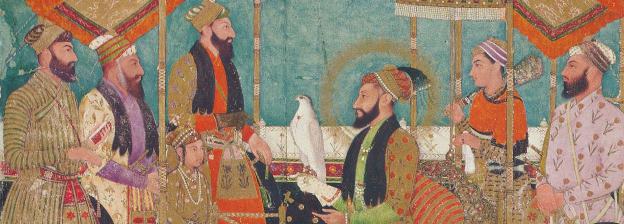

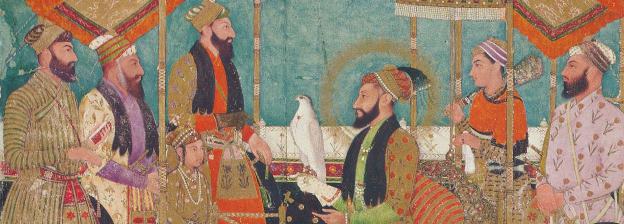

No ‘Turk’ – to use the term of the old travellers – was ever brought into more difficult and delicate relations with ‘infidels and heretics’ than the Great Mogul. The Grand Signior at Constantinople had his own troubles in this same seventeenth century with his Christian subjects in Hungary and Greece. But Aurangzib had to govern a people of whom at least three-fourths were what he termed infidels, and he had to govern them with the aid of officers who were no better than heretics to an orthodox Sunni. The vast majority of his subjects were Hindus; the best of his father’s governors and generals had been Persians of the sect of the Shi’a; and Aurangzib, in spite of his prejudices, found he could not do without those tried officials, if he was to make head against the leaders of the Hindus. The downtrodden peasantry could never give him serious trouble, indeed; but the Hindu Chiefs, the innumerable Rajas of the Rajput blood, dwelling in their mountain fastnesses about the Aravalli range and the Great Desert of India, were

a perpetual source of danger to the throne. There were more than a hundred of these native princes, some of whom could bring at least 20,000 horsemen into action; and far from being the ‘mild Hindus’ of the plains, they were born fighters, the bravest of the brave, urged to fury by a keenly sensitive feeling of honour and pride of birth, and always ready to conquer or die for their chiefs and their privileges. To see the Rajputs rush into battle, maddened with bang and stained with orange turmeric, and throw themselves recklessly upon the enemy in a forlorn hope, was a spectacle never to be forgotten. Had their Rajas combined their forces, it is probable that no Mughal army could have long stood against them. Happily for the empire they were weakened by internal jealousies, of which Aurangzib was not slow to take advantage. They could be played off, one against the other. Moreover, the wise conciliation of Akbar, following upon his triumphs in war, had done much to win the Rajput leaders over to the side of the invaders. There are few more instructive lessons in Indian history than the loyal response which the Hindu Chiefs made to the conciliating policy of Akbar. It was a Hindu, Todar Mal, who reduced Bengal to the imperial sceptre, and then organized the financial administration of the empire. Hindu generals and Brahman poets led Akbar’s armies, and governed some of his greatest provinces. Hindu clerks formed the chief official class in all departments where education was essential, and Rajput clans furnished the thews and

sinews of his armies. Every Mughal Emperor, even the orthodox Aurangzib, had carried on Akbar’s policy of marrying Raj put princesses, and seeking them as wives for his sons. It was a distinct loss of caste to the queens, and the Rajput pride kicked sorely at it; but there were counter-balancing advantages in such alliances, and they undoubtedly tended to bind the Native Chiefs to the Mughal throne.

What with Rajputs, Patans, and Persians, to say nothing of the parties in the Deccan, Aurangzib had a difficult population to deal with; and his first object, in self-defence, was to maintain a sufficient standing army to overawe each separate source of insurrection. He could indeed rely upon the friendly Rajas to take the field with their gallant followers against a Shi’ite kingdom in the Deccan, or in Afghanistan, and even against their fellow Rajputs, when the imperial cause happened to coincide with their private feuds. He could trust his Persian officers in a conflict with Mans or Hindus, though never against their Shi’ite coreligionists in the Deccan. But he needed a force devoted to himself alone, a body of retainers who looked to him for rank and wealth, and even the bare means of subsistence. This he found in the species of feudal system which had been inaugurated by Akbar. Just as the early Abbasid Khalifs had found safety and a sound imperial organization by selecting their provincial governors, not from the arrogant chiefs of the Arab clans, but from among their own freedmen, people

of no family, who owed everything to their lord, and were devoted to his interests: so the Mughal Emperors endeavoured to bind to their personal interest a body of adventurers of any sort of origin, generally of low descent, perhaps formerly slaves, and certainly uneducated, who derived their power and affluence solely from their sovereign, who ‘raised them to dignity or degraded them to obscurity according to his own pleasure and caprice.’ This body was called Mansabdars, or grant-holders, because each member received an income in money or land from the emperor. The jagir or estate of the mansabdar was the Mughal equivalent of the timar of the Ottoman timariots, and the feof of the Egyptian Mamluk. The value of the mansab, or grant, whether paid in cash or lands, was carefully graduated; so that there were a series of ranks among the grantees corresponding to the degrees of chin in the Russian bureaucracy. The ranks were distinguished in accordance with the number of horse a mansabdar was supposed to maintain: and we read of mansabdars of 500, or 1000, or 5000, and even 12,000 horse. The higher ranks, from 1000 horse upwards, received the title of Amir, of which the plural is Umara. The writings of European travellers are full of references to these ‘Omrahs,’ or nobles, as they call them, – though it must not be forgotten that the nobility was purely official, and had no necessary connexion with birth or hereditary estates. The term an ‘Amir of 5000,’ however, did not imply a following

of 5000 horsemen, though it doubtless meant this originally. It was merely a title of rank, and the number of cavalry that each Amir was bound to maintain was regulated by the King himself. An Amir of 5000 sometimes was ordered to keep only 500 horses; the rest was on paper only. As a matter of fact, he often kept much fewer than he was paid for; and what with false returns of his efficient force, and stopping part of the men’s pay, the grantee enjoyed a large income. Yet the heavy expenses of the Court, the extravagance and enormous establishments of the Amirs, and the ruinous presents they were forced to make to the Emperor at the annual festivals, exhausted their resources, and involved them deeply in debt. In Bernier’s time there were always twenty-five or thirty of these higher Amirs at the Court, drawing salaries estimated at the rate of from one to twelve thousand horse. The number in the provinces is not stated, but must have been very great, besides innumerable mansabdars or petty vassals of less than a thousand horse; of whom, besides, there were never less than two or three hundred at Court.’ These lower officers received from 150 to 700 rupees a month, and kept but two to six horses; and beneath them in rank were the Rauzinadars, who were paid daily, and often filled the posts of clerks and secretaries. The troopers who formed the following of the Amirs and mansabdars were entitled to the pay of 25 rupees a month for each horse, but did not always get it from their masters. Two horses to a man formed the usual

allowance, for a one-horse trooper was regarded as little better than a one-legged man.

The possessions and lands of an Amir, as well as of the inferior classes of mansabdars, were held only at the pleasure of the Emperor. When the grantee died, his title and all his property passed legally to the Crown, and his widows and children had to begin life again for themselves. The Emperor, however, was generally willing to make some provision for them out of the father’s savings and extortionate peculations, and a mansabdar often managed to secure a grant for his sons during his own lifetime. Careful Amirs, or their heirs, moreover, were expert in the art of concealing their riches, so as to defeat the law of imperial inheritance; and it is a question whether Aurangzib did not repudiate in practice, as he certainly did in writing, the obnoxious principle that the goods of the grantee should lapse to the Emperor to the exclusion of his natural heirs. The object, however, of keeping the control of the paid army, which these mansabdars maintained, in the royal hands, was effectually secured by the temporary character of the rank.

The cavalry arm supplied by the Amirs and lesser mansabdars and their retainers formed the chief part of the Mughal standing army, and, including the troops of the Rajput Rajas, who were also in receipt of an imperial subsidy, amounted in effective strength to more than 200,000 in Bernier’s time (1659-66), of whom perhaps 40,000 were about the Emperor’s person.

The regular infantry was of small account; the musketeers could only fire decently ‘when squatting on the ground, and resting their muskets on a kind of wooden fork which hangs to them,’ and were terribly afraid of burning their beards, or bursting their guns. There were about 15,000 of this arm about the Court, besides a larger number in the provinces; but the hordes of camp-followers, sutlers, grooms, traders, and servants, who always hung about the army, and were often absurdly reckoned as part of its effective strength, gave the impression of an infantry force of two or three hundred thousand men. All these people had directly or indirectly to be paid, and considering that there were few soldiers in the Mughal army who were not encumbered with wives, children, and slaves, it may be imagined that the army budget absorbed a very considerable part of the imperial revenue. There was also a small artillery arm, consisting partly of heavy guns, and partly of lighter pieces mounted on camels.

Whilst the Emperor kept the control of the army and nobles in his own hands by this system of grants of land or money in return for military service, the civil administration was governed on the same principle. Indeed, the civil and military characters were blended in the provincial administration. The mansab and jagir system pervaded the whole empire. The governors of provinces were mansabdars, and received grants of land in lieu of salary for the maintenance of their state and their

troops, and were required to pay about a fifth of the revenue to the Emperor41. All the land in the realm was thus parcelled out among a number of timariots, who were practically absolute in their own districts, and extorted the uttermost farthing from the wretched peasantry who tilled their lands. The only exceptions were the royal demesnes, and these were farmed out to contractors who had all the vices without the distinctions of the mansabdars. As it was always the policy of the Mughals to frequently shift the vassal-lords from one estate to another, in order to prevent their acquiring a permanent local influence and prestige, the same disastrous results ensued as in the precarious appointments of Turkey. Each governor or feudatory sought to exact all he could possibly get out of his province or jagir, in order to have capital in hand when he should be transplanted or deprived of his estate. Their authority in the outlying districts was to all intents and purposes supreme, for no appeal from their tyranny and oppression existed except to the Emperor himself, and they took good care that their proceedings should not be reported at Court. The local kazis or judges were the tools of the governor, and the imperial inspectors doubtless had their price for silence. Near Delhi or Agra or any of the larger towns such oppression and corruption could scarcely be concealed, and Aurangzib’s well-known love of justice would have instantly inflicted condign punishment: but in

the remoter parts of the Empire the cruelty and rapacity of the landholders went on almost unchecked. The peasantry and working classes, and even the better sort of merchants, used every precaution to hide such small prosperity as they might enjoy; they dressed and lived meanly, and suppressed all inclinations to raise themselves socially in. the scale of civilization. Very often they were driven to seek refuge in neighbouring lands, or took service under a native Raja who had a little more mercy to people of his own faith than could be expected from a Muhammadan adventurer.

Such was the administrative system of the Mughal Empire in the time of Aurangzib. In principle it was the same as in the days of Akbar; the difference lay only in the choice of an inferior, ill-educated class of Muslim officials, to the general exclusion of the more capable Hindus, and in the inadequate measures taken for local inspection and supervision. Aurangzib him-self strove to be a righteous ruler, but he was either afraid of arousing the discontent of his vassals by stringent supervision, or he was unable to secure the probity of a faithful body of inspectors. In either case the fact remains that while the central government was rigidly just and righteous, in the Muhammadan acceptation of law, the provincial administration was generally venal and oppressive. Whether we look at the military or the civil aspect of the system, it is clear that the Mughal domination in India was even more in the nature of an army of occupation than the

‘camp’ to which the Ottoman Empire has been compared. As Bernier says, ‘The Great Mogul is a foreigner in Hindustan: he finds himself in a hostile country, or nearly so; a country containing hundreds of Gentiles to one Mughal, or even to one Muhammadan.’ Hence his large armies; his network of feudatory governors and landholders dependent upon his countenance alone for their dignity and support; hence, too, an administrative policy which sacrificed the welfare of the people to the supremacy of an armed minority. Had the people been other than Hindus, accustomed to oppression, the system would have broken down. As it was, it preserved internal peace, and secured the authority of the throne during a long and critical reign. We read of few disturbances or insurrections in all these fifty years. Such wars as were waged were either campaigns of aggression outside the normal limits of the Empire, or were deliberately provoked by the Emperor’s intolerance.

The external wars are of little historical significance. Mir Jumla’s disastrous campaign in Assam was typical of many other attempts to subdue the north-east frontagers of India. The rains and the guerrilla tactics of the enemy drove the Mughal army to despair, and its gallant leader died on his return in the spring of 1663. ‘You mourn,’ said Aurangzib to Mir Jumla’s son, ‘you mourn a loving father, and I the most powerful and the most dangerous of my friends.’ The war in Arakan had more lasting effects. That kingdom had long been a standing menace to Bengal, and

a cause of loss and dread to the traders at the mouths of the Ganges. Every kind of criminal from Goa or Ceylon, Cochin or Malacca, mostly Portuguese or half-castes, flocked to Chittagong, where the King of Arakan, delighted to welcome any sort of allies against his formidable neighbour the Mughal, permitted them to settle. They soon developed a busy trade in piracy; ‘scoured the neighbouring seas in light galleys, called galleasses, entered the numerous arms and branches of the Ganges, ravaged the islands of Lower Bengal, and, often penetrating forty or fifty leagues up the country, surprised und carried away the entire population of villages. The marauders made slaves of their unhappy captives, and burnt whatever could not be removed42.’ The Portuguese settled at the Hugli had abetted these rascals by purchasing whole cargoes of cheap slaves, and had been punished for these and other misdeeds in an exemplary manner by Shah-Jahan, who took their town and carried the whole Portuguese population captive to Agra (1630). But though the Portuguese power no longer availed them, the pirates went on with their rapine, and carried on operations with even greater vigour from the island of Sandip, off Chittagong, where ‘ the notorious Fra Joan, an Augustinian monk, reigned as a petty sovereign during many years, having contrived, God knows how, to rid himself of the governor of the island.’ It was these freebooters who had sailed up to Dhakka, and enabled

Prince Shuja to escape with them to Arakan, robbing him secretly on the way.

When Shayista Khan came as Governor to Bengal, in succession to Mir Jumla, he judged it high time to put a stop to these exploits, besides punishing the King of Arakan for his treachery to Shuja, who, though a rival, was Aurangzib’s brother, and as such not to be treated with disrespect. Strange to relate, the pirates submitted at once to the summons of the Bengal governor (1666), backed as it was by the support of the Dutch, who were pleased to help in anything that might still further diminish the failing power of Portugal. The bulk of the freebooters were settled under rigorous supervision at a place a few miles below Dhakka, hence called Firingi-bazar, ‘the mart of the Franks,’ where some of their descendants still live. Shayista then sent an expedition against Arakan and annexed it, changing the name of Chittagong into Islamabad, ‘the city of Islam.’ He little knew that in suppressing piracy in the Gulf of Bengal he was materially assisting the rise of that future power, whose coming triumphs could scarcely have been foretold from the humble beginnings of the little factory established by the English at the Hugli in 1640. Just twenty years after the suppression of the Portuguese, Job Charnock defeated the local forces of the faujdar, and in 1690 received from Aurangzib, whose revenue was palpably suffering from the loss of trade and customs involved in such hostilities, a grant of land at Sutanati, which he immediately cleared of jungle and

fortified. Such was the modest foundation of Calcutta. The growth of the East India Company’s power, however, belongs to the period of the decline of the Mughal Empire: whilst Aurangzib lived, the disputes with the English traders were insignificant.

41. See below, p. 124.

42. Bernier, pp. 174–182.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()