By Ken Moore

I last walked on the Bolin Creek Trail in Chapel Hill in August, when I was excited to discover Polymnia uvedalia, bearsfoot, all along the woodland edges. Bearsfoot was well past peak flower when I described it in Flora on Aug. 6.

I was surprised to see it beginning to flower this past weekend when I revisited the trail after such a long absence. This year’s flowering is weeks earlier than last year.

With this advance notice, you’ll have ample time to enjoy it before it completes this year’s flowering cycle.

That was the first of many surprises I encountered during this past Sunday’s walk on the greenway along the creek.

Early on, I was overtaken by a friend who regularly jogs along the pathway. He stopped to alert me to “take a closer look†up ahead where the creek forms a couple of fish-filled pools frequently visited by one or more great blue herons. He further advised me to keep an eye open for the muskrat he had recently seen.

I found the pool, sure enough filled with minnows and a couple of perch-like fish big enough to eat. The heron took off as I advanced. But while I was kneeling down photographing elderberry fruit overhanging the pool, a muskrat, mouth full of vegetation, swam by paying no attention to me. Though it was too fast for me to change camera position, I’ve never had such a good look at a swimming muskrat.

More exciting than seeing that swimming rodent was discovering an unusual climbing milkweed vine beside the paved walkway. The only time I’ve ever seen it in the wild has been in the company of botanist friend Pete Schubert, who is keen about these uncommon vines and has a talent for spotting them. He’s shown me several populations north of Durham on the Penny’s Bend natural area.

This one is anglepod, Gonolobus suberosus, because its milkweed-like fruit is smooth and distinctly ridged, giving it an angle-like configuration. Though it won’t jump out at you like the bearsfoot, the maroon and greenish-yellow nickel-size flowers are worth discovering. The long, distinctly heart-shaped opposite leaves help you locate the vine. Those unusual little flowers made my day!

As I headed back, the high-pitched call of a red-tailed hawk startled me from high above. I wondered what it was trying to communicate from its urban-wilderness tree-top perch.

Following the commotion from the hawk, I heard shouts of “water moccasin†from members of a young family exploring in the creek. I hurriedly stepped inside the forest to join the group, hoping to interrupt possible harm to an innocent creekside inhabitant. Sure enough, a young banded water snake was surrounded by two adults and four eager children. Once assured that they were observing a harmless water snake, they were content to watch it continue on its way.

What a full-of-surprises, adventure-filled walk that was along the greenway. I must remember to return frequently.

Baby seed pods of common milkweed are the result of successful pollination of the earlier flower clusters. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

It’s National Pollinator Week and we pause to honor pollinators. We should do it every week; that’s how important they are.

In addition to this Saturday’s Pollinator Celebration from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on the grounds of Chatham Marketplace in Pittsboro, plan a visit to the Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, anytime, to learn more about the importance of insects as pollinators.

Your museum visit begins on the outside. The half-block-long north side of the museum along Jones Street is a wild garden, a dramatic contrast to the lawn and shrub monoculture of the North Carolina legislature across the street.

The museum’s wild garden is, by design, an assemblage of native plants representative of the state’s botanical diversity from seacoast to mountains. Though many of the plants from far reaches of the state will not survive on the museum’s harsh north bank, some, surprisingly, do, like the native mountain bush honeysuckle, Diervilla sessilifolia, which occurs naturally only at very high elevations. I wonder that there may be some similarities between the harshness of the museum’s urban site and the extremes of high-mountain conditions.

That wild garden attracts a great diversity of wild critters. Several species of birds nest there and feast on the variety of seeds, fruits and insects associated with the native plants. Praying mantises hunt atop the flower heads of Joe-Pye weed, Eupatorium fistulosum. Common buckeye butterflies linger on the flower heads of rattlesnake master, Eryngium yuccifolium. Leaves of common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, provide sustenance for monarch butterfly larvae.

Museum curators frequently visit the wild garden to selectively harvest flowers, fruit and leaves to feed the living critters displayed inside. Most importantly, foliage, flowers and fruit and seed of the wildflowers, grasses and native trees and shrubs provide necessary food and cover for countless pollinating insects.

Folks walking by frequently pause to take closer looks at the color and movement in the wild garden. They express appreciation for such a different garden in the urban setting. But not all are so appreciative. On her way to work in the Legislative Building, a pleasant lady inquired, “Why does the museum have all those weeds?†I responded, “When those weeds are blooming, we call them wildflowers.â€

She lingered to explain to me how, growing up on a farm, her daddy always called those wild plants “weeds,†and the children had to help keep them away from the house to make room for the nicer cultivated plants.

When she noticed a butterfly weed, Asclepias tuberosa, she acknowledged that it made a pretty garden plant. Then she reflected on how her granddaddy took her walking in the woods and fields, talking about all sorts of wild plants. Some are good to eat, some make useful herbal medicines and some are just downright pretty. As she continued on her way, she acknowledged, “Well, all things considered, maybe we should all learn to appreciate those weeds.â€

After she left, I spied a mockingbird relishing the berries of pokeweed, Phytollaca americana, some unidentified warbler flitting about catching insects and butterfly larvae chewing milkweed leaves.

Then I appreciated that, largely unnoticed, the whole wild garden was alive with a host of insects visiting plants, unknowingly engaged in that vital function we call pollination. Thankfully, this action occurs every week.

Clusters of showy white stamens surround the single pistil of each cohosh flower. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Anne Lindsey – botanical researcher and teacher and co-author, with husband Ritchie Bell, of the second edition of Wild Flowers of North Carolina – has several of us asking that question these days about whatever flower we may be observing. Leading up to next week’s National Pollinator Week, Anne’s month-long series of N.C. Botanical Garden classes on pollination ecology is well timed.

Anne is making us aware that all those bees and wasps and beetles and ants and butterflies and all the rest are not flying about trying to attack humans. They are way too intent on finding pollen and nectar to survive to bother with us, unless we make motions to interfere with their nests. So before you reach for that can of insect spray, step back and take a closer look at what those insects are doing. Those insects we tend to dislike in our lives are playing a vital role in harmony with all the plants. Our lives are dependent on them.

When we do stop to think about pollinators, we most likely think of honey bees. As important as honey bees are, they are only a tiny bit of the pollination story. Thousands of native insects are the real pollinators upon which our whole way of life is dependent.

For example, hundreds of species of solitary bees alone go about their lives searching for pollen and nectar, and in doing so help hundreds of plants succeed in making seed to continue a collective vital role making our natural world function.

When I discovered black cohosh, Cimicifuga racemosa, coming into flower in the dark forest above the Eno River outside Hillsborough last week, I immediately became curious about what insects it needed to succeed. I didn’t linger long enough to make a scientific inquiry, but I was impressed with the antics of several big bumblebees hurriedly scurrying over the white flowering stems.

Along the flowering stem, clusters of showy white stamens (the male parts) surround the single tiny pistil (the female part) in the center of the flowers. Though other flying insects were visiting, none seemed to romp so aggressively over all the flowers as the bumblebees. I’ll give them credit for any pollination going on.

Flowering stems of cohosh can rise 6 or more feet above the broad dissected leaves. Photo by Ken Moore.

Black cohosh is an impressive summer wildflower of rich woodlands in the Piedmont and mountain regions. Candelabra-like flowering stems can reach higher than six feet. Sometimes you will see them stretching out for the light from dark forested roadsides. The much-dissected compound leaves can be a foot and a half or more wide, seeming to hover above the ground. I was surprised to find bumblebees in such dark environments.

Like so many of our native wildflowers, the black cohosh has a rich medicinal heritage. One described use of the herb was healing snakebite, thus the common name, black snakeroot. And like many an herb, the roots, soaked in moonshine, were used for rheumatism.

But don’t just look at the plant and flowers, remember to consider the pollinators and reflect how our very existence relies on them.

Though not a pollinator, the iridescent dogbane beetle depends on Indian hemp to survive. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

I have a new favorite plant, Indian hemp, Apocynum cannabinum, sometimes called dogbane because the milky sap is poisonous and is unsavory to dogs, who usually like chewing anything.

I featured it in Flora back in June of 2008 after being stopped in my tracks by the beauty of raindrops balanced on the paired leaves attached to the red stems.

Indian hemp was of great utilitarian value to Native Americans. No, they didn’t smoke it; they had better sense. They made use of the strong silky fibers of dried stems harvested in the fall to make cordage. Patiently weaving those silky threads by hand, the cordage products ranged from fishing line to strong rope, garments and moccasins. The dried and powdered roots were used for a number of medicinal purposes.

Next time you encounter the plant, or rather a stand of the plant (because, being rhizomatous, it makes great colonies), gently break off a leaf. You will observe a milky-white droplet at the breaking point. Be inquisitive and let a bit of that sap stick to a fingertip; after a few seconds, touch the fingertip with your thumb. Glue-like, it will tend to hold them together. Make certain you wash that sticky substance off and don’t dare taste it! Definitely don’t encourage children to play with it.

That sticky, milky sap must hold the secret to the strength of those fine silky fibers that became so useful to early Americans. There is great interest these days in reconnecting to the heritage of cordage; it has become a popular part of nature camps and outdoor environmental education programs. Even adults become passionate about it.

The reason I’m newly hooked on this plant is because of the diversity of flying and crawling critters it attracts. You can become mesmerized for long stretches of time. Though common along roadsides and fields everywhere, it’s easiest to examine the large colonies of Indian hemp in the fields of Mason Farm, where weekly walks bring weekly discoveries.

Countless insects and sometimes birds explore and settle on the surface of leaves and clusters of tiny white flowers. Some of those critters are pollinators, some are laying eggs on the host plant to serve the appetites of hatching larva and some are lying in wait to make a meal of unsuspecting others.

I couldn’t believe the beauty of the iridescent dogbane beetles, so plentiful a couple of weeks ago. There are a few still lingering. They hang around for only a couple of weeks, intent on mating and laying eggs on the undersides of the leaves. Hatching larvae bury into the ground and feed on the plant roots until emerging as adults next year. Beetle populations never seem too large to harm the plants.

The beautiful zebra swallowtail is frequently observed foraging on the short white flowers. They are obvious pollinators. Now I’m curious to observe which of all those other hovering critters may also be pollinators.

June 21-27 is National Pollinator Week. Celebrate the great diversity of pollinators with a walk to Mason Farm or some other field to check out all the action.

By Ken Moore

Had Gertrude Stein explored the forested edges of Carrboro or the wet ditches of Mason Farm Biological Reserve, she may have composed something like, A rose is pink is pink is pink!

Of all the roses growing wild in North Carolina, only two of them are truly native, both beautiful shades of pink. Though fairly common, the Carolina rose, Rosa carolina, and the swamp rose, Rosa palustris, are not likely to be found in ordinary rose gardens. Sadly, in the wild their singular beauty is seldom noticed.

The diminutive Carolina rose grows throughout the eastern United States. You will find it along dry roadsides and forest edges. There is a colony of them along the woodland edge of the N.C. Botanical Garden’s new parking area. They have already flowered, but look for rose hips developing a bit later.

If you have a keen eye, you may spot Carolina rose still in flower along the inner path of the Frances Shetley Bikeway behind Carrboro Elementary School. Look for it; there’s a plant identification label there. Once established, this little rose forms a colony from underground runners. It prefers dry, sunny situations. In cultivation, it performs vigorously. I once had a plant that established itself as a lush 3-foot-high thicket, and the shiny dark-green foliage and thorny red stems always made me take a closer, admiring look.

To find the swamp rose, you’ll almost have to get your feet wet. Like the Carolina rose, it is common throughout the eastern U.S. Unlike its cousin, it prefers to have its feet in the water. There are some robust 7-foot-high shrubs in the Siler’s Bog ditches along the south loop of the Mason Farm pathway.

And there are a few plants along the moist woodland edge of the Shetley Bikeway wild garden.

If you enjoy paddling coastal rivers and swamps, you will most likely discover robust 6-foot-high swamp roses commonly growing in the water at the bases of big cypress trees. Red rose hips are a certain giveaway during late summer and fall.

In addition to habitat differences, there’s another way to distinguish the two.

The thorns of the Carolina rose are almost perfectly straight. Swamp rose thorns are curved downward.

Carolina rose flowers are even a bit smaller than the 2-inch flowers of the swamp rose.

Though these two wild roses grow naturally in different habitats, they both take easily to cultivation. Just remember to allow them freedom to roam a bit.

They are worth seeking out at native plant nurseries.

Now is the time of year for the flush of their flowering, though sometimes there may be an occasional flower or two later on.

The beauty of these two roses represents for me the image of a perfect rose. I can imagine Gertrude Stein being content with a pink rose is a pink rose is a pink rose.

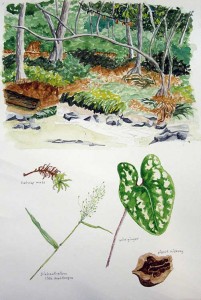

A moment in time at a Carrboro special place

By Ken Moore

What a surprise this past weekend to discover that the vast white penstemon fields of Mason Farm Biological Reserve came in second place to the mountain-like qualities of the Adams Tract section of Bolin Creek.

I had been looking forward to nature artist Robert Johnson’s Nature Notes Workshop at the N.C. Botanical Garden because it was scheduled to take place during the peak flowering of the tall white beardtongue, Penstemon digitalis.

The flowers were on schedule and the fields were spectacular.

In my estimation, those penstemon fields, in full flower, are as dramatic as any wildflower display anywhere, anytime, in the state of North Carolina. If you have not ventured out there for a viewing, you can catch the tale-end of their flowering. Perhaps a tardy visit will make you mark your calendar to see them at peak next year!

The 14 students, ranging from a high school junior and two university students to retired folks, keen on the outdoors, all enjoyed learning Robert Johnson’s ways of “being and seeing in nature†at both sites. It was Bolin Creek that really captured them.

The moss and lichen covered boulders and the melodic gurgling of the stream

made it all worth the uneven walk up through the pine forest and down through the oak-hickory forest to the edge of the creek. The setting charmed even Robert himself, who seemed transferred back to his mountain home at the base of Mount Mitchell.

Beginning at Wilson Park’s Adams Tract trailhead, the group stopped frequently to note characteristics of forest types, with eyes focused on little details like the common wild ginger, Hexastylis virginica; obscure, easy-to-miss Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria; and dozens of summer bluets, Houstonia purpurea, the many-flowered cousin to the single-flowered bluet or Quaker lady, Houstonia caerulea.

Robert had us all settle down along the creek, where we sat, eyes closed, for a good 10 minutes, with all our senses keenly focused on sounds, feelings and even the tastes of the air.

Then without a word, each student ventured off to find a spot from which to make a simple pencil sketch of the scene with a detail or two in a 6-by-8-inch pad. With reference to a small color chart based on 12 water colors, students made abbreviated color notes on their sketches.

Then back indoors at the Botanical Garden, under Robert’s guidance, students settled in to complete their sketches and details, adding color from their notes and keen memories of the place. While some returned to their penstemon field experience from the day before, most focused on the mountain-like experience along Bolin Creek.

The results were as spectacular as the outdoor scenes themselves. Some students were accomplished botanical illustrators, enthusiastic to discover a new way of viewing the outdoors; other students had never put pencil or brush to paper. Each set of images was beautiful and unique to the separate experiences of each beholder.

With pencil in hand is a great way to take a closer look and capture a certain unforgettable moment in time of a special place.

You know what? Every one of us can do it, if we simply try.

Endangered sandhills lily requires frequent fires to maintain its natural habitat. Photo by Mike Kunz.

By Ken Moore

This Friday is Endangered Species Day, when America celebrates our nation’s commitment to protecting wildlife on the brink of extinction (EndangeredSpeciesDay.org).

The N.C. Botanical Garden has scheduled three hour-long Endangered Species Day tours – 11 a.m., noon and 1p.m. – this Friday, beginning at the Gathering Circle in front of the Totten Center. No fee or registration is required. Just show up. Johnny Randall, assistant director for conservation and natural areas; Mike Kunz, conservation ecologist, and Andy Walker, conservation botanist will be available to show you endangered and rare species and they will describe the ways the Botanical Garden is involved with rare-plant research and protection and natural-areas management.

For example, staff and volunteers are propagating plants of endangered harperella, Ptilimnium nodosum, and planting them (reintroduction) back on their historical location on the Deep River in Chatham County.

Conservation ecologist Mike Kunz uses fire as a management tool for the health of some natural area. Photo by Johnny Randall.

Similarly, staff and volunteers are augmenting small populations of sandhillslily, Lilium pyrophilum, a recently discovered rarity of the sandhills.

Endangered species smooth coneflower, Echinacea laevigata, is being reintroduced to appropriate habitats within its historic range.

All of the above plant species are being propagated from plants of the original habitats to help insure the continuation of the natural diversity of the sites.

In cooperation with the N.C. Department of Transportation, a population of endangered roughleaf loosestrife, Lysimachia asperulifolia, was translocated from highway construction to a DOT conservation area.

Botanical Garden staff also manages approximately 900 acres of natural areas, many of which contain rare species, where eradication of invasive species and use of prescribed fires are some of the management tools used to protect natural-plant and animal communities.

In 1970, the Botanical Garden initiated the nationally honored “Conservation through Propagation†program to provide an alternative to wild-collecting. In 1979, it played a strategic role in establishing the N.C. Plant Conservation Program in the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. In 1984, it was a founding member of the national Center for Plant Conservation.

Other important organizations and agencies in collaboration with the Garden include The Nature Conservancy, NatureServe, N.C. Natural Heritage Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service and Botanical Gardens Conservation International.

The Endangered Species Day website describes 10 things to do at home to protect endangered species, including planting native plants and minimizing (best to eliminate) herbicides and pesticides.

Endangered Roughleaf loosestrife was successfully relocated from highway construction to a DOT conservation area. Photo by Mike Kunz.

I suggest we include another significant way to protect endangered species, and I include us humans in this category. If you did not participate in last Saturday’s “Great Unleasing†at Carrboro’s Century Center, you should become active with Transition Carrboro-Chapel Hill (transitioncch.org). Sign up to become involved with this group, the local body of a worldwide action group, committed to changing the way we work and live to meet environmental and economic challenges in positive, Earth-friendly practices.

Protecting endangered species begins with our own manner of living.

And celebrate the nature of our community by taking a walk at Mason Farm, where the Botanical Garden’s fire ecology management has resulted in acres of tall white beardtongue, Penstemon digitalis, in flower now!

By Ken Moore

I described bigleaf Magnolia, Magnolia macrophylla, last year (Flora, 7/16/09). The large leaves, arranged umbrella-like at the ends of the branches, create a tropical feeling in the forest landscape. There is a mature planted specimen overhanging Bill Bracey’s hillside patio in the heart of Chapel Hill.

Bill’s inspired placement of that tree is such that you can enjoy looking up through the whorls of giant leaves or down upon them from his hillside vantage point.

Viewing that tree this past week in full flower was another of those “oh wow†experiences. All in one plane was a three-day flowering sequence of about-to-open bud, a flower in early urn-shape phase and a third, wide-open flower.

What a show!

A good place to view bigleaf is in the northern section of Coker Arboretum near the grove of big cypress trees. It still has flowers opening way up high. At the N.C. Botanical Garden, you will find a nice specimen in the woodland garden behind the Totten Center. It still has buds and flowers lower down, offering a closer view.

This native magnolia has a curious distribution across the Southeastern states, from southern Ohio and southwestern Virginia down through eastern Tennessee, the central Carolinas, western Georgia and extending to Alabama, Mississippi, northern Louisiana and finally southeastern Arkansas. You are most likely never going to see it in the wild, though occurrences continue to be documented by botanists.

Every time I see Bill’s bigleaf magnolia, I realize I have let another year pass without planting one of my own.

Fortunately, keen plantsmen keep propagating this magnificent tree, so it is sometimes available in nurseries and garden centers. Camellia Forest Nursery west of Carrboro still has some small ones, good sizes for successful planting this time of year. If your favorite nursery doesn’t have bigleaf, ask them to get some.

While admiring bigleaf, I reflect on how the magnolia is a very primitive plant family; it’s been moving around on this land for a long, long time.

Then I reflect on its close relative, the common tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, also flowering now, with its small green and yellow tulip-shaped flowers so high on the tree we usually miss seeing them, unless finding fallen ones underfoot.

And then I think of Davie Poplar, that ancient tulip-tree, under the shade of which legend describes the university’s founding fathers making their decision to site the future university right here more than 200 years ago.

And then I am reminded of that fine exhibit “Noble Trees, Traveled Paths: The Carolina Landscape since 1793†in Wilson Library’s Carolina Collection Gallery through May 31.

Bigleaf flower has three impressive stages: (left to right) bud, upright vase-shape and wide-open horizontal. Photo by Ken Moore.

With most of the students on summer leave, now is a good time to find access to this exhibit. It’s more than pictures of old trees. Exhibit curators Linda Jacobson and Bill Burk have weaved a memorable story of the rich natural and human heritage of this place we call home. It is sad the exhibit cannot remain permanently. It deserves publication as a small guide to campus heritage.

Don’t miss seeing it!

And don’t miss seeing bigleaf in flower, and planting one of your own.

By Ken Moore

Last week, I saw calamus root, Acorus calamus, growing wild on the edge of town in an open field with a spring flowing from the base of a big tree making a wet meadow habitat, ideal for calamus root.

Also called sweet flag, the foliage resembles the fan of flat, narrow leaves typical of blue flag irises, thus the name sweet flag. Calamus, a useful herb, is sweet tasting, while irises are poisonous. You definitely do not want to confuse the two!

Betsy Green Moyer’s photograph in Paul Green’s Plant Book was captured at the N.C. Botanical Garden. Though lacking flower petals, with a closer look the calamus flower spike is strikingly beautiful. It’s similar to Jack-in-the-Pulpit, without the hooded wrap-around sheath.

Paul Green describes sweet flag as helpful for stomach troubles and colic. It’s also reputed to be a fine stimulant, valuable for liver health and smoking cessation.

I love Green’s story “Too Late for Old Miss Minty.†The story goes: “I remember old Miss Minty who used to come and stay with us on a visit, how she would carry some sweet flag root wrapped up in her old handkerchief. And sometimes as she sat by the winter fire, she would take out the root in her trembling hands, break off a piece, put it in her toothless mouth, and sit there sucking it and staring peacefully at the fire. The root was supposed to be good for the preservation of the teeth and as an aphrodisiac, though too late to do old Miss Minty any good in either case.â€

I’ve learned from local herbalist and wildcrafter Will Endres at the Carrboro Farmers’ Market that calamus is an esteemed herbal plant. He has been working on a book all about calamus and plans to have it published later this year.

I went by the market this week to share with him my excitement about seeing it for the first time in the wild. Since he was busy with other folks, I engaged his son, Sean, himself an experienced herbalist and wildcrafter. I was impressed when Sean pulled a good-sized piece of calamus root from his pocket. He described that he chews a bit of it before cross-country races, using it like the Native Americans for long-distance endurance. Sean likes the name “singer’s root,†attributed to its value for voice projection and preventing laryngitis.

When I checked on calamus in the current taxonomic authority, I discovered that the one we find in North Carolina is the European calamus, brought over by the first European settlers. American calamus, Acorus americanus, though widespread throughout northeastern America, is not well documented, so botanists are keeping a keen eye on finding new populations of both species. The leaf of the more common European calamus has a very prominent, raised mid-vein along the middle of each leaf. The leaf of native calamus is smooth to the touch.

Calamus is in flower right now, so be certain to take that closer look when exploring open wet habitats, and remember not to confuse calamus with poisonous iris.

By Ken Moore

“I thought I’d died and gone to heaven!†That’s an expression I learned years ago to describe anything wonderful beyond description. Seeing acres and acres of yellow pitcher plants, trumpets, Saraccenia flava, flowering on the inner ring of a pond cypress, Taxodium ascendens, swamp, is definitely such an experience.

Three lucky couples from Carrboro and Chapel Hill joined Robert (Muskie) and Vikki Cates for a paddle on Horseshoe Lake in Suggs Mill Pond Game Land southeast of Fayetteville two weeks ago.

Muskie and Vikki paddle a lot. Muskie plans his trips well in advance and he has objectives, like on this last one: “I think we’ll catch the pitcher plants in flower.†He was dead on target. In all my years of botanizing in wild places, I’ve never seen anything like this! Thousands of yellow-flowered trumpets on floating mats of sphagnum moss encircling Horseshoe Lake were a died-and-gone-to-heaven surprise.

Paddling on that horseshoe-shaped Carolina bay lake was like stepping way back in time to experience wild nature before humans had progressed very far. And there are hundreds of Carolina bays scattered across the coastal plain.

Carolina bays are curious elliptical-shaped configurations, all with a northwest to southeast orientation. These distinctively shaped landscapes are easily identified on satellite photos. Most of them are densely vegetated evergreen shrub bogs or bay forests. A few, such as Singletary Lake and Jones Lake, are still open water, bordered by swamp or bay forests. Horseshoe Lake’s distinguishing horseshoe shape results from vegetation slowly filling into the lake center from the northwestern end.

Many theories have been proposed for the origin of the Carolina bays, from a giant dinosaur-age meteor shower to underwater wave action back when ancient seas covered the land. The engaging debate continues to this day.

Carolina bay evergreen shrub bogs and bay forests are characterized by a couple of dozen mostly evergreen trees and shrubs that, in the absence of flowers, can be a challenge to identify. Some of our fine garden plants like sweet bay magnolia, inkberry holly and Virginia willow come from this assortment of plant communities.

These wild areas are interesting to explore, and spectacular gardens are frequently found in sunny transition zones, particularly along the edges of the lakes, such as we found at Horseshoe.

After flowering, the two-foot-tall trumpet leaves will be spectacular all around the lake during the growing season. I’d like to be paddling there right now to see extensive mats of bladderworts, Utricularia spp., with tiny yellow flowers held a couple of inches above the lake surface. A few weeks later, that same lake surface will be covered with thousands of native white-flowered water lilies, Nymphaea odorata. All definitely worth a paddle!

If you don’t have a trip planner friend like Muskie, it’s not too difficult to plan your own natural gardens exploration. Check out Exploring North Carolina’s Natural Areas, edited by Dirk Frankenberg. It contains specific descriptions with suggested field trips for numerous natural areas throughout the state.

Whether driving, walking, biking or paddling, nature’s gardens are worth the effort!