|

t

has long been thought, by the present authors among others, that

Blake painted his plates using the standard à la poupée technique,

adapted for his purposes. Compared to any alternatives, the method

is direct, cost effective, and united with the art of painting (Essick,

Printmaker 125-35; Friedman 16; Viscomi, Idea 119-28).

Phillips does not believe this, but, citing Le Blon and Jackson

as precedents, argues that Blake adapted the more complicated manner

of printing and registering multiple plates by printing his own

plates twice, once for the text in ink and again for the illustration

in colors (95). It may seem that questions about printing technique

in general and color printing in particular are of no real importance,

but, as we argue below, using one or the other method significantly

affects our ideas about Blake’s works and their conceptual implications.

Phillips recognizes what is at stake, for he claims that by not

recognizing the two-pull method we are grossly underestimating the

“time and skill” Blake invested in color printing and misunderstanding

his “intentions as a graphic artist” and his intended audience (95).

On these issues Phillips says little beyond some general observations

on Blake’s intended audience in his “Conclusion” (111-13). Nor does

he develop further the effect of his theory on our understanding

of Blake as artist, printmaker, theorist or poet. Surprisingly,

Phillips does not argue (let alone prove) that Blake’s visual effects

in color printing were not possible with single-pull printing.

In short, he does not directly consider (much less answer) the crucial

question: Why divide the printing process into text (first pull)

and illustration (second pull) to reunite them on paper if it was

technically and aesthetically unnecessary to do so? t

has long been thought, by the present authors among others, that

Blake painted his plates using the standard à la poupée technique,

adapted for his purposes. Compared to any alternatives, the method

is direct, cost effective, and united with the art of painting (Essick,

Printmaker 125-35; Friedman 16; Viscomi, Idea 119-28).

Phillips does not believe this, but, citing Le Blon and Jackson

as precedents, argues that Blake adapted the more complicated manner

of printing and registering multiple plates by printing his own

plates twice, once for the text in ink and again for the illustration

in colors (95). It may seem that questions about printing technique

in general and color printing in particular are of no real importance,

but, as we argue below, using one or the other method significantly

affects our ideas about Blake’s works and their conceptual implications.

Phillips recognizes what is at stake, for he claims that by not

recognizing the two-pull method we are grossly underestimating the

“time and skill” Blake invested in color printing and misunderstanding

his “intentions as a graphic artist” and his intended audience (95).

On these issues Phillips says little beyond some general observations

on Blake’s intended audience in his “Conclusion” (111-13). Nor does

he develop further the effect of his theory on our understanding

of Blake as artist, printmaker, theorist or poet. Surprisingly,

Phillips does not argue (let alone prove) that Blake’s visual effects

in color printing were not possible with single-pull printing.

In short, he does not directly consider (much less answer) the crucial

question: Why divide the printing process into text (first pull)

and illustration (second pull) to reunite them on paper if it was

technically and aesthetically unnecessary to do so?

According to Phillips, Blake produced his color prints by inking

the plate’s text areas, registering the paper to plate, printing

and removing the paper, wiping the ink off the plate, adding colors,

registering the paper exactly to the colored plate, printing and

removing the twice-printed paper from the bed of the rolling press,

and (presumably after drying) finishing it in water colors (95,

101, 107). To produce another print from the same copperplate, Blake would

then begin the process anew by wiping the plate of its colors, inking

thetext areas, registering, printing, wiping the ink, adding colors,

registering, and finally printing. Phillips claims that a significant

part of his evidencefor this labor-intensive method in which text

is printed first and illustration second lies in the “Nurses Song”

from Songs of Experience in Songs of Innocence and of

Experience copy E (illus. 8). One can plainly see that this

impression was indeed printed twice, as Essick and Viscomi separately

recognized, but which they, according to Phillips, incorrectly identified

as an individual aberration rather than as one of the most significant

clues in revealing Blake’s color printing practice (Essick, Printmaker

127; Phillips 103; Viscomi, Idea 119). Phillips implies that

this “Nurses Song” deviates from other color prints only in that,

unlike them, it is misregistered, whereas all the other extant color

prints were perfectly registered.

would

then begin the process anew by wiping the plate of its colors, inking

thetext areas, registering, printing, wiping the ink, adding colors,

registering, and finally printing. Phillips claims that a significant

part of his evidencefor this labor-intensive method in which text

is printed first and illustration second lies in the “Nurses Song”

from Songs of Experience in Songs of Innocence and of

Experience copy E (illus. 8). One can plainly see that this

impression was indeed printed twice, as Essick and Viscomi separately

recognized, but which they, according to Phillips, incorrectly identified

as an individual aberration rather than as one of the most significant

clues in revealing Blake’s color printing practice (Essick, Printmaker

127; Phillips 103; Viscomi, Idea 119). Phillips implies that

this “Nurses Song” deviates from other color prints only in that,

unlike them, it is misregistered, whereas all the other extant color

prints were perfectly registered.

Phillips cites Le Blon as an example of multiple-plate printing

to make the point that registering a plate onto a prior impression

was possible (95-96). He states that for the three primary colors

to be recombined into the original colors meant that “the precision

of the registration had to be absolute” (96). From this statement,

one might infer that Le Blon’s color prints show no signs of the

second or third plate—that is, reveal no signs of their mode of

production—but that one plate was registered on top of an impression

from the other so precisely that all telltale tracks were covered.

That, however, never happens.

Color prints produced with two or more plates or blocks—despite

the plates being exactly the same size—always show signs of their

production, usually to the naked eye but always under magnification

or computer enhancement. We have yet to find a multi-plate (and

hence multi-printed) color print that does not show evidence of

at least slight misregistration at some point along its margins,

usually at or near the corners. Such evidence generally appears

in two forms: either as multiple platemarks and/or as a displacement

of one color just outside another. For example, the top right corner

of Le Blon’s Van Dyck Self Portrait (illus. 9) reveals one

plate extending past the other. This effect is even clearer in the

bottom right corner of Le Blon’s Narcissus (c. 1720s) (illus.

10).

We see the same effect in all twenty of the prints in D’Agoty’s Myologie,

including plate 3 (illus. 11), which were thought by contemporaries

to be superior to Le Blon’s, and in all 53 of his smaller three-color

mezzotints for Observations sur l’histoire naturelle, sur la physique

et sur la peinture (1752-55), such as the Tortuise (illus.

12). Even the excellent two-color stipples of Louis Bonnet, such as

Head of a Young Girl Turned toward the Left (1774) (illus.

13), reveal in their corners two platemarks, one slightly displaced

from the other (illus. 14).

The signs of production are also visible in the very best impressions

of the mixed-method and pure chiaroscuro prints, including Kirkall’s

Holy Family and Jackson’s Descent from the Cross, where

the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese

(1739), demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it

is fairly easy to see the misregistrations. the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese

(1739), demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it

is fairly easy to see the misregistrations.

Such subtle misregistrations are not signs of poor printing. They

are to be expected, as printing manuals today acknowledge, regardless

of the registration mechanism used, because damp printing paper

stretches and shrinks in the course of printing the first and subsequent

plates (Hayter 58, Romano and Ross 121, Dawson 100). Reviewing the

various techniques used in his Atelier 17 for registering and printing

multiple plates, Hayter, one of the greatest technicians of twentieth-century

printmaking, states that “it is worthy of note that none of these

methods is absolutely precise” and “examination of the edges of

colour prints made by this system [i.e., multiple plates] will nearly

always show some errors of registration between the different colours

. . . ” (58). Slight misalignments, however, will not disrupt the

visual logic and impact of the design; our eyes tend to make adjustments

or “read” a slight fuzziness in an image as a pleasingly painterly

style. The visual effect of multiple-plate color prints, in other

words, was not dependent on absolute precision but on colors being

overlaid one on top of the other. But the same eyes cannot be fooled

when focused on the margins. “Absolute” (Phillips 96) accuracy in

registration was impossible. [13]

“Nurses Song” in the Experience section of the combined

Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy E (illus.

8) clearly reveals its double printing. The next place to look

for evidence of Blake printing his plates twice—on the grounds that

modes of production can never completely conceal themselves, at

least not to magnification and computers—is his other color prints,

more than 650 of them. Given how poorly printed “Nurses Song” is,

one would reasonably expect to find other examples of misalignment,

albeit less overt. Yet not one of Blake’s other color prints reveals

any sign of misregistration of the plate onto the impression previously

printed in ink. Any suggestion that none exists because poorly printed

impressions were thrown away ought to give one pause. Such a practice

is refuted by “Nurses Song” and many of the other poorly printed

impressions in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

E and other illuminated books.  It

seems clear that Blake rarely threw away anything he printed that

might be salvageable. He had little concern with the finer points

of It

seems clear that Blake rarely threw away anything he printed that

might be salvageable. He had little concern with the finer points

of  precision

printing. If “Nurses Song” was acceptable (as its inclusion in a

complete copy of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience sold

to his major patron indicates), then any print less obviously misaligned

would be too, including hairline misalignments not easily seen with

the naked eye but visible under magnification. One would expect

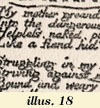

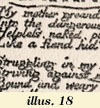

to see quite a few impressions looking like illustrations 18 and

19, where the text and designs, having been printed twice precision

printing. If “Nurses Song” was acceptable (as its inclusion in a

complete copy of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience sold

to his major patron indicates), then any print less obviously misaligned

would be too, including hairline misalignments not easily seen with

the naked eye but visible under magnification. One would expect

to see quite a few impressions looking like illustrations 18 and

19, where the text and designs, having been printed twice ,

are slightly out of register. It takes only a hairline misalignment

of the second plate on top of an impression from the first—or ,

are slightly out of register. It takes only a hairline misalignment

of the second plate on top of an impression from the first—or  on

top of a prior impression from the same plate—to produce this out-of-focus

effect. This is especially true with relief etchings like Blake’s,

because the images are essentially in outline rather than tonal

areas, which makes printing them twice analogous to double printing

the key block in a chiaroscuro woodcut or mixed-method chiaroscuro.

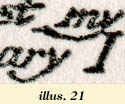

Even impressions that appear dead on, such as illustration 20, reveal,

when magnified, the soft

edges along on

top of a prior impression from the same plate—to produce this out-of-focus

effect. This is especially true with relief etchings like Blake’s,

because the images are essentially in outline rather than tonal

areas, which makes printing them twice analogous to double printing

the key block in a chiaroscuro woodcut or mixed-method chiaroscuro.

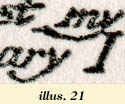

Even impressions that appear dead on, such as illustration 20, reveal,

when magnified, the soft

edges along  the

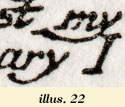

letters that evince a second printing (illus. 21). In impressions

printed once, letters

and other relief lines the

letters that evince a second printing (illus. 21). In impressions

printed once, letters

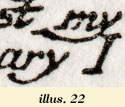

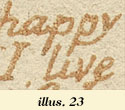

and other relief lines  do

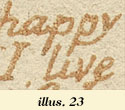

not have any such ghosting (illus. 22), an absence characteristic

of Blake’s color prints, as is demonstrated by details of “The Fly”

and “Holy Thursday” (Experience) from Songs of Innocence

and of Experience copies G and E (illus. 23, 63)

respectively. do

not have any such ghosting (illus. 22), an absence characteristic

of Blake’s color prints, as is demonstrated by details of “The Fly”

and “Holy Thursday” (Experience) from Songs of Innocence

and of Experience copies G and E (illus. 23, 63)

respectively.

Phillips is correct to assume that Blake would have had to wipe

the plate completely clean of ink before adding colors (95, 101),

and then wipe the color off the plate before adding ink to pull

a second impression. This is necessary to help disguise even the

slightest errors in registration, for, as we have seen, if even

minute traces of ink remain on the plate during its second printing

and the registration is anything less than absolutely exact, then

it will produce a slightly fuzzy impression. The same is true for

the colors: if they are left on the plate, then they will be printed

twice in the subsequent impression, once with the ink and once when

colors are replenished. The slightest misregistration will show

up. Masking techniques  like

these, however, work only to a point; the subtlest of misalignment

may fall below the threshold of vision, but it can be detected with

magnification and computer enhancement because relief lines or areas,

even when devoid of ink or colors, still slightly emboss the paper

around their edges. For example, the plate borders in “Nurses Song”

in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy F were wiped

of ink but still embossed the paper (illus. 24). Such embossment

is especially noticeable even without magnification in impressions

color printed from both the relief plateaus and etched valleys of

plates, such like

these, however, work only to a point; the subtlest of misalignment

may fall below the threshold of vision, but it can be detected with

magnification and computer enhancement because relief lines or areas,

even when devoid of ink or colors, still slightly emboss the paper

around their edges. For example, the plate borders in “Nurses Song”

in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy F were wiped

of ink but still embossed the paper (illus. 24). Such embossment

is especially noticeable even without magnification in impressions

color printed from both the relief plateaus and etched valleys of

plates, such  as

those in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies F, G,

H, and T1, The Book of Urizen as

those in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies F, G,

H, and T1, The Book of Urizen

copies

A, C, D, E, F, and J, Visions of the Daughters of Albion

copy F, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell copy F, as is

clearly evident in its plate 21 (illus. 25). If Blake printed his

plates twice with pressure sufficient to print colors from the shallows,

then the second printing, despite its carrying no ink, will reveal

itself as a set of embossed lines around the printed lines (illus.

26). No embossments or haloes of this kind are found in Blake’s

color prints. [14] copies

A, C, D, E, F, and J, Visions of the Daughters of Albion

copy F, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell copy F, as is

clearly evident in its plate 21 (illus. 25). If Blake printed his

plates twice with pressure sufficient to print colors from the shallows,

then the second printing, despite its carrying no ink, will reveal

itself as a set of embossed lines around the printed lines (illus.

26). No embossments or haloes of this kind are found in Blake’s

color prints. [14]

Even wiping the plate of ink and colors between pulls cannot erase

the signs of a second printing. Moreover, wiping oily ink  usually

leaves signs, as is evinced by usually

leaves signs, as is evinced by  the

traces of ink on and along plate borders that Blake wiped of ink

(illus. 27a-27b). There are hundreds of examples of such traces

because Blake wiped the borders of nearly all illuminated prints

produced by 1794 (see, for example, illus.

51, 53).

In addition, wiping ink and colors for every pull is extremely wasteful

in practice. Inking and printing pressure normal for relief can

yield up to five useable prints from one inking in a dark color.

Illustration 28 the

traces of ink on and along plate borders that Blake wiped of ink

(illus. 27a-27b). There are hundreds of examples of such traces

because Blake wiped the borders of nearly all illuminated prints

produced by 1794 (see, for example, illus.

51, 53).

In addition, wiping ink and colors for every pull is extremely wasteful

in practice. Inking and printing pressure normal for relief can

yield up to five useable prints from one inking in a dark color.

Illustration 28 ,

for example, is the third impression printed from one inking of

a facsimile plate. Indeed, in the Tate Britain exhibition, the second

pulls printed from facsimile plates were all more Blake-like than

the first pulls, which were too dark. With lighter inks, like the

yellow ochre used in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

E, one can produce at least two acceptable impressions (illus.

71, 72,

73). The

pigments, oil, and glues used to make inks and colors cost money,

and so do rags used to wipe the plates clean. These unnecessary

expenses and the time required to clean oily ink and glue-based

colors from the copperplates between each impression make this method

of color printing expensive and labor-intensive for no aesthetic

gain, for it creates prints without any visual differences (other

than the telltale signs of double printing) from those produced

with single pulls at far less effort and cost. ,

for example, is the third impression printed from one inking of

a facsimile plate. Indeed, in the Tate Britain exhibition, the second

pulls printed from facsimile plates were all more Blake-like than

the first pulls, which were too dark. With lighter inks, like the

yellow ochre used in Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy

E, one can produce at least two acceptable impressions (illus.

71, 72,

73). The

pigments, oil, and glues used to make inks and colors cost money,

and so do rags used to wipe the plates clean. These unnecessary

expenses and the time required to clean oily ink and glue-based

colors from the copperplates between each impression make this method

of color printing expensive and labor-intensive for no aesthetic

gain, for it creates prints without any visual differences (other

than the telltale signs of double printing) from those produced

with single pulls at far less effort and cost.

But one need not argue the point hypothetically about labor, time,

money, and materials, or even about the astonishing absence of fuzzy

impressions, ghost texts, and embossed haloes unavoidable in two-pull

printing. To this negative evidence that argues against the two-pull

hypothesis we can add a wealth of positive evidence that  Blake

did not wipe his plates of ink or color between pulls but continued

to replenish the ink and colors. Printmakers are led by the physical

properties of their materials to replenish ink instead of wiping

and starting over again Blake

did not wipe his plates of ink or color between pulls but continued

to replenish the ink and colors. Printmakers are led by the physical

properties of their materials to replenish ink instead of wiping

and starting over again  because

ink transfers best once the plate is worked up. The repetition of

inking accidentals and colors in sequentially pulled prints, such

as the two proof impressions of The Book of Urizen plate

25, color printed but not finished in watercolors because

ink transfers best once the plate is worked up. The repetition of

inking accidentals and colors in sequentially pulled prints, such

as the two proof impressions of The Book of Urizen plate

25, color printed but not finished in watercolors  (illus.

29-30), or the finished impressions of plate 24 in copies F and

C (illus. 31-32), demonstrates that Blake printed more than one

impression from an inked plate and added ink and colors to a pre-existing

base.

[15] (illus.

29-30), or the finished impressions of plate 24 in copies F and

C (illus. 31-32), demonstrates that Blake printed more than one

impression from an inked plate and added ink and colors to a pre-existing

base.

[15]  To

assume otherwise is to assume that repetition of colors and their

placement was due to Blake trying to replicate the previous impression—i.e.,

reproducing a model—but, given the differences introduced, doing

a very poor job of it. Clearly, it is more reasonable to conclude

that the repetition of accidentals is due to Blake not wiping

the plate clean between impressions than to conclude that he minutely

copied irrelevant and even visually disruptive droplets and smudges

of ink or color, using the prior impression as his model. The To

assume otherwise is to assume that repetition of colors and their

placement was due to Blake trying to replicate the previous impression—i.e.,

reproducing a model—but, given the differences introduced, doing

a very poor job of it. Clearly, it is more reasonable to conclude

that the repetition of accidentals is due to Blake not wiping

the plate clean between impressions than to conclude that he minutely

copied irrelevant and even visually disruptive droplets and smudges

of ink or color, using the prior impression as his model. The  repetition

of colors, and in some cases their diminishing intensity because

Blake did not add more color for a second impression, lead to the

same conclusion. Even the impression of “Nurses Song”

that was printed twice, the very grounds for the two-pull hypothesis

and for thinking that text and illustration were printed separately,

shows two top plate borders in yellow ochre ink (illus. 33), which

means that ink was printed with the colors and not wiped between

pulls. repetition

of colors, and in some cases their diminishing intensity because

Blake did not add more color for a second impression, lead to the

same conclusion. Even the impression of “Nurses Song”

that was printed twice, the very grounds for the two-pull hypothesis

and for thinking that text and illustration were printed separately,

shows two top plate borders in yellow ochre ink (illus. 33), which

means that ink was printed with the colors and not wiped between

pulls.

While one would expect to see fuzzy impressions and other signs

of misregistration in two-pull printing, what one would not expect

to see are perfectly clean fine white lines bordering the relief

areas of prints color printed from both levels. For example, in

illustrations 25,

29, 30,

31, 32,

the fine white lines between the colors printed from the shallows

and the ink printed from

the relief surfaces are created by printing pressure that was insufficient

to force the  paper

onto the escarpments between the etched valleys and the relief plateaus

of the copperplate. Thus, the paper could not pick up any ink or

color from those bordering escarpments. We see precisely the same

effect in monochrome, ink-only prints, which no one doubts were

printed in one pull, such as Europe copy H plates 1 and 4

(illus. 34a, 35). In these impressions, the inking dabber accidentally

inked paper

onto the escarpments between the etched valleys and the relief plateaus

of the copperplate. Thus, the paper could not pick up any ink or

color from those bordering escarpments. We see precisely the same

effect in monochrome, ink-only prints, which no one doubts were

printed in one pull, such as Europe copy H plates 1 and 4

(illus. 34a, 35). In these impressions, the inking dabber accidentally

inked  the

shallows along with the relief areas, and both were printed simultaneously.

The fine white lines between relief and recessed areas were created

either by the dabber not depositing any ink on the escarpments or

by the paper not creasing at an angle sharp enough to pick up any

ink from those escarpments, in spite of relatively heavy printing

pressure. The effect in plate 1 of Europe copy H (illus.

34a) become clearly evident when compared with an impression of

the same plate which lacks the accidental deposits of ink in the

etched shallows (illus. 34b). the

shallows along with the relief areas, and both were printed simultaneously.

The fine white lines between relief and recessed areas were created

either by the dabber not depositing any ink on the escarpments or

by the paper not creasing at an angle sharp enough to pick up any

ink from those escarpments, in spite of relatively heavy printing

pressure. The effect in plate 1 of Europe copy H (illus.

34a) become clearly evident when compared with an impression of

the same plate which lacks the accidental deposits of ink in the

etched shallows (illus. 34b).

The white line in the branches of plate 1 of The Book of Urizen

copy D is most telling (illus. 36) ;

here we can actually see Blake painting the plate, applying

his green color on the inked relief lines and the green spilling

over and touching the shallows on both sides of the line,

creating white spaces between color and branches. If plates with

colors from the shallows were printed twice, then the white line

would be uniformly intersected with color. These white lines could

not be perfectly aligned, even if registration of the plate was

absolutely perfect, because the dampened paper, as Hayter and others

have pointed out, would have minutely changed its shape while being

passed through the press, even if printed with light pressure. This

makes perfect registration of the white-line escarpments of the

second pull impossible—and detection under magnification or computer

enhancement possible. ;

here we can actually see Blake painting the plate, applying

his green color on the inked relief lines and the green spilling

over and touching the shallows on both sides of the line,

creating white spaces between color and branches. If plates with

colors from the shallows were printed twice, then the white line

would be uniformly intersected with color. These white lines could

not be perfectly aligned, even if registration of the plate was

absolutely perfect, because the dampened paper, as Hayter and others

have pointed out, would have minutely changed its shape while being

passed through the press, even if printed with light pressure. This

makes perfect registration of the white-line escarpments of the

second pull impossible—and detection under magnification or computer

enhancement possible.

Accidental flaws in one-pull printing can be mistaken as evidence of two-pull printing. That such accidentals appear in Blake’s monochrome

impressions, unquestionably printed only

of two-pull printing. That such accidentals appear in Blake’s monochrome

impressions, unquestionably printed only once, should be sufficient warning against misinterpreting their

mode of production. For example, the droplets of color in the margins

of plate 24 in The Book of Urizen copies C and F (illus.

37-38), which may lead one to suspect the edge of a second plate,

is an effect also present in monochrome impressions, such as America

copy H plate 10 and Europe copy H plate 1 (illus. 39-40)

that were assuredly printed just once. One-pull prints can even

exhibit the slight fuzziness, so typical of multi-plate and multi-pull

printing, at the margins between printed and unprinted surfaces

because of slippage between paper and plate when run through the

press. Color printing, particularly when done from the

once, should be sufficient warning against misinterpreting their

mode of production. For example, the droplets of color in the margins

of plate 24 in The Book of Urizen copies C and F (illus.

37-38), which may lead one to suspect the edge of a second plate,

is an effect also present in monochrome impressions, such as America

copy H plate 10 and Europe copy H plate 1 (illus. 39-40)

that were assuredly printed just once. One-pull prints can even

exhibit the slight fuzziness, so typical of multi-plate and multi-pull

printing, at the margins between printed and unprinted surfaces

because of slippage between paper and plate when run through the

press. Color printing, particularly when done from the  shallows

as well shallows

as well  as

the relief areas, multiplies

the chances for accidental deposits of ink and colors that do not

contribute to the printed image, calligraphic or pictorial. Thus

it should be no surprise that Blake’s color prints show, on average,

more accidental effects than monochrome impressions. as

the relief areas, multiplies

the chances for accidental deposits of ink and colors that do not

contribute to the printed image, calligraphic or pictorial. Thus

it should be no surprise that Blake’s color prints show, on average,

more accidental effects than monochrome impressions.

|

the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese

(1739), demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it

is fairly easy to see the misregistrations.

the

tonal blocks extend slightly past the key blocks (illus. 15-16). Even

Jackson’s Venetian series—thought to be “without doubt the high point

of chiaroscuro printing” (Friedman 6)—reveal their mode of production,

as the corner of Holy Family and Four Saints, after Veronese

(1739), demonstrates (illus. 17). In all of these illustrations, it

is fairly easy to see the misregistrations.