The want of a complete history of the rise, progress, and decline of our immediate predecessors in conquest, the Mahrattas, has been long felt by all persons conversant with the affairs of India; in so much, that it is very generally acknowledged, we cannot fully understand the means by which our own vast empire in that quarter was acquired, until this desideratum be supplied.

The difficulty of obtaining the requisite materials has hitherto deterred most of our countrymen from venturing on a subject where the indefatigable Orme has left his Fragments as a monument of his research, accompanied by an attestation of the labour which they cost him. The subsequent attempt of Mr. Scott Waring proved not only the difficulties of which Mr. Orme’s experience had warned us, but, that at a period comparatively recent, those who had the best opportunities of collecting information respecting the Mahrattas, were still very deficient in a knowledge of their history. Circumstances placed me in situations which at once removed many of the obstacles which those

gentlemen encountered, and threw materials within my reach which had been previously inaccessible: nevertheless, the labour and the expense, requisite for completing these volumes, can only be appreciated by those who assisted me in the design, or who have been engaged in similar pursuits in India.

On the subversion of the government of the Peishwas the most important of their state papers, and of their public and secret correspondence, were made over to me by Mr. Elphinstone, when he was acting under the orders of the Marquis of Hastings as sole commissioner for the settlement of the conquered territory in the Deccan. Captain Henry Dundas Robertson, collector and magistrate of Poona, with Mr. Elphinstone’s sanction, allowed confidential agents employed by me, to have access to the mass of papers which were found in the apartments of the Peishwa’s palaces. The Mahratta revenue state accounts were examined and extracted for me by the late Lieutenant John Macleod when first assistant to Mr. Chaplin who succeeded Mr. Elphinstone as commissioner for the conquered territory. The records of the Satara government were under my own immediate charge, and many original papers of historical importance, the existence of which was unknown to the Peishwas, were confided to me by the Raja. Mr. Elphinstone, when governor of Bombay, gave me free access to the records of that government; I had read the whole both public

and secret up to 1795, and had extracted what formed many large volumes of matter relative to my subject, when Mr. Warden the chief secretary, who had from the first afforded every facility to my progress, lent me a compilation from the records, made by himself; which shortened my subsequent labours and afforded materials amply sufficient, as far as regarded English history, for the years that remained. Mr. Romer, political agent at Surat, not only read, and at his I own expense extracted the whole of the records of the old Surat factory, but also sent me an important manuscript history in the Persian language which when referred to, as an authority, is acknowledged in its proper place. The viceroy of Goa most liberally furnished me with extracts from the records of the Portuguese government; and the Court of Directors allowed me to have partial access to those in the East India House for some particulars from the Bengal correspondence, and for authenticating a variety of facts, originally obtained from Mahratta authorities, but of which there is no trace in the secretary’s office at Bombay. The gentlemen of the India house were on every occasion most obliging: the very old records, under Dr. Wilkins, which I could not have read without great trouble, were made perfectly easy by the intelligence and kindness of Mr. Armstrong, one of the gentlemen in the office of Mr. Platt.

In regard to native authorities, besides the important papers already mentioned, records of temples

and private repositories were searched at my request; family legends, imperial and royal deeds, public and private correspondence, and state papers in possession of the descendants of men once high in authority; law suits and law decisions; and manuscripts of every description in Persian and Mahratta, which had any reference to my subject, were procured from all quarters, cost what they might. Upwards of one hundred of these manuscripts, some of them histories at least as voluminous as my whole work, were translated purposely for it. My intimate personal acquaintance with many of the Mahratta chiefs, and with several of the great Bramin families in the country, some of the members of which were actors in the events which I have attempted to record, afforded advantages which few Europeans could have enjoyed, especially as a great deal of the information was obtained during the last revolution in Maharashtra, when numerous old papers, which at any other period would not have been so readily produced, were brought forward for the purpose of substantiating just claims, or setting up unfounded pretensions. Latterly, however, I have to acknowledge many instances of disinterested liberality both from Bramins and Mahrattas, who of their own accord presented me with many valuable documents, and frequently communicated their opinions with much kindness and candour.

Next to Mr. Elphinstone, to whom I am indebted, not only for the situation which procured me most

of these advantages, but for an encouragement, without which I might never have ventured to prosecute this work, I am chiefly obliged to my friends, Captain Henry Adams, revenue-surveyor to the Raja of Satara, and Mr. William. Richard Morris of the Bombay civil service, then acting as my first assistant. These gentlemen translated many hundreds of deeds and letters, numerous treaties, several voluminous histories; and, for years together, were ever ready, at all hours after the transaction of public business, to give up their time in furtherance of my object. Captain Adams is the compiler, in many parts the surveyor of the Map of Maharashtra, which accompanies these volumes. I regret the necessity for its reduction, from a scale of six inches to a degree to that of its present comparatively incomplete size; still, however, the situations and distances of the places laid down, will, I believe, be found more correct than those of any map of that country hitherto published; and I am equally bound to acknowledge my obligations for the information I obtained, as if it had been offered to the public in its more perfect form. The original materials for Captain Adams’s map, were procured from his own surveys, from those of the late Captain Challen of Bombay, and of the late Captain Garling of Madras; which last were sent to me by Lieutenant Frederick Burr of the Nizam’s service, filled up in many places from his own routes. Captain James Cruickshank, revenue-surveyor in Guzerat, with

permission from the Bombay government, furnished me with such information as the records of the office of the late surveyor-general Reynolds afford, and with Sir John Malcolm’s map of Malwa, which, although then unpublished, that officer readily allowed me to use. Finally, the Court of Directors granted me permission to publish the information thus collected.

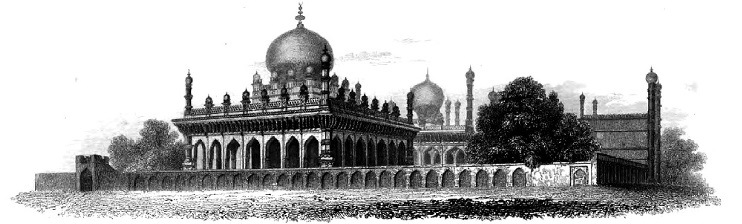

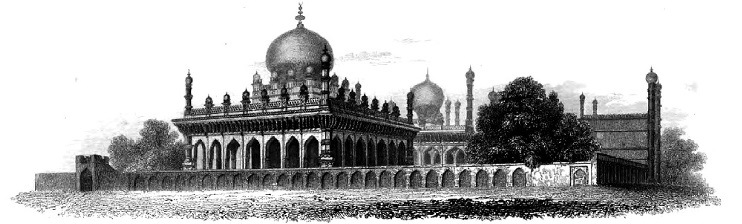

There were several drawings, and some likenesses of natives, by European artists, procured for the purpose of accompanying the history. Two of the drawings from the ruins of Beejapoor, by Lieutenant W. W. Dowell, of the Bombay establishment, the same gentleman to whom I am indebted for the frontispiece to volume 1st, were executed with admirable fidelity and precision, and would have been highly ornamental, if not illustrative; but as it was found that such minute engravings must have added greatly to the expense of the publication, which it was of importance to render moderate, I have been obliged to omit them.

A great part of this work was written in India; and as the chapters were prepared, I submitted them to all those gentlemen on the spot, who, from their situations or pursuits, seemed most likely to be able to corroborate facts, or to correct errors. It would be too long a list, nor can it be expected that I should enumerate all those who were so kind as to read portions of the manuscript, both in India and in England; but my thanks are due to Mr. William Erskine, of Edinburgh; to Lieutenant-Colonels Shuldham and, Vans Kennedy, of Bombay;

to Sir James Mackintosh; to Mr. Mill; to Mr. Jenkins; to Lieutenant-Colonel Briggs; and to Lieutenant John MacLeod, whose premature fate, in being cut off by a fever, at Bushire, where he had been appointed political resident, may be justly regarded as a loss to his country.

I have thus endeavoured to express my acknowledgments to all who favoured me with their advice or opinion, or who, in the slightest degree, assisted or contributed to these volumes: my particular obligations are commonly repeated in notes, where each subject is mentioned; but if I have omitted, in any one instance, to express what is justly due either to European or to Native, I can only say, the omission is not intentional, and proceeds from no desire to appropriate to myself one iota of merit to which another can fairly lay claim.

I am very sensible that I appear before the public under great disadvantages, as, indeed, everyone must do, who having quitted school at sixteen, has been constantly occupied nearly nine-tenths of the next twenty-one years of his life in the most active duties of the civil or military services of India; for, however well such a life may fit us for acquiring some kinds of information, it is in other respects ill-calculated for preparing us for the task of historians; yet unless some of the members of our service undertake such works, whence are the materials for the future historian to be derived, or how is England to become acquainted with India? Whilst I solicit indulgence, however,

to such defects as arise from this cause, it is also due to myself to apprize the reader, that independent of want of skill in the author, there are difficulties incidental to the present subject, besides harsh names and intricate details, with which even a proficient in the art of writing must have been embarrassed. The rise of the Mahrattas was chiefly attributable to the confusion of other states, and it was generally an object of their policy to render everything as intricate as possible, and to destroy records of rightful possession. As their armies overran the country, their history becomes blended with that of every other state in India, and may seem to partake of the disorder which they spread. As the only method, therefore, of preserving regularity, I have sometimes been obliged, when the confusion becomes extreme, rather to observe the chronological series of events than to follow out the connection of the subjects; a mode which will appear in some parts, especially of the first volume, to partake more of the form of annals than I could have wished; but persons who are better judges of composition than I pretend to be, found, upon examination, that the remedy might have obliged me either to generalize too much, or, what would have been still worse, to amplify unnecessarily. I have also afforded some explanations for the benefit of European readers, which those of India may deem superfluous; and on the other hand I have mentioned some names and circumstances, which I am certain, will hereafter prove useful to persons in

the Mahratta country, but which others may think might have been advantageously omitted.

There being differences of opinion as to whether the writer of history should always draw his own conclusions, or leave the reader to reflect for himself, I may expect censure or approbation according to the taste of parties. I have never spared my sentiments when it became my duty to offer them; but I have certainly rather endeavoured to supply facts than to obtrude my own commentaries; and though I am well aware that, to gain confidence with the one half of the world, one has only to assume it, I trust that I shall not have the less credit with the other for frankly acknowledging a distrust in myself.

It will also be apparent, that though I have spared no pains to verify my facts, I have seldom thought it necessary to contradict previous misstatements; for so many inaccuracies have been published on many points of Mahratta history, that it seemed far better simply to refer to my authorities, where strong and undeniable, than to enter on a field of endless controversy. At the same time I have endeavoured to give every opinion its due consideration; and, wherever it seemed of importance to state conflicting sentiments, I have not failed to lay them candidly before the reader, that he might rather exercise his own judgment than trust implicitly to mine. Still, however, in such a work many errors must exist: of these, I can only say, I shall feel obliged to any person who, after due consideration and

inquiry, will have the goodness, publicly or privately, to point them out.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()