip-bombing by a P-38 had slightly damaged one of the doors. Only a few of the batteries were damaged sufficiently to prevent their being fired by determined crews. Bombing had been less accurate than expected: it had been predicted that 10 per cent of the bombs dropped would fall within a 100-yard radius of the batteries, but mediums had averaged only 6.4 per cent, heavies 3.3 per cent, and fighter-bombers 2.6 per cent. Consequently, only about one-half as many guns were destroyed as had been expected. Too, the use of delayed-action bombs against a soft surface had resulted in many craters but very little horizontal splintering so that the ratio of indirect to direct damage proved to be 4 to 1 instead of 2 to 1 as had been anticipated. Even so, indirect damage exceeded direct--gun platforms were upheaved, electrical connections severed, instruments damaged, control posts and communications destroyed, and many guns which otherwise could have been called serviceable were so covered with debris that several hours would have been needed to clear them. Most of the batteries were in no condition to oppose the landings.46

In the final analysis the morale of the defenders was the determining factor in the failure of Pantelleria to put up a strong and prolonged resistance. The air assault not only hurt the enemy's ability to resist; it broke his will. Statements by prisoners of war indicate that battery crews did not remain at their posts and that both soldiers and civilians took to cover or fled to the relatively safe hills in the central and southern parts of the island. Although fewer than 200 of the garrison had been killed and it still possessed fighting capabilities, it surrendered almost without a fight and even had initiated plans to capitulate before the Allies came ashore. It should be remembered that the batteries were subjected to a bombing intensity which averaged 1,000 tons per square mile; that the garrison was composed of men neither battle-tested nor inured to heavy and continuous bombardment; and that the island was isolated and could expect no help. The early withdrawal of all but 78 of 600 Germans indicates that long before the Allies went ashore the enemy had written off the island as lost.47

Attempts to compare the defenders of Pantelleria with those of Malta have tended to overlook significant differences--that Malta possessed air protection and that the enemy's raids had been sporadic and

--432--

marked by relatively inaccurate bombing. It could be argued--as men have--that an American, a German, or a Japanese garrison on Pantelleria would have made the landing a costly affair, but the fact remains that the Allied air forces bombed the island into submission. There were no bloody beaches at Pantelleria or Lampedusa.

Valuable lessons were learned from CORKSCREW. Improvements were needed in communications, in comprehensive briefing of aircrews, and in coordination of intelligence in the three arms of a combined force. The operation also made it plain that great care must be exercised in setting up a bomb line and that some system of canceling a prearranged bombing plan should be available to a forward headquarters. Extremely useful experience was gained in the use of a headquarters ship for the control of fighters. Still more important, Operation CORKSCREW from the beginning had been a test of the tactical possibilities of scientifically directed air bombardment of strongpoints and an exercise in the most economical but effective disposal of available air strength. The evidence showed how extremely difficult it was to obtain direct hits on an object as small as a gun emplacement even when there was little or no enemy interference. Examination of eighty guns which had been attacked from the air showed that forty-three of the eighty had been neutralized, ten of them being completely unserviceable, but that only two batteries had received direct hits. Inconclusive evidence indicated that in attacks on batteries the effective radius of the U.S. 1,000-pound bomb was only one and a half times that of the 500-pound bomb; hence, it was better to use the smaller bomb against pinpoint objectives because of the larger number of bombs which could be employed. Bombs with a delay of.025 seconds gave better results against fixed installations than bombs with instantaneous fuzes; the delayed action restricted splintering but caused greater damage from debris to delicate instruments and produced heavier ground shock. Results, indeed, showed how important it was to make a careful study of the characteristics of terrain and soil before beginning a bombardment campaign. Of significance for later air-ground operations was the evidence that strafing had only a temporary value in intimidating gun crews and should be used with other forms of attack.48 The bombing of Pantelleria with the subsequent study of results had many of the characteristics of a laboratory experiment in its influence on the analysis of target information and the development of operational techniques.

The reduction of Pantelleria provided an excellent test of the pattern

--433--

of operations which the Allies would use as they moved northward in the Mediterranean: landings would be preceded by a period of intensive air attacks by land-based planes, the attacks constantly increasing in tempo. Such a system required time and a large expenditure of bombs and gasoline; and it placed a heavy strain on aircrews, planes, and maintenance personnel. But it greatly improved the odds in favor of establishing and maintaining a beachhead, and--under a more general application--it contributed materially to later successes on the ground by isolating the battlefield so that the enemy was denied supplies, reinforcements, and freedom of movement. Thus, it saved Allied ground troops; and, in the long run, it saved combat air personnel49

Softening Up Sicily

After the fall of Pantelleria the air forces turned to tasks more immediately preliminary to the conquest of Sicily. They operated under a plan which stipulated that a primary responsibility of all NAAF units through D minus 7 should be the build-up of forces for the combined assault. Until that day, in order to avoid heavy losses and to allow for refitting, no more than steady pressure was to be maintained against the enemy.50 But even this minimum requirement demanded that every possible effort should be made to limit opposing air action threatening the build-up of Allied forces in North Africa and to disrupt lines of communication upon which the enemy's own strength depended. For the remainder of June, therefore, Allied air forces were engaged in a heavy but by no means all-out attack on enemy airfields and ports.

In this they had returned to a task taken up immediately after the fall of Tunisia. The operation against Pantelleria had demanded freedom from interference by the Axis air arm and maximum interdiction of supplies and reinforcements for the enemy. During the latter part of May the principal airfields of Sicily and Sardinia had been bombed often and hard, and when in consequence the Axis withdrew most of its bombers from their island bases to southern Italy, the Allied air forces had promptly extended their attacks to the mainland. In the last week of May they had struck heavy blows at Foggia and the two principal fields in the Naples area--Capodichino and Pomigliano. Through the first part of June they had concentrated on Pantelleria itself, with collateral missions limited to a few fighter-bomber attacks on Sicilian landing grounds, but the assignment to which NAAF now turned was new only in the sense that it had a new focus.51 Missions theretofore

--434--

had been flown with a view to the needs primarily of the Pantellerian operation. Henceforth, all efforts would be concentrated in direct preparation for HUSKY.

Chief attention went to the airfields of Sicily, where the Axis boasted nineteen principal airdromes and landing grounds and in addition a dozen newly constructed fields of lesser importance. The Sicilian airfields fell into three main groups, of which the Gerbini complex in the east was the most important. That complex became the major responsibility of the RAF and Ninth Air Force's Cyrenaica-based heavies, which gave special attention to Catania, Gerbini, Comiso, and Biscari. In a natural division of labor, NAAF directed its efforts against fields in the western part of the island. Its heavies bombed Castelvetrano and Boccadifalco, USAAF mediums struck Sciacca and Borizzo in particularly devastating attacks, and when Wellingtons joined the effort during the last week of the month, Castelvetrano received a hard blow by night. The heaviest attacks on a single day came on 30 June, when almost 200 sorties were flown against Sciacca, Boccadifalco, Borizzo, and Trapani/Milo. Since earlier bombings had forced the enemy to withdraw his bombers and reconnaissance planes from Sardinia, that island required only occasional attention. On 24 June, 36 B-24's bombed Venafiorita, and 119 mediums raided Alghero, Decimomannu, Milis, and Venafiorita on the 28th. IX Bomber Command, carrying the attack eastward to Greece, struck at Sedes airdrome (Salonika) with 49 B-24's on 24 June and at Eleusis and Kalamaki with 46 Liberators four days later. Results everywhere were good.52

It was assumed that the conquest of Pantelleria had given some indication of the Allies' next objective. Accordingly, between 18 and 30 June the planes of NAAF flew 317 heavy and 566 medium bomber sorties, with the help of 107 sorties by IX Bomber Command, for the purpose of blocking efforts to reinforce Sicily. The selected targets emphasized key supply points, terminal ports, marshalling yards along Italy's western coast, and lesser Sicilian ports of importance to coastal traffic.

Messina, terminus of the principal line of supply from the mainland to Sicily*, became the chief target. Seventy-six Fortresses struck the first blow on 18 June. Wellingtons followed with several night attacks. On 25 June, 130 B-17's of the 2d, 97th, 99th, and 301st Bombardment Groups pounded the ferry, railroad yards, docks, and warehouse areas

* Messina had a daily clearance capacity of between 4,000 and 5,000tons.

--435--

Principal NAAF Targets Prior to Invasion of Sicily, 15 June-9 July 1943

with more than 300 tons of bombs in the heaviest single attack made in June by NAAF. These missions against Messina were complemented by attacks on Reggio di Calabria and San Giovanni across the strait on the mainland, Ninth Air Force Liberators hitting each target twice. Wellingtons and B-17's also laid three attacks on Naples; Wellingtons and B-25's pounded Salerno. On 28 June, 97 Fortresses dropped 261 tons of bombs on Leghorn, severely damaging industrial and railway installations. Wellingtons and USAAF mediums renewed the attack on Sardinian targets--Albia, Golfo Aranci, and Cagliari--while forty-four P-40's carried out an unusually successful fighter sweep over the island, in the course of which they destroyed eight enemy planes, set fire to two vessels near Cagliari, and seriously damaged the railway station at La Maddalena. Between 12 June and 2 July, NAAF planes dropped a total of 2,276 tons of bombs on ports and enemy supply bases. Messina, attacked eleven times with a total of 829 tons, received by far the heaviest pounding. Albia had been attacked five times, Naples and Cagliari four times each, Palermo and Golfo Aranci three times.53 The wide distribution of targets, as in the simultaneous campaign against airfields, bespoke a purpose partly to keep the enemy in the dark as to Allied intentions.54

The enemy's air opposition during this period had been inconsistent both in quality and quantity. NAAF bombers encountered the greatest number of fighters over northeastern Sicily and southern Italy. The bombers claimed sixty-two fighters shot down against a loss of only seven planes, though as was the experience of IX Bomber Command, which claimed a total of forty-one destroyed without loss to itself, many of the American planes were damaged.

To Malta must be given some of the credit for the bombers' success. From a besieged island forced to devote its full efforts to defense, Malta had become an effective forward base for offensive air operations. On it now were based advanced headquarters of Desert Air Force, all of that organization's fighter squadrons, and many other of its units. Malta-based fighters, assisted by Spits from the near-by island of Gozo, furnished cover and escort for NAAF and Ninth Air Force bombers within a 100-mile radius of the two islands, supplied diversions for the bomber attacks, carried out their own offensive sweeps, and through missions undertaken by Spitfire fighter-bombers added weight to the attack on enemy airfields in southern Sicily.55 And even more important, Malta stood ready, as did Pantelleria to the west, to offer powerful

--437--

assistance in guaranteeing control of the air over the waters through which soon would pass the amphibious forces of the Allied assault on Sicily.

The final phase of pre-HUSKY air operations began on 2 July (D minus 8) when the Allied air forces launched a systematic attack of growing intensity against enemy airfields for the purpose of eliminating effective air opposition to the invasion. Reconnaissance indicated that the enemy had largely withdrawn his fighters from the western fields of Sicily and from the bases around Palermo in the north for concentration chiefly in the Gerbini complex. He earlier had pulled back his bomber force to the mainland fields of Italy, and so the task in the final week preceding the invasion was mainly that of concentrating Allied efforts against the fields of eastern Sicily and of attempting to force a further retreat of the bombers northward in Italy. It would be necessary also to render unusable advanced fields in Sardinia from which long-range bombers might attack the HUSKY force and similarly to discourage the use of more northerly situated bases in Italy. From D minus 8 to D-day, in short, the primary mission of Allied air forces was to knock out the enemy's aviation.

Abandoning the earlier division of responsibility between NASAF and IX Bomber Command, the heavies of both organizations concentrated their blows on Gerbini and its satellites. The mediums of NATAF took over responsibility for the fields of western Sicily, and geographical considerations tended to give the Ninth Air Force the major part of the job over southern Italy. In planning the final knockout, it was fully understood that attacks would have to be well timed and often repeated, for experience had shown that spasmodic raids, causing only temporary damage, seldom produced decisive results. Areas containing a number of fields were divided into sectors for specific assignment to definite formations of planes. On some occasions heavy attacks would be laid on all but one or two fields in a given area, and then when the enemy diverted his fighters to the unscathed fields the Allies followed with a concentrated blow on them. Increasing attempts by the GAF to achieve maximum dispersion by use of satellite "strips" were countered by mass strafing and fighter-bomber attacks, a method which proved particularly effective against the Foggia and Gerbini complexes. A follow-up with fragmentation bombs added measurably to the effectiveness. Enemy fighters on patrol frequently

--438--

returned home to find that there was no runway on which they could land.56

The weight of the attack was delivered by the heavy bombers in missions both near and far. Employing usually formations of twenty-four planes in six-plane flights, the heavies went out from their fields in Africa again and again with each flight carefully briefed on a specific target. Experience showed that an attack about noon took advantage of the position of the sun and was more likely to achieve the desired surprise. The type of bomb carried depended on the target. For hangars and installations the U.S. 500-pound GP was considered the best, while for dispersal areas the 100-pound demolition and the 20-pound fragmentation bomb in 120-pound clusters got the best results.57 At the beginning of the week-long attack, the bombers carried fragmentation clusters in large numbers for the purpose of destroying aircraft on the ground. As D-day approached, they substituted demolition bombs in an effort to put installations out of commission.

Ninth Air Force opened the campaign on 2 July with ninety-one B-24's sent against the airdromes at Grottaglie, San Pancrazio, and Leece, all in the Heel of southern Italy. On the following day NASAF hit the advance landing grounds of Sardinia. Then for three days NASAF and the Ninth combined their forces in a smashing assault on the fields of eastern Sicily, while the mediums of NATAF pounded the airfields lying in the western and central parts of the island. Gerbini and its satellites received a thorough battering, the outstanding blow being delivered by B-17's on 5 July with an estimated destruction of 100 enemy planes. While Wellingtons operated by night against Sardinian airdromes, the attack on Sicilian fields continued through the final three days before D-day. Between 3 and 9 July, NAAF aircraft dropped 1,323 tons of bombs on the Gerbini complex alone, and to this weight planes of the Ninth Air Force added 197 tons.

As a result, Gerbini and seven of its twelve satellites had been rendered unserviceable by D-day. Other key fields fared not much better: Castelvetrano was abandoned, Comiso and Boccadifalco could not be used, lesser Sicilian fields and those in Sardinia had been largely neutralized. In Sicily, only Sciacca and Trapani/Milo were fully operational. Photo reconnaissance indicated that approximately half of the enemy's Sicily-based planes had been driven from the island to the mainland, and by the close of the HUSKY operation Allied personnel had counted approximately 1,000 enemy aircraft abandoned or destroyed

--439--

in Sicily. The persistent bombing of the week preceding the invasion also had forced the enemy to come up and fight with results that are indicated by Allied claims of 139 planes shot down in combat. Conclusive proof of the work done came on D-day, for on that day the Allied air forces dominated the air over Sicily. Indeed, the enemy's air arm interfered so little with the subsequent land campaign that it soon became possible to reduce the scale of Allied missions against airfields to 20 per cent of the total bomber effort. After the assault phase of HUSKY, our bombers had thus been largely released from purely counter-air force operations.58

With the greater part of the air effort from D minus 7 to D-day directed against the enemy's air arm, attacks on other types of targets were confined very largely to raids by night bombers and fighterbombers. Welling tons attacked the ports of Cagliari and Olbia in Sardinia and Palermo and Trapani in Sicily, while A-36's of the 27th Fighter-Bomber Group bombed and strafed supply centers in southern and central Sicily. Liberators of the Ninth, in executing the relatively few attacks made by heavies on ports and other LOC targets, hit Messina, Catania, and Taormina hard, the attack on the latter being directed in part against an enemy headquarters. Other activities of NAAF's combat planes included strafing raids, offensive sweeps, convoy protection, and a not too successful attempt to put German radar stations out of action by bombing and strafing.59

Enemy opposition to Allied air operations during the intensive preinvasion period was spotty. Some attacks met strong and persistent opposition, while others met almost none. For example, B-17's over Gerbini on 5 July were intercepted by more than 100 aggressive fighters; but a short while afterwards a second force of B-17's and B-25's saw no enemy planes. Apparently, the enemy was so short of crews and planes that he had to pick his spots. Offensively, the Axis air forces carried out only one raid, although reconnaissance was maintained on a normal scale. Allied scores indicated that throughout the pre-HUSKY operations the enemy had lost in combat a total of 250 planes against Anglo-American losses of 70 aircraft.60

The experience of the Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing through the period extending from 15 May to 10 July had more than justified the prediction of the air plan for HUSKY that the tasks of NAPRW would be "continuous and exacting." The wing flew in all over 500 missions in preparation for the invasion. Not more

--440--

than one in ten was accomplished without interception, and in addition flak was usually encountered. Nevertheless, NAPRW mapped the entire 10,000 square miles of Sicily, and made available many special photographs and reports required for planning purposes. Naval forces required photographs of virtually every port in the western and central Mediterranean, a demand met by covering daily the more important ports from Gibraltar to a line Corfu-Tripoli--by photographing twice a day those ports in which units of the Italian fleet were located--and by visiting at least once a week the smaller ports used only by coastal craft. The air forces demanded coverage of all airdromes in an area which included Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Italy, and the western Balkans. Once a week the reconnaissance squadrons photographed within the limits of a four-hour period all airfields in order to get an exact reading on the location of enemy planes at a given time. In addition, NAPRW provided special coverage of harbors, industrial areas, and lines of communication to meet the need for target data for the heavy bombers.61

Coastal Air Force, predominantly British in composition, had carried an equally varied responsibility. It escorted convoys through the Mediterranean, and so thorough was its cover that enemy planes made few attempts to attack Allied shipping. The major enemy effort came on 26 June when over 100 Ju-88's, FW 109s, and Cant.Z-1007s attacked an eastbound convoy off Cap Bon. Coastal's fighters destroyed six of the enemy's planes and so interfered with his operations that no vessel suffered serious damage. During the nine days preceding 10 July, NACAF's aircraft flew 1,426 sorties on convoy escort duty alone. They protected Allied harbors, against which the enemy directed most of his offensive effort during June and July. With every port from Oran to the border of Tripoli laden with shipping for HUSKY, the enemy attempted to strike at these lucrative targets in a series of night attacks, but Coastal's fighters handled the raids so effectively that not a single ship was sunk and only one was damaged. NACAF also collaborated with naval forces in the protection of shipping against submarines. Losses to the enemy were extraordinarily low, only nine ships being sunk between 1 April and 10 July.

Nor were Coastal's operations confined to defensive measures. Around the middle of June it was given a bomber unit, consisting of three day-torpedo Beaufighter squadrons, one night-torpedo Wellington squadron, a U.S. B-26 squadron, and a flight of reconnaissance planes. Placed under RAF 328 Wing, the force received orders to

--441--

watch the Italian fleet, harass shipping, and interfere with the efforts of the enemy to reinforce his insular holdings in the central Mediterranean. The unit promptly went into action, and between 18 june and 10 July sank or damaged a dozen ships ranging from armed trawlers to a 4,000-ton merchant vessel. As a final duty, Coastal flew an average of eight air-sea rescue sorties per day during the preparatory phase.62

By the end of D minus 1 (9 July), then, the Allied air forces had cleared the way for the invasion of Sicily. The enemy's air arm had been driven from the island or largely pinned down on battered fields, and his lines of supply and reinforcement had been so hammered that the normal flow of materiel and personnel was seriously retarded. With superiority in the air established, NAAF and the Ninth Air Force stood ready to assume the additional duties the actual invasion would impose upon them.

The HUSKY Plan

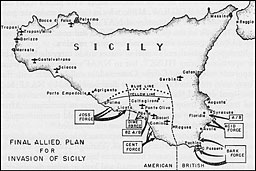

The final outline plan for the invasion of Sicily which had been approved by the CCS on 13 May 1943 involved a reallotment of objectives between the Eastern (British) and Western (U.S.) task forces and completely changed the original logistical plan which had been based on the early utilization of the port facilities at Palermo. It did not, however, affect the broad plans for the allocation of resources to the two task forces nor alter the original basic scheme for combined land, sea, and air operations, except that the objectives of several airborne missions, which in the earlier plans had been beach defenses, were changed to strategic inland points whose capture would facilitate the advance of the ground forces.

Specifically, the plan called for eight simultaneous seaborne assaults to be made along approximately 100 miles of coast line extending from Cap Murro di Porco (just below Syracuse) around the southeastern tip of the island and westward as far as Licata.* The British Eighth Army under command of Gen. Sir Bernard L. Montgomery was to land on the eastern coast. Its ACID Force would go ashore between, and drive toward, Syracuse and Avola; BARK Force would invade at three points around the southeasternmost tip of the island, with Pachino and its airfield the immediate objective. The American troops were divided into three assault forces: DIME, CENT, and JOSS. The DIME-

* The area of Sicily is around 10,000square miles. Its terrain is characterized chiefly by mountains which rise to their greatest height in the northeast. The coastal strip is narrow and the only plain of any size is to the west and south of Catania.

--442--

CENT assault, under command of Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley of II Corps, was to land in the Gela-Sampieri area; capture the airfields at Ponte Olivo by daylight of D plus I, the field north of Comiso by daylight, and the field north of Biscari by dark of D plus 2, in order to extend its beachhead inland to "Yellow Line"; and make contact with the British near Ragusa. The JOSS assault, under Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., was to land in the Licata area, capture the port and airfield on D-day, protect the left flank of the invasion forces against interference from the northwest, and on the right flank gain contact with II Corps.63

Final Allied Plan for Invasion of Sicily

NAAF carried the lion's share of the responsibility for supporting air operations.64 It was to provide close cooperation for the assault forces and to launch the paratroop attacks. Assisted by units of Middle East and Malta it was to destroy or neutralize enemy air forces within range of the invasion area, protect naval operations and the assault convoys, attack enemy shipping and naval forces, and defend Northwest Africa and captured areas in Sicily against air attack. With other air forces in the Mediterranean, and those in the United Kingdom, it would share in the execution of plans for cover and diversion. It was expected that after D plus 3, NAAF's many and varied duties would be

--443--

made easier by the capture of enemy airfields in southern and southeastern Sicily from which up to thirty-three and a half squadrons of Allied planes could operate.65

In order to exploit to the fullest the inherent flexibility of air power, as well as to assure a high degree of coordination between Strategic and Tactical during and after the invasion, the air plan provided that units of either air force might be placed under the operational control of the other for specific operations whenever the situation required it. Further, in order to coordinate tactical operations over the Eastern and Western task forces, all units based on Malta were placed under the command of the AOC RAF, Malta, who in turn was under the general direction of the commander of NATAF. This arrangement permitted the bulk of the air force to be shifted and concentrated as required by the ground situation and enemy air reaction.

Strategic, Tactical, and Coastal air forces would carry the burden of air operations during HUSKY, but to NAAF's other elements went important roles. Troop Carrier Command, in collaboration with the Army units concerned and subject to directions issued by NAAF, had developed detailed plans for the paratroop and glider operations and had trained the troop carrier units which were to participate. After the initial paratroop operations, the command would transport equipment and supplies to Sicily and evacuate the wounded.66

Few if any activities outranked in importance the diversified obligations carried by Air Service Command. Through preceding weeks it had distributed the equipment necessary to bring NAAF combat units up to full strength, it had constructed and kept in repair the airfields from which the planes operated, it had kept the planes in repair and provided for them standard maintenance, for troop carrier units it had assembled hundreds of gliders for use in the paratroop drops, it had provided and trained service units for movement to Sicily with the air task force which was to follow the infantry ashore, and withal it had been responsible for the accumulation and disposition of the vast quantities of expendable stores and spares required by an air force heavily committed against the enemy. After D-day it had the task of insuring the delivery of all necessary supplies and stores to air units moving forward to fields in Sicily. It would establish in Sicily as soon as possible the normal supply and maintenance service for the USAAF units.

Elements of the service command would go ashore on the heels of the first assault troops, and, as soon as the beachheads had been made

--444--

secure, additional units would be landed. During and after D-day the command would provide "housekeeping" and the many other prosaic but indispensable services which were its routine duties. Routine as they may have been, combat operations were fully dependent upon them.

Normal channels of supply for the air task force could not be employed during the assault phase of HUSKY, so special arrangements--outlined in an air administrative plan--had been made for the provision of such expendable items as gasoline, bombs, small-arms ammunition, and oxygen. Basically, the plan was to ship a few stocks with the initial air force ground parties and to build up thereafter by means of later shipments. To keep losses at a minimum the stocks sent with the assault convoys would be small and distributed among several ships. Thus, the loss of one or two ships would not immobilize air operations from the island, but the plan had the disadvantage of scattering supplies along miles of beaches.67

It should be noted that the air plan dealt for the most part with broad policies and that it had not been integrated in detail with ground and naval plans. This was deliberate, and the result of sound strategic and tactical considerations emphasized by experience in the Tunisian and Western Desert campaigns. There would be no parceling out of air strength to individual landings or sectors. Instead, it would be kept united under an over-all command in order to assure in its employment the greatest possible flexibility. It would be thrown in full force where it was needed, and not kept immobilized where it was not needed. Too, the chief immediate task of the air arm was to neutralize the enemy air force, a fluid target not easily pinpointed in advance.68

As the invasion convoys steamed toward Sicily on the night of 9/10 July, the Allied air forces numbered approximately 4,900 operational aircraft of all types, combat and noncombat, divided among 146 American and 113.5 British squadrons.*69 The German and Italian air forces opposing them were estimated to have between 1,500 and 1,600 aircraft based in Sicily, Sardinia, Italy, and southern France. The advantage indicated by these figures was better than 3 to 1, but the advantage in combat aircraft was nearer 2 to 1. It was not too great a margin for the tasks that lay ahead.

* American units made up most of the bomber and air transport force and about onethird of the fighter contingent; the RAF provided a majority of the single-and twinengine fighters and coastal aircraft and the entire night bomber force.

--445--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (12) *

Next Chapter (14)

Notes to Chapter 13:

1. For pre-Casablanca efforts to set up post-TORCH operations, see WP-III-5, Italy, in Office Services Br., AFAEP; Intel. Service, AAF, Air Offensive Against Italy, 18 Nov. 1942; JCS 154, 18 Nov. 1942; CCS 124, 19 Nov. 1942; CPS 49/1,27 Nov. 1942; CPS, 39th and 40th Mtgs., 30 Nov. and 3 Dec. 1942; CPS 49/2, 4 Dec. 1942; CPS 49/3, 8 Dec. 1942; CCS 124/1,30 Dec. 1942; CCS, 54th Mtg., 31 Dec. 1942. For the decisions made at the Casablanca conference see Gen. D. D. Eisenhower, Report on the Sicilian Operations (cited hereinafter as Eisenhower Rpt.), and CCS 170/2, 23 Jan. 1943. The decisions were not made without argument between the Americans and the British and involved a certain amount of give and take. (See, for example, Eisenhower Rpt.; CPS, 55th-68th Mtgs., 14-22 Jan. 1943, passim; JCS, 50th-58th Mtgs., 13-22 Jan. 1943, passim; Sp. Mtgs. Between the President and the JCS, 15, 16 Jan. 1943; Casablanca Conference, ANFA Mtgs., Jan. 1943.)

2. For discussions at Casablanca on post-HUSKY operations, see CPS, 55th, 58th, 66th Mtgs., 14, 16, 22 Jan. 1943; JCS, 50th, 51st, 52d, 54th, 57th, 58th Mtgs., 13, 14, 16, 18, 21,22 Jan. 1943; 1st and 2d Sp. Mtgs. Between the President and the JCS, 15 and 16 Jan. 1943; Casablanca Conference, ANFA Mtgs., Jan. 1943; CCS 165/2 and 170/2, 22 and 23 Jan. 1943.

3. Eisenhower Rpt. Force 141 was composed of officers from the American and British armies, navies, and air forces.

4. Eisenhower Rpt.; Francis de Guingand, Operation Victory (London, 1947), p. 274; msg., Algiers to WAR for CCS, 7892 (NAF 182), 20 Mar. 1943; CM-IN-6513, Algiers to WAR for CCS from Eisenhower, NAF 207, 11 Apr. 1943.

5. Eisenhower Rpt.; CM-IN-2316, Algiers to WAR, 4 May 1943.

6. See CM-IN-11505, Algiers to WAR, 18 May 1943.

7. For details of these early operations beyond the littoral of North Africa, see Eisenhower to C's-in-C ME, AIR 16, 24 Nov. 1943; AIR 91,98, and 100-102, 9, 15, and 18-20 Feb. 1943; CM-IN-2240, Cairo to AGWAR, AMSME 1980, 5 Dec. 1942; histories, 98th and 376th Bomb. Gps.; RAF Middle East Review No. 2, Jan.-Mar. 1943; AAFRH-5, Air Phase of the North African Invasion; AAFRH-14, The Twelfth Air Force in the North African Winter Campaign.

8. Hq. NAAF Operations Bulletins 1 and 2; RAFME Review No. 3, Apr.-June 1943.

9. TWX, ETOUSA to Eisenhower, 20 Feb. 1943, which specifically suggested that consideration should be given to the possibility of capturing Pantelleria because of its value as a fighter base in the invasion of Sicily. See also cable, Eisenhower to Marshall, 17 Feb. 1943, which noted that AFHQ was studying the possibility of an assault on Pantelleria.

10. Pantelleria Island Landing Beaches, prepared by the Beach Erosion Board, Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army, April 1943; Journal of Geology, XXI, 1913,654; Terrain Intelligence, Pantelleria Island, prepared by the U.S. Geological Survey, Feb. 1943 (Special Repon, Strategic Engineering Study No. 56). In the preparation of this section the writer found most useful AAF Historical Study No. 52, The Reduction of Pantelleria and Adjacent Islands, a monograph prepared by Dr. Edith C. Rodgers of the Air Historical Group. Useful, too, were the writer's own observations while on Pantelleria, September 1944.

11. See n. 10, above.

12. Pantelleria Operations, a dispatch by Gen. D. D. Eisenhower, June 1943 (cited hereinafter as Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.); Strategic Engineering Study 56; The Times (London), 12 June 1943; New York Times, 13 June 1943; G-2, AFHQ, Intelligence Notes-Pantelleria and Lampedusa, 20 July 1943 (cited hereinafter as AFHQ, Intel. Notes, 20 July); observations of the writer.

13. Hq. NAAF, Report of Air Participation in the Pantelleria Operation, 7 Aug. 1943, App. I: Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.; New York Times, 6 June 1943.

14. Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.

15. Ibid.; Hq. Force 141, Operation HUSKY, 9 May 1943, in files of British Air Ministry, Air Historical Branch (cited hereinafter as BAM [AHB]). Attention is invited to an Anglo-American agreement which permits information from certain classified documents of one nation to be incorporated into the text of publications of the other nation but which forbids citation of the specific document in footnotes. Because of this agreement, the writer has been unable to cite specifically certain documents which he was permitted to examine in the files of the British Air Ministry, Air Historical Branch, and from which cenain material appearing in the text was obtained.

16. Hq. Force 141, Outline Signal Plan for the Occupation of Pantelleria and Lampedusa, and Appreciation of the Signal Problems Involved in the Seizure and Occupation of Pantelleria and Lampedusa, in BAM (AHB); RAF Mediterranean Review No. 6, pp. 57-59.

17. Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.; testimony of Gen. Eisenhower before the Committee on Armed Forces of the U.S. Senate, 25 Mar. 1947; CM-IN-7151,Algiers to War, 11 May 1943; memo for CG NAAF from Brig. Gen. H. R. Craig, 14 May 1943, msg., Freedom sgd. Eisenhower to ME, 11 May 1943, and Hq. Force 141, Operation HUSKY, 9 May 1943, last three in BAM (AHB).

18. NATAF, Participation in the Capture of Pantelleria and Lampedusa, p. 95; Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.; memo for CG NAAF from Craig, 14 May 1943, in BAM (ABB).

19. See n. 18, above.

20. Hq. AAFSC/MTO, Air Service Command on the Island of Pantelleria.

21. History, 12th AF, Volume III, The Twelfth Air Force in the Sicilian Campaign; NATAF, Participation in the Capture of Pantelleria; draft history, 12th AF, Pt. I, chap. xii; Opnl. Analysis Sec., Hq. NAAF, Pantelleria, 30 May through 11 June, in History, 12th AF, Volume III, Annex 3.

22. See n. 21,above.

23. Figures on strength of the German and Italian air forces supplied by the British Air Ministry, Air Historical Branch, through the counesy of Mr. J. C. Nerney and S/Ldr. L. A. Jackets.

24. CM-IN-5757 and 6087, Algiers to AGWAR, 9 May 1943; CM-IN-5895, Spaatz to Arnold thru Algiers to AGWAR, 9 May 1943; CM-IN-1214, 6844, 6856, Algiers to AGWAR, 2, 10, 11 May 1943; 12th AF Intel. Sums., May and June 1943; RAFME Review No.3, pp. 41,42. The first heavy bombing of the island was on 8 May when P-38's hit Marghana airfield with 1,000-pound bombs, (See Mediterranean Air Command, Operational Record Book [cited hereinafter as MAC, ORB], App. 52, in BAM [AHB]. For the order to blockade Pantelleria, see msg., MAC to NAAF [Adv.], A833, 14 May 1943, in BAM [AHB].)

25. Eisenhower, Pantelleria rpt.; NAT AF Opn. Instruction 98, in Participation in the Capture of Pantelleria, Annex A; Hq. XII Air Support Comd., Pantellerian Campaign (14 May-12 June 1943); RAFME Review No. 3. In the first attack of the period, on 18 May, B-25's and B-26's dropped 97 tons on Porto di Pantelleria. (See MAC, ORB, App. 52.)