“Speed the Plow” (sometimes “Speed the Plough” or

“God Speed the Plough”) is a well-traveled tune, popular with fiddlers for over

200 years. Although it is considered a ‘chestnut’ in many circles, it has a

deserved place in core fiddle repertoire in several genres, for it seems to

flow off the fiddle yet is melodically interesting in both its parts. The reel is extremely widespread in

English-speaking traditions and can be found in the repertories of fiddlers

throughout North America, Ireland, Scotland and England. What is most unusual

is the fact that we do know who composed “Speed the Plow,” unlike many older

tunes whose origins are typically unknown. Captain Francis O’Neill researched

the melody and reported his findings in Irish

Minstrels and Musicians (1913), basing his remarks on entries from the British Musical Biography. Therein he

found that the reel was the work of one John Moorehead (whose name has also

been given as Morehead or Muirhead), of County Armagh, Ireland. Moorehead was not Irish originally, but was

born in Edinburgh and emigrated to Armagh in 1782. He was from a musical family

and had copious talent on the violin, gaining such renown that  he became violinist for

London’s Covent Garden Theatre in 1798. It was the year after this appointment

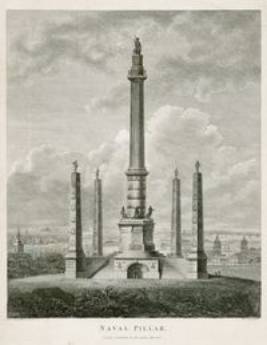

that he penned his famous reel, originally entitling it “The Naval Pillar” in

support of a proposed memorial column of that name to have been erected in

London to commemorate Lord Nelson’s recent headstrong victory over the French

in the Battle of the Nile in 1798.

Moorehead lived to see his melody become a popular success, although he

unfortunately later committed suicide by hanging in 1804. The violinist’s

melody was employed by the English dramatist Thomas Morton (1764-1838) for his

‘comedy’ Speed the Plough (it was

actually much like a melodrama, although the term had not been invented then),

written and staged in the year 1800, and associations with this play resulted

in the reel becoming popularly and fixedly known as “Speed the Plow.” [When the

play crossed the Atlantic and was produced in Boston it starred the thespian

parents of poet Edgar Allen Poe, who garnered good critical reviews for their

efforts, although the play itself was received lukewarmly].

he became violinist for

London’s Covent Garden Theatre in 1798. It was the year after this appointment

that he penned his famous reel, originally entitling it “The Naval Pillar” in

support of a proposed memorial column of that name to have been erected in

London to commemorate Lord Nelson’s recent headstrong victory over the French

in the Battle of the Nile in 1798.

Moorehead lived to see his melody become a popular success, although he

unfortunately later committed suicide by hanging in 1804. The violinist’s

melody was employed by the English dramatist Thomas Morton (1764-1838) for his

‘comedy’ Speed the Plough (it was

actually much like a melodrama, although the term had not been invented then),

written and staged in the year 1800, and associations with this play resulted

in the reel becoming popularly and fixedly known as “Speed the Plow.” [When the

play crossed the Atlantic and was produced in Boston it starred the thespian

parents of poet Edgar Allen Poe, who garnered good critical reviews for their

efforts, although the play itself was received lukewarmly].

O’Neill was tempted to claim the melody as Irish,

probably partly on the strength of Moorehead’s Armagh connection. Writing that

he thought the tune was “Irish in character,” he eventually ‘regretfully’

concluded he could not in good conscience include “Speed the Plow” in his Dance Music of Ireland (1907) because of

its association with the English stage.

The tune spread with incredible rapidity for the

time, and it seems as if overnight it had spread throughout Great Britain, the

British colonies and former colonies. Perhaps as evidence of one mode of

transmittal, one of the earliest notations of the tune (under the title “Speed

the Plough”) appears in the music-manuscripts of William Litten, a

square-rigged ship’s fiddler originally from England whose copybook dates from

the very first years of the 19th century. Around the same time the title appeared in Henry Robson’s Northern Minstrel’s Budget, a listing of

tunes and songs popular in his home region of Northumbria. Robson published his

list around the year 1800, indicating how quickly it had spread northward. By

the mid-19th century, the melody had appeared in numerous printed

tune collections and in fiddlers’ manuscripts.

In America it was, for example, included in George P. Knauff’s Virginia Reels, volume I,

printed in Baltimore in 1839, and in the mid-century publications of Elias

Howe, such as his huge Musician’s Omnibus (1864). “Speed the Plough” appears

in the 1840’s copybook of Lawrence Leadley (1827-1897), a village fiddler in

Helperby, Yorkshire. Farther north, it became popular enough to have dances

written specifically for the melody. In Scotland a country dance called Speed

the Plough (also known as the Inverness Country Dance) became popular and was

the first half of the Perth Medley, peculiar to the famous Perth Hunt Balls.

Elizabeth Burchenel printed a New England contra dance to the melody in 1918,

and Francis Linscott included a contra dance with the reel in Folk Dances of Old New England in 1939.

In fact, “Speed the Plow” became such a staple of New England dances that it

invariably turns up in almost any historical record of dance cards or fiddler’s

repertory lists in that region, and many associate it today with old New

England fiddling.

One measure of a tune’s importance to the repertoire

as a whole is how early it appears on sound recordings. “Speed the Plow” was among the first fiddle

tunes to have been heard via mechanical means. It was waxed, literally, in 1909

by the English collector Cecil Sharp, from the playing of one John Locke of

Leominster, Herefordshire, described as a “gipsy fiddler.” John Taylor recorded it commercially for the

Victor company in 1908, and Scottish melodeon player Peter Wyper included it as

part of a dance medley in a 1912 recording (Regal G6985). Although it was not

apparently absorbed into French-Canadian tradition, an early recording was made

by Qučbec fiddler Joseph Allard in 1929 (Victor 263570) under the title “Reel

du grandpčre,” a rendition later recorded by Montreal cabby and fiddler Jean

Carrignan, an admirer of Allard.

Unusual for a tune of this nature—having widespread and extremely long popularity in numerous genres—is the apparent infrequency of variants and alternate titles. There are variants of “Speed the Plow” to be sure: John Hartford likened Roy Wooliver’s “Devil’s Hornpipe” to it, and Kerry Blech identifies Kentucky fiddler Owen “Snake” Chapman’s “McMinnville’s Breakdown” as a version. Occasionally the cachet of the title caused it to become associated with other melodies. Bob Beers learned a tune by the name of “Speed the Plow” from his maternal grandfather, George Sullivan, which gained popularity after Beers played it at a Fox Hollow festival in the 1960’s. It was picked up by New Hampshire fiddler Rodney Miller and later by Seattle’s Armin Barnett, and through their playing it has gained some popularity in old-time circles, but it is melodically unrelated. The tune known as “O’Keeffe’s Speed the Plow” or “O’Keeffe’s Plow” (alternate titles include “The Kilfenora Reel,” Cronin’s Fancy Hornpipe,” “Charlie Mulvihill’s” and others) honors Sliabh Luachra fiddle great Padraig O’Keeffe, but, again, the only similarity is the title, and no melodic material is shared.

What continues to surprise is the very lack of multiplicity of titles and significant variants—often a consequence of a older tune’s drift through the ‘folk process’, for better or worse. Occasionally, as with “Speed the Plow,” especially strong melodies with equally distinctive and evocative titles survive seemingly intact. Together both are cemented in the repertoire. Remember how quickly Moorehead’s original title (“Naval Pillar”) was deposed in favor of “Speed the Plow,” obviously the better title. The tune’s strength is self-evident; it is a strong, distinctive melody, not too difficult or technically demanding, but melodically interesting. What distinction does the title hold, and why is it memorable?

It turns out that the name Speed the Plow touches an ancient archetype in British Isles folk tradition, one that would probably resonate in any agrarian setting. The phrase ‘God speed the plough’ is derived from a wish for success and prosperity in some undertaking, and is many centuries old, stemming from Medieval times. It occurs as early as the 14th century in the song sung by plough-men during the English folk-religious celebration of Plough Monday (traditionally the first Monday after the twelve days of Christmas), and is part of the ancient Plough Monday prayer—“God sped de ploue.” The day marked the beginning of the new farming season with emphasis on preparation for spring plowing. Plows themselves were sometimes blessed in the church and dragged through the streets in celebration. A Medieval artifact has survived, a little lead badge depicting a plow surmounted by a crown that was probably associated with this festival, writes Malcolm Jones in his book The Secret Middle Ages (2003). The badge was perhaps worn by teams of young men, known as ‘plough-bullocks’, ‘plough-boys’ or ‘plough-jags’, who would draw a decorated plow around the village on the designated day, asking for alms, drink or tokens, while sometimes performing a folk-play (similar to mummers or pace-egg plays). Jones finds great antiquity in the ‘God speed the plow’ notion, citing a beam in the late 14th century plough gallery of Caston Church, Norfolk, which is inscribed:

God spede the plow

And send us all corne enow

Our purpose for to mak

At crow of cok

Of the plwlete of Sygate

Be mery and glade

Wat Goodale this work mad.

Plough-Monday

celebrations were once common in much of England and survived well into the 20th

century—the custom was still extent in the 1950’s in some villages around

Nottingham, for example. However, there were times throughout the years that

residents of rural areas were not particularly pleased with an appearance of

the Plough-Bullocks, for the boundaries between playful eliciting of

contributions and the demand of them under duress were blurred. If nothing was

forthcoming retribution was often wreaked on the non-givers in the form of

plowed-up gardens, front walkways, and the like (association with the

present-day ‘trick-or-treat’ Halloween children’s rituals are apt). The habit

of collecting money to purchase the Plough-Bullocks own alcoholic drink

probably contributed as well to the degeneration of the earlier custom into

hooliganism in some areas. William Howitt (1792-1879), a Nottingham chemist and

druggist (later Alderman), wrote 1838:

Plough-Monday

celebrations were once common in much of England and survived well into the 20th

century—the custom was still extent in the 1950’s in some villages around

Nottingham, for example. However, there were times throughout the years that

residents of rural areas were not particularly pleased with an appearance of

the Plough-Bullocks, for the boundaries between playful eliciting of

contributions and the demand of them under duress were blurred. If nothing was

forthcoming retribution was often wreaked on the non-givers in the form of

plowed-up gardens, front walkways, and the like (association with the

present-day ‘trick-or-treat’ Halloween children’s rituals are apt). The habit

of collecting money to purchase the Plough-Bullocks own alcoholic drink

probably contributed as well to the degeneration of the earlier custom into

hooliganism in some areas. William Howitt (1792-1879), a Nottingham chemist and

druggist (later Alderman), wrote 1838:

"... Plough-Monday, here and there, in the thoroughly agricultural districts, [still] sends out its motley team. This consists of the farm-servants and labourers. They are dressed in harlequin guise, with wooden swords, plenty of ribbons, faces daubed with white-lead, red-ochre, and lamp-black. One is always dressed in woman's clothes and armed with a besom, a sort of burlesque mixture of Witch and Columbine. Another drives the team of men-horses with a long wand, at the end of which is tied a bladder instead of a lash; so that blows are given without pain, but plenty of noise. The insolence of these Plough-bullocks, as they are called, which might accord with ancient license, but does not at all suit modern habits, has contributed more than anything else to put them down. They visited every house of any account, and solicited a contribution in no very humble terms. If refused, it was their practice to plough up the garden walk, or do some other mischief. One band ploughed up the palisades of a widow lady of our acquaintance, and having to appear before a magistrate for it, and to pay damages, never afterwards visited that neighbourhood. In some places I have known them to enter houses, whence they could only be ejected by the main power of the collected neighbours; for they extended their excursions often to a distance of ten miles or more, and where they were most unknown they practised the greatest insolence. Nobody regrets the discontinuance of this usage."

Despite this more recent history of nuisance, the core of the Plough Monday tradition was strong enough and evocative enough that there has been a revival in several areas of Britain in recent years (often as an adjunct to the morris tradition), without the coercive behavior. It is a similar remembrance of a once-powerful agrarian symbol, the ritual blessing for good harvest, that is evoked in trace form in “Speed the Plow.”

(The author wishes to thank Lisa Ornstein for information regarding the Allard and Carignan recordings).

Andrew Kuntz

8 Veatch Street

Wappingers Falls, NY 12590

aikuntz@optonline.net

X:1

T:Speed

the Plough [1]

M:C|

L:1/8

R:Reel

S:Stewart-Robertson

– The Athole Collection (1884)

Z:AK/Fiddler’s Companion

K:A

E|A2(Ac

efec|eaec efec|dfdB cecA|FBBA GABc|ABcd efec|eaga ecAc|

decd

BcAB|FAGB A2A||g|a2 (ag aece|aAgA fAec|dfdB cecA|FBBA GABd|

cAce aece|fgaf ecAc|decd

BcAB|FAGB A2A||