Chapter 11

THE AAF'S LOGISTICAL ORGANIZATION

IN ADDITION to determining the types and numbers of planes required for the fulfillment of its mission, the AAF had to develop an organization for logistical support of its combat forces. The term logistics has a variety of connotations. It could be interpreted so as to signify all the subjects included in this section of the narrative, but in this chapter the term will be used to denote only those services of supply and maintenance necessary for support of combat units. To provide these services on the scale required and within the time limits fixed by strategic schedules imposed upon the AAF one of its heaviest burdens. It was necessary to develop within the United States a vast organization for the procurement, storage, and distribution of an almost infinite number of both stock and special items of supply; to provide the means for channeling these supplies to widely scattered combat areas; and to organize, equip, and train a variety of service units for assignment overseas. The Army's Services of Supply could be counted upon for the provision of "common use" items--such things as uniforms and food--and the several technical services procured critical items of equipment and ordnance. But the supply of items peculiar to an air force was, in general, the responsibility of the AAF, which was also carrying the full responsibility for maintenance services.

Fortunately, the Air Corps did not have to start from scratch. The special characteristics of the airplane as a military weapon had from the first demanded somewhat unusual arrangements for its accommodation within the armed services. Adjustments to this necessity had never proceeded at the rate airmen felt desirable, but the Air Corps was the only component of the U.S. Army whose mission combined

--362--

both combat and logistical functions. Unlike their fellow officers in the Infantry or the Field Artillery, air officers had long been accustomed to control the procurement of their weapons and in large part to direct the logistical machinery on which the weapon's effective employment depended. The experience thus gained stood the AAF in good stead when it grappled with the problems of an enormous expansion.

Prewar organization had also already given to the Air Corps an essential prerequisite for its future autonomy. In 1939, and even in 1941, the hard-pressed leaders of the AAF had little inclination to assume the additional burdens that would have come with a transfer of responsibilities traditionally belonging to the Army's technical and supply services. But as the war progressed and the RAF's own organization matured, there naturally developed a growing inclination to free itself from dependence upon other organizations. By the war's end the AAF had gained a large share of the control over provision of the communications equipment, ordnance, and fuel used by its own forces; in other words, it had acquired significant responsibilities theretofore belonging to the technical services. In so doing, the AAF had also developed its autonomy at the expense of the Army Service Forces. Whatever else may be said of these developments, they unquestionably facilitated the postwar transition of the AAF to the status of a separate service.

The Air Service Command

From 1926 to 1942 the Materiel Division of the Office of the Chief of Air Corps (OCAC) was largely responsible for all operations of the AAF's logistical system. With headquarters at Wright Field and only a small liaison office in Washington, the Materiel Division through appropriate subsections administered the Air Corps' procurement and development programs, and through its Field Service Section (FSS) exercised ultimate responsibility for supply and maintenance within the Air Corps. The FSS controlled four major air depots located at San Antonio, Texas; Fairfield, Ohio; Middletown, Pennsylvania; and Sacramento, California.* The overseas air depots in Panama, Hawaii, and the Philippines came under the jurisdiction of the local departmental commands, with FSS acting only in an advisory capacity.1 Direct control by the FSS thus extended only to the

* Before 1937 this depot had been at Coronado, California.

--363--

four continental air depots, which stocked and distributed Air Corps supplies and overhauled and repaired aircraft for operating units. The provision of immediate service and maintenance for combat units on Air Corps bases fell to military organizations normally under the direct control of the base commanders. These bases received their supplies from the Field Service depots and could look to those depots for assistance in maintenance.2

The division of function corresponded closely with and resulted from that separating the Air Corps and the GHQ Air Force. The Chief of the Air Corps had responsibility for production, procurement, storage, issue, and maintenance of all aeronautical equipment and supplies used by the Air Corps and not specifically required to be furnished by the Army's other supply services. The OCAC was also responsible for prescribing the rules and regulations governing procurement, production, storage, issue, test, maintenance, and techniques of operation relating to the equipment and supplies it furnished.3 But the GHQ Air Force, since its organization in 1935, had enjoyed control over supply and maintenance services on its operating bases. Jealous of this control, GHQ Air Force resisted encroachments by OCAC agencies.4 and successfully restricted FSS to technical supervision of the work on combat bases. This supervisory right was in itself limited to the issuance of general instructions pertaining to procedures and methods, and to a right of inspection without command authority. The situation, in short, reflected the dualism running throughout Air Corps organization at that time.

In November 1940 FSS proposed that the jurisdiction of the Materiel Division be extended to include control of supply and maintenance on all GHQ Air Force bases and stations. Only first echelon services, those actually performed by constituent elements of the combat unit, would be exempt from this control. Supply channels had also been complicated by the necessity to go through the Army's corps areas, under which all Air Corps units operated, and it was now proposed that supplies be moved directly from the Field Service depots to stations, with the Air Corps organization exercising complete responsibility all the way down to the supply agencies on combat stations. A further proposal for centralization of responsibilities called for the assignment of representatives of the Army technical services to FSS in order to effect closer coordination in all matters involving the technical services.5 This proposal, however, failed to carry.

--364--

In December 1940 the Plans Division of OCAC recommended establishment of a "Maintenance-Supply Command" that would be built around the core of the Field Service Section and would operate through four wings--one to be located in each of the proposed air districts that were to be established in the following January.* After further discussion during the winter, the Air Corps on 15 March 1941 activated a provisional Air Corps Maintenance Command which became permanent on 29 April with War Department approval of the plan. But the new Maintenance Command, whose establishment marked a significant step toward the separation of functions formerly belonging to the Materiel Division, had its jurisdiction limited, in compliance with GHQ Air Force's recommendation that, except for technical supervision, the command's responsibilities for supply and maintenance "stop at the boundary of the Air base."6 With headquarters at Wright Field, the Air Corps Maintenance Command included the old Field Service Section, the 50th Transport Wing, and six depots--the four at Fairfield, Middletown, San Antonio, and Sacramento; and two new ones at Mobile, Alabama, and Ogden, Utah. In July four maintenance wings were organized in the interest of a greater decentralization of operations.7 On Air Corps stations, as distinct from those belonging to GHQ Air Force, the command proceeded to establish subdepots equipped to handle third echelon supply and maintenance.† The establishment of the Army Air Forces on 20 June 1941 and exemption of all Air Corps installations from corps area control on 1 July greatly aided the command in this development. But the Air Force Combat Command, which replaced GHQ Air Force under the new organization, refused to agree to proposals for establishment on its bases of subdepots under control of the Maintenance Command, and that command, in turn, refused to accept the principle that all service organizations on AFCC bases must be responsible ultimately to the Combat Command.8

The fact that Arnold as Chief of the AAF after 20 June 1941 had jurisdiction over both the Air Corps and the Air Force Combat Command provided the authority to resolve this difference of opinion. Plans soon took shape for a redesignation of the Maintenance Command as the Air Service Command, with an enlarged jurisdiction reaching into AFCC bases. General Emmons, as commander of the

* See above, pp. 18-19.

† For official definition of the several echelons, see below, pp. 384n, 388n.

--365--

AFCC, countered with recommendations which would have given the AFCC an even greater degree of logistical autonomy than it already enjoyed.9 But when on 17 October 1941 the AAF established the Air Service Command as successor to the Maintenance Command, it conceded to AFCC views only to the extent of a provision leaving primary administrative responsibilities for subdepots to the station commander. Otherwise, the chief of the ASC, Brig. Gen. Henry J. F. Miller, was charged with supervision in the United States of all AAF activities pertaining to storage and issue of supplies procured by the Air Corps and with overhaul, repair, maintenance, and salvage of all Air Corps equipment and supplies beyond the limits of the first two echelons of maintenance. The command was directed to compile AAF requirements for Air Corps and other supplies, to procure equipment and supplies needed for the operation and maintenance of AAF units, to prepare and issue all technical orders and instructions regarding Air Corps materiel, and to exercise technical control* over air depots outside of the continental limits of the United States. In addition, ASC received responsibility for coordination with the Army technical services in the supply and maintenance of equipment and supplies procured by them for the use of the AAF. The new command was separated from the Materiel Division but remained a part of the OCAC.10

Between October 1941 and March 1942 the Air Service Command remained under the jurisdiction of the Chief of the Air Corps. Immediately after the beginning of the war it moved its headquarters to Washington, where it began operations on 15 December 1941.†But a large portion of the headquarters organization remained at Wright Field, where it carried on the greater part of the command's activities.11

The elevation of the Army Air Forces on 9 March 1942 to the status of one of the three major coordinate elements of the Army opened the way to solution of other problems lingering on as a result of the earlier organization. Both the OCAC and the AFCC were dissolved and AAF Headquarters took control of the forces previously assigned to them.12 The Air Service Command now became one of the major AAF commands, with relatively clear lines of responsibility

*A loosely defined term used to indicate a right to issue instructions on technical questions relating to service activities.

† On 15 December 1942 its headquarters moved back to Dayton, establishing itself at Patterson Field, immediately adjacent to Wright Field.

--366--

and authority. Four air service area commands, successors to the maintenance wings, had been activated in December 1941 to supervise the depots in given geographical areas. The depots, of which there were eleven by April 1942, became the centers of depot control areas, which directed the activities of subdepots within defined geographical limits. Unfortunately, the boundaries of some of the depot control areas overlapped those of air service areas, and since the depots were the real focal points of supply and maintenance activities, the air service areas never attained the status of fully functioning ASC subcommands. The air service areas were disbanded on 1 February 1943, to be succeeded by air depot control area commands, which were simply the eleven former depot control areas under a new name. The elimination of the four air service areas was apparently justified by subsequent operations; according to Maj. Gen. Walter H. Frank, commander of the ASC, the step proved "most beneficial." In May 1943 the air depot control area commands were redesignated air service commands with appropriate geographical designations, and from then to the end of the war the ASC conducted its operations in the continental United States through its eleven air service commands,* each serving a separate geographical area.13

These air service commands directed the operations of a variety of installations and units of which the subdepots were the most important from the viewpoint of the combat and training units. At existing Air Corps bases in 1941 the materiel sections (engineering and supply departments) had been redesignated subdepots and cadres were trained to staff the many new bases being built; after January 1942 the Air Service Command extended the subdepot system to AFCC bases. These subdepots were charged with responsibility for third echelon maintenance of Air Corps equipment and procurement, storage, and issue of all types of Air Corps supplies, including fuel and oil. In the performance of these functions, the subdepots came directly under the control of the depots and were therefore in a chain of command headed by ASC. Despite ASC's effort during 1942 to extend its control over administrative and housekeeping functions for units assigned to the subdepots, these responsibilities remained with the base commanders.14 The total number of subdepots in operation had reached 47 by the time of Pearl Harbor and 130 by September 1942; the peak number of 238 was reached at the beginning of 1944. In general, it

* In 1944 they were redesignated air technical service commands.

--367--

was the policy to man the subdepots with civilians, the number of employees per subdepot ranging from too to 800; however, at certain isolated bases where it was found impossible to recruit civilian labor in sufficient number the ASC stationed its own service squadrons.15

On 1 January 1944, in compliance with a decision of AAF Headquarters, the Air Service Command transferred the subdepots to the control of the commands or air forces on whose bases they were stationed. The basic reason for the transfer was apparently the desire at almost all levels of the combat echelon that the flying-unit commander have control of all of the services available on the air base, and AAF Headquarters supported this stand. Certainly there had been difficulties, probably inevitable under the circumstances, between sub-depots and base commanders, and in such struggles for control of functions and units the combat echelon generally won out over the logistical one. The ASC retained responsibility for establishing engineering standards for the subdepots through publication of technical orders and instructions and for conducting quarterly inspections of the maintenance and supply activities of the subdepots. The loss of control of the third echelon supply and maintenance function on the bases left the ASC with the fourth echelon functions performed by its depots. One informed judgment held that while the transfer of the subdepots may have been desirable or necessary from the standpoint of administration of the individual air base, it may well have been undesirable for efficiency of the subdepot system as a whole.16

In addition to operating the depots and subdepots within the continental United States, the ASC was responsible for the shipment of Air Corps supplies and equipment to overseas theaters of operations. The channels of supply to overseas air forces depended chiefly upon two major ports of embarkation, New York and San Francisco, where the Transportation Corps of the Army provided the necessary port authority headed by a port commander. Because of the specialized nature of its equipment (and a constant readiness to assert its autonomy at every opportunity), the AAF found it desirable to set up special organizations for handling AAF equipment and supplies passing through the ports. During most of 1942, AAF activities at the ports were carried on by port air officers who were responsible to ASC as well as to the port commander. In November 1942 the ASC unofficially organized the New York Air Service Port Area Command which took over most of the port air officer's responsibilities,

--368--

except those pertaining to shipment of troops and their accompanying equipment.17

The growing importance of supplying the overseas air forces and the need for more efficient control of supply shipments led to the activation on 1 October 1943 of the Atlantic and the Pacific Overseas Air Service Commands, with headquarters at Newark, New Jersey, and Oakland, California, respectively. The Atlantic Overseas Air Service Command, successor to the New York Air Service Port Area Command, exercised control over the movement of Air Corps cargo through the ports of embarkation on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. The Pacific Overseas Air Service Command performed the same function on the Pacific coast. The new commands also assumed control of the huge intransit depots previously established under the regional air service commands for receipt and distribution of supplies destined for overseas shipment. In addition to planning, booking, and delivering cargo to the ports, the two commands were soon authorized to initiate action on overseas requests and to direct action on certain special supply projects.18

The service units which supported the combat groups in overseas theaters of operations constituted the final links in the organizational chain of the AAF logistical system. Although ASC did not control, except through technical instructions, the overseas operations of service and air depot groups, it was responsible for organizing and training them for assignment to the overseas air forces.

Before 1941 the combat groups of the GHQ Air Force had operated from permanent bases with fixed service installations. Although there had been discussion of the probable need for mobile service units to accompany combat units into the field in the event of war, little had been done to create such organizations. The great expansion of the air arm and the imminence of war during the months before Pearl Harbor lent real urgency to the search for units suited to the need. After considerable experimentation during 1941 and early 1942, the service group and the air depot group emerged as the two basic field logistical units. The service group had its antecedent in the air base group which since 1941 had been performing supply and maintenance functions on combat bases, but it was better organized and more mobile than its predecessor. Its function was to provide third echelon supply and maintenance for combat units in the field, and, in practice, it generally shared the same base with the unit or units it

--369--

served. The air depot group, originally organized in 1941 to provide both third and fourth echelon services, was reorganized to provide only fourth echelon supply and maintenance in overseas theaters. The air depot groups were much less mobile than the service groups because of the heavy maintenance machinery and the large stocks of supplies upon which their operations necessarily depended.19 The Air Service Command controlled the training of air depot groups from their beginnings in 1941, and assumed direction of the training of service groups in June 1942.*

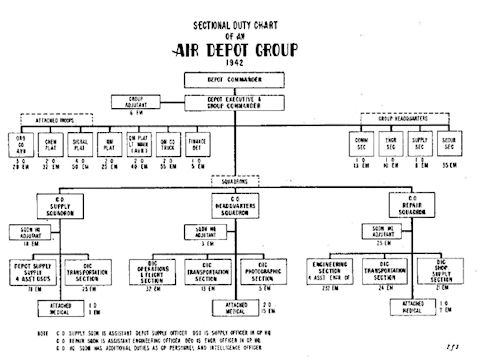

The organization of these units emphasized the dual character of the function to be performed. According to T/O's issued in the summer of 1942, the air depot group was built around a supply squadron and a repair squadron. There were, in addition, a headquarters squadron and a variety of attached personnel or units from other arms and services, among them Ordnance, Chemical Warfare, Signal, Quartermaster, Finance, and Medical. To indicate the structure of the group, a sectional duty chart taken from the Air Service Command manual of 15 July 1942 is reproduced on page 371. The service group, with a total strength of more than a thousand men, was made up of two service squadrons and attached units. Though functional divisions of assignments within the squadron lent emphasis either to supply or repair work, the squadron itself was manned and equipped for the rendering of both types of service.

Although the ASC did not have control of overseas logistical operations, it sought to prescribe the necessary organization in overseas theaters. It was assumed that each air force would have its own air service command, and AAF Regulation 65-1, issued on 14 August 1942, outlined the organization of a typical overseas air service command. Such a command would control third and fourth echelon supply and maintenance. The air depot groups under it would handle fourth echelon services, generally manning base depots in the port areas and advanced depots situated closer to the bases of combat operation. The service group usually would operate a service center in the immediate neighborhood of combat bases and was organized with a view to providing services for two combat groups. Where feasible and more efficient, the service group might be placed on the same station with the combat group or groups it served. In actual practice, most of the overseas air forces deviated considerably from

* On training, see below, pp. 667-72.

--370--

this proposed organization. Many of them did not see fit to entrust their air service commands with control of the third echelon services, particularly when, as was often the case, the service unit was stationed on the same base with the combat group. They preferred to retain unity of command on the air base, adhering to the same principle which was responsible for the Air Service Command's losing control of subdepots on continental United States bases at the beginning

of 1944. Consequently, most overseas air service commands were concerned primarily with fourth echelon services, although they generally had some form of technical control over units providing third echelon services.20

The desired mobility was attained reasonably well in the third echelon operations of the overseas tactical air forces. The strategic air forces (Eighth, Fifteenth, and Twentieth), however, did not require mobile service units because the heavy bombardment groups normally operated from fixed bases that usually remained unchanged for the duration of the war.* Fourth echelon services never attained

* The bombardment groups of the Fifteenth Air Force stayed put once they established themselves in the Foggia region in Italy in 1943-44.

--371--

the mobility that had been hoped for, and throughout the world the air depot group tended to be anchored to the same place for much longer periods than were the service groups. As the air forces in Europe and the Pacific moved forward with the ground armies, the base depots and other installations operated by the air depot groups found themselves at increasingly greater distances from the units they were supposed to serve. The movement of an air depot group generally presented a major transportation problem because of its enormous impedimenta of machinery and supplies. Efforts to make the depot groups more mobile were not particularly successful because the efficient performance of their mission required them to be heavily encumbered.21

Besides struggling with problems affecting the organization and training of service units for overseas assignment, ASC experienced difficulty in attaining a workable division of responsibilities with its parent body. In the general reorganization of March 1942 the Materiel Division had been reconstituted as the Materiel Command, with a jurisdiction incorporating the functions left to the Materiel Division after the establishment of ASC. In general, the line dividing the two commands was clear enough: Materiel Command was the principal procurement agency of the AAF, with a consequent control over research and development; ASC was charged primarily with the distribution of equipment and supplies and with the provision of maintenance services. But there were difficulties. As a new command, ASC required time to develop the degree of self-sufficiency that was necessary for independence of its parent organization.22 Moreover, a certain overlapping of function was virtually unavoidable; however logical the line of demarcation, it was difficult to make the line precise. Although the Materiel Command remained the AAF's chief procurement agency, the ASC had been given a limited authority for procurement, with some resultant confusion and disagreement. At the same time, the operation of the Defense Aid Organization, which procured, stored, issued, and transported supplies and equipment for beneficiary foreign governments, remained under the Materiel Command. The transfer of the Defense Aid Organization to ASC in May 1942 facilitated the handling of all distribution through one supply system.23 But a divided responsibility for determination of requirements continued to demand a closer coordination and agreement between the two commands than was always possible. The Materiel

--372--

Command had the initial responsibility for purchase of airplanes and the equipment originally installed in them, while the ASC had the authority for the purchase of standard organizational equipment. The possibilities for overlapping jurisdiction in this field were manifold, and the disagreements between the two commands not infrequent. On occasion the Materiel Command would develop items of equipment which ASC would refuse to order because it was not convinced of their superiority over existing models. On the other hand, the Materiel Command would control the flow of spares to the ASC by fixing production schedules which did not always meet with the latter's approval. Other areas of overlapping and conflicting jurisdiction included engineering, packaging, salvage, the preparation and dispatch of shipping instructions to manufacturers, procurement of technical information from contractors, handling of unsatisfactory reports on equipment, standardization of equipment, disposal of excess property, and conservation of materials.24

As early as the summer of 1942 suggestions were made that the two commands would have to be united, and some argued that the newly established Air Transport Command (ATC) * should be included in such a merger for the sake of a truly integrated logistical organization. Arnold himself was interested enough in March 1943 to ask for a study of the desirability of placing the three commands "under one head," but no action ensued and the idea of an AAF Services of Supply that would include all logistical agencies was dropped.25 By June 1944, however, AAF Headquarters had decided to combine the Materiel Command and the Air Service Command, a consolidation effected on 1 September 1944 with the activation of the Air Technical Service Command (ATSC) under Lt. Gen. William S. Knudsen. The actual consolidation of the two commands proceeded slowly in order to avoid severe dislocations which might impede the war effort. At AAF Headquarters the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Materiel and Services, General Echols, retained responsibility for establishing AAF materiel and supply policies and for supervising the execution of such policies.26 Thus in a period of less than three years, the organization of the AAF logistical function had come full circle--from unity to separation and back--except that the air transport responsibility remained

* The ASC had had the 50th Transport Wing for the transportation of freight and personnel. For a few months in the spring of 1942 it appeared that the ASC would be given all air transport and ferrying functions, but in June 1942 the Air Transport Command was charged with this important mission (see Vol I, 359-62).

--373--

with the ATC and the staff and command principle was more clearly established in the ATSC than it had been with the Materiel Division.

The relationship between the AAF and the ASF also had a profound effect on the development of air service organization and operations. The special position accorded the AAF within the War Department included responsibility for procurement of all equipment "peculiar to the Army Air Forces" and command of AAF stations not assigned to defense commands or theaters. The establishment of the Amy Service Forces as the over-all logistical agency of the War Department inevitably set the stage for disputes between the two commands. The powerful drive of the AAF for greater autonomy and the almost equally strong urge of the ASF for a greater degree of control of Army-wide logistics contributed much to the creation and broadening of differences which marred, but did not seriously hamper, an otherwise successful collaboration of the two commands.27

The chief differences between the AAF and the ASF centered about procurement for and administration of the AAF's bases. On policy affecting contracts, prices, and manpower, the AAF generally was willing to accept guidance from the ASF when acting in the name of the Under Secretary of War. But the AAF insisted on determining its own supply requirements and directing production of the materiel it ordered. It sought also to acquire procurement authority over a wider range of materiel, including many of the specialized items purchased for it by the technical services under the ASF. AAF proposals to take over procurement of guns and ammunition from the Ordnance Department were rejected, but success attended the AAF's attempts to relieve the Corps of Engineers and the Transportation Corps of authority for procurement of certain items of equipment. The most significant advance in procurement authority occurred in the fall of 1944 when the Chief of Staff directed that the AAF divest the Signal Corps of its responsibility for development, purchase, and storage of all communications and radar equipment used in aircraft. The procurement program thus transferred had an average value of one billion dollars per year during the war. The transfer, completed in the spring of 1945, involved some 9,000 military and civilian personnel, as well as a number of installations.28

The trend toward greater logistical autonomy was extended to the air bases, where the AAF whittled away the prerogatives originally

--374--

granted to the ASF. According to regulations adopted in 1942, the ASF had responsibility for a number of air base functions ranging from general courts-martial to operation of laundries. The AAF had refused in the summer of 1942 to permit its own Air Service Command to handle administrative and housekeeping activities on AAF bases; it was, of course, even less disposed to permit the ASF any considerable measure of control at the air base level and resisted what it regarded as encroachments. During the course of the war the AAF secured War Department approval for relieving the ASF of the supervisory responsibility for many of the functions performed on the air bases, including signal communications, ordnance maintenance, repairs and utilities, operation of laundries, salvage activities, and special services. The AAF also acquired supervisory responsibility for the establishment of stock levels of common use items* at air bases.29

The AAF also sought to secure complete control of its attached ASF units, which performed vital services for the air forces everywhere. The troops in these units, known as Arms and Services with the AAF (ASWAAF), represented almost every one of the Army administrative and technical services-Ordnance, Engineer, Signal, Quartermaster, Medical, Chemical Warfare, Chaplain, Adjutant General, Finance, Military Police. These troops averaged between 20 and 25 per cent of the total strength of the AAF during most of the war, reaching a peak of more than 600,000 in the fall of 1943. Trained by the ASF and attached to the AAF for duty, they retained their identity as members of their own arm or service. The War Department approved the integration of most of these troops into the AAF in the fall of 1943, but the actual process was so long drawn out that it had not been fully completed at the end of the war.30

Although the AAF did not completely succeed in throwing off ASF supervision of its logistical activities, it had gone a long way toward that goal by the end of the war. Confident that it was destined to become a separate military service in the postwar period, the AAF made its organizational changes and arrangements with the future in mind. These arrangements were not always compatible with maximum operational efficiency, but it would be difficult to show that they seriously interfered with the prosecution of the war. In the Air Technical Service Command the AAF had developed a solid logistical foundation on which to erect a separate air force,

* See below, p. 376.

--375--

Supply

The AAF supply system stretched from the factories in the United States to air bases in China, New Guinea, North Africa, Italy, England--to every corner of the globe where the AAF operated airplanes. The stock in trade of this system consisted of Air Corps and common use items of materiel. Air Corps supply handled items peculiar to that service-aircraft and related equipment--procured directly from the factory. Common use items were those which were in general use by all elements of the Army--food, clothing, ammunition, oil and gasoline, most communications equipment, etc. These items were procured for the AAF by the technical services of the Army and entered the AAF pipeline through Army Service Forces channels, either in the United States or overseas.

Within the United States, the Air Service Command computed the requirements for AAF materiel and, together with the Materiel Command, procured the various items. ASC storage depots received a constant stream of materiel from the factories and channeled it to operating forces at home and abroad. From storage depots, or direct from the factory, supplies were moved to control area depots and thence to subdepots for distribution to flying units on air bases in the United States; materials intended for overseas consumption moved from storage or area depots to intransit depots located near the major ports for water shipment overseas. Overseas the air service commands received the shipments for distribution to individual AAF organizations.

The initial problem in the operation of any supply system is to fix requirements. A requirement was defined in an official document late in the war, "as the quantity of a particular item or designated group of items needed for a specified military force during a stated period."31 Requirements for aircraft were determined at AAF Head-quarters in accordance with programs established at higher levels of authority, but the ASC had responsibility for determining the requirements for a myriad of other items needed by the AAF and for procuring them or requesting procurement by the Materiel Command or the ASF. In 1940 there were perhaps ten people in the Field Service Section of the Materiel Division engaged in the computation of requirements of spare parts for the Air Corps. By 1945 the work required the services of a large segment of the ATSC headquarters staff.

If measured against an ideal standard, which must be recognized as

--376--

impossible of attainment, the setting of requirements at the ASC level left much to be desired. Frequent and chronic shortages during the first two years of the war--the result partly of demands greater than had been anticipated when requirements were drawn up before the war--encouraged the responsible staffs to follow the safe, even though it might be a wasteful, policy. Money was plentiful and time was short; the natural inclination was to buy and thus to avoid the risk of further shortages. The situation during these earlier years offered, of course, much justification for the practice, and it should be noted that repeated changes in the over-all programs which formed the bases for computing subsidiary requirements made exact estimates the more difficult to achieve. But it cannot be said that the habits and attitudes shaped by the conditions of the earlier war years had been corrected by the end of the war.32 Certainly the war ended with large surpluses on hand, much larger probably than were justified.

The Air Service Command had responsibility for the maintenance of stock records and for the collection and analysis of consumption data. Because they were of fundamental significance for the operation of the whole supply system, the successful performance of these two functions was of vital concern to the ASC and, indeed, to the whole AAF. Up to 1940 the Air Corps had maintained a stock-record system which had provided sufficient information for the computation of spare parts and other requirements. In an era when procurement was measured by the needs of scores of planes instead of thousands, and when there was no complicating factor like a war to cause fluctuations in consumption rates, it was no great feat to keep accurate records of stockage and consumption. The job was burdensome because of the handful of people assigned to the work, but the scope of the problem was well within their competence. The vast expansion launched in 1940 had as profound an effect on the AAF stock-recordkeeping system as it had on almost any other AAF activity. The great increase in the number of planes, the multiplication of types and models, and the constant modifications of models eventually made it impossible for responsible agencies to keep records of sufficient accuracy or adequacy to be used extensively in the calculation of requirements. Statements of requirements for spare parts during 1942 and 1943, when the greater part of the procurement orders were placed, were based on "educated guesses" rather than on any real knowledge of consumption rates or stocks on hand.33

--377--

By 1942 the flow of supplies into the depots reached a rate beyond the capacity of existing facilities to handle it properly. Most of the depots were new or even still under construction, and their staffs were as yet inexperienced and imperfectly trained. Immediately after Pearl Harbor some depots, like that at Ogden, were inundated by massive stocks removed from coastal locations considered vulnerable to enemy attack. It proved impossible to inventory and bin such stocks because of lack of staff and storage space. Boxes and crates were dumped on the ground in the open, and no one at the depots knew the contents of the containers which covered hundreds of thousands of square feet. Consequently, these stocks were, in effect, unavailable and the ASC procured additional quantities of many items which it really had in stock but had lost track of. Not until 1943 did the ASC depots find the time for a comprehensive inventory of stocks--a task which required many months to complete.34

The number of AAF stock items mounted steadily from approximately 80,000 in 1940 to more than 500,000 in 1944. Records could not keep up with the phenomenal growth of the inventory or the rapid changes which occurred. The ASC made valiant efforts to keep stock-consumption records both by hand and by machine, but the records continued to be inaccurate or too outdated to serve as an accurate base for computation of requirements. From the overseas theaters there were virtually no valid consumption data available during 1942 and 1943, for the then fluid state of the combat areas did not permit the establishment of an effective reporting system. There was an increased flow of consumption data from overseas during 1944-45, but it was not enough to present the comprehensive picture required by ASC.35

Other deficiencies in the reporting system seriously affected the accurate calculation of requirements. The AAF possessed large quantities of repairable materiel items, but the pressures on maintenance organizations were such as to make it difficult for ASC to get accurate evidence on the prospective flow of repair work. The result was inadequate consideration of this factor in the computation of requirements and a further distortion of the over-all situation. Another major difficulty was the lack of uniformity in identifying items. This led to the stocking of identical items in many different ways under a variety of parts numbers. Contractors frequently changed the numbers of their parts at will, with the result that some parts had three or

--378--

four different numbers, some numbers were assigned to two or more different parts, and thousands of items had no identifiable parts numbers at all. Not until 1945 did the AAF make real progress toward establishing a uniform and accurate method of numbering spare parts.36

The leveling off of production and of AAF strength at approximately the same time in 1944 afforded the ASC an opportunity to refine its computation techniques. Substantial progress in this direction was made during 1944-45, and by the end of the war the ASC was on its way toward creation of procedures which promised to provide more accurate and comprehensive data for the calculation of requirements.

Although the computation of requirements was an important and vital function of the Air Service Command, its more pressing job was distribution. In peacetime the Air Corps had needed no complex machinery for the performance of this task. Acting on its own estimate of requirements, the Materiel Division ordered the needed supplies, usually in quantities covering the requirements for a period of one year, from manufacturers or other sources; deliveries were made to the four area depots, which in turn distributed the supplies to Air Corps stations. Sometimes the manufacturer shipped direct to the station and, under certain conditions, local purchase of some items was authorized.37 The system met the prewar need well enough, but it could not be expected to be adequate after 1941. Between 1939 and 1945 AAF personnel increased 100 fold, and aircraft almost 40 fold. The supply system had to keep pace with demands which grew larger by the day and eventually flowed in from all parts of the world.

Beginning in 1940, the four original depots were greatly expanded, and the total number of such area depots had been increased to eleven by the end of 1942.* Even so the addition of space failed to keep up with the need. Between January and December 1942, for example, warehouse space at the San Antonio Air Depot increased 500 per cent, but receipts had exceeded shipments by approximately one-third and still more space was required. Extraordinary measures, including the leasing of warehouses as much as sixteen miles from depots, helped to ease the problem somewhat but offered no full solution.38

* The seven new air depots were Ogden, Utah; Warner Robins (Macon), Ga.; Mobile, Ala.; Oklahoma City, Okla.; Rome, N.Y.; Spokane, Wash.; and San Bernardino, Calif. A depot was also opened at Miami, Fla., in 1943 but it never became a control area depot.

--379--

The inability of the area depots to handle the mountainous stocks of materiel which by the spring of 1942 were pouring from the factories, and the consequent piling up of airframe and engine parts in the manufacturing plants, spurred ASC to establish storage depots near the larger factories. These depots were to serve the area depots, storing large bulky supplies and issuing them as directed by the latter. By the summer of 1943 about forty storage depots were in operation; others had had a temporary existence. To obtain them, the AAF bought, built, or leased a variety of structures, the leases including a number of state fair grounds. In taking over responsibility for distribution of defense aid equipment, ASC acquired control over the operation of additional depots--twelve all told--which assembled, stored, and shipped lend-lease materiel to the ports. There were thirteen intransit depots by November 1943 for the handling of supplies en route to the overseas air forces. Government-furnished equipment (GFE) depots were established by the Materiel Command early in 1942 under the administration of its procurement districts. The eight GFE depots, which received, stored, and distributed GFE to aircraft manufacturers, were incorporated into the over-all ATSC depot system in 1944.39

. By the end of 1942 the ASC depot system, including the subdepots on the stations, used a total of more than 20,000,000 square feet of storage space. Estimated needs by 1 August 1943 were fixed at 52,000,000 square feet. By August 1944 the total had reached some 62,000,000 square feet, not counting the subdepots, which had an additional 8,000,000 square feet of space. Two-thirds of the ASC-controlled storage space was government-owned and the remainder leased. During 1944 the cutting of authorized supply levels and the decreased demands from units and stations in the United States so eased the storage problem that some of the space previously acquired could be released.40

This enormous expansion had brought with it serious administrative problems. It proved especially difficult to maintain in the area depots reserve stocks sufficiently large to guarantee prompt meeting of all demands for supply of particular items. After extended study of the problem in 1942, it was decided to establish specialized depots, each of them, as a general rule, stocking only one property class or sub-class of materiel. Thus the full stock in any class could serve as a reserve to meet promptly, on requisition from the several area depots,

--380--

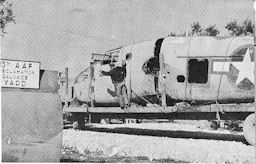

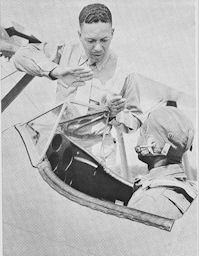

MAINTENANCE, STATESIDE |

|

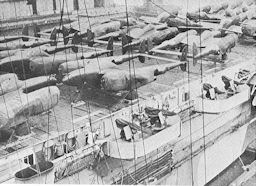

MAINTENANCE IN ETO |

|

SALVAGE |

|

SUPPLY ON GUAM |

|

OVERSEAS DELIVERY OF FIGHTERS |

|

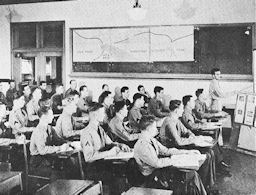

CADET GROUND SCHOOL, RANDOLPH FIELD, TEX., SPRING 1942 |

|

the demand from any quarter. By June 1943 there were forty-two specialized depots, although only thirty-six were as yet in operation; the maximum number of such depots--probably sixty-eight--was reached at the end of 1943. Consolidations and inactivations had reduced the number to fifty by mid-1944. Most of them were located near aircraft plants, and many of the storage depots had been incorporated into the new specialized system, which General Frank described as the "backbone of Supply for the AAF."41 The stocking of the specialized depots had required a tremendous readjustment of depot stocks and a consequent strain on the transportation system, but the advantage gained proved to be worth the effort.

ASC depots in August 1944 employed more than 280,000 persons,* military and civilian.42 The materiel with which they were charged fell into two major categories--organizational equipment and maintenance supplies. Organizational-equipment was that permanently issued to an organization for its use in the performance of a combat or service mission. Normally, tables of equipment prescribed for each type of unit the equipment, whether of airplanes or of tools to be provided for the mechanics' kit, necessary to the performance of its duties. Maintenance supplies included spare parts and such materials as might be required for the repair and overhaul of aircraft and other equipment.

The problems involved in the distribution of organizational equipment (other than aircraft, which are discussed elsewhere)† resulted from such causes as the unusually rapid activation of units during the earlier part of the war, shortages of various items of materiel, the lack of trained personnel at the supply depots and in the receiving units, and changes in supply tables and technical orders. The speed with which units were activated created a serious backlog of unfilled orders for organizational equipment during 1942, partly because of demand at times outrunning supply and partly because of administrative and transportation difficulties. New depots and new supply officers found it difficult to cope with the countless requests for efficient and speedy service, especially when the best efforts of the ASC reporting system failed to provide the basic data needed for efficient operation. Frequent changes in supply tables and in technical

* This figure includes a large number who at area depots performed important maintenance services. See below, p. 390.

† See below, pp. 412-23.

--381--

orders made it all the more difficult to equip units as promptly as was desired.43

There was no sovereign remedy for these problems, and ASC applied itself painfully to such revisions of policies and techniques as would improve the flow of equipment to units--especially those going overseas. The simplification of property-accounting procedures reduced the burden of paper work on the combat unit and facilitated reporting of equipment status. But the basic problem remained that of getting equipment to newly organized units which had none whatsoever. It proved impossible to make equipment available to new units at their stations of activation because they frequently, if not usually, left these stations shortly after activation. The waste of transportation involved in transshipping equipment, sometimes several times before it could catch up with the unit, led to a policy of sending initial equipment to the first training station instead of to the station of activation. This gave the depots more time to assemble and ship the equipment.44

Eventually ASC determined that it would be more efficient to issue organizational equipment to units on their arrival overseas rather than at some phase of their training careers in the United States. The advantages of such a system included el urination of the time, effort, and materials involved in packing, unpacking, and transporting equipment among a series of stations in the United States. By issuing to operational training units and operational replacement units sufficient equipment for use by organizations undergoing training, the ASC made it unnecessary for the latter to carry such equipment with them from station to station during their training cycles.* The depots acquired enough breathing space under this system to allow them to preassemble and pack for overseas shipment full sets of equipment for every major type of AAF unit. In addition, a unit freshly equipped overseas imposed fewer burdens on local services for replacement of equipment, and its equipment at the time of its commitment against the enemy was of the latest. It could also be expected that more accurate accounting would result from the new system.45

The experience of overseas commands, as well as that of ASC, encouraged the adoption of these procedures. As late as the summer

* The equipment remained permanently at the training station for use by subsequent units.

--382--

of 1943, units still were arriving at their overseas stations ahead of their equipment, or with only a part of it. Troopships usually were faster than the cargo vessels on which the equipment was loaded, and it was not always possible to follow a practice of loading the unit and its equipment together. Sometimes units in the theater had to wait several months for their equipment. Beginning in the summer of 1943, ASC shipped preassembled sets of unit equipment to the overseas theaters anywhere from thirty to sixty days ahead of scheduled troop movements. Policy on organizational equipment thus came to be based upon two principles: equipping the unit only upon arrival at its ultimate station, with preshipment in such quantity as to guarantee a prompt supply; and stocking training organizations within the U.S. sufficiently to provide borrowed equipment for all units in training. The system worked so well as to raise a question as to why it was not adopted earlier. On this point, it seems fair to conclude that the system would not have been as successful had it been instituted earlier, for before 1943 the flow of materiel from the factories was probably not great enough to permit the provision of the dual sets of equipment on which the system was based.46

Maintenance or technical supplies were the indispensable complement of organizational equipment and constituted the bulk of the total AAF materiel distributed, especially during the last year of the war, by which time most of the units had been equipped.* In spite of shortages and transportation difficulties during the early months of the war, Zone of Interior needs presented no problem that could not be handled well enough through ASC's rapidly developing depot system. But the long overseas supply lines--up to 12,000 miles--required special policies and techniques in order to insure efficient operation.47

During the first twelve to fifteen months of the war the AAF relied on a system of automatic supply for provision of technical equipment to overseas theaters. Under this system the initial shipment would be followed by a continuing flow based on anticipated rates of consumption. It was found most convenient to ship such supplies in pack-ups--cases containing enough parts or materials to maintain a given number of planes for a given number of days. Originally, the manufacturers determined the composition of these pack-ups, but their ignorance of changing needs in the field, combined with their

* The B-29 groups were the chief exception.

--383--

inclination to include items of which they had a plentiful stock rather than those which were most needed, caused ASC to assume responsibility for selection of parts. The ASC developed supply tables which were lists of the maintenance and overhaul parts (items like gaskets, landing gear, wing tips) and supplies (sheet metal, rope, solvents, etc.) required for maintenance. There were many such tables, each designed to meet the requirements for maintenance of aircraft and equipment under a variety of circumstances at the several echelons* of maintenance.48

The AAF at first directed automatic shipment of sets of supplies in accordance with the supply tables until supply overseas "reached a satisfactory level." Because of the embryonic state of supply organizations in overseas theaters and the lack of accurate consumption data based on combat experience, this was probably the most effective method available to the AAF during 1942 and into 1943. But the North African campaign provided a service test for the automatic supply system which revealed shortcomings both in the operation of the system and the composition of the tables. As a result of a conference of overseas supply officers at ASC headquarters in April 1943, the automatic supply system was abandoned in the autumn of that year. Automatic shipments of pack-ups had been neither efficient nor economical, and the inability to change the supply table quickly in accordance with experience had resulted in large excesses of many items in overseas theaters while other and more critical items were in short supply. General Arnold and others had been impressed by the huge stocks of excess supplies they found in overseas depots and felt that the situation called for a different policy.49

* AAF Regulation 65-1, 14 August 1942, gave the following definitions of the echelons of technical supply:

1) 1st Echelon: Supply facilities of the air echelon of the combat squadron. This consists of a 3-day supply level carried in the crew chief kit and is transportable by air.

2) 2d Echelon: Supply facilities of the ground echelon of the tactical squadron. This consists of a io-day supply level provided in the Squadron Engineering Set, T.O. 00-30-19.

3) 3d Echelon: Supply facilities of the service group or subdepot. In the case of the service group, this consists of a 30-day supply level.

4) 4th Echelon: Supply facilities of the Zone of Interior air depots and air depot groups. In the case of the air depot group this will normally consist of a 90- to 150-day supply level.

The above supply levels will, of course, vary with the particular situation depending upon distances involved, availability of supplies, and whether situation is static or mobile.

--384--

Supply tables, revised to bring them up to date and to render them more flexible, continued as the basis of automatic shipments for initial supply under the new policy, but all subsequent shipments were to depend upon specific requisitions from the overseas commands. Such requisitions had been employed from the first for replacement of organizational equipment and for counteracting the deficiencies of automatic supply, but now the requisition became the chief instrumentality in a system of continuing supply which left the responsibility for the determination of requirements with the using organization. Most of these requisitions were so routine that pack-ups retained their utility and normal supply took on many of the qualities of an automatic system. Special requisitions usually arose from some emergency, and their designation as "emergency requests" gave them higher priority for shipment. There were also special projects requiring shipment overseas in which the initiative came from within the Zone of Interior.50

The operation of a supply system based on requests from the users of materiel placed on overseas theaters the obligation to institute more accurate methods of stock accounting and distribution and to make stronger efforts to assemble valid consumption data. But it became increasingly clear during the latter part of 1943 that any system would result in the accumulation of excess stocks of supplies unless kept under constant surveillance. The understandable tendency at all echelons to acquire a cushion of supplies to meet all emergencies produced surpluses which sometimes amounted to as much as two years of normal supply of certain items at some of the depots. The achievement of full production by the end of 1943, with its promise of a continuing capacity for rapid replenishment of stocks, made it possible for the Army to survey the world-wide supply situation; the outcome of the survey was the so-called McNarney Directive (1 January 1944) which prescribed extensive changes in supply procedures and which established maximum stock levels for the whole Army. The stock levels set up for various classes of supply* ranged from 60 days in the European and North African theaters to as much as 180 days in China-Burma-India.51

* Army supplies were divided into five classes, of which classes I and III included such items as rations, fuels, and lubricants, consumed at an approximately uniform daily rate regardless of combat operations, while classes II, IV, and V included organizational equipment, airplanes, spares, ammunition, and supplies for which allowances were not prescribed or which required special measures of control.

--385--

The ASC made a determined effort to carry out the changes prescribed by the McNarney Directive. It reduced authorized inventories in its Zone of Interior depots to approximately a four and a half months' supply for domestic and three months' for overseas requirements from the previous six-month level for each. The reduction of stock levels in the overseas theaters proved to be much more difficult, for theater air forces still tended to build up to the maximum levels rather than reduce to the minimum consistent with effective operations. In the fall of 1944 excess stocks were apparently still the rule rather than the exception in overseas theaters. Although the ASC had been made responsible by the McNarney Directive for screening overseas requisitions in order to prevent the accumulation of surpluses, the lack of accurate and detailed information from the theaters continued to make it difficult to carry out this responsibility properly. The enormous scope of the supply system and the continued operation of factors making for frequent change--such as lengthening of supply lines, increase of aircraft and personnel strength, and special problems of transportation--made it virtually impossible to adhere strictly to any rigid theater stock levels. The ASC exercised wide discretionary powers in screening requisitions from overseas, but of necessity the theaters got the benefit of any doubt.52 To deny supplies to forces engaged in combat, even in the name of greater efficiency and economy, would have been extremely difficult even under better circumstances than existed in 1944 and 1945.

Experience during 1944-45 profusely illustrated the need for great flexibility in administering the supply system. Maintenance of prescribed stock levels in overseas theaters required establishment of timetables covering the whole supply process from receipt of the requisition by ASC to and including the theater supply level permitted. The "requisitioning objectives" table which was developed ranged from 159 days for the European theater to 334 days for the China-Burma-India theater. Close adherence to these time objectives proved to be almost impossible because the actual period for filling requisitions varied greatly from class to class and item to item of supply. Under such circumstances, maintenance of a uniform requisitioning objective or stock level for all classes of supplies was impracticable. In the Pacific theaters, for instance, operations required frequent, long-distance movements of units from island to island. The need for rapidity of movement and continuity of operations

--386--

often required that supplies for a single combat group be placed at two or three different locations in the combat area. The total supply need, therefore, was always fluctuating, exceedingly difficult to determine, and almost always in excess of prescribed theater levels. In the face of demonstrated need the ASC could not help but waive existing restrictions on supply levels.53 As a result, most of the Pacific depots were well stocked during 1945** The obvious lesson to be drawn from this experience is that the most economical supply system is not necessarily the best from the standpoint of combat operations. The ASC could only try to minimize the waste inherent in the waging of war.

For the transportation of AAF materiel overseas the ASC had to rely on other agencies, chiefly the Transportation Corps and the Air Transport Command. The great bulk of supplies went by water and, beginning in 1943, passed through the hands of the Atlantic and Pacific Overseas Air Service Commands. For the period January 1942-August 1945, AAF materiel shipped overseas by water totaled more than 19,000,000 measurement tons. More than a third of this amount went to the European theater, the scene of the AAF's most extensive operations. Between January 1943 and August 1945 the AAF shipped more than 45,500 tons of materiel overseas by air.54

The organization of supply in the overseas areas varied somewhat from theater to theater but had essentially the same characteristics. The larger theaters--European, Mediterranean, and Southwest Pacific--which had more than one air force in operation, eventually established theater air service commands in order to prevent the waste and duplication which would have resulted from competition for supply and equipment between two or more air forces. These theater air service commands received supplies from the United States, stored them in large base depots (sometimes in specialized depots), and distributed them to the individual air force service commands. Within the individual air forces there were advanced depots, usually operated by air depot groups, which kept the service units and the combat groups on the combat bases supplied with materiel. In other theaters with only a single air force, the air force service command operated the whole system.† The ASC advanced arguments

* Okinawa seems to have been an exception.

† For discussion of organization and operation of overseas supply systems, see previous volumes of this series, especially I, 628-39; II, Chaps. 18 and 19, passim; III, 126-34, Chap. 16, passim; V, Chaps. 3, 6, and 11, passim.

--387--

for extending its control of logistics to the overseas theaters, or at least as far as the ports, but did not succeed in convincing the War Department General Staff, the AAF, or the overseas commanders of the desirability of such a move.55 The Zone of Interior supply agency, therefore, had to rely on cooperation from the overseas theaters in order properly to carry out its mission. The extent to which their cooperation was possible or forthcoming often determined the degree of success attained in carrying out the mission.

Maintenance

The character and the use of the military airplane had given to maintenance services a place of fundamental importance in the peacetime Air Corps. The greatly increased rate of operations, the high incidence of battle damage, and the growing complexity of the military plane during World War II made maintenance one of the most vital functions in the waging of the air war. The quality of maintenance was often the margin of difference between the life and death of an aircrew or the success and failure of a mission.

The term "maintenance" as applied to aircraft referred to all operations necessary to keep an airplane in safe and efficient operating condition, including servicing with fuel and oil, periodic inspection, minor and major repairs, and overhaul. During the war, maintenance was divided into four echelons, distinguished from one another by the amount of work, equipment, and manpower required.*

* AAF Regulation 65-1, 14 August 1942, defined and discussed the echelons of aircraft maintenance as follows:

1) 1st Echelon: That maintenance performed by the air echelon of the combat unit.

2) 2d Echelon: That maintenance performed by the ground echelon of the combat unit, air base squadrons, and airways detachments.

3) 3d Echelon: That maintenance performed by service groups and subdepots.

4) 4th Echelon: That maintenance performed by air depots groups and air depots.

First echelon maintenance will normally consist of servicing airplanes and airplane equipment, preflight and daily inspections, and minor repairs, adjustments, and replacements. All essential tools and equipment must be transportable by air.

Second echelon maintenance will normally consist of servicing airplanes and airplane equipment, performance of the periodic preventative inspections and such adjustments, repairs, and replacements as may be accomplished by the use of hand tools and mobile equipment authorized by Tables of Basic Allowances for issue to the combat unit. This includes engine change when the organization concerned is at the location where the change is required. Most of the tools and equipment for 2d echelon can be transported by air; but certain items, such as transportation, radio, etc., necessitate ground means of transportation.

Third echelon of maintenance embraces repairs and replacements requiring mobile machinery and other equipment of such weight and bulk that ground means of transport is necessary. Units charged with this echelon of maintenance require specialized mechanics. This echelon includes field repairs and salvage, removal and replacement of major unit assemblies, fabrication of minor parts and minor repairs to aircraft structures and equipment. Normally, this echelon embraces repairs which can be completed within a limited time period, this period to be determined by the situation prevailing.

Fourth echelon of maintenance includes all operations necessary to completely restore worn or damaged aircraft to a condition of tactical serviceability and the periodic major overhaul of engines, unit assemblies, accessories, and auxiliary equipment; the fabrication of such parts as may be required in an emergency or as directed in technical instructions; the accomplishment of technical compliance changes as directed; replacement, repair, and service checking of auxiliary equipment; and the recovery, reclamation, or repair and return to service of aircraft incapable of flight.

--388--

Actually, it was impossible to draw sharp lines between the various echelons, and in time it came to be recognized that such lines were neither necessary nor desirable. Accordingly, there developed a large degree of flexibility in the operation of the maintenance system, with the availability of equipment, supplies, and manpower determining the amount and kind of work performed by a given installation or organization.

Until 1941 the Materiel Division, although its control did not extend to GHQ Air Force bases, established the policies which governed the performance of maintenance at the various echelons. It issued orders, circulars, and letters prescribing the general organization and operation of depot and station engineering departments and the methods and routines to be followed. The basic data from which policies and instructions were derived came from reports which flowed in from the depots and stations and from various inspecting activities.56

In 1939 the four Air Corps depots in the United States employed in their engineering departments a total of 1,700 civilians under the supervision of Air Corps officers. Between 1931 and 1939 these depots overhauled an average of 166 planes and 500 engines annually. The Air Corps had fewer than 2,000 aircraft, the great majority of them single-engine, of all types during most of this period. Since a considerable number of the planes were deployed in overseas departments, leaving only a portion, albeit a large one, of total Air Corps strength to be serviced by the continental depots, their capacity was adequate for all needs. In August 1939 the Air Corps actually considered reducing the number of its maintenance employees,

--389--

and Arnold admonished his staff to economize in the depots. This was at a time when the Air Corps had already embarked on its 5,500-airplane program and when war in Europe was imminent. Fortunately, as these circumstances soon made it clearly undesirable to take such a step, the depots retained the nuclei of skilled technicians who later contributed much to the expansion of the AAF maintenance system.57

The pace of AAF expansion after the summer of 1940 was so rapid that the maintenance services found it almost impossible to meet the steadily growing demands made upon them. The establishment of the Maintenance Command in 1941 was, at least in part, the result of the urgent need for more and better maintenance. Leaders at AAF Headquarters spoke out frequently and strongly during 1941 and thereafter about the shortcomings of maintenance, but they neglected to assume that part of the responsibility which was properly chargeable to them. The strong emphasis on the acquisition of aircraft had tended to subordinate problems of supply and maintenance, and these problems received inadequate attention at the top levels of the AAF until they became acute enough to obtrude themselves on the "top brass."58 The decision in 1939-already noted* --to put almost all of the funds made available to the Air Corps into complete aircraft explains in large part the critical shortage of spare parts which persisted through 1942. Hardly less significant was the failure to undertake expansion of the four original depots until late in 1940, months after over-all expansion plans had been drawn. Still another factor affecting the quality of maintenance in the earlier months of the war was the lack of adequately trained engineering officers and civilian mechanics to man the depots and subdepots. In part this lack may be attributed to the acute pressure of demand on the available supply, but in part it seems also to have resulted from a policy which gave the Air Service Command perhaps the lowest priority on officer and enlisted personnel.59

In the face of handicaps which were not of its own making, the AAF maintenance system grew rapidly during 1941 and prodigiously after Pearl Harbor. In late 1943 the eleven depots employed 65,000 people in their engineering departments, almost forty times as many as those employed in 1939. In addition, the facilities of seven-teen airlines and twenty-two other civilian concerns were brought

* Sec above, pp. 347-48.

--390--

into service on a contract basis to supplement the work done in the AAF depots. These contractors worked chiefly on training and transport planes, while the depots reserved their facilities for the more complex combat types. As the training program declined during 1944, the commercial contractors were eliminated except that the airlines continued to overhaul ATC planes until the end of the war.60 The extension of ASC control of maintenance to the subdepots on the air bases early in 1942 provided the unity which ASC considered so important to the accomplishment of its mission. In 1944, when the subdepots reverted to the control of the air forces and commands on whose bases they were stationed, the maintenance system had attained sufficient maturity to overcome most of the disadvantages which resulted from a split control of the function.61

Although the jurisdiction of ASC did not extend overseas, it was responsible for providing service units, equipment, and supplies for all AAF commands. In addition, it served as the clearinghouse for technical information and issued technical instructions for guidance of all service organizations. During 1941 and early 1942 it had been assumed that overseas maintenance organizations would be highly mobile and that they would rely on Zone of Interior establishments for the provision of some, if not many, fourth echelon services.62 Actually, most theaters established depots which with time performed almost as wide a variety of maintenance services as did the depots in the United States. The existence of these large base depots introduced a high degree of flexibility into theater maintenance, relieving the air depot groups at advanced depots and the service groups on the air bases of a wide variety of tasks which might have rendered them less mobile and permitting them to concentrate on the important task of repairing battle damage. The European theater, with its huge base depots at Burtonwood and Warton in England and its service teams operating with the Ninth Air Force in western Europe during 1944 and 1945, probably affords the best example of the fixed service installation and the mobile service unit.* Of special importance to the latter type of organization was the mobile repair shop, a van equipped with necessary tools and machinery which rendered yeoman service in North Africa and Europe between 1943 and 1945.63 The Pacific equivalent of the mobile repair shop was the floating depot-a Liberty ship converted into a supply and maintenance

* See Vol. III, 126-34 and Chap. 16, passim.

--391--

facility, complete with machine shops. During the final year of the war a number of these vessels were used, lending important assistance in the Marianas until land-based depots could be established.64

As with supplies, successful maintenance depended greatly on a two-way flow of information between the field establishments and ASC headquarters. The primary source of information about specific technical difficulties was the Unsatisfactory Report (UR). Flying units submitted UR's on defective equipment, procedures, and forms to the ASC, which either advised appropriate remedial action or arranged for necessary research on the problem. The huge growth of the AAF and the introduction of myriad items of new equipment produced a tremendous increase in the number of UR's submitted. From a total of 10,480 in 1941 UR's increased to 169,521 in 1944 and 164,155 for the first eight months of 1945. Because it became impossible to answer each UR individually, and in order to attain the widest dissemination of information as to possible remedies, the ASC began in February 1944 to issue a semimonthly Unsatisfactory Report Digest which listed specific failures, cited the number of reports received on each failure, and suggested remedial actions.65 Important information came also from technical inspectors who were to be found at all echelons of the AAF down to the base level. Their inspection reports proved to be of great value in correcting deficiencies of a broader nature than those which appeared in the UR's. Special conferences on maintenance problems at ASC headquarters and in the field contributed additional information of value in the formulation of over-all policy. General reports distributed by ASC served to bring to interested agencies helpful suggestions based upon a common experience with maintenance problems.66

On the line, the key to successful maintenance was provided by regular inspections of aircraft and engines for detection of wear or failure and for determination of such adjustments and special servicing as might be required. Of critical importance were the standards for determining when airplanes and/or engines should be sent to the depot for overhaul. By strict adherence to the best standards of inspection and routine maintenance, it was possible to lengthen the time interval between overhauls and thus to increase the force available for operation. Something of the success with which the maintenance function was performed is suggested by the fact that normal

--392--

time intervals between overhauls for both aircraft and engines increased greatly during the war. The suggested inter-overhaul time for the B-17 increased from 4,000 flying hours or 30 to 60 months of service in 1940 to 8,000 flying hours or 84 months of service in 1944. Inter-overhaul times for engines were shorter, for their intricate mechanisms were more susceptible to wear and breakdown, Even so, the time between engine overhauls also increased during the war. The time for the R-1820 series, for example, increased from 300-375 hours in 1939 to 500-650 hours in 1945.67 There were other causes for this development--among them, improvements of design and in materials--but policies encouraging such a lengthening of the intervals could be justified only on the assurance that the job of routine maintenance was being well done.