Chapter III

Allied Arrangements

(a) Allied Command Relations

The entire Pacific area had been designated as an area of U.S. strategic responsibility. This area had been divided into three large areas: the southwest Pacific, the southeast Pacific, and the Pacific Ocean; the latter being further subdivided into the North, Central, and south Pacific areas.

The boundaries of the south Pacific area and those of the south Pacific area [sic] are of importance in the study of the Battle of Savo Island as it was within these area that the operations in connection with this action were confuted. The pertinent portions of the northern and eastern boundaries of the southwest Pacific area were from Long. 130 degrees East along the Equator to 159.degrees East, thence South.* The South Pacific area was bounded on the west by the Southwest Pacific area and on the north by the Equator.

The Pacific Ocean Area was under the command of Commander-in-Chief (CINCPOA) who had directed, among other tasks, to--

-

Protect essential sea and air communications

-

Prepare for execution of major amphibious offensives against positions held by Japanese initially to be launched from South Pacific and Southwest Pacific areas.*

CINCPOA was charged with the direct exercise of command of combined armed forces in the North and Central Pacific Area (COMSOPAC) who exercised command of combined forces which were at any time assigned to that area. The Commander South Pacific Area was also Commander South Pacific Force. (COMSOPACFOR).Under COMSOPACFOR were all of the naval forces of the Allied nations in the South Pacific Area.

The tasks listed above for CINCPOA were assigned, somewhat modified by that commander, to COMSOPAC for execution. These modifications more specifically delineated COMSOPAC'S responsibilities. The tasks. were:

-

Protect the essential sea and air communications.

-

Prepare to launch amphibious offensives against positions held by Japan.**

*Joint Directive, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, War Diary COMSOPACFOR July 1942

(COMINCS to CINCPAC 022100 July 1942).

**Organization of South Pacific Area, Lecture by Capt. T.H. Robbins,Jr., USN,

Army-Navy Staff College, January 13th, 1944.

--15--

The Southwest Pacific area was under the command of a Supreme Commander who had been directed, among other tasks, to:

-

Check enemy advance toward Australia and its essential lines of communication by destruction of enemy combatant troop and supply ships, aircraft, and bases in . . . the New Guinea, Bismarck-Solomon Island region.

-

Support the operations of friendly forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas and in the Indian Theater.

-

(c) Prepare to take offensive.*

The Supreme Commander Southwest Pacific Area (COMSOWESPAC) had as his naval commander a United States naval officer who was designated Commander Southwest Pacific Force (COMSOWESPACFOR) and who was vested with all powers customarily granted to the Commander-in-Chief of Fleets. Under this commander were all of the naval forces of the Allied Nations in the Southwest Pacific Area.** It is of interest that when task forces of the Southwest Pacific Area operated outside that area, coordination with forces in the new operating area was to be effected by the Joint Chiefs of Staff or by the combined Chiefs of Staff as appropriate.***

CINCPOA was Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who on May 8th had assumed command of all land, sea, and air forces in the Pacific Ocean Area except the land defenses of New Zealand. His headquarters were at Pearl Harbor. COMSOPAC was Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, who on June 19th had assumed command of the South Pacific Area and the South Pacific Force. His administrative headquarters were at Auckland, New Zealand; his operational headquarters were established on board the ARCONNE at Moumen on August 1. COMSOPAC was empowered to appoint commanders of task forces in his areas. COMSOWESPAC was General Douglas MacArthur, who had assumed command of that area on April 18th. His headquarters were at Brisbane, Australia.

Thus it is evident that unity of command for military operations in the South Pacific Area existed at this time. COMSOPAC was in command of all operations within this area. This was a marked improvement over the command organization which had been in existence at the Battle of the Coral Sea just three months earlier wherein COMSOWESPAC had not been in command of the naval forces operating within this area. Unity of command for this operation was effected by moving the boundary between the Southwest Pacific and the South Pacific areas from 165 degrees E. Longitude to 159 degrees Longitude-a change which pleased Tulagai, Guadalcanal and other islands

*SecNav Secret Letter (SC) A16-3(28) April 20th, 1942, encl. (A).

**SecNav Secret Letter (SC) A16-3(28) April 20th, 1942. page 1.

***Ibid., enclosure (A).

--16--

Allied Command Relations on 8 August 1942

--16a--

the Battle of Savo Island was fought, all operations within these areas were under COMSOPAC.

Any support rendered to COMSOPAC by COMSOWESPAC or vice versa was to be by cooperation.

The command of combined operations with Australian forces was as follows: If carrier units were involved, the senior American naval officer would be in command because of the nature of carrier operations; otherwise when the naval forces of the two powers were operating together and no carrier operations were involved, the senior officer of either power would be in command.**

Such were the command organizations for the Pacific, South Pacific and Southwest Pacific areas. However, in order to understand more clearly the various factors which culminated in the Battle of Savo Island it appears wise at this time to explain the command situation which . . . [existed in] . . . the South Pacific Area with relation to its newly assigned mission--to seize and occupy Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagai, and adjacent positions in order to assist in seizing and occupying the New Britain-New Ireland Area.* This mission was designated as Task ONE.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff directed CINCPAC to designate the task force oommander for this task. However, COMINCH gave CINCPAC little discretion in the matter, for he stated to CINCPAC, "It is assumed Ghormley will be made task force commander at least for Task ONE which he should command in person in the operating area." He stated in the sam e dispatch that the commander for Task ONE "should also have a conference with MacArthur."* As a consequence CINCPAC on July 9th desisgnated COMSOPACFOR as the Task Force Commander for Task ONE and directed him to exercise strategic command in person in the operating area which was interpreted to be initially the New Caledonia-New Hebrides Area. CINCPAC at Pearl Harbor retained over-all command.***

The Joint Chiefs of Staff directed that direct command of the tactical operations of the Amphibious Forces was to remain with the naval task force commander; that COMSOWESPAC was to support the operations of Task ONE by providing for the interdiction of enemy air and naval activities westward of the operating area, which was evidently interpreted as westward of the South Pacific Area; and that COMSOWESPAC was to attach the necessary naval reinforcements and land-based air support.* CINCPAC advised COMSOPACFOR that as a consequence , COMSOWESPAC was making available

*Joint Directive, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, War Diary COMSOPACFOR July 1942, (COMINCH to CINCPAC, 022100 July, 1942).

** War Diary CINCPAC, April 16th, 1942.

***Letter of instructions CINCPAC, Serial 0161W July 9th, 1942.

--17--

certain surface and air forces and authorized COMSOPACFOR to apply directly to COMSOWESPAC for any additional forces required.*

In accordance with his designation as Commander for Task ONE, COMSOPACFOR issued an Operation Plan wherein he formed two task forces to carry out his mission. One of these task forces he designated as TF 61, the Expeditionary Force; the other as TF 63 , the Shore-Based Aircraft. TF 61 was composed of three lesser task forces; one, the Air Support Force, consisting of three Pacific Fleet carrier task forces, TFs 11,16 and 18; one, the naval forces transferred by COMSOWESPAC and termed TF 44; and one, the South Pacific Amphibious force, TF 62. TF 63 was composed of all land-based and tender-based aircraft attached to the South Pacific force, and of the aircraft temporarily attached and basing on islands in the South Pacific Area,. He designated Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, USN, CTF 11, who was commander of the Pacific Fleet Striking Forces, a force consisting entirely of carrier task forces, as CTF 61 and Rear Admiral John Sidney McVain as CTF 63. He directed that coordination between these two forces was to be through cooperation, although he directed CTF 63 to supply aircraft support to CTF 61 on call.**

CTF 61 then issued an Operation Plan in which he assigned command of the Air Support Force (61.1) to CTF 18 as CTG 61.1 in the Wasp, and command of the Amphibious Force (61.2) to the Commander South Pacific Amphibious Force, CTF 62 in the McCawley. He retained command of TF 11 which for this operation became TG 61.1.1 and continued to fly his flag in the Saratoga. To 61.2 was composed of the following: TF 62; three heavy cruisers, one light cruiser and six destroyers from the South Pacific Command; and TF 44 less one heavy cruiser.*** TG 61.2 thereafter employed the designation TF 62 and organized his command accordingly.

This designation of CTF 11 as the Commander Expeditionary Force with the title CTF 61 was a necessary requirement of this operation. This was because CTF 61 was the only combat trained carrier task force commander within the command, and it was felt that it was more important to retain him within the carriers than to give him freedom of action to go where he desired. This kept him far away from the scene of action.

In this connection experience has shown that it is generally wiser for the Supreme Tactical Commander to place himself within the amphibious force during landing operations and within the covering force if action with enemy surface forces is imminent. This enables him to keep himself continuously informed of the constantly changing situation and permits him to employ his communications freely once contact with the enemy has been made. This was the practice in later operations such as OKINAWA where the fleet commander was in one of the older cruisaers. He was thus

*Letter of Instructions CINCPAC, Serial 0151W, July 9th, 1942.

**COMSOPACFOR Opera t ion Plan 1-42 Serial 0017, July 10th, 1942.

***CTF 61 Operation Order 1-42, July 28th, 1942.

--18--

able to move freely to the position of paramount interest without appreciably

weakening the strength of the force to which he was nominally assigned*.

It will be noted from the above that CTF 61 was also CTG 61.1.1 as well as Commander Striking Forces Pacific Fleet and CTF 11; that CTF 62 was also CTG 61.2 and that many of the other commanders bore several designations, most of which had no connection with the assigned operation. Such a multiplicity of diverse titles could not have but been confusing to the commanders concerned, as well as to the subordinate commanders throughout whatever echelon.

(b) Information Available to Allied Commander

COMSOPAC realized from indications that the Japanese wee planning to extend, to the South and Southeast, the control then held on most of New Guinea-New Britain-Northern Solomons Area, and were therefore consolidating and improving their positions there.**

He knew the location of most, if not all, of the Japanese airfields and seaplane bases in the theater of operations and had daily reconnaissance information of their employment. He knew that the Japanese were developing three airfields, one at Bunga Point, Guadalcanal Island; one at Kieta, Bougainville Island, and one at Buka Passage, Buka Island. He further knew that the Japanese had seaplanes a Rabaul; Rekata bay, Santa Isabel Island; Faisi, Shortland Islands; Kieta, Bougainville Island; Gizo Island; Tulagi harbor, Florida Island; and Buka Passage.**

He believed that all three airfields were in satisfactory operating condition and that Kieta, in particular, was receiving personnel and equipment.** Actually the Buka airfield was in an advance state of construction, being completed on August 8th; the construction of the Kieta airfield had been stopped, presumably in July, and the airfield at Lunga Point was well advanced, being completed on August 6th.

He believed that there were four heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 6 and three light cruisers of Cruiser Division 18 in the Rabaul-Kavieng Area.*** This was approximately correct. However, there but two light cruisers there--the additional cruiser was a large heavy cruiser, the Chokai.

* Statement by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN, CINCPAC's Chief of Staff at the time to Commodore Richard W. Bates, USN (Ret.), Head of Dept. of Analysis, Naval War College on June 1st 1949.

** COMSOPAC Serial 0017 July 16th, 1942 Appendix III and CTF 62 Operation Plan A3-42-Ser.0010 Annex EASY, July 30th, 1942, Part (1).

*** CINCPAC Serial 0151W to COMSOPAC, July 9th, 1942, Reference "C" Information on Enemy Forces and Positions in SOWESPAC Area up to July 10th, 1942.

--19--

He believed that there were thirteen destroyers of DESRONs SIX and THIRTY-FOUR in the area.* this was partially correct in that there were eight rather than thirteen destroyers. All eight destroyers were from DESRON SIX and all appeared to have been assigned to escort duty.

He believed that there were about fifteen submarines in the Bismarck-New Guinea-Solomons Area.* This was markedly incorrect as there were but ten submarines in the entire Outer South Seas Area at the time of landing. Of these, but two, from SUBRON SEVEN, appear to have been in the Bismarck-New Guinea-Solomon Area.

He knew quite correctly that there were two Av's and three or four XAV's in the Rabaul area.

He knew that the Japanese air strength in the Bismarck-New Guinea-Solomons Area was about sixty VF, sixty VB and thirty VP planes--a total of 150 on July 30th. This estimate, at least for August 6th, was about 30% too high, due perhaps in part to losses suffered from Allied air strikes on Rabaul and on operational losses. Actually there were present on August 6th about forty-eight VF, forty-eight VB and fifteen VP. He believed that about eight of the above fighters, equipped with pontoons as float planes, and about seven to ten of the patrol planes were operating in the Tulagi area.** His estimate of the planes in the Tulagai area was reasonably correct.

He realized that the Japanese capability of striking with land-based air power at Allied Forces in the Guadalcanal Area was real and that attacks could be expected.

He knew that the strength of the striking forces which the Japanese could bring to bear against his operations in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi Area had been greatly decreased by the Japanese losses during the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway.*** However, he realized that there could well be still strong Japanese forces in or near the area.

He was aware of the air strength in the Marshall-Gilbert Islands Area and in the Truk-Ponape Island area, and the Japanese capability resulting therefore, of quick reinforcement of the Bismarck-New Guinea-Solomons Area.**** It eventuated that the reinforcement was not accomplished until after the Battle of Savo Island.

*CTF 62 Op. Plan A3-42, Serial OC10, Annex BASY, July 30th, Part(1), para. (c).

**Ibid., para. (d).

***CINCPAC Serial 0151W to COMSOPAC, July 9th, 1942, para 2.

****CINCPAC Serial 0151W to COMSOPAC, July 9th, 1942, Reference "C".

Information on enemy Forces and Positions in SOWESPAC Area up to July 10th, 1942.

--20--

He realized that despite the Midway and Coral Sea losses, a definite Japanese capability existed of supporting Japanese land-based air with carrier-based air operating from carrier task groups. His air searches were therefore designed to discover such carrier forces before they could reach effective

striking positions.* This latter concept seems to have been the greatest motivating consideration in all of the planning in the conduct of searches in both SOPAC and SOWESPAC and in the deployment of forces. Actually there were no Japanese carrier task groups within the area and none appeared until the Allied beachheads had been reasonably secured.

Finally, he knew that the existing Japanese reconnaissance operated in depth. He therefore felt that surprise was improbable.** Actually, although Japanese searches and reconnaissance did in fact operate in depth, there appear to have been no Japanese searches or reconnaissance on the day of the Allied approach, so that the Allies did, in fact achieve surprise.

(c) Allied Land and Tender Based Aircraft

(1) South Pacific (SOPAC)

The land and tender-based aircraft in the South Pacific Area has been organized as has been pointed out earlier into a command under Rear Admiral John Sidney McCain, U.S.N. (COMAIRSOPAC). The units of this force were employed chiefly for the protection of SOPAC bases and the essential sea and air communications. AIRSOPAC included Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Royal New Zealand Air Force units.

The administration of these units was divided. As regards training in particular, COMAIRSOPAC was charged with the training of Navy and Marine Corps aviation, whereas the Commanding General of U.S. Army Forces in the South Pacific Area (COMGENSOPAC)--a command assumed by General Millard F. Harmon, U.S. Army Air Corps on July 26, 1942--was charged with the training of all Army Air Corps units. The Royal New Zealand Air Force units present in SOPAC Area were under the unity of command structure of the particular base at which they were located, and this placed them under a U.S. Army officer in every case.

The tactical operations of all SOPAC aircraft for the support of the Allied amphibious offensive which led to the Battle of Savo Island were placed under the command of COMAIRSOPAC whose tactical title was Commander Task Force 63 (CTF 63). CTF 63 availed himself of the advice of COMGENSOPAC and, owing to the wide dispersion and dissimilar composition

* CTF 61 Dispatch 290857, July, to CTF 63.

** COMSOPAC-COMSOWESPAC Joint Dispatch 081017, July 1942, which is Part Four of Dispatch 081012, July 1942.

--21--

of the air organization, allowed the latter a certain amount of operational discretion.

Table 2 shows a tabulation (by numbers and locations) of the planes available to CTF 63 on August 6th--the day prior to the initial American landings in the Solomons, and the day that the Allied Expeditionary Force approached within range of the Japanese land based aircraft. Of all the planes listed in Table 1, the only ones suitable for search and attack missions over and beyond the objective were the Army B-17s and the Navy PBY-5s. The limiting ranges of the other aircraft restricted their roles to defense of bases, air coverage for surface units within range of those bases, and routine anti-submarine patrols. For this reason theses aircraft did not participate in operations directly involved in the Battle of Savo Island, and are dropped from further discussion.

In the Solomons offensive, the B-17 was the better search plane over Japanese held positions in the islands where enemy fighters might be encountered. The B-17 had a speed advantage over the PBY-5--30 knots faster cruising, and 45 knots faster maximum speed. The B-17 had better combat qualities as a result of its self-sealing tanks and its 8 flexible 50-calibre gun mounts. As a bomber, the B-17 was effective only to about 600 miles radius. This short range made it necessary to operate it from the furthest advanced airfield, and placed an urgency upon CTF 63 to complete the airfield at Espiritu santo by August 1st.

The PBY-5 was better suited to cover the wide ocean areas through which Japanese surface units could approach the target area, and in which Japanese fighters were not likely to be encountered. The advantage of the PBY-5 over the B-17 in these areas was due to its greater range - in the ratio of 3600 miles to 2000 miles for economical cruising , and in the ratio of 800 miles to 600 miles radius as a bomber.*

Both the PBY-5 and the B-17 were equipped with radars of the ASE model; but little advantage was gained from these radars other than navigational assistance. These radars provided a search beam of about 15 degrees spread normal to the line of flight on both sides of the plane, designed to be effective to about 25 miles range. A homing beam was also provided, ahead of the plane to an effective range of about 15 miles. Since the pilots did not consider the lateral search beams reliable but placed their faith in the homing beam ahead, these early radars provided little more than the equivalent of the reliable limits of human vision in clear weather. They did, however, make it possible to conduct night searches in clear weather as effectively as day visual searches. Since rain squalls showed up on the radar scopes much like "sea return", these radars were about 50% effective in bad weather, day or night.** Their

*Airplane characteristics, Naval War College, June 1942.

**Tactical use of Radar in Aircraft, Radar Bulletin No. 2, COMINCH July 29th, 1942.

--22--

Table 2

Disposition of Allied Shore and Tender-Based Aircraft

As of 2400, August 6, 1942

| Name |

11th

Bombardment

Group |

69th

70th

Bombardment

Sqdns |

67th

68th

70th

Pursuit

Sqdns |

VP Sqdns

11, 14 & 23 |

R.N.Z.A.F.

Units |

Marine Corps

Squadrons |

Navy

Inshore

Patrol

Sqdns

VS1, D14 |

Total

Planes |

VMF

111

&

212

VMO 251 |

VMO

151 |

| |

B-17 |

B-26 |

P-39 |

PBY-5 |

Hudson |

Singapore |

Vincent |

F4F |

SBC |

OS2U |

|

| Espiritu |

*5 |

|

|

**10 |

|

|

|

***3 |

|

3 |

21 |

| Efate |

****5 |

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

13 |

|

3 |

25 |

| New Caledonia |

10 |

10 |

38 |

2 |

6 |

|

|

16 |

|

3 |

85 |

| Nandi |

12 |

12 |

17 |

6 |

12 |

3 |

9 |

|

|

|

71 |

| Ndeni |

|

|

|

*****6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

| Samoa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

17 |

10 |

45 |

| Tongatabu |

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

30 |

| Total |

32 |

22 |

79 |

28 |

18 |

3 |

9 |

50 |

17 |

25 |

283 |

* 1 of 6 B-17s of 98th Squadron lost east of Espiritu Santo due navigational error.

** 1 of 11 PBYs failed to return from search Sector III.

*** 1 of 4 F4F-3A of VMF-212 crashed at sea August 6th. Replaced from Efate.

**** 2 of 7 B-17s of 26th Squadron lost previously, one August 4th, one August 5th.

***** 1 of 7 PBYs lost at sea August 6th.

--22a--

Chief value to pilots was derived from their ability to pick up land about sixty miles at sea, depending on the altitude of the terrain, and assisted greatly in fixing their navigational positions

The total of thirty-two B-17s in the South Pacific Area on August 6th were assigned to the four squadrons (the Twenty-Sixth, Forty-Second, Ninety-Eighth and Four Hundred and Thirty-First Bombardment Squadrons) of the ELEVENTH Bombardment Group.* The ELEVENTH Bombardment Group had been formed in Hawaii in mid-July and designated as the Mobile Air Force, Pacific Ocean Area. As such, its disposition anywhere within the Pacific Ocean Area rested with the discretion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who determined upon its employment in the South Pacific Area in support of the Allied offensive in the Solomons.**

The disposition of these aircraft on August 6th (Table 1) was the deployment ordered for Task ONE in the Solomons by CTF 63 Operation Order 1-42 as follows: five B-17s of the Twenty-Sixth Bombardment Squadron at Espiritu Santo; ten B17's of the Ninety-Eighth Bombardment Squadron at Efate and five B-17s of the Forty-Second Bombardment Squadron on New Caledonia at Koumac and Plaines Des Gaiace airfields; and a reserve of twelve B-17s of the Four Hundred and Thirty-First Squadron at Nandi, Fijis. This disposition was not hard and fast, and heterogeneous groupings of planes resulted from the rotation forward of reserve aircraft replacements for damaged and lost B-17s, and the flexibility with which airfields could be employed in case of bad weather emergencies.

The twenty-eight PBY-5s in the South Pacific were disposed on August 6th (Table 1) as follows: six planes shore based at Nandi, Fijis; four planes shore-based at Havannah Harbor Efate; two planes shore-based at Ile Nou, Noumea; ten planes based on the tender Curtiss in Segond Channel, Espiritu Santo; and six planes based on the McFarland at Graciosa Bay, Ndeni. The aircraft tender, Mackinac was en route on August 6th from Noumea to Maramasiko Estuary to establish an advance seaplane base to which nine PBY-5s would be moved up on August 7th.

(2) Southwest Pacific (SOWESPAC)

The land-based aircraft in the southwest Pacific Area included units of both the U.S. Army Air Corps and the Royal Australian Air Force. This combined organization was called Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific. Its headquarters were in Brisbane, Australia, in the same building as the headquarters of the Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific. Major General George Kenny, Air Corps, U.S. Army assumed command of the Allied Air Forces on August 4th--only three days before the Allied amphibious landings in the Solomons.***

* COMAIRSOPAC War Diary, July 1942 also U.S. ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive.

** U.S. ARMY IN WORLD WAR II, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, page 27.

*** Army Air Forces in the War Against Japan 1941-1942, page 134.

--23--

This air command was divided into four sub-area commands, but only those units of the Allied Air Forces, North Eastern Area with headquarters at Townsville, Australia,* were involved in operations in New Guinea and in the Bismarck designed to checks the advance of the Japanese.

The 19th Bombardment Group, based at Townsville had been designated as a Mobile Air Force in July--a Southwest Pacific counterpart to the 11th Bombardment Group the Pacific Ocean Area. These two Mobile Air Forces in the Pacific Theater were disposed on August 6th against the Japanese advance south of the Equator. The 19th Group, with approximately the same strength as the 11th Group in SOPAC but with rarely more than twenty B-17ís in commission,** was the chief offensive weapon against the Japanese base at Rabaul. His attack groups suffered an attrition rate over Rabaul of about 20% per month.***

In order to reach Rabaul with B-17s from Townsville, Commander North Eastern Area had to stage through the advanced air base at Port Moresby. His bombers usually avoided Japanese air attacks on Port Moresby by arriving after dark, and preparing for the next day's mission during the night. They took off in the early morning for Rabaul, and followed a route along the New Guinea coast for 40 or 50 miles to gain sufficient altitude to cross the Owen Stanley Mountain range at approximately 7000 feet. They discovered in these operations that the equatorial weather proved to be as dangerous as enemy fighters.****

Commander North Eastern Area had pushed the construction of additional fields in the vicinity of Port Moresby in order to obtain dispersal of his bombers and to base defending fighters in the vicinity to ward off Japanese air attacks. By August 6th, he was able to base his B-17s at Port Moresby, under the protective cover of about forty P-39s of the 35th Pursuit Group.

He had also pushed the construction of the Fall River field at Milne Bay, New Guinea. This field would not take heavy bombers but was useful for reconnaissance planes. On August 6th, he moved a detachment of five Hudsons from the 32nd General Reconnaissance Squadron of the Royal Australian Air force to the Fall River field from Port Moresby. This detachment was to reconnoiter the Northwestern Solomons thereafter.***** He provided for the air defense of Fall River by basing there the 75th and 76th R.A.A.F. Fighter Squadrons equipped with P-40 aircraft.

* Headquarters, Allied Air Forces--Operations-Instructions No. 18, July 31st, 1942.

** Army Air Forces in the War Against Japan 1941-1942, page 124.

*** THE ARMY AIR FORCES IN THE WORLD WAR II, Plans and Early Operations, Note 27, page 723.

**** Ibid., page 480.

***** Letter from Major-General Harry J. Maloney, U.S.A., Chief, Historical Division to President Naval War College, October 11th, 1948.

--24--

Other air groups in the North Eastern Area were: the 3rd Bombardment Group (17 B-25ís) and the 22nd Bombardment Group (about 54 B-26s total, but only 26 planes available). Since these groups were employed on shorter range attack missions incident to the SOWESPAC operations and did not contribute directly to the support of the SOPAC offensive operations, they will receive no further attention.*

(d) Allied Search and Reconnaissance

(1) South Pacific (SOPAC)

CTF 63 planned the Allied searches from South Pacific bases to detect any enemy interference in that portion of the Coral Sea which lay east of Longitude 158 degrees East. He designed his air searches to cover both the Allied operations within the Tulagi-Guadalcanal Area and the Japanese approaches thereto from the northward as far as the range of his search aircraft would permit. A primary objective of these air searches was the detection of any Japanese carrier striking group which might enter the South Pacific from the direction of Truk or the Marshall Islands.**

In order to extend the range of his searches to the north as the Allied Expeditionary Force moved forward to its objective, he deployed his seaplane tenders progressively forward to establish more advanced bases for his seaplanes. This deployment consisted of moving the Curtiss with two patrol planes of VP-23 from Noumea to Segond Channel, Espiritu Santo, where search operations were commenced on August 5th; then of advancing the McFarland with seven patrol planes (five PBY-5s of VP-11 and two of VP-14) from Noumea to Graciosa Bay, Ndeni, where search operations were commenced on August 6th; and finally, after the landings at Tulagi and Guadalcanal, of advancing the Mackinac from Noumea to Marmasike Estuary, Halaita Island. The MACKINAC provided CTF 63 with a seaplane base in the southern Solomons as far north as Tulagi. Search operations were commenced from Marmasike Estuary on August 6th, employing the nine remaining patrol planes of VP-23 (one of the original ten had been lost on August 6th) which had been operating from the Curtiss in Espiritu Santo. The Curtiss, in turn, received two patrol planes advanced from Havannah Harbor, Efate, and placed in commission one plane of VP-11 which had been undergoing repairs in the Curtiss, and thereafter supported three search planes.

CTF 63 had deployed his seaplane tenders in such manner that the rear-most one, the Curtiss, served as a centrally located command center for Task Force 63. It provided headquarters for CTF 63, COMGENSOPAC, the 11th Bombardment Group (CTG 63.2), and the Curtiss search detachment (CTG 63.3). It also served as a communications ship for the air operations of the field at Espiritu Santo.

* THE ARMY AIR FORCES IN WORLD WAR II, Plans and Early Operations, pages 478, 479, 480.

** CTF 61 Dispatch 290857, July 1942.

--25--

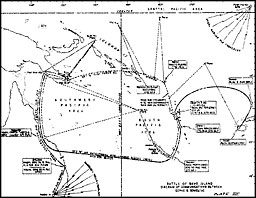

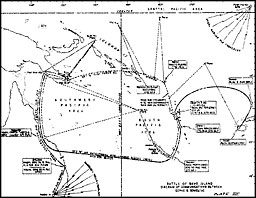

CTF 63's land-based searches were flown by seaplanes based ashore at Nandi, Fiji, and by B-17's located at the airfields of Espirutu Santo, Efate, and Koumac (New Caledonia). The B-17s were employed in Sectors I and II. As can be seen from Diagrams "B","C", and "D" these sectors existed over the southern Solomons where Japanese fighter aircraft were to be expected. CTF 63's employment of the B-17s over the islands and the PBY-6s over the open ocean exploited the advantages of each type, as analyzed in the previous section.

On August 6th, the day before the Allied Expeditionary Forces reached the Tulagai-Guadalcanal target area., CTF 63 conducted the searches shown on Diagram "B". At sunrise, planes took off to search to the following ranges: Sector II, 750 miles from Espiritu Santo; Sector IV, 630 miles from Efate; Sector VI, 700 miles from Nandi. Sector I, the range of which was to be 800 miles from Koumac, was not searched, probably because of bad weather. All other sectors were reported searched with negative results.

At about noon, August 6th, additional patrol planes took off to search Sector III to 700 miles range from Espiritu Santo and Sector V to a range of 650 miles from Ndeni. CTF 63 was complying with the request of CTF 61 that the planes searching Sectors III and V on August 6th arrive at the outer limit of search at sunset, and search the return leg by radar.** These searches were so timed as to prevent the possibility of Japanese striking groups approaching undetected from Truk to the outer limits of Sector V, or from the Marshalls to the outer limit of Sector III by sunset August 6th, from which positions they could advance during darkness to launch an air attack on the Allied Amphibious Force just as it reached its objective at sunrise on August 7th.

The searches in Sectors III and V were reported searched with negative results with the exception that no report was received from the plane searching the western-most subsector of Sector III, which plane failed to return.***

The basic problem of the Solomons offensive as visualized and enunciated by COMSOPAC was: "the protection of surface ships against land-based aircraft during the approach, the landing attack, and the unloading" at the target area.**** He had assigned to CTF 63 the task: "cover the approach to, and operations within the Tulagai-Guadalcanal Area by search. Execute air attacks on enemy objectives as arranged with Commander Expeditionary Force (CTF 61). Render aircraft support on call". **** Consequently, CTF 63's searches quite properly were made to support CTF 61, and to permit the concurrent employment of South Pacific aircraft for

* War Diary CTF 63 August 6th, 1942

** CTF 61 Dispatch 2909857, July 1942

*** War Diary CTF 63, August 6th, 1942.

**** COMSOPACFOR Dispatch 112000, July 1942 addressed to COMINCH, CINCPAC, AND COMSOWESPAC.

***** COMSOPAC Operation Plan No. 1-42, July 16th, 1942.

--26--

attack missions against the Japanese. With this double support role, CTF 63 conducted but one search of his sectors daily.

CTF 63's searches were not fully effective in providing the protection to the Expeditionary Force which COMSOPACFOR considered so paramount, and the cooperation of SOWESPAC land-based air units was necessary. For this reason the Joint Chiefs of Staff had directed that COMSOWESPAC would interdict enemy air and naval activities westward of the operating area, and CINCPAC had authorized COMSOPACFOR to discuss such operations* directly with COMSOWESPAC. As a consequence, COMSOPACFOR directed CTF 63 to make the arrangements with COMSOWESPAC relative to the coordination of aircraft scouting.**

(2) Southwest Pacific (SOWESPAC)

SOWESPAC search and reconnaissance missions conducted in the North Eastern Area prior to August 5th were all flown from Port Moresby. The searches covered the approaches to Milne Bay and to Buna. The reconnaissance missions took in the Japanese installations at Lae, New Guinea, and those around New Britain and New Ireland. These search and reconnaissance flights were chiefly in support of the operations of SOWESPAC in flights were chiefly in support of the operations of SOWESPAC forces in New Guinea.*** Commander Allied Air Forces, North Eastern Area had conducted but one reconnaissance flight in the Solomons during this prior period -- he reconnoitered the Tulagi-Guadalcanal Area on August 1st,*** the day the Allied Expeditionary Force departed from the Fiji Islands.

It was on August 5th that SOWESPAC air units began their operations to support the South Pacific offensive. COMSOWESPAC had previously arranged with COMSOPACFOR that his air forces in the North Eastern Area would coordinate their operations to assist the offensive in the South Pacific by searches commencing on August 5th (D-2 Day) and extending through August 11th (D+4 Day). SOWESPAC searches would extend to the limits of range of the aircraft employed. They would cover the water areas which lay to the southeast of a limiting line drawn from Madang (New Guinea) to the Kapingamarangi Islands and northwest of another limiting line extending from Tagula Island to the easternmost point of New Georgia. The eastern limit of his searches was the 158th meridian of East Longitude, extending northward from New Georgia. Commencing on August 5th, SOWESPAC aircraft were prohibited from operating east of 158°-15'(E) between the Equator and Latitude 150°(S) missions were requested by COMSOPACFOR.****

* CINCPAC ltr.of Instructions to COMSOPAC, July 9th, 1942, Serial 0151W, page 3.

** COMSOPAC Operation Plan No. 1-42, July 16th 1942.

*** Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific, Reconnaissance Reports for August 1st-5th, 1942 inclusive.

**** COMSOWESPAC Dispatch 191034, July 1942.

--27--

By referring to Diagram "B", it can be seen that the area of SOWESPAC air searches covered the Bismarck and Solomon Seas and the Pacific Ocean approaches to these waters. COMSOWESPAC gave instructions that the entrances to the Coral Sea, from the north and from the east, were to be given particular attention by his search planes.

The eastern limit of SOWESPAC searches was determined by mutual agreement between COMSOPACFOR and COMSOWESPAC. CTF 63 had suggested to COMSOPACFOR that SOWESPAC aircraft be requested to search west of 1580 East Longitude.* It is presumed that CTF 63 preferred to extend his own searches as far as possible to support the operations of the Allied Expeditionary Force, since he had been charged by COMSOPACFOR with the responsibility of providing (and arranging with SOWESPAC) for adequate coverage. Certainly he could be more assured of receiving contact reports from planes under his own control then from SOWESPAC planes which were merely cooperating. CTF 63 informed COMSOPAC that his own searches were disposed to isolate the Coral Sea east of Longitude 158°(E),* and that for increased effectiveness his searches overlapped that meridian to the westward by an average of 120 miles.* COMSOPACFOR informed COMSOWESPAC of CTF 63's plans for air searches and suggested the eastern limit of 158° East for SOWESPAC searches.** COMSOWESPAC concurred in this suggestion.*** The reason for his acquiescence to the penetration of the Southwest Pacific Area (the eastern boundary of which was 159° East Longitude) seems to have been revealed in his dispatch to COMSOPAC a week earlier, wherein he had pointed out that: "all available aviation in this area is subject to actual limitations of range. . . ."****

On August 5th, five Hudsons of the R.A.A.F. 32nd General Reconnaissance Squadron, based at Port Moresby, reconnoitered Buka, Mieto and Bougainville Srait, and then returned to base thereafter on the recently constructed firld at Fall River in Milne Bay.***** On succeeding days, the Hudsons searched an area extending through the northern Solomons as far south as the easternmost tip of New Georgia Island, which area was referred to as Reconaissance Area B.

Commander Allied Air Forces, North Eastern Area, also initiated Reconnaissance Areas C,D, and E on August 5th. Each of these areas were searched on August 5th and subsequent days by one B-17 (or one LB-30, an armed air transport version of the B-24) operating from Port Moresby.*** The geographic boundaries of these reconnaissance areas are not known definitely, but by plotting the time and position of each contact reported, it has been possible to approximate the tracks of the searching planes on Diagrams "B", "C", "D", and "E". Recconnaissance Area C appear to have

*COMSOPAC (CTF 63) Dispatch 220737, July 1942 addressed to COSOWPAC

** Dispatch 230250 , Juy 1942, addressed to COMSOPAC

*** COMSOPAC Dispatch 260955, July 1942, addressed to COMSOPAC.

****COMSOWESPAC Dispatch 191034 July 1942 addressed to COMSOPAC.

***** Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific, Reconnaissance Report for August 6, 1942

--28--

extended from Vities Strait along the south coast of New Britain past St. George's Channel to the Papi Islands , thence on the return it included Green Island and the Solomon Sea. Reconnaissance Area D conformed approximately to the line between Madang and the Kapingamaringi Islands and out across the westerm portion of the Bismarck Sea in a north-south direction. Reconnaissance E was a photophic coverage of the ports of Rabaul and Kavieng and a search of the sea areas enroute.

COMWESPAC'S search and receonnaissance operations were superimposed upon on his ofensvie air attack missions in support of the SOPAC force. His air offensive was directed, commencing on D- Day, primarily at interdicting Japanese air operations in the Rabaul

Area, denying refueling of Japanese planes at Buka enroute to Tulagi, and somothering the Janpanese air power based at Lae and Salamsus by periodic attacks in order to prevent it from reinforcing the Japanese air strength at Rabaul.

COMSOWESPAC'S search and reconnaissance were superimposed upon his offensive air attack missions in support of the SOPAC forces. His air offensive was directed. Commencding on D-Day, primarily at interdicting air oipertions in the Rabaul Area, denying refueling Japanese planes at Buka enroute to Tulagai, and smopthering the Japanese air power based at Lae and Salamauam by periodic attacks in order to prevent it from reinforcing the Japanese air strength at Rabaul.

COMSOWESPAC had directed his aircraft to be prepared to strike hostile naval targets discovered in the North Eastern Area.* This directive "to be prepared to strike" (rather than "to strike") naval targets as well as naval targets is of significance in this study, since it so happened later that the Japanese Cruiser Force (which attacked the Allied Forces at Savo Island) passed with impunity southward through the Solomons on August 8th and northward through the Solomons on August 9th, within a 600 mile radius of Port Moresby during twelve hours of daylight on each day.

COMSOWESPAC'S directive is here analysed since he had been directed by the Joint Chiefs ocf Staff to interdict hostile naval targets as well as hostile air operations as a part of his supporting role for Task ONE.

On August 10th, the day after the Battle of Savo Island, the Army Chief of Staff queried COMSOWESPAC as to "the degree of success you are obtaining . . . in locating and attacking Japanese surface craft."** COMSOWESPOAC replied: "Had arranged with Ghormley for missions if called, but have had no requests".*** It is revealed in the light of this statement that the basis for COMSOWESPAC'S directive merely "to be prepared to strike hostile naval targets was the agreement reached between himself and COMSOPACFOR.

The arrangements made between these two commanders were: (a) that Southwest Pacific air units would concentrate primarily upon interdicting Japanese air operations against the Allied forces in the Tulagai area, and (b) that SOWESPAC aircraft would operate against hostile naval targets only if COMSOPACFOR made specific requests for such attacks direct to COMSOWESPAC Area.****

* COMSOWESPAC Operation Instructions No. 14, July 26th, 1942, and

Annexure (A) to Allied Air Forces Operation Instruction No. 18, July 31st 1942.

** Radio No. 658, CM-OUT 2795, C of St. to CINC, SWPA, August 9th 1942 (August 9th 1942 (August 10th (..) 11 Zone Time).

*** Radio No. C-246, CM-IN 3795 CINC, SWPA to C of St., August 11th, 1942.

**** COMSOWESPAC Dispatch 191034, July 1842, addressed to COMSOPACFOR.

--29--

The reasons why COMSOPACFOR, the designated commander whom the Joint Chiefs of Staff had charged with the responsibility for the execution of Task ONE, would enter into such an agreement are nowhere set down. It is known however, that he was convinced that COMSOWESPAC did not have adequate air strength, for he stated to COMINCH: "I consider means now prospectively available SOPAC sufficient for accomplishment Task ONE provided SOWESPAC Area be furnished sufficient means for interdiction hostile aircraft activities based on New Britain-New Guinea-Northern Solomons Area." In the same message he quoted a previous dispatch to the effect that: "The air forces in sight for the Southwest Pacific Area are not adequate to interdict hostile air or naval operations against the Tulagai area."*

However, despite this inadequacy, the above agreement is not believed to have been sound in all particulars. COMSOPACFOR was in the position of having to rely upon the cooperation and support of SOWESPAC air units to locate and interdict Japanese surface forces in the approaches to Tulagi from Rabaul, since this area lay almost wholly within the SOWESPAC Area. Should not SOWESPAC aircraft have attacked automatically a strong surface ship formation, such as the Japanese Cruiser Force, heading in the direction of Tulagi? The Allied Air Forces North Eastern Area, significantly enough, had launched promptly and automatically a flight of B-17's from Port Moresby on August 2nd to attack an aircraft carrier falsely reported to be in Rabaul Harbor.** Is it not logical therefore to consider that COMSOPACFOR should have insisted that COMSOWESPAC direct his air forces to interdict large and powerful naval forces located in his area which were obviously making advances southward through the Solomons?

It is clearly evident that the planning and the operation of the Allied forces were concerned chiefly with the enemy capability of attacking by air, either from land bases, sea plane tenders, or from aircraft carriers. COMSOPACFOR had expressed this concern to COMINCH when he stated: "I wish to emphasize that the basic problem of this operation is the protection of surface ships against land-based aircraft".* Had COMSOPACFOR considered more fully the enemy capability of attacking with surface ships which could approach through the SOWESPAC Area under low visibility conditions, he might have exercised his own responsibility, rather than to have depended upon the cooperation of SOWESPAC forces, and taken measures to insure that the threat of an enemy surface ship attack was met before it reached Savo Island. Perhaps then he would have been alerted to the need for late afternoon searches in addition to the early morning searches in Sectors II and IV.

*COMSOPAC Dispatch 112000, July 1942, to COMINCH.

**Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific, Operations Report for August 2nd, 1942.

--30--

Perhaps also he would have provided for the air coverage of the approaches from Rabaul and thus have precluded the necessity for CTF 62 later to request a special search of this area.*

(e) Communication Arrangements Between COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC

(Plate III)

The Communication Plan 1-42 (Annex "D" to CTF 63's Operation Plan 1-42) provided, among other circuits, a communications Net "E" established between those air bases from which both long range air searches and heavy bomber strikes could originate. This included Espiritu Santo, Efate, and Noumea in SOPAC and Townsville and Port Moresby in the North Eastern Area of SOWESPAC. This circuit was a rapid and positive means for the wide dissemination of operational information and intelligence, and was in effect an Air Operational Intelligence Circuit (AOIC) as now employed in the naval communication service.

This Communication Plan Provided an additional radio circuit known as Net "C" between the air bases ashore, the tenders, the task group commanders and all reconnaissance and bombardment aircraft in the SOPAC Area. It did not provide an arrangement whereby SOPAC air bases, or task group or force commanders would receive messages or contact reports from SOWESPAC aircraft in flight. This circuit was in effect a task force common, although it was not so designated.

COMSOWESPAC Area's air communication plan was promulgated by the Allied Air Forces in Signal Instructions, Annexure "B" to Operation Instruction No. 18. These instructions provided for the establishment of special point-to-point watches at Port Moresby and Townsville to listen on the AIRSOPAC (TF 63) Net "E". These instructions further provided in paragraph 3 (c):

"All signals originated in North Eastern Area and addressed to South Pacific Forces are to be routed via Headquarters Allied Air Force (Brisbane). Additionally, when urgency demands, they may be routed via Port Moresby or Townsville on the above point-to-point series."

Net "C" also was guarded by the three Allied Air Force base stations in the North eastern Area -- Fall River, Port Moresby and Townsville - for the purpose of being able to communicate with aircraft (in flight) of the South Pacific Force, should such aircraft desire to communicate. Listening watches were maintained and transmitters were ready to reply, but no provision was made for the initiation over Net "C" of messages from SOWESPAC bases to SOPAC bases

*CTF 62 Dispatch 070642, August 1942, addressed to CTF 63

--31--

The procedure governing SOWESPAC Air Force reconnaissance missions was set forth in the Signal Annex to Operations Instruction No. 2, dated May 23, 1942. Contacts made at sea were to be reported immediately by transmission at the target. The reconnaissance plane making contact was to remain in the vicinity of the sighted target until recalled or forced to retire, sending MO's and the plane's identifying call. The Air Force ground station to which the contact was transmitted was to repeat the entire message in acknowledgement.

The contact codes and ciphers to be used by reconnaissance and bombardment aircraft of the South Pacific Area were issued to the Air Command Headquarters, Townsville and to the Naval Officer-in-charge, Port Moresby. Arrangements were made with the latter that North Eastern Area air units have access to the codes.

A study of the above communication plans for the air forces in both the SOPAC and SOWESPAC Areas reveals that adequate means were provided for the prompt transmittal of any contact report to the commands concerned so that immediate and positive action might be taken. CTF 63 made arrangements with COMSOWESPAC that all search reports would be immediately rebroadcast on the respective circuits of the air command in each area.* However, the employment of the means in SOWESPAC in practice, did not exploit the full capabilities of rapid and effective communications, thus causing long delays in the transmittal of vital information. It will be shown later that contact reports in the SOWESPAC Area followed the echelon of command before being broadcast to SOPAC forces.

Fleet broadcast schedules were the primary means of delivering contacts made in SOWESPAC Area to naval units in the SOPAC Area. The two primary fleet broadcast schedules that were available to deliver vital information to forces in the area of operations were the Canberra (VHC) "BELLS" broadcast, which was copied by the SOWESPAC naval units that were involved in the operation (old Task Force 44), and the Pearl Harbor (NPM) "HOW" Fox broadcast, which was copied by the SOPAC naval units.

(f) Allied Deployment of Naval Forces

(1) Approach to Guadalcanal-Tulagi Area.

A large concentration of naval forces was first assembled under the command of COMSOPACFOR in the Fiji Islands in late July 1942. CINCPAC had made available for the execution of Task ONE three Striking Forces of the Pacific Fleet: (1) Task Force 11, flagship Saratoga; (2) Task Force 16,

*Letter to President, Naval War College, from Rear Admiral M.B. Gardiner, USN (Chief of Staff to COMAIRSOPAC, CTF 63, in August 1942), October 20th, 1948.

--32--

Flagship Enterprise; and (3) Task Force 18, Flagship Wasp. COMSOWESPAC had transferred the cruisers and destroyers of Task Force 44 to COMSOPACFOR. These joined at Koro Island, Fiji's with South Pacific Area Amphibious Force (Task Force 62) in which the First Marine Division was embarked, to form the Expeditionary Force, TF 61.

After conducting rehearsals at Koro Island from July 28th to July 31st, the Expeditionary Force (TF 61) sortied on July 31st for Tulagai. CTF 61 headed to the westward for Longitude 159°-00'(E) Latitude 16°-30'(S), passing south of Efate through the New Hebrides en route. At 1200, August 5th, he headed his Expeditionary Force northward along the meridian of 1590 East Longitude and remained in cruising disposition until 1600, August 6th. This track is shown on Diagram "B".

The Allied approach commenced at this latter time. CTG 61.2 (CTF 62) placed in effect his Operation Plan A3-42 and directed the Amphibious Force (TG 61.2) to take the Attack Force Approach Disposition AR-3 and to proceed to the assigned transport areas (Area XRAY at Lunga Roads and Area YOKE at Tulagai), complying with the courses and times specified in Attack Force Approach Plan AR-11. According to this plan, the Amphibious Force continued north to reach position Latitude 09°-50'(S), Longitude 159°-00' (E) at 2235, August 6th, at which time course was to be changed at 040°(T) to close Savo Island at a speed of twelve knots. In the execution of this plan, this change actually was made at 2250.

The Air Support Force, TG 61.1 broke off from its cruising position (relative to TG 61.2) at 1830 by changing course to 305°(T) and increasing speed to twenty-two knots to pass through Point ABLE and Point BAKER (shown on Diagram B) seventy-five miles to the west of the meridian 159° East Longitude. Point BAKER was to be reached by 0030, August 7th at which time TG 61.1 was to change course to 090°(T) to reach Point VICTOR at dawn, the dawn aircraft launching position.

At 0300, the Amphibious Force (TG 61.2), in a position fifteen miles southwest of Savo Island, deployed into two groups: Group XRAY which proceeded to Lunga Roads off Guadalcanal, and Group YOKE which proceeded to Tulagai. Both groups were in Iron Bottom Sound at dawn and arrived at their objectives shortly after sunrise, August 7th.

This deployment at dawn--with the Amphibious force (TG 61.2) in Iron Bottom Sound and the Air Support Force (TG 61.1) operating in its support in the area south of Guadalcanal Island -- established the strategic disposition of Allied forces with which this study of the Battle of Savo Island is concerned, for it was this disposition that the Japanese Cruiser Force had to meet on the 8th and 9th of August. In conjunction with this disposition of surface ships of TF 61, COMSOPACFOR had the land and tender - based aircraft of Task Force 63 deployed and COMSOWESPAC had his land-based air disposed, in the manner already described. In addition, COMSOWESPAC had deployed two submarines in the Bismarck Area for

--33--

reconnaissance and attack patrols.

(2) CTG 61.1 Operates His Carriers

CTG 61.1 operated each of his three carrier striking forces as a separate group, rather than a single task force of three carriers as was done in later operations. He formed them into a disposition approximating an equilateral triangle with the Saratoga in TG 61.1.1 (TF11) at the apex as guide, followed five miles on his starboard quarter by TF 61.1.2 (TF16), and five miles on his port quarter by TF 61.1.3 (TF18).* In this manner these groups remained within mutual supporting distance and visual signal distance of one another.

CTG 61.1's reasons for not combining his task groups into one Task Force of three carriers were:

(a) His belief that protection of a carrier task force under air attack could best be accomplished by the separation of the carriers into groups containing only one carrier each, as was done at the Battle of Midway. At this early date, maneuverability was given almost almost equal importance with anti-aircraft fire in defense of a task force. It was felt that separation would reduce the risk of collision which would otherwise exist in a tight formation when the carriers were taking independent evasion action. In August 1942, the lesson derived from both the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway--namely, that an independent single-carrier task force could be readily penetrated by Japanese attacking planes--had not been adequately evaluated. In later actions, as the volume of anti-aircraft fire of a task force increased in proportion to the increased number of anti-aircraft guns and improved fire control, the importance of maneuverability decreased and the necessity for independent freedom of action for each carrier obtained to a far less degree.

(b) The necessity for obtaining air space for rendezvous and break-up of carrier air groups. At this time the realization had not yet evolved that fighter defense is made easier and more economical by concentrating ships and by controlling a spot defense rather than a dispersal of fighter strength in defense of separated targets.

While TG 61.2 was heading for its anchorage off Tulagai and Guadalcanal, TG 61.1 was operating about seventy miles to the southwest of Tulagai and was generally steaming on a southwesterly course at thirty knots while launching aircraft, since the wind was from that direction and was very light. This task group, commencing at 0530, had been providing air cover for TG 61.2 and air strikes for assaulting enemy positions

*War Diary Enterprise August 1942.

--34--

at Guadalcanal and Tulagai. At about 0625 sixteen fighters (launched by the Wasp) destroyed all of the Japanese aircraft based at Tulagai -- seven Type-9 flying boats and nine seaplane fighters -- without suffering any losses whatsoever.

(3) Approach of TG 61.2 (Amphibious Force)

The approach of TG 61.2 was blanketed by very favorable weather conditions, in that there were clouds and sufficient light rain to cloak the advance of the force. At the same time there was sufficient moonlight to facilitate taking bearings and making the necessary and prescribed changes of courses.* At 0406, Amphibious Group XRAY changed course to 120°(T) to proceed south of Savo Island directly to Lunga Roads. At 0500, Amphibious Group YOKE, in position four miles north of Savo Island, changed course to 120°(T) to make the final approach to Tulagi. At 0614, Fire Support Group MIKE commenced shelling designated targets at Tulagi and at 0617 Fire Support Group LOVE opened fire on Japanese positions at Guadalcanal. Group YOKE arrived at the transport area off Tulagi at 0637 and Group XRAY arrived off Guadalcanal Beach at 0650. As a consequence of these weather conditions, and of the failure of the Japanese to locate TF 61 on August 6th, the advances of the Amphibious Groups on Tulagai and Guadalcanal were effected with complete surprise, and were first reported by the Japanese at Tulagi at 0645. This message was received by Commander Outer South Seas Force at 0652, which time has been accepted in this analysis as the initial contact between Allied and Japanese forces. At this time CTG 61.2 set the hour for landing on Guadalcanal as 0910, August 7th.*

(4) Deployment of SOWESPAC Submarines.

COMSOWESPAC deployed two submarines in the New Britain, New Ireland area during this operation. These were the S-38 and the S-44 which operated independently .

(a) Deployment of S-44.

The S-44 departed Brisbane at 0930, July 24th and headed for a patrol station off Bougainville Island on the assumed Japanese traffic route between Rabaul and Tulagi where she arrived at 0830, July 30th. Sea conditions were poor so the Commanding Officer headed for a patrol station off Cape St. George. He arrived on station at about 0350, August 1st where he noted some merchant shipping. He remained off Cape St. George until morning when he headed up the east coast of New Ireland arriving off North Cape at about 0800, August 4th. Here he encountered considerable merchant shipping, but was unable to close it. At 1845,

*War Diary CTF 62, August 1942, page 5.

--35--

August 6th he headed around the west end of Hanover Island and commenced cruising eastward along the south shore to the entrances of Steffen and Byron Straits where he arrived at about 0700, August 7th*

(b) Deployment of S-38

The S-38 departed Brisbane, Australia at 0930, July 28th and headed for her patrol station off the entrance to Wide Bay, New Britain where she was directed to cover the assumed Japanese traffic lane between Rabaul and Gona, New Guinea. She arrived on station at 1817, August 4th, and at 0300, August penetrated Wide Bay, but discovered no evidence of Japanese activity. The Commanding Officer then headed for a patrol station off Cape St. George, the southern tip of New Ireland, where he arrived at 0610, August 6th and commenced patrolling again.**

The decisions of the Commanding officers of the S-38 and S-44 to change these patrol stations on their own initiative indicated a correct appreciation of their objective which was the destruction of Japanese shipping and their positions at 0652, August 7th, were just short of being very fruitful against the Japanese Cruiser force enroute to Tulagi which passed out the south entrance of Steffen Strait at 0650, August 7th and later passed very close aboard the S-38at 1945, August 7th.

(5) Deployment of Allied Forces at 0652, August 7th.

At 0652, August 7th -- the time at which Commander Outer South Seas Force received the initial contact report from Tulagi -- the various Allied forces deployed in his area were located in the following positions:

(a) TG 61.1 Air Support Force

This force was located sixty-eight miles on bearing 240°(T) from Tulagi, heading southeast.

(b) TG 61.2 (TF 62) Amphibious force

(1) Amphibious Group YOKE was in the vicinity of Tulagi.

Fire Support Group MIKE had commenced shelling the Japanese positions

at Tulagi at 0614, and Transport Squadron YOKE had anchored at 0637.

The screening group at Tulagi remained underway, the Chicago and Canberra

operating with the Bagley and the Henley, Helm, and Blue

providing an anti-submarine screen for the transports.

(2) Amphibious Group XRAY was in the vicinity of Guadalcanal Beach.

Fire support Group LOVE had opened fire at 0617, and Transport

*Third War Patrol Report, S-44, July 24th, 19421 to August 23, 1942.

**Seventh War Patrol Report S-38, July 28th, 1942 to August 22nd, 1942.

--36--

Squadron XRAY had anchored at 0650. the underway anti-submarine screen for the transports consisted of the Selfridge, Jarvis, Mugford and Ralph Talbot. The Australia and Hobart, screened by the Patterson, remained underway.

(c) Submarines

(1) The S-38 was patrolling an eighteen mile line parallel to SW Coast of New Ireland in the vicinity of Cape St. George and eight miles off shore.

(2) The S-44 was cruising submerged about three miles south off the coast of New Hanover en route to Steffen Strait.

(g) Composition of Forces and Tasks Assigned

(1) Composition of Forces

The Expeditionary force, TF 61, was a very powerful force consisting of two almost entirely separate forces; one, the Air Support Force, and the other an Amphibious force. The composition of these forces are set forth below.

(a) TG 61.1 -- Air Support Force

(1) TG 61.1. (Pacific Fleet Task Force 11)

Saratoga (36 VF, 36 VB, 18 VT) 1 CV

Minneapolis, New Orleans 2 CA

Phelps, Farragut, Worden, Mcdonough, Dale 5 DD

(2) TG 61.1.2 (Pacific Fleet Task Force 16)

Enterprise (38 VF, 36 VD, 10 VT) 1 CV

North Carolina 1 BB

Portland 1 CA

Atlanta 1 CL (AA)

Balch, Maury, Gwin, Benham, Grayson 5 DD

(3) T.G. 61.1.3 (Pacific fleet Task Force 18)

Wasp (27 VF, 28 VB, 6 VT 1 CV

San Francisco, Salt Lake City 2 CA

Lang, Sterrett, Aaron Ward, Stack, Laffey, Farenholt 6 DD

(b) TG 61.2, Amphibious Force (TF 62 plus SW Pac TF 44)

(1) TG 62.1, Transport Group XRAY

Fuller, American Legion, Bellatrix, McCawley (F)

--37--

(2) TG 62.2, Transport Group YOKE

Neville, Zeilin, Heywood, President Jackson 4 AP

Colhoun Gregory, Little, McKean 4 APD

(3) TG 62.3 Fire Support Group LOVE

Quincy, Vincennes, Astoria, Hull, Dewey, Ellet, Wilson 4 DD

(4) TG S62.4 Fire Support Group MIKE

San Juan 1 CL (AA)

Monssen, Buchanan 2 DD

(5) TG 62.5, Minesweeper Group

Hopkins, Thever, Zane Southard, Hovey 5 DMC

(6) TG 62.6 Screening Group

HMAS Australia, HMAS Canberra, USS Chicago 3 CA

HMAS Hobart 1 CL

DESRON FOUR

Selfridge, Patterson, Bagley, Blue, Ralph

Talbot, Henley, Helm, Jarvis, Mugford 9 DD

(7) TG 62.7 Air Support Control Group

Fighter Director Group in Chicago

Air Support Director Group in McCawley

Air Support Director Group (Standby) in Neville

(8) TG 62.8 Landing Force (1st Marine Division)

Guadalcanal Landing Group

Tulagi Landing Group

(2) Tasks Assigned

The tasks assigned the Allied naval forces were, in part:

(a) TF 61, Allied Expeditionary Force.

(1) On DOG Day to capture and occupy Tulagi and adjacent positions, including an adjoining portion of Guadalcanal suitable for the construction of landing fields.

(2) To defend seized areas until relieved by forces to be designated later.

(3) To call on TF 63 for special aircraqft missions.*

*COMSOPAC Operation Plan I-42, July 16th, 1942.

--38--

(b) TG 61.1 Air Support Force.

(1) On DOG Day and subsequently, to cooperate with Commander Amphibious force by supplying air support.

(2) To protect own carriers from enemy air attacks.

(3) Top make air searches as seem advisable or as ordered.*

(c) TG 61.2 (TF 62 plus TF 44) Amphibious Force

(1)To proceed to Tulagi in tactical support of Amphibious Force. On DOG Day to seize and

occupy Tulagi and adjacent positions including an adjoining portion of Guadalcanal suitable for the construction of landing fields.

(2) To defend seized areas until relieved by forces to be designated later.

(3) On departure of carriers, to call on TF 63 for special aircraft missions.*

The Amphibious Force was composed of eight separate task groups, but since only the Screening Group and the Fire Support Groups LOVE and MIKE were involved in the Battle of Savo Island , the tasks assigned to these three groups only are pertinent. These tasks were, in part:

(a) Screening Group -- TG 62.6**

(1) To screen the transport groups against enemy surface, air, and submarine attack.

(b) Fire Support Group LOVE -- TG 62.3**

(1) In case of air attack to defend transports and troops at Guadalcanal with anti-aircraft fire, acting under the directions of CTG 62.6.

(2) To support TG 62.6 in case of surface attack.

(c) Fire Support Group MIKE -- TG 62.4.

Same as for Fire support Group LOVE, except that it operated in the Tulagi Area rather than at Guadalcanal.

*CTF 61 Operation Order I-42, July 28th, 1942.

** CTF 62 Operation Plan A3-42, July 1942.

--39--

The composition of TG 61.1, as shown above, combined extreme mobility and offensive striking power. This Air Support Force was replied upon to meet any air or surface threat that the Japanese might be able to bring against the Amphibious Force, in addition to its role of air strikes in support of the landing operations. Allied intelligence did not indicate that there were any powerful Japanese carrier striking force in the vicinity of Tulagai; but the responsible commanders realized that, despite the Japanese carrier losses at Midway, strong Japanese forces might well be brought to bear in or near the Tulagai area. Serious opposition could be expected , not only from land-based aircraft at present within the Bismarck-New Guinea-Solomons area but also from reinforcement aircraft which could be rapidly flown in from the Truk-Ponape area. A combination of attacks from both land-based and carrier-based aircraft was considered to be sufficient to counter such opposition. In addition Allied intelligence disclosed the relatively limited extent of Japanese surface strength within the area. Consequently Japanese surface forces so far reported were scarcely a match for the Allied surface ships within the TG 61.1.

TG 61.2 was, as the above listed composition shows, an extremely powerful amphibious force which possessed the capability of defeating the strongest surface forces that might be employed by the Japanese at this time. With the support of TG 61.1, it also had the means of defeating any land-based and carrier-based aircraft which might be employed against it. The Battles of the Coral Sea and of Midway had seriously decreased the carrier striking power of the Japanese Combined Fleet, and the limited number of airfields within the Solomon Islands restricted the striking power of the Japanese land-based aircraft.

The Screening Group, plus the Fire Support Groups LOVE and MIKE, had sufficient strength to carry out the tasks assigned to it. Its primary role was to defend the transport groups against enemy surface, air and submarine attack during the amphibious operation. During daylight hours, when covered by the air power of TG 61.1, it was capable of defending itself against any probable attack. During the night, when it was without the support of TG 61.1, its preponderance of power against possible Japanese surface attack was considerably lessened. However, it was capable, provided its strength was properly concentrated, of defeating Japanese surface forces known to be in the area, should such forces attempt to interfere with the landing operations during night or low visibility.

(h) The Allied Plan

This study is concerned merely with those aspects of planning for the execution of Task ONE which culminated in the clash between Japanese and allied surface forces in the night action near Savo Island. Consequently the entire plan for the Allied landings and occupation of positions in the southern Solomons has not been included. The Allied plan for

--40--

offensive action in the South Pacific originated with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and was

officially made known by COMINCH and CINCPAC on July 2nd, 1942. Operations were to commence

on August 1st for the accomplishment of the objective in three stages, with the task for

each stage set forth as follows:

-

Task ONE: Seize and occupy Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi and adjacent positions.

-

Task TWO: Seize and occupy the remainder of the Solomon Islands, Lae, Salamoua,

and the northeast coast of New Guinea.

-

Task THREE: Seize and occupy Rabaul and adjacent positions in the New Guinea-New Ireland Area.*

As a consequence of this directive, COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC held consultations and

recommended that the operation not be initiated until adequate air strength was built up

in SOPAC and SOWESPAC Areas. They stated that, in view of (1) the recently developed

strength of the enemy positions, (2) the shortage of airplanes for the continued maintenance

of strong air support throughout the operation, and (3) the shortage of transports

and the lack of sufficient shipping that would make possible the continued movement

of troops and supplies, the successful accomplishment of the operation was open to

the gravest doubts. They therefore jointly recommended that Task ONE be deferred,

pending further development of forces in the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific Areas.

They offered an alternate plan that the Allies proceed with an infiltration process

through the New Hebrides and Santa Cruz Island groups until such time as bases

could be developed for the support of the three stages of the operation as one

continuous movement.**

The Joint Chiefs of Staff refused to defer the operations already underway for Task ONE

for two reasons: (a) that it was necessary to stop without delay the enemy's southward

advance that would be effected by his firm establishment at Tulagi, and (b) that enemy

airfields established at Guadalcanal would seriously hamper, if not prevent,

Allied establishment of bases both at Santa Cruz and Espiritu Santo.

They agreed to provide additional ship borne aircraft and additional surface forces:

to increase the rate of flow of replacement aircraft and to make available for the

South Pacific Area one heavy bombardment group of thirty-five planes.***

COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC then went ahead with the planned operation. COMSOPAC planned

to accomplish Task ONE by seizing the Tulagi-Guadalcanal

*Joint Directive U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, War Diary, COMSOPAC for July 1942-COMINCH

to CINCPAC 022100, July 1942.

**COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC to Joint Chiefs of Staff (COMINCH) Dispatch

081012 July 1942.

***COMINCH to COMSOPAC Dispatch 102100, July 1942.

--41--

area on DOG Day and, after it had been secured by seizing Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands.

The purpose of these operations was to deny these positions to enemy forces and to

prepare bases for Allied future offensive operations.*

The plan was simple and direct. An amphibious force of suitable strength was to seize

the Tulagi and Guadalcanal area under the air support of land-based aircraft flying from

land and seaplane bases within both the SOPAC and SOWESPAC Areas and from carrier-based

aircraft within the Expeditionary Force. It was also to be supported against naval attack

(both surface ships and submarine) by the cruiser and destroyer escorts and screening

ships attached to the amphibious force.

Based on the intelligence available concerning the enemy forces within the objective area

and those capable of being moved into the area in time to interfere with the landings,

the plan was sound. This was particularly true, providing the factor of surprise could be

achieved at the objective area. However, the Allied Commander did not expect to achieve surprise,**

and relied on the coverage of his land and carrier-based aircraft and on the gunpower of

his ships to defeat expected enemy counter-attacks.

(1) General Summary

The preceding discussion of the background for the Battle of Savo Island shows,

in a general way, that:

(a)The Japanese effort south of the Equator was designed to expand Japanese power

in the South Seas Area and to counter any Allied attack that might be made in that area.

This effort was spearheaded by that portion of the land-based air power of the Base Air

Force (ELEVENTH Air Fleet) which was based at Rabaul. It was supported by limited naval

forces based primarily at Rabaul and Kavieng, and by submarines, all under the command

of Commander Outer South Seas Force (Commander EIGHTH Fleet) whose headquarters were at Rabaul.

It was supported also by reconnaissance seaplanes of the Base Air Force based at Rabaul and Tulagai.

(b)The Allied effort in the South Pacific was designed to stop the advance of the Japanese

in that area and to seize advanced bases in the Solomons from which to continue further

operations against the Japanese. This effort was spearheaded by an Expeditionary Force,

strong in naval and air power. It was supported by land-based air power operating both

from SOPAC and SOWESPAC bases. In strategic command of all forces within the SOPAC Area,

including the Expeditionary Force, was COMSOPACFOR with operational headquarters at Noumea.

*COMSOPAC OpPlan 1-42 Serial 0017 of July 16th, 1942.

**COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC to Joint Chiefs of Staff (COMINCH) Dispatch 081017, July 1942.

--42--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (2) *

Next Chapter (4)