With the conquest of Golkonda and Bijapur, Aurangzib considered himself master of the Deccan. Yet the direct result of this destruction of the only powers that made for order and some sort of settled government in the peninsula was to strengthen the hands of the Marathas. The check exercised upon these free-lances by the two Kingdoms may have been weak and hesitating, but it had its effect in somewhat restraining their audacity. Now this check was abolished; the social organization which hung upon the two governments was broken up; and anarchy reigned in its stead. The majority of the vanquished armies naturally joined the Marathas and adopted the calling of the road. The local officials set themselves up as petty sovereigns, and gave their support to the Marathas as the party most likely to promote a golden age of plunder. Thus the bulk of the population of the two dissolved States went to swell the power of Sambhaji and his highlanders, and the disastrous results of this revolution in Deccan politics were felt for more than a century. The anarchy

which desolated the Deccan was the direct forerunner of the havoc wrought by the Marathas in Delhi in the time of Shah-Alam and Wellesley.

The evil effects of the conquest were not immediately apparent. Aurangzib’s armies seemed to carry all before them, and the work of taking possession of the whole territory of the vanished kingdoms, even as far south as Shahji’s old government in Mysore, was swiftly accomplished. Sivaji’s brother was hemmed in at Tanjore, and the Marathas were everywhere driven away to their mountain forts. To crown these successes, Sambhaji was captured by some enterprising Mughals at a moment of careless self-indulgence. Brought before Aurangzib, the loathly savage displayed his talents for vituperation and blasphemy to such a degree that he was put to death with circumstances of exceptional barbarity (1689). His brother, Raja Ram, fled to Jinji in the Carnatic, as remote as possible from the Mughal head-quarters. For the moment, the Maratha power seemed to have come to an end. The brigands were awed awhile by the commanding personality and irresistible force of the Great Mogul. Had terms with such an enemy been possible or in any degree binding, Aurangzib might well have accepted some form of tributary homage, and retired to Delhi with all the honours of the war.

But the Emperor was not the man to look back when once his hand was set to the plough. He had accomplished a military occupation not merely of the Deccan, but of the whole peninsula, save the extreme

point south of Trichinopoly, and the marginal possessions of the Portuguese and other foreign nations. Military occupation, however, was not enough; he would make the southern provinces an integral part of his settled Empire, as finally and organically a member of it as the Punjab or Bengal. With this aim he stayed on and on, till a hope and will unquenchable in life were stilled in death. The exasperating struggle lasted seventeen years after the execution of Sambhaji and the capture of his chief stronghold: and at the end success was as far off as ever. ‘But it was the will of God that the stock of this turbulent family should not be rooted out of the Deccan, and that King Aurangzib should spend the rest of his life in the work of repressing them.’

The explanation of this colossal failure is to be found partly in the contrast between the characters of the invaders and the defenders. Had the Mughals been the same hardy warriors that Babar led from the valleys of the Hindu Kush, or had the Rajputs been the loyal protagonists that had so often courted destruction in their devoted service of earlier emperors, the Marathas would have been allowed but a short shrift. But Aurangzib had alienated the Rajputs forever, and they could not be trusted to risk their lives for him in the questionable work of exterminating a people who were Hindus, however inferior in caste and dignity. As for the Mughals, three or four generations of court-life had ruined their ancient manliness. Babar would have scorned to command such officers

as surrounded Aurangzib in his gigantic camp at Bairampur. Instead of hardy swordsmen, they had become padded dandies. They wore wadding under their heavy armour, and instead of a plain soldierly bearing they luxuriated in comfortable saddles, and velvet housings, and bells and ornaments on their chargers. They were adorned for a procession, when they should have been in rough campaigning outfit. Their camp was as splendid and luxurious as if they were on guard at the palace at Delhi. The very rank and file grumbled if their tents were not furnished as comfortably as in quarters at Agra, and their requirements attracted an immense crowd of camp followers, twenty times as numerous as the effective strength. An eye-witness describes Aurangzib’s camp at Galgala in 1695 as enormous: the royal tents alone occupied a circuit of three miles, defended all round with palisades and ditches and 500 falconets

‘I was told,’ he says, ‘that the forces in this camp amounted to 60,000 horse and 100,000 on foot, for whose baggage there were 50,000 camels and 3000 elephants; but that the sutlers, merchants and artificers were much more numerous, the whole camp being a moving city containing five millions of souls, and abounding not only in provisions, but in all things that could be desired. There were 250 bazars or markets, every Amir or general having one to serve his men. In short the whole camp was thirty miles about71.’

So vast a host was like a plague of locusts in a country: it devoured everything; and though at times it was richly provisioned, at others the Marathas cut off communications with the base of supplies in the north, and a famine speedily ensued.

The effeminacy of the Mughal soldiers was encouraged by the dilatory tactics of their generals. The best of all Aurangzib’s officers, Zu-l-Fikar, held treasonable parley with the enemy and intentionally delayed a siege, in the expectation that the aged Emperor would die at any moment and leave him in command of the troops. Such generals and such soldiers were no match for the hardy Marathas, who were inspired to a man with a burning desire to extirpate the Musalmans and plunder everything they possessed. The Mughals had numbers and weight; in a pitched battle they were almost always successful, and their sieges, skilfully conducted, were invariably crowned with the capture of the fort. But these forts were innumerable; and each demanded months of labour before it would surrender; and in an Indian climate there are not many consecutive months in which siege operations can be carried on without severe hardships. We constantly hear of marches during the height of the rains, the Emperor leading the way in his uncomplaining stoical fashion, and many of the nobles trudging on foot through the mud. In a single campaign no less than 4000 miles

were covered, with immense loss in elephants, horses, and camels. Against such hardships the effeminate soldiers rebelled. They were continually crying for ‘the flesh-pots of Egypt,’ the comfortable tents and cookery of their cantonment at Bairampur.

The Marathas, on the other hand, cared nothing for luxuries: hard work and hard fare were their accustomed diet, and a cake of millet sufficed them for a meal, with perhaps an onion for ‘point.’ They defended a fort to the last, and then defended another fort. They were pursued from place to place, but were never daunted, and they filled up the intervals of sieges by harassing the Mughal armies, stopping convoys of supplies, and laying the country waste in the path of the enemy. There was no bringing them to a decisive engagement. It was one long series of petty victories followed by larger losses.

To narrate the events of the guerrilla warfare, which filled the whole twenty years which elapsed between the conquest of Golkonda and the death of Aurangzib, would be to write a catalogue of mountain sieges and an inventory of raids. Nothing was gained that was worth the labour; the Marathas became increasingly objects of dread to the demoralized Mughal army; and the country, exasperated by the sufferings of a prolonged occupation by an alien and licentious soldiery, became more and more devoted to the cause of the I intrepid bandits, which they identified as their own. An extract from the Muhammadan historian, Khali Khan, who is loth to record disaster to his sovereign’s

arms, will give a sufficient idea of the state of the war in 1702. At this time Tara Bai, the widow of Ram Raja, was queen-regent of the Marathas, as Sambhaji’s son was a captive in the hands of Aurangzib. Tara Bai deserves a place among the great women of history:–

‘She took vigorous measures for ravaging the imperial territory, and sent armies to plunder the six provinces of the Deccan as far as Sironj, Mandisor, and Malwa. She won the hearts of her officers, and for all the struggles and schemes, the campaigns and sieges of Aurangzib, up to the end of his reign, the power of the Marathas increased day by day. By hard fighting, by the expenditure of the vast treasures accumulated by Shah-Jahan, and by the sacrifice of many thousands of men, he had penetrated into their wretched country, had subdued their lofty forts, and had driven them from house and home; still their daring increased, and they penetrated into the old territories of the imperial throne, plundering and destroying wherever they went. ... Whenever the commander of the army hears of a large caravan, he takes six or seven thousand men and goes to plunder it. If the collector cannot levy the chauth, the general destroys the towns. The head men of the villages, abetted by the Marathas, make their own terms with the imperial revenue-officers. They attack and destroy the country as far as the borders of Ahmadabad and the districts of Malwa, and spread their devastations through the provinces of the Deccan to the environs of Ujjain. They fall upon and plunder caravans within ten or twelve kos of the imperial camp, and have even had the hardihood to attack the royal treasure72.’

They carried off the imperial elephants within hail of the cantonments, and even shut the Emperor up in his own trenches, so that ‘not a single person durst venture out of the camp73.’

The marvellous thing about this wearisome campaign of twenty years is the way in which the brave old Emperor endured its many hardships and disappointments.

‘He was nearly sixty-five when he crossed the Narbada to begin on this long war, and had attained his eighty-first year before he quitted his cantonment at Bairampur [to make his last grand sweep over the Maratha country]. The fatigues of marches and sieges were little suited to such an age; and in spite of the display of luxury in his camp equipage, he suffered hardships that would have tried the constitution of a younger man. While he was yet at Bairampur, a sudden flood of the Bhima overwhelmed his cantonment in the darkness of the night, and during the violence of one of those falls of rain which are only seen in tropical climates: a great portion of the cantonment was swept away, and the rest laid under water; the alarm and confusion increased the evil: 12,000 persons are said to have perished, and horses, camels, and cattle without number. The Emperor himself was in danger, the inundation rising over the elevated spot which he occupied, when it was arrested (as his courtiers averred) by the efficacy of his prayers. A. similar disaster was produced by the descent of a torrent during the siege of Parli; and, indeed, the storms of that inclement region must have exposed him to many sufferings during the numerous rainy seasons he spent within it. The impassable streams, the flooded valleys, the miry bottoms, and narrow ways, caused

still greater difficulties when he was in motion; compelled him to halt where no provisions were to be had; and were so destructive to his cattle as sometimes entirely to cripple his army. The violent heats, in tents, and during marches, were distressing at other seasons, and often rendered over-powering by the failure of water: general famines and pestilences came more than once, in addition to the scarcity and sickness to which his own camp was often liable; and all was aggravated by the accounts of the havoc and destruction committed by the enemy in the countries beyond the reach of these visitations74.’

In the midst of these manifold discouragements Aurangzib displayed all his ancient energy. It was he who planned every campaign, issued all the general orders, selected the points for attack and the lines of entrenchment, and controlled every movement of his various divisions in the Deccan. He conducted many of the sieges in person, and when a mine exploded on the besiegers at Sattara, in 1699, and general despondency fell on the army, the octogenarian mounted his horse and rode to the scene of disaster ‘as if in search of death.’ He piled the bodies of the dead into a human ravelin, and was with difficulty prevented from leading the assault himself. He was still the man who chained his elephant at the battle of Samugarh. Nor was his energy confined to the overwhelming anxieties of the war. His orders extended to affairs in Afghanistan, and disturbances at Agra; he even thought of retaking Kandahar. Not an

officer, not a government clerk, was appointed without his knowledge, and the conduct of the whole official staff was vigilantly scrutinized with the aid of an army of spies.

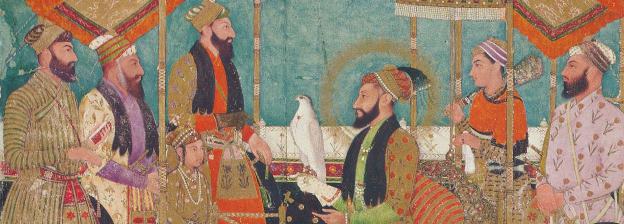

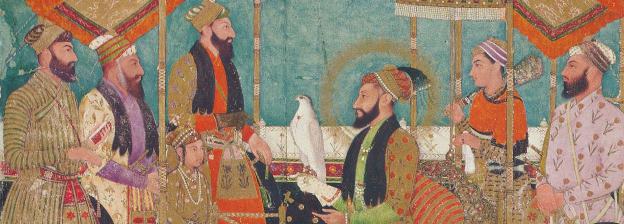

We are fortunate in possessing a portrait75 of Aurangzib, as he appeared in the midst of his Deccan campaigns. On Monday the 21st of March, 1695, Dr. Gemelli Careri was admitted to an audience of the Emperor in his quarters, called ‘Gulalbar,’ at the camp of Galgala. He saw an old man with a white beard, trimmed round, contrasting vividly with his olive skin; ‘he was of low stature, with a large nose; slender and stooping with age.’ Sitting upon rich carpets, and leaning against gold-embroidered cushions, he received the Neapolitan courteously, asked his business in the camp, and, being told of Careri’s travels in Turkey, made inquiries about the war then raging between the Sultan and the princes of Hungary. The doctor saw him again at the public audience in the great tent within a court enclosed by screens of painted calico. The Mughal appeared leaning on a crutched staff, preceded by several nobles. He was simply attired in a white robe, tied under the right arm, with a silk sash, from which his dagger hung. On his head was a white turban bound with a gold web, ‘on which an emeraud of a vast bigness appear’d amidst four little ones. His shoes were after the Moorish fashion, and his legs naked without

hose.’ He took his seat upon a square gilt throne raised two steps above the dais, inclosed with silver banisters; three brocaded pillows formed the sides and back, and in front was a little silver footstool. Over his head a servant held a green umbrella to keep off the sun, whilst two others whisked the flies away with long white horsetails. ‘When he was seated they gave him his scimitar and buckler, which he laid down on his left side within the throne. Then he made a sign with his hand for those that had business to draw near; who being come up, two secretaries, standing, took their petitions, which they delivered to the King, telling him the contents. I admir’d to see him indorse them with his own hand, without spectacles, and by his cheerful smiling countenance seem to be pleased with the employment.’

One likes to think of Aurangzib as the Neapolitan doctor saw him, simply dignified, cheerfully busy, leading his austere life of devotion and asceticism in the midst of his great camp in the Deccan. It is a wonderful picture of the vigorous old age of one who allowed no faculty of his active mind to rust, no spring of his spare frame to relax. But behind that serene mask lay a. gloomy, lonely soul. It was the tragical fate of the Mughal Emperor to live and die alone. Solitary state was the heritage of his rank, and his natural bent of mind widened the breach that severed him from those around him. The fate of Shah-Jahan preyed upon his mind. He was wont to remind his sons that he was not one to be treated

as he had used his own father. His eldest son had paid the penalty of his brief and flighty treason by a life-long captivity; and Aurangzib had early impressed the lesson upon the second brother. ‘The art of reigning,’ he told Mu’azzam, ‘is so delicate, that a king must be jealous of his own shadow. Be wise, or a fate like your brother’s will befall you also.’ Mu’azzam had been docility personified, but his father’s suspicion had been aroused more than once, and his next brother A’zam had shown a strictly Mughal spirit in fanning the sombre glow, till the exemplary heir was thrown into prison, where he endured a rigorous captivity for seven years (1687-94). On his release, A’zam became in turn the object of jealousy, perhaps with better reason, and a curious story is told of the way in which the Emperor convinced his son of the futility of conspiracy:–

‘Having imbibed a suspicion that this Prince was meditating independence, he sent for him to Court; and as the Prince made excuses and showed alarm, he offered to meet him slightly attended on a hunting-party. A’zam on this set out, and Aurangzib secretly surrounded the place of meeting with chosen troops: as the Prince got more and more within his toils, the old Emperor found a succession of pretences for requiring him gradually to diminish the number of his attendants, until, when they reached the place where his father was, they were reduced to three persons. As’ nobody offered to undertake the duty, he was obliged to leave two of his companions to hold his horses; and be and the remaining attendant were disarmed before they were admitted to the royal presence. On this he gave himself up

for lost, and had no doubt that he was doomed to a long or perpetual imprisonment. But when he was introduced to his father, he was received with an affectionate embrace: Aurangzib, who was prepared for shooting, gave his loaded gun for him to hold, and then led him into a retired tent, where he showed him a curious family sword, and put it naked into his hand that he might examine it; after which he threw open his vest, on pretence of heat, but really to show that he had no hidden armour. After this display of confidence, he loaded A’zam with presents, and at last said he had better think of retiring, or his people would be alarmed at his detention. This advice was not premature: A’zam, on his return, found his whole camp on the point of breaking up, and his women weeping and lamenting his supposed fate. Whether he felt grateful for his easy dismission does not appear; but it is recorded that he never after received a letter from his father without turning pale76.’

One son after another was tried and found wanting by his jealous father. Mu’azzam after his seven years’ captivity was sent away to govern the distant province of Kabul. A’zam, who had shown considerable zeal in the Deccan wars, was dismissed to the government of Gujarat. Aurangzib, though painfully conciliatory to these two sons, and lavish of presents and kind words, seems never to have won their love. At one time he showed a preference for Prince Akbar, whose insurrection among the Rajputs soured his fatherly affection and increased his dread of his sons’ ambition. Towards the close of his life he was drawn closer to his youngest son, Kam-Bakhsh,

whose mother, Udaipuri Bai, was the only woman for whom the Emperor entertained anything approaching to passionate love77. The young Prince was suspected of trafficking the imperial honour with the Marathas, and placed under temporary arrest, but his father forgave or acquitted him, and his last letters breathe a tone of tender affection which contradicts the tenour of his domestic life.

His officers were treated with the same consideration, and the same distrust, as his elder sons. To judge from his correspondence, there never were generals more highly thought of by their sovereign. ‘He condoles with their loss of relations, inquires about their illnesses, confers honours in a flattering manner, makes his presents more acceptable by the gracious way in which they are given, and scarcely ever passes a censure without softening it by some obliging expression:’ but he keeps all the real power and patronage in his own hands, and shifts his governors from place to place, and surrounds them with spies, lest they should acquire undue local influence. It would be a gross injustice to ascribe his universal graciousness to calculating diplomacy, though his general leniency and dislike to severe punishments,

save when his religion or his throne was at stake, were no doubt partly due to a politic desire to avoid making needless enemies. Aurangzib was naturally clement, just, and benevolent: but all his really kind actions were marred by the taint of suspicion, and lacked the quickening touch of trusting love. He never made a friend.

The end of the lonely unloved life was approaching. Failure stamped every effort of the final years. The Emperor’s long absence had given the rein to disorders in the north; the Rajputs were in open rebellion, the Jats had risen about Agra, and the Sikhs began to make their name notorious in Multan. The Deccan was a desert, where the track of the Marathas was traced by pillaged towns, ravaged fields, and smoking villages. The Mughal army was enfeebled and demoralized, ‘those infernal foot-soldiers’ were croaking like rooks in an invaded rookery, clamouring for their arrears of pay. The finances were in hopeless confusion, end Aurangzib refused to be pestered about them. The Marathas became so bold that they plundered on the skirts of the Grand Army, and openly scoffed at the Emperor, and no man dared leave the Mughal lines without a strong escort. There was even a talk of making terms with the insolent bandits.

At last the Emperor led the dejected remnant of his once powerful army, in confusion and alarm, pursued by skirmishing bodies of exultant Marathas, back to Ahmadnagar, whence, more than twenty years before, he had set out full of sanguine hope, and at

the head of a splendid and invincible host. His long privations had at length told upon his health, and when he entered the city he said that his journeys were over. Even when convinced that the end was near, his invincible suspicions still mastered his natural affections. He kept all his sons away, lest they should do even as he had done to his own father. Alone he had lived, and alone he made ready to die. He had all the Puritan’s sense of sin and unworthiness, and his morbid creed inspired a terrible dread of death. He poured out his troubled heart to his sons in letters which show the love which all his suspicion could not uproot.

‘Peace be with you and yours,’ he wrote to Prince A’zam, ‘I am grown very old and weak, and my limbs are feeble. Many were around me when I was born, but now I am going alone. I know not why I am or wherefore I came into the world. I bewail the moments which I have spent forgetful of God’s worship. I have not done well by the country or its people. My years have gone by profitless. God has been in my heart, yet my darkened eyes have not recognized his light. Life is transient, and the lost moment never comes back. There is no hope for me in the future. The fever is gone: but only skin and dried flesh are mine. ... The army is confounded and without heart or help, even as I am: apart from God, with no rest for the heart. They know not whether they have a King or not. Nothing brought I into this world, but I carry away with me the burthen of my sins. I know not what punishment be in store for me to suffer. Though my trust is in the mercy and goodness of God, I deplore my sins. When I have lost hope in myself, how can I hope in other! – Come what will, I have

launched my bark upon the waters. ... Farewell! Farewell! Farewell!’

To his favourite Kam-Bakhsh he wrote:–

‘Soul of my soul ... Now I am going alone. I grieve for your helplessness. But what is the use? Every torment I have inflicted, every sin I have committed, every wrong I have done, I carry the consequences with me. Strange that I came with nothing into the world, and now go away with this stupendous caravan of sin! ... Wherever I look I see only God. ... I have greatly sinned, and I know not what torment awaits me. ... Let not Muslims be slain and the reproach fall upon my useless head. I commit you and your sons to God’s care, and bid you farewell. I am sorely troubled. Your sick mother, Udaipuri, would fain die with me. ... Peace!’

On Friday, the 4th of March, 1707, in the fiftieth year of his reign, and the eighty-ninth of his life, after performing the morning prayers and repeating the creed, the Emperor Aurangzib gave up the ghost. In accordance with his command, ‘Carry this creature of dust to the nearest burial-place, and lay him in the earth with no useless coffin,’ he was buried simply near Daulatabad beside the tombs of Muslim saints.

‘Every plan that he formed came to little good; every enterprise failed:’ such is the comment of the Muhammadan historian on the career of the sovereign whom he justly extols for his ‘devotion, austerity, and justice,’ and his ‘incomparable courage, long-suffering, and judgment.’ Aurangzib’s life had been a vast failure, indeed, but he had failed grandly. He had pitted his conscience against the world, and the world

had triumphed over it. He had marked out a path of duty and had steadfastly pursued it, in spite of its utter impracticability. The man of the world smiles at his short-sighted policy, his ascetic ideal, his zeal for the truth as he saw it. Aurangzib would have found his way smooth and strewn with roses had he been able to become a man of the world. His glory is that he could not force his soul, that he dared not desert the colours of his faith. He lived and died in leading a forlorn hope, and if ever the cross of heroic devotion to a lost cause belonged to mortal man, it was his. The great Puritan of India was of such stuff as wins the martyr’s crown.

His glory is for himself alone. The triumph of character ennobled only himself. To his great empire his devoted zeal was an unmitigated curse. In his last letters he besought his sons not to strive against each other. ‘Yet I foresee,’ he wrote, ‘that there will be much bloodshed. May God, the Ruler of hearts, implant in yours the will to succour your subjects, and give you wisdom in the governance of the people.’ His foresight presaged something of the evil that was to come, the fratricidal struggle, the sufferings of the people. But the reality was worse than his worst fears. It was happy for him that a veil concealed from his dying eyes the shame and ignominy of the long line of impotent successors that desecrated his throne, the swelling tide of barbarous invaders from the south, the ravages of Persian and Afghan armies from the north, and the final triumph of the infidel

traders upon whose small beginnings in the east and west of his wide dominions he had hardly condescended to bestow a glance. When Lord Lake entered Delhi in 1803, he was shown a miserable blind old imbecile, sitting under a tattered canopy. It was Shah-’Alam, ‘King of the World,’ but captive of the Marathas, a wretched travesty of the Emperor of India. The British General gravely saluted the shadow of the Great Mogul. To such a pass had the empire of Akbar been brought by the fatal conscience of Aurangzib. The ludibrium rerum humanarum, was never more pathetically played. No curtain ever dropped on a more woeful tragedy.

Yet Akbar’s Dream has not wholly failed of its fulfilment. The heroic bigotry of Aurangzib might indeed for a while destroy those bright hopes of tolerant wisdom, but the ruin was not for ever. In the progress of the ages the vision glorious’ has found its accomplishment, and the desire of the great Emperor has been attained. Let Akbar speak in the latest words of our own lost Poet:–

‘Me too the black-winged Azrael overcame,

But Death hath ears and eyes; I watched my son,

And those that follow’d, loosen, stone from stone,

All my fair work; and from the ruin arose

The shriek and curse of trampled millions, even

As in the time before; but while I groan’d,

From out the sunset pour’d an alien race,

Who fitted stone to stone again, and Truth,

Peace, Love and Justice came and dwelt therein.’

71. Dr. J. F. Gemelli Careri, Voyage Round the World, Churchill Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. iv. p. 221 (1745). He adds that the total army amounted to 300,000 horse and 400,000 foot. He doubtless fell into the common error of including a large proportion of camp followers in the infantry.

72. See Elliot and Dowson, vol. vii. p. 375.

73. Bundela officer’s narrative, in Scott’s Deccan, pp. 109, 116.

74. Elphinstone (1866), pp. 665, 666.

75. Gemelli Careri, Voyage Round the World, Churchill Coll., vol. iv. pp. 222, 223.

76. Elphinstone (1866), pp. 667, 668.

77. Aurangzib’s wives played but a small part in his life. According to Manucci the chief wife was a Rajput princess, and became the mother of Muhammad and Mu’azzam, besides a daughter. A Persian lady was the mother of A’zam and Akbar and two daughters. The nationality of the third, by whom the Emperor had one daughter, is not recorded. Udaipuri, the mother of Kam-Bakhsh, was a Christian from Georgia, and had been purchased by Dara, on whose execution she passed to the harim of Aurangzib.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()