Issued by the The Belgian Campaign in Ethiopia

A trek of 2,500 miles through jungle swamps and desert wastes

byGeorge Weller

BELGIAN INFORMATION CENTER

630 Fifth Avenue, New York

Belgian National Flag, bearing the name of Tobora, a town captured by Belgian troops

in the African campaign of 1914-18.I. In jungle and mountains

BLITZED at close quarters in Europe, Belgium has crossed the entire continent of Africa to take revenge on the Axis. In a tropical campaign whose like for continuous and varied hardship has not yet been witnessed in this war, Belgium has bested Italy in Ethiopia.

Starting as a nucleus with the Force Publique, the equivalent of the American state constabulary, Belgium has taken her black police force of the Congo and hewn it into a modern army.

To strike at Germany's partner, that army with another army of patient porters to bear food and munitions up Ethiopia's dizzy mountain trails, has traveled from the damp groves of the Congo jungles, homeland of gorillas and pigmies, across the watershed lying between the Congo and the Nile, down the other side into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan along the waters of the White Nile and, finally, across the salty wastes of western Sudan to the mighty rampart of mountains guarding inner Ethiopia.

The two Niles

To attain the Italian stronghold, the Belgians had to surmount heavy tolls of dysenteric and pulmonary diseases. In face of an Italian army superior in numbers, fire power, strategic positions and not inferior in personal bravery, the Belgians have seized for the British--with whose campaign their own was co-ordinated--the natural mountain fortress.

Britain's ascendancy in Egypt depends on her maintaining control of the two Nile watersheds which remained insecure as long as Italy was master of the Ethiopian mountains. The

--2--

Colonial troops leaving for EthiopiaBritish, now besieging the last Italian forces near Gondar, aim to recover control of the Blue Nile's Ethiopian headwaters in Lake Tana.

Thanks to tiny Belgium's daring expedition, England no longer needs to worry about the White Nile's headwaters, the other source of Lower Egypt's indispensable annual supply of fertile topsoil and life-giving water. Congolese troops under the direction of Maj. Gen. Auguste Gilliaert, Belgium's solidly built, six-foot general, and commanded by Lt.-0Col. Leopold Dronkers Martens, have delivered to Britain the watershed, with a corresponding effect on London's bargaining power with regard to Egyptian government.

Nine Generals asked peace

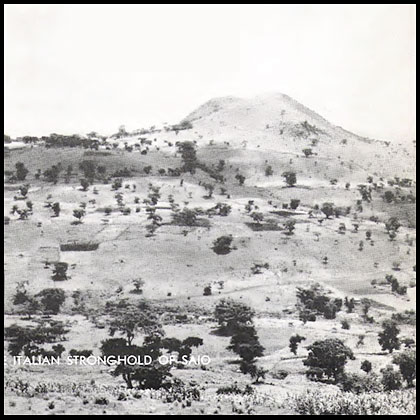

The Italian Army under Gen. Pietro Gazzera had its headquarters in this mountain town of Saio. Saio is up 5,621 feet and command a matchless view of the mountains in the direction of Addis Ababa as well as of the broiling Sudanese swampland which the Belgians conquered before assaulting the chain of Italian garrisons directed by Gen. Gazzera.

An idea of the magnitude of the forces met by Belgium's hand-made army may be derived from the fact that Gen. Gilliaert's two lieutenant-colonels and three majors, heading three battalions of colonial troops,l received overtures of peace from nine Italian generals and 370 ranking officers. To these were added 15,000 Ethiopians, headed by Eritrean non-commissioned officers.

In every one of the bitter engagements culminating in the siege of Saio. the Belgians were outnumbered three and four to one. For periods of a long as

--3--

two months, due to the impassable roads and ebb conditions on the tributaries of the White Nile, the Congolese troops were cut off from supplies. Their condition was continuously more precarious than that of their antagonists.

Weather traps U.S. trucks

How formidable natural barriers here can be is illustrated by a cavalcade of American-manufactured Belgian trucks, bearing prisoners to Addis Ababa, which is toady trapped by weather conditions in the mountains and will not be able to return until the dry season turns mud into dust. The Italian-built network of smooth autostrade ends more than 300 miles from the Province of Galla Sidamo.

Risks of taking the Congolese defense force upon a trans-African expedition several times as long as any similar caravan ever had attempted, and through virtually uninhabited country, were closely studied and warmly discussed before hand. Gov.-Gen. Pierre Ryckmans and Lt.-Gen. Paul Ermens, commander-in-chief, took part in the discussions with the South African and British military missions in Léopoldville.

Act at opportune moment

Suggestions a year ago that Italy should be attacked were considered premature. The Congolese army, organized chiefly as a colonial constabulary, was considered to have defense obligations of greater importance as long as Germany's intentions toward Portuguese Angola, and Congo's neighbor to the south, and the extent of Vichy influence in French Equatorial Africa, the Congo's neighbor to the north, remained undefined.

When the de Gaullist putsches in the Moyen Congo, Gabon, Ubangi-Shari colonies and the Chad territory (all in French Equatorial Africa) ended the uncertainy on the northern frontier, and Germany's drive into the Balkans made the possibility of her seizing Portugal more remote, the Congo's war staff and the refugee cabinet in London judged the moment opportune.

--4--

Coastal defenses of Belgian CongoMussolini's forces had deeply indented the British in Kenya and there was the possibility that they might attempt to seize Sudanese air bases along the White Nile, severing Africa horizontally and preventing American arms from reaching the Middle East.

Italian bombing planes had begun using Belgian fields in Europe for take-offs against England and a Belgian steamer had been sunk by an Italian submarine. Gov.-Gen. Ryckmans' proclamation on November 25, that a state of war existed between Italy and the Congo, was the signal for launching the counter-invasion of Ethiopia which developed rapidly after the Sudan frontier was crossed on February 2.

A dangerous maneuver

The heroic progress of the trans-African campaign has been curtained in secrecy not only for military reasons but because, from the time the campaign opened, Congolese troops were inaccessible. Foreign correspondents following the South African army's progress around Asmara, Eritrea, or northward from Mogadiscio, Italian Somaliland, were separated from the Belgians by the Italian lines.

2. A sick army beats disease to win a battle

BEFORE reaching the Ethiopian rampart held by Italian troops, Belgian colonials form the Congo had to hold together an armed column of trucks carrying soldiers, porters and munitions 1,400 miles across almost uninhabitable country. The first aim of the attack was Asosa in the region drained by the Blue Nile, about 300 miles north of the Italian headquarters at Saio.

Starting from Watsa, in northeastern Congo, the first battalion to depart climbed slowly out of the Congo watershed, whose crest is marked by the Congo-Sudanese frontier, and

--5--

descended by way of Yei to Juba, head of navigation of the White Nile. En route the troops pitched camp in the region where the aging Theodore Roosevelt came before the great war for his last shooting expedition; where the scarce white rhinoceros still hides and giraffes and elephants abount.

At Juga, with the burning bowl of the Sudanese plain before them, the column turned northward along the White Nile, then still in the dry season. River boats, with the current favorable, brought them in five days to Malakal where dwell the strange,long-legged Shilluk people, a cattle-keeping tribe of extremely thin physique who wear tan, knee-length tunics. When the clothespole Shilluks first saw the sons of Congo cannibals, with their sharpened teeth and tattoo-corrugated faces, it was difficult to say which were the more surprised.

Belgians push to aid British

Asosa, also called Bari Cossa, is located in a depression surrounded by hills and possesses barracks, a radio sttaion, a hopsital and an airdrome. It required three days for the battalion, with sweating porters carrying machine guns upon their heads, to mount from Kurmuk, Sudanese broder town, to positionsn outside Asosa, which is over 5,000 feet in altitude.

The combined attack of the Congolese trops and the King's African Rifles began on March 11, just six weeks after the Belgians left the Congo. The Italians were too completely taken by surprise to meet the combined thrusts. They abandoned Asosa, pushing southward to

--6--

Colonial troops embarking for the Sudanjoin their next garrison along the Ethiopian massif at Ghidami, 120 miles distant.

The Belgian losses were chiefly through bacillic dysentery, whose mortality is 30 per cent, and amoebic dysentery, whose death rate is 5 per cent. Sudden changes of climate worked devastatingly upon the Congolese porters, who also suffered from pulmonary diseases caused by exposure aboard the double-decker Nile barges. Accustomed to the warm, damp nights of the humid Congo basin, they caught bronchitis and pneumonia due to climate changes in the parched and grassy Sudanese lowland, where days were hot and windless and night chilly and breezy.

Pattern of strategy is set

Asosa's fall set the pattern for the eventual Allied campaign in western Ethiopia, whereby the British thrust against the headwaters of the Blue Nile became part of a general conflux of forces form Kenya to the Red Sea, all tending to thrust toward Addis Ababa and leave the Sudanese doorway held by the Belgians as the only available Italian refuge and stronghold.

In the broad conception which Gen. Sir Archibald P. Wavell, then chief of the British Middle East Command, had of the campaign, the Belgian were the anvil and assorted Scot, South African, Gold Coast, Nigerian and Ethiopian "patriotic" troops were the hammers. The central system of autostrade centering around Addis Ababa eventually began to work like a

Loading trucks in a Sudanese port for shipment to the Ethiopian front

--7--

Map of the Ethiopian Expedition

NEW SAGA OUT OF DEEPEST AFRICA has been written by a tiny Belgian force which traveled 2,500 miles across the continent to attack the Italians in Ethiopia from the west. Transported by twelve 10-ton barges and a 33-foot baby tug, the troops started from Stanley Pool just above Léopoldville and went 1,000 miles of the Congo through jungle swamps to the narrow gauge railroad which starts at Aketi. From Aketi, the midget navy rode on flatcars 450 miles to the railhead at Mungbere. Thence it motored 400 miles to Juba on the White Nile, where it where it was relaunched.

The rest of the journey across the Sudan's wastes was by the turbulent waters of the White Nile and its tributaries to the foothills of Ethiopia, where Italian strongholds were stormed.

--8--

funnel, dumping fleeing Italian officers and Eritrean subalterns down a chute which fed eastward and southeastward into the Nilobic valleys of the Baro and Sobat rivers.

Camouflaging a truck in EthiopiaAt Asosa, the Belgians discovered porters who receive wages of 1 franc (about 2½ cents), the same amount that second-class infantrymen would have spent on sandals from the Congo. The terrific heat of the Ethiopian paths had burned their bear, calloused feet nearly to the bone.

Asosa finished with virtually no losses except by disease. The battalion was given the far harder task of doubling back across the Sudanese desert to the Nile port of Melut, a distance of about 225 miles, ascending the river to the point where it meets the Sobat at Malakal, then doubling back eastward again parallel to the Sobat and Baro rivers, 275 miles to the Ethiopian foothills to close the open mouth of the bag. The Italians had already killed the single Englishman guarding the Sudanese highway frontier post in this utterly lonely land of yellowed grass and mosquito-infested swamp.

Italian raid on Sudan feared

There was the growing danger in this period of the campaign, when the Italians were still strong and well organized, that the withdrawal into western Ethiopia, which in general was orderly, might abruptly turn into a dangerous attack upon British

--9--

positions in the Sudan. At almost all points, the Italians were better armed and more amply provisioned than any Allied troops.

Had they been able to repeat the Belgian maneuver in the reverse direction and cross the burning Sudanese plains to the big airdrome beside the Nile at Malakal, there was the prospect that the British might have to withdraw troops from the Libyan front, where the Germans were making themselves sharply felt, in order to hold the Sudanese rear.

Everything depended upon a single Belgian battalion moving fast and intact around three sides of a Sudanese desert square bounded on the east by the White Nile, on the west by Ethiopia, and advancing still further eastward along the torrid road to Gambela in time to prevent Italian Gen. Pietro Gazzera, now alarmed by the fate of Asosa, from striking first along the same road into the Sudan.

The battalion, composed of 700 men and about 400 porters, made the 800-mile journey through country where the temperature ranged constantly above 100 degrees, in 11 days. This meant 11 days of the severest hardship for men alternately buffeted brutally in trucks, then forced to descend to heave them from the sand.

Throughout the journey, the Belgian commanders knew that the battalion could not hope to enter the first habitable place, Gambela, at the foot of the Ethiopian mountain rampart below Saio, with fighting for a foothold. Lacking air protection of any kind, they were completely exposed to reconnoitering Italian planes.

Duce's legions halt British

The King's African Rifles, who had elected to try to force the Italians southward from Asosa toward Ghidami, along 120 miles of ravines of Italian highland, were in the meantime halted by Gen. Gazzera. It was unmistakable to the Belgians that the Italians were planning, if not to strike at the Sudan immediately, to summon all their energies for a bitter defense of Saio's natural fortress and agriculturally rich neighboring plateau.

Besides having ample munitions, an excellent system of trenches and artillery emplacements and a first-hand knowledge of the country, the Italians had selected in the Saio base one of the few areas in Ethiopia capable of supporting a colonial army living upon the land.

Although the harsh Sudanese swamp lies below Ethiopia's high back doorstep, the mountains themselves are comparable only to Switzerland for green fertility. Here is the same rich reddish soil which, passing down the Baro and Sobat rivers into the White Nile, helps furnish lower Egypt every floodtime with virginal top soil.

Native Gallas, although despised by Ethiopia's ruling Amharites became they are second-

--10--

Sudanese village on the plainsrate warriors, are excellent farmers and cattlemen, and from the writer's window standing corn rivaling Iowa's can be seen in dozens of upland pastures. Galla Sidamo is the storehouse of western Ethiopia. It was in the pantry of Saio, whose door in Gambela at the mountain's feet, that the Italians, pressed by the vanguard of Belgian forces, gathered to combine defense with the Duke of Aosta's resistance in the central plateau.

3. First assault after African trek

GAMBELA, marking the head of navigation upon the tributaries of the White Nile, lies where the Sobat River emerges from the Ethiopian mountains into the Sudanese plain, about 40 miles and 4,000 feet below the Italians' headquarters at Saio. Today its duty little square beside the 200-foot-wide river is lined with Italian motor vehicles, fast little Fiat campaign cars beside seven-ton Lancia trucks.

On the Lancias are painted designations like "Gruppo Motorizzata di Harar" ("Motorized Unit of Harar"), showing the distance that the Italians had retreated across Ethiopia when striving for a final punch against the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The single battalion of Belgians forestalled the blow.

Keep 80 Italian drivers

Belgian subalterns, some with experience at Narvik in the French Foreign Legion, sleep on cots in these Italian trucks, like American long-haul drivers. By day they watch 80 Italian drivers temporarily saved from the British prison camp at Jubdo because they alone know the secret of the Lancia's eight changes of gearshift.

The Italian chauffeurs are thankful that their knowledge has save them from crossing Ethiopia as prisoners of the Ethiopian guerrilla patriots, whose notion of squaring old accounts is mutilation.

They are being paid wages plus living expenses, in accordance with international law and appear happy that their war is over.

Defended the town bitterly

The Italians defended Gambela bitterly. They knew that if they lost the village they would be forced to retreat up into the mountain stronghold of Saio, where Gen. Pietro Gazzera, Mussolini's former war minister, had established his headquarters.

Furthermore, an Italian offensive against the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan had been planned, for possession of a chain of airdromes along the White Nile and aiming at cutting off of the West African sources of American supplies.

--11--

It this drive had been launched by Gen. Gazzera, Gambela was the only point whence either a motorized or river expedition could start. As long as Gen. Gazzera held Gambela, he knew he might be able to take the offensive. But if the Belgians were able to win Gambela, the Italian position would become defensive only, and the Fascists would be walled inside Ethiopia.

A little British spot

Gambela is barely large enough to support its country store, full of tin pans and cheap candy beads, operated by an Ethiopian Greek.

However, several one-story barracks and a radio station near the Baro River show that England has understood Gambela's political importance. Here, many miles inside the Ethiopian frontier, the British flag floats overhead. The Sudanese policemen--recruited form the tall, cranelike Shilluk people--defend this tiny British possession.

--12--

Liaison plane in an Ethiopian airportThe British had obtained from Haile Selassie a territorial concession here only the size of an American city block. This outpost of empire serves as an excellent listening post for politics along the Ethiopian watershed and is legally as British as Hyde Park. Curiously, the Italians had allowed Maj. John Morris, who has been with the Gambela concession for 16 years, to remain with the garrison of Sudanese constabulary.

Maj. Morris is a tall, blonde Briton in his late 50's. He spent several rough and tumble years in the western United States before American became too tame for his taste. His friendship with the Duke of Aosta in prewar years was rewarded when Aosta, then Italy's viceroy, sent a private message to "Little England" in Gambela warning that a declaration of war by Mussolini was impending. This enabled Maj. Morris to escape to Nasir in the Sudan, Aosta, now a British prisoner, also gave orders that the Gambela territory should be respected regardless of the war situation.

Three months after the Belgians gained Gambela, Aosta was himself a prisoner in the same Sudanese resthouse at Malakal where Maj. Morris proceeded for refuge after receiving Aosta's warning. When Maj. Morris returned to Gambela, he found everything intact.

The attack on Gambela

To storm Gambela, the Belgians, fatigued by their 800-mile, 11-day journey from Asosa, had to make a frontal attack on the village. The Italians had placed machine guns under sycamore trees along the river, making an attack by water impossible.

A second line of eight machine guns covered the road from the Sudanese desert as far as the "Sugarloaf," a 300-foot, conical hill. The flanks of the peak were ringed by Italian machine guns.

The Belgians sent Congo infantrymen creeping through the brush, led by a white officer. They silenced the machine guns on the river and then prepared to handle Sugarloaf.

"Meat-Meats' alarm foe

The Italians had called the Belgians' Congo tribesmen, "Niam-Niams." "Niam" means

--13--

meat, and a "Meat-Meat" is a black so meat-hungry that he is a cannibal. Although he used Gallas and Amharites officered by Eritreans, Gen. Gazzera called the Belgians' use of "Niam-Niams" barbarous.

Aware of the Italians' worries about the Congo appetites, the Congolese asked to charge the sides of Sugarloaf with bayonets. They wiped out the machine-gun nests.

The Belgians lost three infantrymen killed, plus three white officers and 15 Congolese wounded. The Belgian losses increased the next day, when two Caproni bombers destroyed several buildings.

The Italians refused to tell their casualties, but numerous Italian bodies were found unburied in the streets here.

Belgians hold against foe

After the Belgian battalion took Gambela, the Italians retreated by mountain road 4,000 feet to Saio, in orderly retirement, well defended.

Belgian officers here pay tribute to the fighting qualities of the younger Italian officers and particularly the Askari subalterns from Eritrea.

Exhausted and suffering almost to a man from dysentery, the Belgian battalion settled down to hold Gambela against the Italians behind and above them. The Belgians were alone between the hostile Ethiopian rampart and the Sudanese plain, without either artillery or aircraft.

However, the African radio brought the news that another battalion was en route across the Sudanese plain and a third battalion was assembling at Faradje, in northeastern Congo, preparing to dare the same journey across Africa.

4. Belgians fight for a mountain

THIS chain of mountains, source of the White Nile's waters and lower Egypt's life-renewing soil, is criss-crossed by ravines. Here, although Belgium's battle against Italy is over, death still lurks.

--14--

Truck parking field at Malakal--Belgian troop base in EthiopiaEverywhere along the steep road up to the Italian headquarters at Saio, signs protrude in the eight-foot elephant grass: "Warning! Land mine!"

The Italians, although ill-starred upon the battlefield, are probably the world's best experts at making pursuit dangerous. They not only mine the roads, but they set sensitive traps in the tall grass; some so close that if two cars meet along a one-way mountain road, whichever turns outward has an excellent chance of being blown up.

Lt.-Col. Edmond Van der Meersch, crossing Gambela's airport the other day in an American field car, saw through the windshield the forepart of the chassis jump skyward. Luckily, he and his native chauffeur escape the explosion without a scratch. The car's only damage was a blown tire.

Belgians creep up mountain

Despite the mines, the Belgians, after taking Gambela, key port of the Ethiopian headquarters of the White Nile and gateway to the Sudan, started up the 40-mile road toward Saio, 4,000 feet above them.

The columns of reddish rock rising from the grass offered an ideal situation for guerrilla warfare. But the Italian general, Pietro Gazzera, waited to make his first resistance atop the plateau. There a violent torrent called the Bortai, crossing the road at a right angle, was the first natural division between the Italians on the heights and the Belgians in the bullet-swept ravines.

--15--

The Belgians, strengthened by a company of Stokes 80 mm. mortars and a battalion under Maj. Isidore Herbeit, moved into the attack, led by Lt.-Col. Van der Meersch, who, because of his exceptional height is called "Kasongo Mulefu," -- "awfully tall."

Their forces, totaling about 1,500 men and 600 porters, were insufficient to seize the heights. The Italians were reinforced from Gore, Bure and Himma until they had 7,000 men. The Italians became so bold that the Belgians had to take the offensive to conceal the small number of their forces.

Italians kill two officers

In the first battle of the Bortai, April 15, the Belgians lost two valuable officers. Lt. Simonet, scouting alone between the lines, stumbled into an Italian ambush and was killed.

Sgt. Dorgeo, a former Foreign Legionnaire, who had arrived in the Congo after escaping from Narvik, was unfamiliar with his surroundings. He was surprised by three Italian officers who emerged from the brush holding up their hands and shouting: "We're English."

Not sure that the King's African Rifles, supposedly at Ghidami, 50 miles to the,north, might not have sent a liaison party to the Bortai, the Belgian officer lowered his revolver. He was mowed down by Italian snipers in the bush. In the ensuing fight, the Belgians lost a native corporal and four soldiers. But three Italians were killed and 40 Eritreans were killed and 70 wounded.

During the first struggles at the Bortai, the Belgians learned to respect the Italian spotting system. The Italians posted an observer in a tree with a sniper. A squad of infantrymen hid around the tree as a guard.

But the artillery barrages following the Italian observations were often wastefully long. Usually the Italians continued pounding with 77's more than an hour after the Belgian patrols had stolen back to their own lines.

The Italians took full advantage of their superior positions and armament nine days later. After a two-hour barrage, they attacked. It was the first time men from the Congo had heard the terrible concert of modern gunfire in full chorus.

Using machine guns, automatic rifles, baby machine guns and hand grenades, squads of Eritreans with Galla snipers filtered through the Belgian left and right.

--16--

Belgian trucks on rough Ethiopian terrainOne of the heroes of the unequal struggle was a porter who rushed unarmed into the gunfire to aid two radio operators. He rescued their apparatus intact. Belgian officers often were saved by their men.

The Belgians were forced to withdraw beyond a pair of hills that screened them from view. Lt.-Col. Van der Meersch's battalion bore the brunt of this battle.

Belgian rations dwindle

Following the two battles at the Bortai, the Belgian situation in the rear became critical because of weather conditions and a break in the slender line of trans-Sudanese communications.

From May 1 until June 15 is the end of the dry and the beginning of the rainy season. During these six weeks, the single road across the Sudanese plain turns into mud. The water levels of the rivers Sobat and Baro, flowing into the White Nile, are insufficient for Nile barges.

While the Italian troops ate plentifully on their highland gardens, the Belgian between Bortai brook and Gambela were on half rations. The heat mounted to 11 degrees in the shade. Clouds of mosquitoes rose from the plain.

The Gambela airdrome, whose single hangar still bears the ironical words, "Roma Doma"--"Rome is Master"--was too small for food-carrying planes. Small amounts could be dropped from the skies, but it was impossible to feed 2,500 men in this way.

Lt.-Col. Leopold Dronkers Martens, a small man known for his exceptional ability to absorb tropical heat, was hard-tested to hold the situation together.

Engineers trapped by rain

The Belgian hospital motorcade and a company of engineers were trapped by rains in the swamps between Gambela and the White Nile port of Malakal. They remained there nearly two months, and were fed exclusively by planes.

Several porters obliged to carry food to the front lines, 40 miles away on a cold rainy

--17--

plateau, died from undernourishment and fatigue. The officers, living on canned beef and rice, were also affected.

Beriberi broke out, and even today the writer finds cases still being treated at Gambela. The food supply fell so low that the officers took the camouflage nets covering the trucks and seined the river for fish.

The month of May, when no fighting took place, was the most difficult and tragic for the Belgian Force Publique.

5. Surprise move traps Italians

TRAPPED by rains rendering both the river and the road to the Sudan im passable, the trans-African expedition was in a precarious situation until the rise in the level of the Rivers Sobat and Baro, during early June, enabled reinforcements coming from the Congo via the White Nile to reach them.

The Belgians' first plan was to cut off Gen. Pietro Gazzera's army, strongly encamped in this mountain town of Saio, from Mogi, another town upon the uneven, 5,500-foot plateau. The Italian porters were bringing the principal fresh foodstuffs for the Saio garrison, numbering about 8,000 men against the Belgians' 2,000, from Mogi, which is the truck garden center of the thickly ravined highland.

To hold simultaneously the Bortai Brook front, atop the plateau facing Mogi, the Belgians were able to spare only a company and a half from their own two battalions--that is, about 250 men. It was necessary for these Belgians to descend from the plateau again and launch

--18--

Trucks taken from the Italians after the siege of Saioan attack from Gambela, the fever-infested port where the Congolese themselves had been isolated for the past six weeks.

A two-day climb

From Gambela, it was a two-day climb upon all fours by mountain goat path to the Mogi positions. It required another day for each porter to descend. The maximum burden the most courages black bearers from the Congolese jungle could carry upon their heads under such conditions was 35 pounds each. Nine of this was food eaten by themselves en route.

The bearers' legs were cut by the razor-sharp elephant grass, their bodies weakened by dysentery and malnutrition. Porters with strange Congolese names like Katanobo, Bungamuizi, Kabome and Sawila are still being cited in orders of the day for bravery and endurance as their valor finds expression in the officers' reports.

The hope of the expedition to cut the lines from Mogi was that the King's African Rifles and the British East African Regiment, blocked further north in an attempt to take Ghidami, might be able to press south and join forces with the Belgians. The Mogi siege was even more expensive in soldiers than porters.

The Belgians under Capt.-Commandant Pierre Bounameau attacked Mogi on June 9, shortly after taking Gambela. Their position in the rear was covered by the arrival by river from the Congo of another battalion under Maj. Antoine Duperoux.

Ambush food road

The Italian garrison, numbering about 300, held their well fortified position stoutly. Perceiving that Mogi could be taken only at heavy cost, the Belgians dug in around the town and sent patrols to ambush the road to Saio along which Italian food was being carried.

Lt.-Col. Leopold Dronkers Martens gave orders that the Belgians should increase their patrol activities upon the Saio Plateau to make the Italians believe that they were facing superior forces. Elephant grass, which the Italians had burned in April in order to have a sweeping line of fire, had no grown high again.

The Belgians used a ruse familiar to American pioneers in fighting the Indians.

--19--

Artillery captured from the Italians after the conquest of SaioFrequently the moved their cannon and machine guns, even before the Italians' artillery found their range, in order to give the impression of multiple points of fire. Meantime, the alarmed Gen. Gazzera tripled the Mogi garrison, bringing it to 9,000 men.

As the Belgians grew bolder, the Italians grew more discreet. The South African Air Force began to send daily patrols of three Fairey-Hartebeest biplanes which bombed Saio and machine-gunned the roads.

Them Maj. Gen. Auguste Gilliaert arrived from the Congo. Known to his men as "Kopi," meaning leopard, he is a big quiet and catlike man.

Concentrate on Saio

It was decided that the plan for taking Mogi should be dropped and the meager forces entirely concentrated upon Gen. Gazzera's headquarters at Saio.

While preparing for a broad-scale attack across Bortai Brook, Gen. Gilliaert, with Col. Martens, was several times under fire in the front lines. An Italian machine-gun officer, when told that his fire had almost wiped out the Belgian general staff, expressed astonishment that the Congolese commanders should be in the front-line trenches.

"With us nobody above the grade of captain comes that far up," he said.

While preparing a master plan for storming Saio, Gen. Gilliaert kept in touch with British headquarters in Khartoum. The Italian officers and men retreating from Addis Ababa and Jimma under British pressure were coming daily into Saio. It was apparent that the small Belgian anvil was preparing for its test under blows by various hammers, such as was being used elsewhere by Gen. Sir Archibald P. Wavell, British commander-in-chief.

'Aggressive activity'

"I based our chances of success upon continuously keeping aggressive activity along

--20--

Bortai Brook against Mogi," Gen. Gilliaert told me, "and applying Kitchener's maxim that you can try anything against an enemy who refuses to budge himself."

Part of the booty taken from Italians after the conquest of SaioOn July 1, the British radioed the Belgians that they had cut the 450-mile-long Shio-Addis Ababa road at the Midessa River, 25 miles west from Lechenti and about 200 miles from Haile Selassie's capital. Then Gen. Gilliaert prepared to close the mouth of the Belgian bag into which the Italians were streaming.

Believing that the British pursuit was closer than it was, Gen. Gazzera blew the bridge over the Indina River, 40 miles east of Saio, thus buttoning the eastern mouth of his own bag himself. But the Congolese offensive was still a dangerous gamble because the Italians were better armed and fed, held superior positions with more fire power, and outnumbered the three Belgian battalions between three and four to one.

When the first battles of Bortai Brook had been launched, they had been preceded by three days of rain and cold which took bitter effect on men and officers. This time, a morning sun warmed the Congolese and put them in battle mood. At dawn on July 3, the Belgian advanced posts opened fire, and half an hour later all the batteries of artillery entered into action. The Italians replied with the full intensity of their superior cannonading power.

The battalion under Maj. Duperoux went forward with orders to take the two dumpling hills flanking each side of the road. The Italians had gained the hills in the second battle of the Bortai in April. Duperoux's men crept through the brush and high grass form the dumplings, which were heavily infested with machine guns.

A surprise operation

The battalion in reserve, commanded by Maj. Boniface Robyn, crawled forward behind Duperoux's left. Simultaneously, Gen. Gilliaert sent the third battalion under Lt.-Col. Edmond Van der Meersch upon the assignment that was the key to the entire operation: a long, swinging movement around the right, through grass higher than a man and along a goat path that had been carefully plotted by scouting parties over a fortnight.

The entire surprise operation was successful. The Italians, after falling back from the two dumplings, found themselves flanked upon their left by Col. Van der Meersch's forces and unable to hold the ravine of the Bortai between the dumping and the Italian secondary line of fortifications strung across the top of Saio Mountain. They melted away down hill toward the Sudanese plain upon their right. They dared not use the road for direct retreat, for it was under continuous Belgian artillery fire.

At 1:40 p.m., the encircling battalion was preparing an assault upon the Italian heights. Two Mitalia motorcars were seen descending the serpentine road toward the newly-won Belgian positions bearing white flags. In the cars were the Italian generals, Guasco, and Col. Damico, Gen. Gazzera's chief of staff. They carried the former war minister's offer of surrender.

Gen. Gilliaert met the enemy a short distance from the Belgian side of Bortai Brook. The Force Publique of the Congo had crossed Africa to gain Belgium's first victory against the Axis. Sweet revenge for the invasion of the faraway homeland!

--21--

6. "Enough," said 9 of Italy's Generals

GEN. GAZZERA'S surrender to Maj. Gen. Gilliaert, following the Duke of Aosta's surrender to Gen. Wavell of the British Middle East command, leaves the Allied arms in Ethiopia today with mastery of the situation as far as Benito Mussolini is concerned.

Final liquidation of the Fascist empire will come when the Italians holding out around Gondar decide to give themselves up to the British troops that have been surrounding and starving them since July.

Vastly outnumbered by the Italians, even after surrender, the Belgians have been hard put to handle 15,000 prisoners in the whole province of Galla Sidamo. At Saio alone, nine generals, 370 lesser officers, 2,575 Italians and 3,500 native soldiers surrendered to the Congolese force which, with 2,000 porters, aggregated hardly 5,000 men. The first Congolese officers who entered Saio alone to complete the negotiations told your correspondent today:

"We literally waded in Italians. We were embarrassed to find how many enemies had fallen into our hands. The Italians were chagrined to find that we numbered only three battalions instead of three divisions with South African reinforcements, as their intelligence service had led them to believe."

Belgians prevent looting

The proudest achievement of the Belgian general staff is that the public market in Saio has been functioning normally since three days after the fall and that no looting whatever has occurred, At near-by Mogi, when Eritreans numbering 900 found that all but 50 of the 250 Belgians originally besieging them had been withdrawn, they wished to starting fighting but were dissuaded by their Italian officers.

Belgian deaths were 462 men, both white and black, four-fifths of whom died of disease. The Italians probably lost about three times as many, although casualty figures are not available.

The younger and more belligerent Italian officers taken prisoner by the Belgians seem to blame their defeat upon the inertia and fear of the older generals. Although sympathetic with Il Duce's imperialist ambitions, they have an intense dislike for the Fascist party coterie around Mussolini, who are considered parvenus. Officers of all ranks seem to reserve their chief loyalty for the members of the Italian royal house.

Ask escort for Eritreans

In surrendering, Gen. Pietro Gazzera asked safe conduct of the Eritreans across Ethiopia

--22--

to British prison camps. This request, granted by Gen. Gilliaert, was a necessary precaution because the Ethiopian "patriots" who fought at Bure and Gore under British officers considered the disarmed Italians fair game. The 650 Italians who surrendered at Bure came into the Belgian lines almost completely naked, their garments having been purloined by the Ethiopians.

The Italian governor at Gore requested that the Belgians provide an escort of at least two of the feared Niam-Niams for each truckload of prisoners in order to prevent molestation. An Italian priest, who, contrary to Belgian advice, insisted on going out into the countryside, is still missing.

7. Secrets of jungle war

AN ATTACK upon the Belgian Congo, no matter from what quarter, can be made only at great cost to the invader, now that the Belgian forces have behind them the experience of their successful campaign against Italian strongholds in Ethiopia.

Soldiers of the Congolese Force Publique fought under the most difficult conditions in their first foreign war. They have learned the secret of resting through days of the most terrific heat, scouting strange territory under protection of the cool might and attacking at dawn. They have learned the laborious routine of constantly recamouflaging positions with bundles of elephant grass changed daily because it yellows in the tropical sun, revealing critical points.

Through Maj. Gen. Gilliaert's and Lt.Col. Leopold Dronkers Martens' tactic of continuous aggression, the Belgians have learned how a small but nettlesome force, even in a strange land, may keep a large and irresolute army upon its own territory permanently in a state of uncertainty and self-defense.

May. Antoine Duperoux, leader of the battalion now administering Saio, told your correspondent today:

Stronghold of Saio. Upper right, hill captured by Belgian troops

--23--

"Colonial warfare is the only form of encounter in battle remaining where the forces are sufficiently small that the meaning of conflict is comprehensible to the participant. Whatever else fails, a flanking movement is always possible. In such a campaign you feel the clashing wills of the opposite leaders directly instead of remotely. Colonial warfare retains here what has been lost in the mass conflict of Europe."

Explains weak strategy

In view of the relative weakness of the British Sudanese defense force when the Italians first launched their Kenya campaign, much curiosity has been felt in Belgian quarters as to why Gen. Gazzera failed to descend from the Ethiopian highland and invade the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan before the arrival of the Belgians made attack impossible. When Gen. Gilliaert addressed the question to Col. Damico, Gen. Gazzera's chief of staff, Col. Damico replied:

"Gazzera did want to attack the Sudan but received contrary orders from the Duke of Aosta, who preferred that the expedition be withheld for political reasons."

The Italians then possessed ample provisions, but when they hoisted the white flag they had hardly two months' supplies left.

Being without political aspirations and responsibilities in Ethiopia, the Belgians are withdrawing as fast as possible, leaving the police problem between the British and the Negus.

Gradually the rows of round grass huts, constructed in Congo fashion by Belgium's soldiers from elephant grass, will cease to be alien features of the Ethiopian highland. The eight 77's waiting by the Sobat River will soon be added to 10 cannon which already have made the trans-African journey to the Congo. Seventy machine guns, 122 automatic rifles, 6,900 rifles, 15,000 hand grenades and 20 tons of radio equipment, and substantial medical supplies, most in excellent condition, make up the total booty.

Repair mountain highway

Belgian road crews are preparing the dizzy Gambela-Saio highway which still bites mouthfuls from the tires of their American trucks. About a dozen Italians are at large here, and their claims for recovery of property seized by Mussolini are being heard.

The British have sent two officers with subordinates to take charge of western Ethiopia, in cooperation with Maj. John Morris, administrator of the British territorial concession at Gambela, where the Union Jack now floats. They are Capt. Sohn of Kenya, who bears the title of senior political officer of Wallega, and Capt. Kaumann of Rhodesia.

At Bure, which was taken jointly by Belgian cyclists and the King's African Rifles, a chieftain named Licht Lakau holds authority, reportedly for the Negus. At Gore, the famous Ethiopian patriot, Gen. Mosfin, a refugee in the mountains throughout the Italian occupation, has emerged from hiding, and, with numerous of his followers already gathered, will probably take a leading role in any eventual stabilization of the region. The western Ethiopian situation will continue to count much in British policy towards Egypt.

In summary of this hitherto unwritten fragment of the history of World War II, it may be said that while the King of the Belgians in prisoner among his own people, honored pictures of Leopold III and his tragically deceased Queen Astrid are hanging today above the officers' mess table here in the remotest part of Ethiopia--symbols that Belgium in Africa remembers Belgium in Europe and has begun to exact the prices of invasion from the Axis.

--24--

This series of dispatches appeared in

the New York Post and the Chicago

Daily News in October, 1941.

--25--