Clive’s victory in 1757 was followed by the military occupation of Bengal, which had an immense and far-reaching effect upon the position of the English in India. Their resources were so considerably increased that the defeat of the French in the Peninsula became thenceforward certain; for while Lally was cut off by sea and vainly attempting to support himself along a strip of seacoast, the English had their feet firmly planted in the Gangetic delta and the rich alluvial districts of the lower Ganges. The word Bengal must be understood, here and hereafter, to signify the great territory which includes the three provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, which were all under the rulership of the Nawab Siraj-ad-daulah. The subordination of the Bengal Nawabs to the English at once extended British predominance north-westward as far as the banks of the Ganges opposite Benares, and the capital of English political dominion was thenceforward established at Calcutta.

This transfer of the headquarters of the Company’s government to Calcutta marks a notable step forward,

A native boat of Bengal

since it was from Bengal, not from Madras or Bombay, that the English power first struck inland into the heart of the country and discovered the right road to supremacy in India: To advance into Bengal was to penetrate India by its soft and unprotected side. From Cape Comorin northward along the east coast there is not a single harbour for large ships; nor are the river estuaries accessible to them.

But at the head of the Bay of Bengal we come upon a low-lying deltaic region, pierced by navigable channels which discharge through several mouths the waters of great rivers issuing from the interior. Some of these are merely huge drains of the water-logged soil; others are fed by the Himalayan snows. On this section, and upon no other of the Indian seaboard, the rivers are wide waterways offering fair harbourage and the means of penetrating many miles inland; while around and beyond stretches the rich alluvial plain of Bengal, inhabited by a very industrious and unwarlike people, who produce much and can live on very little.

All authorities agree that in the eighteenth century

the richest province of all India, in agriculture and manufactures, was Bengal. Colonel James Mill, in his memoir already quoted above, points out that it has vast wealth and is indefensible toward the sea. “The immense commerce of Bengal,” says Verelst in 1767, “might be considered as the central point to which all the riches of India were attracted. Its manufactures find their way to the remotest parts of Hindustan.” It lay out of the regular track of invasion from Central Asia, and remote from the arena of civil wars which surged round the capital cities of the empire, Agra, Delhi, or Lahore. For ages it had been ruled by foreigners from the north; yet it was the province most exposed to maritime attack, and the most valuable in every respect to a seafaring and commercial race like the English. Its rivers lead like main arteries up to the heart of India. From Bengal north-westward, the land lies open, and, with few interruptions, is almost flat, expanding into the great central plain country that we now call the Northwest Provinces and Oudh, and further northward into the Panjab up to the foot of the Himalayan wall. Whoever holds that immense interior champaign country, which spreads from the Himalayas south-eastward to the Bay of Bengal, occupies the central position that dominates all the rest of India; and it may accordingly be observed that all the great capital cities founded by successive conquering dynasties have been within this region.

Looking now at a map of India, we perceive that upper or continental (as distinguished from peninsular)

India has been divided off from the rest of Asia by walls of singular strength and height. The whole of the Indian land frontier is fenced and fortified by mountain ranges; and where, in the southwest toward the sea, the mountains subside and have an easier slope, the Indian desert is interposed between the outer frontier and the fertile midland region. It is as if Nature, knowing the richness of the land and the comparative weakness of its people, had taken the greatest possible pains to protect it; for along the whole of that vast line of mountain wall which overhangs the north-west and the northern boundaries of India there are only a very few practicable passes.

These are the outlets through Afghanistan, by which Alexander the Great and all subsequent invaders have descended upon the low country; and anyone who, after traversing the interminable hills and stony valleys of Afghanistan, has seen, on mounting the last ridge, the vast plain of India spreading out before him in dusky haze like a sea, may imagine the feelings with which such a prospect was surveyed by those adventurous leaders when they first looked down on it from the edge of the Asiatic highlands. Along the whole northern line of frontier, the Himalayas are practically impassable; for the chain of towering mountains is backed by a lofty tableland, rising at its highest elevation to nearly seventeen thousand feet, which projects northward into Central Asia like the immense glacis of a fortress.

Such are the natural fortifications of India landward.

But an invader landing on the seaboard takes all these defences in reverse. He enters, as has been said, by open ill-guarded water-gates; he can penetrate into the centre of the fortress, can march up inside to the foot of the walls, can occupy the posts, and turn the fortifications against others. This is just what the English accomplished between 1757 and 1849, during the century occupied by their wars with the native powers in India. At the beginning of that period, the conquest of Bengal transferred the true centre of government from Southern India to that province; and thus we emerge rapidly into a far wider arena of war and politics.

For the English, after their victory at Plassey, the most urgent and important matter was the restoration of some regular administration. They had invested Mir Jafir with the Nawabship under a treaty which bound him to make heavy money payments to them in compensation for their losses by the seizure of Calcutta and other factories, and for their war expenditure; agreeing in return to supply troops at the Nawab’s cost whenever he should require them. The result was to drain the native ruler’s treasury and at the same time to reduce him, for the means of enforcing his authority and maintaining his throne, to a condition of dependence upon the irresponsible foreigners who commanded an army stationed within his province. Such a situation was by no means novel in India, where the leaders of well-disciplined troops are often as dangerous to their own government as to its enemies. At

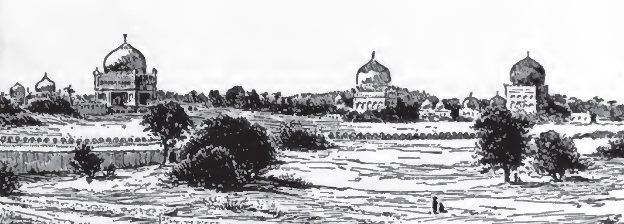

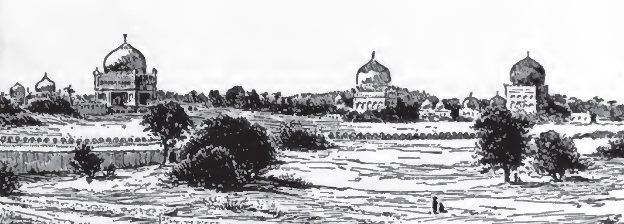

The great mosque at Kalbargah in Haidarabad

this very time, indeed, Bussy, with his French contingent at Haidarabad, was in much the same position as Clive with his English levies in Bengal. But when Lally had recalled Bussy from Haidarabad, the power of the French disappeared from the Deccan, and was soon after extinguished in their general discomfiture; while the English were now consolidating their supremacy over a kingdom that they had practically conquered.

The difficulty of this consolidation was greatly enhanced by the perplexity and indecision of the English as to their actual situation in the country. Although they were conquerors de facto, they neither could nor would assume the attitude of rulers de jure; they were merely the representatives of a commercial company with no warrant from their nation to annex territory, and were obliged to pretend deference toward a native ruler who was really subservient to themselves. Nothing

more surely leads to misrule than the degradation of a civil government to subserve the will of some arbitrary force or faction within the state; and in Bengal the evils of precarious and divided authority were greatly heightened by special aggravations.

In the first place, the Company and the Nawab were equally hard pressed for money. The Company was making large and emergent remittances to Madras for sustaining the war against the French, and it was obliged, at the same time, to maintain an army of more than six thousand men in Bengal. The Nawab, who did not choose to place himself entirely at the mercy of his foreign allies by disbanding his own forces, was beset by mutinous bands claiming arrears that he could not pay. Meanwhile, he wanted troops to put down disorder within his territories and to repulse attacks from without; for some of the principal landholders were in revolt against him; the Marathas were threatening Bengal on the west; and the heir apparent of the Delhi emperor had appeared with a force in the north-western districts, on the pretext of reclaiming a province of his father’s empire.

Secondly, the Company was not merely the Nawab’s too powerful auxiliaries, demanding a large share of his revenue as the price of their annual support; nor were they, like the Marathas or the Afghans, an army of occupation that might be bought out by disbursement of one huge indemnity. They represented an association which insisted upon regular remittances to Europe; their primary interests and objects were

still commercial; and as soon as they found themselves irresistible, they began to monopolize the whole trade in some of the most valuable products of the country. By investing themselves with political attributes without discarding their commercial character, they produced an almost unprecedented conjunction which engendered intolerable abuses and confusion in Bengal.

This is the only period of Anglo-Indian history which throws grave and unpardonable discredit on the English name. During the six years from 1760 to 1765, Clive’s absence from the country left the Company’s affairs in the hands of incapable and inexperienced chiefs, just at the moment when vigorous and statesmanlike management was urgently needed. That Clive himself clearly foresaw that the system would not answer and would not last, is shown by his letter written to Pitt in 1759, in which he suggested to the Prime Minister the acquisition of Bengal in full sovereignty by the English nation, promising him a net revenue of two millions sterling. In the meantime, he had done what he could to revive internal order and had forced the Delhi prince to evacuate the province.

The Dutch in Bengal, who naturally watched English proceedings with the utmost jealousy and alarm, were secretly corresponding with the Nawab and had brought over from Batavia a large body of troops. When their armed ships were prohibited by the English from ascending the river, they began hostilities, and were totally defeated by Colonel Forde in an action described by Clive’s report as “short, bloody, and

decisive.” But after Clive’s departure for England in 1760, the invasions from the outside were renewed; and within Bengal the whole administration was paralyzed by acrimonious disputes between the Company’s agents and the Nawab, who fought against his effacement and was secretly corresponding with the Dutch. Being intent, as was natural, on asserting his own independent authority, he manoeuvred to thwart and embarrass the Company, intrigued with their rivals, and did his best to disconcert their joint operations against the Marathas who were laying his country waste, since a defeat might at least help to shake off the English.

It followed that as neither party could govern tolerably, both soon became equally unpopular, and that during these years the country was in fact without an authoritative ruler. For while the English traders garrisoned the country with a large body of well-paid and well-disciplined troops, the whole duty of filling the military chest and carrying on an executive government fell upon -the Nawab, who was distracted between dread of assassination by his own officers and fear of dethronement by the Company.

As the English traders had come to Bengal avowedly with the sole purpose of making money, many of them set sail again for Europe as soon as they had made enough. In the meantime, finding themselves entirely without restraint or responsibility, uncontrolled either by public opinion or legal liabilities (for there was no law in the land), they naturally behaved as, in such circumstances and with such temptations, men would

Lord Clive

behave in any age or country. Some of them lost all sense of honour, justice, and integrity; they plundered as Moghuls or Marathas had done before them, though in a more systematic and businesslike fashion; the eager pursuit of wealth and its easy acquisition had blunted their consciences and produced general insubordination.

As Clive wrote later to the Company, describing the state of affairs that he found on his return in 1765, “In a country where money is plenty, where fear is the principle of government, and where your arms are ever victorious, it was no wonder that the lust of riches should readily embrace the proffered means of gratification,” or that corruption and extortion should prevail among men who were the uncontrolled

depositaries of irresistible force. This universal demoralization necessarily affected the revenues and exasperated the disputes between the Company and Mir Jafir by increasing the financial embarrassments of both parties; especially as the Nawab showed very little zeal in providing money for the troops upon whom rested the Company’s whole power of overruling him, and arrears were accumulating dangerously.

At last the president and council determined to put an end to these dissensions by removing the Nawab. An understanding was arranged with Mir Kasim, the Diwan, or chief finance minister, whereby he undertook to provide the necessary funds as a condition of his elevation to the rulership in the place of Mir Jafir, who was dispossessed by a bloodless revolution. But as the new Nawab had gained his elevation by outbidding his predecessor, this rack-renting revolution only made matters infinitely worse. Mir Kasim’s performances fell far short of his promises; the quarrels grew fiercer, and nothing was done to remedy the disorganization that was wrecking the administration and emptying the treasuries. The land revenue continued to decrease; commercial intercourse with upper India was checked by the insecurity of traffic; while the English Company was using their political ascendency not only to insist upon its privileged monopoly of the export trade to Europe, but also to enforce an. utterly unjust and extravagant claim for special exemption from all duties upon the internal commerce of Bengal. In the assertion of this pretension, the Company’s servants, native as

well as English, set at nought the Nawab’s authority, and their factories were in arms against his revenue officers.

All this violent friction soon culminated in an explosion, brought about by an awkward attempt on the part of Mr. Ellis, chief of the Patna factory, to seize Patna city, with the object of forestalling an attack by the Nawab on his factory. Although Ellis took the place, he could not hold it, and his whole party was captured in their retreat; but the Company’s troops marched against and defeated the Nawab, who, in his furious desperation, caused his English prisoners to be massacred and then fled across the frontier to the camp of the Vizir of Oudh. The Company, somewhat sobered by these tragic consequences of misrule, relinquished the more scandalous monopolies and restored Mir Jafir in 1763. When he died in 1765, the ruinous system of puppet Nawabs came practically to an end; for in that year Lord Clive, who had returned to India, assumed, under a grant from the Delhi emperor, direct administration of the revenue of the three provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, an office that was entitled the Diwani. The Diwan had been originally the controller-general on behalf of the imperial treasury in each province, with supreme authority over all public expenditure; so that the investiture of the Company with this office added the power of the purse to the power of the sword, and rendered them directly and regularly responsible for the most important departments of government.

We must now turn from internal affairs to the foreign relations of the East India Company and the general aspect of Indian politics. The Vizir of Oudh, when Mir Kasim took refuge with him, had in his camp the titular emperor of Delhi; and he thought the opportunity favourable for an expedition into the Bengal provinces with the professed object of restoring the imperial authority, but really with the intention of annexing such territory as he could seize. At Baxar, on the Ganges, he was met and signally defeated in September, 1764, by the Company’s troops under Major Hector Munro, in an engagement of which the eventual and secondary consequences were very important. The success of the English brought the emperor into their camp, intimidated the Vizir, carried the armed forces of the Company across the Ganges to Benares and Allahabad, and acquired for them a new, advanced, and commanding position in relation to the principalities north-west of Bengal, with whom they now found themselves for the first time in contact. By this war the English were drawn into connection with upper India, and were brought out upon a scene of fresh operations that grew rapidly wider.

At this point, therefore, it will be useful to sketch in loose outline the condition, in the middle of the last century, of that vast tract of open plain country, watered by the Jumna, the Ganges, and their affluents, which stretches from Bengal north-westward to the Himalayas, and which is now divided into the three British provinces of Oudh, the Northwest Provinces,

The Jami Masjid at Lucknow

and the Panjab. Throughout this vast region, the flood of anarchy that had been rising since Aurangzib’s death was now at its height; and as the struggle over the ruins of the fallen empire was sharpest at the capital and the centres of power, the districts round Delhi and Agra, Lucknow and Benares, were perhaps more persistently fought over than any other parts of India.

Two centuries of systematic despotism had long since levelled and pulverized the independent chiefships or tribal federations in these flat and fertile plains, traversed by highways open to every successive invader. So when the empire toppled over under the storms of the eighteenth century, there were no local breakwaters to check the inrush of confusion. The Marathas

swarmed up, like locusts, from the south, and the Afghans came pouring down from the north through the mountain passes. Within fifty years after the death of Aurangzib, who was at least feared throughout the length and breadth of India, the Moghul emperor had become the shadow of a great name, a mere instrument and figurehead in the hand of treacherous ministers or ambitious usurpers. All the imperial deputies and vicegerents were carving out independencies for them-selves, and striving to enlarge their borders at each other’s expense.

We have seen that the Nizam, originally Viceroy of the Southern Provinces, had long since made himself de facto sovereign of a great domain. In the north-west, the vizir of the empire was strengthening him-self east of the Ganges, and had already founded the kingdom of Oudh, which underwent many changes of frontier, but lasted a century. Rohilkhand had been appropriated by some daring adventurers known as Rohillas (or mountain men) from the Afghan hills; a sagacious and fortunate leader of the Hindu Jats was creating the State of Bhartpur across the Jumna River; Agra was held by one high officer of the ruined empire; Delhi, with the emperor’s person, had been seized by another; the governors sent from the capital to the Panjab had to fight for possession with. the deputies of the Afghan ruler from Kabul, and against the fanatic insurrection of the Sikhs.

These were, roughly speaking, the prominent and stronger competitors in the great scramble for power

and lands; but scarcely one of them (except the Sikhs) represented any solid organization, political principle, or title. Most of the rulerships depended on the personality of some chief or leader, who was raised more by the magnitude of his stakes than by the style of his play above the common crowd of plunderers and captains of soldiery. Anyone who had money or credit might buy at the imperial treasury a farman authorizing him to collect the revenue of some refractory district. If he overcame the resistance of the landholders, the district usually became his domain, and as his strength increased, he might expand into a territorial magnate; if the peasants rallied under some able headman and drove him off, their own leader often became a mighty man of his tribe and founded a petty chiefship or a ruling family. The traces of this chance medley and fluctuating struggle for the possession of the soil or of the rents were visible long afterwards in the complicated varieties of tenure, title, and proprietary usage that made the recording of landed rights and interests so perplexing a business for English officials in this part of India.

The English reader may now form some notion of the distracted condition of upper India when the Marathas invaded it in 1758 with a numerous army intended to carry out definite plans of conquest. The Moghul Empire was like a wreck among the breakers; the emperor Alamgir, who had long been a state prisoner, had been murdered; and the strife over the spoils had assumed the character of a wide-spreading free

fight, open to all comers. But as any such contest, if it lasts, will usually merge into a battle between distinct factions under recognized leaders, so the rapidly increasing power of the Marathas, who came swarming up from the southwest, and the repeated invasions from the north-west of Ahmad Shah Abdali with his Afghan bands, drew together to one or the other of these two camps all the self-made princes and marauding adventurers who were parcelling out the country among themselves. When Ahmad Shah brought an Afghan army to Delhi in 1757, he caused the office of prime minister to be conferred by the emperor on Najib-ad-daulah, one of the few able and politic nobles still attached to the Moghul government, who took a very leading part in subsequent events. At Lahore he appointed a viceroy to govern in his name the very important districts of the Panjab and to keep open his communications.

Having made these arrangements for maintaining his grasp on north India, the Afghan king had returned through the mountain passes to his own country. The Marathas took advantage of his absence with characteristic audacity. They were now overflowing all India with a flood-tide of conquest and pillage; and the supreme control of their confederacy was in the hands of Balaji Baji Rao, the ablest of those hereditary Peshwas, or prime ministers, who long kept their royal family in a state prison. While this powerful and politic ruler was extending Maratha dominion in the centre of India, his brother Raghunath Rao led northward

A Mohammedan tomb at Lahore

a large army, supported by the federal contingents of Holkar and Sind. Raghunath Rao seized Delhi, expelled Najib-ad-daulah; then marched swiftly with his light troops onward to Lahore, drove out the governor left there by Ahmad Shah, and substituted a Maratha administration in the Panjab.

This achievement marks, as Grant Duff observes in his “History of the Marathas,” the apogee of Maratha pre-eminence; “the Deccan horses had quenched their thirst in the waters of the Indus”; but it also marks the turning-point and ebb of their fortunes. By such a bold stroke for the possession of Northern India, they overreached themselves, for the effort drew them very far from their base; the Mohammedans were numerous and hardy in the north, and the Marathas

had now provoked a much more formidable antagonist in Ahmad Shah than any of those whom they had encountered heretofore. Their occupation of Delhi threatened all the Mohammedan princes of upper India, who saw that their only chance of preservation lay in a defensive affiance under some strong and warlike leader.

No exertions were spared by Najib-ad-daulah to organize such a league under Ahmad Shah; nor did the Afghan chief hesitate to answer the summons of the Indian Mussulmans, or to resent the provocation he had received. In the winter of 1759–1760, he came sweeping down through the north-west passes into the Panjab, followed by all the fighting men of Afghanistan; he retook Lahore at a blow; drove all the Maratha officers out of the northern country; attacked Holkar and Sind, who were plundering the districts farther south; defeated one after the other with heavy, loss; occupied Delhi; and continued his march south-eastward until he encamped on the Ganges. The Peshwa despatched a very large force from Poona, under his eldest son Visvas Deo, to repair these losses and recover lost ground; it was joined by all the other Maratha commanders, while on the other side the Mohammedan leaguers united with Ahmad Shah.

When the next campaigning season began, the two armies, after some negotiations and much manoeuvring, finally met in January, 1761, at Panipat, not far from Delhi. This was the greatest pitched battle that had been fought for several centuries between Hindus and

Mohammedans. Twenty-eight thousand Afghan horsemen rode with Ahmad Shah, whose army was brought up to a total of eighty thousand horse and foot by large bodies of infantry from his own dominions, and by the contingents of the Indian Mohammedans. The regular troops of the Marathas were reckoned at seventy-five thousand horse and fifteen thousand infantry; fifteen thousand Pindaris, or foraging freebooters, followed their standard; a countless swarm of armed banditti thronged their camp; and they had not less than two hundred guns. The artillery on both sides included strong rocket batteries.

The Marathas, who issued out of their entrenched camp at dawn, at first carried all before their furious onset; they broke through the lines of Persian musketeers, camel gunners, and light cavalry. The right wing of the Afghan army was thrown into confusion; its centre gave way under the crushing artillery fire. Ahmad Shah’s vizir, who commanded the centre, threw himself from his horse and strove to rally his men on foot, crying to them that their country was far distant and that flight was useless; but to his rage and despair he found himself being overwhelmed by the torrent.

In this peril, the Afghan king, very unlike the half-hearted Nawabs whom the English were routing farther south, proved his courage and high military capacity. With his right wing broken and his centre pierced, he checked or cut down the fugitives, brought up his reserves to the last man, and sent a strong reinforcement to his vizir, with orders to make a desperate

charge “sword in hand, in close order, at full gallop.” So the vizir remounted, and went storming down upon the Maratha centre under a shower of rockets. The Marathas fought bravely for a short time; but their leader was killed, their line was broken, and they were utterly routed with enormous slaughter; for the pursuit was by swarms of cavalry over a level plain, and the exasperated peasants massacred the Marathas everywhere.

The Peshwa, alarmed by the news of his army’s situation in the north, was moving up from the Deccan, and had reached the Narbada River. There his scouts brought him a runner who was carrying a letter from some bankers at Panipat to their correspondents in the south. He opened it and read: “Two pearls [his son and cousin] have been dissolved; twenty-seven gold mohurs lost; of the silver and copper the total cannot be reckoned,” an enigmatic message that told him of an immense political, military, and family catastrophe. He never recovered from the shock, which destroyed the baseless fabric of Maratha domination in Northern India. They might plunder towns, levy contributions, and even occupy some of the provinces for a time; but the fate of empires is decided by pitched battles, and in close lists the south-country freebooters would always go down before the hardier races of the north-west.

Such a decisive victory has usually been followed in Asia by the rise of a new dynasty and the establishment of an extensive dominion. Yet although the

Marathas were swept clean out of Northern India for the time, and although Ahmad Shah represented precisely the type of those Asiatic conquerors who had hitherto founded imperial houses at Delhi or Agra, it is a remarkable fact that the results of Panipat were quite disproportionate to the magnitude of the exploit. If Ahmad Shah had consolidated in the Panjab a powerful kingdom resting on Afghanistan beyond the Indus, and stretching southward down to Delhi and the Ganges, the history of India, and the fortunes of the English in that country, might have been very different. But his troops, laden with booty, insisted on retiring to their highlands; his western provinces on the Persian frontier were exposed to invasion and revolt; and so North India gradually slipped out of his grasp.

The Panjab relapsed into confusion for the next forty years, until it was temporarily consolidated under the kingdom of Ranjit Singh. Some inroads were made into India from Afghanistan, subsequently to Ahmad Shah’s retirement; but the Afghan ruler’s withdrawal practically closed the long line of conquering invaders from Central Asia, at a time very nearly simultaneous with the establishment in Bengal of the first conquer-ors that entered India by the sea.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()