Chapter 7

SEVENTH PERIOD

SCHNORCHEL U-BOATS OPERATE IN BRITISH HOME WATERS

JUNE 1944 - END OF WAR

In many respects this last period of the U-boat war resembled the first period. The U-boat war was again subsidiary to, and largely influenced by,

military operations in Europe. The U-boats were driven from their bases on the Bay of Biscay, which they had used for four years, and were forced to

return to bases in Norway and the Baltic. The waters around the British Isles again became the main area of U-boat activity, as Schnorchel-equipped U-boats

were able to operate in inshore waters with relative safety from aircraft detection. The U-boats were operating mostly submerged, not from choice as in the

first period, but because they had been forced under by Allied aircraft. Surface craft again became the main destroyers of U-boats.

The U-boats found that operations in inshore waters were just as hazardous during this period as they had been at the beginning of the war. The chief

difference was that during this period the average U-boat was able to sink only one-twentieth the amount of shipping that it sank in the first period.

Allied escorts were more numerous, more experienced, and better equipped, while the U-boats' offensive power was greatly reduced by their loss of mobility.

U-boat morale was also much lower during this period than it had been early in the war.

The lull in U-boat activity ended with the Allied landings in Normandy on Tune 6, 1944. The Allies had appreciated that the U-boats were a very serious

potential threat to the success of the invasion. The size of the U-boat fleet at that time was still such that a mass attack in the Channel on D-day, from

both flanks, might have saturated the defenses and inflicted grave losses on Allied convoys during the critical early days of the operation.

The Allied countermeasures involved blocking off the cross-Channel Area and guarding the convoy routes leading to it, with the object of making the

approaches to both a difficult and exhausting operation for the U-boats. By June 6, ten escort groups, consisting of 54 ships, were ready to block the

western approaches to the Channel. They were supported by three escort carriers, which were there chiefly to provide fighter support to escorts operating

close to the enemy shores. The enemy air threat proved, however, to be so slight that these carriers were withdrawn by June 11. Coastal Command aircraft

put on an intensive flying effort in the Channel and its western approaches and also in the Bay of Biscay Area. These dispositions of anti-U-boat forces

were independent of, and in addition to, the escorts and aircraft provided for close escort duties with the convoys running to and from France.

The first reaction of the U-boats to the invasion was a considerable exodus of U-boats from the French ports on 1-day, as soon as the enemy woke up to

the fact that the operation had really started. The number of U-boats in the Biscay-Channel Area increased from one on June 5 to about 20 on June 8. The

majority of these U-boats made no attempt to enter the Channel but, instead, set up defensive patrols off the Biscay ports to counter possible invasion

attempts in that area.

A curious feature of these operations was that they began with a large number of sightings and attacks on U-boats by aircraft and then, after a period

of several days, the number of contacts was sharply reduced. This reduction was due to the extensive use of Schnorchel by the U-boats, which had begun at

that time. It seems that the U-boat captains had not taken very kindly to the Schnorchel with all the discomforts that it was capable of causing in

inexperienced hands, and intended to use it only as a last resort, if the weight of air power against them became intolerable. After six U-boats were

sunk by aircraft attacks in the Biscay Area between June 7 and 10, the Uboats began to appreciate the value of Schnorchel and quickly learned how to use

it efficiently.

It is also possible that the enemy intended to operate his U-boats in the Channel, accepting all risks and proceeding on the surface in order to reach

the vital invasion area and disrupt the Allied landing

--64--

operations. It was the initial blows dealt him by Coastal Command in the early days of the operation that forced him to adopt the more cautious, and

less effective, tactics of remaining continuously submerged, which the advent of Schnorchel gave him the means of doing. The Schnorchel was a very poor

radar target, even at short range, and was difficult to sight, even in daylight. To attack it at night required exceptionally good radar tracking and

Leigh-light or flare technique.

In addition to their successes in the Bay of Biscay, Coastal Command aircraft contributed an outstanding performance in June against U-boats in

Norwegian waters. Most of these U-boats were probably en route for the English Channel to join in operations there. These U-boats continued to operate

mainly on the surface, and Coastal Command aircraft sank seven in Norwegian waters during June.

The first surface craft kill in the Biscay-Channel Area did not come until June 18. This was followed by four other surface craft kills, two with

the help of aircraft, before the end of the month. There was only one aircraft kill in the Biscay-Channel Area between June 11 and the end of the month.

The U-boats obtained their first successes against merchant shipping in the invasion area more than three weeks after D-day, and sank five ships

in the last few days of June. Two escort vessels were torpedoed by U-boats in the middle of June. When these results are measured against the 12

U-boats sunk in the same area in June by Allied forces, it is clear that the U-boats failed completely in their attempt to disrupt the Allied invasion.

The other enemy weapons (aircraft, surface craft, and mines) were equally ineffective against the thousands of Allied ships that moved across the

Channel to Normandy. Only 18 ships of 75,000 gross tons were sunk in the Biscay-Channel Area in June 1944, as a result of all forms of enemy action.

The Allies scuttled over 50 merchant vessels of about 300,000 gross tons in constructing the artificial ports that were used so successfully during

the invasion.

The enemy turned to other offensive weapons in July, such as the human torpedo, explosive motor boats, and the V-1 bomb, but they did very little

damage to Allied shipping. The experience in the Biscay-Channel Area during July and August was similar to that in June. The Allies continued to keep

up their pressure on the U-boats, while the U-boats found the approaches to the shipping lanes so difficult that those who reached them fumbled the

opportunities they found. U-boats operating in this area sank only two merchant vessels in July and six in August, while the Allies sank nine U-boats

in July and 12 in August.

Surface craft played the predominant role in sinking U-boats in this area during these two months, killing 13 of them alone and destroying three

others with the assistance of aircraft, out of the total of 21 sunk. An outstanding feature of the surface craft attacks in the invasion area was the

difficulty experienced in the initial detection of U-boats which adopted anti-Asdic tactics of resting on the bottom when escort vessels were heard

approaching. Numerous wrecks, together with the difficult water conditions and the high reverberation background in shallow waters, gave the U-boat

almost complete immunity from Asdic detection. However, once the Asdic picked up the U-boat contact and identified it as such, the chance of

obtaining a kill rose to a peak of about 50 per cent in the invasion operation.

The Second Escort Group continued its brilliant career during a ten-day patrol in the Biscay-Channel Area early in August. It achieved the

first destruction of a U-boat by Squid and also took part in the sinking of two other U-boats. The Squid kill was remarkably quick. One pattern

of six Squid charges was sufficient to bring the U-boat to the surface, and the crew rapidly abandoned the sinking U-boat.

The breakthrough of Allied land forces across the Cherbourg peninsula in the first week of August threatened the enemy's Biscay ports and

forced their evacuation. The U-boats abandoned their efforts on the Biscay-Channel Area toward the end of August and headed for Norwegian ports.

This marked the end of the first phase of the U-boat campaign against cross-Channel Allied shipping.

The enemy concentrated his main effort against the Allied invasion during the first three months of this period, and U-boat activity in other

areas was slight. The average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic during June 1944 was about 48, and over half of these were concentrated in

the Biscay-Channel Area and the Northern Transit Area-East.

World-wide shipping losses to U-boats continued to be low as only 11 ships of 58,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats in June. Besides the five

ships sunk in the Biscay-Channel Area, there were three ships sunk in the rest of the Atlantic and three ships sunk in the Indian Ocean.

--65--

|

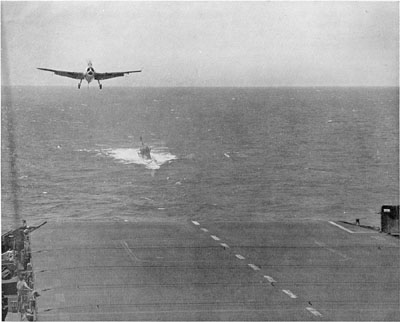

FIGURE 1. Boarding party from USS Guadalcanal labors to keep the captured U-505 afloat after its crew had

abandoned it to sink. |

The total number of U-boats sunk during June was 28, about the same as the high level reached in May. Besides the 21 U-boats sunk in the waters

around the British Isles, four others were disposed of in widely distant parts of the Atlantic by U. S. escort carrier groups. One of these four was

U-505, which was captured by USS Guadalcanal [CVE] and her escorts on June 4, 1944.

This task group sailed from Norfolk in May 1944 with the avowed intention of capturing an enemy submarine. It was felt that there was a good

opportunity to capture a U-boat that surfaced, by concentrating anti-personnel weapons on it, holding back on weapons that would sink it, and making

an attempt to board it as soon as possible. After an unproductive hunt around the Cape Verde Islands, a well-conducted search plan was put in operation

on May 31 for an estimated homebound U-boat. The USS Chatelain [DE], one of the escorts, made sonar contact at about 1000 on June 4. A Hedgehog attack,

followed by a shallow depth-charge attack, brought the U-boat to the surface at 1023 and fire was opened. The U-boat crew scrambled on deck and dived

overboard. At 1027, "Cease firing" was ordered.

The U-boat was then running in a tight circle at about seven knots, fully surfaced, and it was known that most of her crew had abandoned her.

USS Pillsbury [DE], another escort, lowered a whaleboat with a boarding party and then attempted to rope the U-boat. Meanwhile, the boarding party

got alongside and leaped from the whaleboat to the deck of the circling U-boat. There was only one dead man on deck and no one below, and the boarding

parties immediately set to work closing valves and disconnecting demolition charges. The Guadalcanal took the U-boat in tow, but many difficulties were

encountered as the towlines broke and the U-boat showed signs of settling. It was not until June 8 that the U-boat was at fully surfaced trim. This was

the first time that a U-boat had been captured by the U. S. forces.

U-505 was finally brought to Bermuda and the

--66--

|

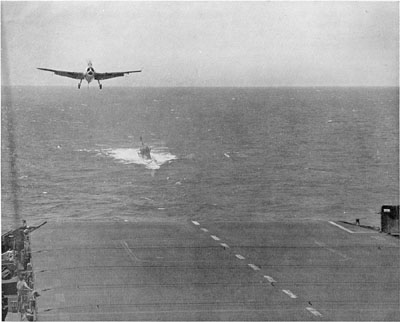

FIGURE 2. A torpedo plane approaches for a landing while USS Guadalcanal tows U-505 astern. |

Allies were able to extract a great deal of extremely valuable technical information from the manuals and equipment aboard the U-boat. In addition

to more reliable data on the acoustic torpedo, German search receivers, and other standard U-boat equipment, the Allies obtained important information

about German war orders, communications, and codes. Much of this information proved to be of value in conducting later operations against the U-boats,

as the Germans did not know that we had captured a U-boat and obtained this information.

World-wide shipping losses stayed low in July 1944 as only 12 ships of 63,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats. In addition to the two ships sunk in

the Biscay-Channel Area, five ships were sunk in the rest of the Atlantic and five in the Indian Ocean. The number of U-boats sunk throughout the world

in July was 22, slightly less than in June. Escorts of USS Card [CVE] eliminated a potential threat to Allied shipping by sinking a 1600-ton minelaying

U-boat early in July. This U-boat carried 66 mines, the moored acoustic type, which were intended to be laid in the approaches to Halifax.

August 1944 was the best month of this last period for the U-boats, as they sank 18 ships of 99,000 gross tons throughout the world. This peak score,

however, is only about the same as the average monthly sinkage achieved by U-boats during the previous period, which was a rather low average, at that.

Besides the six ships sunk in the Biscay-Channel Area, there were only two ships sunk in the remainder of the Atlantic. U-boats sank one ship in the Black

Sea and nine ships in the Indian Ocean, mostly off East Africa in the Mozambique Channel. The landings in Southern France took place during August without

the loss of any ships in the entire invasion area.

--67--

The downward trend in the number of U-boats sunk monthly continued during August as only 17 were sunk. Aircraft found it more difficult to detect

and attack the Schnorchel U-boat. Apart from the 12 U-boats sunk in the Biscay-Channel Area, there were only three U-boats sunk in the Atlantic, all by

escort carrier task groups. Aircraft from HMS Vindex, which was escorting the North Russian convoys, sank two U-boats, while aircraft from the USS Bogue

sank U-1229 south of Newfoundland, after a 20-day search. This U-boat, traveling on Schnorchel, had remained submerged for about 14 days, surfacing only

for a short daily interval of 10 to 15 minutes to determine her position.

The most significant development in August, with regard to future U-boat operations, was the advance of Allied armies in Western France which forced

the U-boats to abandon their bases on the Bay of Biscay. These bases contained the redoubtable Todt concrete shelters which had withstood heavy Allied

attacks for years. The basic strategy of German naval warfare in the Atlantic had depended upon the successful use and maintenance of the Biscay bases,

from which U-boats could proceed directly to their operational areas with minimum fuel consumption and less throttling opposition from Allied air and

surface patrols.

By the end of August it was evident that the U-boats had begun their final exodus from the Biscay ports and were heading for Norway, where they would

be much more vulnerable to Allied air attack. The problems of repair and maintenance of a large U-boat fleet at the small and inadequately equipped

Norwegian bases would also be much more difficult. The main effect, however, of the loss of the Biscay bases was the considerable increase in the length

of voyages to operating areas. The 500-ton U-boats, which comprised the majority of the U-boat fleet, were thereafter restricted to operations around the

British Isles, as it was extremely difficult to refuel at sea. Even the 740-ton U-boats confined most of their later operations to the nearby Atlantic,

operating near Canada and Gibraltar.

During September 1944 the enemy seemed to be concerned primarily with shifting his U-boats from the Bay of Biscay to Norwegian bases. About 25 U-boats

were engaged solely in running the gauntlet of Allied air and surface patrols between France and Norway. These U-boats traveled submerged for almost the

entire trip, using Schnorchel, and most of them completed the journey safely. As a result of this mass transit of U-boats, the average number at sea in

the Atlantic reached a peak for this last period during September when there were 57 U-boats at sea.

World-wide shipping losses were considerably reduced in September as only seven ships of 43,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats. A noteworthy feature

was the almost complete absence of U-boat activity in the Indian Ocean. One ship was sunk there early in the month, but the U-boat responsible for this

sinking withdrew towards Penang where it was torpedoed by a British submarine. Although the other six ships sunk by U-boats during the month were all lost

in the Atlantic, not a single ship was stink in the formerly active Biscay-Channel Area. Two ships were sunk in the Barents Sea Area and one in the

Canadian Coastal Zone. The other three ships were sunk early in September, from North Atlantic convoys, by U-boats operating on Schnorchel in inshore

waters. These U-boats operated in the Northwestern Approaches to England, in an area of high shipping density through which the North Atlantic convoys

passed on their way in and out of the North Channel. Fortunately, no further losses occurred in this area, as the Allies started routing the North

Atlantic convoys around the south of Ireland at about this time.

The total number of U-boats sunk in September was 21. This included, however, six 300-ton U-boats that were scuttled in the Black Sea as a result

of Russian advances in eastern Europe. In the Mediterranean, two of the three U-boats based at Salamis were destroyed. The general clearance of U-boats

and enemy aircraft from the Mediterranean enabled the number of ships employed in convoy escort to be reduced and a large number of independent sailings

was permitted. Only ten U-boats were stink in the Atlantic. This steady decrease reflected the inactivity of the U-boats and the increased effectiveness

of Schnorchel. Two of these U-boats were sunk as a result of the inshore activity in the Northwestern Approaches to England, five were sunk in the

Northern Transit Area-East, and three in the remainder of the Atlantic.

By the end of September the last of the U-boats appeared to have departed from the Biscay-Channel Area. The average number of U-boats out at sea

in the Atlantic declined to about 30 in October, with most of them still in transit. The results achieved by German U-boats reflect this situation,

as October

--68--

1944 was the first month of the war during which they were not able to sink even a single ship in the Atlantic. As a matter of fact, the U-boats

sank only one ship of 7000 gross tons during October. A perfect record for the month was spoiled on October 30, when a Japanese U-boat sank a U. S.

cargo ship, traveling independently in the Pacific, midway between San Francisco and Pearl Harbor. Ironically, this was the first ship sunk in the

Pacific by a U-boat since November 1943. The lull in U-boat activity was reflected on the east coast of the United States, as October was the first

complete month of independent sailings for all ships engaged in coastal trade (except for dry cargo vessels of 8 to 10 knots).

Only nine U-boats were sunk during October, five of them in the Pacific and only four in the Atlantic. All four of the latter were stink in the

Northern Transit Area-East, the area through which the U-boats traveled to and from their Norwegian bases. One of these four U-boats was sunk as the

result of a bombing raid on Bergen. One of the five U-boats sunk in the Pacific was a German U-boat, sunk by the Dutch submarine HNMS Zwaardvisch in

the Java Sea. This was by far the most easterly position in which a German U-boat had ever been destroyed.

Although the average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic during November was only 24, the lowest monthly average of this period, the enemy

had completed his transfer of U-boats from the Biscay bases, and the U-boats at sea were more active. Seven ships of 30,000 gross tons were sunk by

U-boats in November 1944; two ships in the Indian Ocean, a Swedish ship in the Baltic, and four ships in inshore waters in the Atlantic. Three of

these ships were sunk on November 10 in the approaches to Reykjavik, Iceland. The other ship was stink in the English Channel toward the end of the

month after several months without any U-boat activity in this area.

The number of U-boats stink during November was 10, but seven of these U-boat kills took place in the Pacific and only three in the Atlantic. This

was the smallest monthly number of U-boats stink in the Atlantic since January 1942. Two of these U-boats were sunk in the Northern Transit Area-East

and one in the Biscay-Channel Area.

The main reasons for the meager results achieved by the Allies in sinking U-boats during these three months, September through November, was the

extreme caution displayed by the U-boats as the average U-boat sank less than 1/10 of a ship per month at sea. Increased experience in the use of

Schnorchel enabled the U-boats to avoid Allied air patrols by remaining submerged for prolonged periods and lying in wait for Allied convoys in focal

areas inshore. Then, the U-boats developed their bottoming tactics in inshore waters, where wrecks and non-sub contacts were abundant and where the

high reverberation background tended to drown out weak Asdic echoes. In addition, the necessity for the use of anti-Gnat noisemakers by Allied ships

made Asdic detection more difficult.

The experience during these three months indicated to the enemy that U-boats could again operate in inshore waters, with Schnorchel, without

suffering undue losses. This, in effect, made unnecessary the previous long voyages to distant areas which had been made in order to avoid the heavy

Allied air coverage in the North Atlantic. The enemy, there-fore, had by the use of Schnorchel overcome to some extent the great strategic disadvantage

resulting from the loss of his Biscay bases. The use of Schnorchel enabled U-boats to proceed to and from their bases in Norway and the Baltic via the

Faeroes-Shetland passage instead of the more circuitous passage south of Iceland. The U-boats could operate effectively in all areas of the North

Atlantic, particularly in the waters around England, where the high density of important shipping provided an attractive target near the U-boat bases.

December 1944 witnessed the beginning of a steady increase in the number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic. Coincident with the German land

offensive on the Western Front (Battle of the Bulge), about five U-boats commenced operations in the central English Channel in an attempt to

impede the flow of troops and supplies to the Allied armies in Europe. Seven ships and one escort were sunk by U-boats in the Biscay-Channel Area

during December, with most of the damage being done toward the end of the month by two U-boats, both of whom escaped to tell of their success.

During the same period an abortive offensive was launched by a flotilla of midget U-boats (Biber) against convoys in the Scheldt Approaches, off

the Dutch coast. Only one ship was sunk while 15 midget U-boats were sunk or captured.

U-boat activity in other areas was slight during December as the world-wide shipping losses to U-boats totaled only nine ships of 59,000 gross

tons. An independent ship was sunk in the Gulf of Maine on December 3 by the same U-boat that landed two

--69--

enemy agents on the coast of Maine on November 29. The other ship was sunk in the Pacific off the southeast coast of Australia by a German U-boat,

the first sinking in these waters since May 1943.

Nine U-boats were sunk during December, one in the Indian Ocean and eight in the Atlantic. Six of the eight U-boats sunk in the Atlantic were lost

in the waters around England, particularly in the Biscay-Channel Area and the Northern Transit Area East. One of the three U-boats in the Biscay-Channel

Area ran aground on Wolf Rock due to navigational difficulties.

U-boat activity continued to increase (luring January 1945 as 11 ships of 57,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats. All 11 of these ships were stink in

the Atlantic by U-boats operating in inshore waters. In United Kingdom waters, there were no sinkings in the English Channel, although U-boats were still

patrolling there, and the center of activity shifted to the Irish Sea, where six ships were sunk during the month by U-boats which had penetrated into the

region, although it had long been considered safe from enemy attacks and had been used for training.

The other inshore areas of U-boat activity in January were off Halifax, where four ships were sunk and another damaged, and the western approaches to

Gibraltar, where one ship and an escort vessel were sunk and another ship damaged. Three of the four ships sunk off Halifax were torpedoed on January 14,

(luring daylight, out of a convoy nearing port. The escorts were not successful in locating the U-boat.

The number of U-boats sunk monthly reached a low for this period as only six U-boats were sunk during January, one in the Pacific and five in the

Atlantic. All of these kills were made by surface craft during the latter half of the month. Not a single U-boat was sunk by aircraft during January

1945. The first of these sinkings occurred on January 16, when a U. S. destroyer escort task group sank a weather-reporting U-boat in the Northwest

Atlantic Area. Using information based on the U-boat plot, the group departed from the Azores for the general area of the last fix. An HF/DF fix, at

a range of 10 miles, further localized the probable area of the U-boat and the hunt got underway. Some 2i/2 hours later, sonar contact was gained,

and one Hedgehog attack and five Mk 8 depth-charge attacks resulted in the sinking of the U-boat.

The other four U-boats sunk in the Atlantic during January were all stink in United Kingdom coastal waters by British surface craft. Three of these

kills resulted from Asdic contacts made shortly after ships were torpedoed. The)' were particularly encouraging in that they represented some evidence

that ships were finally learning how to attack U-boats operating in inshore waters, after months of disappointing patrols in generally difficult conditions.

In addition to these successes, indirect but effective anti-U-boat operations were carried out by the Russian armies during January. By overrunning

East Prussia, they threatened the important working-up bases in the eastern Baltic, and by entering Silesia they paralyzed part of the elaborate organization

for the construction of the new type U-boats. It is estimated that the yards at Danzig alone produced almost a third of the new Type XXI prefabricated

U-boats. Not only were the Norwegian and western Baltic ports severely taxed by assuming the additional burden of handling surface vessels and U-boats

previously based in the eastern ports, but the concentration of all U-boat facilities in the western Baltic made them much more vulnerable to Allied

air attacks.

The U-boats were more aggressive in February 1945 and sank 15 ships of 65,000 gross tons. One ship was sunk in the Indian Ocean, off the west coast

of Australia, and the other 14 ships were sunk in the Atlantic, the peak monthly score for this period. With the land warfare in Europe approaching

Germany, the enemy's objective seemed to be to sink the maximum shipping in the short time remaining. Consequently, the major U-boat effort was

concentrated in British coastal waters, where nine ships were stink during the month, mainly in the southwest approaches to the English Channel and

in the North Sea off the east coast of England. The five ships sunk in the remainder of the Atlantic included two in the Barents Sea Area, one near

Iceland, one near Gibraltar, and one in the Southeast Atlantic by a U-boat homeward bound from the Indian Ocean.

The number of U-boats sunk monthly increased sharply as 19 U-boats were sunk in February, indicating that the kills near the end of January

initiated a new period of good hunting. Twelve of the 14 U-boat kills in the Atlantic took place in the waters around England, but there was a

shift of activity to the northward. The Tenth Escort Group carried out a particularly successful patrol in the area between the Shetlands and the

Faeroes against U-boats on

--70--

passage to their operational areas, sinking three of them. These three attacks all resulted from initial Asdic contacts on submerged U-boats.

Ten of the 14 kills in the Atlantic were made by surface craft as Asdic was becoming much more effective against U-boats in shallow inshore waters

due to the increased experience of Allied ships under these conditions. The other two U-boat kills in the Atlantic occurred in the Barents Sea Area

and off Gibraltar.

Five Japanese U-boats were sunk during February in the Pacific, where the U. S. submarine USS Batfish turned in a record performance by sinking

three U-boats in four days. These were torpedoed north of Luzon between February 9 and 12. In each case, the Batfish detected Japanese radar signals

on her search receiver [APR] and then homed on the U-boat.

The number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic increased sharply in March 1945, averaging over 50 for the month. Most of these were concentrated in

the waters around England, but there were some signs of a shift of U-boat activity to deeper waters in the Atlantic, possibly indicating that the enemy

had appreciated that some escorts had been removed from ocean convoys to operate in inshore waters. There was also some evidence that Type XXIII U-boats

operated in the North Sea, off the east coast of England.

Despite the increase in the number of U-boats at sea, the world-wide shipping losses to U-boats stayed at the same level in March 1945 as only 13

ships of 65,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats, all in the Atlantic. Nine of these ships were sunk in the waters around England, seven of them in the

Biscay-Channel Area. Two ships were sunk in the Barents Sea Area and another two were sunk in the Brazilian and Caribbean Areas by a U-boat homeward

bound from the Indian Ocean. Midgets probably sank another three ships in the North Sea Area.

The number of U-boats sunk during March continued high as 19 were destroyed, 2 in the Pacific and 17 in the Atlantic. Four U-boats were destroyed by

our raids in German ports and one was sunk in the Canadian Coastal Zone by a U. S. destroyer escort killer group. The other 12 U-boats were sunk in the

waters around Great Britain; one by aircraft, two by mines, and nine by surface craft. The Twenty-First Escort Group turned in a notable performance by

sinking three U-boats in four days, north of Scotland.

In April 1915, shipping casualties were of the same order of magnitude as in March, as 13 ships of 73,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats. All of these

ships were sunk in the Atlantic: two off Cape Hatteras in Eastern Sea Frontier, one in Kola Inlet in the Barents Sea Area, and the other ten in coastal

waters around England, mainly in the Channel Area.

The tempo of U-boat operations in April gave no indication that the end of the war was at hand. With remarkable determination the enemy maintained his

U-boat offensive in inshore waters to the very end of the war. No relaxation of effort or hesitation to incur risk was apparent until the German surrender

on May 8, 1945. A U. S. cargo vessel was sunk off Rhode Island on May 5, but a U. S. destroyer escort task group gained sonar contact later that night and

destroyed the U-boat. On May 7, a U-boat sank two merchant ships from a coastal convoy near the Firth of Forth. These were the last merchant ships sunk by

U-boats in World War II, as Japanese U-boats did not sink a single merchant ship between V-E Day, May 8 and V-J Day, August 14, 1945, while six Japanese

U-boats were sunk in that interval.

The 36 U-boats stink during April 1945 made the highest monthly score of the last period. Five of these U-boats were sunk in the Pacific and the

other 31 were sunk in the Atlantic, with surface craft accounting for 19 kills, the highest monthly score of the war for them. Twenty-two of these

U-boats were sunk in the waters around England, three in the Barents Sea Area, two along the east coast of the United States, and four in Northwest

Atlantic Area. These four U-boats were part of a group of six (Group Seawolf) engaged in a joint westward sweep of North Atlantic convoy lanes while

en route to operations off the U. S. coast. Escorts of U. S. escort carrier task groups that conducted a barrier patrol which intercepted this group

of U-boats were responsible for these four kills. On the last day of April, a U. S. Navy MAD-equipped plane sank a U-boat in the Biscay-Channel Area

with retro-bombs.

During the first week of May, aircraft operated with great effectiveness in Danish waters against U-boats attempting to escape to Norway, sinking

about ten of them with rockets and gunfire. In addition to the kills enumerated above, it is estimated that the heavy bombing raids on German ports

in the Baltic probably accounted for the destruction of over 25 U-boats in port during the last month of the war.

On May 4 a short signal was transmitted on all U-boat frequencies. By this signal, Doenitz had

--71--

ordered his U-boats to cease hostilities. In an Order of the Day issued at the same time, he explained that a crushing superiority had compressed

the U-boats into a very narrow area and that the continuation of the struggle was impossible from the bases which remained. By May 31, 49 U-boats had

surrendered at sea leaving a small number unaccounted for. The last of these to turn up was U-977 which surrendered at Buenos Aires on August 17, 1945,

after the surrender of Japan. In addition to the U-boats which surrendered at sea, huge numbers were captured in ports or scuttled.

The end of the war thus saw the U-boat fleet held in check but still carrying out operations on a major scale. It had never been driven off the seas

and might well have increased substantially in numbers and power, had the war been extended for any appreciable period. New-type U-boats were just coming

into service at the end of the war. About six Type XXIII U-boats had operated with fair success off the east coast of the United Kingdom and at least that

number of Type XXI U-boats had reached ports in Norway with the intention of sailing in the immediate future for offensive operations. One is believed to

have actually started on patrol, but it was forced to turn back due to some failure in equipment. The U-boat was by no means eliminated as a weapon of war

when Germany surrendered, and the new types which Germany was introducing would have raised serious problems for the Allies had they ever reached

large-scale use.

| 7.2 |

COUNTERMEASURES TO THE U-BOAT |

Shipping in convoy during this last period was safer than in any previous one. Although the number of convoyed ships at sea was at its peak, only

six ships were sunk monthly by U-boats. Of the 1100 ships that sailed monthly in the North Atlantic convoys, only about one was sunk monthly by U-boats,

usually in the vicinity of England. The loss rate was therefore less than 1/10 of 1 per cent.

The proportion of shipping sunk by U-boats, which was in convoy when sunk in contrast to independent sailings, increased to about 55 per cent during

this period. This increase was due to the fact that U-boats, operating on Schnorchel in inshore waters, found it desirable to operate in areas of high

shipping density, that is, along the convoy lanes. The experience during this period differed from the past in that most of the shipping losses occurred

at the terminals of the convoy routes, instead of in the middle. The principle of defense in depth contributed greatly to the safety of convoyed shipping,

particularly in the case of the North Russian convoys. During this last period, there were often sufficient ships available so that, in addition to the

close escort, pickets could be stationed in an outer screen. Pickets could intercept surfaced U-boats, investigate surface ships, divert neutral ships,

and give the Escort Commander timely warning of impending dangers. Air patrols operated in the zone beyond the pickets.

The largest convoy of the war, HXS-300, consisting of 167 ships and seven mid-ocean escorts, sailed in July 1944. With 19 columns, this convoy had a

front of some nine miles. The ships in the convoy carried over a million tons of cargo to England. The convoy arrived safely and the fact that it was not

attacked may well have been due to the vigorous search by aircraft of the two MAC ships for the only U-boat reported in the vicinity.

Early in September 1944, following the transfer of the U-boats from the Biscay base to Norwegian ports, the Allies rerouted the North Atlantic convoys

around the south of Ireland, through St. George's Channel. Although not shortening the voyage between New York and Liverpool to any appreciable extent, the

southerly route did facilitate the joining and splitting of sections from and to the south coast of England and the Continent. It also got further away

from both the U-boats based in Norwegian and German ports and the rough weather of the higher latitudes. Convoy CU-37 was the first to sail to an Atlantic

port on the Continent, as one section arrived in Cherbourg on September 7. Antwerp was opened to Allied convoys on November 28.

The increased safety of convoys in the Atlantic enabled the Allies to make another change that would quicken the flow of shipping. Towards the end

of September 1944 the sailing interval for the HX and ON convoys was reduced to 5 days and the slow SC and ONS convoys were started again. This meant

that the convoys would not be as large as they had been in the previous months, but there would be more of them. The time spent in port by ships waiting

for convoys was cut materially by this change.

--72--

Similar steps were taken in the East Atlantic in November 1944. A single escort sailed with convoys between Gibraltar and the United Kingdom, although

additional protection was given at both ends. This more or less restored the arrangement which had been in force from the outbreak of the war until the

middle of 1941. Shipping between Gibraltar and Freetown was permitted to sail independently if there were no U-boats along the route. In the Mediterranean

convoying was abandoned except for troopships and local convoys near Italy and Greece.

In the last month of the war, April 1945, the average number of ships at sea in the Atlantic reached a maximum of 1400, about double the number in

the early months of 1943. About two-thirds of these ships were in convoy. Shipping in the Pacific also reached a new high in April, as there were about

900 ships at sea, with about one-third of them in convoy.

Most of the U-boat activity during this period was concentrated in the waters around England and consequently aircraft under Coastal Command

operational control played the major part in the offensive against the U-boats. At the end of the war, Coastal Command had more than 1100 planes

under its control, more than six times the number available at the start of the war. The invasion battle started in May 1944, when U-boats left

from Norwegian ports to reinforce the Biscay ports for the attack on the huge amount of Allied shipping which would have to be used for the build-up

of the Allied beachhead. Very few U-boats got through, as aircraft sank 17 U-boats and damaged 11 others in Norwegian waters between mid-May and the

end of July. Thus a depleted U-boat fleet was left to execute the plan to attack the invasion traffic.

As soon as the invasion had started, the U-boats headed for sea, staying on the surface and fighting back against aircraft with their automatic

37-mm gun. Coastal Command was ready, and within five days the enemy lost six U-boats while five were seriously damaged. The hectic few days after

D-day produced one of the outstanding achievements of the war, when a Liberator sank two U-boats at night within half an hour. After the first week

of the invasion, the enemy abandoned his ideas of staying on the surface and the all-Schnorchel era had begun. But the beachhead was already secure

and the U-boat fleet badly mauled. Between mid-May and the end of July Coastal Command aircraft sank 23 U-boats, shared two kills with surface craft,

and damaged 25 U-boats. The price paid for the success was 31 aircraft lost as a result of enemy action and 17 lost as a result of operational hazards.

Once the invasion beaches were secure, it became Coastal's job to protect shipping until victory was finally won. It was difficult to detect

Schnorchel at all and even after it was detected, the probability of attacking it successfully was lower than that for an attack on a surfaced U-boat.

All available aircraft were employed to hunt the Schnorchel and, although the number of kills was somewhat disappointing, only a few ships were sunk

in inshore waters. Thus the many hours of flying often without the consolation of a sighting were not wasted.

With the reduced opportunities to kill U-boats, Coastal Command began to look further afield. During 1945, there were a number of anti-U-boat sorties

in the Skagerrak, Kattegat, and the western Baltic. Liberators at night and rocket-fitted Mosquitos and Beaufighters during the day carried the war right

into the U-boats' home waters. Numerous attacks were made, some of them on the new type U-boats which were proceeding to Norwegian ports prior to setting

out on operations. The outstanding effort was a strike in the Kattegat by Mosquitos, which resulted in the sinking of three U-boats. In the final days of

the war, the last real action was seen when U-boats began to evacuate north German ports and run for Norway. Many attacks were made and about ten U-boats

are believed to have been sunk by aircraft in the first week of May 1945.

During the entire period aircraft operating under Coastal Command made about 38 sightings and 24 attacks monthly, about the same as in the previous

period although the concentration of U-boats in British waters was much higher in the last period. The use of Schnorchel resulted in a reduction in the

lethality of aircraft attacks, as only 18 per cent of them resulted in the sinking of a U-boat (about 25 per cent in previous period) and about 35 per

cent of the attacks resulted in at least some damage to the U-boat. About half of the aircraft kills made during this 11-month period occurred in the

first and last months (June 1944 and April 1945), when a high proportion of the U-boats were found on the surface.

Operational results during the last period indicated that Schnorchel was a most effective counter-

--73--

measure to Allied air power. Most of the U-boats were equipped with Schnorchel, fitted with a drumshaped aerial (Runddipol) which was pressure-tight,

but gave warning only of meter radar. The primary effect of Schnorchel was to cut visual and radar ranges from Allied aircraft by a factor of about 2 or

3. Toward the end of this period the Germans developed an effective anti-radar rubber-like covering for the Schnorchel, which was supposed to cut Allied

microwave radar ranges on Schnorchel by another factor of 3. The ranges at which many radar contacts would first be made were such as to place them within

the sea-return zone of Allied radar sets, where they were missed entirely. It has been estimated that the number of potential Schnorchel contacts missed at

short ranges is larger than the total number of' Schnorchel contacts made at all ranges.

These advantages of Schnorchel enabled U-boats to operate over long periods of time in restricted waters, with reasonable safety from aircraft, by

remaining bottomed most of the time and coming to Schnorchel depth only to recharge batteries. The effectiveness of aircraft hunts was also reduced as

the Schnorchel increased the submerged speed of U-boats for prolonged periods from about 2 or 3 knots to about 6 knots.

Schnorchel, however, also had its disadvantages. The offensive power of U-boats was greatly reduced as they were forced to give up the great mobility

of surfaced operations for the relatively slow speeds of Schnorchel operation. The efficiency of the periscope watch was impaired when the U-boat was at

Schnorchel depth, and the noise of the engines rendered the hydrophones practically useless. In addition, prolonged use of Schnorchel undoubtedly increased

personnel fatigue, as a result of varying air pressure, occasional fumes, and the more careful attention required to maintain depth control.

Despite these disadvantages, the U-boats preferred the feeling of security which the Schnorchel gave them to the alternative of operating on the

surface, and depending on their new directional microwave search radars for warning of aircraft. With the increased use of Schnorchel, the number of

U-boat contacts per 1000 flying hours steadily decreased and the ratio of Schnorchel contacts to all contacts steadily increased, passing the 50 per

cent mark in December 1944. Visual search became relatively more productive than radar search as occasional sightings at relatively long ranges were

made on the exhaust smoke or wake that sometimes accompanied the Schnorchel.

The Allies were not able to produce any really effective countermeasures to the Schnorchel by the end of the war. Increased stress was placed on the

use of binoculars in visual search and the most favorable altitudes for the detection of Schnorchel were determined. Tactical doctrines were modified to

take account of the decreased sweep widths of both radar and visual search. Modifications, such as the fast time constant [FTC] circuit, were made to

Allied radar sets to improve the efficiency of contact. The FTC circuit acted as a discriminator against sea return, thereby making it easier to distinguish

the Schnorchel blip. New high-power narrow-beam short-pulse radar sets were designed to provide better resolution in search for small targets. Tests

indicated that the new radar sets (AN/APS-3 and AN/APS-15), which operated in the X-band (3-cm) and had sharp beams, were better at detecting Schnorchel

than the earlier longer-wave-band radar sets.

Aircraft used sono-buoys more frequently towards the end of the war in order to take advantage of the high noise output of Schnorchelling U-boats.

Sonobuoys had been used successfully in a number of attacks by aircraft and escorts of U. S. escort carrier task groups and analyses indicated that in

over 50 per cent of the cases in which sono-buoys were dropped following visual contacts on U-boats a sono-buoy contact was obtained.

| 7.2.3 |

Scientific and Technical |

The Allies continued to perfect their equipment and tactics during this last period. More useful and flexible retiring search plans were developed

for surface craft. Operation Observant and similar search plans, based on the most probable location of the U-boat, provided ships with the means of

regaining contact with a U-boat once the general location was known. An analysis of surface craft hunts indicated that when the correct plan was used,

contact was regained in 44 per cent of the cases, while the incorrect plan led to success in only 28 per cent of the cases.

The U. S. Navy continued to improve its sonar equipment as experimental work was done with maintenance of deep contact feature [MDC] and depth-determining

gear. By the end of the war a new fast sinking influence depth charge had been developed, the Mark 14, which was considered to have

--74--

higher probability of doing lethal damage to a submerged U-boat than other depth charges. This charge was designed to fire at the nearest point of

approach to a U-boat by the change of frequency between the reflected signal and the supersonic signal emitted by the depth charge.

An analysis was made of the operational results obtained during 1943 and 1944 by British ships using depth charges, Hedgehog, and Squid. It indicated

that a single depth-charge pattern had about a 5 per cent chance of sinking a U-boat and a Hedgehog pattern at least a 15 per cent chance, while the Squid

attacks averaged about a 20 per cent chance of success. The double Squid pattern showed promise of being the most lethal weapon against U-boats, but this

was based on a small number of attacks.

The greatest technical effort of the Allies, however, was spent on the effort to develop satisfactory means for the detection of Schnorchel. As previously

mentioned, two main lines were followed: (1) the improvement of radar performance by choosing a design effective against small targets, and (2) the

improvement of sonar detection, in particular sonobuoys for detection from aircraft. The chief modification involved was increase in the operating life

of the buoys to reduce the number that had to be employed. In addition, directional sonobuoys were developed, which gave a more accurate submarine

position, but these did not see operational use.

The U-boat command again was prolific in developing new technical equipment for the U-boats in an effort to stave off the impending defeat. During

1944 the Germans introduced a new type of gear [LUT] on their torpedoes which enabled the line of advance of the torpedo, when zigzagging, to be pre-set

at any angle from its straight run. This gear also enabled the mean speed of advance to be pre-set at will. At the end of the war the Germans were

developing a new type of homing torpedo (Geier) which omitted supersonic signals and homed on the reflected echoes from the target.

During this period, the Germans modified their 740- and 1200-ton U-boats to enable them to dive as quickly as the 500-ton U-boats. The most distinctive

feature of these modified U-boats was the narrow cut-away deck forward.

Toward the end of the war, there were some indications that the Germans had developed an ultrahigh-speed method of communication (Kurier) using an

attachment to the normal U-boat transmitter. It appears that the message was recorded on a magnetic tape which was then run through at high speed. This

method of communication would counter Allied use of HF/DF.

Early in 1944 the U-boat command had come to a clearer appreciation of the true situation with regard to the Allied use of radar. They realized that

they needed an improved search receiver against S-band (10-cm) radar which would not only give ample warning but would provide a margin of sensitivity

against inevitable losses of efficiency under operational conditions. The enemy had also learned of X-band (3-cm) radar from a crashed H2X blind bombing

plane at the beginning of 1944 and the development of X-band search receivers was started by the Germans before Allied use of X-band radar in U-boat

search had produced many results.

The German solution to these problems appeared in the late spring of 1944 in the form of the "Tunis" search receiver. Tunis consisted of two antennas,

the "Mucke" horn for X-band radar and the "Cuba la" (Fliege) dipole and parabolic reflector for S-band radar, fitted with an untuned crystal detector and

connected to a Naxos 2 amplifier. Bearings were taken by rotating the DF loop on which the antennas were mounted. The X-band Mucke horn had a beam width of

about 15° so that bearings on 3-cm radar were quite accurate. The S-band Fliege antenna detected l0-cm radar transmissions through a sector of about

90°.

The chief feature of this equipment was the directional antennas, which gave increased sensitivity and range. In order to obtain the necessary sensitivity

with these aerials, the Germans had to sacrifice the desirable property of all-around looking and the aerials had to be continuously rotated by the bridge

watch. The units still had to be dismounted and taken below on submergence, and so could not be used on Schnorchel.

Allied tests on captured equipment indicated that Tunis was simple to operate and dependable under normal operational conditions. These tests indicated

that expected operational ranges on Allied radar sets would vary from about 20 miles for planes at 500 feet altitude to about 40 miles for planes flying at

2000 feet. These expected operational ranges of Tunis were greater than the corresponding average radar ranges, both for S-band and X-band, on surfaced

U-boats. It was concluded that the Tunis search receiver was apparently a simple, efficient, and successful

--75--

countermeasure to both S-band and X-band radar.

The Tunis search receiver was used very infrequently by U-boats during this period and it is quite possible that the Germans were not aware of

how successful it could be against Allied radar. Tunis was developed shortly after Schnorchel had been fitted to the U-boats and never did receive

a fair trial in actual operations. The U-boats apparently did not have much faith in their technical experts, who had fumbled so badly in 1943, and

preferred the security offered by Schnorchel, despite its limitation for the offensive, to the risk of operating on the surface and depending on Tunis

for early warning of Allied aircraft. Then again Tunis offered no protection against possible new Allied radar sets on different frequencies or against

Allied aircraft not using radar at all, while Schnorchel did. It seems quite likely that the U-boats would have sunk considerably more shipping if they

had operated on the surface with Tunis, but the desire for safety was predominant and Schnorchel offered the better prospects for that.

All the centimeter aerials produced by the Germans had the disadvantage that they could not withstand submergence. The production of a suitable

pressure-tight aerial, urgently needed for use on Schnorchel, presented great technical difficulties which were not completely solved at the end of

the war. The only search receiver aerial that was fitted on Schnorchel was the old standard Runddipol type, which could detect only meter radar. There

were some signs that the Germans were developing a pressure-tight aerial at the end of the war, suitable for both S-band and X-band radar detection and

incorporating an infrared receiver as well.

During this period the Germans introduced a variety of midget U-boats (e.g.: Seehund, Molch, Biber, Hecht, and Marder), piloted by one or two men

from a pressure-tight control position and capable of complete submergence. The successful attack by British midget submarines on the Tirpitz on September

22, 1943, stimulated German interest in these craft. The flotillas operating these midget U-boats were not branches of the U-boat arm of the German Navy but

form part of an organization known as the Small Battle Units Command [KDK].

The Seehund (Type XXVII) was probably the most formidable of the midget U-boats. It was prefabricated, about 39 feet long, and displaced 16 tons. It

carried two torpedoes and a two-man crew. The surface speed was about 6 knots and submerged speed about 3 knots. The surface range was about 275 miles,

the endurance of the crew about three days, and the diving depth about 100 feet. It was fitted with a periscope.

Midget U-boats were used primarily in the invasion area and were generally ineffective, inflicting very little damage on Allied shipping while suffering

heavy losses. This may have been due partly to the fact that they were rushed into battle before they were perfected and before their crews were properly

trained. Their small size made it more difficult to detect them but they were extremely vulnerable to depth-charge attack. They were relatively slow and

unhandy, with a limited operational range, and only suitable for attacking merchant ships proceeding slowly in calm waters. It is estimated that about 80

midget U-boats were sunk or captured between December 23, 1944, when they started operations in the Channel Area, and the end of April 1945.

The heavy losses sustained by U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic forced the enemy to undertake the gigantic task of building a complete new frontline

U-boat fleet. Though faced with imminent invasion and with a great shortage of manpower, Germany employed a very large number of their skilled workmen in

the construction of prefabricated U-boats. This is a measure of the importance that the enemy attached to U-boat warfare and of the hopes which he

entertained for success in a new campaign.

The Type XXI U-boat was designed for high submerged speeds, primarily to get into a favorable attack position. Originally intended for turbine drive,

the high speed hull design for the Type XXI was completed before the Walter propulsion unit was ready and it was actually equipped with extra large

batteries to give the high maximum submerged speed of 15 to 18 knots. Its submerged endurance at a speed of 10 knots was about 11 hours. The type XXI

U-boat was about 250 feet long and its standard displacement about 1600 tons. The large torpedo room with 6 bow tubes was an answer to the demands for

increased armament. The U-boat carried a crew of 57 men and 20 torpedoes. Stern torpedo tubes were sacrificed to obtain greater speed. Silent-running

speeds of about 5 knots were obtained on electric motors when submerged. An improved extensible type of Schnorchel was fitted. The Type XXI U-boat used

diesel propulsion on the surface and had a maximum speed of 15 knots. It was a true ocean

--76--

going U-boat and its surface endurance was estimated to be greater than that of a%40-ton U-boat.

The Type XXIII U-boat was developed on requirements from the Mediterranean U-boat command for inshore waters and short cruises. These characteristics

were also useful for operations in the invasion area. The Type XXIII U-boat was about 114 feet long and its standard displacement was about 230 tons. It

had two bow tubes and carried only two torpedoes. The total crew consisted of only 14 men. Its maximum surface speed was 10 knots and its maximum submerged

speed 12 knots. The submerged endurance at 10 knots was about 4i2 hours.

Both Type XXI and Type XXIII U-boats were built by a system of prefabrication which fell into four stages. Basic parts were manufactured at a number of

widely dispersed factories situated along Germany's inland waterways. Sections of the hull were assembled at a number of shipyards and sent from them to

certain key yards for welding into complete U-boats, which were then fitted out under covered shelters. The final assembly yards for the Type XXI U-boats

were Hamburg, Bremen, and Danzig.

Speer's dispersal of his organization did much to defeat Allied bombing, but the indirect results of Allied raids were serious. The German transport

system was disrupted by Allied bombing of communications and this did much to set back the time schedule for the construction of these new U-boats. The

first prefabricated U-boat was completed in June 1944 and by the time the war ended, the enemy had completed about 120 Type XXI U-boats and about 60 Type

XXIII U-boats. Both the new types, however, were put into production prematurely and defects discovered during trials and teething troubles had prevented

them from becoming operational. The loss of the eastern Baltic ports and the heavy bombing of the western Baltic ports, together with mining of that area,

further delayed the long awaited offensive by the new-type U-boats. About six patrols were made by Type XXIII U-boats in the North Sea before the end of

the war. The immense effort put into developing Type XXI was a complete waste as it did not operate at all before the German surrender.

The Allies were forced, however, to develop countermeasures to the high speed U-boats. HMS Seraph, a British submarine, was converted so that she

could make 12 knots for a limited time and trials were conducted to develop new tactics for use against the high speed U-boats.

Three Type XVII-B U-boats with turbine drive were completed before the end of the war. These were built for experimental purposes to obtain information

on tactics and improvements for the Type XXVI U-boat, which was to be the perfect U-boat, incorporating all the advantages of earlier experience and the

extremely high speeds available with the Walter propulsion units. The high speed obtained from turbines using hydrogen peroxide fuel was of limited

duration and was only to be used in attacks or other emergencies. A diesel for cruising at Schnorchel depth and a small battery and electric motor for

quiet running were to be used for all other purposes. There was no expectation of ever operating these U-boats on the surface.

The Type XXVI U-boat was intended to be about 184 feet long and to carry a crew of 37 men. The maximum submerged speed on turbines was to be 24 knots

with an endurance of about 6 hours at that speed. Ten torpedoes were to be carried in four bow and six side torpedo tubes. Sound gear was to be used to

direct torpedo fire from a submerged position and all ten torpedoes could be fired in one salvo.

It should be stressed at this point that no Type XXVI U-boats were ever built and that no Type XXI U-boats ever operated at sea before V-E Day. The

conclusions developed in this history of World War II do not necessarily apply to these high submerged speed U-boats.

| 7.2.4 |

Sinkings of U-boats |

The average number of U-boats sunk monthly during this period was 18, slightly less than during the previous peak period. This decrease was due

primarily to the considerable drop in the average number of U-boats at sea. The total number of U-boats sunk during this 11-month period (June 1944

through April 1945) was 196, consisting of 161 German U-boats and 35 Japanese U-boats.

Over 80 per cent of the 148 U-boats sunk in the Atlantic were destroyed in the waters surrounding England, as 59 were sunk in the Biscay-Channel

Area, 35 in the North Transit Area-East, 14 in the North Sea, and 13 in the Northeast Atlantic Area. The other 27 Atlantic U-boat kills were divided

as follows: 7 in the Northwest Atlantic Area, 6 in the Barents Sea Area, and 14 in widely scattered parts of the remainder of the Atlantic, 9 of them

in the west Atlantic and five in the east Atlantic.

--77--

Surface craft displaced aircraft as the leading killer of U-boats during this period, as most of the German U-boats operated on Schnorchel. Allied

ships sank 92 U-boats alone (47 per cent of total) and another 15 (8 per cent of total) with the help of aircraft. Aircraft sank 57 U-boats (29 per cent

of total). As most of the U-boats operated in inshore waters, carrier-based aircraft played a smaller part during this last period accounting for only 14

of the 72 U-boat kills in which aircraft participated. Allied submarines sank 17 U-boats (9 per cent of total), most of them in the Pacific. The other 15

U-boats (7 per cent of total) were lost as a result of mines, marine casualties, and scuttling.

The quality of surface craft attacks reached its highest level during this last period as over 30 per cent of the attacks were lethal. This percentage

reached a high of about 50 per cent during the invasion period, when U-boats first started operating on Schnorchel. It dropped to about 20 per cent as

U-boats perfected their inshore tactics during the last quarter of 1944 and then increased again to about 30 per cent during the first few months of 1945,

as British escort groups learned how to deal with the bottomed U-boat.

| 7.3.1 |

From the U-boat's Point of View |

Some idea of the attitude of U-boat crews and officers during this last period may be obtained from statements made by prisoners of war. Toward the

end of 1943, many doubts and questions had arisen concerning the outcome of the war and the supposed superiority of German weapons. These doubts became

stronger when, despite the many promises of new weapons made by the U-boat Command, practically none were supplied and the U-boats' situation steadily

deteriorated. The former enthusiasm and confidence of the men in the power of their arms and in the competence of their leaders turned into a kind of

lassitude, and resulted in a mechanical execution of commands. The phrase "orders are orders" characterized the typical state of mind. The majority of

U-boat officer survivors expressed in no uncertain terms the opinion that the U-boat was no longer practicable as an offensive weapon in view of the

effectiveness of Allied antisubmarine measures at that time. Despite their state of mind, the U-boats fought to the very end of the war with discipline

unimpaired, and there were no signs of any collapse of the German Navy, such as occurred in 1918.

About 13 U-boats were sunk monthly in the Atlantic, slightly less than the previous figure of 16. The average number of U-boats at sea, however, had

declined to 39 from the average of 61 in the previous period. This meant that the average life of a U-boat at sea in the Atlantic was only three months,

even lower than the average life of four months in the previous period. Despite the use of Schnorchel and maximum submergence tactics, the U-boats found

operation in inshore waters just as hazardous as they had been at the beginning of the war when the U-boats had to give up close-in submerged operations.

The exchange rate in the Atlantic was about the same as in the previous period as only 6/10 of a ship (3300 gross tons) was sunk by the average U-boat

before it itself was sunk. U-boats operating in inshore waters where there was a heavy concentration of shipping were able to sink a little more shipping

per month at sea during this period but this was balanced by the higher loss rate suffered by them.

The tactics evolved by the Schnorchel U-boat toward the end of the war involved practically no surfaced operations. In transit, navigation was by dead

reckoning, radio-navigational fixes off the chain of "Electrasonne" transmitters and beacons, and also by echo sounder and periscope bearings of lights or

points of land. Schnorchelling was mostly at night, for only about four hours in each 24. When Schnorchelling, a U-boat kept all-around periscope watch day

and night, and constant meter-band GSR watch. Diesels were stopped once every 15 to 30 minutes to make an all-round hydrophone sweep. Once the U-boat was in

the patrol area, it was a recognized tactic to lie on the bottom of a convoy route and to come up only when hydrophone contact was established. For aiming

the torpedoes, the periscope was still virtually the only instrument available. Salvos of curly torpedoes were fired among the merchant ships, or else a

single acoustic torpedo at either the convoy or an escort. The usual methods of evading Allied counterattacks were either lying on the bottom, or else

proceeding at silent speeds of about 3 knots or less on electric motors.

The Schnorchel enabled U-boats to operate in the above manner in inshore areas. These U-boats would have met certain destruction, had it still been

necessary for them to surface periodically, for a few hours, to charge batteries. The problem presented by the

--78--

Schnorchel U-boat has been the chief concern of surface craft, whose main difficulty has been that of distinguishing between a bottomed U-boat and a

wreck. An extensive survey of wrecks in British waters helped considerably in solving this problem.

Schnorchel enabled U-boats to operate in inshore waters, but it did not enable them to achieve any significant results. Operational results during the

last two years of the war indicated that the standard U-boat, with or without Schnorchel, could not operate successfully against Allied antisubmarine

measures. It is important to realize, however, that the U-boat war was not decisively ended in May 1945. Germany had a fleet of about 120 Type XXI U-boats

read to start operations and was developing the Type XXVI U-boat. It is difficult to say whether the high submerged speed would have restored the advantage

to the U-boats and would have enabled them to inflict considerable damage on Allied shipping without suffering excessive losses.

| 7.3.2 |

From the Allies' Point of View |

The Allied and neutral nations lost about 114,000 gross tons of merchant shipping each month, from all causes, during this period. This was the lowest

average monthly loss of the war and about 25 per cent less than in the previous period. The construction of new merchant shipping averaged about 850,000

gross tons a month, slightly less than in the previous period. Consequently, there was a net gain of about 736,000 gross tons of shipping each month, or a

total increase during this period of about 8,000,000 gross tons in the amount of shipping available.

Of the 114,000 gross tons of shipping lost monthly from all causes, about 84,000 gross tons were lost as a result of enemy action. U-boats accounted for

56,000 gross tons a month, or about 67 per cent of the total lost as a result of enemy action. Monthly losses to enemy mines rose to 15,000 gross tons

(18 per cent of enemy action total) as Allied shipping moved close to the shores of Europe after the invasion. Losses to enemy aircraft dropped to 8000

gross tons (9 per cent of enemy action total) a month. The other 5000 gross tons (6 per cent of enemy action total) sunk monthly were lost as a result of

surface craft attack and other enemy action.

By the end of this period, Allied armies had overrun Germany, and the surrender came on May 8, 1945. The Allies had defeated the U-boats in 19-13 and

had succeeded in keeping them ineffective thereafter. It was both an offensive and defensive victory as the average U-boat's lifetime at sea in the Atlantic

was only three months and it sank only about onehalf ship before it itself was sunk. The Allies were not able, however, to destroy the enemy's U-boat fleet

without invasion, as the enemy's construction program had been able to replace all losses.

The war seems to have demonstrated that the standard U-boat could not operate on the surface against strong Allied air power. It Should be remembered,

however, that the U-boats did not operate, to any large extent, with a reliable radar or search receiver that could detect Allied planes at long range.

Denied the surface of the sea, the standard U-boat, with limited submerged speed and endurance, could not operate effectively against strongly escorted

Allied convoys.

The German solution to this problem was the development of the Type XXI and Type XXVI U-boats, which had much higher submerged speed and endurance and

could operate underseas en-tirely. These U-boats would be relatively as safe from air attack as were the standard Schnorchel U-boats and would be much

safer from surface craft attack, due to their high submerged speeds. They would be much more effective against convoyed shipping as their high speed would

enable them to approach and keep up with Allied convoys without surfacing. We cannot determine without extensive trials and exercises with high submerged

speed U-boats just how much more effective than the standard types they would be. We cannot now determine quantitatively whether they would be 50 per cent

better, or ten times as good. From the history of World War II, however, we may conclude that these new U-boats would have to be about eight times as

effective in sinking ships and about four times as safe at sea as were the Schnorchel U-boats in the last period, in order to achieve the same results as

were achieved by the U-boats during their peak period, January 1942 through September 1942.

--79--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (6) *

Next Chapter (8)

Footnotes

Transcribed and formatted for HTML by Rick Pitz for the HyperWar Foundation