Section V

Final Reorganization

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Chapter 22: Final Reorganization

WHILE planning an all-out air attack on Germany as the prelude to OVERLORD, AAF and RAF leaders struggled with complex questions of command. The issues which developed, although not always openly acknowledged, stemmed partly from considerations of national policy and prestige and were bound up with the over-all problem of the control of Anglo-American forces then being assembled for the invasion of western Europe.

During 1942 and the early part of 1943, British counsel on strategy in the war against the European Axis had tended to prevail at meetings of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Britain's experience and greater state of preparedness, the result of having been at war for more than two years longer than the United States, lent weight to British opinion. In general, the American position on strategy had been less concerned with ultimate political and economic aims than was the British view. The Joint Chiefs of Staff had consistently favored an invasion of western Europe as the quickest and surest means of relieving pressure on the U.S. S. R. and bringing the war to a decisive conclusion. To this proposal the British had seemed at best lukewarm, and they showed a preference for exploiting the initial Allied victories in the Mediterranean, a fact American leaders were inclined to attribute to Churchill's influence in the interest of British political policy in Europe.1 It would be difficult to prove that Anglo-American strategy in the European war should have been otherwise than it was, for an invasion of western Europe in 1942 or 1943 would have been far more of a gamble than it proved to be in 1944. But the differences in strategic outlook naturally colored the views of both nations on the subject of the command of the combined forces for OVERLORD.

With reference to such earlier plans for the invasion of western

--733--

Europe as SLEDGEHAMMER, ROUNDUP, and the plan ordered at Casablanca to be prepared for the eventuality of an unexpected collapse of Germany, it had been assumed that a British officer would command the invading Allied forces, since the British would have to contribute the major part of the forces. By the summer of 1943, however, American production and manpower were coming into full play, not only to lend weight to the strategic views of the Joint Chiefs but to argue for the selection of an American as the supreme commander. When Roosevelt and Churchill met with the Combined Chiefs in the QUADRANT conference at Quebec in August it was obvious that the bulk of the ground and air forces to be committed to OVERLORD would be American. Accordingly, Churchill agreed that the supreme command should go to an American, with combined air and naval commanders responsible to him. The question of a separate combined command of ground forces under the supreme commander was left in abeyance.2

The decision at Quebec represented a major concession by the British. Long accustomed to the dominant role in the world, with interests in Europe outmeasuring those of the United States, and with some reason to feel that a greater experience in European affairs lent special qualifications to her leaders, Britain could have been pardoned a feeling that the supreme command belonged to her. For the nation which had stood so long in the front line, which had experienced the black days of Dunkirk, and which would now provide the springboard for the invasion, it must have been difficult to accept any but the leading role in the liberation of Europe. And having yielded on the supreme command, the British enjoyed a natural advantage in the choice of subordinate commanders.

This was particularly true in the case of the air command, for the RAF held advantages of its own. It had been an independent air force since 1918, and thus for a quarter of a century had occupied a position in its nation's defense superior to any yet achieved by the AAF. The Battle of Britain had raised its prestige to a high level and, after an uncertain beginning, the strategic bombardment of Germany by the RAF Bomber Command had captured the imagination and hope of the Allied world. Only with difficulty had the AAF fought off repeated suggestions, coming as frequently from American as from British sources, that it surrender its own tactical principles to join with RAF Bomber Command in an expanded campaign of night bombardment. Since January

--734--

1943, Sir Charles Portal had served as the representative of the Combined Chiefs of Staff for the over-all direction of CBO operations. The very nature of air operations imposed upon the Americans a special dependence on British bases, and that dependence would be affected to a lesser degree than with other arms by the movement of the assault forces onto the continent.

But if the AAF had been theretofore the junior partner in the air war against Germany, it promised soon to outgrow its colleague. It was clear by the summer of 1943 that the AAF would play an equal or even a dominant role in the scheduled invasion of Europe. Moreover, the AAF was young, aggressive, and conscious of its growing power. It was guided by the sense of a special mission to perform. It had to justify the expenditure of billions of dollars and the use of almost a third of the Army's manpower. It had called off for the duration of the war earlier campaigns for an independent status, but it knew full well that its position in the postwar organization of national defense would depend upon the record now to be established. It sought for itself, therefore, both as free a hand as possible to prosecute the air war in accordance with its own ideas and the maximum credit for its achievements. Under these circumstances it was too much to expect that all questions could be resolved to the complete satisfaction of either the AAF or the RAF.

Allied Expeditionary Air Force

A small Anglo-American air staff had been established at Norfolk House under Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory in June for collaboration with General Morgan as COSSAC in the drafting of plans for OVERLORD. Leigh-Mallory had commanded a fighter group during the Battle of Britain, and late in 1942 he had been elevated to the command of RAF Fighter Command. Upon receiving the additional assignment to the Norfolk House planning group in June, he had moved promptly to convert a large part of RAF Fighter Command, which heretofore had operated as a static organization for the air defense of Britain, into a tactical air force possessed of the requisite mobility for support of the scheduled expedition into Europe. And when at Quebec, in August, Sir Charles Portal urged the immediate designation of an air commander for the invasion, Leigh-Mallory received the assignment.3

Events soon proved, however, that it had been easier to agree on the designation of the tactical air commander than it was to reach an understanding

--735--

on the extent of his authority. The headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force would not be activated until mid-November and still another month would elapse before it enjoyed any control whatsoever over the Ninth Air Force, which was established in England in October as the American component of the expeditionary air force. The AAF adhered to the policy of reserving to itself as much control as possible over its air units by granting to the projected AEAF only operational control of the American tactical air force. As Eaker put it in September, as far as the Americans were concerned, Leigh Mallory would command "only the Ninth Air Force Commander, and not our soldiers and individual units contained therein."4 Portal, presenting the British view, felt that "it would be a great mistake to divorce administration from the other functions of Command. . . . One of Air Marshal Leigh-Mallory's responsibilities will be to make administrative plans and preparations for the move across the channel and I do not believe that this will be possible if he is not to assume full administrative control until his forces are established on the Continent."5 But some Americans felt that there was a desire on the part of the British to exercise undue control of American air units, presumably in the interest of British prestige, and this they were not disposed to permit.6

By early September both Arnold and Portal had drawn up draft directives for the air commander which further clarified the conflicting national views. Subsequent interpretations by others, especially those by Eaker, Devers, and Leigh-Mallory, followed the lines laid down in these two drafts. Different usages of terminology occasioned some difficulty. The RAF term "administration" included what the Americans called "logistics," and this broader usage caused some additional apprehension.7

Arnold, Eaker, and Devers agreed that the directive to Leigh-Mallory should limit his powers to "tactical coordination and control." They opposed administrative control of the Ninth Air Force by a combined headquarters, arguing that the administrative channels of the armed forces of the two nations had theretofore remained separate and that substantial differences between the two administrative systems made it undesirable for officers of either the RAF or the AAF to exercise anything more than operational control over forces not of their own nationality.8 The Americans could point to the CCS decision of 1942 that a combined commander did not have power "to control the administration and discipline of any force of the United Nations comprising

--736--

his command, "beyond that "necessary for effective control."9 But this last phrase unhappily was vague enough to become the nub of the disagreement.

Having developed a complete administrative and logistical system of their own in the European theater and being convinced that the establishment of another administrative channel would serve to strengthen RAF controls, the Americans elected to meet the threat by indirection as well as by direct argument. Both Arnold and Eaker stressed the desirability of creating for Leigh-Mallory a small headquarters and pleaded that the AAF did not have the officers to staff a large one, an argument which certainly had some support in fact. Eaker pointed out that if a large headquarters were created with the full powers desired by the British, it would be 75 to 80 per cent British because of the inability of the Americans to provide an equal share of the staff. In such an event, the RAF would inevitably dominate the headquarters and British plans and policies would prevail. The British practice of assigning officers of superior quality to combined headquarters staffs and of always matching or exceeding in rank the American portion of the staff lent weight to Eaker's opinion. Experience argued that with RAF officers enjoying the advantage of one or two ranks over their opposite American numbers the latter would play a subordinate part.10

The Americans seem also to have been influenced in part by the British attitude toward proposals for bringing all air forces engaged in the strategic bombardment of Germany under one command. It will be recalled that, in December 1942, General Arnold had proposed an overall air command for Europe and Africa. A number of circumstances had combined to prevent serious consideration of the proposal, among them an apparent disinclination on the part of the RAF to endanger the integrity of its bombing operations under an existing arrangement which made the Bomber Command responsible directly to the Air Ministry and the Prime Minister. Revival of this proposal in the fall of 1943, together with an alternate proposal for a strategic air command to balance the tactical, brought a flat refusal to consider placing Bomber Command either under an over-all air command for the European and Mediterranean theaters or under an over-all command of the strategic air forces. For the time being, at least, the British even refused to agree that Bomber Command would come under the supreme commander for OVERLORD. British persistence at Cairo in November and December left an impression among the Americans of a purpose not only to

--737--

protect the independence of Bomber Command but to retain insofar as was possible strategic direction of the war in the Mediterranean, where British interests were great and where it had been agreed a British officer would succeed Eisenhower.11 Not until the spring of 1944 would the thorny question of control of strategic air forces to be employed in connection with the invasion reach a final settlement.

For so long as that question remained unsettled it naturally served to complicate the debate over control of the tactical air forces. Indeed, it had been in no small part Arnold's fear that Leigh-Mallory might seek to draw under his control strategic as well as tactical forces which had prompted the proposal in the fall of 1943 that there be a strategic air commander in addition to the tactical; as advanced by the Joint Staff Planners, both commands would come under the control of the supreme commander at an appropriate time.12 The question was not merely one of the control to be exercised over the heavy bombers during the course of the actual invasion. AAF leaders found in Leigh-Mallory's insistence that the launching of OVERLORD did not depend upon the successful completion of POINTBLANK the threat of a premature diversion of their forces from the bomber offensive.l3 Leigh-Mallory, who came to Washington early in November to speed the issuance of his directive, vigorously opposed the American draft as "unacceptable . . . in so far as it provided for both a strategic air commander and a tactical air commander under the control of the S. A. C."14 He felt that there should be only one air commander in chief for the operation and submitted a memorandum for consideration by the Combined Planners. His argument naturally served to confirm the suspicions of AAF officers.

Agreement on Leigh-Mallory's directive was reached by mid November. The Joint Staff Planners had objected that the British draft failed to limit sufficiently the "command functions of the Air Commander in Chief, A. E. A. F., with respect to the Ninth Air Force," and proposed that the transfer even of operational control of the Ninth to the new headquarters should be delayed in order that the medium bombers assigned to that air force might continue to help the Eighth in its strategic bombing. It was agreed that the air defense of the British Isles should come under AEAF,15 On the initiative of the Americans, who perhaps wished to emphasize the subordinate position of the new command, the directive was sent to COSSAC for issuance to Leigh-Mallory. General Morgan sent it down on 16 November.16

--738--

That directive named Leigh-Mallory air commander in chief, Allied Expeditionary Air Force under the supreme commander and gave him operational control over the British and American tactical air forces committed to OVERLORD. The RAF Tactical Air Force and the Air Defense of Great Britain, both of which organizations had been formed from the RAF Fighter Command, came under Leigh-Mallory's control at once; the Ninth Air Force would pass to that control on 15 December. Prior to the invasion the AEAF would lend maximum support to the strategic air offensive. An American officer would be appointed deputy air commander, and AEAF would interpret its powers in accordance with CCS 75/3. In other words, the administrative and disciplinary powers of the commander over U.S. forces under his control would be limited to those "necessary for effective control."17

An embryonic headquarters for AEAF had existed at Norfolk House since the summer. Maj. Gen. William O. Butler, former commander of the Eleventh Air Force in Alaska, was named on 17 November as deputy commander. Leigh-Mallory established his headquarters at Stanmore (former RAF Fighter Command headquarters located about a dozen miles northwest of the center of London), but offices were also retained in Norfolk House, where the closely coordinated planning of air, ground, and naval staffs continued to be concentrated under the direction of COSSAC.18 The new commander assumed administrative control of the RAF units assigned to the AEAF on 17 November.19 AAF units after passing to the control of AEAF would remain administratively responsible to the appropriate American headquarters, which currently was the United States Army Air Forces in the United Kingdom.

Provision of a definite number of American officers and men for the new headquarters was not made until December. On 18 December the American Component, Allied Expeditionary Air Force, was activated and assigned to the theater with a strength of 66 officers and 123 enlisted men, a strength about half that of the RAF component. General Butler had requested a larger number and COSSAC had indorsed the request, but no action resulted.20 Indeed, it became settled AAF policy to keep its side of AEAF headquarters small, as though thus to minimize its importance, but this tactic did not prevent the building of AEAF into a headquarters that by February 1944 would include some 250 RAF officers. It was admitted, of course, that the administrative responsibilities held by AEAF for RAF organizations provided some warrant for

--739--

this growth, but the Americans suspected a purpose to build up the only combined air headquarters then in existence to a point at which it might logically be argued that it alone was equipped to exercise a common command of the tactical and strategic air forces. This suspicion had become conviction by the following February, at least in the minds of some U.S. officers who advised an abrupt about-face from previous policy by strengthening the American component lest the worst come to pass.21 A small increase was subsequently authorized,22 but after it had been agreed in March that the strategic air commanders would separately answer to the supreme commander during the period of invasion, AEAF's demands for personnel came again to be regarded with the old indifference.

Leigh-Mallory conceived his chief functions to be to advise the supreme commander and his staff on air operations, to prepare the air plan for the invasion operation, to supervise the training of the tactical air forces, and to direct the tactical air forces in combat operations. To carry out these functions he organized his headquarters according to the RAF pattern. There were two main sections of the staff--the air staff and the administrative staff. The former, corresponding to the American A-2 and A-3 staff sections, was a combined staff, where British and American officers worked together closely in the collection of intelligence data, the preparation of plans, and the direction of operations. The administrative staff, on the other hand, was not a combined staff; it remained separated into American and British sections. The RAF side of this equivalent of the American A-1 and A-4 sections controlled the administration of the RAF units under the AEAF, while the U.S. side served merely to pass on necessary information to the Ninth Air Force. Leigh-Mallory's statement of policy indicated that because of the "high degree of integration of service elements into the Ninth Air Force the issuance by AEAF headquarters of administrative instructions to the Ninth Air Force regarding organization, movement, maintenance, supply, etc. will be the exception and not the rule."23

The Theater Air Force Again

The issue of a strategic air command had not been raised solely, or even primarily, for the advantage it seemed to offer with reference to the position and power of AEAF. Proposals for such a command stemmed partly from a growing concern over the lagging Combined Bomber Offensive and the desire to strengthen it in all possible ways.

--740--

It will be remembered that the CBO had been placed originally under the general strategic supervision of the chief of Air Staff, RAF, as deputy for the CCS, with whom the ultimate responsibility remained. Coordination of effort between the Eighth Air Force and RAF Bomber Command had been effected initially for the most part by the informal and intimate liaison maintained by the commanders concerned. More recently the Combined Operational Planning Committee, comprising representatives of the RAF's bomber and fighter commands and the Eighth Air Force, had been established for the purpose. In the fall of 1943 this committee was presided over by Brig. Gen. Orvil A. Anderson of the Eighth Air Force. Since the system in its actual operation exercised an effect chiefly on American operations, there was some feeling that a strategic air command embracing RAF and AAF bomber forces might better achieve the needed coordination of effort on POINTBLANK objectives.24 This feeling seems to have been held more strongly in Washington than in the theater.

In the theater AAF leaders, being reasonably content with the existing machinery for coordination of strategic operations with the RAF, paid closer attention to the problem of bringing the newly established Fifteenth Air Force into an effective system of control. This was also a subject of special concern to AAF Headquarters, which had taken the initiative in establishing the Fifteenth and looked forward, as at earlier dates, to closely coordinated operations between the United Kingdom and the Mediterranean which would exploit fully the flexibility inherent in the strategic air arm. According to a CCS directive the new force was to be used primarily in connection with POINTBLANK,25 but grave risk existed that under pressure of tactical circumstances the force might be diverted from its major mission unless placed directly within the command machinery established for the CBO.26 Planners were also concerned with the shifting of forces from one theater to another as the strategic situation required. There was talk of shuttle bombing and interchangeable use of bases between the Eighth and the Fifteenth. All of this would require unity of command rather than the liaison provided for in the establishment of the new air force.27

Accordingly, the U.S. chiefs of staff on 18 November 1943 placed a plan before the CCS to establish in the United Kingdom the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSAFE) for control of the operations of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces. General Spaatz, it was indicated,

--741--

would command this higher headquarters, and until such time as his command came directly under the supreme Allied commander, he would be responsible to the CCS and required to coordinate with the RAF through the chief of Air Staff, RAF.28

There were of course other if secondary considerations dictating the proposed course of action. General Arnold later admitted that a governing consideration had been the desire to build up an American air commander to a position with prestige comparable to that currently enjoyed by Air Chief Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command and General Eisenhower.29 And more fundamental, especially in their effect on the final organization of the new headquarters, were logistical and administrative considerations of the first importance. The organization and proper position of the logistical arm had long been a subject of debate in the Army and in the AAF. The demands of a war of machines fought over the whole face of the earth had dramatized as never before the importance of the essentially undramatic functions of transportation, supply, and maintenance and lent new strength to calls for centralization of responsibility. The service command had been a major problem of the Eighth Air Force since its establishment, and the anxious examination of the factors affecting the rate of bombing operations in the fall of 1943 had emphasized anew the basic importance of its varied functions.

If as a result of these investigations there were those who felt that the service command should be strengthened, that command itself was nowise loath to point out what should be done. On 24 October 1943, General Knerr became commanding general of VIII Air Force Service Command, succeeding General Miller, who took over the IX Air Force Service Command. Since the preceding July, when he assumed the duties of deputy commander of the service command, Knerr had pressed for a reorganization of the Eighth Air Force that would place logistics on the same level with combat operations.

Eighth Air Force organization had followed convention in placing the service command in a position subordinate to a headquarters staff in which an A-4 advised the commanding general on logistical problems, with a resulting conflict at times between staff office and operating agency. As a member of the Bradley committee in the spring of 1943, Knerr had prepared a special report on air service in Africa in which he advocated the elimination of this problem by the simple expedient of elevating the operating agency to the staff level of command. A-4 and

--742--

service command headquarters should be consolidated, and an air force headquarters should be organized around two deputies--one for operations and one for maintenance--"such deputies to execute a primary command function within their jurisdiction in execution of the Air Force Commander's decisions and policies." Knerr believed that a great amount of staff work and time could be saved if the air force commander and his two deputies, "in close personal contact and conversant with basic policies, could make major decisions on the spot as the rapidly changing situation of air warfare demands." He further argued that all service commands should be redesignated maintenance commands to escape the implication of subservience which went with the term "service."30

These ideas were embodied in specific recommendations for General Miller's attention immediately after Knerr's appointment as deputy commander of the service command. Miller forwarded the proposals to Eaker on 30 July, and these were followed in September by a Detailed plan.31 According to Knerr, as "difficulties developed in connection with A-4," General Eaker "gradually came around to the agreement that it would be better to consolidate A-4 and Service Command in one person, particularly since the headquarters were practically in the same building."32 On 11 October, therefore, Knerr was appointed A-4 of the Eighth Air Force. Although nominally still deputy commander of the service command, Knerr had known since mid-September that he would succeed Miller as commander.33 When this occurred in October, Knerr combined in one person the chief air service offices of the air force. By December the service command had absorbed the personnel and functions of A-4 to become in effect the sole logistical agency entitled to act in the name of the commanding general, Eighth Air Force.34

In his further efforts to centralize the responsibility for logistics, Knerr was aided by the course of events. The re-establishment of the Ninth Air Force in England had raised a question of the extent to which the provision of service and maintenance for the new air force should duplicate the already existing establishment--of how far the AAF should go toward maintaining two separate and independent service organizations. That question had been answered tentatively by the activation of the United States Army Air Forces in the United King dom as a theater air headquarters. Since the staff of this new headquarters was one and the same with the Eighth Air Force, General Knerr as

--743--

A-4 of the Eighth automatically became A-4 of USAAFUK and thus chief adviser to the theater air commander on questions of logistical organization. From the first he vigorously opposed unnecessary duplication.

Of necessity the VIII Air Force Service Command after the establishment of the Ninth Air Force functioned as a de facto theater service command, and its policies were shaped during the last weeks of 1943 by the assumption that it would be officially so designated. At the same time, air service headquarters looked forward to full integration with the highest air headquarters. Developments within the service command since summer, it will be recalled, had tended to divest the headquarters of direct control over operations and thus to shape it as an organization primarily responsible for policy.35 Increasingly, as operating responsibilities were transferred to the Base Air Depot Area, air service headquarters prepared itself to operate chiefly as a staff agency for the entire theater.

General Knerr recommended to Eaker the reorganization of USAAFUK with the two deputies for operations and for administration which he had proposed in his report on Africa.36 Recommendations by others advocated that Eaker separate himself from the Eighth Air Force to devote full time to a theater command with a small but strong headquarters staff. Attention was called to the growing competition between the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces, to the latter's tendency to duplicate almost all of the services provided by VIII Air Force Service Command (including the base depots), and to the apparent need for a theater air service command for "over-all planning, procurement and to supervise the operation of the Base Air Depot Area which should serve both Air Forces."37 Except for the appointment in late November of Maj. Gen. Ideal H. Edwards as deputy commander,38 however, Eaker waited for the final settlement of a variety of related command problems then under consideration.

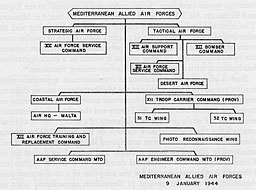

Mediterranean Allied Air Forces

Pertinent to any decision that General Eaker might have made on proposals for reorganization in ETO were developments which in the end would bring about his own transfer to the Mediterranean simultaneously with Spaatz' return to the top command in the United Kingdom. The decision to divert fifteen heavy bomber groups, formerly scheduled for the Eighth Air Force, to the Fifteenth and to use them

--744--

VII Air Force Service Command, December 1943

--745--

against POINTBLANK targets in close coordination with operations from England lent special importance to the question of the air command in the Mediterranean. Not only would the desired coordination with the new strategic command in ETO depend upon a close understanding between the commanders primarily concerned but the necessity, for administrative and other reasons, of fitting the Italy-based strategic force into the complex organization of Allied forces in the Mediterranean made General Eaker a most likely choice for a difficult assignment. Particularly important was the need for an AAF officer of high rank and proved ability in the diplomacy of combined operations to take the command of the projected Mediterranean Allied Air Forces.

The advance of the Allied forces from Africa to Sicily and then to Italy had made necessary several adjustments of organization and jurisdiction. It was felt that there should be one supreme command for the whole of the Mediterranean, and that the air forces should be similarly united so as to insure full coordination of the theater's far-flung air elements. There had been, of course, Mediterranean Air Command under Tedder since the preceding February. But this command had existed primarily for the coordination of operations among Northwest African and Middle East air forces, and with the increasing consolidation of these forces for all practical purposes, there had arisen a question as to the advantage in maintaining two such headquarters as MAC and NAAF when one headquarters might serve well enough. Early in December, at the SEXTANT conference in Cairo the British chiefs of staff proposed to extend the responsibility of the commander in chief of Allied Force to include the Balkans, the Aegean Islands, and Turkey and to make him in effect commander of the Mediterranean area. At the same time it was proposed, on Tedder's recommendation, that MAC be redesignated Mediterranean Allied Air Forces on the understanding that it would absorb the functions theretofore exercised by NAAF headquarters. Among the arguments advanced for the latter proposal, some of them attributed to Doolittle, were the inappropriateness of the current designation for the ranking air headquarters and the fact that under that name it had come to be identified as a British organization to the detriment of Anglo-American good will. Of greater weight were the advantages to be gained by consolidating MAC and NAAF.39

The Combined Chiefs, having accepted the proposals, on 5 December issued a comprehensive directive for the organization of "a unified

--746--

command" in the Mediterranean.40 This paper placed air and sea commanders on the same level with the commanding general of the 15th Army Group under the commander in chief of Allied Force. MAAF would direct operations through a single combined operational staff for the assurance of true unity in planning and action by its AAF and RAF elements. For purposes of administration, however, the headquarters would be divided into three staffs headed respectively by a deputy air commander in chief (United States), a deputy air commander in chief (British), and an air officer commanding in chief (Middle East). Thus each of the three elements would control its own administration as its organization or position might require. To facilitate the administration of American units, now divided between the Twelfth and Fifteenth Air Forces, the United States Army Air Forces, North African Theater of Operations was created (USAAF/NATO).

The CCS had agreed that the new organization of Allied forces in the Mediterranean should become effective on 10 December 1943. Actually MAAF was not activated until ten days later, but as of 10 December41 Under it, which is to say under the air commander in chief, Mediterranean, fell all air organizations in that area: USAAF/NATO, all RAF elements including RAF, Malta and RAF, Middle East,* French and Italian units operating within the area, and such other forces as might later be assigned to it.42 The CCS had directed that the commander in chief, Allied Force should furnish the Fifteenth Air Force with necessary logistical and administrative support "in performance of Operation POINTBLANK as the air operation of first priority." In the event of "a strategic or tactical emergency, "he might at his discretion use the Fifteenth for purposes other than its primary mission on the condition that he inform the CCS "and the Commanding General, U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, if and when that command is organized."43 Tedder on 20 December became air commander in chief with Spaatz as his operational deputy. The latter on that same day assumed the duties of commanding general, USAAFINATO.44 It was understood, however, that these assignments were temporary. In fact, a final decision on the transfer of Spaatz to

* Middle East now ceased to operate as an autonomous area. U.S. Army Forces in the Middle East (USAFIME) came under the operational control of the commander in chief, Mediterranean, for such operations as might be conducted in the eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans, or Turkey but remained responsible to the War Department for other functions assigned to it. It will be recalled that the Ninth Air Force, combat air element of USAFIME, had been transferred to the United Kingdom with its combat units going to the Twelfth Air Force.

--747--

England and the reassignment of Eaker to the command of MAAF had already been reached.

At Cairo, on 5 December, Roosevelt had decided on Eisenhower as the supreme Allied commander for OVERLORD.45 General Marshall, who up to the last minute had been considered the most likely choice, would remain as U.S. Chief of Staff, a position in which he was regarded by the President as indispensable. Eisenhower received notification of his new assignment from Marshall on 7 December.46

On that same day, the Combined Chiefs accepted the American plan for a strategic air command to coordinate the operations of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces.47 The British chiefs had vigorously objected to the proposal. The plan took the daylight bombing forces out of the province of the chief of Air Staff, RAF, as coordinating agent of the CCS, and thus in the British view destroyed, without compensating advantages, existing arrangements for close liaison between AAF and RAF leaders. The British chiefs admitted that the possibility of switching heavy bombers between theaters was "attractive" but argued that the plan was unrealistic, given existing base and maintenance facilities in Italy. In response to these objections, the U.S. chiefs agreed that Portal should continue to act for the CCS pending a further decision on control of all strategic air forces in connection with OVERLORD. Under Portal's direction, the American air commander would be responsible for the determination of POINTBLANK target priorities for the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces and for the techniques and tactics employed by them. He would have authority to move units of either force between the two theaters within the limits of available base area facilities and would keep the Allied commander in chief in the Mediterranean informed of his general plans and requirements. In an emergency the respective theater commanders would be empowered at their discretion to use the strategic air forces for purposes other than POINTBLANK.48

Without agreeing in principle, the British chiefs of staff accepted the amended plan as one applying primarily to U.S. forces, and Portal agreed to carry out the duties of general coordinator of CBO operations with which he remained intrusted.49 The establishment of the new strategic air command thus did not materially alter the general principle of strategic control originally established for the CBO. A new headquarters would be interposed between the operating forces and the chief of

--748--

Air Staff, RAF and would become the interpreter of over-all strategic policy for those forces.

On 8 December, the day after the decision on the new command, General Arnold personally conveyed the news to Spaatz, together with the information that Spaatz would command the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe.50 It had been generally assumed since mid-November that he would be selected. Senior to Eaker and from the first of the war to its end at Nagasaki regarded by Arnold as his top combat commander, Spaatz was the natural choice for leader in the climactic operations against Germany. The selection at Cairo of Eisenhower, with whom Spaatz had worked in close and effective association since before the invasion of North Africa, provided whatever additional argument may have been required.

Arnold discussed the reorganization with Spaatz and his commanders on the 9th. General Spaatz expressed the hope that he might take his staff with him to England and recommended that Eaker be brought to the Mediterranean as air commander in chief, that Doolittle take over the Eighth Air Force, and that Cannon succeed Spaatz in command of the Twelfth.51 This slate, with the addition of Maj. Gen. Nathan F. Twining for the command of the Fifteenth, proved to be the one finally adopted.

Following his return to Washington, Arnold notified Eaker on 18 December of the command assignments agreed upon as a result of the organizational changes made at Cairo.52 It had been decided by that date that Tedder would leave the Mediterranean to become Eisenhower's deputy; a British officer, Gen. Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, would succeed Eisenhower in the Mediterranean. With the MAAF command allotted to the Americans, the situation required, as Arnold pointed out to Eaker, a man especially qualified by experience and ability. General Arnold's message emphasized Eaker's successful handling of relations with the British.

Eaker himself had hoped that he might remain in command of the Eighth under Spaatz. As he said to Arnold in a message of 19 December, it was "heartbreaking to leave just before the climax."53 On the same day he sought by radio to ascertain Spaatz' views on that possibility.54 There were others--particularly Devers--who felt that Eaker should remain with the Eighth Air Force.55Eaker's long experience in England and Doolittle's experience in Northwest Africa and the Mediterranean naturally suggested a reversal of the proposed assignments for the two

--749--

men. But Arnold and Spaatz were agreed that Eaker could render greater service as air commander in the Mediterranean.56 On 22 December, The Adjutant General issued the necessary orders.57 If Arnold's dissatisfaction over the rate of Eighth Air Force operations entered into the decision, the record apparently has left no evidence of it.

Spaatz' orders were effective immediately, Eaker's upon the relief of Tedder. The orders were promptly amended to postpone Eaker's departure from ETO until he had given the benefit of his counsel to Spaatz and Doolittle in England. Consequently, he and his deputy, Air Marshal Sir John C. Slessor, did not reach the Mediterranean until mid-January.58

Tedder and Spaatz had left the final organization of MAAF for determination by the new commander,* but substantial adjustments in the organization of AAF elements had been accomplished under a NATO-USA directive of 22 December. Effective 1 January 1944, USAAF/NATO became Army Air Forces, Mediterranean Theater of Operations (AAF/MTO). XII Air Force Service Command,† which since the establishment of the Fifteenth Air Force had served as a de facto theater service command for American organizations, became the Army Air Forces Service Command, Mediterranean Theater of Operations (AAFSC/MTO). The I Air Service Area Command remained under AAFSC/MTO, but II and III Air Service Area Commands were converted, respectively, into the XV Air Force Service Command and the XII Air Force Service Command. XII Air Force Engineer Command (Prov.) moved up, still in a provisional status, to become AAFEC/MTO. The Twelfth's training command retained its old numerical designation but was now XII Air Force Training and Replacement Command.59

As commanding general, AAF/MTO, Eaker would have directly

* On 27 December, MAAF issued an organization memorandum with the following instructions "pending full activation" of that headquarters: Headquarters, MAC, Algiers would relinquish its title and assume the title of Headquarters, MAAF (Rear), with responsibility for war organization (until MAAF [Advance] assumed the function) and for planning, maintenance and supply, and AFHQ liaison. Headquarters, NAAF, and Air Command Post (an advance headquarters at La Marsa, near Tunis) were combined under the new title of Headquarters, MAAF (Advance). The element would be responsible for all air staff duties other than those specifically assigned to MAAF (Rear) and for RAF administration in Northwest African, Central Mediterranean, and Malta Air Forces. The administration of RAF units in the Middle East would continue under Headquarters, RAFME, until the MAAF staff had been filled.

† The North African Air Service Command, of which XII AFSC had been the American element, now ceased to exist.

--750--

under him for administration of American units five major headquarters: Twelfth Air Force, Fifteenth Air Force, AAFSC/MTO, AAFEC/MTO, and the 90th Photo Reconnaissance Wing. As air commander in chief, Mediterranean, he would direct the operations of MAAF through subordinate combined headquarters which were changed now only in name. The well-established Strategic, Tactical, and Coastal Air Forces became MASAF, MATAF, and MACAF,* and photo reconnaissance headquarters became the Mediterranean Allied Photo Reconnaissance Wing. Except for changes in units subordinate to the larger headquarters, the organization fixed upon in January 1944 would continue to the end of the war.

Mediterranian Allied Air Forces, 9 January 1944

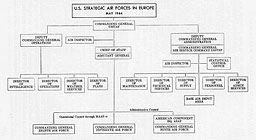

United States Strategic Air Forces

Several of the changes effected by NATOUSA's directive of 22 December 1943, notably the creation of a theater air service command in the Mediterranean, were suggestive of General Knerr's proposed reorganization in ETO. It would seem, however, that General Spaatz

* Twining, who had commanded the Thirteenth Air Force in the Pacific and took command of the Fifteenth Air Force in January 1944, served also in command of the MASAF. Similarly, Cannon, who was moved 'up to command of the Twelfth Air Force, commanded MATAF. AVM Hugh P. Lloyd continued in charge of MACAF.

--751--

was thinking, in advance of his arrival in England, along somewhat different lines. Discussions with members of his staff, on 24 December, of the administrative and operational responsibilities of his new command revealed a primary and natural concern for the effective coordination of bombing operations. He had apparently decided to set up a normal "A" staff organization with a few additional staff sections, and it was clear that he contemplated a small headquarters whose chief function would be to issue "broad orders and directives" to the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces, after coordination with the Air Ministry. The new headquarters would engage in strategic planning and the selection of targets, the setting of policies with regard to combat crew tours of duty, and the movement of personnel and equipment between the two headquarters. In other words, it would be a small operational headquarters with supervisory and policy-making functions.60

Such a plan of course overlooked considerations apparently more readily grasped in England than in the Mediterranean--among them the need for administrative controls to prevent unnecessary competition between the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces and the advantage with reference to AEAF in the prompt establishment of a strong American headquarters for the administrative control of the Ninth.* The unusual combination of responsibilities anticipated for the new command--administrative control of both strategic and tactical air forces in the United Kingdom and operational direction of both the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces--argued for the adoption of a two-deputy plan. Accordingly, when on 30 and 31 December, immediately after his arrival in England, Spaatz met with Eaker, Knerr, Chauncey, and Doolittle to discuss the organization of the new headquarters, it was decided that Spaatz would have a deputy for administration with jurisdiction over the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces and a deputy for operations to direct the strategic operations of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces. Agreement was also reached on the establishment of a theater air service command. Eighth Air Force headquarters would become the new strategic air command headquarters, and VIII Bomber Command headquarters would become the new Eighth Air Force headquarters.

* Actually, before he left North Africa on 29 December, Spaatz had come around to the belief that he would have to set up a larger headquarters In order to admIn1ster both the Eighth and the Ninth.

† In fact, VIII Bomber Command in the following reorganization ceased to exist, the Eighth Air Force thereafter dealing directly with the bombardment divisions. VIII Fighter Command continued.

--752--

U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, May 1944

--753--

The new organization, its Details having been perfected, was approved by Maj. Gen. Walter B. Smith, representing Eisenhower in England, on 1 January and by AAF Headquarters on 4 January.62 On the next day Spaatz received from the Joint Chiefs of Staff authority to establish the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSTAF) as of 1 January 1944. On6 January, General Order No. 1 appointed Maj. Gen. Frederick L. Anderson, theretofore commanding general of VIII Bomber Command, and Brig. Gen. Hugh J. Knerr as deputy commanders for operations and administration, respectively. Two days later the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, Eighth Air Force took leave of Bushy Park (WIDEWING) for High Wycombe, where General Doolittle was forming a new Eighth Air Force headquarters with the staff of the disbanded VIII Bomber Command as a nucleus. Most of the former staff officers of the Eighth remained at WIDEWING to serve in the new USSTAF headquarters.63 On 18 January, General Eisenhower as theater commander gave the final legal sanction by delegating to USSTAF administrative responsibility for all U.S. Army air forces in the United Kingdom, a responsibility formally assumed by Spaatz on 20 January.64

On the operational side, the command structure now existing was simple enough. The Ninth Air Force remained under the operational control of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force. As for the strategic operations of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces, General Anderson acted in behalf of Spaatz for their coordination.

On the administrative side, the story is more complex. General Knerr at one and the same time served as deputy commanding general for administration, USSTAF, and as commanding general, Air Service Command, USSTAF. The VIII Air Force Service Command headquarters became the Air Service Command, USSTAF headquarters, with the Base Air Depot Area as its chief component. The Strategic Air Depot Area became the new VIII Air Force Service Command, with headquarters at Milton Ernest. Like the IX Air Force Service Command, it operated under the technical control of the Air Service Command, USSRAF, which provided base services for both commands.65 Of assistance in putting the new plan into effect was the fact that VIII Air Force Service Command headquarters, like that of the Eighth Air Force, had been located at Bushy Park. The changeover there was consequently

* The official abbreviation of the new headquarters was USSAFE until it was changed to USSTAF on 4 February 1944.

--754--

for the most part a matter of drafting the necessary papers. The commanding general of USSTAF, the deputy for operations, and the whole of the latter's staff were assigned to the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, USSTAF. The deputy for administration, with staff, drew an assignment to the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, Air Service Command, USSTAF.66

General Knerr functioned in a dual capacity. As deputy for Spaatz he exercised a theater-wide authority over logistical questions; as commanding general of the air service command he directed the operation of its components in his own right. Actually, so much of the supervision of air service operations had been delegated to the Base Air Depot Area that Knerr was able to emphasize the advisory and policy-making functions of the deputy commanding general. There was of course a certain amount of confusion: if the general himself was never bothered by the question of which hat he wore, the same cannot be said of his staff. Subordinate headquarters also found cause for bother in this unorthodox organization.67 But such minor difficulties were easily overshadowed by the recognition won for logistics as the legitimate partner of operations.

General Spaatz retained a chief of staff, but the office had been shorn of most of its normal duties. Only the adjutant general and the air inspector were responsible to the chief of staff, who headed in effect a secretariat for the commanding general.68 In accordance with Knerr's recommendations, the major staff sections were designated directorates. Under the deputy commanding general for operations initially only two directorates existed-those for operations and for intelligence. Eventually, weather and plans sections would be added.69 USSTAF, ADMIN, with separate directorates for personnel, supply, maintenance, and administration, constituted the greater part of the headquarters.* The director of personnel combined the usual functions of A-1 with certain responsibilities for organization and movement taken over from the directorate of operations. Under the director of administration were united several former special staff sections-such as quartermaster, chemical, signal, ordnance, engineer, and medical. Knerr retained directly under him the statistical control office for assistance with organizational planning and control of reporting.70

The reorganization of January 1944 integrated operations and logistics

* A directorate of technical services was added in February.

--755--

in one headquarters to a degree never before attained and represented a triumph for the concept that logistics was of equal importance with operations. Few if any airmen would maintain that the ideal organization had been achieved in USSTAF, whether the view be that of its internal structure or its relative position in the over-all command of U.S. forces, but it came nearer the theater air force repeatedly advocated by Arnold and Spaatz than any headquarters yet established. And as with MAAF, it would serve until the victory had been won.

--756--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (21) *

Appendix

Notes to Chapter 22:

1. This is particularly evident in the minutes of the CCS and JCS during 1943.

2. CCS 113th Mtg., 20 Aug. 1943; Henry L. Stimson and McGeorge Bundy, "Time of Peril," in Ladies Home Journal, Jan. 1948, pp. 96-97. Roosevelt told Stimson at Quebec that Churchill had come to him and "offered to accept Marshall for the OVERLORD operation." Churchill said that he had previously promised the position to the chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Alan Brooke.

3. CCS 113th Mtg., 20 Aug. 1943.

4. 8th AF Commanders' Mtg., 10 Sept. 1943, p. 2.

5. AFSHO Special File 77 (ltrs.).

6. Memo for CG 8th AF from Brig. Gen. Robert C. Candee, 3 Sept. 1943; ltr., Gen. Eaker to CG ETOUSA, 10 Sept. 1943; JCS 118th Mtg., 12 Oct. 1943, Supplementary Minutes.

7. Memo for Portal from Arnold, 20 Aug. 1943, and incl.; ltr., Candee to CG 8th AF, n.d. but prob. late Aug. or early Sept. 1943; ltr., Arnold to Portal, 6 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to Portal, 8 Sept. 1943; ltr., Gen. Devers to C/S U.S. Army, 11 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to Leigh-Mallory, 13 Sept. 1943; Extract from Minutes, CPS 89th Mtg., 4 Nov. 1943.

8. Ltr., Arnold to Portal, 6 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to Portal, 8 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to CG ETOUSA, 10 Sept. 1943; ltr., Devers to C/S U.S. Army, 11 Sept. 1943.

9. CCS 75/3, 24 Oct. 1942. This subject was discussed at meetings of the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff.

10. Ltrs., Devers to C/S U.S. Army, 6 July, 11 Sept. 1943; ltr., Candee to CG 8th AF, 3 Sept. 1944 ltr., Eaker to Portal, 8 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to CG ETOUSA, 10 Sept. 1943. See also address given at Hq. AAF by Col. Philip Cole, Hq. 9th AF, "Air Support of OVERLORD," 8 Aug. 1944.

11. Memo for Gen. Marshall from Maj. Gen. T. T. Handy, AC/S OPD and 5 incls., 4 Oct. 1943; memo for Marshall from Handy, 10 Nov. 1943; memo for Sec. JCS from Col. W. T. Sexton, Sec. WDGS, and incl., 5 Nov. 1943; Extract from Minutes, CCS 124th Mtg., 22 Oct. 1943; JCS 121st Mtg., 2 Nov. 1943, Supplementary Minutes, p. 4; msg. COS (4) 941, COS to Joint Staff Mission, 10 Nov. 1943; JCS 123d Mtg., 15 Nov. 1943, pp. 3-6; CCS 400/1, 26 Nov. 1943; CCS IHd Mtg., 4 Dec. 1943; Minutes of Meeting between the President and the Chiefs of Staff Held on Board Ship in the Admiral's Cabin on Friday 19 Nov. 1943 at 1500.

12. Extract from Minutes, CCS I24th Mtg., 22 Oct. 1943; Directive to Air C-in-C AEAF, Report to the Joint Staff Planners, 18 Oct. 1943.

13. For example, see Minutes of COSSAC Staff Conf., 28 Aug. 1943; CPS 86th Mtg., 25 Oct. 1943; File 706, 3 Jan. 1944.

14. Extract from Minutes, CPS 89th Mtg., 4 Nov. 1943.

15. Ibid.

16. CCS 304/3, 19 Oct. 1943; CCS 124th Mtg.,22 Oct. 1943; CM-OUT-7211, Marshall to Devers and Eaker, 18 Nov. 1943.

17. Ltr., Lt. Gen. F. E. Morgan, C/S SC (Designate) to AM Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Directive to Air Commander in Chief, AEAF, 16 Nov. 1943.

18. Memo, Hq. AEAF, 17 Nov. 1943.

19. AFSHO Special File 77 (ltrs.).

20. Ltr., CG ETOUSA to CO American Component, AEAF, 30 Dec. 1943; memo for AC/S G-1, Hq. ETOUSA from Gen. Butler, 26 Nov. 1943; msg. W-9170, ETOUSA to AGWAR, 3 Jan. 1944.

21. 1st ind.(ltr., Gen. Barker, Hq. COSSAC to CG ETO, 28 Nov. 1943), Gen. Devers to AG, U.S. Army, 30 Nov. 1943; ltr., Spaatz to Arnold, 1 Feb. 1944; memo, AC/AS, Plans, 22 Feb. 1944; File 706, 19 Feb. 1944. See Lewis H. Brereton, The Brereton Diaries (New York, 1946), p 227.

22. Hist. Data, American Component, AEAF, p. 20. As of 3 June 1944, the RAF strength was 1,001 assigned and attached as compared with 502 Americans. (See Hq. AEAF, AEAF Personnel Data, 3 June 1944.)

23. Ltr., AOC-in-C AEAF to Hq. COSSAC, 20 Dec. 1943.

24. Ltr., F. L. Anderson to Eaker, 20 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to Spaatz, 11 Sept.; 1 Oct. 1943; memo for Arnold from Marshall, 5 Nov. 1943; memo from Eaker, 26 Nov. 1943; JCS 125th Mtg., 18 Nov. 1943.

25. Msg. FAN 254, CCS to CG ETO, 23 Oct. 1943, implementing CCS 217/1.

26. JCS 125th Mtg., 18 Nov. 1943 (ref. JCS 602/1); File 77 (1m.).

27. JCS 601, 13 Nov. 1943; CCS 400, 18 Nov. 1943. Cf.CCS 217/1, 19 Oct. 1943; FAN 254 cited in n. 25.

28. CCS 400/1, 26 Nov. 1943.

29. Ltr., Arnold to Spaatz, n.d.

30. Ltr., Knerr to CG ASC, 23 June 1943.

31. Ltr., Knerr to CG VIII AFSC, 26 July 1943; memo for CG 8th AF from Miller, 30 July 1943; ltr., Eaker to Miller, 10 Aug. 1943; ltr., Miller to CG 8th AF, 14 Sept. 1943, and 3 incls.

32. Interview with Gen. Knerr by Capt. A. Goldberg, asst. historian, USSTAF, 12 June 1945, p. 1.

33. 8th AF Commanders' Mtg., 10 Sept. 1943; ltr., Eaker to Frank, 13 Sept. 1943; Hq. 8th AF.GO 182, 11 Oct. 1943.

34. Hq. 8th AF GO 182; Hq. VIII AFSC GO 45, 24 Oct. 1943; Hq. VIII AFSC Office Memo 39, 29 Nov. 1943; memo for AG, Plans, Chief of Administration from Knerr, Hq. VIII AFSC, 3 Dec. 1943.

35. Hq; VIII AFSC Memo 160-13A, 4 Sept. 1943; memo for C/S VIII AFSC from Knerr, 3 Sept. 1943.

36. Knerr interview.

37. Ltr., Col. C. P. Cabell to Gen. Eaker, 22 Nov. 1943. See also memo for Col. D. H. Baker, Chief, Plans and Stat. Office, Hq. VIII AFSC from Col. J. A. Laird, Jr., 4 Oct. 1943.

38. Hq. 8th AF GO 211, 22 Nov. 1943.

39. CCS 387, 3 Nov. 1943; CM-IN-4198, Doolittle sgd. Eisenhower to Arnold for Spaatz,7 Oct. 1943; La Marsa Conference (of American and British air officers), Oct. 1943.

40. CCS, 131st Mtg. (26 Nov. 1943), 135th Mtg. (5 Dec. 1943); CCS 387/3, 5 Dec. 1943.

41. CCS 138th Mtg., 7 Dec. 1943; CCS Msg. O24046; Hq. AFHQ GO 67, 20 Dec. 1943.

42. Hq. AFHQ GO 67, 20 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-8353, Marshall to Eisenhower and Royce, 22 Dec. 1943.

43. CCS 387/3, 5 Dec. 1943.

44. CM-OUT-7103, Arnold to Devers for Portal, 18 Dec. 1943; History, AFHQ, Pt. 3, Sec. I, p. 652; CM-OUT-8843, Ulio to CG NATO, 22 Dec. 1943; Administrative History, 12th AF, Volume I, Pt. III; CM-OUT-8490, Marshall to Eisenhower, 22 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-10287, Marshall to Eisenhower, 28 Dec. 1943; CM-IN-14359, Spaatz to AGWAR for Arnold, 22 Dec. 1943; CM-IN-14751, Eisenhower to AGWAR, 23 Dec. 1943.

45. Robert E. Sherwood, "The Secret Papers of Harry L. Hopkins," in Collier's, 28 Aug. 1948, p. 75.

46. H.Co Butcher, My Three Years with Eisenhower (New York, 1946), p. 454.

47. CCS 138th Mtg., 7 Dec. 1943.

48. CCS 400/1, 26 Nov. 1943; CCS 400/2, 4 Dec. 1943; CCS 1 Bd Mtg., 4 Dec. 1943.

49. CCS 138th Mtg., 7 Dec. 1943.

50. File 706.

51. Ibid., 9 Dec. 1943.

52. CM-OUT-R7075, Arnold to Eaker, 18 Dec. 1943.

53. CM-IN-12181, Eaker to Arnold, 19 Dec. 1943.

54. Unnumbered msg., Spaatz to Arnold, 19 Dec. 1943.

55. CM-IN-W8720, Devers to Arnold, 20 Dec. 1943.

56. CM-OUT-5296, Arnold to Spaatz, 20 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-7695, Arnold to Eaker, 20 Dec. 1943; File 706.

57. CM-OUT-R7248, Ulio to Eaker, 22 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-5575, Ulio to Spaatz, 22 Dec. 1943.

58. CM-OUT-8843, Ulio to CG 83 6 NATO, 22 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-8844, Ulio to CG ETO, 22 Dec. 1943; CM-OUT-10288, Marshall to Devers, 28 Dec. 1943; msg., AGWAR to ETOUSA and Algiers, 28 Dec. 1943, cited in History, MAAF, 10 Dec. 1942--1 Sept. 1944, Volume II; History, AFHQ, Pt. 3, Sec. I, p. 652.

59. 59. History, MAAF, Volume II; CM-IN326, Adv. Hq. MAAF sgd. Eisenhower for AGWAR et al., 31 Dec. 1943; CM-IN-13928, Air Comd. Post to Air Ministry et al., 22 Dec. 1943; CM-IN-6374, Eisenhower to AGWAR, 10 Dec. 1943; History, AFHQ, Pt. 3, Sec. 1, pp. 652-53, 657; Organizational Memos I (1 Jan.), 3 (7 Jan. 1944), cited in History, MAAF, Volume II; Administrative History, 12th AF, Pt. I; History, Original IX AFSC, p. 220; History, AAFSC/MTO, 1 Jan.--30 june 1944; History, XII AFSC; History, 15th AF (Rev.); Hq.AAF/MTO GO 1, 1 Jan. 1944; Adv. Directive, NATOUSA, 22 Dec. 1943.

60. 60. Notes of Conference Held at La Marsa, North Africa, 24 Dec. 1943, in File 706.

61. File 706.

62. CM-IN-548, ETOUSA to AGWAR (Smith to WAR and Eisenhower), 1 Jan. 1944; notes, teletype conf. WD-TC118, Spaatz and Giles, 4 Jan. 1944.

63. CM-OUT-1273 (JCS 71469), AGWAR to USFOR (Washington to London), 5 Jan. 1944; Hq. USSAFE GO 1, 6 Jan. 1944; Hq. 8th AF GO 6, 8 Jan. 1944.

64. Hq. ETOUSA GO 6, 18 Jan. 1944; Hq. USSAFE GO 6, 20 Jan. 1944.

65. Minutes, Hq. VIII AFSC Staff Mtg. 117, 7 Jan. 1944; notes on mtg., Hq. VIII AFSC, 9 Jan. 1944; Hq. USSTAF GO 12, 1 Mar. 1944.

66. ASC-USSTAF Organization Manual, 1 Mar. 1944.

67. Memo for Col. J. Preston from Maj. A. Lepawsky, 4 Mar. 1944; memo for Gen. Knerr from Preston, 2 June 1944

68. USSTAF organization chart, 12 Feb. 1944; interview with Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz by B. C. Hopper, 20 May 1945.

69. Hq. USSTAF GO 9, 12 Feb. 1944; ltr., Gen. Anderson to Brig. Gen. C. P. Cabell, Hq. USSTAF, 22 Apr. 1944; USSTAF organization chart, 12 Feb. 1944.

70. Hq. USSTAF organization charts, 21 Jan., 12 Feb. 1944; ASC-USSTAF organization manual, 1 Mar. 1944