|

Performing Art History’s Problems with New Media:

Catherine Wilkins (bio)

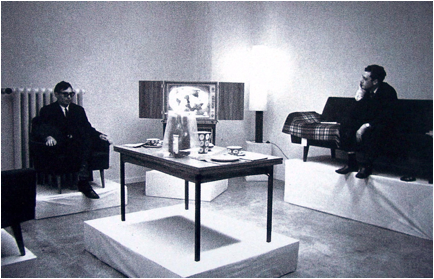

In October,

1963, Gerhard Richter staged a

one-night-only performative installation artwork in the West German city of Düsseldorf,

entitled Life with Pop: A Demonstration for

Capitalist Realism (Figure 1). Appropriating stylistic and thematic conventions of Northern Renaissance

painting, Richter explored the relevance of fifteenth century artistic use of

interior space, object symbolism, and subject-audience interaction to

critically comment upon the benefits and complications of contemporary

interaction between art, politics, and popular consumption. Although the performative installation

possesses pride of place within Richter’s entire oeuvre – it, and the artistic actions of the previous year

that lead up to it, mark the starting point for the artist’s self-constructed career

chronology – Life with Pop has received almost no critical attention from the myriad art historians who

take Richter as a favorite subject. The reluctance of art historians to engage with Richter’s performance

art suggests that performance and installation, though by no means the newest

of “new media,” are still considered

outside of the canon of traditional art and, therefore, not given the same

serious analysis as artworks created using more traditional media. Using Richter’s Life with Pop as an example, this article will examine the strained

relationship between art historians and so-called “new media” art, asserting

that a failure among art historians to critically examine such works can not

only lead to their marginalization, but also to their simplification and

misinterpretation, by scholars and the public alike. Conversely, an openness to the inclusion of art history on

the part of artists, critics, and viewers can add rich layers of meaning to new

media artworks, which can help express artistic intent and address contemporary

context.

In 2005, Gerhard Richter was

identified as the world’s most highly compensated artist,

[1]

a distinction that demarcated him as a figure particularly well-qualified

to address the interaction between creative production and consumer capitalism,

as well as increased his already exceptional international reputation. Richter’s high public profile has made

him a favorite subject for contemporary art historians, particularly when

considered in conjunction with his projected persona, which scholar Peter

Chametzsky describes as that of a “subtle and circumspect thinker…a

conscientious craftsman [who works] in a traditional art form.”

[2]

Indeed, many art historians have

perhaps chosen to study Richter’s work precisely because of this “traditionalism”

that Chametzsky claims for the artist: embracing the use of a familiar medium

(painting, Richter’s most frequent form of communication, being perhaps

something of a rarity in the postmodern period) as well as content. Indeed, scholars have written

extensively about the artist’s “willing[ness] to

engage with almost any [art historical] discourse,” as expressed through their

identification of visual “quotations” in Richter’s oeuvre.

[3]

For example, in a 1996

review for Art Journal, Tom

McDonough called Richter’s career “a reflection on the history of painting.”

[4]

Similarly, in an essay entitled “Appropriations:

Gerhard Richter’s Visual Repertoire,” Julia

Gelshorn examined Richter’s self-compiled catalogue raisonné - entitled Atlas

- and concluded that “the pictures are not his original inventions, but all are

based on other images.”

[5]

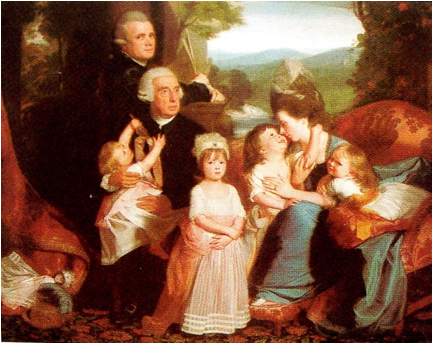

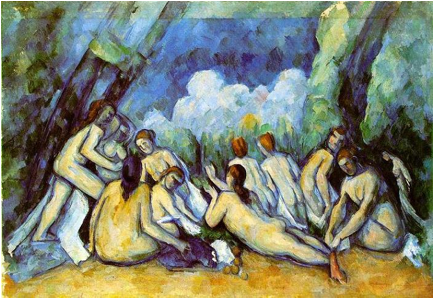

Gelsborn went on to identify several of

Richter’s appropriations, citing the artist’s Family After an Old Master (Figure 2) and Bathers (Figure 3) as examples, these borrowing from John Singleton

Copley’s The Copley Family (Figure 4)

and Paul Cezanne’s The Bathers (Figure

5), respectively. According to

Gelsborn, the purpose of Richter’s “borrowings” is to illuminate the sociocultural

contexts within which art is made and viewed, and the ways in which the passage

of time can affect content and interpretation.

[6]

Further, “this approach allows [Richter’s]

heterogeneous work to reveal qualities, connotations, and ideologies between

high and low art, and between abstract and figurative painting, as well as

between painting and the so-called ‘new media.’”

[7]

Yet not Julia Gelsborn, nor

any other of the art historians who, like her, have sought out the roots of

Richter’s artistic appropriations, have subjected the one example of the artist’s

use of “so-called ‘new media’” to a similar sort of art historical

analysis. Although Richter’s

performative installation piece Life with

Pop was executed in the same decade as the paintings Bathers and Family After an

Old Master, described above, it is often treated ahistorically, as an

anomaly in the oeuvre of the artist.

However, several indicators suggest the importance of Life with Pop to Richter’s body of work as a whole. At the time of the project’s inception,

in 1963, Richter had already been painting for years, and had completed several

major commissions for the East German state, as well as an extensive series of

abstract expressionist paintings, which had won the artist a gallery show in

Fulda after his immigration to the FRG in 1961. Yet the artist, both in word and in deed, has actively

distanced himself from this “early” work, resisting the restoration of his Dresden murals (which had been painted over

several years after their completion), physically destroying the abstract

canvases in an intentional fire and claiming, through his authorized website,

that he “officially began” his career in 1962. In that year, Richter completed a series of paintings in a

style he called Capitalist Realism,

which would become the basis for – and would be included in – his

performative installation work of a similar name a few months in the future.

On October 11, 1963, Richter

and his associate Konrad Lueg

staged Life with Pop: A Demonstration for

Capitalist Realism in a functioning furniture store in Düsseldorf. Leaving in place most of the furniture

that had been installed as sales displays in seventy-eight mock living rooms,

fifty-two bedrooms, and several kitchens and nurseries, the artists added

supplemental symbolic accoutrements,

contributing additional layers of meaning and creating a truly original

installation in the unconventional space.

In the first area that visitors encountered, thirty-nine chairs ringed

the room, each equipped with a copy of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung – a conservative, daily business journal - while on the walls hung

fourteen pairs of deer antlers, earned during hunts executed in the late 1930s

and early 1940s by members of the artists’ families.

[8]

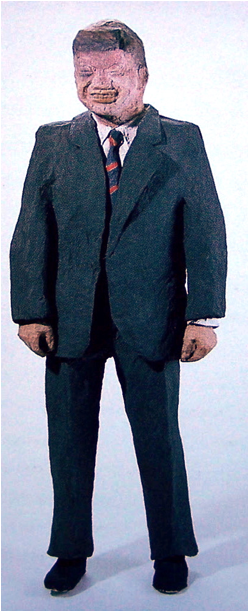

Also in the room were two

life-sized papier mache

figures: one representing President John F. Kennedy, Jr., and the other, the

gallery director Alfred

Schmela (Figure 6).

The next display was the

most openly performative in the installation, as it contained the artists

themselves. Dressed in suits and

ties, Richter and Lueg sat rigidly for an hour and a half in a sleek, modern living

room. A television in a corner, at

which both men directed their gaze, broadcast a special program on the

just-ended “Adenauer

Age.” Between the artists was

a coffee table, topped with table settings and beer bottles wrapped in

plastic. Neither artist engaged

with each other or with the viewer: both, like the television, were the passive

receptacles of the observer’s gaze.

Elsewhere throughout the exhibition space, the artists had installed

several of their own two-dimensional artworks (drawings and paintings), a “costume”

and sculpture made by Joseph Beuys,

interior design magazines, several bottles, glasses, and cups, and the collected

works of Winston

Churchill. Music and liquor,

provided by the artists, encouraged the viewer to interact with the space, to

view themselves as active and complicit participants in a study of the very

political interaction between art and capitalism.

If Life with Pop was so integral to the inception of Richter’s career

that, years later, the artist looked back upon his oeuvre and chose the “capitalist realist” work of the early 1960s as

the moment of his birth as a “true” artist, why is the action so often

overlooked – or, more accurately, given nothing more than a cursory

reference – in Richter scholarship?

For example, in a recent survey of a Research-One University library’s

collection, the vast majority of holdings related to Richter – 12 out of

15 – completely failed to cite the artist’s early performative

installation work.

[9]

A three-volume set published by the

West German government and considered a touchstone resource on Richter’s work

only mentions Life with Pop in the

index of the artist’s exhibitions found in the back of the third book.

[10]

Only one article that references Life with Pop has been published in an

academic journal: Jeremy

Strick’s page-long explication of one of Richter’s two-dimensional artworks

that hung in the installation.

[11]

The most extensive coverage of Life with Pop can be found in Robert Storr’s massive catalogue Gerhard

Richter: Forty Years of Painting, often considered the most

comprehensive Richter reference.

There, the performative installation is examined over the course of just

four paragraphs (half of which are occupied with questions of American Pop Art

precedent) in a source more than three hundred pages long. Storr concludes that Life with Pop was merely a

depoliticized, satirical gesture:

[12]

a claim

that this article asserts is a misapprehension of the work that, in conjunction

with the reluctance on the part of many art historians to engage with Life with Pop, reflects widespread

difficulties in the critical analysis of new media in general.

Certainly, the advent of

so-called “new media” – including performance, installation, video,

digital, virtual, and computer-based art – has presented particular

challenges to scholars that paintings, sculpture, and photography generally don’t. These “new media” and their method of

presentation are often transient, difficult to display and reproduce, or

impossible to financially market in a traditional manner.

[13]

These artworks can be either so limited

(for example, in the case of live performance artworks) or too broad in terms

of their initial audience (such is sometimes the case with Net Art) for

scholars to quantify their general reception, despite the fact that audience

interaction is often central to the agenda of artists creating with “new media.” These factors challenge art historians

to develop new approaches for analysis, and many simply avoid these

difficulties by avoiding a critical study of artworks that employ “new media.”

On the contrary, many new media artists actually embrace these conflicts –

between the media they use and more traditional means of viewing, consuming,

and analyzing art - as integral aspects of their work, rendering transparent

the way these issues have impacted art and art history in the past and present.

[14]

An example of this tendency is Life with Pop, which illuminates the

historic and contemporary intersection of politics, capitalist consumerism, and

art, making this connection more legible and readily understandable to the

viewer through a manner of presentation based on Northern Renaissance

precedents.

With the foundations of

contemporary capitalism established across Northern Europe in the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries, the period and place seem a natural point of reference for

Gerhard Richter’s appropriations on the subject of “Capitalist Realism.” During

this time, Europe became modernized in most all senses, including socially,

economically, and culturally.

Better methods of transport led to massive increases in trade, empire,

resources, and urbanization. These

factors led to a significant shift in the distribution of wealth, as the

flourishing of commerce elevated the social and material status of merchants,

bankers, and those involved in the service industry, giving rise to a modern

class-based economic system.

Proportionately, Northern Europe – in particular, the Low

Countries - financially benefited much more than any other area of the

continent during the Renaissance.

[15]

On a visit to Antwerp in 1520,

the renowned German printmaker Albrecht Dürer noted the

socioeconomic diversity of the urban environment, commenting upon his

interaction with “workmen of all kinds, and many craftsmen and dealers…shopkeepers and merchants…horsemen and foot-soldiers…Lords

Magistrates…clergy, scholars, and treasurers.”

[16]

Among these various strata of the

population, the new influx of material wealth was readily apparent, with

Northern European cities becoming notorious for enabling every conceivable type

of consumption, from “business [to] bourse…breweries [to] brothels.”

[17]

In addition to transforming

the socioeconomic landscape of Northern European society during the

Renaissance, the growth of capitalism also altered culture, giving rise to a

new type of patronage that changed the audience and function of art, along with

the role of the artist. In her

recent book entitled Worldly

Goods, historian Lisa Jardine

explains how the economic wealth, philosophical humanism, and class competition

that characterized Northern European life during the Renaissance led to the

development of the concept of magnificentia.

[18]

Magnificentia

was basically a justification of competitive and conspicuous consumption

cultivated by those who held (or aspired to hold) social status. According to the theory, the patronage

of art and scholarship was a magnanimous pursuit, and could evidence virtue and

intelligence as well as it could display wealth, status, and taste. Just as the conditions of postmodernity

enabled artists such as Richter, in the late-twentieth century, to conceive of

themselves as enacting a “broader cultural role” as a “constructor” of image

and ideology,

[19]

in the

mid-fifteenth century the concept of magnificentia elevated to the status held by independent scholars the professions of painter, sculptor, and

printmaker – previously, strictly controlled via guild membership and

considered crafts on par with that of a carpenter.

[20]

By the sixteenth century, artists began

inserting into paintings representations of themselves engaged in the act of

creative production, creating what Victor Stoichita has

termed the “self-aware

image” to seek answers related to the changing role of art and artists in

an increasingly capitalistic society.

[21]

In so doing, “self-aware images” such

as Dirk

Jacobsz’s Portrait of the Artist’s

Parents (Figure 7) illustrated the enhanced perception of the creative

profession, as well as demonstrate a newfound autonomy in the subject and style

of art-making similar to that with which new media artists experimented four centuries

later.

The self-portrait of the

distinguished artist was but one of the many innovative types of images that

were developed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to meet the needs and

desires of the period’s new middle-class patron seeking to reflect his

intelligence, taste, social status, and contemporaneity. Realism became the most highly prized

aesthetic quality in art, not only because of its links to classical humanism,

which was experiencing a revival particularly in Southern Europe, but also

because of its ability, in art, to create an environment familiar to the

viewer, prompting an identification that would enrich the picture’s theme or

narrative. The accurate perspectival depiction of interior space was one of the

greatest accomplishments of the Renaissance era, as well as a function of the

changing relationship between artist, artwork, and viewer. With their realistic representations of

contemporary Northern European interiors, tableau scenes such as Jan van Eyck’s

famous Arnolfini Wedding Portrait

(Figure 8) lent credibility to the event or idea being depicted, as well as

prompt viewer identification and involvement with the scene, while highlighting

the increasing interest in the secular realm. This tendency was visible even in religious vignettes, such

as Rogier

van der Weyden’s Annunciation

(Figure 9), which, though Biblical in theme, features a very popular fifteenth

century style of bed and bench.

[22]

Art historians such as Eric

Gombrich, Rudolf

Arnheim, and Victor

Stoichita

[23]

have all

argued that, by permitting the transcription of daily, bourgeois living onto

the canvas in symbolic and visual ways never before possible, realistic

interior spaces demanded that the audience engage with the work of art

experientially and conceptually.

This fifteenth century

interest in the use of new artistic techniques to create works that fully

engaged with the observer, encouraging multivalent responses that developed new

states of consciousness

[24]

is

remarkably like the goal of many new media artists of the mid-twentieth century

onward. The Fluxus group, with which Richer was

associated, pioneered the development of performance and installation art as “new

media:” forms of artistic production that sought to “link everyday objects and

events and art” in a manner that was accessible to all of the audience’s senses

via an integration of word, image, sound, and physicality into each artwork.

[25]

In Life

with Pop, the medium of performative installation allowed Richter to

recreate a modified, modernized Northern Renaissance tableau in three

dimensions, pushing the degree of viewer involvement and identification in and

with the scene to new heights.

Whereas many of the artist’s contemporaries, such as Vito Acconci, Dennis Oppenheim, and Terry Fox, were creating performance or

installation artworks in traditional gallery spaces (or, less conventionally,

in outdoor forums), Richter chose a department store as the site of his Life with Pop, relying, much like

Northern Renaissance painters, on the connotations of space and object

symbolism as vehicles for ideological conveyance. In this environment were

conflated, for one night, realms usually perceived of as quite distinct from

one another: a place of commerce, an arena for art consumption, a bourgeois

living environment, and a site of political discourse. By uniting them all in a single place

that was imbued with the symbolism of the sixteenth century, Richter encouraged

artist and viewer to confront the ways in which creativity and capitalism

overlapped with politics and power in both the past and the present, providing

a meditation on the positive and negative ramifications of art’s sociopolitical

value and influence not so different from the Northern Renaissance’s first

fully secular political commentaries.

[26]

The environment created for Life with Pop is similar to that used in

Petrus

Christus’ Goldsmith in His Studio

(Figure 10), a painting that highlights the complicit interaction between

artist and viewer, craftsman and consumer, in the development of modern

capitalism. Often called the first

fully secular image in Netherlandish art, the painting depicts a middle-class

craftsman in his “natural” environs - his workshop - surrounded by the

accoutrements and products of his trade, including jewelry, tableware, and

scales. Commissioned by a

goldsmiths’ guild as a “glorification” of their trade, the interior space and

the objects contained within, as depicted in Goldsmith in His Studio, are

like the books, flatware, and furniture of Richter’s Life with Pop, in that they signify the contemporeneity and

bourgeois nature of the environment.

The symbolic environment is

a reflection upon the inhabitants of both artworks, who

also are critically important in deconstructing the relationship between art

and capitalism in Christus and Richter’s works. The former’s metalworker sits

among merchandise for sale, its beauty and fine craftsmanship providing a

temptation to the consumer-observer, personified by a young, well-dressed

couple that share his space and seem prepared to make a purchase. Although the sight lines of these

characters are all directed at one another, a mirror in the lower left corner

of the picture plane is turned outward, reflecting contemporary figures in a

street scene, meant to represent and prompt identification with the painting’s

observer, who becomes a complicit witness and participant to the capitalist

exchange occurring in the painting’s interior space.

The arrangement of “figures”

within Life with Pop similarly

implicates the viewer in the processes of art’s commercialization. Just as the Christus’ craftsman is

depicted in the midst of his creative production, Richter and Lueg, too, were

actively making art, in the form of their performance. On display, the two men, dressed in

suits that imply the business-like function of the modern-day artist, made

themselves available to the gaze of the viewer, who was filed past the two open

sides of the installation as a means of observation. By symbolically directing

their gazes away from the viewers and toward a television set broadcasting

reports on the very free market-focused Adenauer administration, Lueg and

Richter exposed the co-opting of a potentially creative medium –

television - for the purposes of capitalist propaganda as a form of

contemporary consumption in which artists and viewers alike are complicit. The

commonplace and the commercial aspects of artistic production were thus

emphasized in the twentieth century perfomative installation, just as they were

in the fifteenth century painting, revealing in each artwork the links between

artist and viewer that demarcate both as important cogs in the mechanism of

capitalist consumption.

While the symbolic

environment of Life with Pop sets the

stage and establishes the characters for a discourse on the relationship

between art and its popular consumption, the physical contents of the

performative installation, when considered in an art historical light, help the

viewer reach an understanding of Richter’s complicated and nuanced statement

regarding the function and value of contemporary art’s consumption. The artist’s deliberate placement of

objects charged with meaning in Life with

Pop is reminiscent of a Northern Renaissance artistic device commonly known

as “disguised

symbolism.” As first described by Erwin Panofsky

in 1953, disguised symbolism was a complex visual system that was,

nevertheless, understood by a wide audience, wherein everyday objects were

assigned a symbolic value, in a sort of visual shorthand for lengthier literary

and historical concepts and narratives.

[27]

Scholars of Northern Renaissance art

have argued that the preeminent artists of the period used symbolism in their

depictions of both religious and genre scenes as a strategy for communication

with their audience; a vehicle to “create an experience of revelation”

[28]

through the accoutrements and, thus, the terms, of the material world.

[29]

With this creative strategy in

mind, it is possible to analyze the contents and arrangement of Life with Pop as generating a highly

emotive, political, and moralizing “experience of revelation.” This interpretation exposes the potent

value of Life with Pop, as an artwork

that uses images and themes of popular consumption as a way of making political

statements, rather than an ahistorical, tongue-in-cheek critique of mass

culture, as scholars such as Robert Storr have suggested.

The disguised symbolism that

Richter employed in Life with Pop

seems strongly rooted in the vanitas theme: a particularly popular trope

in Northern European painting during the sixteenth century. Emerging out of the social upheaval and

religious struggles of the period, vanitas

images were moralizing meditations on the transience of life and its material

pleasures, as expressed through a variety of symbolic objects such as glasses

and bubbles (signifying transparency and reflection), flowers and food

(representing the transience of material beings), and timepieces and maps

(suggesting temporality).

[30]

The spiritualized secularism of the vanitas theme can be identified both in

still life paintings, as well as in genre scenes, such as Quentin

Massys’ Money Changer and His Wife

(Figure 11). This early sixteenth

century painting served as a criticism of contemporary societal values that

seemed to be shifting, to favor capitalist materialism over spiritual

devotion. This trend is

personified in the image’s title characters, who look away from the Christian Book of Hours and focus,

instead, on the riches of the world, as represented by the gold coins and stack

of pearls on the table. The disguised symbolism in the painting warns against

such behavior, with an extinguished candle and a withering apple reminding the

viewer of life’s brevity. The open

and empty vessel on the table implies the separation of body and soul after

death, while the money changer’s scale ominously hints of final judgment. Meanwhile, multiple reflective surfaces

– such as the vial and baubles on the back shelves, the ornate cup on the

table, and the convex mirror, which contains an image of an elderly man -

encourage reflection on the part of the viewer, who is meant to see the

transparency, fragility, and concision of her own life mirrored in the Money Changer and His Wife.

As in the vanitas paintings of the Northern

Renaissance, Gerhard Richter’s deliberate use of space and objects in Life with Pop creates an unsettlingly

realistic yet highly evocative environment within which the viewer is forced to

enter and meditate upon the connections between art, politics, consumption, and

death, as symbolized through an arrangement of objects that would be highly

connotative to the contemporary viewer.

The first area that visitors encountered when entering the performative

installation set a potent, politically and emotionally charged, tone of Life with Pop through its allusions to

war and death. In a Northern

Renaissance system of iconography, the stag represented freedom and

independence, because of the animal’s ability to scale great heights and

singularly inhabit difficult terrain.

[31]

The multiple sets of antlers on the

wall of Life with Pop’s so-called “Waiting

Room” suggest the death – or, more accurately, the murder – of such

freedom. By insisting that the

antlers came from deer shot between 1938 and 1942, Richter implies that National

Socialism, the governing power in Germany during those years, whose shadow

still hung so heavily over the nation, was responsible for the

execution. This interpretation is

supplemented by the symbolism inherent in the number of chairs that ring the

room: 39, perhaps an allusion to 1939, the year in which World War II

began.

The placement of the daily

newspaper, the Frankfurter Allgemeine,

in otherwise empty chairs also seems significant. It is as though the seats are being held for persons who are

missing: perhaps the victims of the Nazi regime. That the people who should be sitting in the chairs have

been replaced with copies of a conservative, economically-oriented periodical,

perhaps suggesting the complicity of such interests in the “disappearance” of

the chairs’ inhabitants and, thus, linking political despotism and financial

capitalism. Finally, the room’s papier mache representation of the

gallerist Schmela inserts the art trade into the equation, with his positioning

next to the Kennedy figure suggesting the links between politics and the

business of art, which certainly were manifested during war-time, via

propaganda, and, which Richter suggests, continued into the present decade.

The ideological issues and

concerns conveyed in the “Waiting Room” were carried out in a more subtle

fashion in Life with Pop’s main room,

which borrowed object symbolism more directly from the Northern Renaissance

trope of vanitas painting. On the coffee table in the main room

were two place settings, with dessert and drinks half-consumed: a decadent

feast, representing a decadent life, abruptly interrupted. Three bottles of alcohol, symbolizing

another material temptation, sat atop the table encased in plastic, as though

the artists were attempting to preserve the passing pleasures of physical

consumption. Flowers,

beginning to wilt, lay upon a nearby tea table, while an empty vase – a

Northern Renaissance pictorial convention alluding to the soul’s separation

from the body in death, represented by the empty shell of the vacant vessel

[32]

- was also at hand. The inclusion

of secular texts in Life with Pop

(most notably, the collected works of Winston Churchill) is also an

appropriation of a vanitas motif by

which products of humanistic learning are held up as examples of man’s hubris, symbols of earthly knowledge

that pale and pass away in the face of eternal spiritual truths.

[33]

The books’ political nature

additionally helps reinforce the symbolic, symbiotic relationship between

cultural production and death; war, politics, art, and popular consumption

suggested by the disguised symbolism found elsewhere in Richter’s performative

installation.

When viewed in conjunction

with one another, Richter’s various references to and appropriations of art

history – particularly those pertaining to Northern Renaissance artistic

conventions and sociocultural contexts - enhance our understanding of the

artist’s intention in creating Life with

Pop. As in the “self-aware

images” of the sixteenth century, the artist-populated performative

installation probed to find the purpose of the craftsman and, in so doing,

illuminated art’s potential value and power, not only as an object for

consumption, but also as a producer of a message or idea capable of being

consumed. Richter’s use of

disguised symbolism and the vanitas

theme suggested both the benefits and drawbacks to the co-opting of art by

politics and the media by demonstrating that culture was capable of promoting

violence and death yet could also provide a moral voice through which

contemporary values or events could be challenged. By both physically and

symbolically including the audience in Life

with Pop, Richter also gave the viewer an opportunity to meditate on her

role in the dynamic between art, politics, power, and consumerism for

reflection, showing the observer that she, too, is part of the answer regarding

the present purpose and value of art.

This reading of Richter’s

work suggests that more traditionally-oriented art

historians and the theoretical approaches they favor are relevant and

meaningful, even when applied to studies of new media art in general. As mentioned briefly above, art

historians have too frequently been wary of new media, and stymied by what one

scholar has called the “overwhelming and often irrelevant meaning that

comes from the peculiarity of the medium.”

[34]

While Richter’s performative

installation may indeed seem “peculiar” at first - particularly when considered

a part of his otherwise quite painterly oeuvre – an analysis of Life With Pop

that focuses on iconography and sociocultural context shows the traditional art

historian that there can be found something familiar in “new media,” capable of

being critiqued through conventional means. Certainly, new technologies and forms of production,

reception, and interaction do call out for a language of discourse that is

capable of interpreting and conveying the particularities of each medium: art

historians must meet practitioners of new media at least halfway by

familiarizing themselves with the rhetoric of the practice. Yet, as the above study of Life with Pop has hopefully shown,

broader art historical methodological approaches are, in and of themselves, not

irrelevant to analyses of “new media.”

This realization is not only

beneficial to the individual art historian, who may gain a greater appreciation

for new media art – and a fresh avenue for research – by embracing

it. An expanded scholarly

treatment of new media art will also enhance the academic discourse surrounding

the field: a cultural landscape recently referred to as “an impoverished ghetto”

by the artist Margaret Benyon.

[35]

The isolation of new media studies

within and outside of art history has tended to exclude “historical and

expressive meanings and rewriting them as matters of physics, neurophysiology,

or personal, ahistorical ‘artistic judgement.’”

[36]

The limited and exclusionary tendencies

of this approach could be reversed through an application of critical, “traditional”

art historical theoretical and methodological paradigms, leading to an increase

in academic publication and more classroom time dedicated to the study of the

subject. Furthermore, a “trickle-down”

effect, whereby better understanding of new media art among the intellectual

elite could impact broader popular interest in the field – might be

expected. Increased attention and

ease in analyzing new media art could only improve communication regarding its

values, functions, and meanings, resulting in better museum texts, methods of

display, and thematic exhibition organization. Historicizing new media may make unfamiliar forms of expression

seem more relevant to the average observer’s understanding of the field and its

relationship to the micro- and macrocosm, while simultaneously expanding

preconceived notions about art-making and art-viewing. Such an enhanced public embrace of new

media art may be possible, facilitated by the concentrated academic attention

of scholars currently avoiding interpretations of the field that connect it to

a longer, art historical tradition.

Just as art historians have

expressed some reluctance to deal with their counterparts on the other side of

the artwork, new media artists, too, have demonstrated some hesitancy to

incorporate art history into their work, as a panel at the 2008 CAA conference entitled “Video Needs Art History Like a TV

Set Needs a Plinth” suggests.

In claiming that, “for art historians, video offers no surface for

inspection (like pictures) nor necessarily any depth for probing (like

writing),”

[37]

the session chair expressed an overly simplified understanding of art history’s

potential approach to its new media subject. Furthermore, this perspective ignores or discredits past

interaction between art history and video art in the “new medium’s” more

primitive forms, such as photography and film.

Such an exclusionary

attitude is also often conveyed by less overt means. For example, the art historian James Elkins claims that entire

monographs and conferences on the subject of virtual reality as art are

published or conducted “without making contact” with the non-technological

sources and language upon which the basic premise - of virtual reality being

considered a form of art – is based.

[38]

Such skepticism toward and

rejection of art history likely reflects the alienation imposed on contemporary

artists by the many old-fashioned practitioners of the discipline who are

unwilling to engage with “new media.”

Yet, in attempting to assert their independence and distance themselves

from the field of art history, new media artists may, in fact, be keeping their

work from broader public exposure, better degrees of understanding among the

public, increased financial success, and possibly even the better fulfillment

of creative potential.

If, as John Hanhardt, director of

New York’s Guggenheim Museum,

asserts, “curatorial museum culture [is] the ultimate validating source”

[39]

for artworks created using new media, then critical discourse about the work of

art is necessary for its ultimate success. Although the very purpose of much new media art has been to

eschew the museum and gallery system, liberating and democratizing the

art-making and viewing processes by taking the artwork to the streets, to the

television airwaves, and to the internet, Hanhardt’s observation is a pointed

one. While new media have allowed

artists to reach their audience outside of traditional, academic circuits, for

the work to be received as art – and received less locally – it

must find a way to insert itself into an appropriate arena of discourse. Additionally, because many artworks

created with new media do not represent a singular, stable object that can be

offered for sale, an individual striving to make artistic production a

full-time career must be able to conceptually market his works to institutions

or individuals invested in the arts and willing to bankroll such

endeavors. In all cases, the

artist’s success is reliant upon the artwork’s ability to comprehensibly

represent itself as art, while simultaneously striking a chord with an

appropriate, educated consumer.

Seemingly, one way in which to achieve this effect would be to relate

the new media production to an art historical tradition – either in

content, form, or theoretical approach.

By familiarizing one’s self with the discipline and rhetoric of art

history, the new media artist can not only enhance the legibility of his art

among an audience that is seeking the meaning and ideology of the work, but he

can also, in a way, legitimate the work by demonstrating an intellectual

awareness of its context, both past and present.

Some new media artists have

found that a conceptual and theoretical embrace of art history has not only

provoked increased levels of understanding on the part of a broader audience,

but has also enhanced the value and resonance of their unique creative visions. Joan Truckenbrod, for example, has

been a prolific proponent of the integration of art history and “new media,” as

a vehicle for more fully expressing her ideas about the complex relationship

between technology and the human experience. Truckenbrod’s early work - interactive installations

involving digitized images and sound – strove to show that intermedia is

the fullest expression of the “natural human condition:” a thesis bolstered by

the artist’s citation of art, music, and performance’s past fusions as

reflections of universal “human sensibilities” seen throughout the history of

art.

[40]

In her interactive computer-based

installations - such as “Torn

Touch” (1997) – Truckenbrod cites the “ancient” social and economic

dimensions of weaving and its more recent art historical implications as a “metaphor

for the construction of social, political, and commercial internet weavings,”

on the World Wide Web.

[41]

This conceptual connection, based on

art historical knowledge, helped the artist to create an artwork wherein the

viewer became the bridge between physical and virtual realms, involving the

audience and art history to solve the dilemma regarding the denial of touch as

a sensory experience in contemporary new media art.

Thus, as Gerhard Richter did

four decades previously, Truckenbrod more recently employed

her familiarity with art historical conventions to address very contemporary

questions about the intersection of life and art, ideology and history,

viewership and consumption. Such a

tactic, employed by artists working in new media, can add layers of import to

cultural production. Yet, for such

a strategy to be fully successful in communicating the significance of subject

matter and/or means of contemporary creative constructs to a viewer, scholars

must be willing to identify and analyze historical precedent in new media

artworks, acknowledging the works and the discourse which surrounds them as legitimate

heirs to an art historical tradition.

Though an examination of Life with

Pop’s relative obscurity within Richter’s oeuvre reveals the unfortunate

divide that often exists between art historians and practitioners of new media

art, the work itself points the way to a resolution of this rift. Through a truly postmodern attitude of

inclusiveness that acknowledges the interplay of history and contemporary

contexts as a response to age-old interrogations of the relationship between

art, politics, and consumption, Life with

Pop illuminates the benefits and relevance of a marriage between new media

and art history, for artists, scholars, and viewers alike.

FIGURE 1: Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg, Life with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist

Realism (performative installation, 1963).

FIGURE 2: Gerhard Richter, Family After an Old Master (oil on canvas, 1965).

FIGURE 3: Gerhard Richter, Bathers (oil on canvas, 1967).

FIGURE 4: John Singleton Copley, The Copley Family (oil on canvas, 1777).

FIGURE 5: Paul Cezanne, The Bathers (oil on canvas, 1906).

FIGURE 6: Gerhard Richter, John F. Kennedy (papier-mache, 1963).

FIGURE 7: Dirk Jacobsz, Portrait of the Artist’s Parent (oil on canvas, 1550).

FIGURE 8: Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Wedding Portrait (tempera on panel, 1434).

FIGURE 9: Rogier van der Weyden, Annunciation (oil on panel, c. 1440).

FIGURE 10: Petrus Christus, Goldsmith in His Studio (oil on panel, 1449).

FIGURE 11: Quentin Massys, Money Changer and His Wife (oil on panel, 1514).

[1] “Deutschland Siegt in der Kunst-WM,” Bild Zeitung, 28 October 2005, 26. [2] Peter Chametzsky, Objects as History in Twentieth-Century German Art: Beckmann to Beuys (In contract: University of California Press), 259. [3] Reinhard Spieler, “Without Color,” in Gerhard Richter: Without Color, ed. Reinhard Spieler (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 17. [4] Tom McDonough, “Review: Gerhard Richter,” Art Journal 55/3 (Autumn 1996): 90. [5] Julia Gelsborn, “Appropriations: Gerhard Richter’s Visual Repertoire,” in Gerhard Richter: Without Color, ed. Reinhard Spieler (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2005), 27. [6] Gelsborn, “Appropriations: Gerhard Richter’s Visual Repertoire,” 29. [7] Gelsborn, “Appropriations: Gerhard Richter’s Visual Repertoire,” 35. [8] In the self-authored catalogue notes from Life with Pop, Richter claimed that the antlers were obtained between 1938 and 1942. Storr, Gerhard Richter: Doubt and Belief in Painting, 49. [9] Survey, Tulane University Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, conducted March 11, 2007. [10] Gerhard Richter, Gerhard Richter (Bonn: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1993). [11] Jeremy Strick, “Mouth (Mund), 1963 by Gerhard Richter,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25/1 (1999): 24-25, 102. [12] Robert Storr, Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 33. [13] Dick Higggins, “Statement on Intermedia,” http://www.artpool.hu/Fluxus/Higgins/intermedia2.html (accessed 18 June, 2009). [14] Many examples of this tendency can be found in the artworks described in: Gregory Muir, “Past, Present, and Future Tense,” Leonardo, 35/5 (2002): 499-500+502-508. [15] In the fifteenth century, the port cities of Bruges and Antwerp had become the largest international centers of trade, outpacing their only southern European rival, Venice, by more than ten times the commercial traffic per year. James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2004): 433. [16] Albrecht Dürer, diary entry, August 4, 1520. Reproduced in W.M. Conway, Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1889), 96ff. [17] Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art, 433. [18] Lisa Jardine, Worldly Goods (London: MacMillan, 1996). [19] Chametzsky, Objects as History in Twentieth-Century German Art, 252, 259. [20] Snyder, Northern Renaissance Art, 416. [21] Victor Stoichita, The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). [22] Barbara Lane, “Sacred vs. Profane in Early Netherlandish Painting,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 18/3 (1988): 108. [23] Eric Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), 242-291. Rudolf Arnheim, The Power of the Center: A Study of Composition in the Visual Arts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 172-208. Viktor Stoichita, L’instauration du tableau. Meta-peinture á l’aube des temps modernes (Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck, 1993). [24] James H. Marrow. “Symbol and Meaning in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Renaissance,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 16/2/3 (1986): 152, 163. [25] Michael Rush, New Media in Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), 24, 53. [26] Several scholars cite the work of Pieter Breugel the Elder as Europe’s first artistic examples of secular political commentary. See Ross H. Frank, “An Interpretation of Land of Cockaigne (1567) by Pieter Breugel the Elder,” Sixteenth Century Journal, 22/2 (Summer 1991), 299-329; Margaret Sullivan, “Breugel’s Proverbs: Art and Audience in the Northern Renaissance,” Art Bulletin, 73/3 (Sept. 1991), 431-466. [27] Erwin Panofsky. Early Netherlandish Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953), esp. 131-148. [28] John Ward, “Disguised Symbolism as Enactive Symbolism,” Artibus et Historiae 15/29 (1994): 12. [29] Lane, “Sacred vs. Profane in Early Netherlandish Painting,” 114. [30] David Petit, “A Historical Overview of Dutch and French Still Life Painting: A Guide for the Classroom,” Art Education 41/5 (Sept. 1988), 14-19. [31] George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 1954), 26. [32] Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, 325. [33] Petit, “A Historical Overview of Dutch and French Still Life Painting,” 18. [34] In this case, the medium in question was computer imaging. James Elkins, “Art History and the Criticism of Computer-Generated Images,” Leonardo 27/4 (1994): 336. [35] Margaret Benyon, “Do We Need an Aesthetics of Holography?” Leonardo 25/5 (1990): 415. [36] Elkins, “Art History and the Criticism of Computer-Generated Images,” 335. [37] Anthony Auerbach, “Abstract: Video Needs Art History Like a TV Set Needs a Plinth,” in Abstracts: CAA 2008 96th Annual Conference (Lancaster: Cadmus/Science Press, 2008), 17. [38] James Elkins, “There Are No Philosophic Problems Raised by Virtual Reality,” Computer Graphics 28/4 (Nov. 1994): 254. [39] Cited in Michael Rush, New Media in Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005), 88. [40] Joan Truckenbrod, “Integrated Creativity: Transcending the Boundaries of Visual Art, Music, and Literature,” Leonardo Music Journal 2/1 (1992): 89-95. [41] Joan Truckenbrod, “’Torn Touch:’ Interactive Installation,” Leonardo 33/4 (2000): 265-266. |

||