Part 3 —

Christian Responses

113

Feminist theology

Christ,

cosmos and the human condition, according to feminist theologians

Karen Campbell-NeIson

Karen

Campbell-Nelson presented this paper to the WSCF Asia-Pacific regional women's meeting

in Singapore in June 1985.

There

are a number of difficulties in giving a presentation on feminist » theology.

One is knowing where to begin, because there are so

many issues that demand our attention and reflection. And because there is such

a wide range of feminist theologies — some Christian, some not — one author

alone cannot be representative. What I have chosen to do, since this is

intended to be an introduction, is to give a brief overview of one woman's

feminist theology, which can help us see what is new and different about

theology done from a Christian feminist perspective. The feminist I have chosen

is Rosemary Radford Ruether, because she has been a

formative influence on my own approach to theology, and I feel comfortable

discussing her theology. She is also one of the more systematic

feminist theologians — she looks at traditional theological categories (such as

creation, sin, salvation), but from a radically different starting point. By

examining a few of these categories and comparing some traditional male views

with those of Ruether, it will be easier, I hope, to familiarise ourselves with the concerns and insights of

feminist theology. I have taken some of the main points from Ruether's article "Feminist Theology and

Spirituality," in an anthology of feminist writings entitled Christian

feminism: visions of a new humanity1. This, in turn, is a

synopsis of some of the major points in Ruether's Sexism

and god-talk: toward a feminist theology2.

Before

continuing, let me add that, as do most published feminist theologians to date Ruether writes from the perspective of a white, well

educated, middle class woman. It is certainly relevant to ask what value this

may have for women living in the overwhelmingly poor, non-white countries of Asia.

I believe it is relevant for all women interested in theology to be acquainted

with the theological reflections of their feminist sisters, whoever and

wherever they are, for that is one way in which bridges of solidarity can be

formed. But I also believe that each of these same women has a responsibility

to engage in her own theological reflection — to give theological meaning to

her experiences. In this way our bridges of understanding can reach further

114

115

and become stronger.

Thus I hope that a brief introduction to Ruether's

theology will help us see our potential, as feminists, to transform and humanise

traditional theology. There are several good points that Ruether

makes in her agenda for feminist theology. Feminist theology should:

Be

"a critique of the sexist bias of theology itself

Construct

a new base from which to theologise (making use of

alternative traditions, discovering new theological methods, etc)

Help us

experience the Divine in new places and ways

Be

engaged in the search for a mature and responsible humanity. Perhaps above all

else, Ruether stresses the validity of women's

experiences as a starting point for theology. For too long, women's experiences

have been completely ignored by theologians — to the point that their

theologies exclude women. It is time women claimed a right to theologise based on our own understanding and experience of

the Divine.

Language for Cod

Although

many traditional theologies claim that language for God is simply metaphorical

and not to be taken literally, God is almost exclusively referred to in male

terms. The image of God as a great patriarch is so prevalent that males have

become the normative representatives of God. But there is no justifiable reason

why males should have priority in our language of God. Also, we need to use

language other than names for parents (God as Mother, Father or Parent) so that

we do not always put ourselves in the position of being dependent children.

There are other ways of relating to God which have their own appropriate

metaphors: Holy Wisdom, Divine Healer, Liberator, Guide and Comforter,

that can help us establish images for the Holy One.

Cosmology (study of the

cosmos)

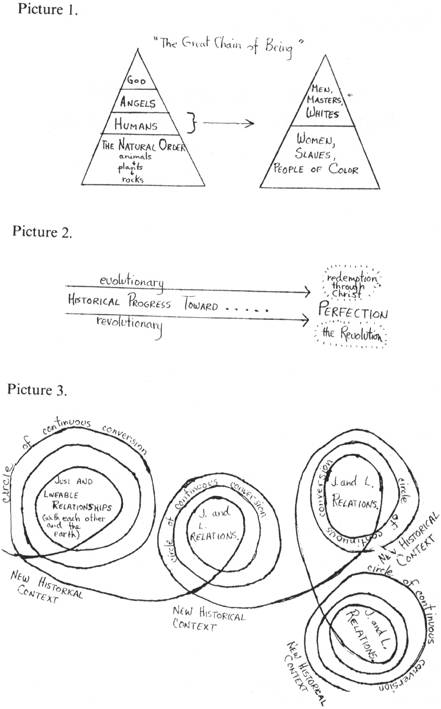

There

are a couple of different ways of depicting patterns of history and social

orders. One model is a pyramid with God on top, followed by angels, humans, and

the "natural order". The human layer of this pyramid is, in turn, characterised as a pyramid, so that the social

"order" mirrors the divine "order", with men, masters, and

whites ruling over women, slaves, and people of color (see picture 1). What is

best and desirable in this world will "trickle down" from the upper

to the lower layers of the pyramids.

Another

model focuses more specifically on historical movement, assumed in this case to

be a straight line headed toward perfection — that is, history is inherently

progressive. There are two ways to think of this historical spectrum. Ruether calls one "evolutionary" — this view is

held by those who see historical progress culminate in Christ, and in the

redemption available through the event of his life. The other Ruether calls "revolutionary" — historical

progress towards perfection culminates in revolution (see picture 2). In both

instances there are favoured agents in this so-called

progress of history: white, Christian males (all others fall somewhere behind

them on the historical jet to perfection).

For

feminists, it is difficult to accept these models. Women do not need men to rule

over them any more than nature needs humans to rule over it. The "Great

Chain of Being" fosters relationships of exploitation, not of love and

116

care. As for the second

model, a linear model of history moving towards the perfect is unacceptable precisely

because of the fact that men define and control this "perfection". Ruether has formulated an alternative model of cosmology as

a response to these criticisms. According to her, there are processes inherent

in nature that can continually renew life. However, these processes have been

disrupted because we have used our gift of intelligence to exploit, rather than

to serve others and the earth. We have sinned. Ruether

believes that, through different historical contexts, humanity can follow

circles of continuous conversion that will draw it back to centres of just and

"liveable" relationships (see picture 3).

Christology (study of

Christ)

What is

important about Christ is the incarnation, and what is important about the

incarnation is that God became human. So often, in traditional theology, Jesus'

gender is used to suggest that "maleness is more appropriate to God than

femaleness". Indeed, this is basically the theological argument adopted by

the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic and other churches in their refusal to

ordain women.

But, as

Ruether asserts: "The historical accidents of

Jesus' person — maleness, Jewishness, social class — do

not suggest that God is more incarnate into these particularities than into

others". Rather, the fact of the incarnation encompasses humans of all

races and genders. Christ is not a justification for existing

patriarchal or hierarchical social structures, but rather someone after whom we

can pattern ourselves in order to create a new and liberated humanity. And

here, no doubt, Ruether must sound a bit heretical to

many "recognised" theologians, for she

claims that Jesus as a past, historical person is not the only model we have

for Christ. Jesus did not proclaim himself but rather a future of

liberated humanity, and because he was faithful to this vision of God's

will he must indeed be considered Christ. But we too are called to that vision

and have a responsibility to recognise other models

of Christ in our midst, in this day and age.

Anthropology (study of humanity)

As with

cosmology, there are two traditional models — in this case, they explain the

relationship betwen men and women. The

first model, popular before the eighteenth century in Europe, is a hierarchical

model not unlike the human pyramid in picture 1. In this model, males

have the best qualities of both mind and spirit while females are viewed as

servants and the followers of male leaders. Around the start of the eighteenth

century, there was a gradual shift in the means of production in Europe. The

home became no longer the main centre of production; women, who remained in the

home, acquired new, more specifically domestic, roles. At the same time,

religion became more of a private matter. Thus, another model: one which Ruether calls the com- plementarity

model. Under this model, men and women have distinct personal characteristics

and distinct spheres of influence which complement one another. Whereas men are

more aggressive, egoistic, materialistic, rational, and secular; women are more

passive, altruistic, self-sacrificing, nurturing, and religious. In such a

model it is only fitting, then, that men have

117

responsibility in the

"real" world of work outside the home and women are considered best

suited to keep the home fires burning. This model further suggests that man and

woman can most ideally complement one another when they are joined in that

perfect union of holy matrimony.

Ruether doesn't introduce her own model, but criticises these two, as well as another model promoted by

radical feminists. This is the complementarity model

turned inside out so that it becomes a model of opposition between men and

women. Radical feminists often mistakenly claim (or at least give the

impression that they claim) that women are morally superior to men. Women tend

to be naturally good and integrated human beings; men tend to be naturally evil

and schizophrenic, not having resolved the dualisms in their lives.

Although

Ruether recognises that, by

being excluded from power structures, woman has been forced to develop

"those qualities that are necessary, not only to balance, but to transform

the distorted tendencies that appear in those who exercise power," she is

quite careful not to idealise woman. She stresses

that both men and women sin and are in need of redemption.

Redemption (salvation)

Not

only does the orthodox Christian tradition conceive of the redeemer as

normatively male; it regards redemption as a repudiation of the

"lower" sphere (in which sex, a "base desire", and the female

body play a prominent role). In this form of redemption sexuality disappears.

But Ruether affirms the goodness of sexuality and

rejects a definition of redemption that calls for personal conversion. As long

as sin and salvation only deal with private matters, structures of injustice

will continue unchecked.

Ruether defines redemption as the quest for the

good self that must go hand in hand with the quest for the good society

— the two cannot be separated. So, for example, in the quest for the good society

we seek ways by which ownership and management of work are in the hands of the

workers. But we must also recognise that these

workers must have more than their own self-interests at heart if justice is to

be realised. Redemption demands conversion at both

the social and personal levels.

These,

then, are a few examples of how one feminist has rethought traditional

theological categories in such a way as to redefine women — as no longer

marginal and passive subjects of theology, but active agents of it. It is

through such active engagement that we, too, can transform theological agendae of the future.

Notes

1. WEIDMAN, Judith L.

(ed), Christian feminism: visions of a new

humanity. Harper and Row, New York, 1984

2. RUETHER,

Rosemary R., Sexism and God-talk: toward a feminist theology. Beacon

Press, Boston, 1983.