Local authorities under the Beejapoor government, in the immediate neighbourhood of Sivajee – The Sawunts of Waree – The Seedee of Jinjeera – A daring robbery – Forts taken by surprise – The province of Kallian reduced – Shahjee seized – Sivajee applies to Shah Jehan for his enlargement – An attempt to seize Sivajee frustrated – Shahjee released, – returns to the Carnatic; – his eldest son Sumbhajee killed – Progress of Sivajee – Murder of the Raja of Jowlee, and conquest of his country – Rohira escaladed – Pertabgurh built – Shamraje Punt the first Mahratta Peishwa – Sivajee’s views on the Moghul districts – History of the Moghuls in the Deccan since 1636 – Meer Joomleh – Moghuls attack Golcondah; – make war on Beejapoor – Shah Jehan’s illness, – his four sons, – all aspire to the crown – Aurungzebe’s character and progress; – usurps the throne.

The details contained in the foregoing chapters, have probably enabled the reader to form a sufficiently clear idea of the state of the Deccan, so far as relates to the different great powers which divided it; but, for the sake of perspicuity in what follows, it is necessary to offer a few remarks respecting the various local authorities under the Beejapoor government, in the immediate neighbourhood of the tract occupied by Sivajee.

The south bank of the Neera, as far east as Seerwul, and as far south as the range of hills north of the Kistna, was farmed by the hereditary Deshmookh of Hurdus Mawul, named Bandal; and the fort of Rohira was committed to

his care. Having early entertained a jealousy of Sivajee, he kept up a strong garrison, and carefully watched the country adjoining Poorundhur. The Deshmookh was a Mahratta, but the Deshpandya was a Purbhoo (or Purvoe), a tribe of the Shunkerjatee, to whom Sivajee was always partial.

Waee was the station of a Mokassadar of government who had charge of Pandoogurh, Kummulgurh, and several other forts in that neighbourhood.

Chunder Rao Moray, Raja of Jowlee, was in possession of the Ghaut–Mahta from the Kistna to the Warna.

The Kolapoor district, with the strong fort of Panalla, was under a Mahomedan officer appointed by government.

The ancient possessions of the Beejapoor state in the Concan, were held in Jagheer, or farmed to the hereditary Deshmookhs, with the exception of the sea ports of Dabul, Anjenweel, Ratnaguiry, and Rajapoor, which, with their dependent districts, were held by government officers. The principal hereditary chiefs were the Sawunts of Waree; they were Deshmookhs and Jagheerdars of the strong tract adjoining the Portuguese territory at Goa, and their harbours were the resort of pirates, early known by the name of Koolees. Next in consequence to the Sawunts, were the Dulweys of Sringarpoor, who, from occupying an unfrequented tract, were, like the Raja of Jowlee, nearly independent.

The province of Kalliannee, formerly belonging to the kings of Ahmednugur, and ceded to Beejapoor by the treaty of 1636, was principally confided

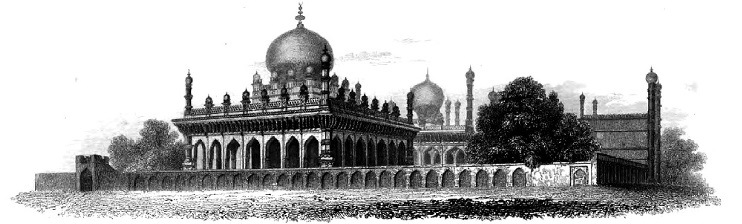

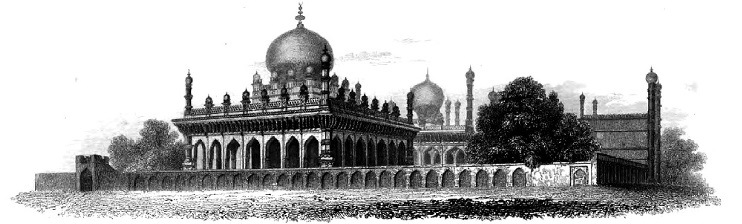

to two authorities; the northern part of it, extending from Bheemree (or Bhewndy) to Nagotna (or Nagathanna) was under a respectable Mahomedan officer appointed by the king, and stationed at the town of Kallian Bheemree. He had an extensive charge, comprehending several strong forts both above and below the Ghauts; but these forts, from the causes we have endeavoured to explain, were much neglected. The southern part of the province was held in Jagheer, by an Abyssinian141; the condition of his tenure, as far as can be ascertained, was the maintenance of a marine for the protection of the trade, and conveying pilgrims to the Red Sea. His possessions were not considered hereditary, but were conferred on the most deserving Abyssinian officer of the fleet, and the chief so selected was styled Wuzeer. The crews of his vessels were in part composed of his countrymen; and a small African colony was thus formed in the Concan. The great maritime depôt was the harbour of Dhunda Rajepoor, in the middle of which stands the small fortified island of Jinjeera142. In the vulgar language of the Deccan, all natives of Africa are termed Seedees. The name of the principal Abyssinian, at this time, was Futih Khan,

commonly styled the Seedee143, an appellation assumed by the chief and his successors, by which they have been best known to Europeans. The Seedee had charge of several forts, amongst which were Tala, Gossala, and Rairee; they were all intrusted to the care of Mahrattas144.

Thus much being premised, we return to Sivajee, who was secretly, but actively, employed in very extensive plans, in prosecution of which, he was himself busy in collecting and arming Mawulees, whilst some of his Bramins were detached into the Concan, to gain intelligence and forward his views in that quarter.

Having heard that a large treasure was forwarded to court by Moolana Ahmed, governor of Kallian, Sivajee put himself at the head of three hundred horse, taken at Sopa, now mounted with Bargeers on whom he could depend, and, accompanied by a party of Mawulees, he attacked and dispersed the escort, divided the treasure amongst the horsemen, and conveyed it with all expedition to Rajgurh. This daring robbery completely unmasked his designs; but the news had scarcely reached the capital, before it was known that Sivajee had surprised and taken the forts of Kangooree, Toong, Tikona, Bhoorup, Koaree, Loghur,

and Rajmachee145. Tala, Gossala, and the strong hill of Rairee, were given up to his emissaries: several rich towns were plundered in the Concan; and the booty with great regularity conveyed by the Mawulees to Rajgurh.

But this was not the extent of his designs; or of his success. Abajee Sonedeo, one of the Bramins, educated by Dadajee Konedeo, who had already distinguished himself as much by his boldness as by his address, pushed on to Kallian, surprised the governor, took him prisoner, and procured the surrender of all the forts in that quarter.

As soon as Sivajee received this joyful intelligence, which exceeded his expectations, he hastened to Kallian, and, bestowing the highest encomium on Abajee Sonedeo, appointed him Soobehdar, or governor of the country comprised in this important

acquisition. No time was lost in commencing revenue arrangements. Ancient institutions were revived wherever a trace of them could be found; and all endowments to temples, or assignments to Bramins were carefully restored or maintained. As the Seedee was a formidable neighbour, Sivajee, to secure the hold already obtained on his Jagheer, gave orders for building two forts, Beerwaree, near Gossala, and Linganah, near Rairee.

Moolana Ahmed, made prisoner by Abajee Sonedeo, was treated by Sivajee with the utmost respect; and, being honourably dismissed, he returned to court. The news of his capture, and the surrender of the forts, had arrived before him, and although permitted to pay his respects to the king, he was not reinstated in any place of trust or emolument.

Sivajee’s rebellion, in consequence of the report of Moolana Ahmed, began to create general anxiety at Beejapoor; but Mohummud Adil Shah, impressed with an idea of its being secretly incited by Shahjee, took no active measures to suppress it by force. The power of Shahjee in the Carnatic, which had greatly increased by his being left as provincial governor, on the return of Rendoollah Khan to court, may have tended to occasion such a suspicion, strengthened also by the circumstance of its having begun in his Jagheer, and spread over a province where his power had so lately been suppressed146.

The king, therefore, sent private orders to Bajee Ghorepuray of Moodhole, then serving in the same

part of the country with Shahjee, to seize and confine him. This object Ghorepuray effected by treachery: he invited Shahjee to an entertainment, and made him prisoner.

On being brought to court, Shahjee was urged to suppress his son’s rebellion; for which purpose freedom of correspondence was allowed between them. Shahjee persisted in declaring that he was unconnected with his son; that Sivajee was as much in rebellion against him as against the king’s government; and recommended his being reduced to obedience by force of arms. Nothing he urged could convince Mohummud Adil Shah of his innocence; and, being enraged at his supposed contumacy, he ordered Shahjee to be confined in a stone dungeon, the door of which was built up, except a small opening; and he was told, that if within a certain period his son did not submit, the aperture should be forever closed.

Sivajee, when he heard of the imprisonment and danger which threatened his father, is said to have entertained thoughts of submitting; but if he ever seriously intended to adopt such a plan, it was overruled by the opinion of his wife, Suhyee Bye, who represented that he had a better chance of effecting Shahjee’s liberty by maintaining his present power, than by trusting to the mercy of a government notoriously treacherous147.

The alternative which Sivajee adopted, developes a principal feature of his early policy. He had

hitherto carefully refrained from molesting the subjects or territory of the emperor, probably from an opinion of the great power of the Moghuls, and from a design he appears to have contemplated, of throwing himself on the imperial protection in case of being pushed to extremity by the government of Beejapoor.

He accordingly, at this time, entered into correspondence with Shah Jehan, for the purpose of procuring his father’s enlargement. The proposals made by Sivajee are not known, but the emperor agreed to forgive the former misconduct of Shahjee, to admit him into the imperial service, and to give Sivajee a munsub of five thousand horse148.

It is probable that the emperor’s influence, and the friendship of Morar Punt149, were the means of saving Shahjee from a cruel death. He was released from his dungeon on giving security; but he was kept a prisoner at large, in Beejapoor, for four years150.

Sivajee, whose immediate object was effected by his father’s reprieve, artfully contrived to keep his proposal of entering the Moghul service in an unsettled state, by preferring a claim on the part of his father, or himself, to the Deshmookhs’ dues in the Joonere and Ahmednugur

districts, to which he pretended they had an hereditary right. Sivajee’s agent, who went to Agra with this ostensible purpose, did not, as was probably foreseen, succeed in obtaining a promise of the Deshmookhee; but he brought back a letter from Shah Jehan, promising that the claim should be taken into consideration upon Sivajee’s arrival at court151.

During the four years Shahjee was detained at Beejapoor, Sivajee, apprehensive, perhaps, for his father’s safety, committed few aggressions, and the king was, probably, deterred from sending a force against him, lest it should induce Sivajee to give up the country to the Moghuls, which the emperor had sufficient excuse for receiving, on account of arrears of tribute. In this interval, a feeble attempt was made to seize Sivajee’s person. It was undertaken by a Hindoo named Bajee Shamraje. Sivajee frequently resided at the town of Mhar in the Concan; and the party of Shamraje, passing through the territory of Chunder Rao Moray, lurked about the Phar Ghaut until an opportunity should offer; but Sivajee anticipated the surprise, attacked the party, near the bottom of the Ghaut, and drove them in great panic to seek safety in the jungles152.

Shahjee had, in vain, endeavoured by every means to obtain permission to return to his Jagheer in the Carnatic, when, at last, the great disturbances which became prevalent in that quarter, induced the king to listen to recommendations in his favour. Previously, however, to granting his complete enlargement, Shahjee was bound down by solemn engagements to refrain from molesting the Jagheerdar of Moodhole; and, in order to induce both parties to bury what had passed in oblivion, Mohummud Adil Shah made them exchange their hereditary rights and enams as Deshmookhs, Shahjee giving those he had received in the districts of Kurar, and Bajee Ghorepuray what he possessed in the Carnatic153.

This agreement, however, was not acted upon; and the first use Shahjee made of his liberty was to write to Sivajee, “If you are my son, punish Bajee Ghorepuray of Moodhole;” an emphatic injunction to vengeance, which Sivajee, at a fit time, carried into terrible execution.

On his return to the Carnatic, Shahjee found that the accounts of the disturbed state of the country were not exaggerated; every petty chief endeavoured to strengthen himself, and weaken his neighbour, by plunder and exaction. His own Jagheer had been subject to depredations; and he sent his eldest son Sumbhajee to punish one of these aggressions on the part of

the Killidar of Kanikgeeree. On this service Sumbhajee was killed, and his detachment defeated. Shahjee afterwards took Kanikgeeree by assault, and avenged his death; but the loss of Sumbhajee was a source of much affliction; and the event was followed by the demise of his principal agent in the Carnatic, Naroo Punt Hunwuntay, a Bramin, educated in the school of Mullik Umber, who had served Shahjee for many years. His place was fortunately well supplied by his son, Rugonath Narrain, a person of considerable talent, whom we shall have occasion to notice at a future period. Disturbances became more and more prevalent in the Carnatic, and quite diverted the attention of the Beejapoor government from Sivajee; but no sooner was his father released, than he began to devise new schemes for possessing himself of the whole Ghaut–Mahta, and the remainder of the Concan.

He had, in vain, attempted to induce the Raja of Jowlee to unite with him against the Beejapoor government; Chunder Rao, although he carried on no war against Sivajee, and received all his messengers with civility, refused to join in rebellion against the king. The permission granted to Shamraje’s party to pass through his country, and the aid which he was said to have given him, afforded Sivajee excuse for hostility; but the Raja was too powerful to be openly attacked with any certain prospect of success; he had a strong body of infantry, of nearly the same description as Sivajee’s Mawulees; his two sons, his brother, and his minister, Himmut Rao, were

all esteemed good soldiers; nor did there appear any means by which Sivajee could create a division among them.

Under these circumstances, Sivajee, who had held his troops in a state of preparation for some time, sent two agents, a Bramin and a Mahratta, the former named Ragoo Bullal, the latter Sumbhajee Cowajee, for the purpose of gaining correct intelligence of the situation and strength of the principal places, but ostensibly with a design of contracting a marriage between Sivajee and the daughter of Chunder Rao.

Ragoo Bullal, with his companion, proceeded to Jowlee, attended by twenty five Mawulees. They were courteously received, and had several interviews with Chunder Rao, the particulars of which are not mentioned, but Ragoo Bullal seeing the Raja totally off his guard, formed the detestible plan of assassinating him and his brother, to which Sumbhajee Cowajee readily acceded. He wrote to Sivajee communicating his intention, which was approved, and in order to support it, troops were secretly sent up the Ghauts, whilst Sivajee, pretending to be otherwise engaged, proceeded from Rajgurh to Poorundhur. From the latter place he made a night-march to Mahabyllisur, at the source of the Kistna, where he joined his troops assembled in the neighbouring jungles. Ragoo Bullal, on finding that the preparations were completed, took an opportunity of demanding a private conference with the Raja and his brother, when he stabbed the former to the heart, and the latter was despatched by Sumbhajee Cowajee. Their attendants

being previously ready, the assassins instantly fled, and darting into the thick jungles, which every where surrounded the place, they soon met Sivajee, who, according to appointment, was advancing to their support.

Before the consternation caused by this atrocious deed had subsided, Jowlee was attacked on all sides; but the troops headed by the Raja’s sons and Himmut Rao, notwithstanding the surprise, made a brave resistance until Himmut Rao fell, and the sons were made prisoners.

Sivajee lost no time in securing the possessions of the late Chunder Rao, which was effected in a very short period. The capture of the strong fort of Wassota154, and the submission of Sewtur Khora, completed the conquest of Jowlee.

The sons of Chunder Rao, who remained prisoners, were subsequently condemned to death, for maintaining a secret correspondence with the Beejapoor government; but the date of their execution has not been satisfactorily ascertained. Sivajee followed up this conquest by surprising Rohira, which he escaladed in the night, at the head of his Mawulees; Bandal, the Deshmookh, who was in the fort at the time, stood to his arms on the first moment of alarm; and although greatly outnumbered, his men did not submit until he was killed. At the head of them was Bajee Purvoe, the Deshpandya; Sivajee treated him with generosity, received him with great kindness, and confirmed him in all his hereditary possessions. He had relations

with Sivajee, and afterwards agreed to follow the fortunes of his conqueror; the command of a considerable body of infantry was conferred upon him; and he maintained his character for bravery and fidelity to the last.

To secure access to his possessions on the banks of the Neera and Quyna, and to strengthen the defences of the Phar Ghaut, Sivajee pitched upon a high rock, near the source of the Kistna, on which he resolved to erect another fort. The execution of the design was intrusted to a Deshist Bramin, named Moro Trimmul Pingley, who had been appointed a short time before, to command the fort of Poorundhur. This man, when very young, accompanied his father, then in the service of Shahjee, to the Carnatic, whence he returned to the Mahratta country about the year 1653, and shortly after joined Sivajee. The able manner in which he executed everything intrusted to him, soon gained him the confidence of his master, and the erection of Pertabgurh, the name given to the new fort, confirmed the favourable opinion entertained of him.

The principal minister of Sivajee, at this period, was a Bramin, named Shamraje Punt, whom he now dignified with the title of Peishwa; and, as is common amongst Mahrattas, with persons filling such a high civil station, he likewise held a considerable military command.

Hitherto, Sivajee had confined his usurpations and ravages to the Beejapoor territory; but become more daring by impunity, and invited by circumstances, he ventured

to depart from his original policy, and to extend his depredations to the imperial districts. To explain the motives which actuated him, we must revert to the proceedings of the Moghuls.

Since the peace of 1636, they had held undisturbed possession of their conquests in the Deccan, and had been laudably employed in improving these acquisitions.

The prince Aurungzebe, after an expedition against Kandahar, was appointed viceroy of the Deccan for the second time in the year 1650, and for several years abated nothing of the active measures which had been adopted for fixing equitable assessments, and affording protection to travellers and merchants. He established the seat of government at Mullik Umber’s town of Khirkee, which, after his own name, he called, Aurungabad155. But, however capable of civil government, Aurungzebe was early habituated to the interest which is generally excited in the human mind by having once acted as a leader in war;

and in the year 1655, he readily seized an opportunity of fomenting dissensions at the neighbouring court of Golcondah, with the hope of involving the emperor in the dispute. At this period, the prime minister of Kootub Shah was the celebrated Meer Joomleh; he had attained that situation by his ability and his wealth; but he had considerable influence, and was held in very general esteem at every Mahomedan court in Asia. He was originally a diamond

merchant, and his occupation brought him acquainted with princes and their countries. His talents, his riches, and the extent of his dealings; had made him familiarly known at the imperial court, long before he rose to be vizier at Golcondah.

His son, Mohummud Amin, was dissolute, but he possessed his father’s confidence. This youth; having been guilty of some disrespect to the person, or authority of Abdoollah Kootub Shah, the latter thought fit to punish him. This treatment being resented by Meer Joomleh, altercation arose between him and the king, which, at length, led to a formal petition, on the part of the former, for the emperor’s protection. The application being warmly seconded by Aurungzebe, laid the foundation of that friendship between him and Meer Joomleh, which greatly contributed to Aurungzebe’s elevation.

Shah Jehan espoused the cause of Meer Joomleh as ardently as Aurungzebe could have desired, and addressed an imperious letter to Kootub Shah on the subject. The king, exasperated by this interference, threw Mohummud Amin into prison, and sequestrated his father’s property. Such a proceeding, exaggerated by the colouring which Aurungzebe gave to it, could not fail to rouse the anger of Shah Jehan, and he immediately determined on enforcing compliance with the orders he had sent in favour of Meer Joomleh. A choleric despot is prompt in his commands: Aurungzebe was ordered to prepare his army, to demand the release of Mohummud Amin, and satisfaction to

Meer Joomleh. In case of refusal, he was directed to invade the territory of Golcondah.

As the king would not acknowledge the emperor’s right of interference, Aurungzebe, on his rejecting the mandate; without any declaration of war, sent forward his eldest son, Sultan Mohummud, with a considerable force, on pretence of passing Hyderabad, on the route to Bengal, whither it was given out, he was proceeding to espouse his cousin the daughter of Sultan Shuja. Aurungzebe followed with the main army.

Abdoollah Kootub Shah did not discover the artifice until the young prince appeared as an enemy at his gates; when he solicited succour from his neighbours; and made concessions to the Moghuls, in the same breath. The citadel was attacked, and the town of Hyderabad plundered of great riches; the advancing succours were intercepted, and the king reduced to the greatest distress.

Shah Jehan, the first ebullition of his anger being subsided, began to repent of his hasty orders. Fresh instructions were despatched to Aurungzebe, desiring him to accept of reasonable concessions from Abdoollah Kootub Shah, and not to proceed to extremities; but Aurungzebe would not relinquish the advantage which his successful surprise had established, until he had extorted the most humiliating submission.

The king of Golcondah had, in the first instance, on the prince’s arrival, released Mohummud Amin, and restored his father’s property. He was now compelled to give his daughter in marriage to Sultan Mohummud, and to pay up all arrears

of tribute, fixed by Aurungzebe, at the annual sum of one crore of rupees; but Shah Jehan, in confirming these proceedings, remitted twenty lacks of the amount.

Meer Joomleh and Aurungzebe concurred in their ideas of the facility and expediency of reducing the kingdoms of Beejapoor and Golcondah into provinces of the Moghul empire, and of spreading their conquests over the whole peninsula; but Aurungzebe pretended to be actuated more by the hope of propagating the Mahomedan faith in that region of idolatry, than swayed by a desire of possessing its resources. Meer Joomleh having been invited to the imperial court, was shortly after raised to the rank of vizier, and took every opportunity of urging the fitness of a plan, in which both he and Aurungzebe, probably calculated their own future advantage. A very short period had elapsed when an event occurred, which drew the emperor partially to accede to their schemes of conquest, and induced him to authorise a war. This was the death of Mohummud Adil Shah, who, after a lingering illness, expired at Beejapoor, 4th November, 1656156.

The deceased king, although his tribute was not paid with regularity, had, since the peace of 1636, cultivated a good understanding with Shah Jehan, whom he courted through the influence of his eldest and favorite son, Dara Shekoh. This proceeding, in consequence of a secret jealousy between the brothers, drew upon Beejapoor, independent

of its being an object of his ambition, the personal enmity of Aurungzebe.

Mohummud Adil Shah was succeeded by his son, Sultan Ali Adil Shah the II.; who, immediately after his father’s death, mounted the throne of Beejapoor, in the nineteenth year of his age. The resources of his kingdom were still considerable; he had a large treasury, a fertile country, and his army, had it been properly concentrated, was powerful. The troops, however, were greatly divided, and large bodies of them were then employed in reducing the refractory Zumeendars in the Carnatic157.

As the throne was filled without complimentary reference, or the observance of any homage to which the emperor pretended a right of claim, agreeably, as he maintained, to an admission on the part of Mohummud Adil Shah, it was given out by the Moghuls, that Ali Adil Shah was not the son of the late king, and that the emperor must nominate a successor. The same circumstance is noticed in the works of contemporary European travellers158; but probably obtained from Moghul reports of that period, as nothing of the kind is alluded to in any of the Beejapoor writings, or in Mahratta manuscripts. This war, on the part of the Moghuls, appears to have been more completely destitute of apology than is commonly found, even

in the unprincipled transactions of Asiatic governments.

Meer Joomleh, by the emperor’s express appointment, and for a cause hereafter explained, was at the head of the army destined for the reduction of Beejapoor, in which Aurungzebe was only second in command. But Aurungzebe and Meer Joomleh had a secret understanding; the authority of the latter was nominal, that of the former supreme.

On the unexpected approach of the Moghuls, hasty preparations were made by the court of Beejapoor; but no army could be assembled sufficient to cope with them in the field. Strong garrisons were, therefore, thrown into the frontier places expected to be invested, whilst, in order to succour them with such horse as were in readiness, Khan Mohummud, the principal general, and several Mahomedan officers of note, took the field with all expedition. Shirzee Rao Ghatgay, Bajee Ghorepuray, Nimbalkur, and other Mahratta Jagheerdars promptly joined him with their troops159.

Aurungzebe was prepared to advance by the month of March 1657, and proceeded towards the frontier of the Beejapoor territory by the eastern route. The fort of Kallian was reduced almost immediately, and Beder, the garrison on which most dependence was placed, fell to the Moghuls in one day, owing, it is said, to an accidental explosion of the principal magazine.

Aurungzebe160 was greatly elated by this unexpected success; and his progress was expedited by every possible exertion. Kulburga was carried by assault, and no time was lost in prosecuting his march. The attack of the horse, who now began to annoy him, presented greater obstacles than any he had yet experienced; but he succeeded in corrupting Khan Mohummud, the prime minister and general of Beejapoor, who shamefully neglected every opportunity by which he might have impeded the march of the Moghuls161.

Some of the officers continued to exert themselves until they had suffered by an entire want of support, when the road was left open for Aurungzebe, by whom the capital was invested before the inhabitants had leisure to make their usual preparations of destroying the water, and bringing the forage, from the neighbourhood, within the gates.

The siege was pressed with great vigour, and the king sued for peace in the most humble mariner, offering to pay down one crore of rupees, and to make any sacrifice demanded; but Aurungzebe was aiming at nothing short of the complete reduction of the place, when an event occurred which suddenly obliged him to change his resolution. This circumstance was the supposed mortal illness

of the emperor, news of which, at this important moment, reached Aurungzebe, having been privately despatched by his sister Roshunara Begum.

Shah Jehan had four sons, Dara Shekoh, then with his father at Agra, Sultan Shuja, viceroy of Bengal, Aurungzebe employed as we have seen, and Sultan Moraud, governor of Guzerat. As all the sons aspired to the crown, each of them now assembled an army to assert his pretensions. Dara Shekoh, as soon as his father’s life was in danger, assumed the entire powers of the state; but he had previously been vested with great authority. To his influence was ascribed the order which obliged Aurungzebe to desist from the siege of Golcondah, and also the appointment of Meer Joomleh over his brother to the command of the army, at this time employed against Beejapoor. He was jealous of all his brothers, but he dreaded Aurungzebe. His apprehensions were well founded; the ambitious character of that prince, masked under the veil of moderation and religious zeal, was an over-match for the open and brave, but imprudent and rash disposition of Dara. The latter openly professed the liberal tenets which the court of Agra had derived from Akber, but which ill-accorded with the religious feelings of most of the Mahomedans in the imperial service. Aurungzebe perceived and took advantage of this circumstance, carrying his observances of the forms enjoined by the Koran to rigid austerity, and having, or pretending to have, nothing so much at heart as the interests of religion, and the propagation of the faith of Islam. One of the first

acts of Dara was to issue an order recalling Meer Joomleh and all the principal officers serving in the Deccan; a measure to which he may have been in some degree induced by partiality towards Beejapoor, as well as by hatred to his rival brother. Aurungzebe, by the advice of Meer Joomleh, immediately resolved on counteracting this order by marching to the Moghul capital. His first step was to accept the overtures of Ali Adil Shah, from whom he obtained a considerable supply of ready money, and concluded a treaty, by which he relinquished the advantages he had gained, and in a few days was on his march towards the Nerbuddah. As the family of Meer Joomleh were at Agra, in the power of Dara, the former suffered himself to be confined by Aurungzebe in the fort of Doulutabad, where Aurungzebe also lodged his own younger children and the ladies of his family. His second son, Sultan Mauzum, was left in charge of the government of Aurungabad. Aurungzebe’s first care was to deceive his brother Moraud Bukhsh, into a belief of his having no design upon the crown for himself; that such views were wholly inconsistent with the religious seclusion he had long meditated; that self-defence against the enemy, their brother Dara, obliged him to take up arms, and that he would join to assist in placing Moraud Bukhsh on the throne. Accordingly, their forces having united, they defeated the Imperial armies in two pitched battles. Dara became a fugitive; and although he afterwards assembled an army, he was again defeated, and at last betrayed into the hands of Aurungzebe, by whose orders he was put to

death. Shah Jehan, contrary to expectation, recovered from his illness, and during the advance of his sons, sent repeated orders, commanding them to return to their governments; but to these mandates they paid no attention, as they pretended to consider them forgeries by Dara.

As soon as Aurungzebe had his father in his power, he imprisoned Moraud Bukhsh, gained over his army, deposed the emperor, and mounted the throne in the year 1658162. Having sent for Meer Joomleh from the Deccan, they marched against his brother Shuja, discomfited his army, and forced him to fly to Arracan, where he was murdered, and Aurungzebe was thus left undisputed master of the empire.

141. It is not exactly known at what period the power of his predecessors commenced; but Hubush Khan, and Seedee Umber, were Abyssinian admirals of the Nizam Shahee fleet, during the time of Mullik Umber; and an Abyssinian officer named Seedee Bulbul was at that time in command of Rairee. Beejapoor MSS.

142. Jinjeera, the name by which the place is known in the Deccan, is the Mahratta corruption of the Arabic word Juzeerah, an island.

143. Seedee, when assumed by Africans themselves, has an honorable import, being a modification of the Arabic word syud, a lord; but, in the common acceptation, it is rather an appellation of reproach than of distinction.

144. Khafee Khan, Orme, and a loose traditionary Persian MS. procured from the collector and magistrate of the southern Concan.

145. The manner of surprising these forts is not satisfactorily explained; but, a traditionary account of one of Sivajee’s exploits, suggested a like attempt by a body of insurgents in the Concan–Ghaut–Mahta, who took up arms against the Peishwa’s government, in modern times, during the administration of Trimbukjee Dainglia. It was usual for the villagers, in the vicinity of the hill-forts, to contribute a quantity of leaves and grass for the purpose of thatching the houses in the fort, a practice said to have prevailed from before the time of Sivajee. The insurgents having corrupted one or two persons of the garrison, a party of them, each loaded with a bundle of grass, having his arms concealed below it, appeared at the gate in the dress of villagers, to deposit, as they pretended, the annual supply; and admittance being thus gained, they surprised the garrison, and possessed themselves of the place. The fort was Prucheetgurh, and the circumstance will be alluded to in its proper place; it is only mentioned here as a stratagem, the original merit of which is ascribed to Sivajee.

146. Mahratta MSS. Khafee Khan, Beejapoor MS. and tradition.

147. Mahratta MSS.

148. Original letters of the emperor Shah Jehan to Sivajee.

149. Colonel Wilks says Rendoollah Khan. His name in Mahratta MSS. is certainly always mentioned with Morar Punt’s, but Rendoollah Khan died in 1643, as appears on his tomb. He had a son or relation who had the same title, but he never attained sufficient rank or influence to have obtained Shahjee’s release.

150. Mahratta MSS.

151. Original letter from Shah Jehan. The original letters, from Shah Jehan and Aurungzebe, to Sivajee, are in the possession of the Raja of Satara. Copies of them are lodged with the Literary Society of Bombay.

152. Mahratta MSS.

153. Copy of the original instrument, and Mahratta MSS.

154. Sivajee called it Wujrgurh, a name which it has not retained.

155. Futih Khan had before changed the name to Futihnugur, which it did not retain. Beejapoor MS.

156. Beejapoor MSS.

157. Beejapoor MS.

158. Tavernier. Bernier. It is perhaps the same vulgar story, which Fryer relates regarding the son of Ali Adil Shah, and probably equally unfounded. See Fryer, p. 169.

159. Beejapoor MS.

160. In a letter to Sivajee he thus announces it: “The fort of Beder, which is accounted impregnable, and which is the key to the conquest of the Deccan and Carnatic, has been captured by me in one day, both fort and town, which was scarcely to have been expected without one year’s fighting.” Original letter from Aurungzebe to Sivajee.

161. Beejapoor MS.

162. There is a good deal of confusion in the dates of the reign of Aurungzebe, owing to its commencement having been frequently reckoned from 1659. Khafee Khan is, in consequence, sometimes thrown out one or two years. Aurungzebe appears to have begun by reckoning his reign from the date of his victory over Dora, to have subsequently ascended the throne in the following year, and then changed the date, which he again altered, by reverting to the former date, at some later and unknown period.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()