Victorian Translators: Stephen W. White and William Struthers

Revealed.

by Norman Wolcott and Kieran O'Driscoll

© May 2008

Who was Stephen White?

Stephen White (July 16 1840—1910+) and William Struthers (October 14

1851—1930+) translated five stories of Jules Verne:

I. * The Tour of the World in Eighty Days, tr. by Stephen W. White,

Philadelphia Evening Telegraph: June 27, 1874--July 17, 1874; reprinted by

Charles E. Warburton (Bound together with II.)

II. A Fancy of Doctor Ox , tr. by Stephen W. White, Philadelphia

Evening Telegraph, June 20, 1874: reprinted by Warburton, (Bound together with

I.)

III. *

A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, tr. by Stephen W. White,

Philadelphia Evening Telegraph: Sept. 12, 1874--Oct. 5, 1874, reprinted by

Warburton. (Bound together with IV.)

IV. A Winter’s Sojourn in the Ice, tr. by William Struthers,

Philadelphia Evening Telegraph: Oct. 6, 1874--Oct. 10, 1874, reprinted by

Charles E. Warburton. (Bound together with III.)

V. Mysterious Island, Philadelphia Evening Telegraph: 1876,

republished Project Gutenberg: 2003 (N. Wolcott and Sidney Kravitz,

eds.)

Those of us who attended the NAJVS meeting in Albuquerque last year were

swept off our feet by the lecture of Kieran O'Driscoll of Dublin on the "80

Days" translations of Jules Verne. For the first time many of us heard the

translations of JV discussed from a linguistics point of view. After some

chatting we exchanged e-mails, and Kieran mentioned that his professor had

suggested that he use as a second sample a translation of "80 Days" with a known

person as translator. (Kieran had been using the anonymous Ward Lock version as

no 2). He said he had had difficulty obtaining a copy of the Frith translation

at a reasonable price. I suggested he try getting the White translation which

was readily available on Ebay for a few dollars, which I said seemed to be a

fairly literal rendition. This he did, and I received an e-mail 07 September

2007 stating:

"I have been studying sections of the White translation of TM (80

Days) in detail and find it to be generally of a meticulously accurate

standard, and as literal as possible, consistent with the natural TL (Target

Language) formulation..."

It now seemed that White might be entitled to an upgrade from the black ball

he received for his Mysterious Island translation.

On 17 October 2007 I received the following e-mail:

I thus found, on the website, Ancestry.com, to which I am a subscriber,

details of a Stephen W. White, born in Pennsylvania in about 1841, thus in his

thirties when he first published his version of TM... One thing I am intrigued

by and wish to ask your opinion on - White's occupation is listed on that 1880

Census as 'Secretary - N.C.R.R.' ... my hypothesis thus far is that it may refer

to the North Carolina Railroad Company, Carolina also being on the East coast,

and the railroad originally dating back to the 1840s in Carolina and still using

the initials NCRR, not NCRC as one might logically expect.

I replied that I thought the North Carolina RR was too far from Philadelphia,

but I would do more looking. This work was done at Library of Congress (LOC)

which subscribes to all Ancestry.com databases and numerous newspaper archives.

On 18 November 2007 I wrote:

In the 1910 census...the address is listed as 70 Broad St. At the right in

handwriting beside SWW under occupation is "Secy of Northern Central

RR"

So now the mystery was solved—NCRR was the Northern Central Railway, but what

was that? A little "googling" revealed a Wikipedia article and several other

websites and the following information was included in my e-mail to Kieran of 19

November 2007:

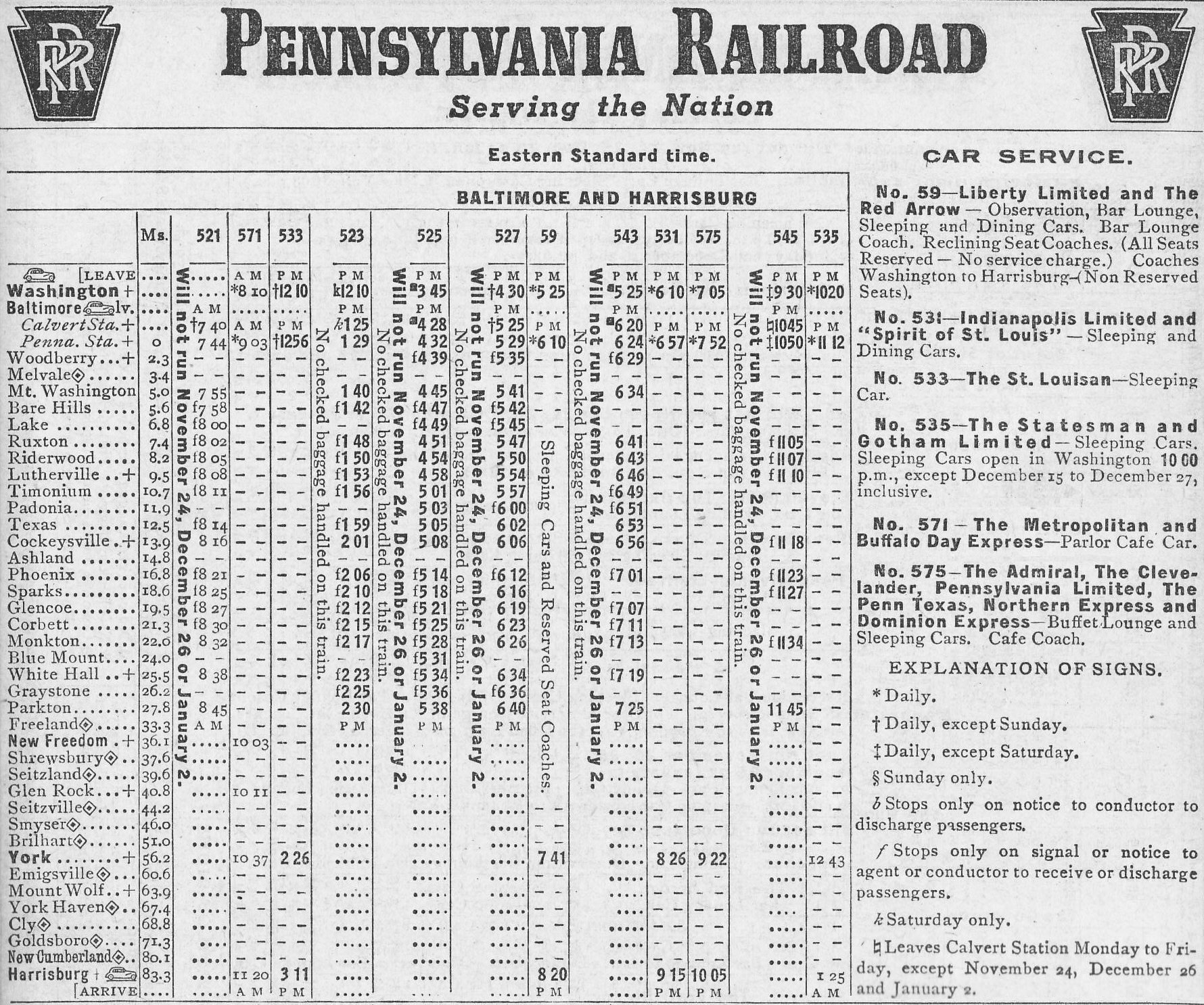

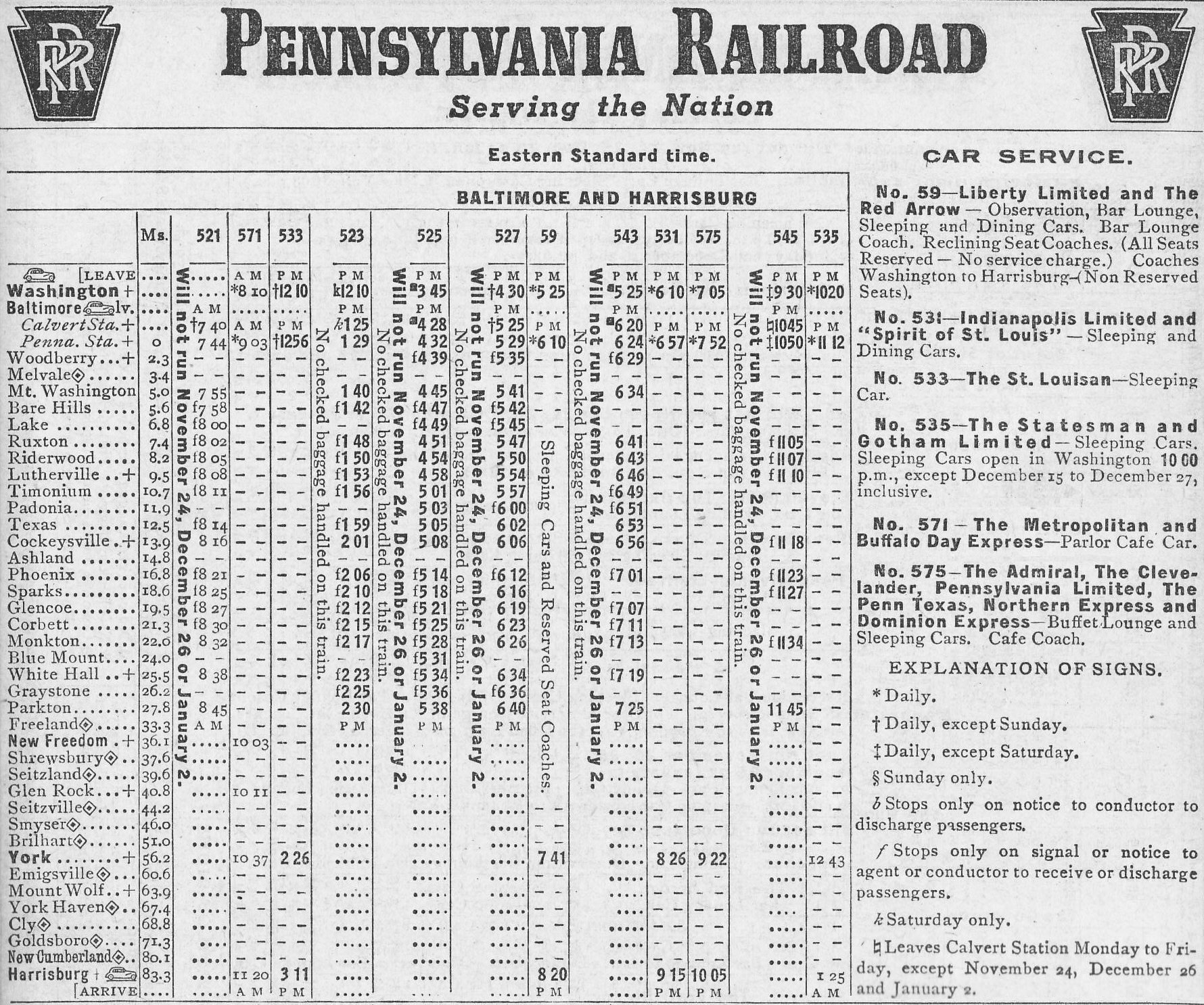

Northern Central Railway

One of the oldest railroads in the country operating 1828-1972, from

Baltimore, MD to York PA and later beyond to Harrisburg PA and north to Lake

Ontario.

Controlling interest acquired by Pennsylvania RR in 1861.

Major (and only) connection from Washington to the North and West during the

Civil War. (No bridges over the Susquehanna). York PA was the principal rail

link to the North.

Lincoln rode on NC RRY coming to Washington from Illinois,. changing stations

in disguise at night in Baltimore to avoid assassination.

He rode again going to and returning from Gettysburg in 1863, and in 1865 his

funeral cortege traversed the railway en route to Springfield IL.

Lincoln Cortege Picture (Wikipedia)

Baltimore was the 3rd largest city in US at time of Civil War.

Passenger service was terminated in 1957 and the line abandoned in 1972 after

hurricane Agnes destroyed many bridges.

Timetable NCRR 1957 (Wikipedia)

Pennsylvania portion was rebuilt for freight in 1985 by the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, later abandoned and leased out.

The line operated dinner trains and "murder mystery" trains as the "Liberty

Limited" from 1996 to 2001 until it was shut down by the refusal of the York

Borough Council to continue access to the city and continuing problems with the

Borough Council of New Freedom, PA for access to its terminus.

The line from Baltimore to York is now a bike trail, the Northern Central and

York County Heritage Trail.

Map of Bike Trail

Kieran responded the same day saying about White's translations:

". . .his "problem-solving" approach to translating Verne, his

straight-forward language transfer of Verne's French without the creative,

literary, and non-imitative embellishments of other translators such as Desages,

Towle, or Glencross."

And so the situation remained until 14 April 2008 when I wrote:

Kieran, hold your breath.

Last night at the prompting of your enquiries,

I did a little more searching on White, since it had been some time since I had

run a "google" search, and things do pop up . . . But the most

revealing was the "History of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company: with plan of

Organization", published by Henry T. Coates, 1895. On Page 52 of Volume II we

find the biography of Stephen W. White, and on page 51 we have a full page

spread of the photos of four people, one of whom is Stephen W. White.

Photo of Stephen W. White

White had emerged from the shades of history. From the biography in the

Pennsylvania Railroad History the following picture emerges:

Stephen W. White—biography

Born 16 July 1840 in Philadelphia

Educated in public schools of that

city

Entered Central High School February, 1854, from Jefferson Grammar

School

Graduated February, 1858, as Bachelor of Arts at the head of his

class

Later received the degree of Master of Arts from the High School

1858—1870 Shorthand clerk to the Treasurer of the American Sunday School

Union, assistant editor of Sunday School Times, and book-keeper to

several importing dry goods houses.

1870—1873 Private secretary (1 February 1870) to the great banker Jay Cooke,

and remaining with him until after the bankruptcy of the firm in the Panic of

1873.(18 September 1873).

1875—Entered railroad service as Assistant Secretary of the Northern Central

Railway, (a position he held until his retirement).

Later appointed to numerous boards of sections of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Active member of Associated Alumni of Central High School

Active churchman

in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania

Has published some excellent

translations from the German and the French

"His writings are all clean and terse, displaying careful study and

methodical arrangement, resultlants of his early training in stenography, in

which science he is not only an expert but an accomplished devotee (my

italics)."

From this we can draw the interesting conclusion that we owe his translations

to a financial disaster, the Panic of 1873. Stephen White was thus forced into

other activities than as secretary to a banker, and apparently started his own

business as a phonographer (short hand secretary) at 114 So. Third Street, which

led to his translating work for the Evening Telegraph with offices

nearby. He thus joins the ranks of Lewis Mercier, Mrs. Agnes Kinloch Kingston,

Agnes Dundas Kingston and Mrs. Frances Cashel-Hoey, who also entered the

translation business out of financial necessity. White apparently continued

translating even after joining the Railway, as Mysterious Island was not

published until 1876.

Picture of Stephen White Advertisement

On 15 April 2008 in an e-mail Kieran raised anew the question of how White

could have received an MA with only a high school education. The answer to this

question completes the story. Accidentally I had just purchased a biography of

Ignatius Donnelly (another favorite of mine—the Minnesota politician, orator,

populist, and promotor of the Atlantis myth). I knew that he came from

Philadelphia, and I wondered about his early education there. My wife asked me

if he had a college education. Imagine my surprise when I opened the book and

found the following sentence:

"Attending high school was undoubtedly the greatest single experience in

Donnelly's youth not only because it lifted him from the ranks of the average

citizen, but also because he studied at the Central High School. Directed by

Alexander D. Bache, later president of Girard College, it was superior to many

of the denominational colleges of the era, with a curriculum including

mathematics, physics, natural science, chemistry, French, Latin, Greek, and

drawing. When Bache went on to Girard College, John S. Hart assumed the

leadership of CHS. The institution had a reputation as an "immensely

aristocratic place where all the well-bred, patent-leathershod silver watch

boys" studied under "the most aristocratic individual in this country, not

excepting the President of the United States, John S. Hart, L.L.D."

"Edmund Spenser was Hart's favorite author; Donnelly's reading ranged from

Canterbury Tales to Richard Haklyut's Voyages. ..he (Donnelly) was unable to

master German syntax (showing that German was taught there as well), yet he read

the language well enough to have his set of Goethe rebound in expensive worked

covers when he left Philadelphia for the west."

Clearly this was no ordinary high school. Central High no doubt had a similar

effect on Stephen White. Another trip to Wikipedia revealed an article on the

history of Central High School, Philadelphia. There we learn that:

"Central High School holds the distinction of being the only high school in

the United States that has the authority, granted by an Act of Assembly in 1849,

to confer academic degrees upon its graduates. This practice is still in effect,

and graduates who meet the requirements are granted the Bachelor of Arts degree.

Central also confers high school diplomas upon graduates who do not meet the

requirement for a degree."

Notable alumni include Noam Chomsky (Nobel Prize), Bill Cosby (humorist),

Frank Stockton (writer), Douglas Feith (invasion of Iraq), Alexander Woolcott

(columnist, critic), and Jeremiah Wright (Obama's nemesis).

The mystery of the BA and MA are finally revealed! Also we learn that Hart

was president of the school from 1842-1858, during both persons' attendance.

Alexander Bache, the founder, (grandson of Benjamin Franklin), an astronomer,

was formerly a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and later head of the

U.S. Coast Survey and completed the mapping of the entire coastline of the

U.S.

In another visit to Wikipedia we also learn that there is a book, History

of Central High School, published by Lippincott in 1902 which has been

scanned by Google-books.

On p. 106 we have, repeated from "Alumni Notes of various alumni on Professor

Kirkpatrick":

"I would mention my indebtedness to the study of phonography, which we were

taught by Professor Kirkpatrick during the first two terms. He was very

successful in the imparting of a thorough knowledge of shorthand, and it has had

a very important bearing on the major portion of my business career."—Stephen

W. White

Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897) published the first edition of his shorthand

system of phonography in 1837. The system is somewhat akin to the Hebraic way of

writing in which only the consonants are written down and the vowels are

indicated by embellishments. The first dictionary of stenographic outlines was

produced from lithographic transfers written by the inventor in 1846 with the

following title: A Phonographic Dictionary of the English Language;

containing the most usual words to the number of twelve thousand. This only

eight years before White commenced the study of phonography, showing that he was

one of the early practitioners. Isaac Pitman & Sons, the Phonoographic

Depot, 2 West 45th St, New York City, published numerous reference

works and novels in shorthand script in the 19th century including

Sherlock Holmes, Dickens, and Around the World in Eighty Days by

Jules Verne (50 cents). In the Tenth International Contest, Atlantic City, NJ,

1914, a Pitman phonographer won the gold medal in the 280 wpm test with 98.6%

accuracy.

1916 Advertisement

Another Central High alumnus reminisces:

"I had taken private lessons in French from Professor Bregy before entering

the High School, and also from Professor H. Magnin, so that perhaps I had to

some extent advantages over some of my fellow-students. This, however, was not

the case with the German language, for there for the first time I was introduced

by Professor F. A. Roese to the beauties of the German language and literature.

I supplemented my lessons in German in the school by private lessons with

Professor Roese, which continued over a long period. I got to know him very

well, and found him to be a most cultivated and agreeable companion, and I

recall now with much pleasure the time spent with him in reading Schiller and

Goethe, to say nothing of some of the minor poets. Stephen W. White, of

the Thirty-first Class, was a student with me in these private lessons, and

was the most apt of any of us in acquiring the German

Language."

This completes our knowledge of Stephen W. White to date. Clearly not a hack

writer, he was a literate product of the American public schools capable of

comparison and perhaps superior to many of the translators employed by Sampson

Low in England. His training in phonography gave him an excellent ear for

languages, supplementing his academic achievements. Unfortunately we do not have

any indication of his other translations from the German, but at least he has

emerged as a real person, and no longer just a footnote in a library catalogue.

William Struthers the Poet and William Struthers the

Millionaire

William Struthers (October 14, 1854—1930+) was a minor poet from Philadelphia

in the latter part of the 19th century. He was the grandson of John Struthers

who emigrated from Scotland in 1816 and settled in Philadelphia where he set up

a marble cutting and architectural business. After his death in 1840 the

business was carried on by his son William Struthers (the poet’s uncle), later

operating as William Struthers and Sons. The firm was engaged in the erection of

hundreds of monuments and marble buildings throughout the 19th century, and was

awarded the largest contract, $5,000,000, that was ever awarded to any one firm

for the marble work of the "new" Philadelphia public buildings. After his death

in 1876 the business was conducted under the old title by his sons William

Struthers, Jr. (poet’s cousin, 15 June 1848—12 December 1911) and John Struthers

and then by the latter alone.

By the time he retired (sometime after 1876) William Struthers, Jr. had

become a millionaire. He spent time traveling in Europe (1888-1892) staying at

the Hotel Mirabeau in Paris, and was an early member (elected 20 May 1877) of

the "Jekyll Island Club" in Georgia, the subject of several current documentary

biographies. He resigned from the club after three years as he had not used it,

and then was re-elected a second time (13 November 1895) at the urging of his

friends and constructed a house "Moss Cottage" on Jekyll Island in 1896. He had

the distinction of being the first person to bring a motor car onto the island,

(the island is rather large) only to have it voted off because of the noise. In

1900 he was residing in Radnor, Delaware with four servants where he had a

summer house. He had one daughter, Jean (b. Aug, 1871), and he died on 12

December 1911 less than one month after his wife Savannah ("Vannie") (1849—23

Nov 1911).

Picture of Moss Cottage

But William Struthers the poet was not William Struthers the millionaire. The

child of a younger son of the founder of the Struthers empire, he was born into

more modest surroundings. His father was John S. Struthers (b. Jan 1827). At the

time of the 1860 census at age 34 he was living in Newark, New Jersey listing

his occupation as a Railroad Conductor, with his wife "Lizzie" (age 31) and four

children Helen (13), William (5), Mary (3) and Agnes (5 mo). By the time of the

1900 census John S. and his family were back in Philadelphia at #50

6th Street with his unmarried daughters Helen (53) and Agnes (39),

his son-in-law Edwin Ward (30), an attorney, his wife Mary (42) and William (the

poet, 45). At this time his father was listed as a "bank clerk", and William’s

occupation was listed as a "Musical Critic".

By the time of the 1930 census, Edwin Ward the attorney (50) was the head of

the household still supporting his in-laws William (74) and Agnes (66). The

house is listed at a value of $15,000, a significant sum at the time, and also

as "having a radio".

"William Struthers’ father (John S.) served in the Civil War, first as

captain in the Pennsylvania cavalry, and then as commander-in-chief of a

division of the ‘Dismounted Camp’ near Washington. While there he had his wife

and children with him; and thus young Struthers had an opportunity of studying

the poetical side of a soldier’s camp life", later described in his poems.

William was not a healthy child and was educated privately. "Although he

managed to weather through to manhood, it was with the struggle of an invalid,

too powerless even now (1890) to raise his voice above a whisper . Yet he is an

accomplished scholar and linguist. Various translations of his, prose from the

French and Italian, verse from the Spanish, have appeared in the leading

magazines and newspapers; while as a writer of original verse, his pleasing

poems, sonnets, rondeaus, etc., have made his name familiar."

William, a son in a prominent family, would have been well known to Stephen

White, who was fourteen years his senior, and undoubtedly the latter appreciated

his literary abilities. The "Struthers" family in 1870 would be as well known in

Philadelphia as the "Kennedys" are today. Engaged in a lengthy translation

himself, White probably welcomed the opportunity of offering to Struthers the

translation of the short piece A Winter's Sojourn in the Ice. White no

doubt knew of William’s infirmities, and was doing the family a favor. Also the

association of the Struthers name with a translation could only help both

White’s business and the reputation of the Evening Telegraph. Thus this

little piece is the only translation of Verne known to date done by a Victorian

poet.

Struthers published his poems in literary magazines mostly in the 1890's. He

wrote mainly sonnets, a verse form not the easiest in which to compose. Several

books of his poems have been published:

Transcriptions from Art and Nature, 96 p., Philadelphia, London: Drexel

Biddle, 1902

Lyric Moods and Tenses, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1910

Rythmic Soliloquies, Philadelphia: Wm. F. Fell, 1910 (reprinted in part

from various periodicals)

The following is perhaps a typical sample of his poetry:

Walt Whitman, 1901

William Struthers, from the Conservator

The paling stars proclaimed another day—

He fell asleep when in the

century's skies

With smiling lips and trustful, dauntless eyes;

He.

genial still, amidst the chill and gray,

He. the Columbus of a vast emprise,

Whose realization in the future lay:

He. who stepped from the well-worn,

narrow way

To walk with Poetry in larger guise.

The years announce him

in a new born age;

And fortunate, despite of transient griefs,

The ship

of his fair fame, past crags and reefs,

Sails bravely on. and less and less

the rage

Of gainsaying winds becomes; while to his phrase

The world each day gives

ampler heed and praise!

From: Current Literature A Magazine Of Record And Review Vol. XXXI,

July-December, New York: Current Literature Publishing Co., 1901

One may question whether the 20 year old invalid was indeed capable of this

translation (as I did at first), but unless another William Struthers is found,

of the current period, in Philadelphia, (and none seem to appear in the census)

with a literary background and knowledge of three languages, I believe we must

accept the fact that William Struthers, the poet, has indeed translated Jules

Verne.

Note: All quoted materials available on Google-Books.