|

New Media-Same Stereotypes: An Analysis of Social Media Depictions of President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama

Baylor University Abstract To remain relevant, it is necessary for media scholars to test theories in new media environments. Building on feminist and critical race theory, this textual analysis investigates Facebook photos and pages targeting President Barack and Michelle Obama in 2011-12. Findings indicate Facebook fans build on historical stereotypes and cultural narratives to frame the two negatively. Representations often depict them as evil, animalistic and socially deviant. Study findings demonstrate that historical representations of Blacks are strong and have an impact on modern portrayals. This topic is particularly important today in this age dubbed “post-racial” to depict an era in which U.S. citizens elected the first black president. In addition to identifying the nuances of Facebook hate groups, this study explores historical representations of African Americans, discusses how they transcend to a new media platform and offers implications for future research. To navigate the rapidly changing media climate, students and media scholars must learn how to read and critically dissect Web content. This paper provides a good foundation upon which to build. Introduction Traditionally, hate groups recruited members and spread extremist messages by word of mouth and through the distribution of flyers and pamphlets. In contrast, the Web allows members all over the world to engage in real-time conversations (Meddaugh and Kay, 2009). The growth of Facebook groups from a fringe activity to a significant communication source illustrates the recent evolution in the spread of hate speech. Hate groups, which might have remained benignly isolated at one time, recruit online and increase their numbers instantly. Social networking sites such as Facebook have experienced a huge explosion in numbers of extremists who cultivate their numbers in cyberspace with the greatest increase coming from overseas, particularly Europe and the Middle East (SWC, 2009). The Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC), in its 2009 iReport, identified more than 10,000 problematic hate websites (SWC, 2009). The report includes websites, social networks, blogs, newsgroups, YouTube and other video sites. The findings illustrate that as the Internet continues to develop, extremists find new ways to seek validation for their repulsive agendas and to recruit members (Amster, 2009). Communication histories often concentrate on changes evoked by the arrival of a new medium in the public sphere (Schmidt, 2010). Previous studies have focused on legal and ethical ramifications of hate groups and the First Amendment and (e.g. Henry, 2009; Reed, 2009). Others analyze the online works of a particular group such as the Ku Klux Klan and the Aryan Nation (e.g. McNamee, Peterson & Pena, 2010; Meddaugh & Kay, 2009). However, there is a gap in the critical race literature in the area of social media representations of marginalized groups. This essay fills that void with an analysis of how historical representations of African Americans transcend to Facebook portrayals of President Barack and Michelle Obama in 2011-12. Findings offer solutions and implications for future studies. This analysis is important for several reasons. First, in addition to identifying the nuances of Facebook hate groups, this study explores historical representations of African Americans, discusses how they transcend to a new media platform and offers solutions and implications for mediating online hate speech. Secondly, mass media provide historical content that researchers may use to analyze trends in the perceptions of gender and race. This topic is particularly relevant today in this age dubbed “post-racial” to depict an era in which U.S. citizens elected the first black president. Some critics argue President Barack Obama’s election is evidence of a “post-racial America,” while others believe events following his election have exposed the degree to which racism is still prevalent (Ono, 2009). For instance, Kaiser et al. (2009) and Knowles, Lowery and Schaumberg (2009) concluded Obama’s victory might provide people with a new justification for the claim that racism no longer exists in the U.S.; therefore, policies to address racism are no longer necessary. Similarly, Effron, Cameron and Whites (2009) speculated that expressing support for Obama might license people to favor whites at the expense of African Americans. Both viewpoints illustrate enlightened racism described previously by scholars such as Jhally & Lewis (1992) and Entman (2000). Even with this disagreement, the historical significance of having the first black U.S. president is undeniable. Thirdly, the First Amendment is also a consideration for Facebook groups and pages containing hate speech. Understanding how communities create themselves online provides insight into the effects of new media on more traditional issues of freedom of speech. Although the First Amendment prohibits governments from regulating the content of speech except for cases of defamation and incitement to riot, some philosophers argue for blanket protection of First Amendment rights, while others are not as supportive in cases of sexist or hate-based language (Frankel, 2004; Mill, 1869). Mill (1869) maintained that the First Amendment should not protect ideas, images or words if they are harmful to another individual. Scholars must continue to explore the dynamics of freedom of speech within new media platforms. Lastly, given the tremendous popularity of the Web, some observers predict user generated content (UGC) such as YouTube videos, blogs and other forms of social media may eventually displace traditional broadcast media as the main outlet for news and entertainment (Freeman and Chapman, 2007). Because of the shift in media gatekeeper roles, the potential impact of social media on race and gender discourse is phenomenal. To take advantage of this shift in media, students and media scholars must learn how to read and critically dissect the Internet and other forms of new media. In the process, they may become engaged democratic citizens. This paper provides a good foundation upon which to build. In addition, this extension of hate group literature might raise community awareness and foster sensitivity to race, culture and gender issues, leading to better portrayals of marginalized groups. This study extends the current literature by providing an analysis of the types of Facebook hate groups and suggesting guidelines for identifying and controlling hate within the realm of social media. Such analyses are important because scholars must study new communication methods using traditional “mass media” theories to assess if and how they apply to developing media platforms. Additionally, where stereotypes and hate speech prevail, scholars must also study a medium’s potential to influence the construction of the racialized condition in which we live. It is often through media images that people negotiate identities, ideas, and relationships with other subjects (Ono, 2009). Audiences must possess the knowledge and skills to critically think about the technology and media they use everyday. This paper provides a good foundation upon which to build. Review of the Literature Critical race studies often fall into two categories: race and gender. Using these categories as an outline, this article offers a general overview of stereotypes and explores the intersection of gender and race within Facebook hate groups. Lippmann (1922) defined “stereotype” as a form of perception that imposes ways of seeing others. Members of dominant groups often use stereotypes to dehumanize subjects based on race, values, religion and/or physical characteristics. Stereotypes also help them maintain political power, social control and offer a rationalization for the mistreatment of marginalized groups. Hegemonic processes aim to build a consensus among the masses that indicate a certain ideology is normal (Gramsci, 1997). Gitlin (1980) concluded that those in positions of power do not directly maintain status quo: “The task is left to writers, journalists, producers and teachers, bureaucrats and artists organized within the cultural apparatus as a whole” (p. 254). Economic interests, dominant ideologies, government influences and journalistic norms shape media (Parenti, 1986 & Chomsky and Herman, 1988). Subsequent media studies have concluded that a group’s dominance sustained in media and popular culture is not permanent. Shifts in power are possible; however, constituents must fight for the upper hand (Hall, 1980). New media platforms increase the possibilities for transformations. While communication has traditionally been top-down, the Web opens up the possibility of horizontal communication without the interference of gatekeepers. Consequently, media dynamics have changed considerably. Blackface representations Historical portrayals of African-American men and women often fell into three categories: blackface/animalistic, social deviance and evil/angry. Blackface portrayals overemphasized and ridiculed the facial features, personality traits and diets of African Americans. This genre often included popular stock characters such as “jungle bunny," “Rastus," “Mammy" and “Uncle Tom" (Levinthal and Diawara, 1998). “Uncle Tom," the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is a term for a person who behaved in a subservient manner to whites. On the other hand, “Rastus," popularized in minstrel shows, is a pejorative term in which the black male character was always happy even in less-than-ideal conditions.

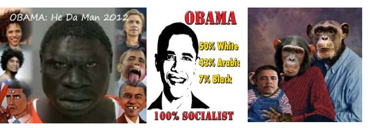

Figure 1. Historical stereotypes of African Americans typically focused on animalistic qualities and blackface humor Conversely, “jungle bunny” or “porch monkey” stereotypes encompass references to laziness, dark skin, nappy hair and animal-like qualities, resembling monkeys or apes. Other common derogatory terms include “tar baby,” “pickaninny” and “jigaboo” all of which have exaggerated facial features such as eyes, noses and teeth, in addition to disproportionately large upper torsos, meant to give the impression that they are half-human and half-animal (Origins of Racist Terms, 2011). Such characters often appeared brute, savage and not particularly smart or essential to society. Also common were images of African Americans eating watermelon, fried chicken and chitterlings (Counihan & Van Esterik, 1997). Also common were images of African Americans eating and drinking certain beverages and cuisine. For example, media often featured Blacks drinking red soda or Kool-Aid and eating watermelon, fried chicken, cornbread, pig’s feet and chitterlings (Counihan & Van Esterik, 1997). During the slave era, these foods were considered undesirable because slaves enjoyed them and/or because they were slave-owners’ “leftovers.” Media imagery of black people eating such items fostered an “us” versus “them” context that was humorous and self-promoting for members of the dominant group. Stigma attached to so-called “soul food” still lingers today. Evil/angry representations Depictions are of concern because negative stereotypes spill over into news media portrayals of minorities. Previous studies have concluded that news stereotypes of people of color are pervasive (e.g. Dates & Barlow, 1993; Martindale, 1990; Collins, 2004; Poindexter, Smith, & Heider, 2003; Rowley, 2003; West, 2001). In general, people of color occupy roles as the underclass, loud politicians and criminals on network news. National media watch group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) points out that in contrast to the media’s overrepresentation of people of color as criminals and druggies is their underrepresentation as experts and analysts (Biagi, 2007). The civil rights era presented some different portrayals. African Americans were often associated with racialized issues such as bussing and segregation—topics that might fuel fear and racial intolerance by Whites. Grimm (2007) explored how the New York Times framed Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., from 1960 through 1965. Both men are icons of contemporary African-American culture and had a great influence on Black Americans. However, Grimm concluded that the main premise of articles covering Malcolm X centered on his diminishment as a leader, public mistrust and skepticism of the leader and Black Muslims, a deep fear of racial violence and the stigmatization of the political icon. Media outlets often labeled Malcolm X a deviant while they embraced King as a righteous leader. Grimm (2007) concluded that such characterizations reinforced hegemonic power structures and supported ideological notions of accepted U.S. racial norms. Similarly, Douglas (1995), who looked at representations of O.J. Simpson, Louis Farrakhan, and the Million Man March, found that media placed African-American men on a spectrum of good versus evil. In the 1980s and 90s, stereotypes of black men shifted and the primary images were of violent criminals, crack cocaine dealers/addicts, underclass and homeless (Drummond, 1990; Entman, 2000). Strudler and Schnurer (2006) found media portrayed black athletes as deviant animals in both their home lives and on the field on ESPN’s show, “Playmakers.” Mirroring Strudler’s findings, Billings (2003) concluded that racism was not evident when golfer Tiger Woods won major tournaments, but when he was not successful media was more likely to criticize him, charactering him as the “typical” black athlete—deviant and self centered. Feminist theory and representations of black women For feminist theorists, there is no dispute that media function ideologically, working with other social and cultural institutions to reflect, reinforce and mediate existing power relations and ideas about how gender is and should be lived (Enriques, 2001). Many feminist studies conclude that media often represent women stereotypically as passive, submissive and dependent (Ferri & Keller, 1986; Van Zoonen, 1996; Carter & Steiner, 2003). Van Zoonen explained that the differences fulfill the structural needs of a patriarchal and capitalist society by reinforcing gender differences and inequalities, while Carter and Steiner (2003) assert that sexist images reproduced by the media make hierarchical and distorted sex-role stereotypes appear normal. Early feminist theory emphasized the commonalities of women’s oppression. However, black feminists argued one could not conceive of black women’s experience of various issues as separable from their experience of racism. Take sexism, for instance: women of color do not experience sexism in addition to racism, but sexism in the context of racism. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that while media are unjust to both black and white women, they stereotype and denigrate black women to a greater extent (e.g. Benedict, 1997; hooks, 1992; Squires, 2007; Schell, 1999). Dichotomous representations depict black women as either oversexed or asexual, unintelligent or extremely educated, ambitious or listless, attractive or unattractive (e.g. Boylorn, 2008; Collins, 2004; Entman & Rojecki, 2000 and hooks, 1992). For instance, the sexually promiscuous black woman, also known as the “oversexed-black-Jezebel,” is an extreme opposite of the “mammy.” Similarly, the “welfare cheat,” who lives lavishly off public assistance, is the opposite of the overachieving, “independent black woman” who is overachieving and financially successful on one hand; and narcissistic and overbearing on the other. One of the most popular stereotypes of African-American women is that of the “angry black woman” who media depict as upset and irate (Collins, 2004, p. 123; Childs, 2005, Springer, 2007). Collins (2004) identified class-based controlling images of Black women that range from “bitches” and bad (black) mothers to modern mammies. ‘‘The controlling image of the ‘bitch constitutes one representation that depicts Black women as aggressive, loud, rude, and pushy’’ Collins stated (2004, p. 123). The angry black woman stereotype is a spinoff of Sapphire, a historical character who berates black males in their lives with cruel words and exaggerated body language. Media often show the wisecracking, emasculating woman with her hands on her hips and her head thrown back as she lets everyone know she is in charge (Yarborough & Bennett, 2000). There is also a growing body of research regarding the stereotyping of black, female athletes. Such studies focus on how media outlets frame them as both racially and sexually different/deviant. Depictions often imply they do not meet white mainstream standards of beauty and are defeminized. Scholars have also concluded U.S. sports media often give women of color considerably less coverage than they give their white female counterparts (Blinde and McCallister, 1999; Maas and Holbrook, 2001).

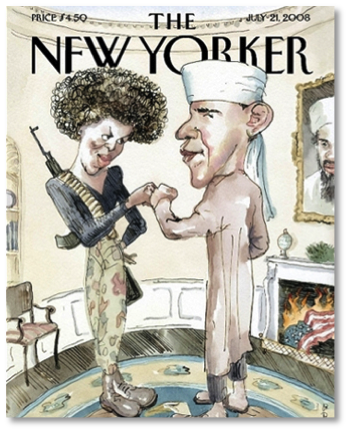

Illustration 1: The Obamas depicted as radical Muslims on the cover of the New Yorker magazine The Obamas were not immune to undesirable news frames during the 2007-08 presidential primaries. Media coverage often focused on negative perceptions of Obama, including doubts about his reliability because of his age/experience and rumors about his citizenship. Media often emphasized his ethnicity, religious beliefs and upbringing. News reports fused Arab ethnicity, Islamic faith, and the evils of terrorism so that association with one of these factors inevitably led to implications in the others. Therefore, suggesting Obama is an Arab or a Muslim translated into a sinister accusation. For instance, commentators highlighted his middle name, “Hussein,” and discussed his “questionable” associations with leaders such as Louis Farrakhan to suggest that he is a radical Muslim. The frame was best illustrated in a July cover of The New Yorker (see Illustration 1) in which the Obamas are shown “fist bumping” in the Oval Office while the American flag burns in a fireplace. The photo depicts Michelle as a militant black woman with an AK47 strapped over her shoulder. She is wearing combat boots with army-like pants and an afro (Trebay 2008). President Obama is dressed in Muslim garb including a turbine, robe and sandals. The New Yorker claimed that the cover was a criticism of the Obama family image concocted by conservative media. Likewise, journalists often used the angry black woman narrative during the 2007-2008 presidential primaries. For example, Mrs. Grievance was the caption on the cover of a July 2008 issue of National Review, which featured a photo of Michelle with a scowl on her face. The magazine’s online edition titled an essay about her stump speech “America’s Unhappiest Millionaire.” Negative coverage also centered on her statement, “For the first time in my adult lifetime, I’m really proud of my country, and not just because Barack has done well, but because I think people are hungry for change.” Many media outlets deemed the remark unpatriotic. Representations are noteworthy because stereotyping can be a social control tool to build group solidarity and create an “us versus them” mentality. People attach negative qualities depicted in the media to groups and use them to justify their oppression (Collins, 2004). In the end, stereotypes persist because ‘‘they fulfill important identity needs for the dominant culture’’ thereby maintaining the status quo and preserving hegemony (Mastro & Behm-Morawitz, 2005, p. 112). Hate groups A hate group, in a traditional sense, is any organized group that advocates hostility to a certain individual or a specific group of individuals. Customarily, the primary means by which hate groups recruited members or spread their message of intolerance were by word of mouth and by pamphleteering. In contrast, cyberspace allows hate group members all over the world to engage in real time conversations and to share the ritual and imagery that bind individuals. Hate group Web sites provide at least the facade of cohesion and collective security, a collective vision of shared fears, values, and ideologies (Meddaugh and Kay, 2009). However, on the Web, a hate group does not have to be a part of a traditional faction such as the KKK. Facebook groups allow participants to enact a lateral or bottom-up formation of their collective identities, which is different from the traditional top-down formation of identities represented by traditional media outlets. Each group contains participants from different geographical areas who collaborate in expressing revulsion for various groups. By allowing the audience to create the message as well as receive it, Facebook enables a dynamic conversation with input from every participant. Facebook’s group application is a social networking site for like-minded individuals to express their thoughts on topics and to share photos and ideas. Anyone can make a free Facebook “group” at any time. Creators choose their target, set up a page/group and recruit members (Perry and Olsson, 2009). Followers post comments, add pictures and participate in discussion boards. A Facebook “page” is similar to a “group,” except users must ‘like’ the page to become a member. Because of the ease of creating and joining such groups, many so-called “hate” groups exist only in cyberspace (Meddaugh and Kay, 2009). Defining hate In general, laws dealing with hate speech apply equally on the Internet. Hate speech is one type of speech that is not protected. It is considered any communication, which disparages a person or a group based on some characteristic such as race or sexual orientation (Levy and Karst, 2000). Most definitions of hate focus on the ways in which hate-mongers see entire groups of people as the “other.” Hate groups exhibit beliefs or practices that attack or malign an entire class of people, typically for their immutable characteristics: i.e. race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation. Matsuda (1993) supports a three-part test for determining the basis to prosecute hate speech. The first part of the test is determining if the speech encompasses a message of racial inferiority. Second, one must determine if the message targets a historically oppressed group of people. Finally, the message must be persecutory, hateful and degrading. Individual social networking websites have their own definitions of hate. According to Google and YouTube, hate speech contains language that attacks or demeans a group based on race or ethnic origin, religion, disability, gender, age, veteran status and sexual orientation or gender identity (YouTube Community Guidelines, 2012). Though sites may include offensive words, content is considered hate speech only if comments or videos target a person simply because of his or her membership in a certain group. YouTube counts on its users to know the guidelines and to flag videos that they believe violate guidelines. Similarly, Facebook invites users to report content based on the following four areas: 1) contains spam or fraud; 2) contains hate speech or attacks an individual, 3) violence or harmful behavior and nudity, pornography, or 4) sexually explicit content. However, while pornography and spam might be easy to identify, the other two categories, hate speech and attacks and individual are not as easy. Facebook’s rules include a prohibition on “content that, in the sole judgment of Company, is objectionable or which restricts or inhibits any other person from using or enjoying the Site” (Facebook Terms, 2011). In simple terms, Facebook’s code of conduct states, “certain kinds of speech simply do not belong in a community like Facebook.” It lists enumerated examples of material that is “derogatory, demeaning, malicious, defamatory, abusive, offensive or hateful.” However, even with these guidelines in place, the number of Facebook hate groups continues to flourish. Primary reasons behind the rise in hate are anonymity and access (Obeler, 2009). Creators may post anonymously, participate in various threads of discussion and cross from one group to another. The perceived obscurity of online contributors fosters bravery for many users who are not as courageous in person (Williamson & Pierson, 2003). Facebook applications allow users to recreate comparable hate pages or groups almost right after Facebook administrators delete them. For example, the groups, “There was no Holocaust” and “Holocaust is a Holohoax,” were removed because their respective members promoted race-based animosity (Bowden, 2009). However, several other Holocaust-denying groups popped up later on the Web site. Members also evade Facebook policies by spotlighting a celebrity, politician or athlete in a group’s title. Because slurs are not in the official title, Facebook is not as quick to shut them down. For example, group members target African Americans by focusing on President Obama. In one such group, he is referred to as a “nigger,” and a “no good jungle monkey.” Other groups indirectly target gays and lesbians by using stereotypes to characterize various celebrities. These groups contain foul language such as “fag” or “bull dagger.” Such groups get around Facebook rules by specifically focusing on a celebrity rather than gays in general. The definition of hate on Facebook is further muddied because there are many groups that have the word ‘hate’ in the title, but are not actually ‘hate groups.’ They are usually benign in nature. Some contain sentiments such as “I hate to go to bed,” or, “I Hate Hate.” Similar pages support causes such as “I Hate Men Who Hit Women” “I hate people who hate Obama.” Research questions Key differences in definitions and barriers to identifying hate in a social media realm illustrate the need to study and define Facebook hate groups. Based on a review of the literature, this study addresses the following research questions: RQ1: What is the historical and social context for the production of historical representations of African Americans in social media? RQ2: How do historical stereotypes and cultural narratives of black people transfer to new media representations of President Barack and Michelle Obama? RQ3: What synthesis of meaning can the researcher make from the context and structure provided by the study? RQ4: What are implications for future new media studies and critical race theory? Methods This essay utilizes a critical cultural two-part approach that addresses ideology and context. The interpretive analysis approach often outlines culture as a narrative or story-telling process in which particular “texts” or “cultural artifacts” consciously or unconsciously link themselves to larger stories in society. Ideological textual analyses use a wide range of methods to explain each dimension and to show how they fit into textual systems (Kellner, 2006). A literature review of historical representations of black women and men provided context for this study, while the content and photos on Facebook pages/groups provided the texts for analysis. To gather a sample for this study, the researcher used the keywords, “hate,” “Barack Obama,” and “Michelle Obama.” The search garnered hundreds of groups/pages (Appendix A); however, the researcher concentrated on 20 pages/groups that specifically contained the words “hate” in the title and a large number of photos and comments. Analysis began with the reading of background research on the historical and cultural conditions relative to the texts in question, which in this case was the content of Facebook groups or pages. Next, the researcher organized posts and photos into categories identified in a review of the literature. After compiling the sample posts into themes, an emergent pattern surfaced, which provided evidence for an argument about the nature of Facebook pages targeting the Obamas. Studying these themes also offered a sense of the types of Facebook groups, relative to the aforementioned historical and cultural background. Using this approach provided a comprehensive look at: 1) The ideology of race and gender 2) context of racial stereotypes, and 3) uses of Facebook to spread hate-filled messages 4) implications and solutions. Findings An analysis of Facebook pages identified several themes and missions of groups targeting the Obamas. They generally fall into two categories: hate speech and political discourse (Table 1).

Referring back to Matsuda’s three-part test, hate speech either designates a group of people as inferior; targets a historically oppressed group or includes posts that are persecutory, insufferable and degrading relating to race, gender, religion and sexual orientation. In this case, such groups indirectly spread hatred toward women and Blacks by targeting the Obamas with racist and sexist rhetoric. Titles included “I don’t discriminate, I hate the white part of Obama too," and “Yes, I hate Obama because he’s black. That’s exactly why." Group creators expressed their personal viewpoints and rallied support from others who shared unflattering photos, comments and links to articles containing racist and sexist discourse. In contrast, political groups targeted the president’s administration, partisan issues and financial decisions. Members hate Obama for a variety of reasons. Some disagree with his position on issues such as universal healthcare or are angry about how he handled the BP Oil Spill. Others believe his campaign promises were lies, and still others openly dislike him because of his skin color. For instance, the group, “I Hate Obama," encouraged members to post their ideas on the prominent public figure and his policies (Figure 2).

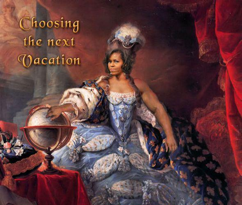

Figure 3. Political Facebook hate pages targeting President Obama Pictures included captions that highlight his campaign slogans. One cutline stated, “How’s all that hopey changey stuff workin’ out for ya?” Another caption altered a campaign poster and replaced the word “change” with “fraud” (Figure 3). Pages also contained links to news reports and other articles along with comments such as, “why did obama keep silent when irani opponents of faqih and najjad protested by millions in 2009 while he insisted that mubarak resign from egypt immediately (sic)?” Facebook users also highlighted the idea that the Obamas are living lavishly. One photo featured Mrs. Obama toasting with a champagne glass. The photo’s caption stated, “The first lady making a toast to other people’s money.” In another photo, her face is superimposed onto the body of a queen. She has a masculine arm that points to a globe. The caption stated, “Choosing the next vacation.” To support the idea that she is overspending, the creator posted links to articles with titles such as “Michelle Obama Hosts $100K per Couple Soiree” and “Group sues for Michelle Obama vacation records” (Figure 4).

Figure 4. I Hate Michelle Obama Similarly, users targeted Michelle’s health initiatives to encourage Americans to exercise and eat healthy. The page titled, “I hate it when Michelle Obama tells me I’m obese," had more than187 members as of March 2012 (Figure 5). In this group, fans harped on the idea that the first lady has taken the fun out of eating at school and she is a hypocrite. For example, one fan stated, “I go to the vending machines to get my usual Orange Crush or Coke (since they don’t stock Pepsi)... so I look at the machines and lo and behold - nothing but WATER and some kind of pissy Vitamin Water crap? Thanks a lot Michelle - take your big lard ass and involve it in some other endeavors." The page titled, “I hate Michelle Obama," targeted Mrs. Obama’s obesity campaign with photos and comments such as, “I'm announcing my own initiative: ‘Let's Move! Michelle's Fat Ass Out of the White House."’ The page’s creator included comments such as, “She (Mrs. Obama) cited “remarkable progress" on her ass almost fitting through doors," and “Food is love, she grunted like an animal, not understanding how words work." Even groups that claimed to be politically motivated utilized racist rhetoric. The mission statement for the group, “No! I don’t hate blacks! I just think Barack Obama is a terrible president," asked the question, “don’t you just hate it when people call you racist because you hate Barack Obama? Do they ever consider that Barack Obama may just be a shitty president?" However, while stating the group’s dislike for Obama is not because of his race, most comments on the page attacked him personally with racial slurs. Posts included statements such as “Obama needs to step down and go back to Africa with the rest of the coons!! He’s nothing but a jigaboo and spear chucker!! (sic)." This site was archived and later removed from Facebook.

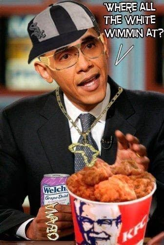

Figure 5. Many hate groups target Michelle Obama’s obesity campaign Illustrating stereotypes identified in the literature, many groups emphasized the Obamas’ dietary habits. One photo featured Mr. Obama holding a can of Welch’s grape soda and wearing stereotypical garb. The photo’s caption asked, “Where all the white wimmin at (sic) (Figure 6)?” In response to the photo, members posted comments such as, “Roffl (rolling on the floor laughing).” “I think i pissed my pants.” “haha awesome pic,” “the welch thing should be koolaid not grape juice! and there should be a watermelon and chicken farm in the back (sic)!”

Figure 6. Facebook photos featuring President Obama in stereotypical garb

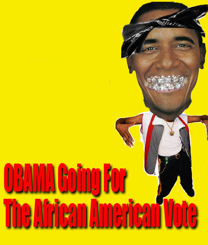

Figure 7. Facebook page titled, “Obama Sucks” Members also targeted Mrs. Obama with similar racist rhetoric. For instance, one person wrote, “Chilin wit Moochelle Obamaa. You see Barry is a good man he gave Moochelle chitlins and peanut butter for breakfast (sic).” In another example, a member’s post targeting Obama resulted in this negative portrayal of Mrs. Obama. 1st thing Obama does in the morning....bow to Allah. 2nd...log on to rasmussen.com to check his polls. 3rd... Attend/ organize next fund raiser. 4th... Compose smoke and mirrors rhetoric for his Facebook page. 5th....Repeat. In response, another member stated, “You forgot pry the piece of chicken or watermelon out of Moochelle’s (sic) mouth.” Pages build on ideas that black people are different from members of the dominant group. Several photos featured Mrs. Obama dancing with comments about her “always jigging.” The “Obama Sucks” group primarily serves as an outlet to post comical Photoshopped photos of the president (Figure 7). One photo features him wearing a bandana and gold teeth. The photo’s caption states, “Obama going for the African American vote.” Other Facebook groups targeting the two included sarcastic comments. For example, a group titled, “Woah, Obama and Bob the Builder Have the Same Catchphrase,” refers to Obama’s campaign slogan, “Yes, we can.” While humorous, the site hints that his campaign was overly simplistic. Another group in this category was titled, “Dear Lord, this year you took my favorite actor, Patrick Swayze, my favorite actress, Farah Fawcett, my favorite singer, Michael Jackson. I just wanted to let you know that my favorite president is Barak Obama.” Animalistic stereotypes Many Facebook hate pages focused on cultural narratives mentioned in the review of the literature. Animalistic photos depict Obama or his whole family as animals, particularly apes. One photo includes male and female apes holding an infant ape with Obama’s face superimposed on its face (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Photos depicting the president as animalistic and foreign

Figure 9: Modern stereotypes include hints of old cultural narratives: alien, animalistic and foreign

Figure 10. Photoshopped photos depicting Michelle Obama as extravagant, masculine and foreign Likewise, another group included a photo of an ape dressed in a suit with a caption underneath that stated “NoBama ’08.” The photo undoubtedly is from the 2008 election; however, it is still prominently displayed on the page of a Facebook group (Figure 9). Similarly, the site titled, “I hate Michelle Obama,” had dozens of photos that portrayed the first lady in a stereotypical manner. For instance, the caption for a photo of her superimposed onto the set of the TV show, “iCarly,” stated, “Carly, there’s a baboon in your basement (Figure 10).” Angry, deviant, evil Sexist images discussed in the literature are plentiful on Facebook. Unflattering photos highlighted Mrs. Obama scowling and making angry gestures. Other photos depicted her as masculine and unattractive. For instance, in one image, she has a superimposed mustache on her face (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Photos from the Facebook pages that imply Mrs. Obama is masculine, angry and evil

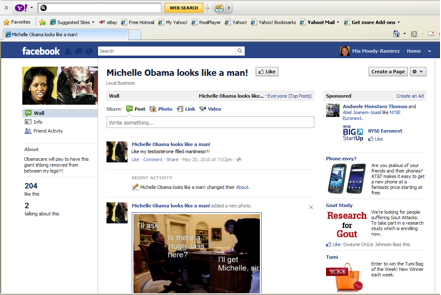

Figure 12. The Facebook page, “Michelle Obama looks like a man”

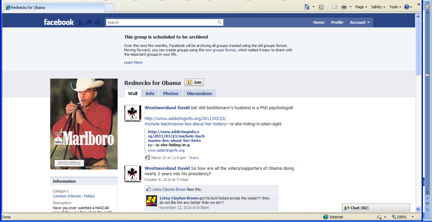

Figure 13. Many Facebook hate groups compare Michelle Obama to other people or characters. Many groups portrayed her as masculine and unattractive by placing her picture next to another person or character such as the Predator or James Brown. Titles included, “Is it me or does Michelle Obama look like James Brown?” “Michelle Obama is Creepy,” “Michelle Obama’s face scares me” and “Michelle Obama looks like a man” (Figure 12). The mission statement for the group titled, “Michelle Obama looks like a man,” declares, “Obamacare will pay to have this giant shlong removed from between my legs!!!” Fans post comments such as, “She has man hands” and “I heard she is pregnant.” To support their claims, members posted unbecoming photos of the first lady depicting her as angry. Similarly, the group, “I painted a mustache on Michelle Obama...Oh wait, that wasn’t necessary,” also focused on her looks rather than her political works. Demonstrating how sexist stereotypes have made their way onto social media, numerous posts piggyback on the angry black woman stereotype. For instance, one member stated, “The woman is evil.” Another group compared her to Queen Marie Antoinette of Austria. These are all powerful images and portrayals that serve to make the first lady appear ugly, mean, aggressive and wicked (Figure 13). The gatekeeper’s role While each group’s content varies, facilitator participation is the driving factor in their level of involvement and effectiveness. The most popular groups have facilitators who post frequently and respond to posts by other members. Creators must moderate and actively participate in disseminating messages. Without an active facilitator, pages contained spam, which indicated they are unmonitored and unorganized. Similarly, groups that contain walls riddled with grammatical and spelling errors were not as affective. Pages that include a mission statement also appear more affective. Not only do they make the objectives of the page clear, they also let visitors know right away what the group advocates. This is particularly important on pages that are member rather than facilitator driven. Administrators who do not have time to delete inappropriate or unrelated comments must clarify a group’s purpose up front. Successful sites also have facilitators who suggest discussion topics rather than allow members to control the group’s themes. For example, one hate group targeting President Obama encouraged members to explain their dislike for him and to discuss his policies in an educated manner. Conversely, another group that had less regulation by the creator, included topics such as, “Obama will destroy you and eat your babies.” Therefore, the page appeared less organized and hence less credible. Status updates are another way facilitators can guide the content and mission of the page. Status updates posted by creators include links to articles, photos or information to support the group’s stance. Popular posts receive favorable feedback from members who can ‘like’ them. The most popular groups are those that have facilitators who post frequently and respond to posts by other members. Worth noting is the participatory flow of information fostered by the Web has expanded and sometimes leveled the playing field for underrepresented groups. Obama supporters visit hate groups to help diffuse negative messages and to post information along with his detractors. Similarly, groups diffuse online animosity with positive pages. “Love-Hate” groups favor the president and first lady, but express their support by using hate in the title such as “I hate it when Republicans hate on Obama” and “I hate it when people blame Obama for Bush’s mess.” For example, “What The F** Has Obama Done So Far,” is actually a positive page. Each time users click a link that asks, “What Obama has done so far,” then a positive story or news release about the president’s efforts pops up. Articles focus on issues such as expanding funding for student loans and passing hate crime laws. Humorous pages foster support for the president using wit. For example, the group, “Rednecks for Obama,” asks the following questions, “Have you ever watched a NASCAR race all the way through to the end? Have you ever shot at rats with a Beebe gun in a trash dump on a Friday night? Do you have your own food pyramid with pork rinds on the bottom and slim jims on the top (sic)? Do you also think that Obama would kick ass as the next president?” Then this is the group for you (Figure 14). This group has been archived and is no longer online.

Figure 14. Facebook groups targeting the Obamas Implications This study looked at the Facebook hate pages targeting President Barack and Michelle Obama. Study highlights indicate that while the potential for making a positive impact is present, social media outlets often serve as a new avenue for spreading “old” messages of hatred. Findings indicate Facebook groups give individual users an opportunity to have their voices heard about topics that they feel strongly about. Such platforms have become the Generation Y’s way of protesting. Posting on a Facebook page can be cathartic and offer a safe haven for people to express political ideas in an environment without feeling they may be ridiculed. However, when people become uncivil or disrespectful, groups get out of hand and become a page of political junk. In some instances, hate groups are a form of cyber bullying, particularly when creators and members attack a person based on his or her race, religion and sexual orientation. Findings indicate pages and groups are usually divided into two categories: political discourse and hate speech. Political hate groups primarily focus on partisan discourse. They consist of Facebook members who have an interest in politics and use social media to share their ideas. Conversely, Facebook hate groups depict the two in a stereotypical manner. They are featured wearing ethnic garb, eating soul food and participating in various activities such as dancing and playing basketball. In sum, they focus on the Obamas’ personal character, gender and race rather than politics. Three primary implications emerged based on this analysis. First, findings indicate although historical stereotypes focusing on diet and blackface have all but disappeared from mainstream television shows and movies, they have resurfaced in new media representations. Facebook hate group portrayals incorporate negative viewpoints of black people and their perceived roles in society that storytellers have used for generations. Findings demonstrate that historical representations of the group are still strong and have an impact on modern portrayals. Similarly, Facebook users play up shallow, patriarchal representations of Mrs. Obama, focusing on her femininity, appearance and personality. Facebook members who have a hard time accepting a black woman in the role of first lady of the United States attempt to explain the occurrence in a recognizable package by focusing on physical appearance instead of her capabilities. From a patriarchal viewpoint, sexist rhetoric implies although she is in a prominent position; she is not important to mainstream society because she “looks like a man” and does not fit their ideal of a first lady. This “us” versus “them” imagery found in Facebook portrayals suggests a step backwards in civil rights gains. Gatekeeper/audience functions Secondly, the medium challenges traditional paradigms in the areas of gatekeeper and audience roles. Findings are significant because social media outlets change gatekeeper dynamics, enabling communicators to directly reach audiences. Historical representations of African Americans have transcended to a new media platform, introducing blackface portrayals to a new generation. Without traditional gatekeepers to suppress such messages, the watchdog role is left to scholars. Mass media forms such as newspapers and broadcasting were conceptualized as “one-to-many” communication. On the other hand, Facebook and similar media forms foster “many-to-many” communication because not only can one person reach a wide audience, but audience members can also contribute to the overall creation of the message by talking back to the producer and to each other. In addition, users rather than editors and publishers police the content of Facebook pages. Demonstrating a shift in gatekeeper functions, facilitator participation is usually the driving factor in each group’s level of involvement and effectiveness. Group facilitators may decrease hate speech by encouraging comments that are not sexist or racist. In addition, they might delete comments that are rude and unnecessary to inspire dialogue that focuses on news items and political events. Other ineffective groups include walls full of profanities that clearly do not present the views and goals of the group. Without an active facilitator, many pages contain grammatical and spelling errors and spam, which indicates they are unmonitored and unorganized. A group’s credibility is often hurt by the prominence of misspelled words, spam and poor grammar, demonstrating the importance of a good administrator. The participatory flow of information has expanded and leveled the playing field for audiences. Facebook illustrates this shift in audience theory. Whereas previously, audiences could not respond to rhetoric immediately, Facebook offers a platform allowing them to respond instantly in a public forum. Facebook hate groups give individual users an opportunity to have their voice heard about topics they feel strongly about. For instance, Obama supporters helped diffuse negative messages by posting Facebook walls along with his detractors. Results illustrate the extent to which new media innovations have changed the communication landscape forever. Historical communication theorists such as Shannon and Weaver (1949), Schramm (1954), Lasswell (1960), and Berlo (1960) attempted to reduce communication into components and then operationalize and correlate them with other variables. Horkheimer & Adorno (1972) believed media are disseminated to a passive audience who, numbed and alienated by mass production, accept them without question. Traditional theories have become less accurate in today’s media culture. Because media encourage participation and interaction; users are both distanced readers and authors in a collective online community. Additionally, rather than encouraging alienation, social media open up a forum for anyone who cares to participate. Most information posted to the walls of Facebook hate groups is the opinions of individual users. Findings point to the necessity of rethinking and retesting traditional communication theories as social media change gatekeeper and audience roles. As mass media continue to transform, the need to study group interactions in new media environments increases in importance. Existing media theories and models are the most efficient way to study trends. This study provides a qualitative overview of the types of groups present; however, future studies might add a quantitative component to provide insight into the intricacies of hatred on Facebook. Furthermore, uses and gratification theories must be revisited. Using an integrated approach to audience studies, scholars must look at demographics such as gender, class and race and their impact on Facebook virtual relationships and sharing activities. Such studies might benefit from an analysis of survey responses of hate group creators and members to get a sense of motivating factors in their use of different media. In-depth interviews would provide a wealth of information to help scholars assess the dynamics at play. Freedom of speech Thirdly, scholars must continue to explore social media and the dynamics of freedom of speech. The ideals of free expression allow even the most abhorrent speech in the marketplace of ideas to ensure a democratic society. It is important to ask what kind of psychological impact these groups can have on their subjects/members. For example, hate groups might foster an environment in which violence and disruptive actions are acceptable. While more research is needed to assess the long-term effects of hate speech, very limited restrictions on some hate expression may be worth considering. Undesirable content available on the Web has fostered intense debate about whether it is best to forget about policy and let human agency determine citizen use of media. Proponents of critical political economy argue that the market alone cannot regulate media diversity. Harris, Rowbotham & Stevenson (2009) suggest looking to historical parallels for fruitful and workable solutions to censorship. They question whether current legal approaches to hate speech are practical and appropriate. They also question the extent to which the transposition of ‘real life’ regulation can be imposed onto ‘virtual life’ regulation. Bollinger’s vision of an open forum encompasses the Internet. In his model, bigoted speech is exposed by more speech that decries bigotry, which ultimately illuminates a larger, more tolerant truth within society. In the end, positive speech may be one the best ways to stifle hate speech. When advocacy groups work together and use the new technology at their disposal, they have a way of signaling out bad speech and bad ideas. Instead of restricting free speech, Gelber (2002) proposes ‘speaking back,’ which involves such things as government funding for local newsletters to respond to episodes of hate speech in a specific community, or the development of an anti-racism program in a workplace, in which hate speech has taken place (p. 123). These solutions all rely on a person’s ability to accurately define and identify actual cases of “hate speech.” Defining hate Lastly, users must be able to identify hate. Henry (2009) examined the evolving legal jurisprudence in the United States regarding prosecutions of hate speech on the Internet. He asserts that working with ISPs to remove offensive content has significant limitations. Ultimately, the ISP itself has the final determination over whether it will cooperate. Therefore, citizens must continue to keep a watchful eye on their own actions and recognize hate speech when they see it. An inevitable problem in any discussion of hate speech lies in the difficulty of defining the term. As mentioned in the literature review, Facebook users cannot identify hate speech as easily as they can nudity, pornography and harassing personal messages. One way to identify hate groups is to assess if members disseminate hate speech. This study offers a litmus test that includes strategies suggested by Matsuda’s three-part test. According to this test, hate speech:

Audiences must also be aware that Facebook group/page titles are not always an indication of a group’s platform. For example, hundreds of Facebook hate groups indirectly target gays by characterizing celebrities as gay, then launching stereotypes and slurs at them. Many Justin Bieber hate groups contain foul language mainly focused on addressing his sexuality and his music. Some posts threaten to either kill him or wish him dead. However, such groups get around Facebook rules by specifically focusing on Bieber rather than gays in general. Because “fag” or “gay” are not in the official title, Facebook is not as quick to shut down this type of site. Rhetoric promoted by the groups is nonetheless offensive and violence provoking. Also worth noting is photos are a remarkably strong way to disseminate hate. Many Facebook pictures highlight the president and first lady adorned with features that are meant to be negative or funny such as beards, afros, mustaches, gold teeth, do-rags and various costumes. Hence, President Obama is depicted as a rapper, Muslim and social deviant. Mrs. Obama is depicted as a masculine, unattractive “angry black woman.” Most pictures are accompanied with a disrespectful caption that relays a negative message. Most photo captions do not attack the president and first lady’s political views; instead, they attack them personally with racial slurs that build on racist historical narratives depicting Blacks negatively. The shocking nature of these pictures spur numerous comments and likes. Photos are often more effective than words as one can look at a picture and almost instantly understand the views held by group members. Conclusions Facebook’s group application is a free social networking site for like-minded individuals to express their thoughts on topics and to share photos and ideas. This convenient capacity for social interaction has created yet another avenue for spreading hatred. As a result, Facebook serves as host to a large variety of ‘hate’ groups and pages on the Web. Study findings indicate Facebook hate groups/pages differ from traditional hate groups and do not have to be a part of a traditional faction such as the Ku Klux Klan. Anyone can create a Facebook group or page anywhere, and then recruit members from all over the world. In general, hate groups, fall into two categories—politics and hate speech. Hate groups indirectly spread hatred toward women and blacks by targeting the Obamas with racist and sexist rhetoric. Unflattering photos, comments and articles containing racist and sexist discourse frame the two negatively. While political pages offer some educational value by emphasizing the President and first lady’s political platform, hate pages primarily focus on personal characteristics such as their culture, dietary habits, attire and physical features. Users share derogatory comments about the two playing basketball, dancing and eating items such as watermelon and chitterlings. Animalistic photos depict Obama or his whole family as animals, particularly apes. Findings demonstrate historical stereotypes have made their way onto social media applications. Findings are important as perceptions and stereotypes often become the dominant viewpoint whether they are accurate or not. Worth considering is creating literacy programs that encourage adolescents and adults to identify and seek positive, accurate messages in social media. Media literacy curriculum must be updated and adjusted to accommodate shifts in the communication paradigm. Whereas previous literacy programs focused on television, newspapers and cinema, new pedagogy should teach students how to read and critically dissect Internet content. Academia must also encourage public discussions and essays such as this one, which will help keep the discussion on people’s minds. In the end, tolerance should be encouraged that allows all people to share their views without destroying someone else’s character or spreading hate speech. Scholars of the 21st Century must fully explore the impact of social media on political development and decision-making in this new communication environment. Of interest is the influence of media and the roles of authors, publishers and audiences. Analyses must evaluate underlying ideologies, frames and stereotypes found in social media to help document this phase in history. Going forward, social media outlets such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Pinterest and Google+ offer unlimited content for scholars to study. This study provides a good foundation. References Amster, S. (In press). From Birth of a nation to Stormfront: A century of communicating hate. In B. Perry & B. Levin (Eds.), Hate crimes: Understanding and defining hate crimes. Connecticut: Praeger Perspectives, Greenwood Press. Back, L. (2002). Aryans reading Adorno: Cyber-culture and twenty-first century racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25(4), 628-651. Benedict, H. (1997). Virgin or vamp: How the press covers sex crimes. In L. Flanders (Ed.), Real majority, media minority (pp. 115-118). Maine: Common Courage Press. Berlo, D. (1960). The Process of Communication. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Biagi, S. (2007). Media/impact: An introduction to mass media. CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Blinde, E. & McCallister, S. (1999). Women, disability, and sport and physical fitness activity: The intersection of gender and disability dynamics. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 303-312. Billings, A. (2003). Portraying tiger woods: characterizations of a ‘black’ athlete in a ‘white’ sport." The Howard Journal of Communications. (14), 29-37. Bird, S. (1988). Myth, chronicle and story: exploring the narrative qualities of news . In J. Carey, Media, myths and narratives: Television and the press. New York: Sage. Bowden, R. (2009). Facebook hate group ban opens questions of free speech and consistency by - May 12 2009, 04:19 http://www.thetechherald.com/article.php/200920/3650/facebook-hate-group-ban-opens-questions-of-free-speech-and-consistency Boylorn, R. (2008). As seen on TV: An Auto ethnographic reflection on race and reality television. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 25(4), 413-433. doi:10.1080/15295030802327758 Carter, C. & Steiner, L. (2003). Critical Readings: Media and Gender. Maidenhead: Open University Press. Childs, E. (2005). Looking behind the stereotypes of the “angry black woman": An exploration of black women’s responses to interracial relationships. Gender & Society, 19(4), 544-561. doi:10.1177/0891243205276755 Chomsky, N. & Herman, S. (1988). Manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media. New York: Pantheon Books. Collins, P. (2004). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender and the New Racism. New York: Routledge. Counihan, C. & Esterik, P. (1997). Food and Culture: A Reader. Routledge: New York. Dates, J. & Barlow, W. (1993). Split image: African-Americans in the mass media (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press. Disliking-Michelle-Obama Facebook Page. Retrieved on June 1, 2011, http://www.facebook.com/pages/Disliking-Michelle-Obama/169702349754252#!/photo.php?fbid=169702766420877&set=a.169702763087544.42494.169702349754252&type=1&theater Douglas, S. (1995). The framing of race. Progressive, 59(12), 19. Retrieved from Academic Search Complete database. Drummond, W. (1990). About face: From alliance to alienation blacks in the news media. American Enterprise, 1(4) 24-29 Effron, D., Cameron, J. & Monin, B. (2009). Endorsing Obama licenses favouring whites’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 81, 33-43; also cited in Chicago Tribune’ article by Richard Fausset, ‘Studies of racial attitudes grapple with Obama Factor’23(8). Enriques, E. (2001). Feminism and feminist criticism: An overview of various feminist strategies for reconstructing Entman, R. (2000). The black image in the white mind: Media and race in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Entman, R. and Rojecki, A. (1993). Freezing out the public: Elite and media framing of the U.S. anti-nuclear movement, Political Communication (10),155-173. Facebook, Terms of agreement http://www.new.facebook.com/terms.php?ref=pf Ferri, A. & Keller, J. (1986). Perceived career barriers for female television news anchors. Journalism Quarterly, 63, 463-467. Frankel, E. (2004). Freedom of Speech, Vol. 21. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Freeman, B. & Chapman, S. (2007) Is YouTube telling or selling you something? Tobacco content on the YouTube video-sharing website. Tobacco Control, 16(3), 20 Gelber, K. (2002). Speaking Back: The Free Speech versus Hate Speech Debate. John Benjamins Publishing. Gitlin, T. (1980). The Whole World is Watching. Berkeley: University of California Press. Giuliani spokeswoman Katie Levinson comments on Clinton’s health plan. (Sep. 17, 2007) Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks (Q. Hoare & G.N. Smith Eds.). New York: International Publishers. Grimm, J. (2007). Mirror, Mirror: Hegemonic Framing of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., in the New York Times. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, San Francisco, CA. Hall S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972-79, ed. S Hall, pp. 128-38. London: Hutchinson Harris, C. Rowbotham, J. & Stevenson, K. (2009). Truth, law and hate in the virtual marketplace of ideas: perspectives on the regulation of Internet content. Information & Communications Technology Law, 18(2),155-184 Henry, J. (2009). Beyond free speech: novel approaches to hate on the Internet in the United States. Information & Communications Technology Law, 18 (2), 235-251. hooks, B. (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press. Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. (1972). Dialectic of Enlightenment. (J. Cumming, Trans.). New York: Herder and Herder. I hate it when Michelle Obama tells me I’m Obese. Facebook Page. Retrieved on March 1, 2011, http://www.facebook.com/#!/pages/I-hate-when-Michelle-Obama-tells-me-Im-obese/116159791732970 I painted a mustache on Michelle Obama...Oh wait that wasn’t necessary. Retrieved on June 1, 2011, http://www.facebook.com/#!/group.php?gid=125390744140630&v=wall I-Hate-Obama. Facebook page. Retrieved on March 1, 2011, from http://www.facebook.com/pages/I-Hate-Obama/314569782587 Jhally, S., & Lewis, J. (1992). Enlightened racism: The Cosby Show, audiences and the myth of the American Dream. Boulder: Westview Press. Kaiser, C., Drury, B., Spalding, K., Cheryan, S., & O’Brien, L. (2009). The ironic consequences of Obama’s election: Decreased support for social justice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 556-559. Kellner, D. (2006). Cultural Studies, Media Spectacle, and Election 2004. InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies , 1-16. Knowles, Lowery and Schaumberg (2009). Racial prejudice predicts opposition to Obama and his health care reform plan. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Kohut, A. (2007). Most Say Imus's Punishment Was Appropriate: Whites Say Imus Story Has Been Overcovered, Blacks Disagree. Washington DC: The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press . Lassiter, J. (1979). Meta-anthropology, normative culture and the anthropology of development. A paper read at the 1979 Annual Meeting of the Northwest Anthropological Conference, Eugene, Oregon, March 23. Lasswell, H. (1960). The structure and function of communication in society. In W. Schramm (Ed.), Mass Communications. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Leets, L. (2001). Responses to Internet hate sites: Is speech too free in cyberspace? Communication. Law & Policy, 6(2) 287-317. Levinthal, D. & Diawara, M. (1999). Blackface. Aldershot: Arena Levy, L., & Karst, K. (2000). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution Vol. 3. (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York: Macmillan. Lubiano, W. (1992). Black ladies, welfare queens, and state minstrels: ideological war by narrative means. In Maas, K. & Holbrook (2001). Media promotion of the paradigm citizen/golfer: an analysis of golf magazines’ Representations of disability, gender, and age. Sociology of Sport Journal, (18), 21-36. Morrison, T. (Ed.), Race-ing justice, en-gendering power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the construction of social reality. New York: Pantheon Books. Ludvig, A. (2006). Differences Between Women? Intersecting Voices in a Female Narrative . European Journal of Women's Studies , 245-258. Martindale, C. (1990). Changes in newspaper images of Africans Americans. Newspaper Research Journal, 11(1), 46-48. Mastro, D. E., & Behm-Morazwitz, E. (2005). Latino representation on primetime television. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(1), 110-130. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. May 14, 2008 Facebook’s New Friends Abroad. Business Week. McLuhan, M. & Fiore, Q. (1967). The Medium is the Message. New York: Bantam Books. McNamee, L., Peterson, B. & Pena, J. (2010). A Call to Educate, Participate, Invoke and Indict: Understanding the Communication of Online Hate Groups. Communication Monographs, 77(2), 257-280. doi:10.1080/03637751003758227 Meddaugh, P. & Kay, J. (2009). Hate Speech or “reasonable racism?" the other in stormfront. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 24(4), 251-268 Memmott, M. (2005, June 15). Spotlight skips cases of missing minorities. USA Today. Meyers, M. (2004). African-American women and violence: Gender, race, and class in the news. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 21(2), 95-118. Mill, J. (1869). On Liberty. London: Longman, Roberts & Green. Moraga, C. & Anazaldúa, G. (1981). This bridge called my back: Writings By radical women of color. Watertown: Persephone Press. Nachbar, J. & Lausé, K. (1992). Popular culture: An introductory text. Wisconsin: Popular Press. Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth (1984), The spiral of silence. A theory of public opinion - Our social skin, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Obeler, A. (2009). Google Earth: A New Platform for Anti-Israel Propaganda and Replacement Geography. Jerusalem Issues Brief, Vol. 8, No. 5 Ono, K. (2009). Contemporary Media Culture and the Remnants of a Colonial Past. New York: Peter Lang. Orbe, M. (1998). The Relationship between Communication and Power. In In J.N. Martin & T. K. Nakayama. Intercultural Communication in Contexts (pp. 100-101). New York: McGraw-Hill. Origins of Racist Terms, 2011 http://www.thebirdman.org/Index/Others/Others-Doc-Race&Groups-General/+Doc-Race&Groups-General-General&Msc/RacistTerms&Origins.htm Parenti, M. (1997). Methods of media manipulation. Humanist, 57(4), 5. Perry, B. & Olsson, P. (2009). Cyberhate: the globalization of hate. Information & Communications Technology Law, 18(2), 185-199. doi:10.1080/13600830902814984 Poindexter, P., Smith, L. & Heider, D. (2003). Race and ethnicity in local television news; framing, story assignments, and source selections. Journal of Broadcast 7 Electronic Media, 47, 524-540. Project for Excellence in Journalism and the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press Politics and Public Policy. October 27, 2007. Redneck Group Page. Facebook page. Retrieved on March 1, 2011, http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=13396028359&v=app_2373072738#!/group.php?gid=13396028359&v=wall Reed, C. (2009). The challenge of hate speech online. Information & Communications Technology Law, 18(2), 79-82. Renn, K. (2004). Mixed race students in college: the ecology of race, identity, and community. Albany: State University of New York Press. Robinson, E. (2005, June 10). (White) women we love. The Washington Post, p. A23. Schell, L. (1999). Socially constructing the female athlete: A monolithic media representation of active women. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas Woman’s University, Denton. Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of mass communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Shannon, C., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Shoemaker, P. (1991). Communication concepts : Gatekeeping. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. Springer, K. (2007). Divas, evil black bitches, and bitter black women: African American women in postfeminist and post-civil-rights popular culture. In Interrogating postfeminism: Gender and the politics of popular culture (pp. 249-276). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Squires, C. (2007). Racial mixed people. Dispatches from the color line: The press and multiracial america. Albany: State University Of New York Press. Strudler, K., and Schnurer, M. (2006). Race to the bottom: the representation of race in ESPN’s playmakers. Ohio Communication Journal. 44: 125-150. SWC (2009). iReport of online hate groups. Simon Wiesenthal Center (SWC). Retrieved June 1, 2011, at www.wiesenthal.com/site/apps/nlnet/?content2.aspx? Trebay, G. (2008). Fashion diary: She dresses to win http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/08/fashion/08michelle.html?n=Top/Reference/Times%20Topics/People/T/Trebay,%20Guy Van Zoonen, L. (1994). Feminist media studies. London: Sage Publications. Washington, A. (July 5, 2008). Black women rally to Michelle. Washington Times. West, C. (2001). Race matters. Boston: Beacon Press. White, D. (1950). The gatekeeper: A case study in the selection of news. Journalism Quarterly, 27(4), 383-390. Williamson, L. & Pierson, E. (2003). The rhetoric of hate on the Internet: Hateporn’s challenge to modern media ethics. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 18(2), 250-267. Yarborough, M. & Bennett, Y (2000). Mammy sapphire jezebel and their sisters. The Journal of Gender, Race & Justice Accessed July12, 2011 at http://academic.udayton.edu/race/05intersection/Gender/AAWomen01a.htm

Dr. Mia Moody is a professor of Journalism and Media Arts at Baylor University. She teaches courses in public relations campaigns, minorities and women in the media and reporting and writing. She is the author of Black and Mainstream Press’ Framing of Racial Profiling: a Historical Perspective, published by University Press of America in 2009. |

||||||||||