|

The Digital Outlaws: Hackers as Imagined Communities * -

Henning Ziegler

(bio)

The month was May, the year was 2000, and the loss was one of the largest amounts of money ever caused by a worm in computer history. On Monday morning in early May, if you had a Windows system running at work, there was probably a message with the unsuspecting subject "I love you" in your Outlook mailbox. The message text read "kindly check the attached love letter coming from me." High as a kite, you would have opened the mail (unless you were really sure that nobody would send you a message with that subject, in which case you probably would have opened the love letter anyway). But what would have followed your click on the love letter would have made you rapidly come back down to earth: the attached file love-letter-for-you.txt.vbs was not a love letter at all, but an internet worm (worms are these little programs that can self-replicate and spread through the internet very rapidly, usually via Microsoft Outlook programs). The "I love you"-virus, as it came to be known, sent itself to each address in your Windows system address book and dropped an .htm-file and an mIRC (a internet chat application) script on your computer as alternative ways for self-replication. So in that week of May, the worm spread rapidly to millions of Windows users, damaging their systems by changing file types to .vbs-endings and copying itself each time they would try to execute one of these 'infected' files. By a love letter that had turned into a menace to your personal (if digital) belongings, these users suddenly got acquainted with the dark, the vulnerable, and the uncanny side of the 'Web:' Computer help lines were busy and people were just plainly scared. Yes, you had been told by computer security experts never to give out your private address online since 'stalkers' might hunt you in real life (ironically, of course, 'spyware' finds out your private information for other companies). But a love letter turning into an evil worm on the spot-that had been unheard of. Of course, this story is highly simplified. In fact, it only shows one assessment of the strike of the "I love you"-virus-that of the media and the anti-virus company 'analysts.' Ian Hopper, journalist with CNN, chose to aptly title his feature about the worm "Destructive I Love You computer virus strikes world wide." Hopper (2000) describes how the "self?propagating and destructive" virus "wrought hundreds of millions of dollars in software damage and lost commerce." He quotes computer security expert Peter Tibbett of ICSA.net, who estimated that "the price tag (of the virus attack) would exceed $1 billion by Monday morning" of the week after the worm had first been discovered. Interestingly, hackers, the people whose programming skills allegedly gives birth such viruses, have largely relativized such menacing accounts of the "I love you"-attack. Frans Faase, a hacker from the Netherlands, has analyzed the virus source code in detail, and he has made his findings available on the internet. Faase concludes his code analysis by saying that "the virus does not contain all kinds of dirty tricks that the Anti?virus software people claim it to have" (Faase, 2000). And he goes on to say that the "virus was never intended to be anything more than a practical joke. It is also not the most evil virus one can think of. It does some harm, but there are some simple modifications which would make it much more harmful." The "I

love you"-incident of May 2000, in my mind, highlights a great

number of issues in thinking about digital culture. The virus, it

seems, has been constructed as a dangerous object by the media and

the companies, whereas virus programming seems to be fun in the

eyes of the hackers. With hacking becoming fun, political and cultural

theory of the sort which emphasizes the important role that 'counter-hegemonic'

groups play in social change seems to run into difficulties when

it projects its libratory hopes onto hacker culture. On the one

hand, there seems to be a pathological projection of an 'abject'

(Julia Kristeva) of the electronic age onto hackers by the media

and the general public, and on the other hand hacker culture isn't

political per se, but a multi-layered phenomenon that consists of

multiple 'imagined communities' (Benedict Anderson) that lie within

the power structures of a hegemonic framework. This article, then,

will attempt to read hacker cultures in terms of hegemony, and it

will show that the supposed "increasing democratization"

(Landow, 1992, p. 277) for society through the internet lies entirely

within the logic of hegemony as it has been developed by Ernesto

Laclau in Laclau & Mouffe (1983). Hacker groups with practices

as diverse as the Legion of Doom, the Billboard Liberation Front,

or the Electrohippie Collective constitute many intertwined, antagonistic

movements that are spoken for and spoken about. In the following

pages, I will attempt to describe these communities and the images

that are projected onto them and that they project onto others.

With this said, it should be clear that I regard any definition

of hackers (such as being antagonistic to crackers, etc) as quite

pointless: it is the purpose of this article to describe the semiotic

fight of the term, not to state a scholarly definition. Without

the help from influential hacker figures, this endeavor, of course,

would have been impossible. But with the many comments that I got,

I hope that this paper will shake some of the established ways of

thinking about hackers and digital culture a little, and maybe even

lead on to a more grounded discussion about the political in the

data sphere. I think that, as will turn out, even if hackers are

not the 'new hope' for that Marxist revolutionary subject which

we've been looking for so long, there are other people that are

sneaking through the contested terrain between hacking and political

action-hacktivists-and that what they are doing might constitute,

to my mind, a play of resistance.

Hackers appeared as a mass cultural phenomenon in the United States around 1990. The so-called hacker crackdown inscribed itself into the American psyche at that time, a large-scale FBI hunt of computer criminals who were accused of having crashed the AT&T telephone system. The way in which hackers surfaced in U.S. culture, however, had little to do with the positivistic way in which the term was first employed by the model train hobbyist at MIT's Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) in the early 60s. In fact, looking at Hollywood movies as indicators for mass cultural perception of reality, I would argue that technology in the late 1980s was portrayed on the screen as a finally uncontrollable, dark menace-the gooey chrome of Terminator 2, which leaves the individual vulnerable and disempowered. Hackers, though, were ambiguously constructed: They were the strange technology wizards who, as 'good Americans,' fight for civil liberty, but they were also people with questionable motives, not hesitating to sell their technical expertise to the 'bad guys.' In addition, the political was generally reduced to activism-in the simplified logic of Hollywood, the state apparatus becomes a shady force that randomly blocks you from 'restricted areas.' In movies such as Tron (1982), War Games (1983), and finally in the 1990 release of Renny Harlin's Die Hard 2, all these issues figure prominently. But since Die Hard 2 coincided with the hacker crackdown, let's look at how that movie took to the screen Bruce Sterling's prediction that "hacking will kill people soon."

Another notion that is deeply connected to hacking is 'trespassing,' a concept which Die Hard 2 employs in several ways. Individuals are trying to gain access to forbidden spaces, and an authority blocks this access for no apparent reason: the usually crowded public space (the airport arrival halls, bars, cafés) is set against the randomly sealed-up space that is owned by someone else. Throughout the movie, the notion of trespassing is connected to the uncanny when McClane actually manages to cross over into the forbidden. He then finds himself within dark surroundings, as in the gunfight between the screeching belts of the luggage transport system in the 'bowels' of the airport. The hackers, of course, are already on this other side; close to the machine, they use it as a camouflage for their activity. McClane is randomly blocked away from this space, and this contingency of access denial is personified in the figure of airport police chief Lorenzo (Dennis Franz). Lorenzo is a fat annoying figure that sits in McClane's way wherever he goes, attentive only when his own personal position within the system is endangered by his own boss--bureaucracy personified. Arguably, in connecting this bureaucratic character with McClane's crossing over into the forbidden, Die Hard 2 establishes a hacker mindset in the viewer: the movie can be read in terms of the continuing attempts to get access by McClane, and, of course, by the hackers to get access to the tower, which positions them close to McClane. Not surprisingly, then, the movie's imagery of hackers is highly ambiguous. On the one hand, since we're dealing with a Hollywood movie, to some extent, hackers simply are the bad guys. The Colonel (William Sadler), the leader of the group of hackers, is a blonde, Teutonic man with an evil stare, and the "victory for our way of life" which he proclaims right before their B747 explodes, seems to be a victory for smoking dope in the back of a plane, and for partying in the tropics on money that you've been paid by a drug mafia figure. The political motivation of the hackers in bringing Esperanza safely to the tropics is summed-up in the statement "I've seen enough snow in my lifetime." But then again, hackers have good traits in Die Hard 2. 'Social engineering,' for example, is a strategy that both McClane and the hackers use: Captain Grant (John Amos), the leader of a military platoon that apparently comes to safe the situation, turns out to be a member of the hacker group in the end. And John McClane, pretending to be a local policeman, 'socially engineers' his way to a fingerprint of a dead hacker. The movie makes clear that a hacker is not "some punk stealing luggage" (Lorenzo) but someone who can influence technology on a very deep level when the hackers not only shut down the lights of the runways, but also reset the ground for a plane at minus 200 feet-they turn into terrorists who can deeply influence a whole world structure that relies heavily on technology. "It's like the tower isn't there," the 'good guys' have to realize, before they send in a 'good' hacker of their own: an African-American tower technician elegantly hacks a beeper tower to sending radio signals to the pilots. So when McClane's wife Holly tells him at the very end, "They told me there were terrorists at the airport," McClane somewhat sympathetically ends the movie on the note: "They are that too." But let's not forget about the limits of Die Hard 2. The movie might portray hackers ambiguously and it might bring to mind a relatively complex picture of the Hollywood projections of uncanny technology, but the whole source for the terror and the fighting, the political problems of the United States with South American drug cartels, entirely falls into the background as the action continues to develop. Generally, the movie is more about personal activism, freedom, empowerment to get access, and fun, than about political problem solving. The politician Esperanza is not brought to a fair trial but simply killed-a fact that might point to the limits that anyone who has political ambitions to inscribe into hacker culture might have to face with. But let's leave the contradictory Hollywood mindset of the late 1980s aside and see whether the 'technological uncanny' that has figured prominently in Die Hard 2 will get us anywhere when employed to the really existing internet and its digital outlaws. Theorizing the Uncanny Data Space

There's an important

difference between saying that something is constructed and saying

that the image of technology in Hollywood movies is merely an dark

fantasy. And there is also a difference between relativizing hacker

culture as a complex, empty signifier and saying that hackers as

a menace (crackers) simply don't exist. There are very real reasons

for the public angst. Think of the horror that stood at the very

beginning of the internet. In 1957, the Soviet Union succeeded in

launching a satellite into the orbit, and the Soviets won the 'space

race' against the United States. America fell into the so-called

'Sputnik shock' and, once it was on its feet again, founded the

Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA) as a part of the Department

of Defense. The computer history Fire in the Valley clearly assesses

that the purpose of the network of computers that the ARPA researchers

put up back then had been from the start "to build a defense-research

communication channel robust enough to survive a nuclear attack"

(Freiberger & Swaine, 2000, p. 209). And this 'horror of the

beginning' has technologically continued throughout the history

of the internet. The free flow of information on a global computer network is essentially hard to control, thereby adding to the dark twist of the Web. Corporations take great pains to secure their 'unfree' data, and some of them are selling security to private individuals in the form of encryption software or firewall programs. So, with vulnerability being a central issue in the thinking about an uncanny logic of the data sphere, the nature of information turns into a contested, attacked, secured, and fought about concept. Two projects, I think, fit particularly well to illustrate this point. The first one is Cryptome (http://www.cryptome.org), a website that specializes in making restricted information available to the public. On the project's internet page, the purpose of Cryptome reads: "Cryptome welcomes documents for publication that are prohibited by governments worldwide, in particular material on freedom of expression, privacy, cryptology, dual?use technologies, national security, intelligence, and blast protection--open, secret and classified documents--but not limited to those." Browsing through the website, one can find, for example, recent documents from the Al Qaeda trials, access to which has actually been bought up by Cryptome. The site's aim for providing access to restricted information for individuals presupposes, of course, the two notions that there is 'secret' information and that the individuals' vulnerability is not to have access to that. Furthermore, Cryptome constructs a state apparatus that is vulnerable in that there finally is a way to get access to its secrets (by the cunning of crackers, mostly). These two-layered vulnerabilities surfaced again in an e-mail conversation that I had with John Young, the maintainer of Cryptome. Young wrote that Cryptome is "political in that we aim to offer information access different from what is dispensed by authoritarians-all of whom are censors and avid suppressors of political action" (personal communication, May 1, 2002). In the context of digital art, a project of the San José-based collective C5 is interesting when looking at the contested nature of information on the Web and at the vulnerabilities that the free flow of information causes. For Lisa Jevbratt's 1:1 (http://www.c5corp.com/ projects/1to1), for example, C5 software robots traveled in data sphere, systematically evaluating the content of IP addresses (an IP address is the number that a 'Web' address stands for, and it consists of four numbers from 0 to 255). During the first run of the bots in 1999, what appeared on the 1:1 maps of data space were mostly governmental or military pages that often required passwords-the map gave you an uncanny feeling about the 'real' nature of its content instead of the friendly and colorful image within your everyday Yahoo! frame. In another project called Softsub (http://www.c5corp.com/projects/softsub), C5 'data-mines' your computer at home and feeds seemingly banal information about your directory structure and desktop layout into a program that calculates your machine's closeness to other desktop configurations. Softsub, therefore, hints at the "lack of awareness (of the average computer user) about how extensively personal information that has been collected is used on the Net and to whom this information is shared" that John Young finds (personal communication, May 1, 2002). With cell phones increasingly turning into a fashion product (Nokia, for example, makes more money off the selling of plastic covers than off technology), 'vulnerability,' of course, also reaches into cell space. In the Hacker Crackdown, Bruce Sterling cautions that "eavesdropping on other people's cordless and cellular phone calls is the fastest growing area in phreaking (phone hacking) today" (Sterling, 1994, pt. 2).. It seems comparatively easy to fake your identity on a cell phone, a hack that enables you to hide your location from 'authorities' (drug dealers like this) and to get free calls. In fact, any attentive reader of issue 73 of the Datenschleuder, a magazine of the Berlin-based Chaos Computer Club (CCC), will learn how to lead denial of service attacks (DoS) against Nokia cell phones.** Interestingly, the uncanny of cell- or telephone space has a historical dimension: In the 1870s, the early days of telephony, phones were regarded as spooky gadgets-mysteriously speaking machines that hardly anybody would dare talk to (see Sterling, 1994, pt. 1). Only much later, telephones came to be regarded as a medium with a real person on the other side. So the uncanniness stayed on with each time that the technology took another step forward: telegraph boys, maybe being the first hackers, had fun wiring up the wrong people with each other until, in 1878, Bell fired them all and legions of professional female operators stepped in. This suggests

that hackers themselves, of course, can be 'bad guys' as well, and

contribute to vulnerability on the Web. The National Institute of

Standards and Technology, in a famous document entitled "Threat

Assessment of Malicious Code and Human Threats," describes

hackers in the following way: "Today, computer systems are

under attack from a multitude of sources. These range from malicious

code, such as viruses and worms, to human threats, such as hackers

and phone "phreaks." The document goes on by saying that

malicious "code (...) attacks a system in one of two ways,

either internally or externally. (...) Human threats are perpetrated

by individuals or groups of individuals that attempt to penetrate

systems through computer networks, public switched telephone networks

or other sources" (Bassham & Polk, 1994). What, to the

technologically illiterate, seems to be a Die Hard 2-construction

of a menace to society, maybe becomes more understandable when you

imagine someone regularly searching through your trash. Someone

reads every torn bill or letter that you threw away. You'll realize

that this person could find out quite a lot about you, only until

now you never thought that someone might actually search something

as 'abject' as your trash can. Well, some hackers would do that,

and it's called 'trashing.' If you're a little frightened now about

your trashing practice, you can imagine the uncanny that computer

network administrators feel when they notice a cracker in their

system... Bruce Sterling, summing-up what I've said above, writes that the "extent of this vulnerability (of data space) is deep, dark, broad, almost mind-boggling, and yet this is a basic, primal fact of life about any computer on a network" (Sterling, 1994, pt. 1). In my mind, this vulnerability can be grasped with Julia Kristeva's notion of 'the abject' which she develops in her book Powers of Horror. Using her famous example of the skin on the surface of milk which causes sickness, Kristeva writes that there "looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable" (Kristeva, 1987, p. 1). If we see crackers as the abject of the electronic age, they constitute that "massive and sudden emergence of uncanniness" (p. 2) and a "real threat (that) beckons to us and ends up engulfing us" (p. 4) that Kristeva talks about. One key passage explicitly connects the criminal to abjection: "it is not the lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection, but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The inbetween, the ambiguous, the composite (...). Any crime, because it draws attention to the fragility of the law" (p. 4). The construction of hackers by the media and society, it seems, fits well into this framework. But Kristeva also hints at the playful aspect of hacking that Frans Faase, the hacker who commented the "I love you"-source code, has already described: the abject "acknowledges the impossibility of Religion, Morality, and Law-their power play, their necessary and absurd seeming. Like perversion, it takes advantage of them, gets round them, and makes sport of them" (p. 16). The counterstatement against hackers as the playful abject of data space is the aseptical software figure of Dr. Solomon, the white medical person who periodically cleans your hard disk, thereby ritually and redemptively swiping it clean of any abject data. Finally, accounts of cracker arrests can be grasped within the notion of the abject as well. Leftist, whose parents were "traumatized" when he was arrested during the hacker crackdown, and Terminus, who was arrested as well to "the stark terror of his wife and children," become the abject in the family-the "threating otherness" (Kristeva) that finally turned out to be within (Sterling, 1994, pt. 2). How Hackers see Themselves

Hackers, in

the way in which they imagine themselves and their friends (and

enemies), are a complex phenomenon that entails all the difficulties

of analysis that hold true for any other subculture. My way through

this maze will be that I'll describe some of the quite problematic

self-definitions that prominent U.S. hackers hold about themselves

and trace those definitions back to mythical constructions such

as the digital outlaw. Hackers in the United States are, of course, much more critical about themselves than the stereotypical, if somewhat complex images of Die Hard 2 suggest. An issue that they are very critical about is internet access (without which, of course, they wouldn't be able to hack at all). American hackers, it seems, share a common concern about the 'freedom of information' and about possible restrictions on the openness of the data sphere and they also share certain premonitions about the Foucauldian workings of power within that sphere. Eric S. Raymond, a famous Linux programmer and author of the influential book The Cathedral and the Bazaar, holds that the data sphere is "open in that it's easy for lots of people to reach and difficult to control" (personal communication, April 29, 2002). Raymond goes on to say that, in the data sphere, he sees "the possibility to help individuals become better able to acquire knowledge and disseminate their thoughts to others" which should give them "more leverage relative to governments and corporations." And John Young of Cryptome says that "there are sustained attempts to restrict (the internet) becoming and remaining fully open and to instead use it for intellectual, political, social and economic control" (personal communication, April 28, 2002). So although both hackers imagine the Web as an essentially open space, the limits of that space are clear in that governments and corporations are constructed as blocking the free 'dissemination of thought,' and that the Web is used for controlling purposes by an imagined state apparatus.

The critical view that already surfaces in such hacker statements about control and informational freedom finds an expression in the antagonistic construction of 'the cracker,' the enemy of hacker culture who illegally breaks into computer systems. The Mentor, in his Hacker Manifesto, plays with this construction when he confesses: "Yes, I am a criminal. My crime is that of curiosity. My crime is that of judging people by what they say and think, not what they look like" (The Mentor, 1986). Eric Raymond discussed the construction of the hacker/cracker distinction at length in an e-mail conversation with me. He holds that there "is a large, open culture of hackers (...)-technologists who invented the Internet and keep it running (...). We're no threat to anybody. There is a much smaller culture of crackers, very secretive and in parts actively criminal." Raymond traces this antagonism back to the split between the early Personal Computer hobbyists and the campus subculture of minicomputer?based hacker groups-interestingly, many expressions of hacker jargon such as 'trojan' were coined in the 1960s college environments. Nevertheless, what can be seen in this construction of the cracker, in my mind, is that hackers as a subculture have their very own antagonisms. They see themselves as 'the good technologists' with certain codes and laws, while a group that they construct as 'crackers' (or 'script kiddies') disturbs their system and does not 'respect borders, positions, rules,' drawing attention to the emptiness and 'fragility' (Kristeva) of their own self-construction-hackers, so to say, have their very own abject. It is within this terrain that the notion of 'ethical hacking,' which has become a real buzzword again, has emerged in the 1980s: ethical hacking, read as an attempt to unite the binarism of hacker vs. cracker, is an attempt to dismiss the abject of hacker culture by positing an inherent ethics of hacking practice. The concept itself goes back to Stephen Levy's book Hackers-true hackers, Levy writes, have a "philosophy of sharing, openness, decentralization" (...). They "were adventurers, visionaries, risk-takers, artists ... and the ones who most clearly saw why the computer was a truly revolutionary tool" (Levy, 1984, p. X). Free access to technology, the freedom of information, mistrust against authority, and the view that computers can change life for the better are the basic columns of Levy's ethics. Not surprisingly, these values have been rediscovered by books such as Raymond's The Cathedral and the Bazaar and Pekka Himanen's The Hacker Ethic. Raymond's overall argument in Cathedral is nicely summed-up by Linus Torvald's (the programmer of the kernel for the 'free' Linux operating system) law: "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow" (Raymond, 1999, p. 41). As a believer in the free market, Raymond develops a strategy for marketing Linux applications under the brand of 'open source' software, an overall aim that is shared by Pekka Himanen in Hacker Ethic. Himanen holds that "computer hackers can be understood as an excellent example of a more general work ethic-which we can give the name the hacker ethic-gaining ground in our network society" (Himanen, 2001, p. 7). This ethic, unlike the Weberian work ethic, holds that meaning "cannot be found in work or leisure but has to arise out of the nature of activity itself" (p. 151). Both Himanen and Raymond suggest an ethics of play which, at the same time, makes the individual work. Again, what we have here is the construction of laws and structure that 'real hacking' was meant to run orthogonal to. The above discussion suggests some problems with Bruce Sterling's assessment that "there is an element in American culture that has always strongly (...) rebelled against all large (...) companies" and that a "certain anarchical tinge deep in the American soul delights in causing confusion and pain to all bureaucracies, including technological ones." (Sterling, 1994, pt. 2). In fact, throughout the U.S. hacker culture, an image of the electronic frontier is still prevalent that could be viewed as the positive imaginary of the unconscious of hacker culture that gets blown up as the hackers continue to face the 'threatening otherness' (Kristeva) within their own tribe. In 1990, John Perry Barlow, together with Mitchell Kapor, founded the aptly named Electronic Frontier Foundation (http://www.eff.org), an organization to promote the right of free speech in cyberspace. Barlow, in his famous Crime and Puzzlement Manifesto, works a lot with imagery of the frontier and the century West: "Cyberspace (...) has a lot to do with the 19th century West. It is vast, unmapped, culturally and legally ambiguous, verbally tense (...), hard to get around in and up for grabs" (Barlow, 1990). Bruce Sterling, in The Hacker Crackdown, uses similar expressions when talking about the nature of the data sphere. Sterling asserts that hackers are "soaked through with heroic anti-bureaucratic sentiment" and that they "long for recognition as a praiseworthy cultural archetype, the postmodern electronic equivalent of the cowboy and mountain man" (Sterling, 1994, pt. 2). Furthermore, he talks about data space as the indefinite place 'out there,' and his analysis culminates in the view that "a Personal Computer can be a great equalizer for the techno-cowboy-much like that more traditional American "Great Equalizer", the Personal Sixgun" (Sterling, 1994, pt. 3). So I think one can generally assert, with Sean Cubitt, that the anonymity of the U.S. data space "has given rise to (...) the most uncompromisingly individualist of cultural icons: the outlaw, the phreak, the cowboy, the frontier." As Cubitt goes on to say, the "very Americanization of matrix vocabulary indicates less its domination by North Americans than the power of the North American mythography of westward expansion and rugged individualism in the new context" (Cubitt, 1998, p. 87). Since the frontier is a contested terrain, however, multiple antagonisms around the hacker ethic are played out between fragmented hacker cultures underneath the blown-up imagery of the 'vast open spaces.' The principle of the freedom of information is contested as the programming of Linux is basically free, but then again the most often visited sites about Linux applications and information about the free software scene, slashdot.org and Freshmeat, are owned and run by a company-VA Linux systems. The principle of judging people on what they know is equally contested by the tribal logic of hacker culture: This logic fosters elite thinking and boasting, since "the way to win a solid reputation in the underground is by telling other hackers things that could only have been learned by exceptional cunning and stealth" (Sterling, 1994, pt. 2). Handles that contain the words 'master' or 'genius' are frequently used, and European hackers (who often despise of such handles) are constructed as "hash-smoking anarchist hackers who had rubbed shoulders with the fearsome big-boys of international Communist espionage" (Sterling). That computers can change life for the better is highly relativized by issues of access and the practice of carding which is (at least to crackers) one of the best ways for an arguably simplistic betterment: In order to get more money for new computers, you spy on someone's credit card transactions to later use the card yourself. Finally, and not surprisingly, hackers also have constructed their very own technological and social uncanny: the figure of Microsoft head Bill Gates. A hacker site (http://www.enemy.org) constructs Gates, as Slavoj Žižek aptly writes, as the "Master who is simultaneously our common peer, our fellow-creature, our imaginary double and-for this very reason-phantasmatically endowed with another dimension of the Evil Genius." (Žižek, 1999, p. 349). So, given all those antagonisms, hacker culture generally looks highly fragmented and doesn't seem to serve too easily as a subculture onto which one can project hopes of a revolution (as Negri & Hardt have tried to do recently with their update of the term 'virtuality'). If anything can serve as a subject of resistance at all, that might work best with a recent phenomenon that runs so orthogonal to digital culture that even the hackers don't think of as 'real' hacking. What Hackers don't call Hacking: Hacktivism

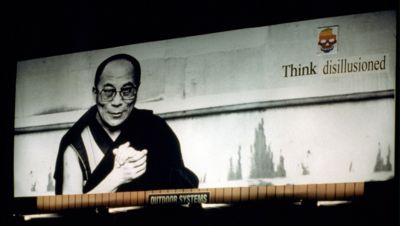

Hacktivism has its historical precursors in the beginnings of cultural jamming. Critic Mark Dery describes this notion as the use of a "guerrilla semiotics-analytical techniques not unlike those employed by scholars to decipher the signs and symbols that constitute a culture's secret language" (Dery, 1993). Dery goes on to say that the culture jammers' question is: "Who will have access to (...) information, and on what terms? (...) In short, will the electronic frontier be wormholed with 'temporary autonomous zones' (...) or will it be subdivided and overdeveloped by what cultural critic Andrew Ross calls "the military-industrial-media complex" The people first to prominently make use of this 'guerrilla semiotics' were probably Jack Napier and Irving Glikk (both names are pseudonyms) of the Billboard Liberation Front (BLF) in San Francisco. In 1977, they started to 'improve' existing billboard messages, starting out from the insight that the internet is "a commodity which is being carved up by commercial interests more each day" (personal communication, May 1, 2002). In their Manifesto, the BLF people ironically write that "the Ad holds the most esteemed position in our cosmology" and that, therefore, "to Advertise is to Exist. To Exist is to Advertise" (Napier, 1999). Perhaps a recent action of the BLF can illustrate this: In 1998, the group changed Apple's "Think Different" claim into "Think Disillusioned" on a famous billboard ad starring the Dalai Lama, and it altered the company's rainbow-colored apple logo into a skull. So I think it can be argued that the BLF is quite conscious of the complex Foucauldian workings of power in society: jamming billboards, their Manifesto explains, is like messing with "the messenger RNA of capitalism." And it's fun, too.

The Electrohippies (http://www.fraw.org.uk/ehippies) are a collective that has taken such jamming practices into the data sphere. Their latest action is a 'virtual sit-in' called "Netstrike" against the Israelian government that is technically accomplished by using DoS-attacks-anyone with a modem and a computer can access a site which repeatedly sends requests to the Israelian government's website until it finally crashes (http://www.geocities.com/netstrike4palestine). The ehippies' conception of the data sphere is complex in that it includes all connected electronic media "that enable the dissemination of information and intellectual property: telephones, fax machines, information technology, radio, and the Internet."(Electrohippies, 2002) Interestingly, the collective's 'guerilla semiotics' starts out with its very name-their resignification of the term 'hippie' creates a dynamic meaning that serves well in the partly mocking and partly serious attempts to semiotically jam the data sphere. Coming from an activist background rather than a computer hobbyist scene, the Electrohippies have an important concern that the 'real' hackers and crackers leave out: the connection between the real world and the data sphere. According to their website, the "corporate forces that are damaging the world (...) are the same corporate forces that are creating this new information society because it assists their purposes. Therefore, tackling the inequalities created by the new networked society before they become established is as important as tackling real world problems today." The 'hacktivismo' movement (http://www.hacktivismo.com) continues what might be called a notion of 'electronic civil disobedience' (ECD). The group states in their manifesto that everyone shall have the "freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice" (Hacktivismo, 2001). Electronic civil disobedience has become a famous concept through the actions of the Zapatista movement: The Zapatista rebellion in the Chiapas region in Mexico largely depended on the use of hacker techniques and technology. With the traditional methods of public discourse being blocked or exhausted, the Zapatistas came up with the Floodnet tool, DoS software that can be downloaded from their website (http://www.thing.net/~rdom/ecd/ecd.html). The Zapatistas and the concept of ECD also draw attention to the interplay between economical and political structures that depend heavily on the global internet: "Blocking information conduits is analogous to blocking physical locations; however, electronic blockage can cause financial stress that physical blockage cannot, and it can be used beyond the local level" (Hacktivist, 2001). What has become clear from the statements of the hacktivist groups, in my mind, is their concern about the connection between real political action and activism on the internet. Hacktivists don't serve as easily as hackers as the latest 'counter-hegemonic' group, since their practice is at times equally self-mocking as it mocks its target-the . So the self-conscious technological play of hacktivists suggests the way in which 'hacking' could actually constitute a radical cultural practice and a jams the terrain between the virtual and the real. Conclusion: Hacking as Playful Resistance

I have shown throughout this article that hackers cannot serve as the new 'counter-hegemonic' subject that Hardt & Negri (2000), among others, project onto digital culture's outlaws. The way in which Hollywood movies such as Die Hard 2 in the early 1990s constructed hackers as an uncanny menace might have lead the way into to such romanticizing fantasies that finally employ myths (such as the openness of digital space) that the cultural critics of the Left set out to dismantle. In fact, hacker culture is much more fragmented and antagonistic than these critics hold, so that it lends itself, in my mind, much more readily to Ernesto Laclau's theory of hegemony than to hopes for a revolution. Hackers' pejorative statements about 'crackers' or 'script kiddies' point to the existence of hacker culture's own abject, and, in Laclau's terms, to the "limits of all objectivity" (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985, p. 122)-to define the 'fullness' of hacker culture is impossible. In the semiotic struggle about the culture, however, the self-conscious technological mockery of hacktivists such as the Electrohippies constitutes a cultural practice that more radically jams the virtual and the political. Hacktivism, one might say, constitutes a necessary, playful reaction by digital activists to Foucauldian power structures, once the universality of hegemony has been accepted. The importance of play at the crossroad between the political and the data sphere has already been hinted at by Sean Cubitt when he states that the playful "mode of reading, its potentials and limitations, is central to reading in both the Internet and multimedia" (Cubitt, 1998, p. 15). Can one, then, make sense of hacktivism as playful resistance? It's a little more complex, I think. James Carse has developed an interesting language in talking about play that might help to see hacking as a playful culture that can serve as a field that is, in a sense, not as rooted in power as Capitalism, in that it tweaks the power structures and causes unforeseen outcome. Carse differentiates between finite and infinite games-the latter continue without results whereas the former have a winner and a loser (zero-sum games). Hacktivists are the finite gamers in this language: instead of killing their opponent, their game continues, and it changes its rules as it does that. The Toywar of the hacktivist/artist collective etoy is a good example here: etoy won a virtual domain name war against lawyers of eToys.com because of their strategy of changing rules as the games continues, preserving the openness of the play (http://www.toywar.com). Etoy (or the Electrohippies, or the Zapatistas, or BLF) can easily be called 'just steamy young males' without real political aims, so it's vital to understand how Carse could think of play as being "political without politics" to see where my main argument, perhaps, is finally going (p. 47). Finite play, for Carse, is like theater: the participants walk home after the show and become liberal subjects again. But add hegemony/antagonism to the picture and you get the infinite game of cultural resistance: it is one consequence of the insight into the universality of antagonisms that constitute hegemony. Similar to the conflict in a drama, the antagonisms at the heart of society are irresoluble. Hacktivists have taken this lesson to heart and, so it seems, they are trying their best to playfully expose the logic of Capital that increasingly rules the digital world in order to evoke that (always already nostalgic) dream of the early Tech Model Railroad Club hackers at MIT: to control things yourself.

*This article

has benefited from criticisms by members of the Nettime and Rohrpost

mailing lists, most notably Harald Hillgärtner, and from criticism

from my teachers Margaret Morse and Winfried Fluck. I am particularly

grateful for comments from the legendary GNU/Linux programmers Richard

Stallman and Eric Raymond, Jack Napier of the Billboard Liberation

Front, John Young of Cryptome, and from the legendary hacker John

"Cap'n Crunch" Draper.

|

||

In

Die Hard 2, the tough, everyday guy John McClane (Bruce Willis)

is waiting to pick up his wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) at an airport

near Washington D.C. On the same evening, however, the plane of

Ramon Esperanza (Franco Nero), a South American politician who is

being brought to a drug-related trial to the U.S., is scheduled

to arrive. A group of hackers, hired by Esperanza, take control

of the airport technology to land his plane, demanding a B747 to

escape to 'the tropics' together with the politician. The motive

of the dark technology is introduced in the movie by an old lady,

who, pointing to her (then brand-new) cell phone, asks McClane's

wife on an airplane, "Isn't technology wonderful?" The

remaining two hours of Die Hard 2 can be read as a boldly negative

answer to this question. In fact, the movie opens up a dichotomy

between mere mechanical tools and electronic technology. This dichotomy

becomes apparent as, in the first scenes, McClane's car is towed

and he starts an argument with a New York police officer (who neither

cares about McClane's Los Angeles Police badge nor about the date

being Christmas Eve). The towing scene works as a counter-statement

against the rest of the movie: the human operator still has the

power over her tow truck-McClane's anger is directed against her,

not against the machine itself. Telephones, on the other hand, are

a dangerous and unpredictable technology in the movie. The notoriously

scarce pay phones are almost a running gag, and cell phones can

even threaten your life: as McClane sneaks up to the hackers who

have barricaded themselves in a small church, his cell phone rings,

giving him away to the crossfire of his enemies. Not surprisingly,

there's not a lot of 'good' technology in the movie. In a classic

scene, McClane is able to press the ejection switch of a hot seat

just in time to escape from an exploding plane. But generally, technology

in Die Hard 2 is constructed as the murky in-between the men at

the switches in the airport control tower and the pilots in the

cockpit. Even the hackers have to experience that it can turn into

a menace when, after they ingeniously hacked a whole airport control

system, their B747 finally explodes-through the manual labor of

John McClane.

In

Die Hard 2, the tough, everyday guy John McClane (Bruce Willis)

is waiting to pick up his wife Holly (Bonnie Bedelia) at an airport

near Washington D.C. On the same evening, however, the plane of

Ramon Esperanza (Franco Nero), a South American politician who is

being brought to a drug-related trial to the U.S., is scheduled

to arrive. A group of hackers, hired by Esperanza, take control

of the airport technology to land his plane, demanding a B747 to

escape to 'the tropics' together with the politician. The motive

of the dark technology is introduced in the movie by an old lady,

who, pointing to her (then brand-new) cell phone, asks McClane's

wife on an airplane, "Isn't technology wonderful?" The

remaining two hours of Die Hard 2 can be read as a boldly negative

answer to this question. In fact, the movie opens up a dichotomy

between mere mechanical tools and electronic technology. This dichotomy

becomes apparent as, in the first scenes, McClane's car is towed

and he starts an argument with a New York police officer (who neither

cares about McClane's Los Angeles Police badge nor about the date

being Christmas Eve). The towing scene works as a counter-statement

against the rest of the movie: the human operator still has the

power over her tow truck-McClane's anger is directed against her,

not against the machine itself. Telephones, on the other hand, are

a dangerous and unpredictable technology in the movie. The notoriously

scarce pay phones are almost a running gag, and cell phones can

even threaten your life: as McClane sneaks up to the hackers who

have barricaded themselves in a small church, his cell phone rings,

giving him away to the crossfire of his enemies. Not surprisingly,

there's not a lot of 'good' technology in the movie. In a classic

scene, McClane is able to press the ejection switch of a hot seat

just in time to escape from an exploding plane. But generally, technology

in Die Hard 2 is constructed as the murky in-between the men at

the switches in the airport control tower and the pilots in the

cockpit. Even the hackers have to experience that it can turn into

a menace when, after they ingeniously hacked a whole airport control

system, their B747 finally explodes-through the manual labor of

John McClane.