CHAPTER V

Up From Papua

Concept of Strategy

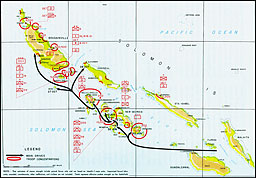

The successful culmination of the Papuan Campaign opened the way for a drive up the New Guinea coast and laid the groundwork for long-range offensive planning which would disrupt Japanese strategy and destroy their war machine in the Southwest Pacific. The bitterness of the struggle in Papua, however, indicated the formidable task that lay ahead. The Japanese still occupied most of New Guinea, maintaining strong bases at Salamaua and Lae. On New Britain, Rabaul remained the focal point for the protection and reinforcement of their holdings in New Ireland, the northern Solomons, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the whole northeast area. Allied victories in Papua and Guadalcanal had temporarily contained the Japanese but did not threaten their main centers of power. These victories, however, provided invaluable bases for further assault and made possible a broader concept of strategy and offensive operations. (Plate No. 30)

To push back the Japanese perimeter of conquest by direct pressure against the mass of enemy occupied islands would be a long and costly effort. General MacArthur lacked the forces necessary to carry out such a scheme of frontal attack even if he was so minded for the Papuan Campaign had exhausted many of his troops and much equipment. Replacements trickled in slowly, providing only the minimum essentials with which to conduct immediate operations.

General MacArthur, however, envisioned a strategy of an entirely different nature:

My strategic conception for the Pacific Theater, which I outlined after the Papuan Campaign and have since consistently advocated, contemplates massive strokes against only main strategic objectives, utilizing surprise and air-ground striking power supported and assisted by the fleet. This is the very opposite of what is termed 'island hopping' which is the gradual pushing back of the enemy by direct frontal pressure with the consequent heavy casualties which will certainly be involved. Key points must of course be taken but a wise choice of such will obviate the need for storming the mass of islands now in enemy possession. 'Island hopping' with extravagant losses and slow progress...is not my idea of how to end the war as soon and as cheaply as possible. New conditions require for solution and new weapons require for maximum application new and imaginative methods. Wars are never won in the past.1

The successful employment of this type of strategy called for the wise selection of key points as objectives and the careful choosing of the most opportune moment to strike. General MacArthur accordingly applied his major efforts to the seizure of areas which were suitable for airfield and base development but which were only lightly defended by the enemy. In this way he could move his bomber line forward and yet avoid the bloody losses and drain on his resources which would result from frontal assaults on positions where the Japanese were

--100--

concentrated in force. Thus, by daring forward strikes, by neutralizing and by-passing enemy centers of strength, and by judicious use of his air forces to cover each movement, General MacArthur intended to destroy Japanese power in New Guinea and adjacent islands and clear the way for a drive to the Philippines.2

The Struggle for Wau

When the ultimate fall of Guadalcanal and Papua became a certainty, the Japanese decided to consolidate their positions in the Southwest Pacific Area and retract their first line of defense. The key points along this new defensive perimeter included northern New Guinea, New Britain, and the northern Solomons. New Guinea in particular assumed special significance. Not only was it a strategic point on the right flank of the new defense line but its loss would provide the Allies with an ideal springboard for a thrust into the heart of the Japanese inner zones of operations.3

Accordingly, at the end of 1942, the Commander of the Japanese Eighteenth Army began to occupy and fortify points along the northern coast of New Guinea, landing fresh forces at Wewak and Madang. Airfields on Lae and Salamaua on the east coast were further developed and put to use. Plans were also made to send the entire Japanese 51st Division to secure and hold established positions in New Guinea and at the same time to exploit all possibilities for offensive action.4

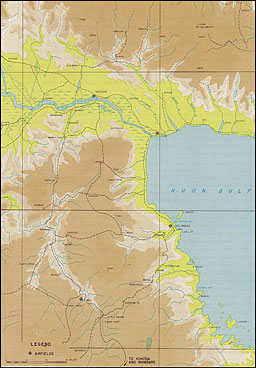

The town of Wau, which had been occupied by a small contingent of Australians since March 1942, was particularly desirable for the fulfillment of Japanese plans. (Plate No. 31) Strategically situated in the Bulolo Valley, it had access to the key inland trails leading northward to Lae and Salamaua, and southward to Mambare and Kokoda. In addition it had a small airfield already constructed and sites suitable for new strips. In Allied hands, it was a valuable outpost for the defense of Port Moresby, and a constant threat to the security of the Japanese positions at Lae and Salamaua. Conversely, if it were controlled by the Japanese, it would provide additional protection for their New Guinea positions and at the same time serve as a strategic intermediate base for a new drive to the south toward Port Moresby should the opportunity arise.

Once the Japanese decided to take Wau, they moved swiftly. While their troops were still fighting in Papua, other forces moved southward from Salamaua along the trails leading into Wau. On 27 January, just five days after the fall of Giruwa and Sanananda, they launched an attack against the

--101--

PLATE NO. 30

New Guinea-Solomons Area

--102-103--

weak Australian garrison occupying this strategic outpost.5

The situation was serious. Only the small Kanga Force, which had occupied the Wau area since March 1942, and a portion of the Australian 17th Brigade, which had recently arrived by air in anticipation of a possible enemy assault, were protecting the town. Bad flying weather had prevented the further dispatching of airborne troops and the thick jungle trails made any rapid overland reinforcement impossible. The Australian defenders, numerically inferior, attempted to hold off the enemy advance until more reinforcements could be sent, but they were gradually forced back toward the airstrip. The Japanese pushed forward until they were within 400 yards of the strip itself and had virtually surrounded the beleaguered Australian garrison.

A timely break in the weather at this critical point, however, enabled the Allies to fly in the remainder of the 17th Brigade from Port Moresby. On 29 January, plane after plane landed in rapid succession on the small airfield while the fighting was still in progress. During the first day of airborne reinforcement, fifty-seven landings were made on the Wau airstrip and for several days thereafter Allied air transports shuttled between Port Moresby and Wau carrying additional personnel and materiel to the sorely pressed garrison. Thus strengthened, the Australians soon shattered the enemy attack and moved forward. By 4 February the Japanese were in full retreat. Beaten and disorganized, they fled in disorder along the jungle trails, seeking refuge in their outpost at Mubo. It was later learned that more than one-fourth of the original enemy force which had set out to capture Wau was lost.

On 6 February the Japanese Air Force made a belated attempt to disrupt the Allied transportation system by attacking the Wau airstrip. Disproportionate losses, however, soon halted any further bombing efforts by the Japanese. This air attack concluded the struggle for Wau, leaving the town and the airstrip securely in Allied hands.

The Wau operation had once more clearly demonstrated the adaptability of air transport not only for conveying needed supplies and ammunition but also for the rapid landing of fully equipped troops under enemy fire. It again proved that air transport had become a strong and trusty weapon of the armed forces.6 The battle also marked the last attempt by the Japanese to seek new territory in New Guinea. From then on, in anticipation of a major Allied advance, their entire efforts were concentrated on strengthening the positions which they already occupied.

The action at Wau contributed in great measure to the success of the forthcoming Allied offensive in the region of the Huon Gulf and the drive against the vital Japanese bases at Salamaua and Lae. Soon after the Wau operation, the Allies began to deploy their forces in preparation for future assaults against the enemy. In March, Headquarters, 3rd Australian Division took over operations in the Wau area while the 15th Australian Brigade moved along another trail toward Bobdubi on the Francisco River above Mubo.

--104--

In April the Australians held positions in front of both Bobdubi and Mubo where they waited until other troops could be readied for a fullscale attack on Salamaua and Lae.

General Situation in Early 1943

General MacArthur, by skillful maneuver of his meager forces, had resisted and thrown back each Japanese attempt to press their initial advantages of surprise and power. Not satisfied with merely parrying the enemy's thrusts, he had, in addition, seized upon every opening to strike forward with adroit ripostes of his own. The Allies had accomplished much; in one year their strategic position had vastly improved and at the end of February 1943, General MacArthur was able to report:

Allied forces control Australia-Papua-Southeast Solomons-Fijis and the land and sea areas south of the line Buna-Goodenough-Fijis. Advanced airdromes are along the line Darwin-Moresby-Buna -Guadalcanal and these, with further development, will support initial operations toward the Bismarcks.7

Although the Allied successes in Papua and the Solomons were encouraging in themselves, they were only preliminary steps in the major effort necessary to destroy the enemy's military power.8 These successes did show, however, that the Japanese were being forced to relinquish the tactical initiative. In spite of the fact that General MacArthur still lacked the resources required for a full-scale offensive, he was now able to plan along lines which would bring his forces to decisive grips with the full strength of the Japanese war machine.

The problem presented was unique. Throughout the entire Southwest Pacific there was not a single concentration of Japanese strength in any particular area which could be brought to battle as in ordinary warfare. Japanese forces were placed to protect strategically vital ports and airdromes throughout an archipelago which extended over 900 miles from Manus in the Admiralties to New Georgia in the Solomons, and 400 miles from Kavieng on New Ireland to Lae on New Guinea. In this way the Japanese could command large expanses of territory by merely controlling certain key approaches. If these specific points, however, could be deprived of naval and air protection, they would become extremely vulnerable to amphibious assault and the Allies could, in turn, dominate and exploit these areas to their own advantage.

General MacArthur had long recognized the necessity of amphibious training for his troops. He knew that the Japanese were already trained and equipped for seaborne operations. Their campaigns into the Southwest Pacific had been planned far in advance, and their veteran troops had been given previous experience in amphibious maneuvers. By comparison, his own ground troops, including those employed in the Papuan Campaign, needed additional amphibious training before they could be effectively used in an over-water operation. His training program, however, had been held up by a chronic shortage of landing craft and other special equipment. In early 1943 this shortage was partially relieved by the assignment of the 7th Amphibious Force of the U.S. Navy9 and the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade of the U.S. Army to the Southwest Pacific Area. Each of these units was designated for a specific task. The 7th Amphibious Force,

--105--

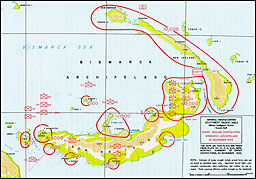

PLATE NO. 31

Strategic Location of Wau

--106--

equipped with transports, cargo vessels, and landing craft of all types, was to be employed for major amphibious movements, while the engineer brigade with small boats limited to a range of sixty miles was to be used for shore-to-shore operations.

Responsibility for amphibious training was given to Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, Commander of the 7th Amphibious Force, in January 1943. The program provided four weeks of intensive training for the battalion, regimental, brigade, and divisional combat teams, during which time they were taught to embark, proceed overseas, and land on hostile shores. A complete rehearsal was given each task force assigned to a particular assault mission immediately before the operation was launched.10 Ground, air, and naval units utilized the interval between campaigns to complete their standard training. Weaknesses brought out in combat were corrected, and newly arrived replacements were taught the techniques peculiar to tropical and jungle warfare. With a smoothly running amphibious training program, General MacArthur felt that his troops would soon be ready for a broadening of the offensive.

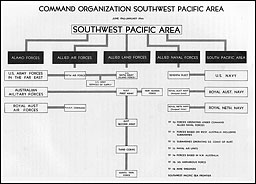

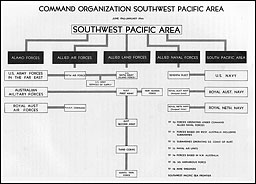

Southwest Pacific Area Command

In order to derive the maximum striking power from the different nations united in the fight against Japan, a rather complex command organization was worked out for the Southwest Pacific Area. (Plate No. 32) Originally the various national components were united for training and tactical employment but remained separate and distinct for all other purposes. The Australian First and Second Armies and the United States Sixth Army11 were under the operational control of Allied Land Forces which established separate task forces for each operation. New Guinea Force, which conducted the Papuan Campaign, was such a command and directed both Australian and American troops. In the spring of 1943, however, Alamo Force, composed entirely of United States units, was set up as an independent organization directly under General Headquarters and without an intermediate echelon of command. It actually comprised the Sixth Army. New Guinea Force remained under the Allied Land Forces, which by this action was relieved of the control of United States troops except as they were assigned for specific operations.

The United States Fifth Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force Command were assigned to Allied Air Forces, while the United States Seventh Fleet and units of the Royal Australian and Royal Netherlands Navies were grouped under Allied Naval Forces. These two commands remained united throughout all operations of the Southwest Pacific Area, but the naval units were divided into separate task

--107--

PLATE NO. 32

Command Organization, Southwest Pacific Area

--108--

forces according to the specific mission assigned. The Australian Military Forces, the Royal Australian Air Forces, and the United States, the Royal Australian, and the Royal Netherlands Navies were each responsible for the administration and supply of its own nationals. The United States Army Services of Supply, placed under United States Army Forces in the Far East, provided logistical support for the United States ground and air forces. The Sixth Army and the Fifth Air Force were also placed under the administrative control of USAFFE Headquarters which performed all staff duties incident to command, except those relating to strategic or tactical operations. General MacArthur, as Commander in Chief, Southwest Pacific Area, directed the combat employment and training of the combined armies, navies, and air forces, but at the same time, as Commanding General, United States Army Forces in the Far East, he was the direct commander of United States ground and air units.12

General Blamey was commander of the Australian Military Forces and Allied Land Forces; Admiral Carpender, of Allied Naval Forces and the Seventh Fleet ; General Kenney, of the Allied Air Force and the Fifth Air Force; and General Krueger, of the Sixth Army and Alamo Force. In spite of an apparent complexity, the command channels were clear and distinct. Each subordinate echelon had definite and specific duties and responsibilities, and was co-ordinated and controlled by General MacArthur and his staff. In addition, the forces of Admiral Halsey, Commander South Pacific Area, were to operate under general directives of the Commander in Chief, SWPA.13

General MacArthur described his headquarters in July 1943 as follows:

Complete and thorough integration of ground, air, and naval Headquarters within General Headquarters is the method followed with marked success in the Southwest Pacific Area rather than the assembly of an equal number of officers from those components into a General Headquarters staff. Land, air and naval forces each operate under a commander with a completely organized staff. Naval and air commanders and their staffs are in the same building with General Headquarters. The land commander and his staff are nearby.

These commanders confer frequently with the Commander-in-Chief and principal members of General Headquarters. In addition to their complete functions as commanders, they operate, in effect, as a planning staff to the Commander-in-Chief.

When operating in forward areas the same conditions exist.

The personal relationships established and the physical location of subordinate Headquarters make possible a constant daily participation of the staffs in all details of planning and operations. Appropriate members of General Headquarters are in intimate daily contact with members of the three lower Headquarters.

Air officers and naval officers are detailed as members of General Headquarters staff and function both in planning and operations on exactly the same basis as army officers similarly detailed. The problem in this area is complicated by the fact that it is an Allied effort. Australian and Dutch naval, air, and army officers have been assigned to General Headquarters.

General Headquarters is, in spirit, a Headquarters for planning and executing operations, each of which demands effective combinations of land, sea, and air power. General Headquarters has successfully developed an attitude that is without service bias. Although the physical location and staff procedures of all four Headquarters are of the utmost importance, it is only the determination that General Headquarters shall act as a General Headquarters rather than as the Headquarters of a single service that will produce the unanimity of action and singleness of purpose that is essential for the successful conduct of combined

--109--

operations.14

Battle of the Bismarck Sea

The defeat of the Japanese at Wau increased the danger to their general position in eastern New Guinea. Realizing that the enemy would become apprehensive about the security of his defenses below the Huon Peninsula, General MacArthur and his planning staff anticipated a major effort by the Japanese to reinforce their garrisons at Salamaua and Lae. Their assumption was further substantiated by numerous intelligence reports of a growing concentration of shipping in Rabaul harbor and of a noticeable increase in activity on enemy airfields along the probable convoy route.15

General MacArthur, accordingly, alerted his forces to be ready for a large-scale effort by the enemy to transport troops from Rabaul to eastern New Guinea. So certain were the Allies of an imminent convoy movement that General Kenney's air forces carried out actual practice maneuvers under conditions similar to those expected, reconnoitering the most advantageous routes of attack so that superiority could be attained at the point of combat. In addition, special preparations were made to carry out a new technique of skip bombing in the event of unfavorable weather and low cloud formations. Extensive rehearsals were carried out in February 1943 until the new method was perfected for the anticipated task.

Allied precautions were well taken. As expected, on 28 February a strong enemy convoy of 8 transports and 8 destroyers carrying the remainder of the 51st Division, certain key personnel, and various vital supplies for the New Guinea front, left Rabaul harbor. The convoy was spotted off Cape Gloucester on 1 March but unusually bad weather prevented an effective Allied strike. The next day, in spite of haze, rain, and thick clouds, the attack was launched according to rehearsed plans. Skip bombing practice had not been wasted. Driving in at low altitudes through heavy flak, General Kenney's planes skimmed over the water to drop their bombs as close to the target as possible. That morning the bombers left one transport sinking and scored several other hits.16 Adverse weather during the afternoon limited the effect of further strikes to minor damage. The battle was resumed on 3 March, about 30 miles southeast of Finschhafen, with an all-out attack by the Fifth Air Force bombers.17 In less than an hour after the main assault all the remaining transports were in a sinking condition and several

--110--

of the escorting destroyers were heavily damaged. The battle continued throughout the day and dawn of 4 March revealed a lone destroyer in the battle area which was soon sent to the bottom. It was a unique sea battle; not a single Allied vessel was involved.

The rain of bombs from the skies had been most destructive. Of the original convoy of 16 ships, all transports were sunk and only four destroyers survived.18 Captured documents later disclosed that more than half of the approximately 7,000 troops loaded on the convoy were lost. Of the survivors, only about 800 had managed to reach Lae. The entire load of provisions and materiel, including a large amount of airplane fuel and a four months' supply of food for 20,000 men, was totally destroyed.19 The forces in eastern New Guinea were thus deprived of supplies and reinforcements necessary to withstand the forthcoming Allied blows at Salamaua and Lae.

The destruction of the Bismarck convoy was a devastating blow to the Japanese20 which General MacArthur analyzed as follows:

We have achieved a victory of such completeness as to assume the proportions of a major disaster to the enemy. Our decisive success cannot fail to have most important results on the enemy's strategic and tactical plans. His campaign, for the time being at least is completely dislocated.21

Along with the loss of critical troops, supplies, and ships, the battle of the Bismarck Sea conclusively demonstrated that the Japanese could no longer reinforce the Salamaua-Lae area by cargo vessels or fast destroyer convoys. After this disaster, all attempts at running large transports into Lae were abandoned and the hungry enemy garrisons in eastern New Guinea had to be satisfied with the thin trickle of supplies and replacements carried in by destroyers, barges, or submarines. It was not until the battle for Leyte that the Japanese again attempted to bring in large reinforcements and supplies to beleaguered units within range of aerial bombardment. Control of the air over the sea had been definitely lost by the Japanese air forces.22

--111--

--112--

Henceforth, except for desperate counterattacks by isolated units, the Japanese were compelled to abandon all plans for the offensive in the Southwest Pacific.

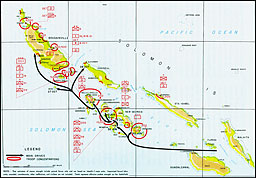

Final Plans

The final plan for the 1943 offensive was a carefully evolved synthesis of previously drawn plans, necessarily modified and adjusted to fit the resources available to the theater at the time.23 Briefly, the plan envisioned simultaneous operations along two lines of advance from Guadalcanal and from Papua, securing northeast New Guinea and the Solomons group, and converging to pinch off the Japanese strongholds at Rabaul and Kavieng. The immediate objective was the seizure of airfields along these routes from which to whittle down the enemy's strength and at the same time provide cover for Allied assaults.

To furnish air support for operations in the two sectors of intended advance, it was planned to occupy Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands and begin immediate development of airfields there. In New Guinea, meanwhile, an initial feint would be made at Salamaua to divert enemy forces to its protection. The main drive, however, would be made against Lae, seizing its valuable airstrips by a combined assault of an airborne force operating through the Markham Valley and an amphibious force moving along the coast from Milne Bay and Buna. Then Finschhafen and other bases in the Huon Gulf-Vitiaz Strait area would be taken by shore-to-shore movements.

In the Solomons, the forces of the South Pacific Area under the immediate command of Admiral Halsey were assigned the capture of the New Georgia island group. After attaining these objectives, both parts of General MacArthur's command, the Southwest Pacific and the South Pacific, covered and supported by the newly won bases, would push on to strike simultaneous blows against New Britain to the west and Bougainville to the east. Operations could then be undertaken to deprive Rabaul of naval support and airborne supply and to eliminate it as a threat to the Allied flank.24 (Plate No. 33)

Each subordinate command was delegated the responsibility of developing its own part of the designated operations. Liaison officers kept the various headquarters informed of what the others were doing and gave technical aid and advice. In addition, conferences between the planning staffs were held frequently. The rare problem that could not be solved by these methods was taken up by the commanders involved, or, if necessary, referred to General MacArthur for final decision.

These plans required extensive and careful preparation. Existing airdromes at Port Moresby and Buna were incapable of furnishing adequate fighter protection for an airborne assault in the Markham Valley, so additional airfields in the interior were developed at Berta Bena, Tsili Tsili, and in the Bulolo Valley. Bases on the coast through such points as the mouth of the Mambare River and Morobe Bay were constructed, and work was rushed on the road from the Lakekamu River to Wau. Further study of the facilities of the U. S. 2nd Engineer Special Brigade indicated that it could transport only one stripped brigade, approximately 3,000 men, which was insufficient for the planned assault upon Lae. It was decided, therefore, to move the entire Australian 9th Division from its staging area at Milne Bay in the larger craft of the U. S. 7th Amphibious

--113--

PLATE NO. 33

Operations Chart "ELKTON Plan," New Britain-New Ireland-New Guinea Area

--114-115--

Force. The 2nd Brigade was to be used by the boat and shore parties and for local shore-to-shore supply.

As the task forces completed their plans and assembled their troops, the engineers and other units of the United States Army Services of Supply and of the Australian Military Forces developed and improved airfields at Milne Bay, Buna, and Goodenough Island to provide close fighter cover and support for the projected amphibious movements and assaults. Supplies and equipment for the separate national forces were brought forward to the advance bases from the Zone of the Interior in Australia.

The logistical problem was extremely difficult, primarily because of the shortage of shipping. Some idea of its magnitude may be obtained from General MacArthur's report:

Operations are getting under way, involving a monthly dispatch from Australia to islands where combat is expected, including New Guinea, of an average of 600,000 ship tons for troops and cargo movements.... Much of this tonnage handled from the mainland of Australia to New Guinea and other islands must be transshipped on vessels of from 100-300 feet long, of shallow draught, and sometimes again to trawlers and similar small boats for island to island and coastal creeping supply operations....Water is the principal means of transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area. Roads between bases are non-existent in New Guinea; road and railroad capacity between bases on the mainland is negligible. As a result 95 per cent of supply and troop movements must be made by water. In considering the Southwest Pacific Area transportation problem, it must be remembered that it is 1500 miles from Port Moresby to Milne Bay. Our operations are already scattered along 300 miles of coastline on the north of New Guinea and will more and more extend to numbers of small islands from the advanced bases in New Guinea, frequently involving runs of from 100, 200 and 300 miles across water. All floating equipment found in Australia has been sent into this area, but Australia is a sparsely settled, under equipped country that has already exceeded expectations in contributing as she has 40 coastal vessels (cargo) and several scores of trawlers, fishing smacks, and similar craft.... Attention is invited to the fact that the enemy frequently assembles 250,000 or 300,000 tons of merchant shipping, exclusive of small boats in Rabaul Harbor alone. If we are to amass sufficient force to overcome a force maintained by this much tonnage, it can well be expected that our tonnage be far greater....25

Reconnaissance parties, aircraft, and submarines intensified their efforts to gather information concerning landing beaches, terrain, ground and aerial concentrations, shipping and defensive installations. As at Guadalcanal, patrols of the Allied Intelligence Bureau operated deep behind the enemy lines, and "coast watchers" were stationed at strategic points to observe and report on hostile activities. Aircraft and submarines conducted regular searches of the Bismarck and Solomon Seas to check shipping, airdromes, and troop concentrations. Each task force had trained scouts, who were landed from submarines and motor patrol boats for tactical reconnaissance of the immediate objectives.26

Every measure was taken to insure the completeness of final preparations. The 7th Amphibious Force concentrated its transports and landing craft at Townsville and Milne Bay; other surface and sub-surface vessels of Allied Naval Forces protected supply convoys and attacked enemy shipping. The Allied

--116--

Air Force stepped up its attacks on airdromes from the northern Solomons through New Ireland and New Britain to Wewak on New Guinea, destroying or damaging hundreds of Japanese planes in combat and on the ground. Heavy air raids on Koepang, Ambon, Timor, Tanimbar, and other bases in the Netherlands East Indies were carried out to deceive the enemy as to the main direction of the offensive. Increased dummy signal traffic in code through radios at Darwin, Perth, and Merauke helped to convince the Japanese that at least a diversionary attack was to be mounted from northwestern Australia. No step was overlooked which might aid the forthcoming operations.

Woodlark and Kiriwina

The 1943 offensive was initiated by General Krueger's Alamo Force which was charged with the task of occupying Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands. According to the over-all plan, these two islands were to be developed as air bases to cover the advance of both the Southwest Pacific and South Pacific Forces.27

It was the first amphibious landing movement assigned to the Southwest Pacific Area and, although neither of the islands was held by the enemy, much advance preparation was necessary. The garrison and construction troops for Woodlark were furnished by the South Pacific Command and arrived at Townsville in northeastern Australia between 21 May and 4 June. The units for Kiriwina were scattered along the Australian mainland and at Port Moresby. Both forces were transported to Milne Bay for staging purposes and movements were carefully co-ordinated to avoid interference with essential supply activities. The difficulties presented by a poor road net and the inadequate loading facilities at Milne Bay further complicated the problem. The concentration of troops for the amphibious operation was accomplished in good time, however, and the target date for the main landing was set for 30 June.

Operations were carried out as scheduled. On 23 June, advance engineer and survey construction parties were landed on both islands to prepare for the arrival of the main force. On 30 June, while New Guinea Force was holding the enemy's attention by landings along the New Guinea coast near Nassau Bay and Admiral Halsey's forces were moving toward Rendova Island on New Georgia, Alamo Force carried out the complete occupation of Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands.

Enemy reaction was limited to aerial reconnaissance and one or two feeble bombing raids. Intense attacks by the Allied Air Force on hostile bases during previous months had weakened the enemy's power to organize effectual opposition to the troops of Alamo Force. Besides, the Japanese could not divert their attention from areas of the concurrent Allied operations in New Guinea and New Georgia.

Ground and antiaircraft defenses on Woodlark and Kiriwina were quickly installed. Work on the airstrips proceeded rapidly, and by 24 July the 67th Fighter Squadron of the South Pacific Command was ready for missions based at Woodlark. On 18 August, the 79th RAAF Fighter Squadron was ready for action at Kiriwina.

New Georgia

On the eastern crescent of the Allied offensive, the South Pacific Force was carrying out its attack on New Georgia Island in the northern Solomons. Areas which were only lightly

--117--

defended by the enemy had been selected for the initial landings. Enemy ground troops were strongly entrenched around Munda on New Georgia and at Vila on Kolombangara; other enemy outposts were stretched from Vanganu Island to Vella Lavella. The minor concentrations of Japanese forces, except for those at Vella Lavella, were to be by-passed.

On 21 June, a small group of Marines made a preliminary landing at Segi Point on the southeast tip of New Georgia. On 30 June, forces of the 43rd Division went ashore at Wickham Anchorage on southeast Vanganu Island and at Rendova Harbor. The Japanese, apparently, were not expecting Allied landings at these points since the first incursions were virtually unopposed on land.28

Enemy reaction in the air and on the sea, however, was strong and rapid. During the first five days of the Allied operations, the Japanese attacked shipping and shore positions with over 315 aircraft of which approximately 155 were destroyed. Hostile naval forces were sent in with supplies and reinforcements. In two naval engagements in the Kula Gulf on 6 July and 12 July, several Japanese cruisers and destroyers were put out of action.29

Despite these attempts to check Allied progress, the 43rd Division on Rendova drove ahead to eliminate all pockets of enemy resistance. Artillery was set up on the Rendova coast in preparation for the assault on the main Japanese stronghold at Munda across the Blanche Channel. On 2 July, units of the Division crossed over from Rendova to secure beaches east of Munda airfield and six days later a coordinated attack was made on Munda itself.

The enemy defended his positions stubbornly, however, and Allied reinforcements from the 25th and 37th Divisions were brought into the struggle. After severe fighting and heavy casualties on both sides, Munda fell to the Allies on 5 August. The northern portion of New Georgia was cleared by Marine units which had landed at Rice Anchorage on 5 July.

The Japanese evacuated their forces on Kolombangara by barge and destroyer between 28 September and 4 October. By 10 October, New Georgia and its adjacent islands, including the airdrome at Vila, were in Allied hands. Offensive operations against the enemy were progressing smoothly and after the capture of Munda General MacArthur stated:

We are doing what we can with what we have. Our resources are still very limited, but the results of our modest but continuous successes in campaign have been cumulative to the point of being vital. A measure of their potentiality can be obtained by imagining the picture to have been reversed, with the enemy capturing Guadalcanal and besieging Port Moresby rather than we in possession of Munda and at the gates of Salamaua. Such a contrast might well have meant defeat for us in the war for the Pacific.

The margin was close but it was conclusive. Although for many reasons our victories may have lacked in glamorous focus, they have been decisive of the final result in the Pacific. I make no predictions as to time or detail, but Japan on the Pacific fronts has exhausted the fullest resources of concentrated attack of which she was capable, has failed, and is now on a defensive which will yield just in proportion as we gather force and definition. When that will be I

--118--

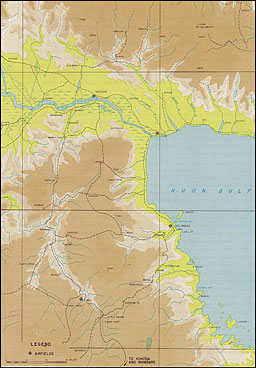

PLATE NO. 34

Operations, Nassau Bay to Salamaua

--119--

do not know, but it is certain."30

Nassau Bay to Salamaua

The plan to advance in northeast New Guinea and seize the Huon Peninsula necessitated comprehensive preparations to cope with the many complex terrain and hydrographic factors involved. Large ship-to-shore movements in the seas adjacent to New Guinea were impractical because of shallow, restricted waters and the danger of major losses from enemy air attack. Shore-to-shore advances were limited by the shortage of small landing craft and overland operations through the mountains were hampered by the impossibility of maintaining a strong supply line. To surmount these problems, it was planned to conduct a combined amphibious, airborne, and overland drive from the east and west, utilizing each type of maneuver where most practical and co-ordinating the over-all operation to obtain maximum striking power. Again the keynote of General MacArthur's policy was the use of his land, naval and air forces as a composite team.

Early in May, he issued Warning Instructions No. 2 which directed New Guinea Force to seize and occupy the area containing Salamaua, Lae, Finschhafen, and Madang. Under the warning order, New Guinea Force was given the code name "Phosphorous" and put under the command of General Blamey with General Herring named as his deputy.31

Lae, the gateway to the Huon Peninsula, was the first main objective for this new advance in New Guinea. This enemy strong-hold was protected not only by well-prepared defenses of its own but also by a cordon of fortified positions at Mubo, Bobdubi, Komiatum, and Salamaua which stood guard over its approaches. (Plate No. 34) It was decided that a United States amphibious force would be sent along the eastern coast of New Guinea to effect a landing which would permit a junction with the Australians already operating along the outskirts of Mubo. The boats of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, selected to transport the troops and equipment, were limited in range, making it necessary to debark within sixty miles of Morobe, a port of departure secured by the Allies early in April. Nassau Bay was chosen as the point of the proposed amphibious landing. The United States troops were to join the Australian 17th Brigade in a combined attack on Mubo while the 15th Brigade moved forward from the Missim area to take Bobdubi Ridge to the north between Mubo and Salamaua.

On 30 June, while other Allied forces were striking in the Trobriands and at New Georgia, a reinforced battalion of the United States 162nd Infantry landed at Nassau Bay. The area was unoccupied by the enemy and subsequent resistance was light. While the 15th Brigade drew enemy attention to its attack on Bobdubi, United States troops, according to plan, drove west from the coast to link forces with the Australians at Mubo on 14 July. With the aid of heavy artillery bombardment and effective air support from the 5th Air Force, the Allies succeeded in occupying Mubo and pushing the surviving Japanese back toward Salamaua.

The Japanese took up new positions along the line Bobdubi-Mt. Tambu-Komiatum, where the Allied advance temporarily halted. Meanwhile, two more battalions of the 162nd Infantry landed at Nassau Bay and moved up to Tambu Bay where they encountered difficult terrain and powerful enemy defenses around Roosevelt Ridge. The Allies soon maneuvered

--120--

to cut the Japanese line of communications, however, and began to encircle their positions from the flanks and to the rear.

The Japanese tried vainly to prevent the steady closing of the Allied trap by desperate counterattacks from Mt. Tambu and Roosevelt Ridge. They knew that if any of their outer defenses were pierced the Allies would command dominating positions from which to bombard Salamaua itself with direct fire. The Allied forces continued to close in, nevertheless, and on 19 August the Japanese abandoned Mt. Tambu and Komiatum Ridge and retreated to a line along the Francisco River. Salamaua now lay open to assault.

General MacArthur, however, had not planned to take Salamaua immediately. Its airfield had been rendered useless and the town proper was of little importance to operations. The main purpose of the Allied attack on this small isthmus on the east coast of New Guinea was to siphon off enemy strength from his Lae defenses and lure his troops and supplies southward to be cut to pieces on the Salamaua front. It was intended to deceive the Japanese into believing that Salamaua was the prime objective of the Allied advance and this strategy was later to prove most successful.32 Meanwhile, under cover of the Salamaua operations, the Allies were preparing for the principal drive to capture the strategically important town of Lae. Accordingly, Salamaua was not to be taken until the assault on Lae was actually underway.

Air Attack on Wewak

When the spotlight of the Pacific Theater focused on operations in the New Guinea area, Japanese Imperial General Headquarters felt that air power in that region had to be considerably strengthened. Consequently, on 28 July, orders were issued for the formation of the Japanese Fourth Air Force.33

The Allied Fifth Air Force, however, suspecting some such move by the enemy, intensified its assaults on key Japanese air bases. On 17 and 18 August, while the Japanese were consolidating their forces on the northeast New Guinea coast to carry out their assigned mission, a strong formation of Allied planes struck suddenly at Wewak. Heavy attacks on its major airdromes destroyed large numbers of planes caught on the ground.

As a result of this successful surprise attack, the sailing of enemy convoys intended to reinforce the Wewak and Hansa Bay garrisons, was rendered next to impossible owing to lack of air cover.34 In commenting on the Wewak raid, General MacArthur said:

--121--

It was a crippling blow at an opportune moment. Numerically the opposing forces were about equal in strength, but one was in the air and the other was not. Nothing is so helpless as an airplane on the ground. In war, surprise is decisive.35

Smaller raids upon this base, Hansa Bay, and other positions in New Guinea were continued daily. Enemy interception grew lighter and the quality of his pilots deteriorated steadily after the heavy losses suffered in this sector and in the Solomons.

Nadzab and Lae

Preparations for the Lae operation were intensified during this period. On 20 August General Blarney arrived from Australia to take personal command of New Guinea Force. The amphibious and airborne training of the troops was completed, full-dress rehearsals were held, and the necessary equipment brought forward for loading. A strong United States carrier task force in the South Pacific sortied from Espiritu Santo and Efate in the New Hebrides and began round-the-clock raids on southern Bougainville to divert enemy attention to possible Allied assaults in that area. At the same time, PT boats and submarines struck at enemy barges along the coast and protected Allied waterborne movements against surface and subsurface attack.

The development of the hard-won Allied port at Buna had proceeded rapidly. It was to be the base of operations for the Australian 9th Division in its attack on the enemy's left flank. Actually, the timing of the Lae operation depended to a great extent upon the speed with which Buna could be built up as an intermediate supply base and staging area on the road from Milne Bay to the Lae beaches.36

On 1 September, the Australian 9th Division embarked in the transports and assault craft of the 7th Amphibious Force at Milne Bay. After a stop at Buna for reinforcements, fueling, and a final check, the landing force moved forward. On 4 September, under cover of continuous Allied air strikes at Wewak, Hansa Bay, Alexishafen, Madang, and New Britain, the main attack on Lae was launched. The assault troops hit the beaches at Bulu Plantation and at the mouth of the Busu River, less than twenty miles from Lae. (Plate No. 35) Minor opposition from enemy snipers was quickly eliminated and the troops drove on up the coast toward Lae itself.

At the same time that the Allied amphibious assault was being carried out east of Lae, a bold scheme was in progress to strike the enemy simultaneously on his right flank. It was planned to fly the Australian 7th Division directly from Port Moresby and land it in the Markham Valley to attack Lae from the west. The success of this maneuver depended upon the seizure of a pre-war emergency landing field located at Nadzab across the Markham River. The previously developed airstrips at Tsili Tsili and Wan were to provide the necessary fighter cover for such an airborne maneuver.

On 5 September, the United States 503rd Parachute Regiment, accompanied by General MacArthur himself, took off from Port Moresby on the first major jump of United States paratroopers in the Pacific War. "I did not want our paratroops to enter their first combat fraught with such hazard," said General MacArthur, "without such comfort as my presence might bring to them."37 Trans-

--122--

PLATE NO. 35

Nadzab and Lae

--123--

port after transport poured out its cargo of fully equipped paratroopers upon the vital airstrip. Watching the multi-colored parachutes spread themselves over the valley, General MacArthur felt the satisfaction of seeing this daring operation carried out with smooth precision. Even before he left the scene, the ground was being prepared for the big transports as flame throwers began to eat away the large patches of tall kunai grass. On the next day, the first of the planes bearing elements of the 7th Division landed on the runway to discharge its precious load of troops and equipment.38

The Allied circle around the enemy at Lae began to tighten rapidly. Advance troops of the 7th Division joined the paratroopers and drove along the Markham Road to approach Lae from the west. The 9th Division hammered in from the coast while the Allies increased the pressure from the air and on the Salamaua front to the south. On 11 September the Francisco River line was breached and the grim defense of Salamaua was smashed. The Allies closed in on Lae from all sides.

The Japanese were surrounded except for one narrow route of escape northward through the dense jungles and almost impassable mountain trails of the Huon Peninsula. As the Allied noose gradually choked them off from all hope of aid, the Japanese yielded their positions and, discarding almost all equipment, began a precipitous flight through jungle and mountains towards Kiari in a desperate effort to escape complete annihilation. On 16 September, Lae was occupied by the Allies. Another valuable link was forged in the chain of airbases that would eventually encircle and render helpless the powerful Japanese war machine.

Securing the Huon Peninsula

While the airstrip at Lae was being developed as a new forward base for Allied transport planes, New Guinea Force moved onward. Its next objective was Finschhafen-a busy enemy port on the tip of the Huon Peninsula. A keystone in the arch of the Japanese defenses guarding the western side of the strategic Vitiaz Straits, it was a valuable prize to be plucked from enemy hands.

Plans for the assault of Finschhafen had been mapped well in advance. Immediately after the fall of Lae, the 20th Brigade of the Australian 9th Division which had made the initial Lae landing, started on its next mission. On 22 September it rounded the jutting Huon peninsula and landed just north of Finschhafen. (Plate No. 36) The beachhead was secured against stiff opposition and the Allied troops, reinforced by another battalion, advanced toward their objective. Moving steadily on against stubborn but hastily prepared enemy counterattacks, Allied forces occupied Finschhafen on 2 0ctober.39 The Japanese retreated northwest to Satelberg where, taking up strong defensive positions, they contested the Allied

--124--

advance. Enemy lines of supply and communication were maintained from bases at Sio and Gusika and reinforcements were brought in during the month of October to check the Allied drive.

As one part of New Guinea Force carried out amphibious operations along the coast of the Huon Peninsula, another part was cutting inland below the enemy along the Markham Valley. Elements of the Australian 7th Division moving up from Nadzab seized Kaiapit, west of the Leron River, on 18-19 September. From there they went on to Gusap and thence to Dumpu which was taken on 4 October. These latest conquests provided new sites for the development of advanced airfields which would give the Allies an additional string of important operational airbases stretching from Tsili Tsili through Nadzab, Kaiapit, and Gusap to Dumpu.

On 25 November, New Guinea Force resumed its drive on the Huon Peninsula and pressed forward against continuing bitter resistance to occupy Satelberg. Moving north from Satelberg, it pushed on to take Wareo on 8 December.

The capture of Finschhafen and the subsequent drive up the New Guinea coast together with the simultaneous air-ground movement of 200 miles up the Markham Valley through the center of New Guinea gave the Allies control of the entire Huon Peninsula. The Allied maneuver outflanked and contained all important enemy centers on the Peninsula and rendered impotent his numerous positions and installations along the northeast coast of New Guinea. The speed of this double envelopment apparently caught the enemy unprepared and resulted not only in the serious dislocation of his grip on New Guinea but caused him enormous losses of men and material which he found impossible to replace.

Bougainville

Admiral Halsey's South Pacific Force, meanwhile, was engaged along the other crescent of advance in the northern Solomons. Originally, it had been planned to capture and consolidate the airfields near Faisi in the Shortland Islands and near Buin on southern Bougainville to cover a further advance to Kieta on the east coast. (Plate No. 37) Heavy concentrations of enemy strength at these two places, however, later made it advisable to amend the plan in favor of by-passing these enemy strongholds and making an incursion farther north at Torokina along Empress Augusta Bay. Aircraft could then neutralize Buka to the north while naval forces could close the sea route through St. George's channel to Rabaul and at the same time cover the projected assault on western New Britain.

To assist the operations of the South Pacific Force, bombers from the 5th and 13th Air Forces, escorted by fighters from Kiriwina and Woodlark, were to attack airdromes and shipping at Rabaul and Buka from the middle of October to 6 November. The South Pacific Force, shielded by these raids, would then occupy Treasury Island and northern Choiseul about 20 October to establish radar and motor torpedo boat bases for the subsequent attack against Empress Augusta Bay.40

The daylight air raids on Rabaul by General MacArthur's air forces commenced with the great strike on 12 October. To inflict maximum damage upon the enemy, the attack was timed to take place when observation photographs disclosed the largest number of enemy planes on the ground. Just as the right wing of the Japanese air force had been smashed at Wewak,

--125--

PLATE NO. 36

The Envelopment of the Huon Peninsula

--126--

PLATE NO. 37

Allied Operations and Estimated Enemy Dispositions, Solomon Islands, 30 June 1943

--127--

General MacArthur hoped this time to destroy their left wing at Rabaul. The division of enemy air power into groups operating from these two widely separated bases made it possible for him to throw his entire available air strength alternately against one flank and then the other, thereby acquiring in each case superiority at the point of attack.

The Allied strike at Rabaul like the one at Wewak again caught Japanese planes on the ground, severely crippling the enemy's air strength and greatly damaging his merchant and naval units in the harbor. Continuous subsequent raids upon Lakunai, Vunakunau, Tobera, and Rapopo, the four major fields at Rabaul, greatly reduced Japanese air strength and contributed to the success of Admiral Halsey's attack in the northern Solomons.

According to the revised plan, the Allies moved forward 200 miles from New Georgia to carry out the projected landings in central Bougainville. On 2 November the United States 3rd Marine Division hit the beaches at Torokina on the northern shore of Empress Augusta Bay and pushed inland against relatively light opposition. The Japanese apparently did not expect an attack at this point. Their main forces concentrated at Buin and Buka were cut off by mountains, swamp, and jungle from the Allies at Torokina, and were consequently unable to counterattack effectively on land.41 The Allies by their by-passing maneuver thus outflanked the Japanese on southern Bougainville and stood squarely athwart their supply line to that area.

Scattered hostile naval and air attacks failed to retard the rapid development of the Torokina beachhead. During the month of November, three enemy naval task forces were intercepted and driven back with substantial losses. The Marines, reinforced by the 37th Division, formed a defensive cordon around the airfield sites as a safeguard against probable counterattack. Enemy counterefforts, however, hampered by the difficulties of the intervening terrain, could not be mounted until March. When his anticipated attacks did materialize they were completely crushed. After that, the Japanese contented themselves with small, ineffective raids which continued sporadically until the end of the war.

The strategic aim of the Bougainville operation had been accomplished with the investment of Empress Augusta Bay. The Allies now possessed new airfields within 250 miles of Rabaul to help complete its isolation and neutralization.

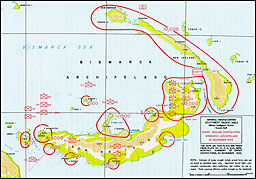

New Britain

With the ousting of the Japanese from the Huon Peninsula, General MacArthur had secured domination over the western approaches to the Vitiaz Straits. To remove completely all threats of enemy interference with his operations in those strategic waters, he decided to lose no time in completing his conquest of the Straits and seizing control of its eastern shores. He accordingly directed Alamo Force to occupy Cape Gloucester on the southwestern tip of New Britain, setting the target date initially as 20 November. This date was based upon the assumption that the airdromes in the Lae-Finschhafen-Markham Valley area would be fully developed and capable of providing close support and cover. On 19 November, one regimental combat team was to seize an airfield

--128--

site at Lindenhafen Plantation near Gasmata on the south coast and then prepare to neutralize the surrounding region and prevent its use by the enemy. This operation would protect the southeast flank of the forces involved in the main effort against Cape Gloucester which was to be launched six days later by a combined amphibious and airborne attack on the other side of New Britain.

42

Unforeseen developments, however, necessitated some changes in the original plans. The engineers reported in late October that the supporting airdromes could not be completed on schedule. The attack upon Lindenhafen, therefore, was postponed until 2 December and that upon Cape Gloucester until 26 December.43 Intelligence reports received in November indicated that the Japanese garrison in the Gasmata area had been reinforced and was expecting an attack but that other areas, particularly Arawe, were weakly held. (Plate No. 38) In addition, it was decided that air facilities at Gasmata were not essential to the success of the operation. Under these circumstances, the attack was cancelled and instead it was planned to capture Arawe on Cape Merkus to the west in order to provide the necessary motor torpedo boat base for the protection of the main convoy movement to Cape Gloucester. The seizure of this port was therefore substituted for Lindenhafen, and a target date of 15 December was assigned to allow Alamo Force adequate time to provide for the change in plan.44

In preparing for the New Britain landings, the heavy concentration of enemy air strength on the Rabaul airfields constituted a serious menace to Allied operations. In spite of repeated raids on their airdromes, the Japanese continued to send planes aloft in considerable numbers. During the month of November, particularly, their efforts in the air reached a new peak of activity, indicating that plane reinforcements in substantial strength were arriving at Rabaul, Kavieng, Wewak, Hollandia, and Madang.45

This resurgence of enemy air power presented an added problem in the guarantee of adequate air coverage for the New Britain operation. There was no illusion that the naval convoy would escape heavy Japanese bombing attacks. To enable the fighter planes of the Allied Air Force, which were based on widely scattered fields, to rendezvous over Vitiaz Straits and maintain a continuous air umbrella over the convoy, General Kenney needed advance reports of Japanese air sorties against Allied landing forces at Arawe and Gloucester. General MacArthur's G-2 had anticipated this need and had taken steps to develop a comprehensive radio warning net of intelligence agents behind the Japanese lines. Three months prior to the Allied invasion of New Britain the U. S. Submarine Grouper had landed 26 Allied Intelligence Bureau operatives and 27 specially trained natives on the island.46 These operatives had slowly infiltrated inland, and on the day of the

--129--

PLATE NO. 38

Enemy Ground Dispositions, Bismarck Archipelago, 30 November 1943

--130--

Allied landings they were in strategic positions to report on enemy activity and to give ample notice of oncoming enemy air formations.

The requisite troops and amphibious craft of Alamo Force were concentrated at Milne Bay, Buna, and Goodenough Island, while Allied planes began preparatory bombardment. Over 1,500 sorties were flown against Cape Gloucester alone during December and 3,700 tons of bombs were dropped. Gasmata and other positions on the south coast of New Britain were raided frequently, but to avoid alerting the enemy Arawe was not attacked until the day preceding the landing.

On 15 December, the U. S. 112th Cavalry Regiment, with strong air and naval support, went ashore at Arawe. Ground resistance was ineffectual and beachhead positions were rapidly consolidated. As predicted by initial intelligence forecasts, however, the Japanese attempted to strike back swiftly and forcibly in the air. An estimated 100 planes appeared over Arawe within three hours after the landing and from the 15th through the 17th approximately 350 enemy sorties were made in one of the largest defensive air operations which the Japanese had thus far engaged upon in the Southwest Pacific.47 Allied fighters, however, forewarned of the impending strikes, scored heavily against each raid.48 The Japanese nevertheless continued to expend their plane strength against Arawe until it became apparent that the prime interest of the Allies lay elsewhere.

Persistent Allied raids upon Cape Gloucester marked it clearly as General MacArthur's next objective. Even after the Japanese became aware of the Allies' true intention they could do little to protect this vital position which guarded the Vitiaz Strait and the lines of communication between Rabaul and New Guinea. The Allied aerial and submarine blockade restricted troop movements to small craft operating under cover of darkness and prevented the concentration of air and naval forces in sufficient strength to resist an attack. The Japanese attempted to reinforce their garrison from the ground troops at Rabaul, but this reinforcement was inadequate to counter the force pitted against it.

The mounting evidence of enemy weakness caused Alamo Force to cancel the airborne phase of the Gloucester operation and to rely entirely upon amphibious assault. On 26 December, two combat teams of the U. S. 1st Marine Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, covered and supported by a heavy naval and air bombardment, landed on the beaches southeast and southwest of Cape Gloucester. The bombardment had proved very effective and the beachheads were secured against minor initial opposition. The main difficulties were presented by the narrow beach, which heavy rains had converted into a sea of mud, and the thick swamp and jungle beyond. At the end of the first day the Marines had established a perimeter approximately goo yards in from the shore against stiffening resistance. As at Arawe, air reaction was initially strong and determined but after continued successful interception by Allied fighters enemy air activity virtually ceased by the end of December.49 Both

--131--

flanks of the vital Vitiaz Straits had been secured, opening the waters of this strategic highway between the Solomon and Bismarck Seas for unrestricted use in the furtherance of Allied plans.

Saidor

After the recapture of Satelberg and Wareo, New Guinea Force continued to advance along the Huon Peninsula against a steadily retreating enemy. The Japanese, with their supply lines rapidly disintegrating under sweeping Allied assaults, picked their way westward toward Sio and Madang. They were given no opportunity for respite or consolidation; their weary troops were compelled to resume their retreat once more as the Australians moved into Sio on 14 January 1944.

General MacArthur intended that this withdrawal should cost the enemy as high a price as possible. To cut off the main route of retreat and at the same time speed the Allied advance, he directed Alamo Force to make an amphibious landing at Saidor, midway between Sio and Madang.50

The landing was made on 2 January and the United States troops turned eastward to meet the fleeing enemy. General MacArthur described the predicament of the Japanese when he reported:

We have seized Saidor on the north coast of New Guinea. lit a combined operation of ground, sea and air forces, elements of the Sixth Army lauded at three beaches under cover of heavy air and naval bombardment. The enemy was surprised both strategically and tactically and the landings were accomplished without loss. The harbor and airfields are in our firm grasp. Enemy forces on the north coast between the Sixth Army and the advancing Australians are trapped with no source of supply and face disintegration and destruction.51

The Japanese, caught between the closing pincers of the two advancing forces, abandoned the main route of retreat and, trying desperately to reach Madang, scattered in chaotic flight into the jungles.52 The hundreds of exhausted and starved bodies of Japanese discovered later along the ridges and mountain trails attested to the fact that the jungle had done its part in completing the work of the Allies. The last enemy soldier was squeezed off the Sio-Saidor road when elements of the Alamo and New Guinea Forces made contact on 10 February.53

Saidor was developed as an advance air and naval base to assist in the further conquest of New Guinea and for penetration into the Bismarck Sea, soon to be the next zone of Allied operations.

Objectives of 1943 Achieved

The year 1943 had fulfilled its early promise. The propitious victory at Buna had presaged the Allied conquests to come. In marked contrast to the slow, uphill struggle of the preceding year, 1943 witnessed long strides by the Allies deep into enemy territory. The goals set at the beginning of the year had been successfully achieved. On his left flank, General MacArthur had moved on from Buna according to plan, seizing in succession Salamaua,

--132--

Lae, Finschhafen, and the entire Huon Peninsula. His forces were rolling back General Adachi's Eighteenth Army at an accelerating pace all along the coast of New Guinea. On his right flank, the capture of Arawe and Gloucester Bay had placed the southern end of New Britain in his hands. Farther to the east, the Allies controlled the entire stretch of the Solomon Islands and the waters of the Solomon Sea.

Rabaul was being steadily emasculated by a growing Allied air arm which slashed constantly at its vital airfields and harbor installations. Enemy thrusts from that once powerful stronghold were becoming weak and ineffectual and by the end of February 1944, Rabaul had "no air support whatsoever." In spite of replacements and reinforcements the once-powerful "Japanese air force in this area had been driven to the point of extinction."54 The gradual decimation of the enemy's landbased air power by the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces sharply decreased his ability to defend his vital sea lanes and opened the way for Allied naval craft to advance in increasing strength. It was these unrelenting and punishing attacks against major Japanese airfields and ground installations that won the battle in the skies and gradually destroyed the enemy air force in the New Guinea-Solomons area.

The Japanese at the opening of the year had held an advanced line running from Salamaua and Lae across southern New Britain and the Solomon Sea to New Georgia. Now their ground forces were pushed back to Madang, Rabaul, and Kavieng. In the air, the power of the Allied Air Force was increasing rapidly and could drive the enemy from the sky at almost any chosen point. On the sea, Allied Naval units had demonstrated that they could cope with any threat to amphibious operations and defeat the enemy wherever he chose to give battle.

The Japanese had suffered heavily in men and materiel. Huge amounts of discarded and abandoned supplies, guns, and ammunition marked the veering paths of their confused retreat as they were forced from one position after another. Thousands of their dead, killed in battle or stricken by starvation and disease, were left strewn on the battlefields and along the jungle trails. Additional thousands of troops were pocketed on Bougainville, Buka, Choiseul, and the Shortlands, their sting removed by isolation and their whole attention occupied with maintaining their own sustenance. Their transport and supply ships were sunk in increasing numbers as Allied planes and submarines exacted an ever-rising toll for their passage. Clearly, the Japanese had lost the power to conduct any further large-scale offensives in New Guinea.

As supplies kept coming into the Southwest Pacific Area and the shortages which shackled his every plan were gradually being removed, General MacArthur prepared to launch heavier blows against the Japanese.

--133--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (4) **

Next Chapter (6)