2019: Volume 11, Issue 1 - Table of Contents

Online Journal Trends:

A partial exploration into several questions such as how to predict a journal’s longevity, whether academic journals are living up to the hype of online publishing, and more

Jonathan Lillie

Loyola University Maryland

NMEDIAC Managing Editor

A few years ago I wrote an introduction to the 2013-14 issue of NMEDIAC that aside from discussing the implications of that issue’s featured essays and new media art also commemorated the journal’s 12th year of existence. When the journal’s other founders and I began talking in 2001 about launching a web-based academic journal the World Wide Web had only been popular as a mainstream communication platform for a few years. In that introduction (Lillie, 2014) I wrote:

We started on this ambitious endeavor in late Spring 2001, inspired by new online-only journals like the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC, founded 1995) and M/C, a Journal of Media and Culture (founded 1998), and other scholarly web projects such as the Center for Cyberculture Studies. Our main goal in founding NMEDIAC (which by the way some pronounce like "immediacy", while others pronounce similar to the word, "maniac" n-meedy-ak), was to use the publishing power of the web to give voice to scholarship from across the disciplines that addresses how people engage new media in their lives.

Sadly, the Center for Cyberculture studies, which published many great academic book reviews stopped publishing many years ago. On the other hand the CMC journal is still going strong. From its beginning it was tied to the International Communication Association, which publishes and provides the journal’s leadership and funding. M/C, changed its name to M/C (Media/Culture), but is also still publishing at a strong pace. M/C is most similar to NMEDIAC in that it was founded by a small group of young scholars independent from any larger organization. However in an attempt to establish more stability, the journal aligned itself in 2004 to the Creative Industries Faculty at Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

NMEDIAC is nearing its 20th birthday, which is a cause for celebration, but unfortunately as managing editor I am worried that this might be the last issue of the journal. It’s not for sure yet, but NMEDIAC might not make it to 20. In the past many scholars were willing to serve as editors and reviewers, but in the last few years it has been difficult to find such volunteers. I surmise that at many mid-sized and small universities service to the discipline (as opposed to service directly to the university) does not hold as much weight as in decades passed. Larger schools are looking for their faculty to contribute to the big name associations that run big name conferences and journals. This is not meant to be a bitter portrayal, but rather a realistic appraisal of the context in which scholars decide how to spend some of their time for the betterment of their disciplines, careers, and intellectual pursuits.

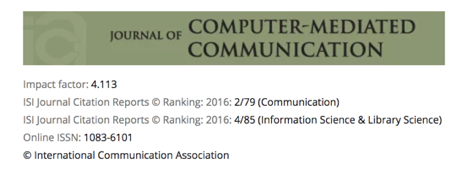

Figure 1. Screen capture taken of CMC website in April of 2019.

Also in recent years the number of article submissions to NMEDIAC has fluctuated greatly. Over the last three years we have had only nine submissions. Only five of those met the standards to be sent for blind peer-review, and three passed through that process to be included in this issue. All three are good scholarly work that should be published for the knowledge and insight they provide, however these scholars and all tied to academic institutions have to closely consider which journals to submit articles to. Of course such decisions could be very strategic and/or personal. In my case, when I apply for promotion to full professor one of the standards will be whether or not I have “quality” publications. In my mind blind peer-review is the ultimate test of quality, and it is the main insurance of quality that NMEDIAC and other journals are able to provide. In a review of studies of journals’ use of double blind review Tvrznikova (2018) observes that, “Current research suggests that double-blind review reduces bias that might arise while assessing quality of the research presented in a manuscript, without imposing any major downsides. Double-blind review offers a solution to many biases stemming from author’s gender, seniority, or location and should be a foundation of any journal that strives to evaluate author’s work strictly based on the quality of the research presented in the manuscript” (p. 3)

Putting articles through a rigorous double blind system is a time-consuming process for all involved, but it seems that some think it is not enough to show quality. Many journals have thrown their lot in to “impact factors” and journal rankings to show their quality. I have firsthand heard people say they will only submit articles to journals with high impact factor scores because they think it will help them out in tenure and promotion decisions. At my institution deans use indices such as the impact factors of journals a professor has recently published in to help decide annual evaluation ranking levels, which directly impact the amounts of annual raises. But I have also heard and read many people ridicule the perceived importance of journal impact factors, such as this critique in Science Magazine, and question how these scores are calculated. Needless to say, some of the most important and insightful articles out there are on websites and books that are not part of the impact factor trend.

The possibility that NMEDIAC might “close its doors” (don’t worry the old issues and articles will be on the Ibiblio servers until the apocalypse) or at least take a siesta for a while has me pondering many questions; and these questions of how journals show their quality, and more importantly how journals survive prompted me to a search recently for what factors may help to predict a journal’s longevity, or the opposite, what factors my predict a journal’s demise.

The creation of “publish or perish”

In the mid-1960s a researcher startled by the rapid growth of new academic journals predicted that 50 years from then there could be close to 1 million journals. Though the number of publications has not bloomed to that lofty prediction, the number of journals today is perhaps probably around 30 thousand. Thus from a certain point of view the proliferation of academic journals is still considerable (see Björk 2012, 2013; Björk et al., 2010; and Jinha, 2010). To be sure the post WWII period saw growth not only in the size and number of higher education institutions (meaning colleges and universities) but also the growth in the number and diversity of academic disciplines. A steady increase of academic journals matched this growth (Lowe, 2012) to address the changing numbers and needs of academics. In particular academic communities were simply becoming too large and diversified. Prior to the 1940s a new professor could be hired based on the peer assessment of colleagues of colleagues and one publication or a performance at a conference or two. Though mentor assessment and recommendation was still vital in the post-world war period, more conferences and journals tied to associations for new and existing disciplines emerged as venues for all the new PhDs seeking tenure-track positions and then tenure itself. Evidence of conference attendance and early-publication also became important for hiring committees that increasingly had to vet tenure-track job applicants whose mentors the committee members did not always know personally or by reputation.

Lowe notes also that the purpose or role of the journal article has also changed. He argues that in education and other areas of the humanities the “learned article” in the first half of the 20th century and before were seminal works that helped young scholars understand a vital thesis or discipline. However, he observes that by the post war period the purpose of the academic journal article had, “become far more varied and in any one edition of a particular journal articles of differing type and provenance may frequently sit alongside each other” (2012, p. 105). Both Lowe, Soames (2003) and Cooper (2013) trace how the increase of PhDs, PhD programs, and tenure-track positions inevitably lead to an increase in sub-fields and specialization in the post-world war decades. Mabe (2003) finds a direct correlation between the number of academic scholars and academic journals, and Mabe and Amin (2001) argue that the annual percent increase in new journals has been steady (around 3.4 percent) since before 1900, and hence the mere number of scholars, not changing demands for tenure-track faculty, is the key factor behind journal growth. Looking at the literature it does seem that both these explanations are more or less correct. Though there does seem to have been larger upticks of new journals appearing in the 1950 and 60s and then again in the early 2000s, as academic web-publishing technology solidified, the general trend for the last 120 or more years has been a steady increase over the years in the overall number of journals.

Looking at the 50s and 60s, even a growing number of general-area journals in a given field could not keep up with scholarly production in that postwar period. New specializations began to sprout their own journals. Soames notes, “Gone are the days of large, central figures, whose work is accessible and relevant to, as well as read by, nearly all,” scholars in a discipline (Soames 2003, 463). Here again the needs of so many new PhDs and Assistant Professors is evident in shaping the ecosystem of academic publishing. Again, Lowe notes that quantity and character of academic publications was not a primary concern for hiring or promotion in the early decades of the 20th century and before, but in the postwar period publication became perhaps the key criteria. This “publish or perish” obsession continues today over half a century later (with the required nod to teaching of course). “Whilst 50 years ago it was not unusual for appointments to be made to university departments on grounds of potential, it has become much more frequent, in recent years, to demand published articles as evidence of suitability for employment,” Lowe writes. “All of these factors have conspired to encourage young researchers to begin publishing much earlier in their careers than was the case, and this has beyond doubt had a major impact on the kinds of article that get into print” (p. 105). Within this development peer-recognition through conferences and dossier reviews became very important. Specialized sub-area journals and conferences (including area groups at larger conferences) helped young academics develop peer-groups to assist in such support and recognition.

Lastly, as Lowe notes in the passage below, this shift toward the publication mania that has become the norm in academia has created a whole new commercial industry that rivals textbooks in scope and importance to higher education today. And though plenty of quality work comes out of commercial presses, their bottom line of course is to make $$$ and encourage scholars to produce and publish as many big words as possible.

“Another development which should not be overlooked in this analysis is the extent to which the control of academic journals, not just in terms of marketing, but also, in respect of content, has shifted from academics towards the professional publishing houses. As the learned societies moved towards closer and tighter contractual relationships with major publishers, with royalties accruing to these societies from sales, marketing became of much greater significance.” - Lowe p. 105

Journal Lifespans

In a recent study Liu et al. (2018) looked at the survival rate and lifespan factors of academic journals, noting that very little research has been done on this topic. They designed a quantitative analysis of journals, focusing on the period from 1965 to 2015 using Ulrich’s database of journals, which has been the primary source for calculating journal numbers and trends for scholars doing research in this area in the last few decades.

The study revealed that most journals are able to survive at least a few years but year 4 of a scholarly journal is an important milestone with many ending publication or becoming inactive in year 3 or 4 (Gu & Blackmore, 2016). Titles that continue to publish by year 4 are much more likely to still be publishing in year 10 and beyond. Several factors that also predict that whether a journal is more likely to cease publication early include those publishing in the area of technology; those published in the China, the UK, Russia, and India; and those published in only one language. Another interesting finding was that titles that offered both print and online formats in the first year of launching are more likely to survive than those initially offing online-only or print-only formats at launch. Using a peer-review system for selecting articles also predicts greatly survivability as does publishing in multiple languages. On the flip side, those publishing in just one of the imperial languages, Manadrin Chinese, English, or Japanese are less likely to survive. NMEDIAC meets some of the criteria predicting longevity (peer-review) but also some predict early demise (online only, one imperial language).

Based on the literature it seems that NMEDIAC is not really elderly, but certainly solidly middle aged as a 20 year old. But that is complicated by the fact that the average age of journal termination is 20. The Liu also observed that since 2000 journals have tended to terminate at a lower rate. They speculate that this could be due to lessons learned by publishers and editors. For example, in hard financial times a journal could switch to online-only publication whereas in a previous era it may have needed to terminate.

In another recent study, D’Souza et al. (2018) surveyed over 5300 scholars about their experiences and opinions as academic journal authors. A majority of those surveyed said manuscript preparation was the most challenging experience for them as authors. Perhaps not surprisingly many wanted improvement in how long it took for articles to go from acceptance to publication and felt that journals could make it easier for authors to communicate with editors. In this area they felt that guidelines for both paper acceptance and article preparation were not clear at many journals. The impact factor of a journal was found to be the most important criteria among authors for why they chose to submit to some journals over others.

A few years ago, Ian Cooper the founder and one of the editors of the wide reaching Blackwell Compass series of philosophy journals wrote of three immerging trends that he predicted would dominate the future of academic journal publishing (Cooper, 2013). The first he calls, “Bells and Whistles,” which describes the wide range of media types available to web-based content delivery systems used by the majority of journals today. Academic articles can now have embedded videos, streaming audio, interactive data graphics, and more, not to mention hyperlinks and photos. Of course many of these options have been around for 10 to 15 years and Cooper argues that both authors and readers are going to want to use them.

The second area is “online collaboration and discussion.” He observes that academics have been using listservs, discussion boards, blogs and like for years and journals should connect article authors and readers to such discussion communities in a similar way that conferences help to create scholarly conversations. And lastly he argues that young academics expect everything (meaning research) to be online. This translates to journals needing to be up to date with SEO and newer forms of indexing and archiving.

Writing now in 2019, it is still very much in the air whether journals are moving to try to achieve the first two aspects of Cooper’s future. A 2012 study of all journal articles indexed by the Scopus database found that from 2006 to 2011 YouTube video citation in scholarly articles increased but was still pretty minuscule overall with video citations most common within arts and humanities (0.3%) and the social sciences (0.2%) (Kousha, Thelwall, Abdoli, 2012). Granted a content analysis of journal articles could tell us much more like how many journals allow images, video, and other media types to be embedded in the online version and how many articles/authors take advantage of that. Such a content analysis could also tell us about how journals use/allow hyperlinks and offer connections to online discussions or even just the author’s email address.

My own anecdotal observation is that many journals are very rigid in publication formats. HTML versions of articles tend to be very similar to PDF versions and both versions are designed to be deliverable through database searches as opposed to mostly found through web searches and essentially existing only on the journal’s home server as we do with NMEDIAC. Since there is only one home for NMEDIAC articles we can embed whatever media the author wants, but this means that databases that can deliver pre-packaged articles on demand won’t/can’t index and deliver our articles.

Conclusion: What are we missing? What don’t we know?

In analyzing here current trends and issues for academic journals it is apparent that there are many things that we (or perhaps just I) don’t know. As a ginormous global institution higher education is obsessed with publication and perhaps not surprisingly the delivery forms for journals tend toward utilitarianism as opposed to author control and creativity. Digital publication forms seem to be focused on retrieval through databases and easy portability which correlates to Coopers last suggestion that scholars want all research to be easily accessible. Unfortunately there are very few studies that analyze whether there really is a dearth of media types used in journal articles, and if this is due to journal guidelines, web CMS inadequacies, or author preferences. On the issue of predicting journal longevity there have been more studies done, but I could not find anything on why specific journals were created or were terminated. In other words there is no qualitative data available. It seems that there are still many answers that need to be found. I am in the beginning steps of setting up a qualitative survey that I plan to email out to journal editors and founders to find some of these answers.

There are also many other areas that could be explored to shed more light on all of these questions. This articles does not get into the whole trend and debate over “open access” online publishing (see Guerrero and Piqueras, 2004) or the infamous pay-to-publish journals. I also did not step into the quagmire that is the critique of the whole orientation of higher education toward “publish or perish” and what type of end results it engenders or how alternatives might serve the disciplines, schools, and the communities around schools better. There are many areas such as pedagogy-focused articles that are frowned upon or not given equal weight. Why should an article that is the end result of community service a professor was involved with be less worthy or important than a traditional research study? In today’s academic world, the former certainly would not stand a chance of acceptance at many peer-reviewed journals with high impact factors. I would like to think that many colleges and universities would see the value in it however and accept its publication at a regional or smaller journal, or a book chapter at a small press, as equal to one of the “top journals.” We have to ask ourselves is the end result supposed to be helping to create a better world or spending more effort on making ourselves look like important people.

References

Björk, B.-C., & Solomon, D. (2012). Open access versus subscription journals: A comparison of scientific impact. BMC Medicine, 10(1), 73.

Björk, B.-C., & Solomon, D. (2013). The publishing delay in scholarly peer-reviewed journals. Journal of Informetrics, 7(4), 914–923.

Björk, B.-C., Welling, P., Laakso, M., Majlender, P., Hedlund, T., & GuÐnason, G. (2010). Open access to the scientific journal literature: Situation 2009. Public Library of Science, 5(6), e11273.

Carpenter, P. (2010). The Future of Publishing. Sociology Editors

Forum. Available at: http://asaeditorsforum.wordpress.com/2010/08/

05/sociology-podcast-1-the-future-of-publishing/

Cooper, L. (2013). Trends in Academic Publishing. METAPHILOSOPHY, 44(3).

Gu, X., and Blackmore, L. K. (2016). Recent trends in academic journal growth. Scientometrics, 108(2), 693–716.

Guerrero, R., & Piqueras, M. (2004). Open access: A turning point in scientific publication. International Microbiology, 7(3), 157–161.

Gunnarsdottir, K. (2005). Scientific journal publications on the role of electronic preprint exchange in the distribution of scientific literature. Social Studies of Science, 35(4), 499-501.

Jinha, A. E. (2010). Article 50 million: An estimate of the number of scholarly articles in existence. Learned Publishing, 23(3), 258–263.

Lillie, J. (2014). Twelve years of NMEDIAC: An introduction to the Winter 2013-14 issue. NMEDIAC, The Journal of New Media & Culture, 12(1). Available at: http://www.ibiblio.org/nmediac/winter2014/Articles/Issue_Introduction_JonathanLillie.html

Liu, M., Hu, X., Wang, Y., and Shi, D.(2018). Survive or perish: Investigating the life cycle of academic journals from 1950 to 2013 using survival analysis methods. Journal of Informatics, 12(1),344-64.

Lowe, R. (2012). The changing role of the academic journal: The coverage of higher education in History of Education as a case study, 1972–2011. History of Education. 41(1), 103–115.

Mabe, M., & Amin, M. (2001). Growth dynamics of scholarly and scientific journals. Scientometrics, 51(1), 147–162.

Mabe, M. (2003). The growth and number of journals. Serials, 16(2), 191–197.

Kousha, K., Thelwall, M., and Abdoli, M. (2012). The role of online videos in research communication: A content analysis of YouTube videos cited in academic publications. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(9), 1710-1727.

Soames, Scott. 2003. Philosophical Analysis in the Twentieth Century,

Volume 2: The Age of Meaning . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

D’Souza, B., Kulkarni, S., and Cerejo, C. (2018). Authors’ perspectives on academic publishing: initial observations from a largescale global survey. Sci Ed, 5(1), 39-43.

Tvrznikova, L. (2018). Case for the double-blind peer review. ArXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.01408