A Deep Affinity for Verne

A language teacher in Hong Kong is also a leading authority on the great French author,

as Jonathan Braude discovered

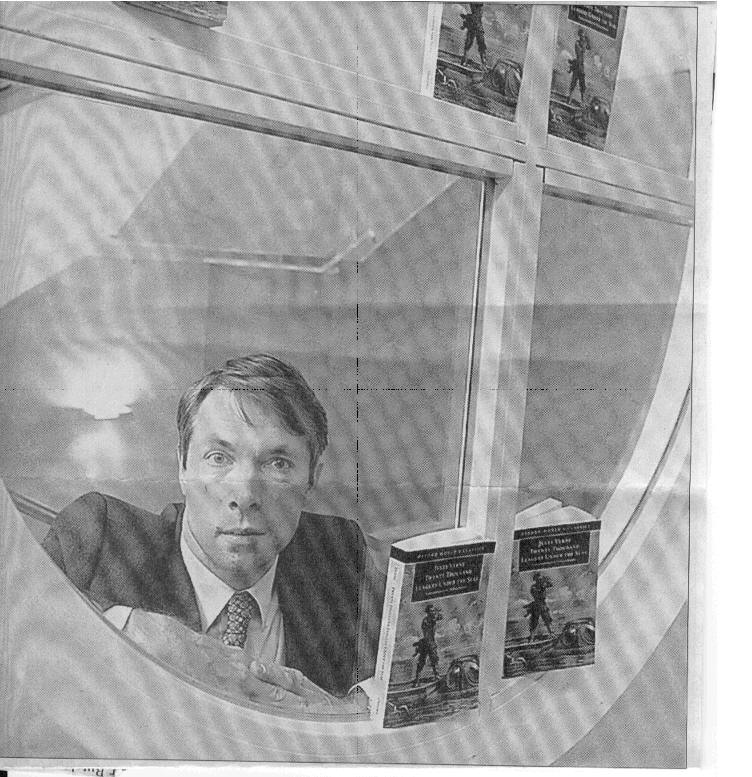

It may seem odd to have a renowned authority on Jules Verne teaching English in Hong Kong. Even odder that he should ring up to say he has just "hijacked" the Oxford University Press Oxford World Classics series, relaunched last month, with his new edition of Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

Face to face, in the unlikely setting of the Hong Kong Institute of Education's Tai Po campus, Dr William Butcher's nervous body language hardly matched his brash telephone manner and the hard-sell. But that seemed just one of his many contradictions.

Dr Butcher's PhD from the University of London established him as one of

Britain's first serious Jules Verne scholars, but has not so far launched

him on a spectacularly successful academic career.

career.

A student of French literature, and a leading specialist on a French author only now beginning to be taken seriously in Britain, he is teaching English at a third-tier Hong Kong institution, where his French courses for beginners are outside the main timetable.

His first degree, from Britain's Warwick University, was in pure mathematics. He has a profound interest in computational linguistics and computer-assisted language learning. But his two-year, part-time lectureship in computational linguistics at Hong Kong University finished last year.

The OUP edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues, just published with Dr Butcher's introduction, appendix and 60 pages of notes, bears his name as not only editor but also translator.

Most publishers regard literary translators as specialist professionals and do not expect editors to produce their own English versions. Dr Butcher ended up translating Verne's masterpiece as a vehicle for his research.

He makes it all sound easy. The first draft was done "on a beach in the Philippines, with the waves lapping in the background" and dictated into a tape-recorder at a rate of 50 to 60 pages a day.

Only then was the translation polished and repolished through 10 to 12 drafts. The idea was not only to make the book readable, while matching the tone to Verne s 19th-century style. It also had to be academically useful.

And in the process he was doing the real work with multi-lingual dictionaries, encyclopedias and specialist works, correcting Verne s mistakes, looking up countless literary, biblical and political allusions and tracking down the exact English names of hundreds of fish and obscure geographical locations. Much of his research involved reading microfilms of Verne's original manuscripts, which often varied considerably from the published version.

"Originally," Dr Butcher said, "I agreed to adapt an existing translation (of Twenty Thousand Leagues). But I realised it would be quicker to do my own."

Since he had already translated Verne's Journey to the Centre of the Earth and Around the World in Eighty Days for the series, OUP was happy enough to commission a full translation, but not ready to pay for one. The firm's payment was based on its original brief to tidy up the obscurities, paraphrase rare words and prepare a critical introduction and limited, basic notes.

But although Dr Butcher was "bitter" at this, preparing his own 1,000-page manuscript also suited his purpose - to prepare a critical edition in his role as an academic.

"The book is not in line with the guidelines of the World's Classics series. There's an expanded critical content. That's the only reason I do it.

"But that's what I mean when I say I hijacked the series."

However, Dr Butcher has also done the reader - and the publisher - a favour. Verne scholarship became fashionable in France years ago, but interest took longer to develop in the English-speaking world. The English world's disdain is based partly on the weakness of many existing translations, which not only cut the French originals by up to 20 per cent, but were peppered with basic mistakes. One glaring example: where the French version talks of blowing up an island, the English usually has "jumping over" an island.

There has also been a perception of Verne as a children's science fiction writer, although the author saw himself as writing for an adult audience. As Dr Butcher points out in his introduction to Twenty Thousand Leagues, Verne not only denied he was the inventor of submarine navigation. but claimed he was never specifically interested in science, "only in using it to create dramatic stories in exotic parts".

"Indeed, his reputation as a founding-father of science fiction has led to a major obfuscation of his literary merits," the book thunders.

The notion of Verne as a romantic figure of high literary worth is something English-speaking readers may take some time to get used to. In fact, Dr Butcher's PhD examiners considered failing him, partly because they did not see Verne as a "real writer" and partly because they did not like Dr Butcher's "new criticism" style.

But as Dr Butcher readily says, the fault is not only with English philistinism but with Verne's original publisher, Hetzel, who did not correct the misconception that Verne's simple language meant the book was for children.

And, since the books were published in the latter half of the 19th century, it comes as no surprise that the powerful sexual imagery - and even some of the brutality - of Verne's manuscripts and letters was bowdlerised from the published edition.

Hetzel also seems to have had some fairly Murdochian views about the relationship between his imprints and international politics. In the manuscripts, Captain Nemo, the enigmatic submariner of Twenty Thousand Leagues, was a Pole, obsessed with revenge for the rape and murder of his wife and daughter at the hands of the Russians. In the published version, his nationality is unknown, the source of his hatred obscure, and his motives for travelling the oceans, sinking an international array of shipping, uncertain.

The changes were made at Hetzel's instigation, because he did not want to offend the Russian ambassador to Paris.

Dr Butcher has confined himself to mentioning the changes in the introduction and notes, partly at OUP's insistence.

As the introduction puts it: "It is not clear what Verne would have done on his own, nor whether Hetzel's interventions were harmful overall. We do not seem entitled, in sum, to argue that the stronger images are invariably what Nemo and the novel are 'really' like."

At 46, Dr Butcher's future direction is still taking shape. Apart from the continuing passion for Verne, and further work on a book on natural language processing, he really wants to teach French. There is a new commitment to the language at the HKIE. So the ambition may not be impossible to fulfil.

But for a man with a deep love and knowledge of the language, it is, he confides, a "shock" teaching French in Hong Kong. Chinese speakers encounter more vocabulary difficulties than English speakers and have little knowledge of the culture.

Jonathan Braude