Landings at Cape Torokina

D-DAY, 1 November 1943, dawned bright and clear.1 General Quarters had been sounded at 0500,2 and troops lining the rail at 06143 saw a beautiful sunrise which outlined Bougainville's forbidding mountain range. Wisps of smoke curled into the sky from the great jungle-surrounded volcano, Mt. Bagana. The atmosphere was tranquil.4

The task force had proceeded without incident and at 0432, 1 November, course was set to approach Cape Torokina, while speed was reduced to 12 knots. Minesweepers swept clear lanes about 6,000 yards ahead of the transports.5

The sweepers found no mines and reported sufficient water for the transports, which then began to enter the transport area about 0545,6 with Hunter Liggett in the lead. Upon reaching a point about 3,000 yards off Cape Torokina, each transport executed a 100° turn to port and took the point itself under 3-inch fire. When abeam, Puruata Island was taken under 20mm fire.7 At 0637, Admiral Wilkinson announced 0730 as H-hour.8 By 0645, when all transports were anchored in line in the transport area, about 3,000 yards from the beach, the AK's being in parallel line some 500 yards to seaward, the traditional signal "land the landing force" was thereupon executed.9 Marines clambered over the sides to take their places in the LCVP's and LCM's. In the first trip of the boats, approximately 7,500 troops were to be landed on beaches some 1,500 yards away from the line of departure.10

The signal to start the first assault wave for boats of the President Adams (carrying elements of the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, reinforced),11 which had a 5,000 yard run to the beach,12 was executed at 0710.13 Simultaneously the fire-support destroyers Anthony, Wadsworth, Terry, and Sigourney, which had been firing intermittent missions since about 0547, commenced their prearranged fires. This fire lifted at 0721, and immediately thereafter 31 TBF's of Marine Air Group 14, flying from Munda, bombed and

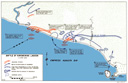

Map 3

Initial Landings

Cape Torokina

1 Nov 1943strafed the beaches for about five minutes.14 First boats to hit the beach were those of the Jackson (carrying elements of the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, reinforced), which grounded at 0726, four minutes before H-hour.15

By approximately 0730, white star parachutes,16 indicating "Landing Successful", were seen going up from several of the beaches, despite varying degrees of resistance.17

The Japanese defenders of Cape Torokina on 1 November consisted of the 2d Company, 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry plus 30 men from the Regimental Gun Company. In addition to their organic weapons, this force was equipped with one 75mm gun. Total strength numbered approximately 270 officers and men under command of Captain Ichikawa, in prepared positions consisting of 18 pill-boxes, solidly constructed with coconut logs and dirt, and connecting trenches and rifle pits. Of this force, one platoon was stationed on Puruata Island and one additional squad on Torokina Island. The 75mm gun was emplaced on the shoulder of Cape Torokina near Beach GREEN 2, and riflemen were disposed around the gun. All other beaches were undefended. The Japanese had based their dispositions on an estimate that Allied forces would attack east of Cape Torokina and west of Cape Motupena.

It was not until 5 November, that survivors of the 2d Company, 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry, had their first opportunity to take stock. Only 68 officers and men had been able to escape the Marine

OVER THE SIDE--Men of the 3d Marine Division clamber down a cargo net into an LCM waiting to land them at Torokina on the morning of D-day.onslaught. Captain Ichikawa, wounded in action, had been replaced as commanding officer of the defending force by the Probationary Officer who commanded the 2d Platoon.18

The schedule of the 3d Marines provided for simultaneous landing by four landing teams on beaches from Cape Torokina to the Koromokina River, the 1st Battalion landing on Cape Torokina (Beach BLUE 1), the 2d Raider Regiment (less the 3d Battalion) landing west of the 1st

A MARINE DIVE BOMBER from VMSB-144 turns gently toward the beachhead area prior to peeling off in one of the prelanding airstrikes at Torokina on D-Day morning.Battalion (Beach GREEN 2), the 2d Battalion to the west of the Raiders (Beach BLUE 2), and the 3d Battalion between the Koromokina and the 2d Battalion (Beach BLUE 3). The 9th Marines scheduled landings of its 1st, 2d, and 3d Battalions from left to right in that order on Beaches RED 3, RED 2, and RED 1, and provided for simultaneous landing of the 3d Raider Battalion (less Company L, which landed on Beach GREEN 2) on Beach GREEN 1, Puruata Island, in order to destroy all anti-boat defenses which might be emplaced there.19

When boats of the 3d Marines came in line with Puruata Island, they were taken under three-way crossfire of machine-guns on the Cape, the western tip of Puruata Island, and Torokina Island.20 Fortunately, casualties from this fire were light, but LCP's (landing craft, personnel), being employed as command boats by boat group commanders, because of their distinctive appearance as compared with LCV's (landing craft, vehicle), were easily identifiable for what they were and thus were well worked over while in range of Japanese guns.21

Having passed Puruata Island safely, boats of the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines approached their beaches on the western side of Cape Torokina, only to be taken once again under machine-gun and rifle fire, this time from positions on the Cape itself. These positions were in well concealed log and sand bunkers, many of which were joined by connecting trenches. On the northwest shoulder of the cape, on the Raider's beach, a 75mm Mountain gun was emplaced in a coconut log and sand bunker, protected by interconnected

rifle positions. The area to seaward from the Cape past Puruata Island and the channel to the north was covered.22 As the boats came into range, this gun began to fire at them, and succeeded in destroying about four and damaging ten others with 50 high explosive shells.23

Typical of all these boats was No. 21, of the Adams. Embarked were Lieutenants Byron A. Kirk and Harris W. Shelton, with two squads of Kirk's 2d Platoon, Company C; a detachment of 1st Battalion Headquarters Company; and a demolition squad, Company C, 19th Marines. Less than 20 seconds before this boat was to reach the beach, three shells from the Japanese 75 hit the boat in rapid succession. The first shell killed the coxswain and put the boat out of control, while the second and third shells killed both lieutenants and 12 enlisted men, while wounding 14 others. Some survivors, under Sergeant Dick K. McAllister, went over the side, and by aiding one another were able to get to the beach, where they immediately engaged the Japanese defenders with rifles and hand grenades.24 Since the only way to get aid for the wounded was to get them back to the ship, Corporal John McNamara decided to attempt to get the boat underway. By this time the boat had drifted up on the beach, so McNamara and a seaman climbed aboard and backed it into the sea. Having been damaged, however, the craft was not seaworthy, and therefore sank. Only four or five of the wounded survived.25

In the meantime the Boat Group commander's boat had been shot to pieces by the 75, and the boat waves were completely disorganized.26 As a result, assault companies of the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, landed in an order practically the reverse of that planned. To make matters worse, the Japanese opened up with their beach defense

LANDING CRAFT UNDER FIRE ROUNDING PURUATA ISLAND on the way in to the beach. At this point, assault waves were also receiving enemy fire from Torokina Island, in left background, and from Cape Torokina itself (not shown).

Map 4

Enemy Defenses

Cape Torokina

31 Oct 1943machine-guns, and those Marines who were able to get ashore unscathed had to cross the beach through a hail of fire. In spite of disorganization of units and the wounding of the 1st Battalion commander, Major Leonard M. Mason, early in the attack, impromptu but aggressive individual action soon got the situation in hand and insured successful completion of the landing.27

By the time the shore had been gained, entire organizations were broken up. Platoons and companies were thrown out of position by being landed on the wrong part of the beach; contact was lost between companies; the battalion lost communication and therefore control of its subordinate units. This condition, brought about by cannon fire, emplaced and coordinated machine-guns, and by high dense brush that grew nearly to the water's edge, might have resulted in destruction of the entire force if it had not been for the presence of an unusually large number of individuals who had received thorough training as small unit leaders, and who knew the mission and were ready and willing to take charge in a crisis. Because every Marine had been thoroughly indoctrinated and briefed on the entire maneuver, each was able to carry out the mission in the sector

APPROACHING THE BEACH, landing craft machine-gunners spray the shoreline with .50 caliber fire which may help to keep Japanese defenders pinned to their positions, and hold down enemy fire during the last minutes of the approach.

THE FINAL RUN IN of an LCVP to the beach, while a torpedo-bomber of Marine Air Group 14 makes a last pass at the smoking jungle.in which he found himself, even though he may have been landed in the wrong place. What is more, these men went on to complete the mission assigned to that sector without direction from higher echelon, achieving spontaneous unity of effort and attaining their objectives despite absence of control.

Stress which had been laid on small unit training, particularly in rifle squad and platoon tactics, now paid a dividend. Until the beach defense and its supports were overcome, the battle was one of small groups, composed of men, sometimes not even of the same squads, but in every case taken in charge by some Marine whose instinct for leadership enabled him to meet the emergency.

Attacks were well coordinated, well led, and well executed, and as a result the Marines who got safely ashore eventually reached each battalion's objectives where, with little delay, units somewhat automatically reorganized and either shifted position to the sector originally assigned, or merely exchanged responsibility for the sector with the consent of the battalion commander. Company C, which had been landed on the extreme right flank in place of Company A, which had been scheduled to land there, suffered particularly heavy casualties.28

ON THE BEACH AT LAST, 3d Division Marines fan out on the double to get across the exposed shoreline and plunge, already deployed for combat, into Bougainville jungle.That the troublesome 75mm gun did not succeed in causing an even greater number of casualties and increased havoc among the landing forces was due, in large measure, to a considered act of great bravery by Sergeant Robert A. Owens, Company A, 3d Marines.29 Realizing that rifle fire and grenades were gaining no results in silencing the gun, he posted four comrades to cover with fire the two rifle bunkers adjacent to the gun position. As his mates were moving into position to take up fire on these bunkers, Owens observed them being shot one by one, but, realizing that once having begun the assault it would be useless to stop, he advanced toward the gun position alone, being hit several times on the way. Owens continued his assault nevertheless, entered the gun position through the fire port, killed some of the gun crew, and drove the remainder through the rear door, where they were instantly shot. His charge carried him just clear of the emplacement where he fell dead of the wounds he had received. It was afterwards discovered that a round had been placed in the gun chamber and that the block was nearly closed. Thus Owens undoubtedly prevented the gun from destroying additional lives. As a result of his action, Sergeant Owens was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.30

There is no doubt but that seizure of the Cape was the key to success. Through the vigorous

efforts of Major L. M. Mason order appeared out of chaos. Although wounded, Mason refused to be evacuated until he was sure the landing of his battalion had been successful.

While the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines was involved in fighting on the Cape, elements of the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, and the 2d Raider Battalion were also engaged. These units likewise had to land in the face of rifle and machine-gun fire and having been landed out of position, had become thoroughly disorganized on reaching the beach.31 Companies were forced to move laterally on the beach, under fire, in order to reach their proper positions. In an effort to prevent additional confusion or immobilization by Japanese fire, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph P. McCaffery, Commanding Officer of the 2d Raider Battalion, moved under fire from mortars and automatic weapons, from unit to unit in order to dispose those units to insure maximum effectiveness of the troops. Initiating an attack which ultimately led to reduction of the Japanese positions, McCaffery led his men until he was felled by enemy fire. His valiant and inspiring leadership was largely responsible for reorganization of troops ashore on beaches immediately to the left (north) of Cape Torokina. Lieutenant Colonel McCaffery

MOPPING UP JAPANESE BUNKERS, two wary Marines of the 3d Regiment help to make Cape Torokina safe for democracy.

died aboard the U.S.S. George Clymer as a result of his wounds, but the inspiration which he had given his men, and the high esteem in which he was held, lived on.32

On the left (north) flank of the beachhead, the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, and the 9th Marines landed against opposition not quite so formidable as that offered by the Japanese, but of a nature to make the landing difficult by any means. Here the beach was steep; so much so that landing boats could not beach along the length of keel. Here jungle grew to the water's edge, and surf was extremely rough: These natural obstacles combined with lack of experience on the part of coxswains caused many landing boats to broach to in the surf. Before the 3d Marines and the Raiders had secured their beaches in the vicinity of Cape Torokina, in order that alternate beaches could be assigned to boats originally assigned in the 9th Marines' sector, 64 LCVP's and 22 LCM (3)'s had broached and stranded. This loss in landing craft resulted in unloading difficulties later.33 Despite this, the 9th Marines quickly made their way ashore, established defensive positions as ordered, and despatched a strong combat patrol to the Laruma River mouth to protect the Division right flank.

On Puruata Island, the 3d Battalion, 2d Raiders,

THIS JAPANESE 75 MM CANNON PLAYED HAVOC with assault waves of the 3d Marines, sinking four landing craft and damaging ten before it was silenced by Sergeant Robert A. Owens, posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his feat.

SERGEANT ROBERT A. OWENS, who posthumously won the Medal of Honor for singlehandedly assaulting and silencing, at the cost of his life, the Japanese 75 mm gun which brought down such destructive fire on 3d Marines landing craft from Cape Torokina.met stiff opposition in the form of Japanese riflemen and machine-gunners in well-concealed pill-boxes, covered by riflemen in rifle pits and trees. The terrain was overgrown by heavy brush and afforded poor visibility. This opposition did not deter the Raiders, however, and individual combat training previously received now stood them in good stead. Throughout D-day and part of the next, the Raiders combed the island and finally succeeded in locating and reducing all opposition. By noon of D plus one day, resistance on Puruata Island had ceased. There were no prisoners.34

The machine-guns on the western tip of the island which had caused such disorganization among landing boats were taken before the first day was over. The Raiders had done their job well.

More than half the leading force--between seven and eight thousand troops--had gotten ashore in the first trip of the boats and had gained footholds on the beaches before interference by Japanese air forces became threatening.

At 0730 large numbers of approaching enemy planes were picked up by radar. Fighter cover succceeded in breaking up most of the Japanese formations, but about 12 Val dive-bombers were able to break through and attack the transports, fortunately, however, only killing two men, and wounding five others in the Wadsworth. During this period, enemy fighting planes ineffectually strafed the beaches but inflicted few casualties since shore party personnel had dug slit trenches immediately upon landing.

Several serious attempts to attack our ships, however, were made by the Japanese within the next few hours. On one occasion, for example, a flight of four Marines fighters from VMF-21535 was patrolling 13,000 feet above Cape Torokina, when six enemy planes were observed approaching our beachhead at 10,000 feet. Each Marine pilot jumped one enemy. After a brief melee, only one Japanese plane was left to streak homeward and one Marine F4U--that piloted by Lieutenant Hanson--was in the water.36 Such interceptions were repeated a number of times throughout the day, and although the ships' antiaircraft fire was ineffective, the fine Marine fighter cover prevented effective enemy air attacks.37

Most serious consequence of these air attacks, however, was the resultant delay in unloading, for twice during the day all ships were required to withdraw from the transport area for defensive maneuvers. Equipment and supplies had been reduced to approximately 500 tons per ship,

SURF WAS EXTREMELY ROUGH AND MANY BOATS BROACHED TO on the 9th Marines' beaches. Reading from left to right in background, lie Cape Torokina, Torokina Island, and Puruata Island.and five hours was the time estimated for unloading. Interruption by air attacks caused certain misgivings with regard to a supply the future of which at that moment was by no means assured. But four transports, which had not finished their task, were able to return to the area on the morning of 2 November, and complete discharge of cargo without further difficulty or delay.38

To add to unloading difficulties, the high attrition of landing craft due to enemy action and surf, reduced the number of boats available for movement of supplies. Coupled with this was the fact that the shore parties unloading on the beach, were taken under fire. As the heavy surf took toll of many boats, intervening shoals prevented the salvage tug, U.S.S. Sioux, from proceeding to assist stranded craft. To make matters worse, it was necessary to abandon beaches on the left because of surf, so ships assigned to those beaches had to shift to new stations.39

Gunnery performance of several fire-support ships left much to be desired when firing on shore targets. Some ships fired short for almost five minutes, with all salvos landing in the water. When finally on target, however, our gunfire was helpful in the initial landing. It must be said, however, that the nature of the terrain was such that effective support was difficult, and shells frequently detonated against trees before they reached their targets.40

Debarkation plans had called for the landing of engineer and anti-aircraft artillery organizations from Task Unit C on beaches within the 3d Marines' sector. Despite great difficulties, antiaircraft defenses were established on the beaches well before the debarkation of equipment and supplies was completed.

On Cape Torokina, as bunker after bunker

fell to the assault of squads and platoons, control was gradually reestablished over the separate battalions; and the advance then begun had by evening successfully terminated in occupation of the proposed initial beachhead line.41

With the fanning out of the first patrols, it became evident that, with the exception of two avenues of approach to Cape Torokina, the 3d Marine Division was hemmed in by swamp and the most dense and rugged jungle that Marines had ever seen. With each battalion on its final objective for the first day, it was only by exceptional effort on the part of communication personnel that even lateral command lines between various teams could be laid before dark. Patrols from the 2d Raider Battalion and from the 1st and 2d Battalions, 3d Marines, pushing through swamp and tangles that held their advance to a few dozen yards an hour, could not make contact. To plug gaps and close possible avenues of approach of Japanese reinforcements which, from documents discovered on bodies of dead in the bunkers, were known to be north of Piva Village, Company E, 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, and Company L, 3d Raider Battalion, were shifted to the Cape Torokina sector and put into position to cover the flank and rear of the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, now nearly 1000 yards from its beach.42

In the meanwhile, the 2d Raider Battalion, which had been assigned the mission of establishing

MOPPING UP ON TOROKINA ISLAND, a platoon of the 2d Raider Battalion finds the going tough, despite the fact that only seven Japanese garrisoned the labyrinthine jungles of the tough little island.

Map 5

Situation, End of D-Day

Cape Torokina

1 Nov 1943a roadblock across the trail to the northeast into the Cape Torokina area before the Japanese could determine a course of action, was securely established. This prevented Japanese forces from having access to the area. The expected counterattack from this vicinity never materialized. In the course of this action the Raiders captured a wounded Japanese Sergeant Major, first prisoner taken in the course of the operation.43

On the day of the landing, the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, had been the right battalion of its regiment. On 2 and 3 November the 1st and 2d Battalions were moved in succession to the right (east) flank of the perimeter. This left the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, on the extreme left flank, still in the same area it had occupied upon landing. Consequently, Lieutenant Colonel Walter Asmuth, Jr., commanding the battalion, curved his left flank back to the sea. Late in the day on 3 November, the battalion was attached to the 3d Marines, which (less 1st Battalion) had been moved from the right to the left sector. Meanwhile the 2d and 3d Battalions, 3d Marines, had begun an advance inland through the swamps.

The line of advance of the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines, was generally to the north to enable it to maintain contact with the Raiders on the right; for this purpose Company A, 3d Marines, was attached to the 2d Battalion from 6 to 11 November. General route of the 3d Battalion was north, then east along the perimeter of the Division beachhead; the 3d Battalion was assigned the mission of locating the route of a lateral road from right to left flank.44

Unloading supplies onto the beachhead of the 3d Marine Division and subsequent distribution of those supplies to beach dumps was a major task on D-day and those immediately following. All transports and cargo vessels supplied personnel to assist in this unloading. Each of the eight APA's furnished a complete shore party, from among troops aboard, consisting of approximately 550 officers and men. Of these, 120 worked unloading

THE 9TH MARINES SHIFTING POSITIONS on the afternoon of D-Day. Men of the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, moving eastward to new areas due to the unsuitability of the beaches, and because of expected enemy resistance in that direction.the ship itself, 60 were boat riders, and 200 were used on the beach with sole duty of unloading cargo from boats. Remaining personnel were used for shore party headquarters, pioneer work, vehicle drivers, dump supervisors, communicators, medical personnel, beach party personnel, and for work at the dumps created.

It had been planned to have the AKA's furnish 120 men for work in holds, 50 men to ride boats to and from shore, and 200 men to work on the beach, unloading cargo from boats as they landed. Only 350 officers and men were available to each AKA, however, it therefore became necessary to make up the difference by drawing men from the APA's. This drain upon personnel embarked in the APA's was felt principally by combatant units.

Used in initial stages of the operation as working parties to assist shore parties was a large percentage of personnel of the 12th Marines. One battery of this regiment was to be landed with each battalion of the 3d and 9th Marines. Since many artillerymen were not released from shore party duties until 4 November, several batteries could not be placed in operation until that date.

In addition to 12th Marines personnel, men from H & S Company, 19th Marines (whose regular duties consisted of reconnoitering for orientation of high and low ground areas, in order to disseminate terrain information rapidly for tactical, engineer, and dispersal purposes), were used until 3 November by the shore party. Other elements of the 19th Marines were assigned completely, with the exception of a few demolition personnel, and were also engaged in shore party activity until 9 November. Naval Construction Battalions augmented shore parties and were not released until 3 November to begin road construction. Some personnel from companies of the 3d Medical Battalion were held with shore parties until 11 November.

Other units used in shore party work and in

establishment of supply dumps were assigned regularly to the task. These included elements of the 3d Service Battalion, 3d Motor Transport Battalion, 3d Amphibious Tractor Battalion, and 3d Medical Battalion. Also included during D-Day landings were elements of Division Special Troops: Headquarters Battalion (Headquarters, Military Police, and Signal Companies); Special Weapons Battalion; and parts of the Tank Battalion.

Three platoons of the Special Weapons Battalion landed on D-Day, the remainder coming in on 6 November. The entire Battalion was attached for operational purposes to the 3d Defense Battalion. Those elements of the Tank Battalion which landed, acted for the first several days as scouts and reconnoitered terrain over which they would be required to fight.

In spite of the tie-up during D-Day, the 3d Defense Battalion brought ashore on beaches of the 3d Marines most of their bulky anti-aicraft equipment, and managed to establish antiaircraft defenses on 1 November before unloading of equipment and supplies was completed. Battery D (90mm), however, landed on D-Day as infantry and did not land its guns until the following day.

Although the landings had been made with comparatively small loss in men and material, some confusion still existed on several beaches due to circumstances which had arisen after boats had left their line of departure. The impossibility of landing supplies and equipment on the three western beaches, forced boats originally destined for them to discharge at points farther east. Despite this, the job of unloading was completed.

Daylight hours of 2 and 3 November were devoted to sending out patrols to flanks and front for the purpose of insuring security and reconnaissance; in establishing beach defenses; and in reinforcing and improving defenses of the Cape Torokina sector. On 3 November, after a ten minute preparation by a 12th Marines 75mm Pack Howitzer battery and automatic weapons of the 3d Defense Battalion, the 3d Raider Battalion sent a combat patrol consisting of two platoons from its Demolition Company to Torokina Island, where a small but determined band of Japanese had harassed Cape Torokina and Puruata beaches with machine-guns for two days. No Japanese were found. Initial resistance to our landing had come to an end.45

During the first three days, 192 Japanese dead were buried in all sectors.46 The stoutly-held defenses around Cape Torokina had been reduced with facility, at a cost of 78 killed and 104 wounded. The beachhead was firmly established to a depth of about 2000 yards.47

Naval Battle of 1-2 November

The Japanese wasted no time in reacting to the landing on Bougainville. As soon as they could divine U.S. intentions in the Bougainville area, the enemy immediately began to assemble available naval forces in the vicinity of Rabaul. Returning Allied pilots and coastwatchers reported that at least two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, 10 destroyers, and other light units had been sighted in that area. It appeared that the Japanese were going to make a major effort on the surface.48

The only U.S. Navy striking force available in this area was Admiral Merrill's task force, which had bombarded the Buka-Bonis and Shortland areas in preparation for initial landings. Immediately after the Shortlands bombardment, this force had refueled and returned to the Cape Torokina region to protect landing forces from surface attack, and to cover retirement of the transports.49 Admiral Merrill at this time had with him under his command four light cruisers and eight destroyers.50

Very early on the morning of 2 November the Merrill Task Force was in position off the entrance to Empress Augusta Bay to intercept enemy surface forces reported in the vicinity and which appeared to be approaching Cape Torokina. A new moon afforded little light, but occasional flashes of heat lightning silhouetted the ships. Although the night was dark and cloudy, a light southwest wind sometimes puffed the clouds away to reveal patches of clear sky.51

Rear Admiral S. Omori, sailing from Rabaul in the heavy cruiser Myoko, with the heavy cruisers Haguro and Agano, the light cruiser Sendai, and six destroyers, was Admiral Merrill's opponent.52

At about 0027, radar contact with the Japanese force was made and our destroyers were ordered to attack with torpedoes. Since the Japanese force was divided into three groups and was spread over a wide area, it was impossible to keep the entire force simultaneously on the radar screens. In addition to this difficulty, certain units of the U.S. task force were inexperienced and were required to conduct a difficult maneuver under very adverse conditions.53 At about 0230, nevertheless, in an area roughly 45 miles west northwest of Empress Augusta Bay, U.S. destroyers delivered the initial torpedo attack. In the ensuing action, the Sendai and the destroyer Hatsukaze were sunk while the Haguro, the Myoko and the destroyer Shiratsuyu were damaged. On the United States side, the Foote was hit in the stern by a torpedo, and the Spence and the light cruiser Denver received minor damage from gunfire. Throughout the engagement the Japanese commander had difficulty in locating our forces despite the fact that star shells and aircraft flares were employed repeatedly. Although the night was dark and overcast, Admiral Merrill employed smoke to screen his maneuvers, thus hampering Japanese efforts at illumination. Admiral Omori broke off action because the radar-controlled fire of the U.S. ships was vastly more effective than his own optically-controlled weapons, and because he had no accurate estimate of the size of the opposing American force. In addition to this, he rightly feared being in position where American planes could find him at daylight.54

As a result of this battle, Task Force Merrill enjoyed the satisfaction of defeating and turning back a strong Japanese force and thereby saved the Bougainville transports and landing forces from what might well have been disaster.

By nightfall 3 November, the beachhead on Bougainville had in any case been firmly established, and all immediate objectives secured. Construction of an airstrip and an advance naval base began.

Establishment of the Perimeter

Establishment of the perimeter, which formed the second phase of the operation, took place largely within the month of November. Five major actions (one defensive and four offensive) were fought during this period, while non-combatant activity included the building of a network of roads, construction of a fighter strip, survey for a bomber field, location of dumps and other problems of support. Japanese opposition was for the time being less onerous than were natural obstacles, but, despite severe handicaps, communications functioned smoothly and satisfactory progress was made on the fighter strip during the month.

The second phase defined itself by the steps of progression leading from seizure of a foothold on Cape Torokina to establishment of a perimeter within which, by 30 November, the various objectives--fighter strip, projected bomber field and advance naval base--were defended by well-anchored lines.

In the first several days intelligence reports indicated only scattered enemy groups facing the right flank Marine forces on a line running from the Koromokina River to the vicinity of the Piva. Surprise, which had rolled over the meager Japanese defenses, was now exploited with speed.

The Japanese could offer nothing more serious than patrol action and sniper infiltration during the first six days after the beachhead had been secured.

For a considerable period, in fact, there was no indication that the enemy was aware of the true objective of the operation, that is, to establish and maintain a beachhead on Bougainville within which fighter and bomber fields could be built and an advance naval base established. That the Japanese had stationed only 300 troops in the vicinity of Cape Torokina, though aware of the possibility of a landing there, would indicate that they had not taken our threat seriously. It may be that, knowing the beach and terrain conditions rather intimately due to months of association, the enemy felt that we would never attempt a landing in that area, or that, if we did, then the operation would surely fail.

From an enemy prisoner and captured documents, it was determined that the Japanese had anticipated a landing at Cape Torokina on or about 30 October, but since his defenses were made up of only approximately 300 men and one 75mm gun, he could not have considered the threat except in the most casual expectancy. There was also evidence that the enemy considered a main landing more likely in lower Empress Augusta Bay with Motupena Point and the Jaba River as the prime objectives. Much stronger defenses against landing operations were organized at those points.55

There were several courses of action that he might pursue: He could make counterlandings on either flank with movement of troops in small craft from Buka passage or the Kahili area, supplemented by movements in destroyers from Rabaul, or he could attack overland with forces in southern Bougainville. He might prevent occupation of the ground selected for the airfields. By shelling and air bombardment he might impede our shipping and the extension of our defensive positions.

But no course whatever was pressed home with sufficient determination to put in jeopardy ground we had won. The chief enemy threat, however, seemed mostly likely to emanate from the south against our right flank or center.56 Nevertheless, the counterlanding at Atsinima Bay, which led to the Koromokina lagoon engagement, and air harrassment, almost exclusively by night, were the only tangible efforts mounted by the Japanese from among the many capabilities which we adjudged to be theirs during the early days of the beachhead.

Physical difficulties within the Bougainville beachhead were even greater than had been expected from reconnaissance and observation made prior to the landings. No roads existed in the area, and vehicular communication could be effected only along the narrow strip of beach where surf sometimes ran waist deep.

On the left flank some 10,000 yards west of Cape Torokina was the Laruma River, at places fairly wide and for the most part seeking its way to the sea with directness. On the right flank was the Piva, a tortured stream which writhed like a snake as it sought an outlet through jungle lowlands, making frequent bends which gave the Japanese excellent vantage points. To the center, the plume of smoke and glow of the active volcano, Mount Bagana, served as a guide, beckoning our troops to the serrated ridges of the Crown Prince mountain range.

Koromokina Lagoon

When it became apparent immediately after the D-Day landing that the Japanese did not intend to offer resistance on the left (west) flank of the beachhead, General Turnage decided to have the 3d and 9th Marines exchange sectors, for the 3d had been more heavily engaged and had suffered numerous casualties, particularly on D-Day.

To this end, as we have seen, on 2 and 3 November, the 1st and 2d Battalions, 9th Marines, were moved to the right (east) sector, while the 3d Marines less 1st Battalion (attached to the 9th Marines in a reserve position in the right sector), moved to the left (west). The 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, remained in position on the extreme left of the perimeter with its flank resting

on the sea; this battalion was attached to the 3d Marines.

At 1800, 3 November, responsibility for each sector shifted to the newly occupying regiments. The 2d Raider Battalion was assigned the road block on the Piva Trail, and the 3d Raider Battalion constituted the Corps Reserve.

After reduction of Japanese resistance to the initial landing, enemy activity was confined on 4, 5, and 6 November to patrol activity against the flanks of our positions. Thirteen Japanese were killed.57 Marines in the meantime were not inactive. Not only were extensive patrols sent out, but positions were improved and forces reorganized for further fighting. In addition, units

3D DEFENSE BATTALION ANTIAIRCRAFT gunners deliver trial fire in order to obtain best ballistic data for the 90mm gun which has just been set up overlooking Cape Torokina.

able to do so attempted to make conditions livable, particularly in the matter of galleys, in order that hot food might be served.58

The 3d Marine Division and its attached units now began to feel for the enemy as they sought to widen the beachhead; the second phase of the operation thus began.

On 6 November, the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines reverted to control of its parent regiment and was moved as regimental reserve to positions east of the Koromokina River; the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, which had arrived on Bougainville on that day, was attached to the 9th Marines and was assigned a reserve position of Puruata Island.59 Before the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, could be moved to the right sector, however, events transpired which delayed their move still longer.

A few minutes before 0600 on the morning of 7 November, four Japanese destroyers hove to in Atsinima Bay, having just made the run from Rabaul. In the half-light of dawn, a force of about 475 Japanese troops debarked into 21 boats and barges, which made their way to shore.60 Although observed from positions occupied by an anti-tank platoon on the beach in the west sector, no positive identification of the boats was made until it was too late to take action.61 Fortunately, because the enemy landed over so wide a front that his full strength could not be assembled quickly, he had to decide whether to lose the initial advantage of initiative, or to attack with but a portion of his force. Characteristically, he chose to attack at once.62

Company K, 9th Marines (Captain William K. Crawford), with the 3d Platoon, 9th Marines Weapons Company (First Lieutenant Robert S. Sullivan) attached, was holding the extreme left flank of the Division beachhead. A combat outpost had been set up in front of this position which consisted of the 2d Platoon, Company M with a platoon of Company D, 3d Tank Battalion (Scouts) attached.63 This outpost was dug in between swamp and sea, astride the main avenue of approach to our lines from the west. In the meanwhile, a reconnaissance patrol consisting of one platoon of Company K, 9th Marines, was operating along the upper reaches of the Laruma River.

Two Japanese boats, containing an estimated 40 to 50 men, were observed to land with the initial wave only about 400 yards to the west of the U.S. perimeter, in rear of the 9th Marines' combat outpost. This enemy group immediately launched an attack on the positions occupied by the 9th Marines Weapons Platoon. Failing to penetrate the position, the enemy retired into the swamp to regroup for further attack.64

Lieutenant Colonel Walter Asmuth, Jr., commanding the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, immediately ordered Company K to attack, and called for artillery and mortar support. The attack was launched at 0820, and after having moved only 150 yards, the left assault platoon encountered Japanese who were already digging positions facing the Division main line of resistance. Heavy firing with machine-guns and rifles began, and Company K's left platoon was soon pinned down. The center and right platoons attempted an envelopment in order to attack toward the south, but progress was extremely slow because of dense jungle and heavy swamp. By this time, however, the Japanese had already constructed effective fox-holes and made the most of natural concealment. Furthermore, the enemy was able to take advantage of fox-holes abandoned by the 1st and 2d Battalions, 9th Marines, upon the regrouping of forces several days before. Eventually, therefore, the two enveloping platoons were also pinned down by enemy fire. Since Japanese reinforcements were coming ashore from boats landing

INFIGHTING AT KOROMOKINA LAGOON took place when Japanese troops of the 54th Infantry came down from Rabaul and attempted a counterlanding against the 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, on 7 November.down the beach, additional troops had to be called.65

At 1315 the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, was ordered into the attack. Company B was in assault, while Company C was echeloned to the right rear. This battalion was to move in left of Company K, 9th Marines. As soon as Company B, 3d Marines, was in position, Company K, which by this time had lost five killed and 13 wounded, was withdrawn. By this time the enemy numbered 200 or more. The attack was now in the hands of the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines.66

The character of the fighting on 7 November was hand-to-hand, shot for shot, grenade for grenade. The enemy was dug in; our troops were forced to advance upon emplacements which, five yards away, were not even suspected. It was in this engagement that Sergeant Herbert J. Thomas of Company B, 3d Marines, gave his life in an act of heroism which earned him, posthumously, the Medal of Honor. As his squad advanced through the jungle undergrowth, it was held up by Japanese machine-gun fire. With the intention of knocking out a machine-gun with a grenade, he placed his men in a position to rush in after he had done his work. Sergeant Thomas hurled his grenade, but his comrades froze when they saw it catch in some vines and fall back among them. Thomas instantly threw himself upon the grenade to smother the explosion with his body, and was killed a few seconds later.

Among officers, the hero of the day was

Captain Gordon Warner, Company B commander, who lost his leg as a result of this action. With a helmet full of grenades in his hand, Warner personally led a tank from position to position in order to destroy six machine-gun posts. Warner shouted defiance at the enemy in Japanese,67 ordering them to fix bayonets and charge; they dutifully obeyed, only to be cut down by Marine rifle fire. By building up a firing line, Warner obtained fire superiority, and consequently prevented infiltration of Marine lines. Captain Warner was subsequently awarded the Navy Cross.68

As the fight in front of the perimeter was developing, the patrol from Company K, 9th Marines, which had been reconnoitering the vicinity of the Laruma River, made contact with Japanese troops near the river mouth. A short fire-fight broke out, and rather than become involved with much stronger forces, the patrol leader, Second Lieutenant Orville L. Freeman, wisely decided to move upstream a short distance, then turn east and head for our lines. Every several hundred yards of movement, the Marines would set up an ambush and fire at the Japanese who were attempting to follow. This patrol returned to our lines about 30 hours later, having suffered loss of one killed and one wounded (Lieutenant Freeman); it had accounted for a minimum of three counted Japanese dead,69 plus, in all probability, other casualties during its series of ambushes.

At the same time, a Japanese force estimated at company strength struck the combat outpost from positions near the mouth of the Laruma. Although the outpost had an artillery forward observer with it, at this juncture his radio failed to function. Consequently the observer had to make his way individually back to our perimeter, there to telephone his fire mission to his battery.

SERGEANT HERBERT J. THOMAS was awarded the Medal of Honor at Koromokina Lagoon for his heroism in smothering a grenade's explosion with his own body.The concentration fell exactly as called, but the outpost continued to be hard pressed. Shortly afterwards, the officer in command of the outpost determined to withdraw to positions within the perimeter, but in so doing encountered the Japanese who had landed between the outpost and the perimeter. The Marines thus found themselves with their backs to the sea, hemmed in by Japanese on three sides. Lieutenant Frank H. Nolander, USNR, was ordered to take two tank lighters to the beach where the outpost was engaged, embark the men and withdraw them. This Nolander did, so that by 1430 he was able to report "60 men were evacuated from the Laruma River outpost without incident".70

By nightfall the situation had clarified. The 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, was able to establish an entirely new set of lines forward of those which

Map 6

Battle of Koromokina Lagoon

7-8 Nov 1943had originally marked the perimeter.71 The 9th Marines combat outpost had been safely evacuated from its precarious position, and the platoon of Company K, 9th Marines, which had been patrolling along the Laruma River, had retired into the swamp and was even now making its way back to safety. Just as darkness set in, however, the 1st Platoon, Company B, 3d Marines, became cut off from the main body.

Platoon Sergeant Clifton Carter, who at that time was in command, set up an all-around defense and prepared to wait for daylight before trying to contact with the adjacent units. With one light machine-gun, Browning Automatic Rifles, and hand grenades, Carter and his men held this exposed position throughout the night, returning to the U.S. lines at daybreak. The success of his action was not a fluke, for the men had received thorough training in night patrols during the stay of the 3d Marines on Samoa, and Carter's platoon was particularly well-qualified in that type of work.72

Company C, 3d Marines, which had been held up by the swamp during the attack, now was able to tie in with Company B, so that the Marines now presented a single front to all enemy attempts to penetrate the perimeter during the night. Company officers in the front lines prepared and coordinated the artillery call fires which were shot during the night. To rearward regimental and battalion commanders planned an attack for the next day, despite the fact that some Japanese, trapped by the solid lines of Marines, operated behind our front. Artillery prevented additional enemy troops from moving up to attack.73

In the late hours of 7 November a coordinated attack was planned by the Commanding Officer, 3d Marines. Action began early on 8 November, with a 20-minute preparation by five batteries of artillery assisted by machine-guns, mortars and anti-tank weapons.74 The 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, (Lieutenant Colonel Ernest W. Fry, Jr.), which early in the fighting had been moved into the sector of the 3d Marines and attached thereto, passed through the 1st Battalion, 3d Marines, and attacked with light tanks on a two-company front, A on the right, B on the left, with the reserve company to the right rear.75 There was not opposition to this advance.

A tomb-like stillness settled over the jungle after the artillery preparation lifted, for over 300 enemy had been killed in an area 300 yards in width to at least 600 yards in depth.76 Even though they advanced to a lagoon some 1500 yards west of the Koromokina River, the 21st Marines did not again make contact with enemy in this area until 13 November.

The Battle of Koromokina Lagoon had been won.

On 9 November, to insure that the Koromokina Lagoon-Laruma River area would be cleared of any possible concentrations of survivors, a dive bomber strike bombarded and strafed beaches, jungles, and swamps from the western edge of the perimeter to the Laruma River and 300 yards inland. Patrols later found bodies of many Japanese apparently caught by the strike as they returned to the area from the refuge they had taken in the back country.77

The air strike of 9 November ended enemy activity on the west. At noon on that day the sector and control of the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, passed to the 37th Infantry Division, leading elements of which had now arrived. The 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, reverted to the 9th Marines and was shifted to the Cape Torokina sector. The 1st Battalion, 3d Marines returned to regimental reserve.78

From prisoners of war and captured documents, it was learned that General Imamura, Japanese area commander at Rabaul, had planned to put about 3,000 men ashore in three echelons, and the force which landed on 7 November was only the first of these. This unit had the mission of landing just beyond our beachhead, push inland, get behind the perimeter defense,

Map 7

Torokina Beachhead

Evening of 7 Nov 1943and engage in guerilla warfare. While they conducted this diversion in the west and north, the Japanese 23d Infantry Regiment, supported by field artillery, its Regimental Gun Company, and a Light Trench Mortar Company, was to attack our right (east) flank with two battalions at about 0600 on 9 November. This regiment was to attack from an assembly area near Peko, northeast of Mopara, and effect a junction with the force on our left flank in vicinity of Piva No. 2. Another force of undetermined size was to make a landing immediately west of the Torokina River, while a platoon of 40 men was to land just east of the river. The Japanese believed our beachhead to be farther east than it actually was, and had estimated our strength to be about five to ten thousand troops.

The first and only echelon to land was wiped out.

Marine losses for the battle were 17 killed and 30 wounded; 377 Japanese bodies were counted on the field.79

Thus the enemy's first serious effort to retake the beachhead was defeated by the vigorous action of the 3d Marine Division, whenever and wherever contact was made. As our troops pushed through tangled vines, suddenly, sometimes at their very feet, they would find a Japanese soldier hidden in a deep, well-concealed foxhole. Their attention would be drawn only by the crack of his machine-gun or rifle as he fired. That our losses were not more severe was due in large measure to poor Japanese marksmanship, although the enemy was well armed and the terrain suited him perfectly.80

Piva Road Block

A part of the mission assigned to the 2d Raider Regiment for D-Day was established of a road block astride the Buretoni Mission-Piva Trail, which led from Beach YELLOW One inland, in order to deny the enemy use of this trail, the main

route of access to our position from the east. Company M, commanded by Captain Francis O. Cunningham, was initially assigned this duty. Cunningham was ordered to assemble immediately upon landing in order to advance along the trail for a distance of about 1500 yards, where he was to set up the road block.81

Although Company M killed several stray Japanese, it met no organized resistance and was able in due course, to set up the road block about 300 yards west of the Piva-Numa Numa Trail junction without difficulty.82

In the meantime the 2d Raider Battalion had advanced to the O-2 line, about 1200 yards inland from the beach. On 3 November, at 1520, Company E relieved Company M on the road block. The following day the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, relieved the 2d Raider Regiment on the O-2 line, and the 3d Raider Battalion reverted to its parent unit, having accomplished its task of clearing Puruata and Torokina Islands for the 9th Marines. The 2d Raider Regiment now was attached to the 9th Marines but retained responsibility for the road block, furnishing Company E for this duty.83

Until this time there had been little or no resistance, but now the Japanese sent in reinforcements. These were larger men, in better physical condition and better equipped than enemy previously seen.84 At 2200 and again at 2330 on 5 November, Company E was attacked in its positions by an undetermined number of Japanese, some of whom were able to filter through our lines. Finally at 1430, 7 November, coincident with the counterlanding at Koromokina, an assault was made on the road block, now held by Company H. As the tempo of the action increased, at 1500, Company G was sent forward to reinforce Company H. Mortars of the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines fired heavy concentrations in support of troops on the road block, and at 1550 the enemy broke off contact.85 After this fight, Company H was withdrawn from the

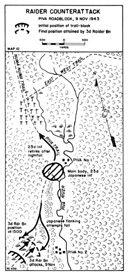

Map 9

Fight at Piva Roadblock

5-7 Nov 1943road block; Company G remained. Japanese were now observed digging in west of Piva Village, in the meanwhile harassing Company G throughout the night with mortar fire.86

Early in the morning of 8 November, in order

MARINE WAR DOG assists in patrolling up Mission Trail.to frustrate any further Japanese attempt to attack the road block, Company M, 3d Raider Battalion, was sent there to take up positions behind Company H, which was once again responsible for defense of the installation. At 0730 a force consisting of elements of the 1st and 3d Battalions, 23d Japanese Infantry Regiment, struck following a four-hour mortar preparation.87 The defending Marines held until 1400, when Companies E and F effected a passage of lines and launched a counterattack which forced the Japanese back a short distance. At the same time, the 4th Platoon, Weapons Company, 9th Marines, supported by two tanks, was ordered to reinforce the attack, but, due to thick jungle and swampy trails, half-tracks and tanks were able to do nothing more than evacuate wounded who by now numbered 12.88

Japanese resistance stiffened markedly, and the Raiders' attack bogged down about 1600, whereupon they were withdrawn to a bivouac area within the perimeter for the night.89

During the night General Turnage ordered Colonel Edward A. Craig, commanding the 9th Marines, to plan an attack next day which would clear the Japanese from the area in front of the road block.90 In the meantime Company I, 3d Raider Battalion, relieved Company H on the position; the latter retired to the 2d Raider Battalion bivouac.

For his attack, Colonel Craig decided to use elements of the 2d Raider Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley, since that regiment was more familiar with the terrain in the vicinity. He ordered Shapley to attack on a two-company front at 0800 following an artillery preparation, with the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, a section of tanks, and the 4th Platoon, Weapons Company, 9th Marines, in support.91

Responsibility for the attack was further passed from Shapley to Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, commanding the 3d Raider Battalion.92

According to plan, at 0620 on 9 November, Companies L and F of the 2d Raider Regiment deployed to the left and right of the trail behind the road block, now being defended by Companies M and I.93

From 0730 to 0800, the 1st Battalion, 12th Marines, fired an artillery preparation, during which Colonel Craig went forward to coordinate the attack. At 0800 Companies L and F passed through the lines of Companies M and I, and

Map 8

Piva Action

Nov 1943began a slow advance through the jungle at the rate of about 100 yards an hour.94 In the meantime, while our troops were moving into position to launch the attack, the Japanese attempted several attacks on the right of our road block causing one platoon of Company F to be held up so that contact was lost between the various platoons of that company. This contact was not effectively regained for the duration of the attack. By 0930 the attack had progressed only about 40 to 50 yards. A heavy fire-fight was in progress, the Japanese resisting our advance with light machine-guns and "knee mortars". Since flanking maneuver was inhibited by swamp, the assault necessarily had to be frontal. The Japanese were screeching defiance, while Marines yelled back.95

By 1030, Company F had become so confused due to internal lack of contact, that Company I was sent in to relieve it. Almost immediately upon resuming the attack, Company I reported that the Japanese were attempting to move around the right flank of our assault. As a countermeasure, Colonel Craig deployed the Weapons Company, 9th Marines, to the right rear of Company I. This stopped the Japanese threat. At approximately 1130 Companies I and L drifted apart, so one of the two support platoons of Company M was sent into the gap in order that the advance would not be held up. In face of stubborn opposition, the advance continued slowly, until, quite suddenly at 1230, for reasons still obscure, enemy resistance collapsed.96

The advance now became quite rapid, and by 1500 Marines had reached the junction of the Piva and Numa Numa Trails. Since no enemy had been encountered for a period of more than 70 minutes, assault elements were ordered to dig in and consolidate the ground so recently won with such difficulty.97 Local security patrols were sent out about 200 yards to the front and upon returning these reported that no Japanese had been contacted, but that there was a large, empty

Map 10

Raider Counterattack

Piva Roadblock

9 Nov 1943bivouac area about 300 yards up Numa Numa Trail. At about 1720 several Japanese stragglers were reported withdrawing along the Numa Numa Trail, and at 1815 a defensive barrage was fired on three sides of the Marine position. This seems effectively to have discouraged the Japanese,

APPROACHING PIVA ROAD BLOCK, Marines of the 2d Raider Battalion keep clear of the trail.for there was no further enemy activity that night. Although the Marines lost 12 killed and 30 wounded as a result of this operation, over 100 Japanese dead were counted on the field.

That night Colonel Craig once again planned an attack for the following day. This time he decided to have the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, pass through the defensive positions which had been set up at the trail junction, with the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines in support. The 3d Raider Battalion was assigned the mission of protecting the left (northwest) flank of the attack. The attack was to be preceded by a 15-minute artillery preparation followed by a five-minute bombing and strafing attack by VMTB-143.98

As planned, the planes (12 TBF's) arrived on station at 0915.99 The artillery preparation, however, had to be held up for about ten minutes in order that a reconnaissance patrol of the 2d Raider Regiment could withdraw from the target area.100 Consequently the time of attack was postponed until 0945. The artillery fired its preparation, and marked the target area for the planes with smoke shells. Front lines were marked with colored smoke. Planes acknowledged the target area at 0920 and at 0945, when artillery lifted, made their run. Simultaneously, the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, jumped off in attack. There was no resistance, for the enemy had evacuated his positions leaving equipment, ammunition, and even rifles behind. Piva Village was secured by 1100, and the 2d Battalion, 9th Marines, organized an all-around defense and prepared to hold the village against any attack. The 1st Battalion, 9th Marines moved north on the Numa Numa Trail, about 250 yards from the junction, and dug in astride that trail. The following day the line "A

MARINES AT CLOSE QUARTERS with Japanese of the 23d Infantry Regiment during the Piva Road-Block action, 9 November 1943.to E" was established and the battle for the Piva Road Block was completed.101

The artillery barrage which preceded the attack of 9 November was most effective in the Japanese rear areas. Nonetheless, in areas immediately to the front of the road block, although the barrage had been placed within 250 yards of our lines, it was relatively ineffective. This was due to the fact that during the night the Japanese had crept to positions within 25 yards of the road block, and during the barrage had remained quiet. Consequently, when the artillery lifted and the Marines jumped off, they were met by a sudden, intense volume of close-range rifle and automatic weapons fire.

It was later learned that the Japanese were making an all-out effort to break through our lines, believing that their attack was coordinated with the attack on the left (west) flank of the beachhead. At the Piva road-block, wide flanking movements were denied to the enemy by the difficult terrain on both flanks of the position. The Japanese, however, attempted such a maneuver, first on one flank, then on the other, but on both occasions they were repulsed, and the attacks degenerated into straight frontal assaults on companies deployed to the rear of those in assault.

Japanese attacks were very determined, but, due to the terrain and the disposition of our troops, the enemy was forced to expose himself. This probably accounts for the relatively heavy enemy casualties (over 550 dead) as compared with our own (19 killed and 32 wounded) in that area during the period 5 November to 11 November.102

It was during the engagement of 9 November that Privates First Class Henry Gurke and Donald G. Probst, Company M, 3d Raider Battalion were occupying a two-man foxhole in an advanced outpost. Having located the two Marines,

the Japanese placed it under heavy machine-gun fire followed by a shower of grenade. Two Marines in a nearby foxhole were killed immediately, but Gurke and Probst continued to hold their position. During a lull in the firing, Gurke and Probst discussed the comparative capabilities of the rifle and automatic rifle, the weapons with which they were respectively armed. Both men agreed that the automatic rifle, Probst's weapon, was the more effective for the type of work they were doing. Observing that many grenades were falling close to their position, Gurke told Probst that he would "take it" if a grenade should fall into their hole, in order that Probst could continue in action against the Japanese with his automatic rifle.

The intensity of the Japanese attack increased; a grenade suddenly landed squarely between them. Even though he was aware of the inevitable result, Gurke forcibly thrust Probst aside and flung himself down to smother the explosion, thereby sacrificing his life in order that his companion could carry on the fight. Gurke was awarded, posthumously, the Medal of Honor. Inspired by Gurke's courageous deed, Probst, although wounded, kept his automatic rifle in action and held his position. For his work, Probst was awarded the Silver Star.103

Coconut Grove

In the midst of the action at the Piva Trail road block, on 9 November 1943, Major General Roy S. Geiger relieved General Vandegrift as Commanding General, IMAC, and simultaneously assumed command of Allied forces on

MACHINE-GUN CREW of the 3d Raider Battalion engaging the Japanese enemy from a typical Bougainville foxhole during the Piva Road-Block action, 9 November 1943.

PRIVATE FIRST CLASS HENRY GURKE won the Medal of Honor for intentionally smothering a Japanese grenade in order that his mate, an automatic rifleman might be able to remain in action.Bougainville and the Treasury Islands.104 General Geiger from an advanced command post on Bougainville took direct command of all forces ashore.

Elements of the 37th Infantry Division were now beginning to arrive at Bougainville. The first of these, the 148th Infantry, reinforced, arrived on 8 November and was attached to the 3d Marine Division until 1200, 14 November, when it reverted to the 37th Division. The 129th Infantry, reinforced, arrived on 13 November, while the 145th Infantry, reinforced arrived on 19 November. The 2d and 3d Battalions (both reinforced), 21st Marines arrived on 11 and 17 November respectively.

The 148th Infantry began relief of units (3d Battalion, 9th Marines, and the 3d Marine Regiment) in the left sector on 9 November; this relief was completed the following day. The 3d Battalion, 9th Marines, moved to the right flank of the right sector prior to the attack on 10 November. The 3d Marines moved inland and to the east, thus creating a center sector of the beachhead.105

Main attention of the Corps was now directed to patrolling, development of supply routes through extremely difficult swamp, and extension of the beachhead in both Division sectors to include proposed airfield sites already selected by ground reconnaissance.

As elements of the 37th Division continued to arrive, the beachhead was extended inland with the 37th Division occupying the left (west) flank and the 3d Marine Division occupying the right (east). Extension of the 3d Marine Division beachhead was particularly slow due to:

- Enemy resistance in force throughout the entire Piva River Forks area;

- Extremely swampy ground, unsuitable for continued occupation, located east of the Piva River, south of the East-West Trail; and,

- Great difficulties encountered in road construction and ingress through swamps for supply and evacuation routes. Special care had to be exercised lest forces be advanced beyond our means of maintaining them.106

Only minor clashes marked the operation for several days after the hard fighting in the vicinity of Piva Road block, but meanwhile there was widespread combat and reconnaissance patrolling. Priority for the moment was road-building. Extensive swamps between the Koromokina and Piva Rivers were hindering supply to front lines. Only half-tracks, Athey trailers, and amphibian tractors could traverse the trail which had been

cut through the jungle from Piva River mouth to the vicinity of Piva Number Two (a village along the banks of the Piva River). Beyond that point the Numa Numa Trail was passable.107

Meanwhile, enemy dispositions became more clearly defined. The Japanese were evidently in force up the Piva River, north of a coconut grove along that river near the junction of the Numa Numa and Piva-Popotana Trails. Some Japanese were observed to have taken up positions on the east bank of the Piva, and apparently were contained in an area of about 1,000 yards by 1,000 yards. From those positions they directed both mortar and machine-gun fire into our lines. Furthermore, Marine patrols ascertained that enemy outposts were located on the west bank of the river, scattered through the coconut grove and around the junction of the Numa Numa and East-West Trails.108

Shortly after the occupation of Piva Village, Commander William Painter, CEC, USNR, and a small party of Construction Battalion personnel moved out with a covering infantry patrol to make a reconnaissance for an airfield site. A suitable area was located, well to the north of the perimeter, but Painter, nevertheless, set about cutting two 5,000 foot lanes destined to become landing strips. Painter returned to the Marine positions a day in advance of the combat patrol, which, on 10 November, made contact with a Japanese patrol.

Subsequent patrols up the Piva Trail, beyond the coconut grove near the East-West Trail junction, failed to establish contact with the Japanese. However, due to tremendous difficulties encountered in movement and supply through the swamps, it was impossible to advance the perimeter of the beachhead far enough to cover the proposed airfield site selected by Commander Painter. It was therefore decided to establish a strong outpost, capable of sustaining itself until the lines could be advanced to include it, at the junction of the Numa Numa and East-West Trails, in order to avoid a fight for the airfield site should the Japanese occupy it first.

On the afternoon of 12 November, therefore,

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ROY S. GEIGER, pioneer Naval Aviator and veteran Marine combat commander, both ground and air, assumed command of IMAC on 9 November 1943, and carried through the Bougainville operations of the Corps to their close.General Turnage directed the 21st Marines to send a patrol of company strength up the Numa Numa Trail at 0630 the following day. This patrol was to move up Numa Numa Trail to its junction with the East-West Trail and then reconnoiter each trail for a distance of about 1,000 yards, with a view to establishing a strong outpost in that vicinity in the near future. Company E, 21st Marines (Captain Sidney J. Altman) was originally assigned this mission. During the night however, further orders came from division headquarters to the effect that the patrol should be increased in strength to two companies, with a suitable command group and an artillery forward observer team. The mission was modified in that the outpost at the junction of the East-West and Numa Numa Trails was to be established immediately.109

In view of importance of his assignment, Colonel Evans O. Ames, commanding the 21st Marines, decided to send the entire 2d Battalion; the 3d Division chief-of-staff approved this plan. Accordingly, orders were issued to the 2d Battalion, 21st Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Eustace R. Smoak), to have Company E move out at 0630, 13 November, and proceed to an assembly area in rear of the front line of the 9th Marines, remaining there until the remainder of the Battalion would be able to join it.110

No artillery preparation was planned for the advance of 13 November, an omission which proved costly, for it later came to be recognized as of prime importance against the Japanese system of defense. With their well dug-in, concealed, and covered foxholes, equipped with a high percentage of automatic weapons, in turn covered by equally invisible riflemen in trees and spider-holes, it had become evident that severe losses would be sustained by attacking infantry, regardless of the size of the force, unless attacks were preceded by artillery or mortar preparation or bombing--or better still, by all three.111

On 13 November, Company E cleared its bivouac area at 0630 as planned and proceeded to an assembly area in rear of the 9th Marines' front lines, where it waited further orders. In the meantime, the remainder of the Battalion drew rations, water and ammunition, and waited for arrival of the artillery forward observer party. At 0730 Colonel Robert Blake, 3d Division chief-of-staff, called Colonel Ames, and directed that Company E proceed out the Numa Numa Trail and begin to set up the outpost. Altman led his company through the lines of the

A MARINE FOR THE TIME BEING, Admiral W. F. Halsey is briefed on the situation ashore by the Marine Commanders (left to right), Generals Noble, Geiger, and Turnage.

9th Marines at 0800 and proceeded up the Numa Numa Trail without incident. Suddenly at 1105, when the company had reached a point about 200 yards south of its objective, it was struck by heavy fire coming from a Japanese ambush. Deploying his company as best he could under the circumstances, Altman dispatched a runner to Smoak, informing him of the situation. By this time the company was sustaining a number of casualties from mortar fire as well as rifles and machine-gun.112

When he received Altman's message (at 1200), Smoak was leading his battalion about 1200 yards south of the trail junction. His departure had been delayed by the late arrival of the forward observer team and difficulty in supplying his troops in their swampy assembly area. Acting on the meager information contained in Altman's message, Smoak immediately reduced his flank security, and proceeded down the trail as rapidly as possible in order to bring prompt support to Altman. One platoon of Company F was left behind to furnish security for the forward observer's wire team.

By 1245 the battalion was about 200 yards in rear of Company E. Here Smoak learned that Company E was pinned down by heavy fire and was slowly being cut to pieces; that reinforcement was needed immediately; and that the enemy opposition was located south of the trail junction. Smoak promptly ordered forward Company G (Captain William H. McDonough), to give needed assistance to Company E, while Company H (Major Edward A. Clark) was ordered to set up 81mm mortars to support the attack. Company F, less the platoon protecting the wire team, was ordered to a reserve position to await orders. Major Glenn E. Fissel, Smoak's executive officer, was ordered up with the artillery forward observer's party, to make an estimate of the situation and call in artillery concentrations to prevent the Japanese from maneuvering.113

Upon arrival in Company E's lines, Fissel realized that the reports which had reached the battalion commander were substantially correct. He observed that the greatest volume of fire was coming from the east side of the trail, in the direction of Piva River. Therefore, he promptly called for an artillery concentration in that area.

In the meantime, however, Smoak continued to receive conflicting reports. In order to obtain more accurate information he displaced his command post forward into the edge of the coconut grove through which the Numa Numa Trail ran. At this juncture, Fissel phoned Smoak and told him that Company E needed help immediately. Smoak, after a quick reconnaissance, ordered Company F (Captain Robert P. Rapp) to pass through Company E, resume the attack, and allow Company E to withdraw, reorganize, and take up a protective position on the battalion right flank. Company G, which had reached a position to the left of Company E, was ordered to hold. Company F began its movement forward. Company E, finding an opportunity to disengage itself began a withdrawal, redeploying on the right of the battalion position. Unfortunately, however, Company F made contact neither with Company E nor with Company G, and in the meantime, Fissel was wounded.114 Smoak therefore sent several staff officers to determine the exact positions of his companies. Company F could not be found, and a large gap existed between the right flank of Company G and the left flank of Company E. This left the battalion in a precarious position.115

As a result of the reports of his staff officers, Smoak ordered Company E to move forward, contact Company G, and establish a line to protect the battalion front and right flank. Company G, in the meantime, was to extend its line to the right in order to tie in with Company E. By 1630 Smoak decided to dig in for the night. His companies had suffered fairly heavy casualties; Company F was completely missing; and communication with regimental headquarters and the artillery had been broken. Further attempts to press an attack at this time would have been unsound.116

Map 11

Battle of Coconut Grove

First Phase, 13 Nov 1943

(Attack by 2d Bn, 21st Marines)At 1700 the gunnery sergeant of Company F reported in person to the battalion command post. The story he had to tell Colonel Smoak was discouraging. It appeared that Company F had moved out as ordered from its reserve position to the lines held by Company E. In the approach, however, Company F veered too far to the right and had missed Company E entirely. Company F proceeded onward, however, and went completely around the left, east flank of the enemy, ending in a position behind the Japanese lines. Captain Rapp found it increasingly difficult to control his Company. There were some casualties. Platoons intermingled and became disorganized. On hearing this story, Colonel Smoak ordered the gunnery sergeant to go back to Company F and guide it back to the battalion position. By 1745 Company F was back in the battalion lines and had taken a position on the perimeter which was set up for the night.117

At 1830 communications were reestablished and the 12th Marines were ordered to register on the north, east, and west sides of Smoak's perimeter. The 2d Raider Battalion, then attached to the 21st Marines, was directed to protect the supply line from the main line of resistance to the 2d Battalion, 21st Marines. Colonel Ames ordered Smoak to send out patrols and prepare to attack the Japanese in the morning, with tank, artillery, and aircraft support. No action other than sporadic enemy rifle fire occurred throughout the night.118

On the morning of 14 November all companies established outposts about 75 yards in front of the perimeter, and sent out patrols. At 0810 friendly aircraft from VMTB-143 appeared overhead, and Ames informed Smoak that these planes were ready to bomb and strafe the objective. Since patrols were out, and since the water supply was exhausted, Smoak had to wait until 0905 before he felt ready to call in the air strike.119 At this time, artillery marked the target with smoke, and 18 Marine TBF's120 effectively bombed the area. Immediately after this attack, Company E moved back into its

original position in the line. Smoak then ordered an attack, the time of which was based on arrival of water for the troops. Company E on the left and Company G on the right were to be in assault. Companies F and H would constitute the reserve. As designed, the attack was to be a simple frontal assault (supported by the 2d Platoon, Company B, 3d Tank Battalion), with each assault company attacking on a frontage of 100 yards on its particular side of the trail, the guide being toward the center. The tank platoon (five medium tanks) which had arrived a short time earlier, was to attack in line, equally spaced across the front.121

At 1015 water arrived and H-hour was set for 1100. At 1045, however, communications were again broken, so the attack was ordered delayed. At 1115, communications were reestablished, and H-hour was set at 1155. The 2d Battalion, 12th Marines, in direct support, arranged to provide a 20-minute preparation followed by a rolling barrage.122