Chapter XV

The Battle of Britain:

The Last Phase*

(7th September-31st October, 1940)

WE MUST now retrace our steps to the autumn of 1940 in order to consider the last phase of the daylight battle in the air.

The German plan for the final stage of the struggle for air superiority over southern England was promulgated by the Air Ministry in Berlin at the beginning of September, and confirmed a few days later by an order from the Führer.1 Not altogether without reason, Fighter Command were thought to have suffered severely during the phase now ending. Perhaps fortunately from the British point of view, instead of drawing the obvious conclusion--which would have led them to continue and intensify their damaging attacks on sector-stations--the leaders of the German air force seem to have decided that their best hope of victory lay in forcing Air Chief Marshal Dowding to commit his supposed reserve of relatively unscathed squadrons to the battle. This they hoped to do by seeking objectives further inland, and of such a kind that nothing was likely to be held back from their defence. To this argument the Germans may perhaps have joined the reflection that ruthless bombing of targets less obviously military than those they had hitherto assailed might so weaken the British will to fight as to bring surrender without the pains and risks of an opposed landing. Alternatively, the same process might make possible a landing in face of little more than token opposition.

Accordingly the German plan provided that, towards the end of the first week in September, a daylight raid on London should inaugurate a series of day and night attacks on the populations and defences of large cities. After the failure of Stumpff's venture on 15th

* The strength and location of Luftwaffe units at the beginning of the last phase are shown in Appendix XVII; for the equipment and location of the defences, see Appendices XX-XXII. A summary of operations is given in Appendix XXIV.

--233--

August, the German Air Staff had wisely concluded that day attacks by weakly-escorted bomber forces on targets at any considerable distance from the coast were inadvisable; but the new decision made observance of that rule impossible unless the bomber forces now to be used in daylight were limited to the numbers for which strong escort could be found.

Strategy apart, the new plan must be seen against a background of high policy whose influence is difficult to judge but cannot be ignored. On 25th August--the night after London had been unintentionally attacked by German bombers*---aircraft of the British Bomber Command were sent to bomb military targets in Berlin. Three nights later the Germans made their first big raid on a British city by opening their series of attacks on Liverpool and Birkenhead.† The German Air Ministry issued their orders for the new phase of the battle on 2nd September, presumably after consultation with the Fuhrer, whose directive authorising the measures then announced came three days later.2 In the meantime Hitler had stated publicly, on 4th September, that raids would be made on London as reprisals for British attacks on the German capital. That night a number of German bombers laid flares over London for purposes which can only be surmised; and on the next night a sharp attack was made on Rotherhithe and other dockland areas, although according to the German programme the new phase was not due to start until the 7th. Nevertheless, it would be rash to conclude that the change in German strategy was nothing more than the culminating move in an exchange of political discourtesies. If only for lack of evidence, it cannot be said that the leaders of the German air force were not genuinely moved by the hope that a change of targets would give them the air superiority which it was their task to win.

The new phase was heralded by signs and portents which did not escape observers in this country. The Luftwaffe had begun by attacking coastal convoys during the preliminary phase of their offensive; subsequently the bulk of their attention shifted first to forward aerodromes and then to sector-stations. We have seen that Luton was attacked in daylight at the end of August; and during the next week the enemy showed manifest interest in aircraft factories on the southern and western outskirts of London, and in the industrial and dockland areas between Tower Bridge and the Nore and on both banks of the Medway. Thus there was much, apart from Hitler's speech, to suggest that a change in German strategy was imminent, though not enough to show convincingly what form it might take. In any case continued attacks on sector-stations remained the biggest danger. Measures designed to speed repair of damaged aerodromes

* See pp. 207-8.

† See pp. 211-13.

--234--

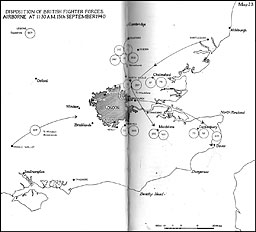

Map 22

Disposition of British Fighter Forces Airborne at 5 P.M., 7th September 1940

and their communications included the establishment of twenty-seven Works Repair Depots in various parts of the country, the posting of detachments of Royal Engineers to more than twenty Royal Air Force stations south of the Thames, and provision for specially close co-operation between the air force and the War Group set up by the General Post Office on the outbreak of hostilities. On occasions in August when attacks like those made on Biggin Hill and Kenley threatened disruption of the fighter-control system, Post Office engineers assisted by the Royal Corps of Signals performed feats which earned the respect of every airman. But Dowding and Park feared that the system might nevertheless break down if continued bombing of sector-stations enforced undue recourse to standby operations rooms and other expedients designed to cope only with brief emergencies.3

Accordingly, their plans still looked largely to the defence of aerodromes, though they also reflected increased concern for the security of certain other likely targets for the German bomber force. Since the end of August Park had been formally relieved of the obligation to provide close escort for Channel convoys; but his resources were certainly none too great for the heavy tasks which he still faced. After objectives near Brooklands aerodrome had been attacked on 4th September, the Commander-in-Chief instructed him to give 'maximum fighter cover' to factories in that neighbourhood during the next week,4 and the arrangements which he then made were so framed as to reconcile this new need with undiminished regard for the safety of his all-important sector-stations. Briefly, his intention was to offer the strongest opposition to incoming German forces after they had crossed the coast but before they reached the line of the sector-stations. The greatest number of squadrons which could safely be spared on a given occasion would therefore be sent forward of that line, in pairs if there was time to form them; and care would be taken that German bombers should not be missed through vain attempts to out-top the enemy's high cover. Adequate but not excessive numbers of squadrons would be held back to guard Kenley, Croydon and Biggin Hill; and the factories near Brooklands would look for their safety to reinforcements from No. 10 Group. Stations north of the Thames would be protected by Park's own squadrons until the arrival of reinforcements from No. 12 Group released them for the main battle.5

(ii)6

In accordance with the German plan, the new phase opened in daylight on 7th September with a raid on London and its eastern outskirts. Towards five o'clock that afternoon well over three hundred

--235--

bombers, escorted and covered by some six hundred single-engined and twin-engined fighters, were sent to attack docks and oil-installations along the lower reaches of the Thames. Some of these objectives had already suffered damage on the last two nights and in the course of daylight operations on the 5th.

When the blow fell Park was unavoidably absent from his headquarters, having been summoned to a conference at Stanmore. Whether in consequence of his absence, or because the threat developed with a gradualness which tended to obscure its gravity, or again because the picture given by radar was incomplete or because the enemy's objectives proved not to be the sector-stations round whose defence so much planning had revolved, the project which envisaged meeting the attacker in force at an early stage was not realised. The first arrival of the enemy in strength found a substantial part of No. 11 Group's resources deployed in single squadrons or smaller formations well back from the coast. (See Map 22.) Two squadrons from Northolt had formed a wing to patrol north-east of London, and one squadron, joined later by a flight from Croydon, had been sent to guard oil farms down-river, where fires kindled in earlier attacks had not yet been extinguished. In response to a request from Park's headquarters, a wing of three squadrons from No. 12 Group was on its way to protect No. 11 Group's stations north of the Thames. Meanwhile Hornchurch was guarded by one of Park's own squadrons, as was Gravesend on the south bank of the river; in addition half a squadron was just leaving to patrol North Weald, and elements of three more squadrons had been ordered to cover the line Hornchurch-Chelmsford. Other formations were over or near Canterbury, Maidstone, Beachy Head, and aerodromes just south of London.

How far these dispositions might have proved effective if the enemy had in fact attacked the sector-stations is a question which need not detain us; as it was, our forces were too weak, too widely dispersed and too far from his true line of approach to stand much chance of success in the early stages of the action. At the outset, combats were wholly or mainly with formations which had already reached their targets.7 The German vanguard would seem, however, to have been engaged on its inward course by the Thames and Medway guns, which opened fire at five o'clock on a formation flying westward; and not until some fifteen minutes later did bombs begin to fall at Woolwich, where the Royal Arsenal and two important factories were damaged. Thereafter the attackers, retiring to the north and east, were engaged by at least seven squadrons, including the pair from Northolt and the three-squadron wing from No. 12 Group. Its symmetry already broken by anti-aircraft fire, the German formation was then roughly handled by our squadrons; but the effects of the

--236--

Plate 17. German Bombers above the Thames near Woolwich, 7th September, 1940.

Plate 18. Polish Pilots of Fighter Command at Readiness in their Dispersal Hut.

Plate 19. A 25-pounder Field Gun in Action during a Practice Shoot.

Plate 20. An Anti-Aircraft Rocket Projector in Action (3-inch U.P. Single Projector).

bombing could not be undone. Moreover, while these engagements were in progress other German forces were bombing Thameshaven and dockland targets at West Ham, also without serious interference before they dropped their load.

Meanwhile yet other formations were converging on the capital from points between Beachy Head and the North Foreland. By this time there was no room for doubt that a major challenge had been offered and must be accepted; and on this occasion at least four squadrons engaged the enemy before he dropped his bombs or as he did so, including one which fought a running action over London. But for the most part German fighters were able to beat off our formations and conduct their charges in comparative safety to the dockland area on the eastern outskirts of the city. There a heavy rain of bombs not only damaged such legitimate objectives as the Mill-wall and Commercial docks, but also blasted dozens of thickly-populated streets. Further down the river there was heavy damage near Tilbury, and at Thameshaven new and vaster fires were added to those already burning. Other places hit included Crayford, Brentwood and districts of London as far afield as Tottenham and Croydon. As he retired towards half-past six the enemy was engaged by another four squadrons, including one from No. 10 Group.

Thus ended the first big daylight raid on London. On the whole it amounted to a victory for the German bombers, most of which had reached their targets without much difficulty, dropping more than three hundred tons of high-explosive and many thousands of incendiaries on and round the capital within an hour and a half. Their escort, though not as strong as the Germans would have liked to make it, had yet proved capable of clearing a way through the rather thin screen interposed by the defences. Admittedly twenty-one out of the twenty-three British squadrons ultimately used had joined action, two of them twice, but the plan of engaging the enemy well forward with pairs of squadrons had gone astray, excusably enough in view of the constant difficulty of deducing the enemy's movements from the inevitably imperfect picture furnished by radar and observation from the ground. Again, the Germans had lost more than forty aircraft; but Fighter Command's losses, amounting to twenty-eight aircraft shot down, sixteen badly damaged and seventeen pilots killed or seriously wounded, were disquieting at a time when the command was already suffering from the effects of recent onslaughts.

In face of such figures the Commander-in-Chief could no longer refuse Park the absolute priority he had been pressing for; and next day he reluctantly put into effect a 'stabilisation' scheme whereby pilots of proved ability throughout the command were mostly drafted into squadrons serving under Park or on his flanks.8 More distant sectors were forced to make do with squadrons manned

--237--

largely by unseasoned men. In addition a few squadrons assigned to an intermediate category and kept up to strength with well-qualified pilots were held ready in adjacent groups, as reliefs for No. 11 Group and its flanking sectors. The disadvantages of such a scheme, with its invidious distinctions, were obvious; and its adoption by a Commander-in-Chief who had long held out against it provides the best proof of the seriousness with which the outlook was viewed at his headquarters.

(iii)

On their retirement the German day-bombers left huge fires burning in the dockland area on both sides of the Thames below Tower Bridge, at Woolwich Arsenal, and among oil installations and factories further down the river. With only a few hours of daylight left, the fire services had no chance of extinguishing them before the onset of darkness made them into beacons for night-bombers.

From almost every point of view the outlook for Londoners on the first night of the new phase was therefore an unhappy one. The core of the great city was clearly marked out by the curving line of the Thames and the fires raging on its banks. To find so obvious a target the Germans would scarcely need their beams, so that interference with them would serve little purpose. The night air defences were ill equipped at best, and those assigned to London had been weakened earlier in the year by withdrawal of guns to newly-threatened targets. As compared with the 480 heavy anti-aircraft guns allotted to London and the Thames and Medway defences by the Committee of Imperial Defence before the war, only ninety-two were deployed in the inner artillery zone, another hundred and twenty on the Kent and Essex marshes and fifty-two on the western outskirts of the capital.* The total of 264 was thus well short of the pre-war figure, recently confirmed by a fresh examination of the problem.9 In the fighter sectors guarding London there were two squadrons of night-fighters equipped with Blenheims, but Hornchurch aerodrome was so thick with smoke from neighbouring fires that when the time

* These figures were made up as follows:

| 1st A.A. Division |

| |

Inner artillery zone |

92 |

| |

Langley, Hounslow, Stanmore |

36 |

| 5th A.A. Division (part) |

| |

Brooklands |

16 |

| 6th A.A. Division (part) |

| |

Thames and Medway |

120 |

| |

264 |

For further details, see Appendix XXII.

--238--

came the squadron based there could not get its aircraft off the ground. In addition, a section of single-seater fighters in each of No. 11 Group's seven sectors would normally have been available to supplement the Blenheims; but single-seater fighters were notoriously ineffective at night except when visibility was very good, while every available aircraft and pilot would almost certainly be needed for day fighting as soon as the sun rose again. In the circumstances Park took the responsibility of making practically no call on his day fighters once the afternoon's attacks were over. Thus the burden of defending London against its first big night raid fell mainly on the one remaining Blenheim squadron and on guns, balloons and searchlights.

The first of the night-bombers left France about eight o'clock and reached the English coast near Beachy Head some twenty minutes later, when darkness had not yet settled in. Two Hurricanes from Tangmere were in the air close by, but were not diverted from their routine task. The German vanguard flew unhindered to Battersea, where the first bombs fell soon after half-past eight, the guns of the inner artillery zone not opening fire until nine o'clock. Thereafter the guns were in action intermittently until three o'clock next morning, unfortunately to little purpose. A method of fire based on two lines of outmoded sound-locators east and west of London failed utterly, bombers from the south being able to outflank the system, while even those which did approach from the expected quarter were often missed or incorrectly tracked.10 Failing communications further increased the difficulties of the gunners, some parts of the front going out of action for long periods. The Thames and Medway guns were also called upon, but many of those on the south bank of the estuary were too far east to deal with bombers approaching from the south, while those north of the river necessarily fired mostly at aircraft which had already dropped their bombs. The Portsmouth and Southampton guns were likewise busy with incoming and outgoing bombers from twenty minutes past eleven until dawn, but were no more successful. Two aircraft of the only Blenheim squadron able to go into action patrolled north-east of London for three hours before midnight, and another went up later in the night, but their crews saw nothing of the enemy. A Blenheim and a Beaufighter of the experimental Fighter Interception Unit, both equipped with airborne radar, were also on patrol, but they too drew blank.

Thus for nearly seven hours German bombers were able to fly over London unimpeded by our fighters, though hindered by balloons and anti-aircraft fire which at least prevented them from closing to point-blank range. Between them Luftflotten 2 and 3 despatched about two hundred and fifty aircraft, of which the vast majority bombed London, aiming some three hundred and thirty tons of high-explosive and four hundred and forty incendiary-canisters at Silvertown and at

--239--

districts on both banks of the Thames from Vauxhall Bridge to Putney Bridge. About nine-tenths of their load came down within ten miles of Charing Cross. The riverside boroughs east of the City, already sorely tried in daylight, suffered most, but almost every district was affected. Power stations at Battersea and West Ham sustained hits which forced them to close down, the London and North-Eastern Railway was cut at several places, Victoria Station was blocked so that only a few trains could get in or out of it, and traffic to London Bridge station had to be suspended. In dockland, and down-river where tidal waters lap the Kent and Essex marshes, the huge fires kindled in the last few days were still burning when dawn broke over the battered city, and indeed continued to burn for many days.* In the course of 7th September and the succeeding night about a thousand Londoners lost their lives.

(iv)

On 8th September bad weather, and probably also the strain of recent operations, limited the Luftwaffe to minor raids of little consequence. On the 9th the Germans returned to the attack in force, although the weather was still far from perfect. Again the blow fell almost wholly on London and south-east England, but this time the defences did much better. Whereas German crews returning from England on the 7th had commented on the weakness of the opposition, on the 9th they reported strong resistance by fighters south of London and spoke highly of Fighter Command's tactics.11

Once more the main attack came late in the day, as if to pave the way for the night's bombing. At half-past four the growing strength of German patrols above the Straits led No. n Group to post a squadron over Canterbury; and by five o'clock nine squadrons of the group were airborne over Essex, Kent and Surrey, including a pair of Hurricane squadrons over Rochford. A quarter of an hour earlier Park had asked for reinforcements from Nos. 10 and 12 Groups to guard aircraft factories in the Thames Valley and sector-stations north of the Thames Estuary.

Meanwhile the leading German formation had crossed the coast near Dover. Coming east from Maidstone, the Spitfire squadron posted there engaged it over East Kent and was soon joined by another already in the neighbourhood. Abandoning their primary objective, most of the bombers thereupon dropped their load on Canterbury and the surrounding countryside before wheeling westwards over the Sussex border, where they were engaged by three

* For an account of the subsequent course of the night offensive against London, see Chapter XVI.

--240--

more squadrons. A second wave approaching over Beachy Head was likewise met well forward by two squadrons, but continued towards south-west London, where another squadron from No. 11 Group and a wing from No. 12 Group were in action shortly afterwards. Determined opposition and indifferent visibility gave the bombers little chance of taking careful aim, with the result that their bombs were widely scattered over districts as far apart as Epsom on the one hand and Lambeth on the other. Intermediate places which reported hits included Kingston, Richmond, Maiden, Surbiton, Norbiton, Purley, Barnes, Wandsworth, Lambeth and Chelsea. Altogether about ninety bombers reached London and its outskirts, dropping about a hundred tons of bombs there, while another fifty or sixty were turned back and some seventy diverted to secondary targets of small value. Eighteen German aircraft crashed on land or within sight of the coast; but altogether twenty-eight were lost. With nineteen aircraft shot down and only fourteen pilots missing, killed or wounded, Fighter Command had much the best of the exchange. Admittedly lack of time to form two-squadron wings had again forced many of Park's squadrons to go into action singly; but their attacks were well-timed and generally effective. And if the unexpected move which brought the No. 12 Group wing so far south and west of the objectives they had been asked to guard was disconcerting to No. 11 Group, the practical value of their intervention seemed undeniable.12/^-

The strength and effectiveness of the British response on this day surprised the German High Command, but did not extinguish their hope of achieving air supremacy within the next few days. We have seen that on the nth Hitler postponed announcement of his decision regarding 'SEALION' until 14th September.* The 10th was another quiet day; but on the afternoon of the nth about a hundred bombers attacked London. They went chiefly for the City and the docks, though some of their bombs fell further north at Islington and Paddington. At the same time a smaller force attacked the outskirts of Southampton. In repelling these and other raids on the nth Fighter Command lost twenty-nine aircraft, while German losses for the day were twenty-five. Over-estimating the losses inflicted on the enemy, the defences believed that the Luftwaffe had suffered a bad setback, but the impression received by the German High Command was very different.13 After yet another quiet day on the 12th, they concluded on the 13th that air supremacy was by no means out of reach. And indeed, in a very hopeful appreciation made on that day, Hitler went so far as to imply that victory in the air might soon relieve him of the disagreeable duty of deciding whether or not an opposed crossing of the Channel should be attempted.14

* See Chapter XIV.

--241--

These hopes received apparent confirmation on the 14th, when further attacks on London were ineffectively opposed and both sides lost fourteen aircraft. They were, however, shattered on the morrow, when the air defences achieved their biggest triumph since mid-August.

In Great Britain 15th September is annually celebrated as 'Battle of Britain Day', the date having been chosen largely because about a hundred and eighty German aircraft were at one time thought to have been shot down on that day in 1940. In fact the number destroyed was only a third as large; but the day was nevertheless one of the most important of the whole battle. If 15th August showed the German High Command that air supremacy was not to be won within a brief space, 15th September went far to convince them that it would not be won at all.

At dawn on that memorable Sunday the weather over southern England was fine and visibility was good. But as the day wore on clouds gathered over Kent and Sussex, so that by the middle of the afternoon an opaque screen between four thousand and six thousand feet above the ground extended over a great part of both counties. Fighting began a little before midday. During its early stages, and later through occasional breaks in the clouds, spectators on the ground were able to watch as much of its progress as was revealed by brief glimpses of aircraft shining in the sun and by vapour-trails which their passage traced across the sky. Widespread awareness that the authorities had been expecting invasion for the last week, and that much hung on the issue of the combats daily fought four miles above the fields and houses of south-east England, gave special poignancy to events in which large forces were visibly at work.

The German plan of operations comprised a series of raids on London by about two hundred and twenty bombers of Luftflotte 2, and attacks on Portland and the Supermarine Aircraft Works outside Southampton by some thirty of Luftflotte 3. Supporting fighters flew some seven hundred sorties. Luftflotte 3 's attack on Portland was timed to catch No. 10 Group at an awkward moment when the Middle Wallop sector was busy reinforcing No. 11 Group; but the main offensive was weakened by division into two distinct phases, separated by an interval which gave defending squadrons time to refuel and rearm before they made their second sorties.

A further weakness of the German plan was its neglect of the usual feints and false alarms. Formerly a gradual strengthening of patrols across the Straits had often preceded well-contrived diversions which threatened to catch Park or his deputy in two minds. This morning the massing of aircraft above the French coast left no doubt by eleven o'clock that a big attack was imminent. Half an hour then elapsed before the leading German aircraft reached the English coast, and

--242--

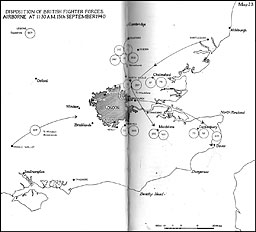

attempts to provoke No. 11 Group to a false move in the interim were too perfunctory to serve their purpose. The delay gave time for the deployment of seventeen British squadrons, including one from No. 10 Group and five from No. 12 Group, in good positions to meet threats from east or south. (See Map 23.) Ten of the eleven squadrons of No. 11 Group were despatched in pairs, while the three Hurricane and two Spitfire squadrons sent by No. 12 Group came south in a single tactical formation, impressive even by Teutonic standards.

By the time the German vanguard reached East Kent the cards were therefore stacked in favour of the defenders. A pair of Spitfire squadrons posted over Canterbury went into action within the first few minutes and were soon followed by the single squadron at Dover and a pair patrolling Maidstone. Almost at the same instant Park threw in six more squadrons which he had been holding in reserve, and shortly afterwards two of them came in contact with the enemy near the Medway towns. Continuing to the outskirts of London, the first wave of German bombers and their escort then fell foul of two pairs of Hurricane squadrons which had moved south after each pair had joined forces over Essex. Immediately afterwards the big wing from No. 12 Group took up the fighting, the three Hurricane squadrons engaging the bombers while the Spitfires took on German fighters. During the last two engagements the bombers dropped their load with little attempt at accuracy on London and its outskirts from Beckenham to Westminster. Houses were destroyed or damaged at Camberwell, Lewisham, Battersea and Lambeth; two bridges and a suburban electricity works were hit and damaged; and a bomb descended in the grounds of Buckingham Palace, but failed to explode. Thereafter four more squadrons engaged the enemy as he retired in two distinct formations over Kent and Sussex.

The second and heavier attack on London came about two hours later. The warning was shorter than in the forenoon, but gave time for six pairs of squadrons from No. 11 Group to take up positions over Chelmsford, Hornchurch, Sheerness, Northolt and Kenley while the leading German aircraft were still over the Channel. As the enemy approached the English coast No. 11 Group put up another seven and a half squadrons, four of them in pairs, while No. 12 Group again contributed five squadrons in a single tactical formation, and No. 1 o Group one squadron. Originally posted over Middle Wallop, the last was later transferred, with a second squadron, to the Kenley-Brooklands line.

Crossing the coast between Dungeness and Dover a little before twenty minutes past two, the attackers flew towards the capital in three formations. One was intercepted near Canterbury by a pair of squadrons ordered south from Hornchurch and later by a flight of

--243--

Hurricanes posted over Maidstone; further west two squadrons moving north from Tangmere engaged another near Edenbridge and saw some of the bombers jettison their load and turn away while the majority continued towards London. Later Group Captain S. F. Vincent, commanding the Northolt sector, came in contact with the same force and had the satisfaction of seeing some of the bombers turn back in consequence of his single-handed attack delivered from head-on. The bulk of the fighting took place over London and its outskirts from Dartford westwards, where five pairs of squadrons from No. n Group and the wing from No. 12 Group were all in action between ten minutes to three and a quarter past, mainly with the third formation but probably also with survivors of the other two. In the course of the action the enemy distributed a big bomb-load over London and its outskirts, scoring several lucky hits on public utilities and railways. At East Ham a gas-holder and a telephone-exchange were wrecked; and considerable damage was done to a variety of targets on both banks of the river at West Ham and Erith. Many other riverside boroughs reported hits; but the harm done was nothing like as great as that sustained eight days before in the first of the big daylight raids on London. Again retiring by two distinct routes, the attackers were engaged on the way out by another four squadrons, including two from No. 10 Group. Guns of the inner artillery zone and the Thames and Medway defences were also in action and claimed a number of successes.

The fighting over London was at its height when a small force, apparently consisting of bombers without fighters, crossed the Channel to threaten Portland. The radar chain gave more than half-an-hour's warning, but underestimated the strength of the oncoming force. Moreover, luck or skill enabled the attackers to approach by such an unexpected route that only one gun-site at Portland was able to engage them. To make matters worse, reinforcement of No. 11 Group had reduced the available strength of the Middle Wallop sector to a single squadron, which succeeded in bringing the enemy to action only as he retired. Fortunately the bombing did little harm, the dockyard escaping with minor damage. About six o'clock another small bomber force, this time escorted by twin-engined fighters, approached the Hampshire coast. Twenty minutes' warning gave Nos. 10 and 11 Groups time to put four squadrons in the air before the enemy's arrival and follow with a fifth, but none succeeded in joining action until the attack was over. Engaged meanwhile by the Southampton guns, the bombers missed their target but damaged property close by.

In the course of the day Fighter Command lost twenty-six aircraft. Between them pilots and gunners claimed to have shot down a hundred and eighty-five German bombers and fighters. In fact the

--244--

Map 23

Disposition of British Fighter Forces Airborne at 11:30 A.M. 15th September 1940

Luftwaffe lost sixty aircraft, a number amply sufficient to strain a force already battered by nine weeks of unprofitable fighting.

(v)

A natural result of the setback suffered by the Luftwaffe on 15th September was to cast doubt on the methods and tactics adopted since the beginning of the current phase. Since the 7th the German air force had lost more than two hundred aircraft, including nine destroyed on the ground by British bombing. More than half of them were bombers. British accounts of the fighting suggest that many of these losses were due to insufficiently close fighter escort. German bomber-crews received the same impression.15 German fighter-pilots, on the other hand, protested that close escort of slowly-moving, heavily laden bombers flying very high was beyond their powers, and that the Messerschmitt 109, successful as it was in attack, was less suited to a purely defensive role than the 'slower but more manoeuvrable' British fighters.* In order to keep pace with their charges, escorts were forced to fly a devious course which removed them periodically from the bombers without conferring the freedom of action inherent in a less rigid system. Asked to adjudicate in the dispute, Göring gave his opinion in favour of the bombers.16

Meanwhile, on 16th and 17th September, bad weather precluded daylight raids on London, and on the latter day the Führer ordered the indefinite postponement of'SEALION'.† Whatever factors may have led to his decision, outwardly at least it signalised the failure of Göring and his men to live up to their reputation. Thereafter the German High Command, abandoning the hope of a rapid victory achieved in daylight raids, fell back on the combined effects of night bombing and maritime blockade to weaken British resistance while they made ready for more spectacular adventures in the east.

Even so the daylight battle was not over. Not until October brought declining weather was the German effort drastically reduced, and even then attacks on London were made whenever the skies were suitable. Throughout the rest of September small bomber-forces raided London daily when the weather was favourable, and during the same period several bold attacks were made on aircraft factories. Besides providing escort and cover for the larger raids, fighters made diversionary sweeps, and sometimes fighter-bombers were employed.

Fighter Command continued, therefore, to be well extended,

* When asked by Göring what he needed to improve his chances, the commander of Jachdgeschwader 26 claims to have replied, 'I request that my Geschwader be equipped with Spitfires.' This demand is said to have left Göring speechless.

† See Chapter XIV.

--245--

though a lower scale of attack and diminished losses on most days during the latter half of September brought some relief. By the middle of the month gross wastage of Hurricanes and Spitfires had fallen below output, so that reserves began to increase again. On the other hand, the chronic shortage of fighter-pilots called once more for heroic measures on 18th September, when the Air Ministry agreed to a further combing of the Battle squadrons for Fighter Command's benefit. They also agreed to allot to the command more than two-thirds of the entire output of the Flying Training Schools in the four-week period ending in the middle of October.

Like his counterparts across the Channel, Park found occasion after the 15th to review the lessons of the last few days. Too often squadrons detailed to work in pairs had failed to join forces, sometimes because they had been given points of junction so far forward that they came upon the enemy before they met their partners.17 At times diversionary sweeps by German fighters had drawn up nearly the whole strength of the group, and sometimes pairs of squadrons had been so disposed as to invite a swoop by the enemy's high cover.18 He told his group and sector controllers, therefore, to make special arrangements in future for the engagement of high-flying German fighters by pairs of Spitfire squadrons, and to muster squadrons in such positions that they were not likely to be dived upon while still climbing. When high-flying German fighters were known to be approaching, ample Hurricane squadrons must be paired in the neighbourhood of sector aerodromes, and waiting squadrons in the outlying sectors must be warned for action against further enemy formations not yet in evidence. The lesson of the battle was that successful action against the kind of raid the enemy had learnt to make since August depended not merely on getting up enough squadrons in the early stages, but also on so adjusting the readiness of those left on the ground that a tactical reserve could be brought in at the crucial moment.

Here Park was met by the difficulty that, while the wing habitually sent south from Duxford and its neighbouring sectors by No. 12 Group was capable of providing such a reserve if its movements were concerted with those of his own squadrons, he had no means of bringing this about. Air Vice-Marshal Leigh-Mallory, commanding No. 12 Group, naturally wished the reinforcing squadrons to be controlled by one of his own sectors. Nevertheless he was unwilling to see them confined to the minor task of guarding sector-stations north of the Thames Estuary while major actions were going on elsewhere. Consequently No. 11 Group were more than once surprised to find the Duxford squadrons in the thick of the fighting when they were supposed to be well away on the left flank. Moreover, Park was worried lest his neighbour's preference for large formations should retard

--246--

the arrival of the reinforcing squadrons. Reminded that twice in August stations in No. 11 Group had been bombed when No. 12 Group had been asked to guard them,1 Leigh-Mallory retorted, perhaps unfairly, that his squadrons were usually called in too late. Somewhat complex changes of procedure were needed to give No. 12 Group independent warning of raids approaching their neighbours' flank, and to enable Uxbridge to follow the movements of the Duxford wing. And amidst the preoccupations of the battle they were not made until October was three-parts over.19

On the whole, No. 11 Group's arrangements for the second half of September worked well when the group found anything to bite on. German crews attacking London and other targets in south-east England paid frequent tribute to the strength of the defences.20 On the 18th, 27th and 30th, when the number of bombers which claimed to have reached the capital and its outskirts varied from twenty-seven to nearly seventy a day, the defences fought notably successful actions, German losses for the three days amounting to more than a hundred and twenty aircraft, while Fighter Command lost only sixty.

On the other hand, the Germans succeeded in making several damaging attacks on aircraft factories, sometimes using single aircraft and sometimes fairly large formations. On the 21st a single bomber made a daring raid on the Hawker factory at Weybridge from five hundred feet, though fortunately the damage done did not affect production. Three days later from fifteen to twenty aircraft attacked the Supermarine Works at Woolston near Southampton in two waves, doing little damage to the factory itself, but hitting an airraid shelter and killing or wounding nearly a hundred of the staff. On the 25th a more ambitious effort against the Bristol Aeroplane Company's establishment at Filton was undertaken by nearly sixty bombers of Luftflotte 3, accompanied by fighters, while fighter-bombers made a diversionary attack on Portland. No. 10 Group put up three squadrons and a section as the enemy approached, but began by ordering them to Yeovil, where the Westland factory seemed a likely target. When the true objective became clearer, three of the squadrons set off in pursuit, but only a few aircraft caught up with the bombers before they reached their target. Dropping ninety tons of high-explosive and twenty-four oil-bombs, the attackers severely damaged the main assembly works and other buildings, with the result that production remained below normal for many weeks. Moreover the bombing killed or wounded more than two hundred and fifty people, blocked railways near the factory, and cut communications between Filton aerodrome and group headquarters.

* See pp. 209 and

214.

--247--

The German formation was further engaged after the bombing, and altogether lost five aircraft, including one shot down by anti-aircraft fire.

Although Filton was serving temporarily as a sector-station, no fighters were based there on the 25th, the squadrons allotted to the sector being at Exeter and Bibury. On the next day Dowding took the exceptional precaution of sending No. 504 (County of Nottingham) Squadron from Hendon to Filton for the express purpose of guarding the factory in future. The move was timely, for on the 27th ten twin-engined fighter-bombers with an escort flew to the neighbourhood to attack either Filton itself or some other target close to Bristol. No. 504 Squadron met them near the city and, as the German crews admitted, kept them from their target, so that they dropped their load unprofitably on the suburbs. The Bristol guns and pilots of three other squadrons helped to give the attackers an impression strongly at variance with current reports of British weakness.

Meanwhile, on the 26th another attack on the Supermarine factory at Woolston had been attempted, this time by some fifty escorted bombers and fighter-bombers. They dropped nearly seventy tons of bombs to such good purpose that for a short time production was completely stopped. In addition, more than thirty people were killed, and at Southampton a warehouse filled with grain was totally destroyed. Engaged on the way in by anti-aircraft fire only, the attackers were afterwards set upon by four squadrons from Nos. 10 and 11 Groups, losing three aircraft as compared with six aircraft and two pilots lost by the defenders. Finally, on the 30th about forty escorted bombers which sought to attack the Westland factory at Yeovil were engaged on their way in by at least four squadrons and by four more near their destination or after they had left it. They were also hampered by dense clouds which hid the target, forcing them to estimate its position by dead reckoning. Consequently they missed the factory, hitting instead the neighbouring town of Sherborne and the railway close by, so that traffic had to be temporarily diverted.

(vi)

As the autumn drew on, the Luftwaffe reduced the proportion of bombers to fighters used in daylight. They took to sending towards London small formations of fighters, either unaccompanied or escorting only modest striking forces often composed of single-engined fighter-bombers. Where bombers were used the German authorities favoured the Junkers 88, their fastest bomber, but one whose reputation when first introduced was summed up in a report by the

--248--

Inspector-General of the Luftwaffe that crews had no fear of the enemy but were afraid of the Junkers 88. Attacks on aircraft factories by unaccompanied single bombers or small formations continued in October, but sweeps by fighters and fighter-bombers were the dominant feature of the month.

These tactics were difficult to counter, first because of the height at which the German fighters flew. Above 25,000 feet the Messerschmitt 109 with two-stage supercharger had a better performance than the Mark I Hurricane or Spitfire. Mark II versions of both aircraft were coming into service, but at great heights the enemy still had the advantage. Moreover, raids approaching at 20,000 feet or more had a good chance of escaping radar observation and were difficult for the Observer Corps to track, especially when there were clouds about. Secondly, the speed at which formations unencumbered by long-range bombers flew was so great that at best the radar chain could not give much more than twenty minutes' warning before bombs carried by fighter-bombers fell on London. Thirdly, Park and his controllers had no means of telling which of several approaching formations contained bomb-carrying aircraft and should therefore be given preference.

A step towards the solution of the second and third problems was taken at the end of September, when No. 421 Flight (later No. 91 Squadron) was formed for the purpose of spotting approaching formations and reporting their height and strength to Uxbridge by radio-telephony. Although told to fly high and avoid combat, pilots so employed were sometimes taken at a disadvantage. After four had been shot down in the first ten days they began to work in pairs, a practice later generally adopted. But in any case their efforts were not a sufficient answer to the problem of intercepting raiders which flew too high for detection by the radar chain. At the end of the first week in October, Park was therefore forced to maintain patrols by at least one squadron when high-flying raids were likely. Beginning with a patrol at 15,000 feet between Biggin Hill, Maidstone and Gravesend by a single Spitfire squadron, he found himself obliged in the middle of the month to add a second patrol by one Hurricane squadron in the morning and early afternoon, and later to order continuous patrols by two squadrons whenever the weather favoured high-flying raiders.21 These measures were expensive in flying-time but were followed by a notable improvement in the ratio of interceptions to sorties when the enemy appeared.

The result was that, while a fairly high proportion of small bomb-carrying formations reached their targets without serious interference, the achievement of the defences in terms of casualties suffered and inflicted continued to be satisfactory. In the whole of October Fighter Command lost one hundred pilots killed and sixty-five

--249--

wounded, or altogether about half the total for September.22 German losses were swelled by growing wastage among night-bombers landing on indifferent aerodromes; but of the 328 aircraft of all types destroyed or irreparably damaged in October, probably about two hundred succumbed to the defences in daylight raids.23 A gradual weakening of the Luftwaffe as winter drew on was thus accompanied by a slight but perceptible strengthening of the British fighter force, unhappily offset by the growing demands of the night battle. At the end of the month the average number of pilots in Dowding's squadrons was just under twenty-three, a figure which included many not yet fit for active operations. Moreover, the unwelcome stabilisation scheme was still in force. On the other hand, the last week of October found the Aircraft Storage Units holding a bigger reserve of Hurricanes and Spitfires than at any time since August. But these figures scarcely justify the popular impression that the fighter force was stronger at the end of the battle than at the beginning. For when the battle ended Fighter Command's casualties, apart from wounded, included nearly four hundred and fifty officers and other ranks who had lost their lives in the fighting since July; and among that number were many whose skill would not easily be matched by their successors.* The battle had been won, but by a margin whose narrowness was apparent only to those who had studied its progress in all its aspects and through all its phases.

* For details, see Appendix XXV.

--250--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (14) *

Next Chapter (16)