By Ken Moore

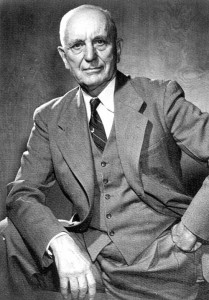

William L. Hunt (1906-1996) introduced me to botany and horticulture when I began a master’s program in English here at UNC in 1962. Billy, as many of his contemporaries affectionately called him, grew up in his uncle’s Greensboro nursery. He was already an accomplished gardener when he arrived in Chapel Hill with a truckload of irises and other plants in 1927 to pursue a botany degree under W.C. Coker and Roland Totten.

He remained here for the rest of his life, growing native and exotic plants, lecturing throughout the Southeast and writing a weekly garden column. Though he was well known as a horticulturist, his real love was the study and growing of our native flora.

I vividly remember a late-April day in 1968 when Mr. Hunt took me to view an atamasco lily meadow north of town. I’ve never seen such a field since. He said that Eastgate Shopping Center and other low-lying developments were once lily-filled wet meadows.

Recently, while surveying some of Mr. Hunt’s archives, I discovered a copy of the January-February-March 1938 issue of The Gardener, published at Pocha’s Horticultural Press, Poona, India, for the avid-gardening public of that faraway land.

In that little publication was a short article, “Atamasco Lilies,†by William L.

Hunt, which I want to share with you. A black-and-white photograph of one of our local lily fields filled half the page.

“One of the truly breath-taking sights in the Piedmont and Coastal regions from Virginia south, is to be found in certain meadows where the ‘Atamasco Lilies,’ Zephyranthes atamasca, abound. These members of the Amaryllis family are very easily cultivated, and will grow, quite accommodatingly, even under conditions somewhat different from their natural habitat of swamp of ‘Crawfish Land.’…

“They seem to put up with almost any conditions, so long as their requirements of moisture in Spring and a somewhat rich diet are supplied.

The wettish parts of gardens suit them best of all.

“The last week in April finds them in full flower in North Carolina. Each clump of bulbs sends up from five to 10 flowers, one after the other, in rapid succession, and a whole meadow of them is worth going many a mile to see.â€

Sadly, nowadays we see only remnants of those extensive former meadows, a plant or two still surviving in shady, wet woodlands and forest edges.

Surprisingly, atamasco lily is the N.C. Botanical Garden’s Wildflower of the Year for this year. You can get a free packet of seed from the garden. Better yet, visit the garden’s plant sales to get one or more plants grown from seed.

It takes a lot of seeds to provide for Wildflower of the Year, and the garden staff is indebted to a generous local family for sharing seeds from their horse-pasture meadow of thousands of atamasco lilies – a lingering, living heritage of an earlier time, when such lily fields were a common sight. Horses and deer won’t eat atamasco lilies!

This lily field, now a rarity in our area, is approaching peak flowering, and I’m going out to view it. You’re welcome to join me if you’re willing to carpool. Meet me at the rear of the Eubanks Road Park-and-Ride Lot at 10 a.m. this Saturday. As Mr. Hunt said, “a whole meadow of them is worth going many a mile to see.â€

By Ken Moore

Recently, I attended Janie and Stewart Bryan’s celebration of the annual flowering of their big redbud. On the short drive west of Carrboro, I was admiring all the redbuds growing naturally along the forest edges.

I reflected on how much I prefer the two-plus weeks of redbud flowering to that earlier, less-than-a-week flowering of the Bradford pears, that are ubiquitous in shopping malls and along residential streets. You may detect my annual Bradford pear tirade.

It’s been several years since I’ve seen the magnificent redbud gracing the corner of Janie’s and Stewart’s home; I had forgotten how impressive it is.

When I suggested that it must certainly rank up there with the state champion, we went to the computer to find out where the state champion redbud actually resides. (dfr.state.nc.us)

The currently listed champion eastern redbud, Cersis canadensis, is located in Forsyth County. And guess what? That champion may be in for a real challenge! The measurements (circumference, height and spread) of our local specimen seem to surpass those of the current champion. The statistics have been forwarded to the state-champion tree folks for an official determination.

I hope I can report a new champion sometime in the near future.

Meanwhile, just reflect back on what a magnificent redbud flowering season we continue to have, in spite of the recent summer heat wave. The mini-heat wave didn’t seem to alter redbud flowering, but it did hasten the emergence of dogwood leaves. The usual dazzling white of flowering dogwood, Cornus florida, is camouflaged this spring by the flush of fresh green foliage. However, even in its subdued form, the long period of dogwood flowering, overlapping with the redbud, and with yellow sassafras, Sassafras albidum, tucked in between, provides us with a month-long springtime display of our common Piedmont native flora, a yearly gift from nature.

This may be a stretch for some of you, but I’m concerned about these trees. I look into the future and I wonder, are we going to witness future rarity of these beautiful common native plants?

The reason I worry is because of Bradford pear, that horticultural wonder introduced onto our landscape a couple of decades ago. So wildly popular it is that it’s still being thoughtlessly planted everywhere. Birds love the fruit and drop the seed of those digested fruit far and wide to germinate all along bird flyways. During their very short flowering period, Bradford pears are now easily detected all along our roadsides and into adjacent forests.

Three weeks ago, I visited several formerly open-field sites adjacent to hotels and office buildings in the vicinity of Research Triangle Park. Those fields were 75 percent or more vegetated with Bradford pears, displacing native species like redbud and dogwood. Those pears from the adjacent commercial landscapes are escaping big time. To me, viewing such a sight is not pretty; it’s downright scary.

That’s why I worry about redbuds and other native trees. I want to go back and sit under Janie’s and Stewart’s big redbud, where there is not a Bradford pear in sight.

Former UNC President Kemp Plummer Battle (1876-1891) beside newly planted Davie Poplar Jr. in March 1918. Davie Jr. now stands tall and proud between Davie Poplar and Davie Poplar III. Photo from North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.

By Ken Moore

Most folks are familiar with the 200-plus-year-old tulip poplar Liriodendron tuliperifera, affectionately known as the “Davie Poplar.†It lives in the center of UNC’s McCorkle Place, the campus quad between Franklin Street and South Building. It was beneath that singular tree that legend credits the founding fathers’ selection of the site for the state’s university.

Davie Poplar contemporaries still standing include a mighty double-trunked male American holly, Ilex opaca, a former state champion post oak, Quercus stellata, and a statuesque persimmon, Diospyros virginiana.

To honor these noble trees and hundreds of planted specimens on the UNC campus, the university has published an 80-page guide, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s NOBLE GROVE: A walking Tour of Campus Trees. It’s available at Student Stores and the N.C. Botanical Garden’s gift shop.

The guide describes four walks encompassing the four main quads of the campus. The descriptions of 100 specimen trees include original forest giants, newly planted native and exotic species and cultivars, with line illustrations by Bonnie Dirr. The text by Michael Dirr, nationally known horticulturist and professor emeritus of horticulture at the University of Georgia, provides specific references to cultivars suggested for landscape use and facts about size and location of national-champion relatives of significant campus specimens.

Mike Dirr will be on campus April 22 for a “walk and talk†celebrating UNC’s trees. The walk, beginning at the front steps of Wilson Library at 3:30 p.m.., is free; no registration required. A reception and viewing of the special exhibit, “Noble Trees, Traveled Paths: The Carolina Landscape Since 1793,†follows in Wilson at 5:00 p.m. Mike’s talk, this year’s Gladys Hall Coates University History Lecture, follows at 5:45 p.m.

The engaging exhibit of text, illustrations and photos, describing the evolution of the campus landscape and the many people who played significant roles in that evolution, continues through May 31, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturdays and 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays in Wilson’s North Carolina Collection Gallery.

One text panel from the exhibit:

“To Have a Good Influence upon the Manners of Young Menâ€

Letter (facsimile) from Elisha Mitchell to Trustee Charles Manly,

December 27, 1849.

In the letter below, Mitchell, in his role as University bursar or business officer, notifies Manly of improvements made to the grounds in the years from 1847 to 1849. Of particular interest is the expectation that well-manicured grounds will improve the manners of the students:

“The improvements extending over a large space do not make a great show at any particular spot, yet a good deal has been accomplished and the heaviest part of the work done. The giving of some grace and beauty to the approaches

This former state champion 200-year-old post oak still stands proud near Person Hall on the UNC campus. Photo by Ken Moore.

to the buildings and to the walks around them is supposed to have a good influence upon the manners of the young men and to impress strangers favorably.â€

Don’t miss this opportunity to take a “closer look†at our people/plant heritage.

Discovering the fire pink in Ohio in his high school days led B.W. Wells on a lifetime pursuit of botanical studies in North Carolina. Photo by Tom Wentworth.

By Ken Moore

In 1932, The Natural Gardens of North Carolina, written by Dr. Bertram Whittier (B.W.) Wells, professor of botany at N.C. State University, was published by the University of North Carolina Press. How well I remember back in 1966, my mentor presenting me with a copy of Natural Gardens with the comment, “If you are going to study the botany of North Carolina, then you need to become acquainted with B. W. Wells!†That began for me a lifelong pursuit of discovering and enjoying the natural gardens of our state.

As a high school freshman in Ohio, Wells, with the help of a plant key, saw and identified a fire pink, Silene virginica, a brilliant-red wildflower we see here in early May. He later described that experience: “From that moment on I knew what my life’s work would be. I was so terribly excited about identifying that flower.… The more you see, the more you have to see.â€

Wells received his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago and in 1919 accepted an appointment at what was then N.C. State College, where he remained as head of the botany department until 1949 and a professor until 1954.

He was inspired and challenged by the beauty and diversity of North Carolina

plants and plant communities. An engaging teacher and a competent researcher, Wells made great contributions to the new discipline of plant ecology. For him, the diversity of seasonal wildflower displays in distinct plant communities across the state were, indeed, spectacular natural gardens. He was an excellent communicator and writer. Natural Gardens, republished by UNC Press in 1996, is a very readable description of the state’s natural vegetation, from the ocean spray dunes to the high-mountain evergreen forests.

Some of Wells’ notable observations include salt-spray effects on dune vegetation, a possible meteorite origin of the hundreds of elliptical-shaped Carolina bay lakes and bogs in the coastal plain and Native American burning practices as a possible origin of high-mountain grassy balds. He encouraged nurserymen to propagate the great variety of native plants for home-garden and urban-landscape use. He was way ahead of his time!

In retirement, Wells remained physically active, farming an old homestead, Rock Cliff Farm, above a dramatic bend of the Neuse River near Wake Forest. When not engaged in farm work or laying out walking trails through his natural gardens, he painted with water colors, oils and pastels, over 100 beautiful portraits of the state’s natural gardens, including his own farm.

With support from the B.W. Wells Association, Rock Cliff Farm is now preserved as part of the Falls Lake State Recreational Area. The farm, including his self-built artist studio and miles of trails, are not generally open to the public, so B.W. Wells Heritage Day this Saturday is a great opportunity to visit. Refer to bwwells.org for directions and descriptions of day-long activities, including wildflower, geology and heritage farm tours and special activities for children.

As I was counseled years ago, if you want to appreciate the real “nature†of our state, you need to become acquainted with B. W. Wells and The Natural Gardens of North Carolina. Some of those natural gardens are at Rock Cliff Farm. “The more you see, the more you have to see.â€

By Ken Moore

At the base of the utility pole on the Weaver Street Market corner of Weaver and Greensboro streets is a beautiful little garden of speedwells and dandelions and other close-to-the-ground, early-spring flowering weeds. There are several of these miniature gardens scattered beneath the big post oaks at the corner.

Signaling spring’s arrival, those blue speedwells are flowering now in many yards throughout our neighborhoods. You may even spot patches of blue in the medians as you drive around our towns on Fordham Boulevard.

You may also have them in your yard, but you may move too quickly to enjoy them and the diversity of other flowers scattered there. But if you have one of those turf-grass lawns, regularly maintained with fertilizers and herbicides, you won’t have a spring-flowering yard.

To have such a yard, you must set about to cultivate a “freedom lawn.†Such a lawn is not really too much of a challenge to create and maintain. To succeed, all you have to do is nothing. Your yard will become filled with all sorts of volunteer plants. In flower now is an assortment of winter annuals that begin growing in the late fall and burst forth with flowers close to the ground in early February. Flowering close down on the ground seems to be an advantage during cold weather.

You may have to get down on hands and knees for some “belly-button botany†observations to appreciate the floral display. My truly favorite of all the many early-spring yard flowers is the beautiful little speedwell, Veronica persica. Hundreds of blue flowers greeted my downward glances as I was hanging out the laundry in my yard a couple of days ago. I never cease to be humbled by the clean beauty of this quarter-inch broad, four-petal flower when examined at close range.

Another of my favorites is the lowly common chickweed, Stellaria media. This bane of the lawn perfectionist can shine up at you like hundreds of little bright stars speckled across a bed of pale-green foliage. Close observation of the tiny quarter-inch-diameter flowers will reveal five pure-white petals that are split like rabbit ears, appearing to be 10 petals. Gently pull one double petal away from the flower to enjoy the tiny white rabbit ears in the palm of your hand. I can’t resist doing that!

Rather than curse the lowly chickweed, being a lazy, carefree gardener, I simply let this early-spring annual romp around on the yard and through garden beds. The tender foliage makes a tasty addition to salads and it is a special treat relished by parakeets. By late spring, it’s gone, out of sight, until the next winter.

Another lawn weed is the purple dead nettle, Lamium purpureum. Sometimes in my yard, low clumps of these plants seem to join together and move like waves of pinkish flowers across the wild landscape. Upon close observation, each flower makes me think of a turtle head reaching out from beneath those leafy bracts to sniff the warming air.

Speedwell, chickweed and dead nettle accompanied the Europeans to North America long ago. I enjoy having them romp around the yard early in the spring ahead of the larger garden flowers.

Grand old oak across from Town Hall most likely witnessed the naming of Carrboro. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

The rights of trees were important to geologian Thomas Berry (1915-2009), who described his thinking about human activity on Earth in his book The Great Work. Recently, the Center for Ecozoic Studies (ecozoicstudies.org) convened a gathering in Chapel Hill of over 100 people to learn more about Berry’s works and philosophy. What a comfort to be in the midst of kindred beings so in touch with the nature of the Earth we all share.

Berry’s view of our current reality is stark. “The most basic and most disturbing commitment of the original European settlers was to conquer this continent and reduce it to human use.… Just now we seem to be expecting some wonderworld to be attained through an ever-greater dedication to our science, technologies, and commercial projects. In the process, however, we are causing immense ruin to the world around us.â€

The continuation of human “business-as-usual†activities will rapidly lead, in Berry’s estimation, to a cataclysmic change on Earth not experienced since the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. He sees us now approaching the end of the intervening Cenozoic Era and destroying in only a couple hundred years much of the magnificent biodiversity that evolved during that 65-million-year period.

Being positive, he also sees the possibility of a new period, “an Ecozoic Era, a period when humans become a mutually beneficial presence on the Earth. That future can only exist when we understand the universe is composed of subjects to be communed with, not as objects to be exploited.â€

Acknowledging that, “We cannot own the Earth or any part of the Earth in any absolute manner,†Berry places our human rights, so self-centeredly described in our nation’s Bill of Rights, in the context of all beings (“subjectsâ€) in the universe having rights. “Trees have tree rights, insects have insect rights, rivers have river rights, mountains have mountain rights.â€

For me, the giant trees in our community symbolize at once the wonders of our environment, the stark realities of human destruction and the potential to reverse our destructive habits that are all so engagingly described in The Great Work.

That giant willow oak shading the yard directly across from Carrboro’s Town Hall makes me pause in the knowledge that it probably stood there prior to the town being officially named Carrboro in 1913. I’m happy it has been allowed the right to remain.

I marvel even more at the curbside survival of those big oaks on West Franklin Street, dreading the time when their right to live and thrive may be taken by streetscape beautification working its way westward.

Whether walking in town or on forest trails, pause and ponder how our human interests so often and so quickly remove such giants from our landscapes. We have a long way to go before our trees and all other “subjects†of the Earth have the rights we humans hold so dear for ourselves.

West Franklin Street oaks are impressive and deserve appreciation each time you walk beneath one. Photo by Ken Moore.

Only four weeks remain before trees become hidden by massive green canopies, so take several walks before winter is over and honor those big trees while they are easy to see. If you dare, stand looking up into the bare canopy of any of them and consider what rights you are willing to share with a tree.

By Ken Moore

Last week, I admired sycamore balls dangling from a young tree at the northeast corner of the YMCA parking area.

Also last week, Botanical Garden director Peter White shared a digital image of mounds of tawny-colored fluff, sycamore seed, assembled in irregular patterns by the rain running along the curb of his usual Carrboro-to-campus bicycle commute route. During his daily commutes, Peter has become a keen observer of curbside botany. Observing organic debris that accumulates along drainage ditches and gutters offers engaging “what’s that?†puzzles as well as clues to nature’s seasonal actions.

Closer examination shows that the fluff is an accumulation of hundreds of tiny seeds, each seed attached to a plume of fuzzy hairs that, when dry, lifts each sycamore seed far and wide on wind currents.

As described in the Jan 8, 2008, Flora, the mighty sycamore (Platanus occidentalis.) is easily identified by the white color of its upper trunk, easily seen from a distance, particularly in the winter months. The lower trunk of the tree is recognized by contrasting brown and green exfoliating bark. It can’t be confused with any other North Carolina tree. It normally occurs in river bottoms, but is frequently seen in urban areas, because, like other river-bottom trees such as river birch and willow oak, it tolerates harsh urban conditions.

The smooth sycamore balls are fun to compare with the spiky sweetgum balls described in last week’s Flora. Balls of both trees are similar in that they hang on long cord-like peduncles at the ends of tree branches and both are having a major drop during this early spring season. Though the spiky sweetgum balls are dropping now, they dispersed their seed back in the fall.

Sycamore balls are made of countless hairy-plumed seeds that seem to be glued together. The ends of the seeds form the surface of the ball. It is nature’s wisdom that now is the time for sycamore seeds to be dispersed. You will often find flattened clumps of seed fluff on the ground beneath the big trees. You may get a glimpse of the seeds flying above, singly or clustered, or you may be lucky to witness one of those hanging balls suddenly explode to release a cloud of fluffy seed to be carried aloft.

Following the release of the seeds from that sycamore ball, you may find a smaller ball still hanging. That is the very hard core that was commonly used by Native Americans and pioneers for shirt and jacket buttons. If you have an opportunity to examine one close up, you will be impressed by how hard that little center core is, and by the durability of the attached stem, the peduncle, by which it was attached to the tree.

The spiky sweetgum ball differs from the sycamore ball. From left to right: spiky sweetgum ball (notice a few tiny seeds in upper left); intact sycamore ball, seed ends making the outer surface; sycamore ball exploded, displaying numerous hairy plumed seeds; the inner hard core, a pioneer’s button, still attached to the twig. Photo by Ken Moore.

A good place right now to compare the balls of both trees is below the playground area of Carrboro’s Wilson Park. There are great specimens of both trees with balls on the ground and hanging aloft.

While taking a closer look, pause and wonder how those tiny seeds can become such giant trees, and be awed at the natural mechanism that holds onto those seeds and then disperses them so opportunistically.

Folks like Sue Morgan and her family enjoy dramatic features of nearby Occoneechee Mountain. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

Recently, D.G. Martin, columnist for The Chapel Hill News, described his list of seven natural wonders in North Carolina. D.G.’s descriptions inspired my thinking about our local natural wonders.

Some of you spend an hour or two each week walking along a favorite woodland trail. I wonder how many of you choose a different trail each week. There are so many great walks close by that my wife, Kathy Buck, and I often have difficulty choosing one.

Sometimes wide-open spaces are appealing; other times, secluded shady coves. There’s quiet warmth in stands of green needle-floored pine forests; in contrast is adventure climbing to the heights of giant oak crowned ridges.

Special trees beacon, like the twisty old chestnut oaks and mountain laurels of Occoneechee Mountain State Natural Area, the giant oaks of Big Oak Woods of Mason Farm Biological Reserve or the big loblolly pines in the Adams Tract.

Already I’ve listed three of my favorite local natural areas: #1, Occoneechee Mountain (enoriver.org) overlooking Hillsborough; #2, N.C. Botanical Garden’s Mason Farm, south of Finley Golf Course; and #3, Carrboro’s Adams Tract, extending from Wilson Park up and over and down through mature pine and oak-hickory-beech-maple forests to Bolin Creek.

Continuing my list of local natural wonders is #4, Carolina North, some 750 acres of diverse woodlands bordering the Bolin Creek corridor with miles of trails maintained by UNC (fac.unc.edu/Carolinanorth).

My #5 is Duke Forest, 7,000-plus acres of diverse forests between Durham, Chapel Hill-Carrboro and Hillsborough. You can walk a different trail every week for three months. Duke’s forests (dukeforest.duke.edu) include natural features like rhododendron bluffs along New Hope Creek as well as demonstration areas of forest management practices.

My # 6 is the 93-acre Battle Park forest stretching from Forest Theatre on UNC campus to Chapel Hill’s Community Center. Trails in this historic forest are managed by the Botanical Garden and maps are available at several trailheads. (ncbg.unc.edu)

Another favorite, # 7, is Triangle Land Conservancy’s Johnston Mill Nature Preserve (triangleland.org), between Chapel and Hillsborough. Trails course through mature pine and deciduous forests along New Hope Creek and meander over higher ground featuring an unusual elfin forest of American beech.

There are others. I hope that some of you will take time to share with readers (editor@carrborocitizencom) descriptions of your favorite local natural treasure.

The winter beauty of open fields surrounding Mason Farm’s Big Oak Woods is prelude to colorful wildflowers in warmer months. Photo by Ken Moore.

Most importantly, be appreciative of our natural treasures; some of the features, like laurel bluffs, are relicts of the ice age. Support the organizations that protect and manage them and explore all of them.

By Ken Moore

Over the years, I’ve enjoyed collecting witch’s brooms. Well, now, I haven’t actually collected them; I’ve merely spotted them, and revisit them often, quite often, since most obvious ones are along roadsides.

They are like old friends, and I smile inside every time I pass one.

My favorite witch’s broom is a fine specimen perched midway up a scrub pine, Pinus virginiana, along Estes Drive Extension between Chapel Hill and Carrboro.

Just before the holidays, I spotted one midway up a loblolly pine, Pinus taeda, along the ramp from Smith Level Road onto the U.S. 15-501 bypass. Can’t believe I had never noticed it; guess I’ve been paying more attention to vehicles on the road – not a bad thing. “Witch’s broom spotting†should not become a cell phone-like distraction while driving.

Last week, I spotted another one in a loblolly pine while walking through the pine forest of Carrboro’s Adams Tract.

A witch’s broom is an abnormal growth in a tree, usually caused by a virus or fungus. The growth is a dense mass of shoots growing from a single point, resembling an old-timey broom or strange-looking bird’s nest. There is not a lot of information on what is really going on with this plant-growth curiosity. I suspect there is simply not enough interest or concern for any young botanist to pursue a doctoral study.

I share my witch’s broom sightings with botanical garden nursery manager Matt Gocke, who is hoping to propagate some interesting-looking trees from some of the brooms. One way of producing plants with the compact, dwarf characteristics of witch’s brooms is to make grafts of the broom branches, or “scions,†onto the stems, or “stocks,†of normal-growing plants of the same species.

If the witch’s broom produces cones, then another possibility is to grow a dwarf tree from a seed collected from that abnormal growth. One such oddity is a dwarf loblolly pine growing along the north walk in the Coker Arboretum. That one is a dwarf seedling from a magnificent witch’s broom high up in one of the arboretum’s big pines. Sadly, that tree was killed by lightning two years ago. On your next walk through the arboretum, look for curator Margo McIntyre or one of her assistants to help you find that dwarf loblolly.

These rare curiosities are most frequently spotted in pine trees, though I did find one in a red cedar, Juniperus virginiana, several years ago.

More commonly spotted are the witch’s brooms in hop hornbeams, Ostrya virginiana, easily observed in winter months, when the messy looking, dense, leafless twig structures can be quite numerous on a tree, giving it a truly “bad-hair day†look. There are lots of them along the trail encircling Big Oak Woods at Mason Farm Biological Reserve.

Folklore is filled with stories of witches and their flying about on coarse twiggy brooms. I like the story of witches flying over trees to make brooms grow in them. I enjoy thinking about that story when walking beneath all those witch’s brooms in the Mason Farm hop hornbeams.

It’s fun to look up into trees; never know what you may find there!