3 The South Africans in East Africa

The British Chiefs of Staff in 1939

believed that if Italy joined Britain's enemies then, in East Africa, where no

military engineering organisation of any sort existed, Britain's primary object

should be to secure her lines of communication with Egypt. "For the

rest," as the British Official History remarks, "the Chiefs of Staff

were thinking entirely in terms of defence."1

In Kenya, all engineer service and

similar defence matters were still being dealt with by the A.A.Q.M.G. and

D.A.Q.M.G. or the G.S.O.(3)I. sections, and all military work was being carried

out by the Kenya and Uganda Railways, the Public Works Department, the

municipalities or the district councils. Only on 6 September 1939 was the War

Office cabled for authority to form one field company of Engineers. Three weeks

later, Lt.-Col. J. W. Lloyd Ravier became Acting C.R.E. at East Africa Force

Headquarters, and on 3 October Maj. H. H. Dugmore (killed in an air crash the

following August) became A.C.R.E. to deal with Works. He left soon afterwards

on a road reconnaissance of the almost trackless Northern Frontier District--the

"N.F.D.".

By mid-October 1939 Maj. W. I. S.

Oates--later C.R.E., 12th African Division--had been posted to

command the new field company, for which recruits were being sought from

as far afield as Dar-es-Salaam, Lusaka and Salisbury. Roads were still being

constructed by private companies, and advice on water boring was being

given by the Boring Superintendent of Southern Rhodesia. It was 8 December

before a Water Section, almost devoid of equipment, left Nairobi for

Isiolo, and they had to return within a few days to be trained. When they did

set out again a month later, they had to turn back because of the state of the

roads. Their experiences epitomised East Africa's two biggest

problems--water and roads.

It was against such a background

that Gen. Sir Archibald Wavell, as Commander-in-Chief, Middle East concluded

that if Italy did join Germany, then he would have to attack them in Abyssinia.2

He felt that French and British Somaliland provided the best bases for this

purpose, through Jibuti and Berbera, and with East Africa also placed under his

command he flew to consult Gen. Smuts on 16 March 1940. Lt.-Col. G. H. Cotton

and others had already rapidly surveyed a "Great North Road" from

Pretoria to Nairobi,3 with

--32--

Maj. F. W. Pettifer making a preliminary reconnaissance of the proposed route4

on which the exploratory convoy was commanded by Col. H. B. Klopper and

included 2/Lt. P. J. Swarts and several Sappers of 5 Field Company.5

In Kenya the C.R.E. himself was ill

and in hospital at Kabete on 20 March, but plans for the air defence of Mombasa

were produced by the beginning of May and within a few more days the laying out

of a military camp was started at Thika, just as Lt.-Col. F. E. Buller arrived

from Southern Rhodesia to take command of the Engineers as A.C.R.E.

On 8 May Lt.-Col. Buller left

Nairobi for Mombasa with a South African representative and they inspected a

camp site at Nairobi next day. By 21 May East Africa Force had been informed

that two South African Works officers could be expected shortly, and within two

days Maj. D. F. Roberts and Capt. H. C. Mullins of the S.A.E.C. were holding

discussions with the C.R.E. and A.C.R.E. concerning Works services required and

to be carried out by South Africans at Mombasa and Gilgil.

The South African officers suggested

the formation of large engineer stores and explosive dumps for materials

sent up from South Africa, and while Maj. Roberts left for Mombasa to discuss

camp sites with the Garrison Engineer there, Capt. Mullins met the C.R.E. and

A.C.R.E. and two timber mill owners in Nairobi to settle the priority of

military hutment construction. The early despatch of 16 Field Company, a

trained fighting unit, in place of a works company, had already been suggested,

and by 27 May Maj. Dugmore--the A.C.R.E., Works--and the South

Africans had selected a camp site at Gilgil.

A site at Kabete, 1,800 metres above

sea level and only 28 km outside Nairobi, was selected for a South African base

camp and depot on 28 May 1940 and approved by Col. A. J. Orenstein as Director

of Medical Services and Capt. H. C. Mullins of the S.A.E.C, Staff Captain

(Works), who was to earn the award of the M.B.E. for his remarkably courageous

services as Engineer Officer attached to Air Headquarters.

On 9 June 1940 East Africa Force

produced a tentative outline for a new Engineer organisation in East Africa

under a Chief Engineer. France had collapsed, and next day the request for a

qualified senior officer had hardly gone off to England before news was

received that Italy had entered the war on the side of Germany.

The Challenge of the N.F.D.

The day before Italy entered the

war, 16 Field Company had left Cullinan to join its advance party at Durban and

sail for Mombasa7 together with the advance party of 36 Water Supply

Company. They were hardly out of sight of land when South Africa found herself

at war with Italy, who already had some 291,000 armed men, black and white, in

Italian East Africa.8 The British forces in Kenya could muster

barely 8,500 men, there were only another 1,475 in British Somaliland, and the

Sudan boasted about 9,000.9 A Nigerian brigade

--33--

group and a Gold Coast brigade

group were on their way to Mombasa, and with the two East African brigades

already in existence they were to form the 1st and 2nd African Divisions, but

their field companies were seriously short of equipment of all kinds.

Kenya was a Crown Colony, and considered

habitable by Europeans only above 1,200 metres10. Its railways

totalled a bare 2,575 km in the country's 582,644 square kilometres of

territory. Nairobi, the capital, had the population of a town no bigger than

East London but was the hub of both road and rail communications. From here the

railway from Mombasa ran north-west to Nakuru and then ascended the great Mau

Escarpment11 before falling evenly towards Lake Victoria.

North-eastward from Nairobi ran the

line to Thika, Fort Hall, Nyeri and Nanyuki on the slopes of Mount Kenya, and

from the capital the few important roads--which were often primitive by

European standards--spread out like the branches of a tree, to the

north-west through Gilgil to Nakuru, Eldoret and Kitale on the long trek to

Lodwar and Lokitaung; through Thika northwards by way of Nanyuki, Isiolo and

Archer's Post to Laisamis and Marsabit, or eastward to Garissa on the Tana

River. Also through Isiolo, a road ran north-eastward to Habaswein and onward

to Wajir, with a roughly parallel route farther north through Archer's Post and

Melka Galla to the same destination, which was no more than a frontier fort and

customs station set up in 1928 to control the smuggling carried on over the

Italian Somaliland border.12

In peacetime the whole of the N.F.D.

was a closed area. Maps suitable for military purposes did not exist. The

tracks were hard on tyres and consisted--in the words of the seasoned

settler, Clelland Scott--of "varying densities of sand, rocks,

stones, lava belts, sand rivers and stumps". There were only two rivers,

and elsewhere one had to depend on the few widely scattered wells. To the north

and west there was fine scenery, with the dry-looking, thorny scrub cut by

rough hills and precipitous mountains. The amount of game was surprising, as

grazing seemed very sparse. But after rain this veritable desert bloomed,

with wild flowers abounding, bushes fresh with green leaves and the ground lush

with grass.13

The five routes radiating over all

this vast area from Nairobi would have to form the vital supply arteries and

main lines of communication for any force hoping to reach the borders of Abyssinia

or Italian Somaliland, and Maj.-Gen. D. P. Dickinson, commanding East

Africa Force, had an unenviable task. The frontier between Kenya and

Italian-held territory ran through uncharted bush and semi-desert for almost

all its 1,900 km from Lake Rudolf to the sea. Only along the rocky Goro

Escarpment about Moyale had there been attempts at cultivation. The 480 km belt

of the forbidding N.F.D. lay between this border and the heights of the Mau

Range, the Aberdare Mountains and Mount Kenya, with its rocky pinnacle towering

above the snow to overlook the cedar, camphor and yellowwood forests dominating

the fields of coffee, wheat and maize dotted about the predominantly

stock-raising countryside. The Equator ran a few kilometres north of the great

peak.

--34--

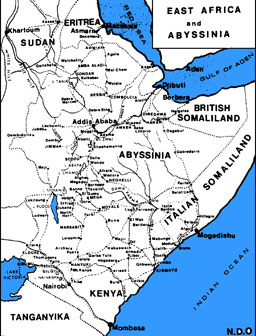

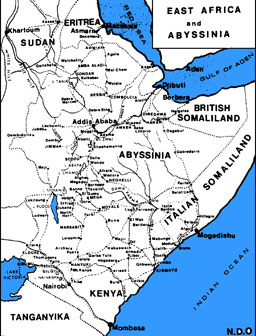

Map 2: East Africa and Abyssinia

The only points of any importance in

this enormous area of aridity beyond the Highlands were the few waterholes at

the meeting points of ancient camel caravan tracks. Such were Wajir--with

its Beau Geste fort and a few "dukas" of mud facing the Somaliland

border-- and the elevated oasis of Marsabit, almost midway between Archer's

Post and Moyale, with the Kaisut Desert to the south of it and the Chalbi and

Dida Galgalla deserts to the north-west and north-east, dissolving into

waterless plains surrounding a miserable outpost further east on a hill at

Buna.

In the south-east of the colony the

Tana River ran through Garissa and Bura on its way to the sea at Kipini in

Formosa Bay,

--35--

and offered some sort of defensive obstacle shielding the port of Mombasa as

well as the little resort of Malindi some 105 km to the north-east of it. The

river was also the home of countless mosquitoes, crocodiles and hippos,

giraffes, elephants, buffalo and all manner of antelope. Even an occasional

thirsty lion appeared at the water's edge.

Almost equidistant on the other side

of the frontier, the Juba River offered the Italians an even better defence

line well in advance of Brava and Mogadishu. Between the two rivers, as far as

was known, the country was totally waterless, and what tracks existed were

primitive in the extreme. Any attempt at capturing the Italian port of Kismayu

would require resources of motor transport and a water-carrying capacity far

beyond anything at Maj. Gen. Dickinson's disposal. He could do little more

than try to establish patrol superiority over the desolate area separating his

own scattered forces from those of the enemy,14 whose employment of

Irregular "Banda"* was matched by Somali Irregulars and later by

Abyssinian companies on the British side. The 1st African Division on the

right was stretched from Malindi to Bura on the Tana River and then along its

banks to Garissa, while 2nd African Division carried the very thinly-held line

westward from Wajir with garrisons at Marsabit and Lokitaung but virtually

nothing in between.

Enter the Sappers

No South African infantry had yet

arrived, but 16 Field Company and the advance party of 36 Water Supply

Company--the only unit of its kind in Africa15--disembarked at

Mombasa on June 16 and were met by Capt. Mullins16. The field

company left a section under 2/Lt. A. N. Gill to assist in building a field

hospital and transit camp at Mombasa, and another section under 2/Lt. A. I.

Sussman detrained at Kabete camp site, but the rest went on to Gilgil,

beautifully situated in a thriving cattle district some 2,000 metres above sea

level and about 144 km from the capital.

The Sappers immediately started

preparing camps near the railway station at Gilgil and at nearby

Langa-Langa, where Maj. Oldfield's headquarters were established. The water

supplies at Langa-Langa and the Malawa River were at once developed by 36 Water

Supply Company, which was the first unit issued with its motor vehicles and

thus became landed with all transport tasks around the camp, including the

fetching and distribution of rations.

In Nairobi on 21 June Maj. Ward

Smith of 16 Field Company reported to Lt.-Col. Buller, who was now C.R.E. Field

Units** and it was agreed that the unit would be kept on lines of

communications duties for the time being. Maj. Ward Smith was given orders to

build a pontoon bridge and throw it across the Tana River at Garissa, about 410

km east-north-east of Nairobi, on the dry-weather road towards the track to

Hagadera and the Italian

*Strictly speaking, "Bande" in the plural.

**The CRE--Commander, Royal

Engineers--was the senior Engineer officer in any British formation up to

divisional level, with a Chief Engineer at corps and army level, all under the

Engineer-in-Chief in a particular theatre of operations.

--36--

Somaliland frontier. With only a ferry operating at Garissa at the time, it was

thought that a bridge would probably be needed by 1 August, and Capt. K. T.

Gilson was put in charge of the task, and found that a 91-metre gap was to be

bridged at a point where the water was about 1,18 metres deep and running at 3

knots in country where the glare off the white sand was extremely trying to the

eyes.

Thirty pontoons were ordered locally

from the firm of Hartz and Bell, and the figure was soon increased to forty.

Meanwhile, Lt.-Col. Buller had held discussions with the A.Q.M.G. and his South

African counterpart about the availability of light railway track, and orders

were issued to press on with improving the road to Wajir with all possible

speed, using whatever equipment was available.

By 26 June a detailed survey of the

bridge site was being made by a 16 Field Company reconnaissance party who were

the first South African ground troops in the forward area. Next day Capt.

Gilson returned to Garissa with Lt. Sussman's section to prepare approaches and

get on with construction without attracting the attention of the enemy's air

reconnaissance.

It was decided to make the pontoons

only 4.57 m (15 ft) long, so that they could be transported on standard

vehicles, and then, with the C.R.E. back on duty on 4 July, the Gold Coast

Field Company promised to help with labour, and Hartz and Bell completed the

first pontoon.

Using rectangular steel tanks fitted

with artificial pointed bows, and with stout timber beams to carry the roadway

decking, Capt. Gilson completed the pontoon bridge over the Tana 42 hours ahead

of schedule. Its 20 pontoons were rafted and floated on the night of 25 July,17

and then stowed away out of sight against the bank before daylight. The success

of the operation caused 1st African Division to cast covetous eyes on the South

African Engineer unit, as they had no divisional field company of their own.

Engineer Organisation Sorted Out

The advance party of the S.A. Survey

Company had now also reached Nairobi under Capt. C. C. Allen, and with more

South African Sapper units expected, it was becoming a matter of some urgency

to organise their command and administration on a proper basis. Thus, when the

Engineer-in-Chief, Middle East (Maj.-Gen. H. B. W. Hughes) arrived at Kisumu by

air from Cairo on 8 July, it was provisionally agreed that the Engineer

organisation in East Africa would include a C.R.E. Corps Troops (controlling

Pioneer and Works companies), a C.R.E. Works Services North (for the Nairobi

and Nanyuki areas), a C.R.E. Works Services South (Mombasa and

Tanganyika), a C.R.E. Uganda (including the Soroti and Juba routes--not to

be confused with the Juba River), a C.R.E. Lines of Communication (for roads,

water and transportation units), and C.R.E's for each of the three divisions in

the field.

The whole organisation was to be

under a Chief Engineer, with a deputy and staff, and it was agreed that field

park companies would be added to divisional establishments.

--37--

By the time the Engineer-in-Chief

took off again on his return to Cairo on 10 July, eight works officers had

arrived from South Africa to assist at Gilgil, Mombasa, Nairobi and Nyeri and

in works services generally. More road equipment was still urgently needed in

the N.F.D., and after conferring most secretly with the Commander-in-Chief,

Middle East and the D.A.Q.M.G. on 13 July about future operations, the C.R.E.

met Lt.-Col. Shannon to discuss road construction. It was decided that

Lt.-Col. Shannon and Capt. East King should inspect the Shafa Dinka and Wajir

roads to determine which could best be developed by South African road

construction companies.

After driving a small British force

out of British Moyale in the north of Kenya on 14 July 1940 the Italians

displayed no further initiative.

Construction of the base camps at

Gilgil and Langa-Langa went ahead, with both the field company sections and the

Water Supply Company in what was theoretically a works company role. The 16

Field Company's section at Langa-Langa, working from 6.15 a.m. to 6 p.m. every

day, was having difficulty owing to the shortage of gum poles, scantlings, pipe

fittings and other materials, but 36 Water Supply Company was able to complete

the water installation to accommodate 1st S.A. Infantry Brigade, who reached

Gilgil on 25 July and were joined there four days later by 1 Field Company, who

had sailed with the main body of the Water Supply Company, 35 Works Company, 37

Forestry Company and 28 Road Construction Company and landed at Mombasa on 28 July.

At Gilgil sufficient cover plus

kitchens, ablutions and water, was available, but many tents were still being

used,18 and 1 Field Company was soon assisting with camp

construction, which was taken over by Maj. A. D. Hughes and 35 Works Company,

who also began building a bridge on the road to Thomson's Falls. A section

under Lt. D. C. Midgley moved up to Wajir to help build defences.19

Meanwhile, 16 Field Company continued its work at Langa-Langa and on a new

hospital.

The foundations of a proper Engineer

organisation for East Africa Force were at last being laid, and on 26 July an

aircraft had landed at Nairobi from Pretoria, carrying Col. A. Minnis, who had

been sent out from England as Chief Engineer and was accompanied by Maj. H. H.

C. Sugden as G.S.O.(2) and Capt. J. H. Amers. Within a few days--though a

final Engineer organisation was not yet established--long discussions were

being held with the D.A.Q.M.G. and the Chief Engineer of the Kenya and Uganda

Railways regarding ambitious plans for a projected new railway line to

improve communications. More work in yet another field lay ahead of the

S.A.E.C.

It was not until the arrival of a

number of Royal Engineer officers and the other ranks of the new Chief

Engineer's staff on 18 August-- the day before the Italians entered

Berbera in British Somaliland-- that the Engineer organisation could take

final shape, but already work could be arranged to fit in with the new

dispensation. This left Maj. Sugden as G.S.O.(2) to Col. Minnis, with two Staff

Officers--

--38--

Maj. D. F. Roberts for the S.A.E.C. and another for East African

Engineers--as well as an Intelligence Officer (Capt. J. T. S. Tut-ton), a

Camouflage Officer (Capt. A. M. Ayrton) and a Surveyor of Works (Lt. H. A.

Ackland). Apart from the Sapper units allocated to the three field divisions,

this headquarters was to control a growing number of units through a D.C.E.

Works and a D.C.E. Lines of Communications.

Still more Building

At Gilgil, where the soil was

impervious, difficulty arose owing to the impossibility of disposing of waste

water by means of the usual French drain or soakaway, but Maj. Hughes of 35

Works Company overcame this problem by having 36 Water Supply Company drill

boreholes down into the underlying porous lava formation, to which waste water

was then led via a greasetrap. The local lava could be cut to shape even with a

handsaw and came in most useful for constructing the ovens for a large field

bakery at the camp, where Lt. T. C. Menne kept 35 Works Company well provided

with venison as well as pheasant and trout for the officers' mess, as the

country round about boasted streams well stocked with fish and teemed with

game.

Though they had handed over their

construction work in this idyllic-sounding setting, 16 Field Company was not

free of building commitments, and on 3 August they sent off Lt. A. N. Gill and

fourteen men to Malindi on the coast road north of Mombasa to build a camp

there for an early warning radar station manned by Special Signals Service men

and for the King's African Rifles. No. 2 Section was still at Garissa with 1st

African Division and No. 3 was fully occupied on work at the hospital in

Mombasa--where they had ten of their own men down with malaria by 6

September--and on fortifications and camouflage at Port Reitz aerodrome

about 12 km from Kilindini harbour.

What might be termed the field

company's first "contact" with the enemy came when Lt. Sussman of the

section at Garissa reported that he and Lt. Mount Stevens of 3 Field Company,

Royal West African Frontier Force, had located 12 unexploded bombs 5.6 km north

of the road junction at Dololo. Having found out how these "duds" were fused by blowing them open with a light charge of gelignite, he then

submitted working drawings to 16 Field Company headquarters and disposed of

eight bombs on 24 August and the rest next day.

Maj. N. G. Huntly was already in

Nairobi as Assistant Director of Survey when the main body of Maj. Short's S.A.

Survey Company arrived at Langata Camp overland from Broken Hill on 3 August

and settled down to training before moving to permanent quarters. They had a

Trigonometrical Group of five sections, a Geodetic Section and an Instrument

Repair Section as well as a Map Production Section and a Mapping

(Photo-Topo) Group, but the latter had been temporarily left behind at Premier

Mine. Two sections of the Photo-Topo Group, whose personnel were trained and

equipped to

--39--

produce maps either from air photos or by ground methods, joined the Company at

Nairobi in December. The Lithographic Section of Mobile Map Printing and

Printing Company was attached to the Survey Company at about the same time.

Water, Water--Nowhere

As one Sapper unit from South Africa

followed another to Kenya, so their specialised functions became more clearly

separated, but as long as East Africa Force was still preparing to take the

offensive, their duties continued to overlap. Nevertheless, the need for proper

water supplies and good roads remained of the greatest importance and, if the

roads of Kenya were atrocious from a military point of view, the water

situation was even worse in the arid wastes separating the colony from

enemy territory. The field sections of the Survey Company, already in the

N.F.D., found the lack of water in the remote areas especially trying, and pack

donkeys were their only suitable means of transport in some parts: The civilian

drilling company which had previously been employed without much success

was withdrawn on arrival of 36 Water Supply Company, and the South Africans

rapidly deployed their eight drilling machines to cover the four important

routes: Kitale-Lodwar-Lokitaung; to Marsabit including the Kaisut and

Chalbi deserts; Wajir-Buna; and the road to Garissa.20

A boring plant was soon on its way

to Habaswein, and on 5 August--the day the Italians entered British

Somaliland--Maj. Oldfield and Lt. A. G. Richardson arrived at Nanyuki,

followed by a detachment of 19 men who left for the N.F.D. under Richardson two

days later. Part of the unit was still installing a pump, pipeline and reservoir

scheme on the Malawa River and storage tanks at Gilgil, but the first borehole

was actually drilled at Buna, the small outpost between Moyale and Wajir. Enemy

Capronis took to bombing the rigs, and the boring machine was pulled back from

the area.

The company soon realised that the

Italians were locating the boring machines, which would naturally make tempting

targets, by spotting the characteristic shadow of the mast. Trenches were dug,

radiating from the machine, and the sun--no matter where it was--threw

a pattern of shadows which brought an end to the trouble. The King's African

Rifles detachment at the Buna outpost had to pull back in face of superior

enemy forces, unfortunately, and the boreholes, which were already delivering a

promising supply of water, had to be destroyed to prevent the enemy's

benefiting from all the hard work that had gone into drilling them.

A Bombshell

As a result of 36 Water Supply

Company's operations in the Turkana, the S.A.E.C. had its first offensive, and

most irregular, brush with the enemy. When Capt. J. de Wet of the S.A.A.F.

crashed at Lokitaung after his Fairey Battle had been badly damaged during

a raid on Jimma, Lt. Oliver Carey was ordered to fly

--40--

mechanics up from Nairobi in an old Vickers Valentia on 14 August. He landed

among thorn trees near a 36 Water Supply company boring machine and was greeted

by Lt. J. G. Lentzner, who soon heard how bored Carey was with transport flying

and no action. Possibly feeling the same way, Lentzner decided to remedy the

situation by packing a 44-gallon drum with sewing-machine parts, nuts and bolts

and other spares found in an abandoned Indian shop. In the middle of this

conglomeration of metal he put a good charge of gelignite.

Fitted with a 60-second delay fuse,

the home-made bomb was ready for use, and at 4 a.m. the transport pilot was

called to inspect this masterpiece of the South African armaments industry.

With fighter pilot Lt. Oscar Coetzee, A./Sgt. F. Squares, A./Sgt. Ted Armour

and Lt. Joe Lentzner as crew, Carey took off as soon as the door of his

Valentia had been removed and the 44-gallon drum loaded aboard. He headed

eastwards over Lake Rudolf in the darkness and then swung to the north.

As day broke, the pilot told his

"bomb-aimer", Lentzner, to stand by. Then he swooped low, straight

for the Italian fort at Nama-ruputh till the aircraft was actually below the

top of the walls, with the Italian machine-guns firing down on it. Lt. Coetzee

was hit in the foot and the pilot was lightly wounded on the forehead before he

pulled the ungainly Valentia up over a courtyard full of wakening soldiers,

into the midst of whom Lentzner launched his extraordinary bomb by shoving

it out of the doorway with fuse alight.

For some moments nothing happened.

Then, as curious Italians began to recover from their surprise, the drum

exploded with an almightly flash and killed a number of the hapless men. The

whole incident was covered up with the connivance of an Indian medical officer

attached to the Nigerians, and with air mechanics sworn to secrecy. When

Intelligence picked up a Radio Roma report of an R.A.F. bombing attack on

Namaruputh, unfortunately, the secret leaked out.

Within a month the pilot was

transferred* to a more active squadron, but Lentzner remained with 36 Water

Supply Company and on 19 August he returned to unit headquarters. Two days

later Capt. F. C. Ellison and 24 other ranks were on their way to Lodwar in

convoy, and Sgt. J. P. de Jager with another detachment was on the train to

Kitale, en route for Kalin.

Maj. Oldfield, found that visiting

his widely separated detachments was a strenuous task. To be completely

self-contained, he used a 1-tonner to carry rations and a 3-ton truck for fuel,

and armed himself with a double-barrelled shotgun. His one driver was an

excellent cook, and could roast birds to a turn in a 4-gallon petrol tin oven.

Exchanging their issue M & V rations for green peas when they contacted

isolated units, they thus eked out their rations with fresh meat in spite of

being on the move and many kilometres from

*There remains some confusion over

the composition of the crew, who are shown, in a photograph in A Gathering of

Eagles, the history of the SAAF, as Lt. J. Lentzner, Sergeant F. Squares, Lt.

C. S. Kearey (sic), Spr. du Toit and Sgt. E. Armour. However, in the pilot's

own version on page 81 of the same volume, Lt. Oscar Coetzee is mentioned,

without Spr. du Toit.

--41--

civilisation. The unit commander's vehicles covered some 80,000 km during the

campaign.

Lt. J. G. Lentzner, detailed to

supply the infantry with water, had set out on his return to Lodwar on August

24, before the Dukes and 1 Field Company left Gilgil for the Turkana. There

water supply and road maintenance became the main concern of the Sapper field

section under Lt. D. A. Anderson, as the Turkwel River at Lodwar soon ran dry.

Forward posts at Lokitaung and Kalin were some 144 km north of the Dukes'

battalion headquarters at Lodwar, and at Kalin itself a series of waterholes

offered the only dependable supply for many kilometres unless 36 Water Supply

Company's small detachment could discover more in an area where the average

daily temperature could reach over 100° Fahrenheit. The field company section

had to send a detachment back to the Nepau Pass to help 36 Water Supply

Company's handful of men with well sinking.

The 1 Field Company section remained

in the Turkana until shortly before the Dukes were relieved on 7 October,21

the day after 3 Field Company--having arrived overland at Nairobi on 2

October-- was ordered to Gilgil from Nanyuki.22

The Water Supply Company, however,

continued operating in the Turkana, where Lt. Lentzner was responsible for some

very fine work, not only in connection with his normal duties but also (as the

only Engineer officer at various times) for demolition work after air attacks.

The success of water supplies in this extremely arid area was largely due to

his untiring efforts with only a handful of men and under most trying

conditions. Cpl. A. S. van Wyk proved himself a particularly capable and

industrious leading driller and N.C.O. He had also been with the rig evacuated

from Buna under enemy pressure, and did such magnificent work in that area and

in the Turkana that he was awarded the B.E.M.

It was not long before Maj.

Oldfield's Water Supply Company found itself facing an unexpected difficulty.

At each watering point which his specialists established, he found that he had

to leave a couple of Sappers to operate the equipment they had installed. With

road construction companies, whole brigade groups of infantry and other arms

all requiring water, the drain on a single unit's manpower was absolutely

disproportionate, and after many complaints and requests a Water Maintenance

Unit was formed to solve the problem.

Boring machines were widely

scattered in a continuous search for water, and the unit was already pumping

water at the Malawa River pumphouse and at brigade headquarters, and covering

the pipeline from the pumphouse to the main reservoir while awaiting the

arrival of the rest of its personnel. Before the end of October a detachment

was building a settling tank and reservoir 19 km out of Nairobi at Ruiru, and

from there they would lay pipes to the Mitubiri camp just north of Thika and

install a 6,5 h.p. Ruston engine.

A detachment under Lt. A. C. Stimson

left Gilgil on 2 September for Nyeri, to provide water for the hospital, which

was a big task involving even plumbing to all blocks. Some three weeks later

Lt.

--42--

Lentzner's detachment at Lodwar left for Kalin but was first diverted to

sink a well at Lokitaung.

Since the Dukes had decided not to

defend the existing perimeter, Plant No. 41 at Kalin had had to be moved to

drill at a new site, where work was in progress when Capt. F. C. Ellison was

informed that an enemy raiding party was approaching. Machine-gun fire was

heard and a guard put on the machine, but fortunately nothing untoward

happened. The test pump had to be used for the rest of the month to provide

troops in the area with water.

Work at Ruiru continued throughout

September, and another detachment was kept busy on wells at Nguni and at

Tomboni. Drilling at the 5-Mile post on the Isiolo-Garba Tula road was several

times interrupted by enemy aircraft, and at Lak Boggal, midway between

Habaswein and Wajir, boreholes were unsuccessful. North of Ndege's Nest

efforts were equally disappointing and some holes at Habaswein had also to be

abandoned, largely owing to clogging by sand. Maj. Oldfield's own headquarters

at Langa did numerous jobs in the area.

The vital search for water was being

pursued in earnest, and on 3 October 3 the 42 Geological Survey Section under

Maj. H. F. Frommurze reached Mombasa. They soon had reconnaissance parties

out to select possible water-boring sites, and the unit headquarters moved

into Langa camp. One detachment worked its way eastward through Garissa, a

second conducted its search for water north of Kitale, and a third operated

between these two in the region stretching from Marsabit right up to Mega.

Using magnetometers and electrical resistivity apparatus of more than one type,

highly professional Sappers gathered information on subterranean geological

structures which gave them an indication of where water might be found. They

were thus of immense help to the water-boring parties, and actually located

40,7 per cent of the holes which successfully yielded potable water. Numerous

other sites were indicated, where water was also found, but regrettably it

turned out to be brackish.23

On every main route in Kenya,

detachments from 36 Water Supply Company could be found, and hopes alternately

soared and sank as boreholes gave unpredictably good or poor results. No

serious attempt could be made even to close up to the frontiers without

adequate water not only for the troops themselves but also for the growing mass

of vehicles and machines which any reasonably equipped modern force required.

The local well at Lokitaung had

dried up, but Sgt. J. P. de Jager's crew found some water at about 20 metres,

to the great relief of the men guarding the main approach from Abyssinia.

Another company of infantry was at Kalin, a few kilometres farther west, where

the waterholes still provided the only dependable supply for many kilometres.

Two enemy aircraft flew over the

South African drilling site near Lake Rudolf on 20 October, and on the 24th one

team found 1,100 litres an hour and began erecting a 4,500 litre tank to supply

a company of 25th E.A. Brigade, whose headquarters were now at Lokitaung. On

instructions from Force Headquarters, Maj. Oldfield,

--43--

Capt. G. L. Paver of the Geological Survey Section, and Capt. F. C. Ellison

even carried out a survey of the Soroti-Juba route, with a view to increasing

the water sources for convoys carrying supplies overland to the Middle East.

At Nyeri, the Water Supply Company

did much work on the hospitals during November, but there was no slackening in

the widespread search for water everywhere. Detachments were constantly on

the move, with No. 9 alone working at Habaswein, Isiolo, Laisamis, Marsabit and

then at Garba Tula during November! Boreholes were drilled on the Thika-Garissa

road, at Laisamis and at Marsabit, at Lak Boggal, Habaswein, Muddo Gashi and

elsewhere. Apart from the inevitable disappointment felt when a hole did

not yield any water, the only incident which marred the company's month

was the death of Spr. G. P. Cocklin on 8 November as the result of a

motor-cycle accident.

Build-up of the Forces

With the training of an effective

force in Kenya a matter of urgency, every type of Engineer company was

inspanned to do a variety of jobs, regardless of its conventional role, and

there was an unending demand for materials, firstly for the construction of

camps to receive the increasing flow of troops and, once road-building began,

for the construction or improvement of bridges. The call for timber grew more

clamorous by the day, and when 37 Forestry Company on 29 July 1940 marched into

Camp No. 3 at Gilgil they barely had time to settle in before they were fully

occupied constructing buildings and adapting to a works company role. This

kept them busy until 5 August, when the unit commander, Capt. F. S. Laughton

and 2/Lt. D. J. Strauss visited Nairobi to see Col. Craig. Joined by Capt. H.

R. Roberts of 35 Works Company, they left on 9 August for a reconnaissance into

Tanganyika to an area close to the railway line linking Tanga with the

Mombasa-Nairobi line by way of Taveta, which had been a keypoint in Gen.

Smuts's campaign in German East Africa in 1916.24 They were

particularly interested in the Shume sawmill in the Usambara Mountains forest,

and returned on 22 August.

Parties of men from the Forestry

Company were being taken out not only to Naivasha on the lake north-west of

Nairobi, but also to the forests north of Gilgil, where they worked during the

last few days of August and throughout September, felling and delivering sisal

poles and papyrus as well as bamboo for construction of Camp No. 13 for the infantry.

Base works continued, but preparations for active operations were only in their

infancy.

Maj. Ward Smith's headquarters and

No. 1 Section of 16 Field Company pulled out from Gilgil on 2 September, picked

up No. 3 Section in Nairobi and took the road northward through Thika, to camp

at Mitubiri and report to the C.R.E., 1st African Division, in which they

became divisional troops, though normally a division's field companies were

attached to its constituent brigades. When Maj.-Gen. H. E. de R. Wetherall,

commanding the division, visited

--44--

What it was really like. Dominion troops, during a lull in the righting in France

during World War I,

rest or write home from the shelter of a trench.

What it might have been. A section of a World War I pattern trench

constructed by 5

Field Company at Auckland Park, Johannesburg early in 1940

The military hospital at Nyeri, where 36 Water Supply Company as early as the first

week of September 1940<

began establishing the water supply and 33 Works Company

completed construction of essential services later.

No fewer than seven South African roads companies served in East Africa, and some of

their Sappers are here seen<

constructing one of the many culverts they had to

build in establishing reasonable lines of communication in Kenya.

the company on 5 September, the main topic of discussion was inevitably the

problem of water, but on 11 September Maj. Ward Smith's headquarters, and No.'s

1 and 3 Sections moved to Mwingi, the former going on next day to Garissa to

relieve No. 2 Section. There they soon began preparing an anti-tank minefield

and fortifying the forward defended localities, before Capt. K. T. Gilson

left on 24 September for a promotion course in South Africa.

By the end of the month Lt. B. P.

Stewart had had 4,000 holes dug forward of the Dannert wire at Garissa, and 1

180 mines had already been laid to discourage an advance by any enemy who might

incredibly manage to cross the 150 km or so of barren scrub between the Tana

River and the Italian border at this point. The mines, made up in

Nairobi--since none were available for issue locally-- were primitive

but effective, and were assembled and armed in the bush.

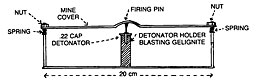

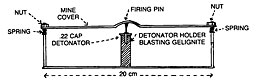

An improvised mine made in Nairobi

This improvised mine was quite

effective, but the company's "bag" comprised only one elephant and a

giraffe, and the Sappers had eventually to lift their own minefield.

Game was plentiful in the Tana River

area, where 16 Field Company was bombed several times by Capronis. Local Somalis

were then encouraged to guide the Sappers to any unexploded bombs so that the

mechanisms could be examined and reported on, but on one occasion a Native

threw a stone into a cluster of palms and annoyed two hitherto hidden

elephants. The huge beasts stormed the Sapper party, who turned and ran. When

they did eventually return, the elephants had vanished into the forest but Spr.

Hoffman was impaled on thorns in thick bush and had to be painfully extricated

before the searchers could continue their exploration, which uncovered

some interesting "duds".

Headquarters and No. 1 Section of 1

Field Company left Gilgil for Wajir on 18 September to construct defensive

works, and for the night of 20-21 September they halted some 16 km beyond Habaswein

and posted sentries to look out for enemy raiding parties. A guard, alerted by

the sound of someone moving and suspecting hostile Banda, opened fire and was

soon horrified to discover that he had killed Spr. R. A. H. Simpson and

seriously wounded Spr. G. D. Jackson, who was rushed back to 4 Gold Coast Field

Ambulance at Habaswein but died early the following morning.25

Sadly the company went on to assist

in the construction of the Wajir defences, which would keep them occupied for

almost five

--45--

weeks, with 55 men from 35 Works Company also hard at work within a few days.

At a conference at the Gold Coast Engineer headquarters, it was decided that 35

Works Company would build pillboxes while 1 Field Company attended to the

construction of tank traps, and in fact the works company not only attended to

the main fortifications but later also built a bombproof hospital and command

headquarters. Italian aircraft dropped incendiaries and high explosive

anti-personnel bombs, which left the Sappers the additional dangerous task of

disposing of the unexploded bombs,26 and Lt. Midgley also found that

the original design for the pillboxes was not really satisfactory. Adjustments

had to be made, especially for the use of Bren guns.

There had been but one permanent

airfield in Kenya at the outbreak of war, and it could accommodate only a

single squadron.27 With Capt. Mullins directing work on airstrips

and landing grounds,28 some facilities had already been improvised,

but on 8 October Lt. Sussman's section of 16 Field Company was given the

immense task of clearing another landing ground at Chesmarapa, some 60 km

north-west of Garissa and close to the Tana River. No less than 564,367 m2

of bush had to be pulled out without bulldozers, but Sussman and his Sappers

set off on 10 October and used their own 3-tonners instead, by removing the

tailboards and lashing tree trunks about 2,7 metres long and 0,27 metres in

diameter across the back of the lorries. Reversing at full speed, the driver

declutched to save the transmission just before hitting a tree, which then

broke or was uprooted if the effort was successful. Though this method worked,

it hardly ensured a long life for the 3-tonners, but once the bush was cleared

a road grader was to be provided to level the runways. It was arranged that a

3-tonner fitted with a treble-sheave 3-inch tackle would cope with the larger

trees.

Training Depot

The Engineer Training and Base

Depot, with 1,020 all ranks under Maj. C. B. Stewart reached Gilgil on 5

October and considerably increased the South African Sapper strength in

East Africa, where it soon became the S.A.E.C. Training Section of No. 1 Base

Reinforcement and Training Depot, S.A. Forces. Meanwhile, haying arrived at

Nairobi on 2 October and being placed under 2nd African Division, the 3 Field

Company now had Lt. J. C. Smuts's section at Habaswein and Lt. E. Morley's at

Garba Tula, though the rest of the unit remained at Nanyuki for a fortnight.

Then company headquarters moved up to Wajir to assist with the tank trap,

which was being hewn out of almost solid rock with the aid of blasting. Nearby

wells were also cleaned out and developed29 and a 36 Water Supply

Company boring machine moved up from Lak Boggal.

Demands for S.A.E.C. services had

thus already spread beyond the requirements of the Mobile Field Force itself,

and on 20 October Maj.-Gen. Brink visited Col. Minnis in hospital and agreed to

the provision of a South African field company and a field park company for

each of the two African divisions, in addition to the full S.A.E.C.

--46--

complement for the Mobile Field Force. Both 3 and 16 Field Companies were

involved, together with 17 and 19 Div. Field Park Companies. Further

requirements for Corps Troops and the lines of communication would be discussed

when the Chief Engineer visited South Africa, which he was not able to do for

some weeks.

By 21 October 3 Field Company had

taken over from the 1 Field Company detachment at Wajir, and the latter were on

their way to join their other sections at Habaswein. At Wajir itself, after

seeing the difficulties of excavating a tanktrap in limestone, 35 Works Company

experimented with "non-setting" mud made by mixing local soil with

sodium carbonate in a suitable pit. A S.A. Tank Corps crew eventually got a

light tank out of this mess, but were very unhappy about having to clean the

mud out of the tank tracks.

Maj. D. H. Levinkind's 33 Works

Company disembarked at Mombasa and entrained for Gilgil the day 3 Field Company

took over at Wajir, and they soon started work on drainage for No. 3 Casualty

Clearing Station and on additional camp buildings, water supplies and

reservoirs to provide for the increasing number of units reaching the theatre.

To the east, 16 Field Company now

remained with 1st African Division, and on 18 October they sent Sgt. H. A.

Wright and 20 men southward to build two bridges over the Lak Tula, a

watercourse running into the Tana about midway between Garissa and Bura. The

unit transport involved in tree-pulling at Chesmarapa landing ground continued

to take a hammering and the Sappers there, almost on the Equator, had no

protective troops as a safeguard against cut-throat "Banda" patrols.

Two sections were still on defensive works near Garissa, when three Caproni

bombers on 19 October made an unsuccessful attack on the new pontoon bridge

over the Tana River.

The heat was so oppressive in the

area that daytime work was impossible after 12.30 p.m., and the older men were

particularly affected. By 24 October no fewer than 31 members of the field

company--with some 250 effectives under normal circumstances-- were

in hospital. The end of the month found heat exhaustion taking serious toll.

Then the rains began, causing floods which delayed completion of the second

bridge over the Lak Tula by washing away the foundations.

Though 16 Field Company headquarters

remained at Garissa, the unit had also to operate the 1st African Division

field park dump 192 km back at Mwingi on the road to the Tana from Thika.

Matters of Policy

There was still no agreement in the

highest quarters as regards any aggressive action in East Africa. Maj.-Gen.

Brink, flying from South Africa on 20 October, discussed future operations in

Kenya under Lt.-Gen. Dickinson, but even after a quick visit to 1st S.A.

Infantry Brigade at Habaswein, he was left with only a very vague idea of

operational plans. Meanwhile, the 2nd S.A. Infantry Brigade

--47--

under Brig. F. L. A. Buchanan had arrived at Mombasa on 21 October and

entrained immediately for Gilgil.30

To avoid future confusion, East

Africa Force renumbered the two divisions already in Kenya, making them 11th

and 12th African Divisions, and on 28 October Gen. Wavell landed at Khartoum in

the Sudan with Mr. Anthony Eden for discussions on the situation in East

Africa. Gen. Smuts, Lt.-Gen. Sir Pierre van Ryneveld and Lt.-Gen. Dickinson

were already there, together with Lt.-Gen. Alan Cunningham, who had been

selected by Wavell to replace Dickinson, whose health was failing.

Knocking out the Italians in East Africa, Gen. Smuts stressed, would release

significant forces for use elsewhere.

The period of the "short

rains", from October to December, was already upon them in Kenya,

seriously affecting mobility on the inadequate roads and tracks. And the

"long rains" could be expected during March-May. Reasonably dry

weather might be enjoyed in the coastal areas from December to March, and

again later, from some time in May until October, and this had a vital bearing

on any planning of operations against Italian Somaliland from Kenya.

On 29 October Gen. Smuts arrived

back at Nairobi, with the new G.O.C., East Africa Force, Lt.-Gen. Cunningham.

Visiting South African troops, the South African C-in-C had a few brief moments

with his son at Wajir, and gained fresh personal knowledge of local conditions

from the many officers to whom he spoke. It was left to Gen. Cunningham to

examine the possibility of capturing Kismayu at the same time as forces from

the Sudan moved against Kassala in January 1941,32 just after the

"short rains".

The new G.O.C., East Africa Force

took only a fortnight to advise postponement of any action against Kismayu

until after the Spring rains, which meant that the attack could not be made

before May 1941. Of particular significance to the Sappers was his anticipation

of great difficulty in moving and supplying his troops across the wide stretches

of desert before the frontier of Italian Somaliland.

Gen. Wavell wished to carry out only

minor operations on the northern front of Kenya during December, and Mr.

Churchill was shocked. Even the Chief of the Imperial General Staff hoped the

attack on Kismayu in the south need not be postponed,34 and the

capture of this port as another sea base remained a priority task for East

Africa Force.35

No matter what plans might be

hatched in Cairo, London or Pretoria, however, no large-scale operations were

possible from Kenya without better roads and the availability of water. East

Africa Force headquarters was well aware of the fact. With a pre-war Minister

of Defence convinced that South Africa would not have to make her maximum

effort until six months after the outbreak of hostilities, and under a

government committed right up until the outbreak of World War II to a policy of

non-belligerence, the build-up of the U.D.F. could only have been directed in

peacetime towards what its name implied--namely defence. Even after Italy

joined Germany against the Allies, neither side could seriously have

--48--

contemplated major operations across the forbidding desert separating

Kenya from Abyssinia or Italian Somaliland, and no one responsible for the

higher direction of operations from London could have realised the potential of

South Africa's engineering resources, especially in the direction of road

building and water boring. Yet within South Africa itself there existed a

capacity ideally suited for making the crossing of the desert possible.

Nowhere else in the Commonwealth at

that time were there any units like the South African road-construction organisations

and the Irrigation Department, who could mobilise whole companies which could

move quickly to Kenya, together with their superb plant, skill and experience.

Initial forays into the N.F.D. could

be little more than experimental, but once its possibilities had been

realised by the S.A.E.C, the invasion of Italian East African territory became

a feasible proposition with significant consequences for the Middle East. Once

started, an offensive could nevertheless become bogged down, but the very nature

of engineering in South Africa at that time ensured a supply of resourceful men

used to thinking for themselves and to overcoming difficulties even in

enterprises on the largest scale. The future was to show that military success

throughout East Africa and Abyssinia would have been almost impossible without

the S.A.E.C.

--49--

Contents

Previous Chapter [2] **

Next Chapter [4]

ANNOTATIONS

1.

History of the Second World War--Grand Strategy, Vol. I,

pp. 664-665.

2.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 5.

3.

Nine Flames, p. 12.

4.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

pp. 5, 6.

5.

SA. Sapper, February 1967.

6.

Eastern Africa Today, p. 235.

[No footnote marker in text.]

7.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 29.

8.

La Guerra in Africa Orientate, Allegato I.

9.

The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol. I,

p. 94.

10.

The South and East African Year Book and Guide, pp. 782, 797-799, 806.

11.

Eastern Africa Today.

12.

The South and East African Year Book and Guide, p. 960.

13.

Abyssinian Patchwork, pp. 58, 59.

14.

Wavell's Despatch, Supplement to the London Gazette No. 37645, (H.M.S.O.) London, 10 July 1946.

p. 3558.

15.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 29.

16.

Nine Flames, p. 13.

17.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 29.

18.

The Dukes, p. 78.

19.

SA. Sapper, February 1955.

20.

Nine Flames, p. 17.

21.

The Dukes, pp. 79, 82.

22.

Militaria 6/1, 1976. p. 4.

23.

SA. Sapper, May 1955.

24.

The South Africans with Gen. Smuts in German East Africa, p. 71.

25.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 37.

26.

ibid, p. 38.

27.

The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol. I,

p. 69.

28.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 38.

29.

Militaria 6/1, 1976. p. 4.

30.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 57.

31.

ibid. p. 58.

[No footnote marker in text.]

32.

The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol. I.

p. 392.

33.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 62.

[No footnote marker in text.]

34.

The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol. I.

p. 393.

35.

East African and Abyssinian Campaigns,

p. 69.