In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, the three maritime peoples of the West – the English, Dutch, and French – had manifestly entered the lists of competition for commercial ascendency in Asiatic waters, Spain and Portugal having already fallen far into the rear. The English Company’s establishments in the East Indies consisted at this time of the presidency of Bantam, with Macassar and other places in the Indian Archipelago; Fort St. George and its dependent factories on the Coromandel Coast and in the Bay of Bengal; and Surat on the west coast of Bombay, with other subordinate posts on that side of India; as well as some places on the Persian Gulf.

It is of primary importance, in order to set in clear light the earlier subsequent stages of the rise of British dominion, and to explain why England finally distanced other competitors in this long and eventful race, that the vicissitudes of European politics in the latter part of this century should be briefly touched upon; because

the success of England in the East is largely due to the mistakes of France and the misfortunes of Holland in the West. From the beginning of the century the Eastern trade had been a make-weight and a perceptible element in the regulation of English policy abroad, for the London merchants had never been without means of influencing the court or the Parliament; but the adjustment of this important national interest to the varying exigencies of the general situation in Europe had about this time become peculiarly difficult.

During the interval between the Restoration of 1660 and the Revolution of 1688, when our commerce increased and throve mightily, we had to make head in Asia against the jealous antagonism of the Dutch; while in Europe the Dutch were our natural allies against the arbitrary aggressiveness of France. In the East it was of vital importance to our commerce that the power of Holland should be repressed, in the West we were vitally interested in upholding it; the balance of trade in Asia was inconsistent with the balance of politics in Europe. It was remarked by a contemporary diplomatist that England’s problem was to keep the peace with Holland without losing our East India trade; for if we supported the Dutch against France, they went on elbowing us out of Asia; while in joining France against Holland, we were breaking down one maritime power only to make room for another that might become much more formidable.

The organization of the French navy had now been seriously taken up; and in 1664 was founded the French

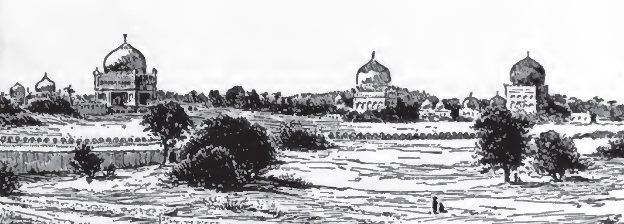

Bird’s-eye view of Trincomali

East India Company, which fitted out a squadron for the East Indies in the following year. In 1672, when England and France were allied against Holland, a French armament under De la Haye sailed for India, occupied the excellent harbour of Trincomali in Ceylon, and took possession of St. Thomé, close to Madras.

The English could not decently oppose the emissaries of a friendly nation, although this first appearance of the French on the Coromandel Coast – where in the next century our contest with them was fought out – could not but excite considerable uneasiness. Nor was the situation much improved in our favour when both places were subsequently captured from the French by the Dutch.

The foreign relations of England at this period were unsettled and curiously complicated. In 1665 Holland and England were at war; in 1666 France joined Holland against us; but in 1668 England, Holland, and

Sweden had formed the Triple Alliance against France; while in 1672 France and England combined to attack Holland; and in 1678 the English again made a defensive league with Holland against France, when the English Company were required by the government to send out a large body of men to defend Bombay, and also employed an armed fleet of some thirty-five vessels. The motives for these rapid changes of attitude were largely connected with Asiatic commerce.

The three wars against Holland into which England drifted between 1652 and 1672 were all prompted, more or less, by commercial and colonial animosities. For the quarrel in Cromwell’s time had arisen directly out of grievances against the Dutch in Asia; and we have seen that their determined attempts to thwart and repel the expansion of English commerce in the East Indies produced the rupture of 1665. France joined Holland in 1666, and some desperate naval engagements ensued, until the invasion of Spanish Flanders by Louis XIV so alarmed the Dutch that they consented to pacific proposals from the English and signed the Treaty of Breda in 1667 upon the basis of Uti possidetis as to territory, and the amicable adjustment of all commercial disputes.

England also made peace with France, but as Louis XIV nevertheless pushed on his invasion of Spanish Flanders, the Triple Alliance was formed to stop him by insisting on France and Spain coming to some arrangement. Then followed a fresh shuffle of the cards, for in 1670 the French and English kings agreed, by

their secret treaty of Dover, to make a joint attack upon the Dutch. It is a mistake to suppose, as is commonly thought, that Charles II was induced to join France in 1672 merely by French bribes and his sympathy with Roman Catholicism. His affiance with France was undoubtedly aimed against civil and religious liberty at home; but abroad one of its objects was to cut down the naval and commercial growth of Holland, with whom the English had many unsettled quarrels both in America and in Asia.

By a secret treaty projected between France, England, and Portugal in 1673, the three powers were to send a joint naval expedition against the Dutch possessions in Asia, which were to be seized and divided among the allies. It is thus clear that there were strong and recurrent motives for hostility between the two nations, closely connected with Asiatic affairs. Even Sir William Temple, the negotiator of the Triple Alliance, discusses in one of his essays the question whether England would derive greater advantage than France from the ruin of Holland. Whether in that case it would be possible to bring over to England the Dutch trade and shipping, seemed doubtful to him; yet he feared that, unless England joined France against Holland, the two Continental states might combine against England.

In 1671, accordingly, England did join France in a war which ended, so far as we were concerned, in 1674, when the Dutch agreed to salute the English flag in the narrow seas and to refer all commercial differences to

A Street Scene in Bombay

arbitration. Louis XIV, on the other hand, went on capturing town after town on the Flemish border; his great armies were overrunning Holland; and the Prince of Orange had declared that he would die in the last ditch. Finally, when the English had made a defensive treaty with Holland to save her from ruin, a general peace was ratified at Nimeguen in 1678, on terms very favourable to France, who retained many of the barrier towns in the Netherlands.

The upshot of these long continental wars was manifestly to strengthen England and to weaken Holland. In 1677, when the French invasion had thrown the Dutch into peril and distress, the commerce of England was prospering wonderfully. Moreover, the truce of 1678 was soon broken by fresh hostilities; and from that time up to the end of the century the French king was entirely engrossed in his ambitious and extravagant wars, while the Dutch were fighting desperately for their existence; so that the only two maritime powers from which England had anything to fear in the East were entangled in a great struggle on the European Continent. From these contests Holland emerged, at the Peace of Ryswick in 1697, with enfeebled strength, with her commerce severely damaged, and with her resources for distant expeditions materially reduced. But the Dutch had done much injury to the earliest French settlements planted under Colbert’s auspices in the East Indies; and France had been so much occupied on the land, particularly when the fortune of war began to turn against her, that she was now incapacitated

from pursuing Colbert’s wise and far-reaching schemes of commercial and colonial expansion. Her naval development was checked and her maritime enterprise took no fresh flight until after the Peace of Utrecht in 1713. In short, the French and Dutch had mutually disabled each other, to the great advantage, for operations beyond sea, of the English, who thenceforward begin to draw slowly but continuously to the foremost place in Asiatic conquest and commerce.

From this period of great Continental wars in Europe we may date the beginning of substantial prosperity for our East Indian trade; for it was then that the English made good their footing on the Indian coasts. We learn from Macaulay’s History that during the twenty years succeeding the Restoration, the value of the annual imports from Bengal alone rose from £8000 to £300,000, and that the gains of the Company from their monopoly of the import of East Indian produce were almost incredible. In 1685 the headquarters of their business on the Western side was transferred from Surat to Bombay; in 1687 the chief Bengal agency was removed from Hugh to Calcutta; and Madras had become their central post on the eastern shores of the Indian peninsula.

The Company were liberally encouraged by the government of the last two Stuarts, who granted ample charters, and even despatched armed reinforcements to their settlements. After the establishment of these three principal stations – which became afterwards, as Presidency towns, the cardinal points where the British

dominion was first fixed and whence it issued out into spacious radiation – the East India Company resolved, in 1687, to assume independent jurisdiction within their own settlements, to fortify them, to coin money, to collect customs, and to act, in short, as a self-governing body within their own limits. They now began to enlist a native militia for the purpose of using their chartered right of protecting themselves by reprisals against oppression or direct attack, and of fighting for their own hand in quarrels with the local governors or petty chiefs. The new system thus introduced contained the germ out of which these scattered trading settlements eventually expanded into wide territorial dominion; and the incipient weakness of the Moghul Empire furnished both the motives and the opportunity for the change.

So long as the imperial administration prevailed up to the limits of its farthest Indian provinces and was effectively felt on either seaboard, the English merchants were quite satisfied with licenses allowing them to compound for the export duties, with grants of land for building their factories, and with other privileges for which they paid readily while they got their money’s worth. But the outlying possessions of the empire were now no longer peacefully subordinate. The Maratha chief Sivaji was ranging about the Deccan, invading the Karnatic, and dominating the whole upper line of the west coast, not excluding the seaports and settlements held by Europeans. In 1664 he had pillaged Surat, where the English factory was bravely

Sivaji on the march

and successfully defended by Sir George Oxenden; and in 1671 he had levied heavy contributions on Surat and the Portuguese colony. Nor could the Moghul governors give any trustworthy protection, for Aurangzib’s attention was distracted by a revolt in Afghanistan, which he was totally unable to put down, despite a long and arduous campaign. When he returned to the Deccan, he found his enemies stronger than before in the field.

After Sivaji’s death in 1680, his son Sambaji continued the revolt; the imperial armies were gradually worn out by incessant warfare, by futile pursuits of an enemy that always avoided a decisive blow, and by the disorganization of the central government caused by the emperor’s long absence from his capital upon

distant campaigns. Aurangzib had destroyed the Mohammedan kingdoms of Golkonda and Bijapur in Southern India, which might at any rate have served as breakwaters against the spread of the Maratha insurrection; and the war was now becoming epidemic. The dislocation of the native administration led to the consolidation of the foreign settlements, since the Companies were compelled for their self-preservation to act upon this opportunity of taking up a more independent position in the country. The relaxation of the supreme legitimate authority loosened its hold on the more distant governorships, and with local irresponsibility came local oppression. The merchants became exposed to irregular extortion and capricious ransoming by subordinate officials who could give them no valid guarantees or regular safeguard; while their immunities and privileges, even when obtained at the capital from the emperor’s ministers, were often disregarded with impunity at the seaports.

Under these circumstances, the English Company convinced themselves, after much anxious discussion, that the success and comparative security of the Dutch, as formerly of the Portuguese, had been founded on their practice of seizing and openly fortifying posts strong enough to render the holders independent of the imperial pleasure, and to resist the arbitrary exactions of neighbouring officials or potentates. Their assumed jurisdiction was still to be confined entirely to the seacoast, and its object went no further than the security of their trade. But the English soon discovered

that the time had not yet come when a foreign flag could be safely set up on the Indian mainland. The Portuguese had established themselves at Goa before the Moghul Empire had extended to the west coast; the Dutch had fixed their independent settlements for the most part upon islands.

In the seventeenth century the power of the Moghul emperor, although undermined, was not yet so far reduced that he could be defied with impunity on his own seaboard. When, in 1687, the East India Company ventured to declare war against the Emperor Aurangzib, all the English settlements soon found themselves placed in great jeopardy by this rashness. It was lucky for the foreigners that the capture and execution of Sambaji, the Maratha leader, roused the Hindus of the southwest country to unite in strenuous revolt against the Mohammedan sovereign, who thereafter became too deeply entangled in the meshes of guerrilla warfare and sporadic insurrections to find leisure for dealing thoroughly with comparatively insignificant mercantile intruders. Moreover, since the Moghul government maintained no regular navy, it could not keep up a blockade of the harbours and river estuaries or bar the entry of foreign ships; while on the other hand the imperial customs revenue suffered heavily from their hostility.

The Emperor Aurangzib (better known in India by his title of Alamgir) was the last able representative of a dynasty that had conquered and ruled in India from the middle of the sixteenth century. The Moghul Empire was founded by the brilliant audacity and warlike

skill of Babar, a Chagatai Tartar, who, with an army of twelve thousand men, overthrew the dominion of the Pathan kings at Delhi and subdued all the northern provinces of India. It had been consolidated and raised to its full height of splendour and power by Akbar, a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth. Four successive emperors reigned one hundred and fifty-one years, from Akbar’s accession in 1556 to Aurangzib’s death in 1707; and as in Asia a long reign is always a strong reign, for a century and a half the Moghul was fairly India’s master.

The dynasty was foreign by descent and habits; the strength of the government was sustained by constant importation of fresh blood from abroad; the military and civil chiefs were mainly vigorous recruits from Central Asia who took service under the Indian sovereigns of their own race and religion. Akbar and his two successors were politic rulers who allied themselves with the princely families of the Hindus, respected up to a certain point the prejudices of the population, and kept both civil and religious despotism within reasonable bounds. The Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan were both sons of Hindu mothers; but Aurangzib, the son of Shah Jahan, and the fourth in descent from Akbar, was a Mohammedan by full parentage, and an ardent Islamite by temperament; and after his triumph in the great civil war that broke out among the sons of Shah Jahan, he launched out into a career of persecution and ambitious territorial aggrandizement. In the writings of Francois Bernier, a Frenchman who was

court physician to the Moghul emperor toward the beginning of Aurangzib’s long reign, may be found an excellent picture of the condition of the empire at that period. His book contains a lively sketch of contemporary history, and is full of striking observations upon the system of government, the composition of the army, and the more prominent features of Indian society and administration. Perhaps the most valuable part of it is the letter “Concerning Hindustan,” which Bernier wrote, after his return to France, to Colbert, the celebrated minister of Louis XIV, who had just set on foot the French East India Company that became the formidable rival of the English in the eighteenth century. His description of the military and official classes is instructive:–

“The great Moghul,” he says, “is a foreigner in Hindustan; consequently he finds himself in a hostile country, or nearly so, containing hundreds of Gentiles (Hindus) to one Moghul, or even to one Mohammedan. ... The court itself does not now consist, as originally, of real Moghuls, but is a medley of Uzbeks, Persians, Arabs, and Turks, or descendants from all these people.”

“It must not be imagined,” he elsewhere observes, “that the Omrah, or Lords, of the Moghul’s court are members of ancient families, as our nobility in France ... they mostly consist of adventurers from different nations, who entice one another to the court, and are generally persons of low descent, some having been originally slaves. The Moghul raises them to dignity

or degrades them to obscurity according to his own pleasure and caprice.”

Bernier goes on to show that the total insecurity of all private property, land revenue exactions, instability of government, the denial of justice, the tyranny and cupidity of the sovereign and his subordinates, “a tyranny often so excessive as to deprive the peasant and artisan of the necessaries of life, that drives the cultivator of the soil from his wretched home” – and that was ruining agriculture – accounted abundantly for the rapid decadence of all Asiatic states. “The country is ruined,” he says, “by the necessity of defraying the enormous charges required to maintain the splendour of a numerous court, and to pay a large army maintained for the purpose of keeping the people in subjection. No adequate idea can be conveyed of the sufferings of that people”; and he continues: “It is owing to this miserable system that most towns in Hindustan are made up of earth, mud, and other wretched materials; that there is no city or town which, if it be not already ruined or deserted, does not bear evident marks of approaching decay.” He thus touches upon the symptoms, already perceptible to a close observer, of the empire’s political and economical decline.

Soon after the date at which Bernier wrote, Aurangzib entered upon the interminable wars in South India which gradually involved him in the misfortunes and difficulties that darkened the last years of his reign. He succeeded in upsetting the minor Mohammedan kingdoms which had been strong enough to hold down

The lake of Utakamand in the Nilgiri hills, Southern India

Blank page

the Hindu population; but he had, in fact, weakened his empire by extending it; for the new southern provinces could not be effectively managed at a distance from the central authority, and the Hindus were not only provoked by his aggressive Mohammedan orthodoxy, but encouraged by his utter inability to control them.

The Moghul government, moreover, had never paid much attention to its sea frontier, being quite unaccustomed to expect foreign enemies or intruders from any other quarter than the north-west, through the Afghan passes. The only naval force on the Indian coast belonged to the Siddhis, an independent Abyssinian colony, whose chiefs occasionally placed their fleet at the disposal of Aurangzib for employment on the west side of the Indian peninsula.

To these causes and favouring circumstances, therefore, to the incipient decline of the central sovereignty, to the relaxation of imperial authority on the outskirts of the dominion, and especially to the commotion caused by the spread of the Hindu rebellion under energetic Maratha leaders, we may attribute the facility with which the English made good their foothold on the shores of India toward the close of the seventeenth century.

It is important, moreover, to remember that at the time when the mistakes and troubles of the Moghul empire were opening the gates of India to access from the sea, there set in an era of war in Europe which for many years disabled or diverted the resources of England’s

two maritime rivals, France and Holland. The reigns of the two autocratic monarchs who ruled France and India throughout the second half of the seventeenth century tally very nearly in point of time, for the dates of their respective accessions very nearly coincide; and they died early in the eighteenth century within a few years of each other. In the policy to which each of these celebrated rulers personally attached himself, and in its unfortunate consequences, there is also much more than a fanciful resemblance.

The accession of both Aurangzib and Louis XIV took place at a moment when the splendour and fame of their dynasties were in full lustre; they both inaugurated a career of conquest and unscrupulous attacks upon weaker neighbours that was at first triumphant; they both gradually undermined the prosperity of their kingdoms and the stability of their houses by wasteful and impolitic wars. Religious persecution of their own subjects, unwieldy centralization of all governmental authority by the levelling of local institutions, widespread corruption and a magnificent court under the influence of bigots, lackeys, and panders, were characteristics of the reign of the Bourbon as well as of the Moghul. And in each instance half a century’s autocratic misrule, complicated by unfortunate foreign wars, sectarian revolts, and grinding fiscal oppression, brought great misery on the people, and fatally enervated the monarchy.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century, the clouds began to gather, and from the beginning of the

eighteenth century the fortunes of both sovereigns were perceptibly on the wane. It so happened that the decline, or eclipse, of each power was eminently favourable to the rising commercial ascendency of the English nation.

In 1691, King William formed the grand alliance of the Germanic States and of the maritime powers, England, Holland, and Spain, against France; whereby the preponderance of the French was checked and their schemes of colonial and commercial expansion were thrown aside or trampled down in a great European war. For although the Peace of Ryswick suspended hostilities for a few years, it may be said that during practically the whole period from 1690 to 1713, the French monarchy was engaged in conflicts with all its European neighbours on a vast scale of ruinous expenditure.

The condition of the Moghul Empire was even worse. We have seen that during the seventeenth century, so long as the Moghul Empire retained its vigour, it was found impossible for any foreign adventurers to obtain more than a precarious footing, by sufferance, on the mainland of India. But when the eighteenth century opened, the disorder of the imperial government was manifestly culminating to a climax. The old age of Aurangzib; the persistence and contagious spread of the Hindu revolt against his oppression; the certainty that his death would be the signal for civil war among his sons, and that the succession must abide the chance of battle; financial distress and the visible loosening of

Peasants drawing water

his administration everywhere – these were the ordinary symptoms of debility, decay, and approximate dissolution in an Oriental dynasty.

In the north-west, the Persians and the rebellious Afghan tribes had now wrested from Aurangzib his border strongholds, and thus his grasp on that all-important frontier had become insecure, and the highroads from Central Asia were again open to invaders. In the southwest, the Moghul, after putting down the kingdoms of Bijapur and Golkonda, had been unable to reconstruct an administration strong enough to repress the turbulent elements that his impolitic demolitions had set free. The disbanded soldiery, the plundered peasants, and the disaffected Hindu landholders all rallied round the standard of the Maratha captains,

who bribed or daunted the imperial officials, harried the districts, cut off the revenue, and defeated the Moghul forces in detail. All these internal troubles were evident symptoms of the empire’s impending disruption, and the precursors of a great political change.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()