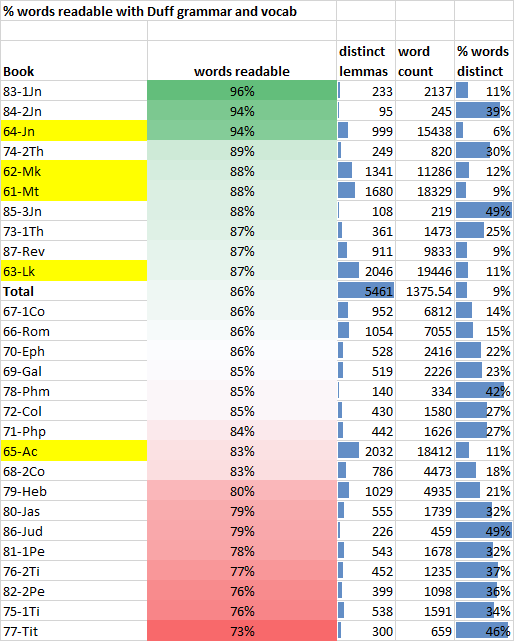

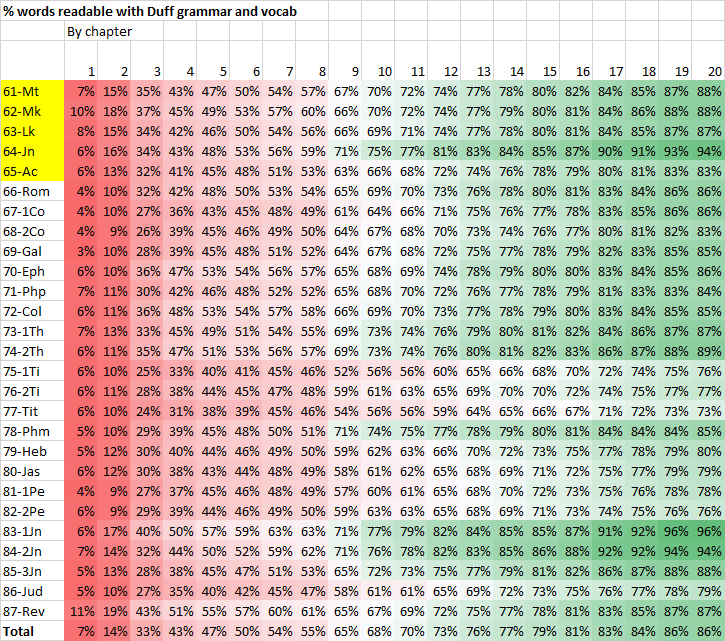

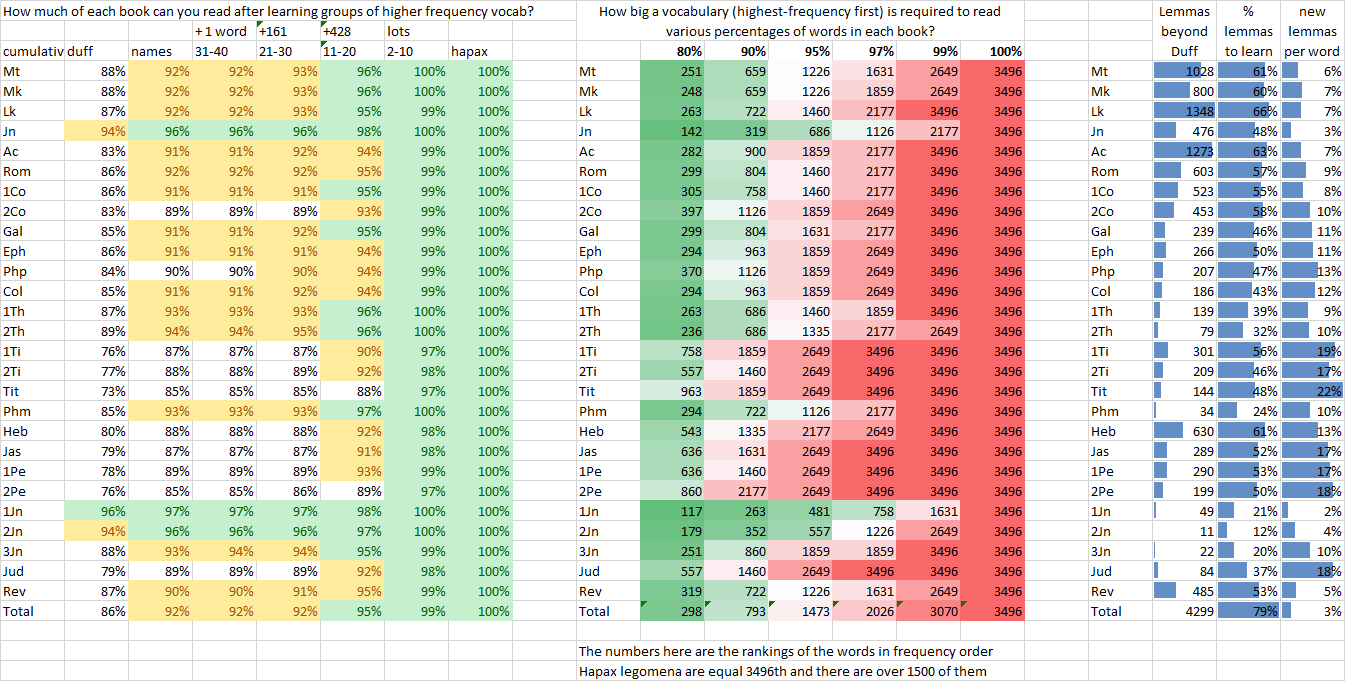

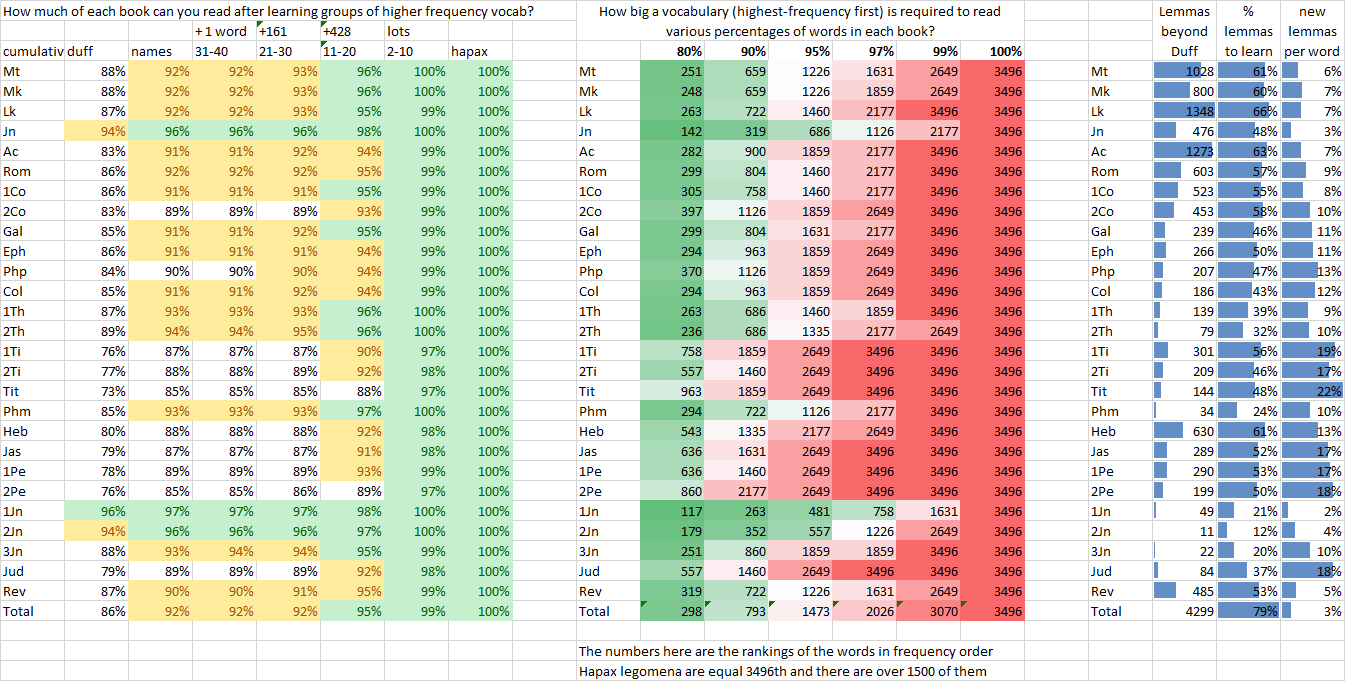

Here are some more stats, which I think give a more sensitive view of the issue. For the second two tables, I've assumed proper nouns don't need to be learned. Duff provides the first 600 or so most-frequent words, down to 30 occurrences.

I came across a similar observation in David Bentley Hart's preface to his new translation; he makes a similar observation, attributing it to the John's own limited command of Greek:

Even the Gospel of John, perhaps the most structurally and symbolically sophisticated religious text to have come down to us from late antiquity, is written in a Greek that is grammatically correct but syntactically almost childish (or perhaps I should say, "remarkably limpid"), and -- unless its author was some late first-century precursor of Gertrude Stein -- its stylistic limitations suggest an author whose command of the language did not exceed mere functional competence.

I'm no authority in any of this, but I'm skeptical of Hart's hypothesis. In my experience, language skill adequate to produce a grammatically correct 15,000 word narrative tends to come with a vocabulary beyond that of a native two-year-old.

On Titus, the figure I got was 144 new words to learn, in the 659 word letter. It seems much harder to me (beginner-intermediate) than Matthew or Luke. Even though there are far fewer words to learn, they're concentrated in a small text, so that instead of 6-7% of words being new, it's 22%. A 15-word sentence has 3 unknown words instead of 1. I think the 95% rule is a helpful one.