|

Does Location Matter? Sakari Taipale (bio)

1. Introduction

1.1 Young people and mobile phones in Finnish society The mobile phone revolution has rapidly taken possession of Finnish society. In 2006, already 97% of all people owned a mobile phone in Finland (Nurmela, Sirkiä, & Muttilainen, 2007, p. 40). Nevertheless, the extensive penetration of mobile handsets does not yet indicate the total absence of disparities in the everyday use of mobile phones. Even if the mobile phones have spread throughout society, the ways of using mobile phones may create some differences, for instance, between regions and generations. In Finland, there is evidence that young people, the residents of metropolitan areas and other major cities stand out from the rest regarding the use of new mobile services and the mobile internet (Nurmela & Ylitalo, 2003; Nurmela et al., 2004; Nurmela, Sirkiä, & Muttilainen, 2007). The differences are not enormous, and it is also noticed that the people of small municipalities are in some respects more active mobile phone users than urban dwellers (Nurmela, J., Parjo, L., & Ylitalo, M., 2003).

This article

approaches this phenomenon from a within-country perspective. It explores to what

extent young people living in different kind of cities and towns use the mobile

phones similarly or not. In the study, the cities and towns are grouped into

two poles according to their level of urbanity. Firstly, the article aims to

find out what are the main patterns of mobile phone use among our respondents in

Finland. Secondly, the article aims to find out the extent of the resemblance

that the young people of urbanised cities and less-urbanised towns have with

each other as mobile phone users. Thirdly, the article tries to bring out the

factors predicting differences and similarities in mobile phone use between the

urban and the non-urban locations.

In terms of

sociological theory, the article is built on studies on urban ways of life and

those arguing for the urbanity of mobile phones as a sociological phenomenon

(e.g. Simmel, 1964; Kopomaa, 2000; Mäenpää, 2001;

Fortunati, 2002; Townsend, 2002; Okada, 2006). In these studies, urban space is

typically regarded as the most fertile location for experimental and versatile

mobile phone use. Being hectic, impulsive, and full of alternatives, urban

space may open up the possibility of more social situations and opportunities

for the inherent use of mobile communication technologies. In contrast to this,

the urban living environment contains several competing means and ways to spend

free time, have fun and socialize with other people. From this starting

point, the study hypothesises that young people in urban cities employ mobile

phones to respond to the demands of a hectic and impulse-rich life. It is said that

the urban technology-mediated lifestyles are nomadic and require a lot of

temporal and spatial coordination (Kopomaa, 2000). Secondly, the article

hypothesises that the use of mobile phones for social and entertainment

purposes could be used more common in less-urbanised locations. In the less-urbanised

locations the mobile phones could be employed with the purpose of compensating for

the lack of physical proximity and alternative sources of entertainment. To

tackle these issues, the article takes advantage of quantitative survey data

collected in 2005 (N=421). The data consists of young people aged 15 to 25

years living in four cities and towns in Finland. 1.2 Research

questions

Three research

questions are set for the study. The questions are formulated to discover

similarities and differences in the use of mobile phones among young people,

and to explain possible variations between the urbanized and the non-urbanized

locations. The questions are as follows: Q1: What

are the main patterns of mobile phone usage among our respondents? Q2: Do

the patterns of mobile phone use differ between the urban and the non-urban

locations? Q3. What

factors explain the differences and similarities in the use of the mobile

phones between the two types of locations? The first research

question is descriptive by nature and to some extent confirmatory. It addresses

the issue of whether the main patterns of mobile phone use are similar to those

found previously (O’Keefe and Sulanowski, 1995;

Fortunati & Maganelli, 1998). The second question

aims to discover potential differences between the two groups. In this case, the groups are formed by those young people residing in different

socio-cultural locations; some in rather urbanised and hectic cities and other

in less-urbanized small towns. The third research question is the most

challenging and explanatory. It tries to discover what are the determining

factors explaining differences and similarities in the patterns of mobile phone

usage between the two types of cities and towns. 2. Theoretical Background 2.1 Young people

and mobile phones in Finland

Despite the fact

that young experts and careerists were the first adopters of the technology in

most countries, young people have inspired sociologists as a subject of

research the most (Fortunati & Manganelli, 2002).

In this study, the term ‘young people’

is used to refer to 15 - 25 year-olds. Defining the term is essential, as

previous studies have pointed out that children, pre-teens, teenagers and

pre-adults use mobile phones quite differently. The ways of using the mobile

phone begin to diversify and become more complex during these particular years

and even at a younger age. Mobile use for entertainment, including all kinds of

off-line use, is challenged by more instrumental, affective and expressive uses

(Oksman & Rautianen,

2002; Castells et al., 2007). Until today, an array of studies about young

people of all ages has been carried out. Various aspects of texting culture,

relationships between parents and children, and security issues have been analysed

rather extensively, especially through qualitative methods. (e.g.

Kasesniemi & Rautiainen,

2002; Oksman & Rautiainen,

2002; Skog, 2002; Fortunati & Manganelli, 2002; Höflich & Rössler, 2002;

Green, 2002; Kasesniemi, 2003; Yoon, 2003; Ling,

2004). In contrast, there

is a considerably smaller number of quantitative

approaches attempting to model the patterns of ICT use and identify their

antecedents (cf. Fortunati & Manganelli, 1998; Wilska, 2003; Miyaki, 2006).

Numeric accounts have mostly focused on ownerships rates, ‘early’ and ‘late

adopters’, mobile ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’, the amount of mobile phone use, and the

relationship between mobile telephone and internet

use. (Leung & Wei, 1999; Rice & Katz, 2003; Davie,

Panting, & Charlton, 2004; Park, 2005). Much less is known about

differences in the patterns of mobile phone use, and whether they are related

to the socio-geographical locations of use (Fortunati, 2002; Campbell, 2007;

Castells, et al., 2007). Nevertheless, earlier

studies imply that young people use mobile telephones in the most varied manner

(Castells et al., 2007, 167). The results of Finnish studies also support this observation

(Kasesniemi & Rautiainen,

2002; Kasesniemi, 2003), although researchers have

also noted that a section of young people consider this type of social standing

to be a form of social burden, something hard to identify with (Coogan & Kangas, 2001). This

is to say that young people should not be considered to be a consistent mass of

ICT users, who are all in an equal position as mobile phone users. Those living

in the urban cities, particularly in metropolitan areas, are most likely to have

the greatest variety of mobile phone services ready at hand. For example, in

many countries, Finland included, urban dwellers have been the first to be

within the coverage area of the G3 mobile network that allows fast data

transmission, mobile internet, and a variety of new

mobile services. To sum up, if we

only look at the mobile phone and service penetration rates it is not possible

to get the whole picture of equalities and inequalities in the use of the

mobile phones. The mobile phone ownership rates are showing high figures for

all age cohorts and for every part of the country (Nurmela

et al., 2007). In terms of ownership rates, only women aged 60-74 are slightly,

although not dramatically, lagging behind the rest of the population. At the turn

of the new millennium, it was noted that some Eastern and Northern provinces

register slightly lower increase rates in mobile phone ownership (Nurmela et al., 2000). In the absence of newer figures, it

can be still assumed that these provinces have since caught up.

2.2 The patterns

of usage and urban space

In which ways do

young people then use mobile telephones? What are the main patterns of usage according

to earlier literature? Fortunati and Manganelli (1998, pp. 141-149) have produced a three-part

classification, which typifies the use of information and communication

appliances, in a set of European countries. In their rather extensive survey

study three patterns of usage arose; facilitation of

social relationships, management of time, and entertainment. A few years earlier, O’Keefe & Sulanowski

(1995) were able to classify four patterns of phone use in their telephone survey targeted at three US

counties. The patterns identified by O’Keefe and Sulanowski

were similar to those of Fortunati and Manganelli.

They were used for sociability, time management, entertainment and acquisition.

From the perspective of sociological theory, there

is reason to believe that the different patterns of mobile phone usage respond

to the different needs of urban and non-urban life styles. For example, the use

of mobile phones for social relationship facilitation reminds us of

Georg Simmel’s (1962) analysis of urban sociability. Socialising with others is

a kind of necessity in everyday life as one tries to

prevent oneself from feeling the sense of alienation which is a result of the

increased individualization brought about by urban metropolitan life. At the

same time, the urban dweller must also be able to block out a part of the

overflowing sociability of the urban sphere of living, in order to maintain

some privacy. In other words, urban life is about sustaining an adequate level

of privacy amidst overwhelming sociability. Thus, the use of mobile phones for

social relation facilitation could be most beneficial for those who are lacking

social relations and the corporeal proximity of others. This is the case

particularly in non-urban, sparsely populated towns. It is also argued that the urban sphere of life sets

new kind of requirements for temporal coordination. This is because various

everyday tasks (job, home, recreational activities etc.) are spatially and

temporally separated in urbanised societies. The

mobile phone is thus considered as a supplement and substitute to time as a

basis for coordination (Kopomaa, 2000; Townsend, 2002, p. 62; Ling, 2004, pp.

57-81). It combines several

previously separated coordination tools, such as a watch, alarm clock, calendar

and fixed phone. Richard Ling (2004, pp. 61-81) has applied the term ‘micro-coordination’

in this connection. The term is apt as

it describes the increased technological mediation in the arrangements of everyday life

by giving only a limited role to the mobile phone.

The mobile phone use for entertainment can also be linked

with the discourse of urbanity. The urban living-space

is full of stimuli. It contains several competing means and ways to spend free

time, have fun and socialize with other people (Simmel, 1964). It is not only

the mobile phone with a set of content services and mobile games, but also

restaurants, coffee shops, movie theatres, and amusement arcades that try to

persuade young people to have fun and spend time with their friends. The mobile

phone, as a means of entertainment, has to battle against these rivals everyday

in the urban space of living. Therefore, it may well be that the less urban mobile

users take more advantage of the mobile phone as the source of entertainment.

The mobile phone may be used to compensate for the relative lack of urban

entertainments, especially when it comes to the youngest users.

2.2 Determinants

of mobile phone usage

Earlier studies

have pointed out many determinants explaining variation in the ways of using

the mobile phones. Gender is perhaps the most studied aspect of mobile communication

in this respect. These studies indicate that the patterns of mobile phone use

differ to some extent between men and women. Women are more likely to use the mobile

telephone for facilitating social relationships whereas men are more

technology-oriented users (Ling, 2002; Castells et al., 2007, pp. 45-46). Among

the teenagers, boys seem to be more interested in the performance and

applications of the mobile phones whereas the girls are more curious about

design, colours and ring tones (Skog, 2002). There is also some empirical

evidence that women might use the mobile phones to a wider variety of purposes

than men (Puro, 2002). Age seems to

modify the relationship between gender and mobile phones’ usage. In childhood,

differences between girls and boys in mobile phone usage are almost

non-existent (Kangas, 2002; Wilska,

2003). The younger users consider the mobile phone

more as a toy and a game-gadget. The instrumental or functional uses of the mobile

phone increase with age (Castells et al., 2007; Wilska

& Pedrozo, 2007). It is also noted that use for

temporal and spatial coordination increases with the age of young users.

For pre-adolescents, this kind of use is not as essential as it is for older

teenagers whose everyday schedules and social interactions are more complex

(Ling, 2004, p. 100). In addition to age and gender, earlier studies have found

out that the level of education predicts the use of ICTs as well. Education is one

of the most powerful predictors of digital divides within and between counties

(Räsänen, 2006; Wilska & Pedrozo, 2007). 3. Methodology

3.1 Data

The article is

based on quantitative survey data that was gathered through a postal survey in

March-April 2005. The target group consisted of 15-25 year-olds in four Finnish

cities and towns. The cities and towns were grouped into two pairs for the

purpose of analysis. Helsinki and Jyväskylä form the urban pole of the study

whereas Pori and Kuusamo are representatives of non-urban

locations. Although the division is in some respects rough, it is based on

several demographic and socio-cultural factors presented later. The questionnaire

was designed by combining some established question patterns from previous

survey studies with new components specifically framed for this survey. The

established question patterns were mainly adopted from studies carried out by

Statistic Finland (Tilastokeskus, 1999). Some

questions were also selected from the ‘Telecommunication and Society’ survey of

1996 (Fortunati and Manganelli, 1998; Fortunati,

2002). The questionnaires

were posted to 800 people, 200 from each city or town, in May 2005. Respondents

were selected through a random sampling that was carried out by the Population

Register Centre of Finland. The sampling was targeted at native Finnish

speakers only. Reminders were sent to the non-respondents a month later in

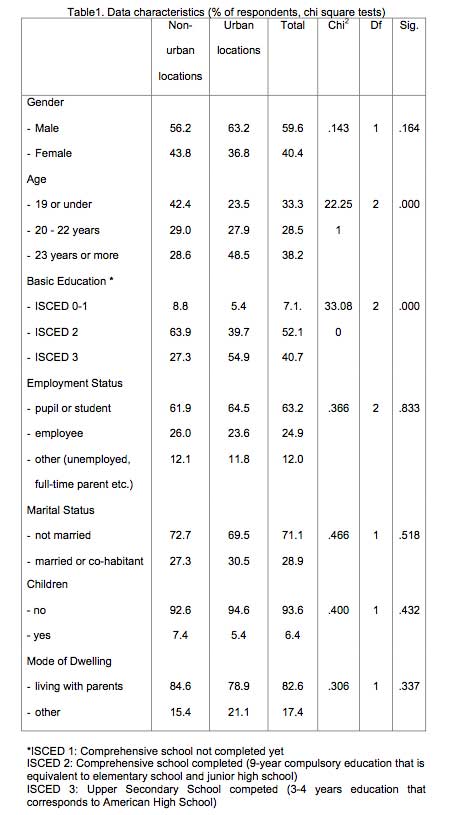

April 2005. The final response rate was 53 % (N=421). Table 1

illustrates the main characteristics of the data, and shows that the data

manifests the young age of the respondents in many ways. The respondent from

the urban and non-urban locations differ from each other mainly by the age and

the basic educational level of the respondents. As young people move to urban

cities to attain further education, it is apparent that the respondent of the

urban cities are also older and more educated. The data is slightly skewed by

gender as well. There are more men than women represented in the data set. In

other respects, the urban and non-urban users register rather similar figures.

More than 60 % of the respondents are pupils or students, more than 70 % are

residing with their parents and less than 20 % have their own children. However,

these structural differences are controlled when analysing the differences and

similarities in the patterns of mobile phone use between the urban and the

non-urban.

3.2 Statistical

methods The study uses a range of statistical methods typical

to the social sciences. Regarding the first research question, the study

applies Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reveal the factors - or more

precisely, principal components - typifying different patterns of mobile phone

use. PCA is extensively understood to be one type of factor analysis, even if these

two differ in terms of their conceptual foundations[i].

PCA like the common factor analysis, can be carried out with different rotation

models to find the most efficient way to group separate variables. In this

study, a

non-orthogonal rotation is used as it permits the inter-correlations of factors

(Tabachnick & Fidell,

2007, pp. 637-638). This is appropriate also in terms of theory as there is no

reason to believe that the different patterns of mobile phone usage would be

mutually exclusive. The study makes use

of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) when tackling the second research question.

One-way ANOVA is the simplest form of variance analysis as it includes only one

independent variable. In this study, all different patterns of mobile phone

usage, derived from PCA, are treated as independent variables one after

another. It is studied whether there is any difference between the urban and

non-urban users regarding the different patterns of mobile phone usage[ii].

As one-way ANOVA is only capable of pinpointing differences

between the groups, another method is needed to tackle the third research question which aims to discover the factors explaining

variation in usages between the urban and the non-urban users. Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA) allows us to control a

set of background variables and to find out which variables modify the relationship

between the patterns of mobile phone usage and the location of use. In MRA,

there is typically one dependent variable and its variation is explained with

two or more independent variables. In this study, the patterns of mobile phone

usage are used as dependent variables, and they are explained with the urbanity

of users and a set of other variables. MRA has also been successfully applied

in other mobile communication studied (e.g. Park, 2005; Miyata, et al., 2007).

MRA allows the controlling of background variables which

irons out many problems related to skewed data. 3.3 Locations

Helsinki and Jyväskylä

are regional growth poles and university cities. They form the urban pole of

the study. Helsinki is the only real metropolitan city of the country with some

560 000 inhabitants. Together with

the other cities of the metropolitan area, they cover a population of

approximately 1 million people. Helsinki is also the most densely populated

(3031 inhabitants/km2) city included in the study (deg. of urbanization

97 %). Jyväskylä is a notably smaller, medium-sized city of around 85 000

inhabitants. The population of Jyväskylä region rises to 150 000 when the

surrounding municipalities are included in the number. The urbanisation rate of

Jyväskylä (98.4 %) is even higher than in Helsinki but its population is not as

condensed (789 inhabitants/km2). Pori and Kuusamo are representatives of non-urban locations as they share

some characteristics of de-industrialisation. Both are located quite far away

from the nearest growth poles. Although Pori’s household and income structure

is quite similar to Jyväskylä, it has suffered from more severe unemployment.

The possibilities for higher education are also much more limited in Pori than

in the two more urbanized cities. People also live more spaciously in Pori (151

inhabitants/km2). Kuusamo is clearly the

most non-urban location of the study and can be classified as a small-town by

its size, services, distances, culture and ways of life (Ojankoski,

1998). It is the least urbanized (61.6 %) and the most sparsely populated (31

inhabitants/km2) of the four research sites. (www.localfinland.fi,

2005). The cities and towns were selected into the survey to represent

geographical and economical diversity of Finnish municipalities. 4. Analysis

4.1 Three patterns

of mobile phone usage The first research

question aims to specify for what are the main patterns of mobile phone usage

among our respondents. The questionnaire included a multiple-choice pattern

that was planned to provide clarification about different ways of mobile phone

use. In this particular pattern, the respondents were asked to assess how often

they use the mobile phone in order to carry out twenty-two different kinds of

tasks (e.g. to keep in touch with your people; to ask and tell news; to gossip;

to play games; to take photos; to listen radio). The respondents were asked to

estimate each item according to the 5-point Likert-scale, where the choices varied from ‘never’ to ‘regularly

everyday’. In general, a

Principal Component Analysis is used to summarise a large number of variables

into a few factors and to decrease the incoherence of the data set. First, all

twenty-two items of the multiple-choice pattern were added to PCA in order to

classify the different patterns of mobile phone usage. From the twenty-two

included items, altogether fourteen received remarkably high factor loadings

and communalities. Only these fourteen items were then included in the

subsequent analysis. In this second phase, principal component extraction with a

non-orthogonal promax-rotation produced the factors with

the greatest utility and interpretability. (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

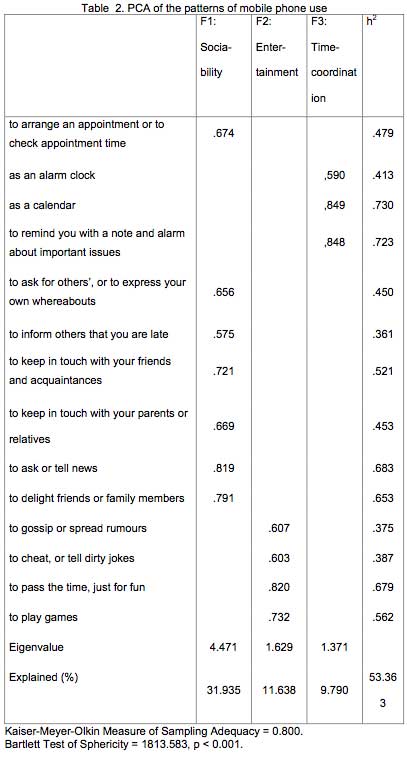

In this case, PCA produced three interpretable factors with eigenvalues greater

than 1.0. The factors and factor loadings are presented in Table 2. The factor loadings smaller than 0.575 were removed from the table

for the sake of clarity. The three factors explained approximately 53 %

of the total variance. The first emerged

factor is termed ‘Sociability’. This factor received high loadings with

statements inquiring if the respondent uses the mobile phone in order to

contact friends and family members, tell news, delight others or inform others

of being late. Moreover a statement about the mobile use for arranging

appointments got a high loading with relation to this factor. Many of these

statements refer directly to mobile-mediated social relationships, while others

refer to arrangements contributing to sociability (e.g. informing others that

you are late). This factor explains approximately 32 % of the total variance.

The factor comes very close to what Fortunati and Manganelli (1998) call ‘the facilitation of social

relationships’. In the

second factor, statements asking about the use for gossiping, cheating, passing

time and playing games through the mobile phone got high loadings. This factor

is named ‘Entertainment’ as all the statements depict a kind of affective use,

instead of functional uses characterized by factors 1 and 3. According to previous

studies, this kind of use is most common to the youngest users (Kasesniemi & Rautiainen,

2002; Thulin & Vilhelmson, 2007). It is

also worth noticing that this factor may partially overlap with the first one. For

example, use for sociability may well include elements of entertainment and

passing time. Nevertheless, this factor alone explains slightly less than 12 %

of the total variance. The

third factor, which is named use for ‘Time-coordination’, is perhaps the most

specified factor in content. It is loaded with statements inquiring about the

use of the mobile as an alarm clock and calendar, as well as to remind the user

himself with a note and alarm about important issues. Other statistical

accounts have also recognized this aspect of use as well (O’Keefe & Sulanowski,

1995; Fortunati and Manganelli,

1998), although it is most vividly discussed in qualitative studies as

part of the concept of micro-coordination. Ling’s (2004,

pp. 57-81) micro-coordination, however, is a much broader concept that refers

to spatial coordination of social activities too. This factor explains slightly

less than 10 % of the total variance within the factor model.

For further

analysis, the three sum variables were composed based on the items loaded on

each factor. To maintain the original 1-5 scales and interpretability, mean

values were used as the basis for sum variables. To ensure the internal

consistency of the new variables, their reliabilities were first

tested by using Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach's alpha is a statistical index that measures how well

a set of variables measure a single underlying

construct. Regarding ‘Sociability’, the alpha was .827

(Mean=3.93, Standard Dev.=.68 , Range=1.00-5.00). The ‘Entertainment’

sum variable reached an alpha value of .667 (M=2.00, SD=.75,

Range=1.00-5.00) and ‘Time-coordination’ got an alpha of .683 (M= 3.63,

SD=1.02, Range=1.00-5.00). 4.2 Differences and similarities in the patterns of mobile phone usage

The second research question of the study is to detect whether the discovered

three patterns of mobile phone usage differ between the urban and non-urban users. An initial comparison between the two

groups is implemented here through analysis of variance. Here one-way ANOVA measures

whether the variance between the urban and the non-urban users is greater than the

variance between them, when use for sociability, entertainment and time-coordination

are used as independent variables one after another. If the variance between

the groups is higher than that of within the groups, it implies that some other

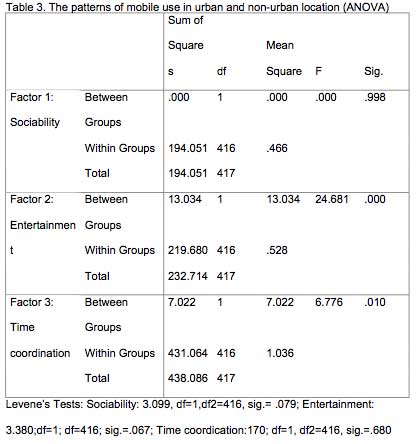

variables might explain the differences. The results of ANOVA are

presented in Table 3. The sig-value for F-test indicates whether the

differences are statistically significant. The table shows no statistically significant

difference between the urban and the non-urban users with regard to the use for

sociability. This is interesting as it could have been

expected that the non-urban users would compensate for the lack of physical

proximity of others with the heavy use of mobiles to foster social

relationships. However, the data does not support this idea. In contrast, young

people in the urban and the less-urban locations seem to utilize the mobile

phones rather equally. Previous

studies have implied that the mobile is not employed so much to maintain

distant relations or establish new ones as it is to keep in touch with close

friends and family members (e.g. Ling, 2004, pp. 111-112). The finding might

indicate that people living in urban and non-urban environments are alike also

in these respects. On the other hand,

ANOVA alludes to the existence of some differences in the use for time-coordination

and entertainment. When analysing these differences more carefully at the level

of mean values, it appears that the respondents of non-urban locations register

higher levels of use for both entertainment and time-coordination. Regarding

the use for time-coordination, the urban users get a mean value 3.49 of and

non-urban 3.75 (range=1-5, F=6.776, sig.=.010).

Regarding the use for entertainment, the mean value for the urban residents is

1.82 and that of non-urbans 2.18 (range=1-5,

F=24.681, sig.=000). As the data is skewed in terms of age, and to a lesser

extent in terms of gender as well, a strong conclusion cannot yet be drawn from

these findings. However, the findings indicate that the users of less-urban

locations have fewer alternative sources of entertainment, and that this lack

may be compensated for by the use of mobile phones for entertainment. This is

explored in the next section.

4.3 Explaining

differences and similarities in the patterns of usage

The third research

question of the study aims to find out what variables explain the differences

and similarities in the use of mobile phones between the urban and the

non-urban users. To explain similarities and differences reliably, a set of background variables have to be controlled. Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA) is an appropriate method for

this kind of research setting. As the gender and age of respondents can be controlled

in MRA, problems related to the skewed variables of the data sets can also be

overcome.

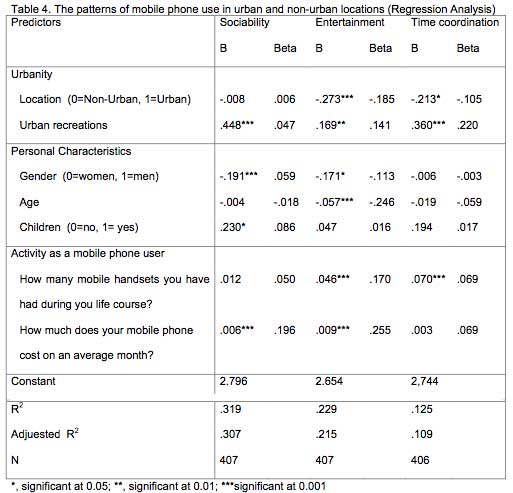

Table 4

illustrates three MRAs, one for each of the dependent

variables that are the three patterns of mobile phone use. The MRAs are carried out with an entered model meaning that all

independent variables are added to the analysis at once. In stepwise or

hierarchical models, on the contrary, independent variables are added one after

another either according to their explanatory capacity or thematical relevance.

The strength of the entered model here is that it makes possible comparisons

between the three parallel models as the order and

composition of independent variables remain the same. The MRA models

presented in Table 4 consist of seven independent variables measuring the level

of urbanity (urban/non-urban location, urban recreations), personal characteristics

(gender, age and children) and respondents’ activity as mobile phone users

(e.g. how many mobile handsets one has owned (M=4.13, sd=2.73,

range=0-20) and how much the mobile costs per month (M=29.98, sd=21.59, range 0-170). The urban recreations variable was

constructed by combining four statements inquiring how frequently people use leisure

time for a set of purposes (e.g. going out to restaurants, pubs and bars;

spending time at cafes, and hanging out with friends). Cronbach’s

alpha for this sum variable was .651 (M= 2.79, SD=.63, Range=1.00-4.00).

Before the presentation of MRAs, it is worth

mentioning that the age of respondents is highly correlated with their level of

education, form of dwelling and current employment status. To avoid collinearity between the dependent variables, only age is

included in MRAs. Correlations between the main

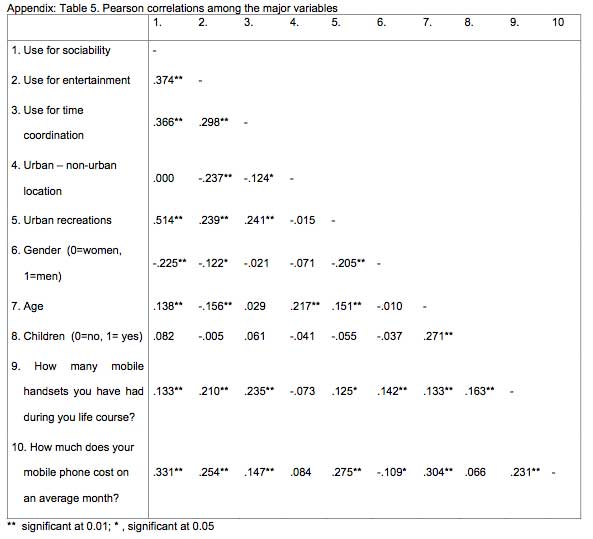

variables are presented in Table 5 (Appendix).

The regression

analysis for the use for sociability confirms that this type of use is not related

to the urbanity of residents’ living environment. This may be related to the

fact that many connections with peoples do not require a physical propinquity

with others (Urry, 2007, p. 47; Ling, 2008). In the non-urban towns young

people may socialise and maintain their social relationships through the mobile

phone, even if others may be physically more distant. In the urban environment

physical contacts with others may be considerably more frequent and varied, but

this as such is not related to the more active mobile phone use for

sociability. Rather, the analysis shows that recreational activities typical to

city life predict the use for sociability considerably. The more people go out

to bars, restaurants and hang out with their friends, the more they use the

mobile phone to facilitate sociability. In other words, the use for sociality

is linked to active and outgoing life styles (e.g. Ling & Haddon, 2001; Madell & Muncer, 2005; Thulin & Vilhelmson, 2007),

which are not directly dependent on the urbanity of one’s living environment. Regarding personal

characteristics, in turn, the analysis shows that women are inclined to use the

mobile phone for sociability more than man. This result has emerged in other

studies as well (Ling, 2002; Castells et al., 2007, 45-46). Having children is

likely to increase this type of mobile phone use as well but the respondent’s

age is not related to the use for sociability. Regarding the respondent’s activity

as a mobile phone user, the analysis shows that there is a positive

interdependence between the costs of the mobile phone and use for sociability.

This model explains 30 % of the total variance of the sociability sum variable.

Regarding the use

for entertainment, the analysis confirms the preliminary findings of ANOVA,

which pointed out some differences between the urban and the non-urban users.

After controlling gender, age, children and the general activity of mobile

phone usage, the non-urban respondents use the mobile phone for entertainment

to a greater extent than those living in the urban environment. Simultaneously,

urban recreations are also predicting this kind of use rather powerfully. The

young age of the respondent - and to a rather limited extent the female gender

- also determine the mobile phone use for entertainment in this data set. It

may also be noticed that the general activity of mobile phone use is also

linked with the use for entertainment. The more frequently the respondent has changed

the handset, the more habitually he also uses the mobile phone to entertain

himself or others. It is almost self-evident that this kind of use is also

reflected in the higher average cost of mobile phone use. This regression model

is capable of ironing out 21 % of total variance of the dependent sum variable. The last

regression analysis attempts to model the mobile phone use for time

coordination. In addition this model confirms the initial findings brought out

by ANOVA and further specifies them. The non-urban users take more advantage of

mobile-mediated time-coordination practices than those living in the bigger

urban cities. Urban recreational activities are powerful predictors of this

type of mobile phone usage as well. This implies that the young people residing

in less-urban areas aspire to spend their free time rather similarly to urban

youth. Furthermore, the analysis points out that use for time-coordination is

common to all kinds of young people: gender, age and children do not explain the

use of the mobile for time-coordination. However, those who change their mobile

handsets often use the mobile telephone, according to this model, more

frequently for the temporal coordination of everyday life. The explanatory

capacity of this model is about 11 % of total variance of the dependent

variable. 5. Discussion and Conclusions This article

addressed the issue of mobile phone usage among young people in Finland.

Respondents living in urban and non-urban locations were compared. The analysis

was based on quantitative survey data and a set of statistical methods. In response

to the first research question, the study was able to identify three patterns

of mobile phone use, namely use for sociability, entertainment and time

coordination. It was also underlined that these data-based

categories are partly overlapping. For example, use for entertainment may

contain various elements of being social with the mobile phone. To answer the

second research question, the study compared the urban and non-urban users in

relation to three patterns of usage. Statistical differences were found

regarding the use for entertainment and time-coordination but not unlike the

use for sociability. It appeared, as it was hypothesised, that the non-urban

users are more active mobile ‘entertainers’ than those living in the urban

environment, replete with alternative sources of amusement. Even more

interestingly, and contrary to what was hypothesised, the study pointed out

that the use for time-coordination activities is also more common among the

non-urban mobile users. In the non-urban locations, the need for temporal

coordination may arise, for instance, from longer physical distances and a lack

of public transportation that forces people to plan their schedules in advance.

However, more empirical evidence is still needed on this phenomenon. The main outcomes

of the study are related to the third research question that aimed to explain

the existing similarities and differences. It was discovered that factors

predicting the various forms of mobile usage differ from one another. Gender,

for instance, predicted the use for sociability and entertainment. Girls were

more likely than boys to use mobiles for entertainment purposes, which may

partially stem from the composition of the sum variable, too. It included only

one question about playing games while others were more ‘social’ and ‘unisex’

by nature (e.g. gossiping, cheating). Age, in turn, was only related to the use

of mobile phones for entertainment, and having children to the use for

sociability. Thus, the study did not give support to the idea that the use for

coordination would become more typical as young persons grow older (Ling & Yttri, 2002; Ling, 2004, p. 100).

The study has

certain limitations which can be viewed as future

research items. The study focused only on four cities and towns in Finland. In

order to further elaborate the findings and generalise them to apply to the

whole population, a more representative survey data would be needed. It may

also be asked whether the identified spatial differences in the use of mobile

phones exist in other countries. Like in mobile communication studies in

general, there is a lack of comparative international studies on spatial

disparities in the use of mobile phones. It is mostly unknown, for instance,

whether there is any location-based differences in the use of mobile phones in

developing countries, and to what extent they are similar to those of developed

countries. Furthermore, it would be of great value to have more in-depth

qualitative information on spatial differences in mobile telecommunication

practices as well. For example, the meanings urban and the rural mobile phone

users attribute to the mobile phone, its mobility and

various patterns of mobile phone usage may vary considerably. This study focused

solely on young mobile phone users. It should be taken into account that

the patterns of mobile phone behaviour and interests among young people differ

significantly from those of the rest of the population. This study showed that

variation within the group of 15-25 year-olds is also noticeable and

measurable. However, the study did not encompass other age groups or

socioeconomic factors, such as the level of education or the socio-economic

status of respondents, which may be associated with spatial differences in the

patterns of mobile phone behaviour. It is apparent that older and more educated

people may not utilize the mobile phones for entertainment purposes as eagerly

as the young users studied. Despite these restrictions,

the study managed to demonstrate that the relationship between the mobile phone

and urbanity is a complex one. As the mobile phone does not presume the

physical proximity of others (Urry, 2007, p. 47; Ling, 2008), it can be used to

facilitate everyday life in multiple manners also in sparsely populated towns.

The spatial complexity of mobile communication should not be taken for granted

and it needs to be studied by empirical methods and from comparative

perspectives as well. References

Campbell, S.W. (2007). A cross-cultural comparison of

perceptions and uses of mobile telephony. New Media

Society, 9, 343-363.

Castells, M., Fernándex-Ardèvol,

M., Qiu, J. L., & Sey,

A. (2007). Mobile communication and society. A global perspective. Cambridge, The MIT Press.

Coogan,

K., & Kangas, S. (2001). Nufix - nuoret ja kommuniaatio-akrobatia:

16-18 vuotiaiden kännykkä- ja internet-kulttuurit (Young people and communication acrobatics:

the mobile phone and internet cultures of 16- to 18-year-olds).

Elisa Research Center report

No. 158. Elisa Communications and Finish Youth Research Network, Helsinki.

Davie, R., Panting, C., & Charlton, T. (2004). Mobile phone

ownership and usage among pre-adolescents. Telematics and Informatics, 21, 359–373.

Fortunati, L. (2002).

Italia: Sterotypes, true and false. In J. Katz

& M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: mobile

communication, private talk, public performance (pp.

170-192). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Fortunati, L., & Manganelli, A. M. (1998).

La comunicazione tecnologica:

comportamenti, opinioni ed emozioni degli

europei. In L. Fortunati (Ed.) Telecomunicando in Europa (pp.

125-194). Milano, Angeli.

Fortunati, L., & Manganelli, A. M. (2002).

Young people and the mobile phone. Revista de Estudios

de Juventud, 57, 59-78.

Green, N. (2002). Outwardly mobile: young

people and mobile technologies. In J. E. Katz (Ed.) Machines that become us:

the social context of personal communication technology (pp. 201-218). New Brunswick & London, Transaction Publishers.

Höflich J., & Rössler, P. (2002). More than JUST a telephone: the mobile

phone and use of the short message service (SMS) by German adolescents: Results

of a pilot study. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 57, 79-99.

Jolliffe, I. T. (2002). Principal component analysis. New York, Springer-Verlag.

Kangas, S. (2002). “Mitä sinunlaisesi tyttö tekee tällaisessa paikassa?” Tytöt ja elektroniset pelit (“What is a girl like you doing in a place like this?” Girls and electronic games). In E. Huhtamo & S.

Kangas (Eds.), Mariosofia. Elektronisten pelien

kulttuuri (pp. 131–152). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Kasesniemi, E-L. (2003). Mobile

messages: young people and a new communication culture. Tampere, Tampere

University Press.

Kasesniemi, E-L., & Rautiainen, P. (2002). Mobile culture of

children and teenagers in Finland. In J. Katz & M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: mobile communication,

private talk, public performance (pp.170-192). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Kopomaa, T. (2000). The city in your pocket: birth of the mobile

information society. Helsinki, Gaudeamus.

Leung, L. & Wei, R. (1999). Who are the mobile phone have-nots? Influences and consequences. New Media & Society, 2, 209-226

Ling, R (2008). New Tech, New Ties: How Mobile Communication Is Reshaping

Social Cohesion. Cambridge, The MIT Press.

Ling, R. & Haddon, L. (2001) Mobile telephony and

the coordination of mobility in everyday life. In J. E. Katz (Ed.) Machines

that become us: The social context of personal communication technology (pp. 245-66).

New Brunswick & London, Transaction Publishers.

Ling, R. (2002). Adolescent girls and young adult men: two sub-culture

of the mobile telephone. Revista de Estudies de Juventud, 52, 33-46.

Ling, R. (2004). The mobile connection: the cell phone’s impact on society.

San Francisco, Morgan Kaufman.

Ling, R., & Yttri, B. (2002) Hyber-coordination via mobile phones in Norway. In J. Katz

& M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: mobile

communication, private talk, public performance (pp.139-169).

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Madell, D. & Muncer, S.

(2005) Are internet and mobile phone communication

complementary activities amongst young people: a study from a ‘rational actor’

perspective. Information, communication, and society, 8,

64-80.

Mäenpää, P. (2001). Mobile communication as a way of urban life. In J. Gronow & A. Warde (Eds.), Ordinary

consumption (pp. 107-123). London, Routledge.

Miyaki, Y. (2006). Keitai use among Japanese

elementary and junior high school students. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, &

M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian. Mobile

phones in Japanese life (pp. 277-299). Cambridge, The MIT Press.

Miyata,

K., Boase, j., Wellman, B., & Ikeda, K. (2007).

The mobile-izing Japanese. Connection to the internet

by PC and webphone in Yamanashi. In M. Ito, D.

Okabe & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian. Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 143-164). Cambridge: The

MIT Press.

Nurmela, J., & Ylitalo, M. (2003). The evolution of the information

society: how information society skills and attitudes have changed in Finland

in 1996-2002. Reviews 2003/4. Helsinki, Statistic Finland.

Nurmela, J., Heinonen, R., Ollila, P., & Virtanen, V. (2000). Matkapuhelin

ja tietokone suomalaisen arjessa (Computers and mobile phones in the everyday

life of Finns). Helsinki, Tilastokeskus.

Nurmela,

J., Melkas, T., Sirkiä, T.,

Ylitalo, M., & Mustonen,

L. (2004). Suomalaisten viestintävalmiudet 2000-luvun vuorovaikutusyhteiskunnassa (Communication skills among the

Finns in the communicative society of the 21st century). Reviews 2004/4.

Helsinki, Statistics Finland.

Nurmela, J., Parjo,

L., & Ylitalo, M. (2003). A great migration to

the information society: patterns of ICT diffusion in Finland in 1996-2002.

Reviews 2003/1. Helsinki, Statistics Finland.

Nurmela,

J., Sirkiä, T., & Muttilainen,

V. (2007). Suomalaiset tietoyhteiskunnassa 2006. (Finnish

people in the information society 2006) Tiede, teknologia ja

yhteiskunta. Katsauksia

2007/1. Tilastokeskus, Helsinki

O’Keefe, G. J., & Sulanowski, B. K.

(2002). More than just talk: Uses, gratifications, and the telephone. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 4, 922-933.

Ojankoski, T. (1998). Oikea pieni kaupunki:

maantieteen ja

asukkaiden näkökulma suomalaiseen pikkukaupunkiin (The

real small town: the Finnish small-towns from the point of view of geography

and small-town residents’). Turun yliopiston julkaisuja

C 142. Turku, University of Turku.

Okada, T. (2006) Youth culture and the shaping of

Japanese Mobile Media. In M. Ito, D. Okabe & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal,

portable, pedestrian. Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp.

41-60). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Oksman,

V., & Rautianen, P. (2002). Perhaps it is a

body part: how the mobile phone became an organic part of the everyday lives of

the Finnish children and teenagers. In J. E. Katz (Ed.) Machines that become

us: The social context of personal communication technology (pp. 293-308). New Brunswick & London, Transaction Publishers.

Park, W. K. (2005) Mobile phone addiction. In R. Ling &

P. E. Pedersen (Eds.) Mobile communication. Re-negotiation of

the social sphere (pp. 253-272). London, Springer-Verlag.

Puro, J. (2002). Finland: a mobile culture. Perpetual

contact: mobile communication, private talk, public

performance (pp. 19-29). Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press.

Räsänen, P. (2006). Consumption disparities in information Society. Comparing

the traditional and digital divides in

Finland. International Journal of Sociology and Social

Policy, 1/2, 48–62.

Rice, R.E & Katz, J.E (2003) Comparing internet

and mobile phone usage: digital divides of usage adoption, and dropouts. Telecommunication policies 27, 597-623.

Simmel, G. (1964). The sociology of Georg Simmel. New York & London, The Free Press.

Skog, B. (2002). Mobiles and the Norwegian teen: identity, gender and

class. In J. Katz & M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual

contact: mobile communication, private talk, public

performance (pp. 255-273). Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Fifth

edition. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Thulin, Eva & Vilhelmson

Bertil (2007). Mobiles everywhere: Youth, the mobile

phone, and changes in everyday practice. Young, 15.

235-253.

Tilastokeskus (1999). Tietoyhteiskuntatutkimuksen

laitelomake 1999 (The questionnaire of information society

research 1999). Helsinki, Tilastokeskus.

Townsend, A. (2002). Mobile Communication in the twenty-first century

city. In B. Brown, N. Green and R. Harper (Eds.) Wireless world: social and

interactional aspects of the mobile age (pp. 62-77). London, Springer-Verlag.

Urry, J.

(2007). Mobilities. Cambridge,

Polity.

Widaman, K. F. (1993). Common factor analysis versus principal

component analysis: Differential bias in representing model parameters. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 28, 263-311.

Wilska, T.-A. (2003). Mobile phone use as part of young

people’s consumption styles Journal of Consumer

Policy, 26, 441–463.

Wilska, T-A, & Pedrozo,

S. (2007). New technology and young people's consumer identities: A comparative

study between Finland and Brazil. Young 15; 343–368.

www.localfinlad.fi (2005). Population and Area, Statistics by municipalities. Retrieved

September 1, 2006 from http://www.kunnat.net/k_peruslistasivu.asp?path=1;161;279;280;43252;43270

Yoon, K. (2003). Retraditionalising the mobile.

Young people’s sociability and mobile phones use in Seoul, South Korea. European Journal Cultural Studies, 3, 327-343.

Author's Note This study

was sponsored by the HPY Research Foundation, Helsinki, Finland.

[i] Whereas in Factor Analysis factors are thought to

cause variables, in PCA variables are taught to cause components (Jolliffe, 2002, pp. 150-151; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007, pp. 611-612). Both aim to reduce the dimensionality of a data set, and are used to

identify new meaningful underlying variables (cf. Widaman,

1993; Jolliffe, 2002). [ii] If variance between these two groups is greater than variance within the groups, ANOVA signifies that there might be some difference between the urban and non-urban ways of using the mobile phone (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007, pp. 195-199). |

||