The Anzio Landing

22-29 January

AFTER THE BATTLE. The central square of Cisterna, 26 May 1944

In the early morning hours of 22 January 1944, VI Corps of Lt. Gen.

Mark W. Clark's Fifth Army landed on the Italian coast below Rome and

established a beachhead far behind the enemy lines. In the four months

between this landing and Fifth Army's May offensive, the short stretch

of coast known as the Anzio beachhead was the scene of one of the most

courageous and bloody dramas of the war. The Germans threw attack after

attack against the beachhead in an effort to drive the landing force

into the sea. Fifth Army troops, put fully on the defensive for the

first time, rose to the test. Hemmed in by numerically superior enemy

forces, they held their beachhead, fought off every enemy attack, and

then built up a powerful striking force which spearheaded Fifth Army's

triumphant entry into Rome in June.

The story of Anzio must be read against the background of the

preceding phase of the Italian campaign. The winter months of 1943-44

found the Allied forces in Italy slowly battering their way through the

rugged mountain barriers blocking the roads to Rome. After the Allied

landings in southern Italy, German forces had fought a delaying action

while preparing defensive lines to their rear. The main defensive

barrier guarding the approaches to Rome was the Gustav Line, extending

across the Italian peninsula from Minturno to Ortona. Enemy engineers

had reinforced the natural mountain defenses with an elaborate network

of pillboxes, bunkers, and mine fields. The Germans had also

reorganized

their forces to resist the Allied advance. On 21 November 1943, Field

Marshal Albert Kesselring took over the command of the entire Italian

theater; Army Group C, under his command, was divided into two

armies, the Tenth facing the southern front and also holding

the

Rome area, and the Fourteenth guarding central and northern

Italy. In a year otherwise filled with defeat, Hitler was determined to

gain the prestige of holding the Allies south of Rome.

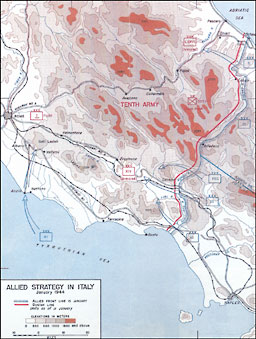

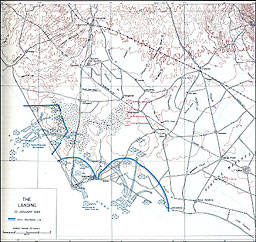

Map No. 1

Italian Front, 15 January 1944

Opposing the German forces was the Allied 15th Army Group, commanded

by Gen. Sir Harold R. L. G. Alexander, with the U.S. Fifth Army

attacking on the western and the British Eighth Army on the eastern

sectors of the front. In mid-December, men of the Fifth Army were

fighting their way through the forward enemy defensive positions, which

became known as the Winter Line.1

--1--

THE ANZIO BEACHHEAD TERRAIN, looking northeast over the flat

plain toward Velletri Gap. In the foreground is the town of Anzio.

Nettuno is on the right. (Photo taken in September 1944.)

Braving the mud, rain, and cold of an unusually bad Italian winter,

scrambling up precipitous mountain slopes where only mules or human

pack-trains could follow, the Allied forces struggled to penetrate the

German defenses. By early January, Fifth Army troops had broken through

the Winter Line and had occupied the heights above the Garigliano and

Rapido Rivers, from which they could look across to Mount Cassino, with

Highway No. 6 curving around its base into the Liri Valley. Before them

were the main ramparts of the Gustav Line, guarding this natural

corridor to the Italian capital. Buttressed by snow-capped peaks

flanking the Liri Valley, and protected by the rain-swollen Garigliano

and Rapido Rivers, the Gustav Line was an even more formidable barrier

than the Winter Line. Unless some strategy could be devised to turn the

defenses of the Gustav Line, Fifth Army faced another long and arduous

mountain campaign.

--2--

Plan for a New Offensive

The strategy decided upon by the Allied leaders, an amphibious

landing behind the Gustav Line, had been under consideration from the

time when German intentions in Italy became clear. By late October 1943

it was evident that the Germans intended to compel the Allied forces to

fight a slow costly battle up the peninsula. To meet this situation,

Allied staffs began to consider a plan for landing behind the enemy

lines, with the purpose of turning the German flank, gaining a passage

to the routes to Rome, and threatening the enemy lines of communication

and supply. On the Eighth Army front, a small-scale amphibious landing

at Termoli on 2-3 October 1943 furnished a pattern for such an attack.

On 8 November 1943 General Alexander ordered the Fifth Army to plan

an amphibious landing on the west coast. The target date was set at 20

December. The landing, to be made by a single division, was to be the

third phase of an over-all operation in Italy. In the first phase the

Eighth Army was to carry out an offensive which would put it astride

Highway No. 5, running from Pescara on the Adriatic coast through

Popoli

and Collarmele toward Rome. The second phase would be a Fifth Army

drive up the Liri and Sacco Valleys to capture Frosinone. Dependent on

the progress of the first two phases, a landing south of Rome directed

toward Colli Laziali (the Albanese Mountains) would be made, to link up

with the forces from the south. Because of tenacious German opposition

and difficult terrain, the Eighth and Fifth Armies in the Winter Line

campaign could not reach their assigned objectives. This situation,

together with the lack of available landing craft, made the plan for an

immediate amphibious end-run impracticable, and the project was

abandoned on 20 December 1943.

The slow progress of the Allied advance led to the revival of the

plan for an amphibious operation south of Rome along the lines

previously contemplated. At Tunis on Christmas Day the chief Allied

military leaders drafted new plans for an amphibious landing below Rome

with increased forces and the necessary shipping. Two divisions, plus

airborne troops and some armor-over twice the force originally

planned-were to make the initial assault between 20 and 31 January, but

as near 20 January as possible to allow a few days latitude if bad

weather should force postponement. The amphibious operation was again

to

be coordinated with a drive from the south, which would begin earlier.

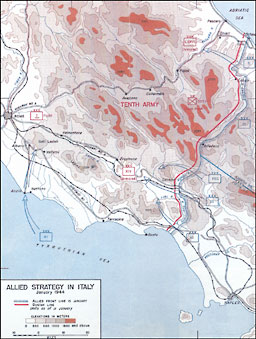

Map No. 2

Allied Strategy in Italy, January 1944

Main Fifth Army, reinforced by two fresh divisions from the

quiescent Eighth Army front, was to strike at the German Tenth Army

across the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers, breach the Gustav Line, and

drive up the Liri Valley. This offensive was planned in sufficient

strength to draw in most of the available German reserves. While the

enemy was fully occupied in defending the Gustav Line, the surprise

landing would be made in his rear at the twin resort towns of Anzio and

Nettuno, about thirty miles south of Rome. Once established, the

assault

force was to thrust inland toward the volcanic heights of Colli

Laziali. The capture of Colli Laziali would block vital enemy supply

routes and threaten to cut off the German troops holding the Gustav

Line. The Allied leaders believed that the Germans lacked sufficient

strength to meet attacks on two fronts and that they would be forced to

rush troops northward to meet the grave threat to their rear. Thus

weakened, the Germans could be forced to withdraw up the Liri Valley

from their Gustav Line positions. Eighth Army, though depleted of two

divisions which were to go to the Fifth Army front, was to make a show

of force along its front in order to contain the maximum number of

enemy

forces. If possible, Eighth Army would reach Highway No. 5 and develop

a

threat toward Rome through Popoli by 20 January. Main Fifth Army was to

follow up the anticipated enemy withdrawal as quickly as possible, link

up with the beachhead force, and drive on Rome.

The area chosen for the amphibious landing was a stretch of the

narrow Roman coastal plain extending north from Terracina across the

Tiber River. (Map

No. 3.)

Southeast of Anzio this plain

--3--

is covered by the famous Pontine Marshes; northwest toward the

Tiber

it is a region of rolling, often wooded, farm country. The 3,100-foot

hill mass of Colli Laziali lies about twenty miles inland from Anzio

and

guards the southern approaches to Rome.

(Map No. 21.)

Highway No. 7 skirts the west side of Colli Laziali; on

the southeast the mountains fall away into the low Velletri Gap leading

inland toward Highway No. 6 at Valmontone. The main west-coast railways

parallel these highways. On the east side of the Velletri Gap rise the

peaks of the Lepini Mountains which stretch along the inner edge of the

Pontine Marshes toward Terracina.

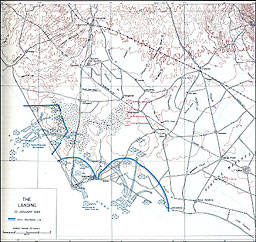

Map No. 3

The Landing, 22 January 1944

An area roughly seven miles deep by fifteen miles wide around Anzio

was to form the initial Allied beachhead.Its 26-mile perimeter was

considered the maximum which

could be held by the initial assault force and yet include the best

natural features for defense, In the sector northwest of Anzio the

beachhead was bounded by the Moletta River, Here the low coastal plain

was cut up by a series of rough-hewn stream gullies, the largest of

them

formed by the Moletta and the Incastro Rivers running southwest from

the higher ground inland toward the sea. These gullies, though their

small streams were easily fordable, were often fifty feet deep and

offered difficult obstacles to armor. In the central beachhead sector,

east of the first overpass on the Anzio-Albano road, the line ran 6,000

yards across a broad stretch of almost level open fields to meet the

west branch

LITTORIA AND THE RIGHT FLANK of the beachhead, viewed from

the

air. The Mussolini Canal flows from right to left across the terrain

shown in this photo, about one-third of the distance between Littoria

and Anzio. The Factory (Aprilia) was very similar in structure, and

built about the same time as Littoria.

--4--

of the Mussolini Canal below the village of Padiglione. This

stretch

of open country leading inland along the Albano road formed the best

avenue of approach into or out of the beachhead and was to be the scene

of major Allied and German attacks.

Between Cisterna and Littoria the plain merged with the northern

edge of the Pontine Marshes, a low, flat region of irrigated fields

interlaced with an intricate network of drainage ditches. The treeless,

level expanse offered scant cover for troops, and during the rainy

season the fields were impassable to most heavy equipment. From

Padiglione east the entire right flank of the initial beachhead line

was

protected by the Mussolini Canal, which drains the northern edge of the

Pontine Marshes, The line ran east along the west branch of the canal

to its intersection with the main branch and from there down the main

branch to the sea. The canal and the Pontine Marshes made the beachhead

right flank facing Littoria a poor avenue of attack; this flank could

be held with a minimum of forces.

Most of the beachhead area was within an elaborate reclamation and

resettlement project. The low, swampy, malarial bogland of the Pontine

Marshes had been converted into an area of cultivated fields, carefully

drained and irrigated by an extensive series of canals and pumping

stations. Only in the area immediately north of Anzio and Nettuno had

the scrub timber, bog, and rotting grazing land been left untouched. At

regular intervals along the network of paved and gravel roads

crisscrossing the farmlands were the standardized 2-story podere,

or farmhouses, built for the new settlers. Such places as the new

community center of Aprilia, called the "Factory" by Allied troops, and

the provincial capital of Littoria, were modernistic model towns. The

twin towns of Anzio (ancient Antium) and Nettuno in the center of the

beachhead were popular seaside resorts before the war.

The plan for the landing was called SHINGLE.

Originally conceived as

a subsidiary operation on the left flank of an advancing Fifth Army, it

developed, when main Fifth Army failed to break the

MAJ. GEN. JOHN P. LUCAS

Commanding General, VI Corps

mountain defenses in the south, into a major operation far in the

enemy rear. U.S. VI Corps, selected by General Clark to make the

amphibious landing, employed British as well as American forces under

the command of Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas. The assault force was to be

dispatched from Naples, and was to consist of the U.S. 3d Division,

veteran of landings in Sicily and North Africa, the British 1 Division

from the Eighth Army front, the 46 Royal Tank Regiment, the 751st Tank

Battalion, the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the 504th Parachute

Infantry Regiment, Commandos, Rangers, and other supporting troops.

This

force was the largest that could be lifted by the limited Dumber of

landing craft available. It was estimated that the turnaround would

require three days. As soon as the convoy returned to Naples, the U.S.

45th Division and the U. S. 1st Armored Division (less Combat Command

B), were sent as reinforcements.

The final plans for SHINGLE were completed and

approved on 12

January. D Day was set for

--5--

22 January; at H Hour (0200), VI Corps was to land over the

beaches

near Anzio and Nettuno in three simultaneous assaults. On the right,

the

3d Division, under Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., would land three

regiments in assault over X-Ray Red and Green Beaches, two miles below

Nettuno.2

In the center, the

6615th Ranger Force (Provisional) of three battalions, the 83d Chemical

Battalion, and the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion would come in

over

Yellow Beach, a small beach adjacent to Anzio harbor, with the mission

of

seizing the port and clearing out any coastal defense batteries there.

On

Peter Beach, six miles northwest of Anzio, the 2 Brigade Group of the

British

1 Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. W. R. C. Penney, would make the

assault; the 2 Special Service Brigade of 9 and 43 Commandos would land

with it and strike east to establish a road block on the main road

leading from Anzio to Campoleone and Albano. All these forces would

link

up to seize and consolidate a beachhead centering on the port of Anzio.

(Map No. 3.)

The assault plan assumed the possibility of initial heavy resistance

on the beaches, and the certainty of heavy counterattacks once the

enemy

was fully aware of the extent of the landing. Consequently, VI Corps

held out a strong reserve and placed great emphasis on digging in early

at initial objectives to repel armored counterattacks. The bulk of the

1

Division, with the 46 Royal Tank Regiment, the 24 Field Regiment, and

the So Medium Regiment attached, was to remain on shipboard as a

floating reserve. The 504th Parachute Infantry would land behind the 3d

Division and also assemble in Corps reserve. Up to a few days before

the

landing, it had been intended to drop the paratroopers behind the

beaches. This drop was called off because its objective was about the

same as that of the 1 Division, and because dropping before H Hour

might

prematurely reveal the main assault. A drop at H Hour itself might

incur the danger of being fired on by Allied artillery if enemy planes

should attack at the same time.

The Allied High Command expected that a landing in strength to the

rear of XIV Panzer Corps, opposing main Fifth Army on the

Cassino front, would be considered an emergency to be met by all the

resources of the German High Command in Italy. From the latest

intelligence available on enemy troops in the Rome area, Army G-2

estimated that VI Corps could expect an initial D Day resistance from

one division assigned to coast watching' four parachute battalions from

Rome, a tank and an antitank battalion, and miscellaneous coast defense

personnel, totaling 14,300 men. By D plus 1, another division, an SS

infantry regiment from north of Rome, a regimental combat team from XIV

Panzer Corps reserve, and perhaps elements of the Hermann

Goering Panzer Division could arrive. By D plus 2 or 3 the enemy

might have appreciated that the Allies had weakened the Eighth Army

front; if so, he could bring the 26th Panzer Division from that

sector to produce a total build-up of 31,000 men. If the Fifth Army

attack in the south were sufficiently powerful and sustained, it should

pin down all enemy reserves in that area. G-2 did not believe that the

Germans could bring down reinforcements quickly from northern Italy,

especially in the face of overwhelming Allied air superiority. Probable

build-up from north of Florence was estimated to be not more than two

divisions by D plus 16. The final summary by G-2, Fifth Army, on 16

January pointed out the increasing attrition of enemy troops:

Within the last few days there have been increasing

indications that enemy strength on the Fifth Army front is ebbing, due

to casualties, exhaustion, and possibly lowering of morale. One of the

causes of this condition, no doubt, has been the recent, continuous

Allied attacks. From this it can be deduced that he has no fresh

reserves and very few tired ones. His entire strength will probably be

needed to defend his organized defensive positions.

In view of the weakening of enemy strength on the front as

indicated above, it would appear doubtful if the enemy can hold the

organized defensive line through

--6--

PRELOADED SUPPLY TRUCKS AND DUKW's at Naples on 18 January

are loaded aboard LST's. This novel supply method was getting its first

Mediterranean battle test in the Anzio beachhead operation.

Cassino against a coordinated army attack. Since this

attack is to be launched before Shingle, it is considered likely that

this additional threat w ill cause him to withdraw from his defensive

position once he has appreciated the magnitude of that operation.

Whatever the enemy resistance and coast defenses might be, two natural

obstacles, bad weather and poor beaches, made a landing at Anzio in

January extremely hazardous. The winter rainy season was the worst time

of year to launch an amphibious assault. Rain, low clouds, and high

seas

promised to complicate the problem of supply over the beaches and to

hamper air support. The beaches themselves, much shallower than those

at Salerno, had the added disadvantage of two offshore sandbars. The

Navy estimated that only smaller craft such as LCVP's, LCA's, and

DUKW's could be landed with any reasonable

--7--

TROOPS FILING ABOARD AT NAPLES for the invasion were in a

happy

frame of mind when this picture was taken. A part of the 6615th Ranger

Force (Provisional), they were transported to Anzio aboard the stubby

LCI's shown in the background.

hope of success.3

These risks had to be accepted, although

special precautions could be taken to minimize their effect. Since the

weather promised only two good days out of seven, the assault convoy

was

to be combat-loaded for complete discharge within two days; to permit

larger craft to unload over the shallow beaches, pontons were to be

carried to serve as mobile piers; and to decrease the turnaround time

of

craft, the novel method of loading LST's with preloaded supply trucks

was to be used for the first time in the Mediterranean Theater. The

trucks were to load at Naples, drive onto the LST's, and drive off

again at Anzio. It was hoped that the small port of Anzio could be

captured before the enemy had time to demolish it. Its capture intact

would help to ease the grave problem of supply over open and exposed

beaches.

To protect the establishment of the beachhead an elaborate air

program in two phases was projected. Prior to D Day the Tactical Air

Force would bomb enemy airfields to knock out the German Air Force, and

would seek to cut communications between Rome and the north which enemy

reinforcements might use. The Strategic Air Force would assist in these

tasks. Then, from D Day on, every effort would be made to isolate the

beachhead from enemy forces by maintaining air superiority over the

beachhead, bombing bridges and road transport, and attacking enemy

columns or troop concentrations within striking distance.

--8--

For this program much of the strength of the Tactical Air Force

would be available, and assistance from other Allied air power in the

Mediterranean Theater would be on call. Support would be drawn from

some

2,600 Allied aircraft in Italy, Corsica, and Sardinia, representing an

overwhelming superiority over available German air power. XII Air

Support Command, under Maj. Gen. E. J. House, reinforced by two groups

from the Desert Air Force, would provide direct air support, while the

Tactical Bomber Force flew heavier missions. The Coastal Air Force

would give day and night fighter cover to the mounting area at Naples

and halfway up the convoy route. From here on the 64th Fighter Wing

would cover the battle area. A total of 60 squadrons (23½

fighter, 6 fighter-bomber, 4 light bomber, 24 medium bomber, and

2½ reconnaissance) would directly support the ground effort.

Enemy air power was not considered a major threat. By early January

almost the entire long-range bomber force of the Second German Air

Force, under General Baron von Richthofen, had disappeared from

Italian fields. it was believed that Allied attacks on enemy bases

would reduce the remaining German air strength by 60 percent, It was

not considered likely that the German Air Force would reinforce its

units in Italy to meet SHINGLE, so the enemy air

effort, never strong,

should gradually diminish.

Rear Admiral F. J. Lowry, USN, commander of Task Force 81, was

charged with the responsibility of mounting, embarking, and landing the

ground forces and with the subsequent support of this force until it

was

firmly established ashore. His assault convoy numbered 2 command ships,

4 Liberties, 8 LSI's, 84 LST's, 96 LCI's, and 50 LCT's, escorted by

cruisers, destroyers, and a host of lesser craft. It was divided into

two groups, Task Force X-Ray under Admiral Lowry to lift the American

troops, and Task Force Peter under Adm. T. H. Troubridge, RN, for

British troops.4

Since only sixteen 6-davit LST's were available, the eight LSI's had

been assigned to provide additional assault craft. Even with this

addition, LCI's would have to be used for follow-up waves over X-Ray

Beach. Peter Beach was so shallow that only light assault craft could

be

used.

Task Force X-Ray was further divided into several functional groups:

a control group of two flagships; a sweeper group to clear a mine-free

channel; and an escort group for antiaircraft and submarine protection.

A beach identification group was designated to precede the assault

craft, to locate the beaches accurately, and mark them with colored

lights. Then three craft groups would land the assault waves. Following

the first wave, the 1st Naval Beach Battalion would improve the marking

of beach approaches and control boat traffic. A salvage group was

assigned to lay ponton causeways after daylight for unloading heavier

craft. Back at Naples a loading control group would handle berthing and

loading of craft.

To gain surprise no preliminary naval bombardment of the beaches was

ordered, except a short intense rocket barrage at H minus 10 to H minus

5 minutes by three LCT(R)'s. An important assignment, however, was

given

to a naval task force which was to deliver a feint at H Hour of D Day

by

bombarding Civitavecchia, north of Rome, and by carrying out dummy

landings.

--9--

The Germans foresaw the possibility of an Allied landing behind

the

Gustav Line, and strengthened the coastal positions that were in the

most likely invasion areas as best they could with the limited number

of

troops at their disposal. Since it considered the number of German

troops in Italy barely sufficient to hold the southern front and

strengthen the rear areas, the German High Command in December 1943

worked out an elaborate plan to reinforce German troops in Italy with

units from France, Germany, and Yugoslavia in the event of an Allied

landing. Thus it was that while the Germans realized that they did not

have available sufficient forces to prevent an Allied landing behind

the

Gustav Line, they believed that they could contain and then destroy it

by hurrying reinforcements into Italy to meet the emergency. Their

plans did not contemplate the withdrawal of any substantial number of

troops from the southern front to meet such a threat to their rear.

The bitter and continuous struggle along the southern front from

November 1943 into January 1944 forced the enemy to commit all of his

divisions that were fit for combat to stop the Allied offensive at the

Gustav Line. A lull in the fighting in early January permitted the

strengthening of forces in the Rome area to resist an invasion. Under

the command of I Parachute Corps, the 29th and

--10--

THE ANZIO LANDING was virtually unopposed. These

scenes,

photographed at Yellow Beach soon after down on 22 January, show troops

of the 3d Division (above) as they waded the last few yards to shore

and

(below) a line of vehicles moving inland. White tape indicates boundary

of the path to which vehicles were confined by soft ground in the area.

90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions were assigned to the Rome

coastal sector; the Herman Goering Panzer Division was held as

a

mobile reserve between Rome and the southern front. But when the

American Fifth Army attacked across the Garigliano on 18 January, the

Germans rushed the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions

southward. On the eve of the Anzio landing, the Germans had almost

denuded the Rome area of combat troops in order to stem the Allied

drive

in the south. They had observed the regrouping of Allied troops and

Allied naval preparations in the Naples area; and they believed that

the Allies had sufficient strength both to maintain the offensive along

the main fighting front and to attempt a landing in the Rome area. But

they hoped to delay such an invasion by counterattacking in the south;

then, after stopping the Allies on the Garigliano, they would draw back

enough troops to check a landing.

The Assault

In early January, VI Corps troops assembled in the Naples area to

embark on a short but strenuous amphibious training program. Night

operations and physical conditioning through speed marches were

stressed. Infantry battalions practiced special beach assault tactics,

landings under simulated

--11

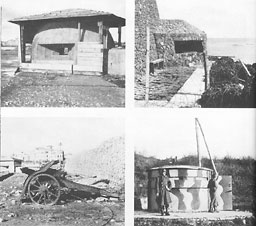

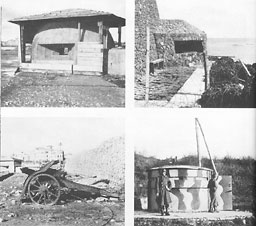

ENEMY COASTAL DEFENSES were sparse and mostly unmanned.

These

four photos, all taken in the Nettuno area, show the type of defenses

the Germans had set up. The cannon is an obsolete model.

fire, removing mine fields and barbed wire, and knocking out

pillboxes on the beach. Artillerymen learned the knack of loading and

unloading DUKW-borne 105-mm. howitzers. Assault landings were practiced

and repracticed, first from mock-ups on dry land and then in battalion

and regimental landing exercises with craft provided by the Navy. The

program culminated in WEBFOOT, a Corps landing

exercise lasting from 17

to 19 January on the beaches south of Salerno.5

As D Day approached, massed squadrons of medium and heavy bombers

roared out toward

--12--

northern Italy to strike the first blow in the new offensive.

Their

role was to choke off the vulnerable Italian rail and highway routes

down which enemy supplies and reinforcements could flow toward the

beachhead and the southern front. Shifting their weight from one main

line to another, Fortresses, Liberators, Mitchells, Marauders, and

Wellingtons hammered at key bridges and railroad yards from Rome north

to the Brenner Pass. Closer to the front, fighters and light bombers

strafed and bombed transport on the rail and highway nets. Finally, a

few days before the landing, heavy bombers flew missions against key

airfields in Italy and southern France to forestall any interference

from the Luftwaffe with the Anzio assault.

While the Anzio landing was stilt in preparation, main Fifth Army

began its southern drive. At dawn on 12 January, troops of the French

Expeditionary Corps surged forward in the mountains above Cassino.

While

the French sought to turn the German left flank above Cassino, the

British 10 Corps struck across the lower Garigliano to pierce the other

flank of the Gustav Line. In spite of successive assaults neither the

British nor the French were able to break through the rock-ribbed wall

of German mountain defenses. In the center, on 20 January, the U.S. II

Corps attacked in an effort to cross the Rapido and secure a

bridgehead. After gaining a precarious foothold in two days of bitter

fighting, heavy losses forced it to withdraw. By 22 January, D Day for

the Anzio landing, the attack on the Gustav Line had bogged down in the

midst of savage German counterattacks. Although Fifth Army had not

succeeded in driving up the Liri Valley, the battle for Cassino

continued

and the Germans had been forced to commit most of Tenth Army's

reserves. High hopes were still held that the Anzio landing would break

the stalemate in the Liri Valley.

During the third week in January, Naples and its satellite ports

were the scene of feverish activity as troops and supplies were loaded

on a convoy of more than 250 ships and craft. Long lines of

waterproofed

vehicles rolled down to the docks and troops filed aboard the waiting

ships. As dawn colored the hills above the Bay of Naples on 21 January,

the first ships slipped their hawsers and the convoy sailed.

It had been impossible to conceal craft concentrations in the Naples

area, but elaborate efforts were made to deceive the enemy as to the

time and place of the assault, which might fall anywhere from Gaeta to

Leghorn. The convoy plowed north from Naples at a steady 5-knot pace,

swinging wide on a roundabout course to deceive the enemy as to its

destination and to avoid mine fields. Allied air raids, however, had

temporarily knocked out the German reconnaissance base at Perugia, and

not an enemy plane was sighted in the sunlit sky. Mine sweepers cleared

a channel ahead, destroyers and cruisers clung to the flanks to ward

LT. GEN. MARK W. CLARK, Commanding General of the Fifth

Army,

arriving at the beachhead on D Day morning in a Navy PT boat. He is

shown reading radio dispatches on the battle's progress with a Fifth

Army Staff officer.

--13--

A DESTROYED MUSSOLINI CANAL BRIDGE near Borgo Sabotino, part

of

the reconnaissance effort on the right flank on D Day. Photo, taken

later, shows a treadway bridge over the canal, concrete road blocks

(German) on the far side, and a trench system dug by American forces.

off U-boats, and an air umbrella of fighters crisscrossed

constantly. Actually, these elaborate precautions were hardly

necessary,

for the enemy air reconnaissance failed to observe either the

embarkation at Naples or the approach of VI Corps to Anzio, Aboard the

convoy men tolled about the decks, sleeping or sunbathing, checking

equipment, or excitedly discussing what they would find. As night felt

and darkness cloaked the convoy's movements, it swung sharply in toward

Anzio.

At five minutes past midnight on 22 January, in the murky blackness

off Cape Anzio, the assault convoy dropped anchor and rode easily on a

calm Mediterranean Sea. There was a murmur of subdued activity as

officers gave last-minute instructions, men clambered into stubby

assault craft, and davits swung out and lowered them to the sea. Patrol

boats wove in and out of the milling craft herding them into formation,

and then led the first waves away into the moonless night.

To gain surprise the guns of the escorting warships kept silent.

Then, just ten minutes before H Hour (0200), a short, terrific rocket

bombardment from two British LCT(R)'s burst with a deafening roar along

the beach. These newly developed rocket craft, each carrying 798 5-inch

rockets, were employed to disorganize any possible enemy ambush,

explode

mine fields along the beach, and destroy enemy beach defenses. But the

attackers saw no burst of answering fire; when the rocket ships ceased

firing, the shore again loomed dark and silent ahead.

As the first wave of craft hit the beach and men rushed for the

cover of the dunes behind, there was no enemy to greet them. Pushing

rapidly inland the astonished troops soon realized that the highly

unexpected had happened. They had caught the enemy completely off

guard.

Although the Germans knew an amphibious landing was impending, they

believed that it would not occur until somewhat later. The two

divisions that had been assigned to guard this coast had been sent to

the southern front only three days before, and the coastal sector and

area south of Rome were held by only skeleton forces. Consequently,

except for a few small coast artillery and antiaircraft detachments,

the

only immediate resistance to the Anzio landing came from scattered

elements of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. Only three

engineer companies and the 2d Battalion, 71st Panzer Grenadier

Regiment, had been left to guard the coast from the mouth of the

Tiber River through Anzio to the Mussolini Canal; one 9-mile stretch of

the coast was occupied by a single company. Furthermore, the troops in

the Anzio area had not been warned that an Allied landing was imminent.

The coastal defenses were limited to scattered mine fields along Peter

Beach used by the British 1 Division; some pillboxes, most of which

were

not even manned; and scattered artillery pieces-a few 88's and several

old Italian,

--14--

French, and Yugoslav pieces-most of which were not even fired

against the attackers.

Aided by a calm sea and the virtual absence of opposition, the

invaders quickly established themselves on shore.

(Map No. 3.)

On the right, the 3d Division swept in over the beaches

east of Nettuno. Brushing aside a few dazed enemy patrols, they pushed

rapidly inland, established themselves on the initial phase line, and

dug in to repel any counterattack. General Clark, accompanied by Brig.

Gen. Donald W. Brann and other members of the Fifth Army Staff, arrived

at the beachhead in a Navy PT boat, transferred to a DUKW, and landed

at 1000. Motorized patrols of the 3d Reconnaissance and Provisional

Reconnaissance Troops forged ahead to seize and blow the bridges over

the Mussolini Canal which ran along the right flank. Only at the

southernmost bridge did they meet any Germans. Here they knocked out

three armored cars with bazookas,

ENGINEERS CLEARING DEMOLITION CHARGES IN ANZIO on

D Day. The Germans failed to carry out their plans to destroy the port.

Explosives, such as these men of the 36th Engineers are seen removing

had been set so that buildings would topple into the streets, and thus

hinder use of port facilities.

--15--

AN AIR ATTACK ON CISTERNA by medium bombers shows smoke and

dust

rising from bomb hits on enemy installations and the railroad just

south

of the town. Note the narrow, winding Cisterna Creek directly below

plane.

--16--

killing or capturing eleven of the enemy patrol.

The Ranger Force landed over the small beach just to the right of

Anzio harbor and swiftly seized the port. The Rangers scrambled up the

steep bluff, topped with pink and white villas overlooking the beach,

and spread through the streets of the town, rounding up a few

bewildered

defenders. The Germans had had no time to demolish the port facilities.

Except for a gap in the mole and some battered buildings along the

waterfront (damage caused by Allied bombers), the only obstacles were a

few small vessels sunk in the harbor. Later in the morning the 509th

Parachute Infantry Battalion advanced east along the shore road and by

1015 occupied Nettuno. Northwest of Anzio the landing of the British 1

Division was equally unopposed, although delayed by poor beach

conditions. By noon of D Day VI Corps had reached all its preliminary

objectives ashore.

In support of the landing, Allied fighter and bomber squadrons flew

more than 1,200 sorties on D Day. Medium and heavy bombers blasted key

bridges and such road junctions as Cisterna and Velletri in an attempt

to block the main roads leading toward the Anzio area. Fighter-bombers,

fighters, and night intruders ranged these highways, bombing and

strafing the enemy traffic beginning to surge toward the beachhead.

Other fighters gave continuous air cover to the landing force. Enemy

air

attacks were comparatively slight on D Day, totaling 140 sorties, but

increased in intensity on 23 January.

PUTTING DOWN ROAD MATTING at the beach exits was one of the

problems confronting the engineers after the landings. Many heavy

vehicles and the rapid supply build-up made the construction of a

number

of such roadways necessary.

--17--

Behind the assault troops pushing inland, unloading of the initial

convoy proceeded at a rapid pace. Engineers swiftly cleared the

scattered mine fields and bulldozed exit roads across the dunes; but

the

clay soil between the beaches and the main road soon became so badly

rutted that matting, corduroy, and rock had to be laid down to make the

area passable. DUKW's and small craft scurried back and forth across

the calm waters of Nettuno Bay, busily unloading the larger craft which

were unable to approach the shallow beach. In spite of sporadic

shelling after daylight from a few long-range German batteries inland

and three small hit-and-run raids by Luftwaffe fighter-bombers, the

540th Engineers quickly moved streams of men and supplies across the

beach. A mine sweeper hit a mine and one LCI was sunk by the bombs, but

this was the only major damage. The 36th Engineers began clearing the

debris from the port of Anzio; the Navy hauled away the sunken vessels.

By early afternoon the port was ready to handle LST's and other craft.

When the British beach northwest of Anzio proved to be too shallow for

effective use, it was closed and British unloading switched to the

newly opened port. By midnight of D Day some 36,000 men, 3,200

vehicles, and large quantities of supplies were ashore, roughly 90

percent of the equipment and personnel of the assault convoy.

Casualties for D Day were light. Thirteen killed, ninety-seven

wounded, and forty-four captured or missing were reported to VI Corps,

Two hundred and twenty-seven prisoners were taken. Against negligible

opposition VI Corps had reached its preliminary objectives and captured

almost intact the port of Anzio, which was to be the key channel for

supplies.

Expanding the Beachhead

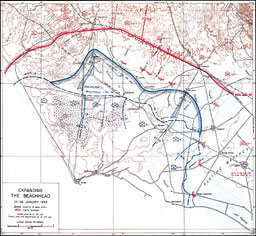

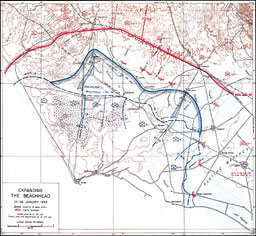

Map No. 4

Expanding the Beachhead, 24-28 January 1944

Having reached its preliminary objectives by noon of D Day, VI Corps

moved forward to occupy the ground within the planned initial beachhead

line. The British 1 Division advanced from its beaches on the left

toward the Moletta River and gained control of seven miles of the

Albano

road. In the 3d Division sector the advance resolved itself into a

series of actions to gain the bridges over the Mussolini Canal, vital

to the defense of the right side of the beachhead.

By the evening of D Day, advance guards of the 30th Infantry and the

3d Reconnaissance Troop

--18--

UNLOADING AT ANZIO'S DOCKS began D Day afternoon when

the engineers

cleared the harbor. LST's (above) were able to nose directly into the

docks and soon afterward British troops (below) were moving through the

battered port instead of over the shallow northern beaches.

had seized all of the bridges across the canal. The enemy regained

most of the bridges that night in attacks by aggressive, tank-supported

attacks launched by elements of the Hermann Goering Panzer Division.

The next morning Lt. Col. Lionel C. McGarr, commander of the 30th

Infantry, brought up the remainder of his regiment, supported by tanks

and tank destroyers; in sharp fighting it drove the enemy back across

the bridges along the west branch. The Germans counterattacked with

three tanks and a half-track to regain the bridge on the Cisterna road

north of Conca, but the 30th Infantry's supporting armor drove them

off.

On the right of the 30th Infantry, the 504th Parachute Infantry, which

had come ashore in Corps reserve, on 24 January relieved the 3d

Reconnaissance Troop along the main canal and retook the other lost

bridges.

--19--

By 24 January the 3d Division had occupied the right sector of the

initial beachhead along the Mussolini Canal. The 504th Parachute

Infantry held the right flank along the main canal; in the center the

15th Infantry, and on its left the 30th Infantry, faced Cisterna along

the west branch. Ranger Force relieved all but the 3d Battalion, 7th

Infantry, on the division left in the quiet central beachhead sector.

Meanwhile the 2 Brigade of the 1 Division, under the command of Brig.

E.

E. J. Moore, rounded out its sector of the beachhead by advancing to

the Moletta River line. The remainder of the division was held in Corps

reserve in anticipation of an enemy counterattack. In two days VI Corps

had secured a beachhead seven miles deep against only scattered

opposition.

Although the Anzio landing and initial Allied build-up were

virtually unopposed by German land forces, the enemy reacted swiftly to

meet the emergency. Headquarters of Army Group C immediately

alerted elements of the 4th Parachute and Hermann Goering

Panzer Divisions south of Rome and ordered them to defend the roads

leading from Anzio toward Colli Laziali. At 0600 on 22 January it set

in

motion the prearranged plan to rush troops from outside of Italy to

stem the Allied invasion. Two divisions and many lesser units started

at

once from France, Yugoslavia, and Germany itself. Three divisions of

the Fourteenth Army in northern Italy were alerted and left for

the Rome area on 22-23 January. To command the defense, I Parachute

Corps reestablished its headquarters in the area below Rome at 1700

on 22 January. All available reserves from the southern front or on

their way to it were rushed toward Anzio; these included the 3d

Panzer Grenadier and 71st Infantry Divisions, and the bulk

of

the Hermann Goering Panzer Division. While these forces were

assembling, the German Air Force bombed the beachhead area and its

supporting naval craft in order to delay an Allied advance inland. For

the first two days, the German defenders believed that

ADVANCING TOWARD THE MUSSOLINI CANAL, elements

Of the 504th Parachute Infantry on D Plus 2 moved in small groups and

then only when protected by smoke screens. The canal is just beyond the

smoke on the horizon, about 1,000 yards from the building in the

foreground.

--20--

they were too weak to stop an Allied advance against Colli

Laziali;

but from the evening of 24 January they were confident that they could

contain the beachhead forces and, as soon as they had substantially

completed their concentration, launch a counterattack that would wipe

out the Allied beachhead.

Army Group C on 24 January ordered the Fourteenth Army

to take over the command of the German operations before Anzio. When

the Fourteenth

Army, commanded by Gen. Eberhard von Mackensen, assumed control on

25 January, elements of eight German divisions were employed in the

defense line around the beachhead, and five more divisions with many

supporting units were on their way to the Anzio area. By 28 January, Fourteenth

Army had assigned command of the forces defending the eastern

sector

of the beachhead perimeter (before Cisterna) to the Hermann Goering

Panzer Division; of the central sector (before Campoleone) to the 3d

Panzer Grenadier Division; and of the western sector (behind the

Moletta River) to the 65th Infantry Division. Behind this

perimeter other units were grouped for counterattack. A gap of four or

five miles separated the German main line of resistance from the main

beachhead line occupied by the Allied VI Corps by 24 January.

The reaction of enemy forces gave no impetus to main Fifth Army's

drive and made the prospect of linking the southern force with the

beachhead remote. Also, if VI Corps extended itself too far inland

toward Colli Laziali, its main objective, it would risk being cut off

by

a sudden German counterthrust. Before the end of D Day the Germans were

estimated to have 20,000 troops in areas from which they could drive

rapidly toward the beachhead. With the advantage of good

communications, roads, and railroads, and in spite of Allied air

interdiction, they had doubled that figure by D plus 2, and continued

to

increase it to more than 70,000 by D plus 7. This growing strength

indicated that VI Corps would have to prepare to meet an enemy thrust

calculated to drive the Allied forces back into the sea.

VI Corps consequently consolidated its positions during the period

24-29 January. White awaiting reinforcements, Allied troops probed

along

the two main axes of advance toward the intermediate objectives of

Cisterna and Campoleone, which would serve as strategic jump-off points

for the advance an Colli Laziali. On the right the 3d Division moved up

the roads leading across the Mussolini Canal toward Cisterna; on the

left the British pushed up the Albano road toward

Campoleone.6

(Map No. 4.)

On the afternoon of 24 January, four companies of the 15th and 30th

Infantry made a preliminary reconnaissance in force toward Cisterna,

but

they were unable to make much headway against strong enemy mobile

elements, General Truscott then ordered an advance in greater force at

dawn on 25 January up the two main roads leading across the muddy

fields

toward the town. The 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, advanced up the

left-hand or Campomorto-Cisterna road, while the 2d Battalion, 15th

Infantry, took the right up the Conca-Cisterna road.

About two miles beyond the canal the 30th Infantry was halted by a

company of the Hermann Goering Panzer Division, intrenched

around the road junction halfway to Ponte Rotto. On the right of the

30th Infantry, the 2d Battalion, 15th Infantry, gained one and one-half

miles up the Conca-Cisterna road before it was stopped by German

machine

gunners concealed within the farmhouses along the route. Tanks and tank

destroyers of the 751st Tank Battalion and the 601st Tank Destroyer

Battalion were brought up to reduce these strong points. Before the

armor could go into action German units infiltrated down a stream bed

forcing the outposts along the 2d Battalion's right flank to withdraw.

Company C, which was making a diversionary attack up a parallel road to

the right of the Conca-Cisterna road, bogged down before similar

resistance and four of its accompanying tanks were lost to an enemy

self-

--21--

propelled gun. With unexpected strength the veteran Hermann

Goering Panzer Division had blunted the spearheads of the 3d

Division

attack. Not having time to prepare fixed defenses, the Germans had

emplaced machine guns and antitank guns in every farmhouse along the

roads. These strong points had excellent interlocking fields of fire

across the gently rolling fields and were supported by roving tanks and

self-propelled guns. They had to be knocked out one by one by American

tanks and tank destroyers before the infantry could advance.

To assist the main effort, paratroopers of the 504th Parachute

Infantry made a diversionary attack across the main canal toward

Littoria. Advancing behind a heavy curtain of supporting fires,

augmented by the guns of the cruiser Brooklyn and two

destroyers,

they captured the villages of Borgo Sabotino, Borgo Piave, and Sessano

on the east side of the canal. Company D, however; was cut off beyond

Borgo Piave by a surprise counterthrust of five tanks and eight flakwagons

(self-propelled antiaircraft guns) of the Hermann Goering Panzer

Division. Company D lost heavily, though many of the men managed to

infiltrate back. That night the 504th Parachute Infantry, leaving

behind strong combat patrols, withdrew from its exposed positions.

The 3d Division resumed its push toward Cisterna the next morning,

26 January. In the 30th Infantry zone the 1st Battalion infiltrated

around the road junction below Ponto Rotto where it had been held up,

and forced the enemy to withdraw. That afternoon the 1st Battalion,

15th

Infantry thrust northeast up the right-hand road across the west branch

of the canal to establish a road block on the Cisterna-Littoria road.

In spite of seventy minutes of massed supporting fire from the 9th,

10th, and 39th Field Artillery Battalions, and neutralizing fire by

heavier guns, the Germans clung tenaciously to their positions. Behind

a similar elaborate artillery preparation, the 2d Battalion, 15th

Infantry, on 27 January pushed up the Conca-Cisterna road. At the same

time the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, continued its attack on the

right. It gained some ground but was unable to break

THE RIGHT FLANK AT THE MUSSOLINI CANAL was

covered by the 504th Parachute Infantry, dug in on the east bank. This

position was west of Littoria, toward which a diversionary attack was

launched in support of the 3d Division on 25 January.

--22--

ENEMY SHELLFIRE HITTING THE BEACHES did not halt the work of

DUKW's which carried supplies from Liberty ships offshore. This

sporadic

shelling was considered a nuisance, but caused only limited damage.

through to its objective. Rushing new units into the line piecemeal

as fast as they arrived, the Germans were making every effort to keep

the Americans from reaching Highway No. 7. In the attacks of 25-27

January the 3d Division reached positions one to two miles beyond the

west branch of the Mussolini Canal; it was still three miles from

Cisterna. It became evident that an effort greater than was immediately

possible would be necessary to reach the division's objective. General

Truscott therefore called a halt in the advance to regroup for a more

concentrated drive.

To parallel the drive of the 3d Division, the British 1 Division had

been ordered to move up the Albano road to Campoleone, to secure this

important road and railway junction as a jump-off point for a further

advance. With the arrival of the 179th Regimental Combat Team (45th

Division), VI Corps released from Corps reserve the 24 Guards Brigade

for this move. A strong mobile patrol up the road on 24 January

surprised an enemy outpost at Carroceto, and continued four miles

farther inland to a point north of Campoleone. To exploit this apparent

enemy weakness, General Penney on 25 January dispatched the 24 Guards

Brigade, with one squadron of the 46 Royal Tanks and one medium and two

field regiments of artillery in support, to take the Factory (Aprilia)

near Carroceto. The 3d Battalion, 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment

(3d

Panzer Grenadier Division),

--23--

however, had occupied the Factory the night before. The 1 Scots

Guards and 1 Irish Guards pushed through a hasty mine field across the

road, and the 5 Grenadier Guards then drove the enemy from the Factory,

capturing 111 prisoners. (Map No. 4)

The enemy, sensitive to the loss of this strong point,

counterattacked strongly the next morning. Twenty tanks and a battalion

of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment thrust at the 5 Grenadier

Guards in the Factory. Their main assault was repulsed, but they

continued to feel around the flanks until they were finally driven off

that afternoon. The Germans left behind four burning tanks, one

self-propelled gun, and forty-six more prisoners. By the morning of 28

January the 24 Guards Brigade had advanced one and one-half miles north

of the Factory. The 1 Division then paused to regroup for an attack on

Campoleone.

By 29 January, VI Corps had expanded its beachhead by the advances

of the 1 and 3d Division, but was still from two to four miles short of

its two intermediate objectives. It was clear that an attack in greater

strength would be necessary to continue the drive. The Corps paused to

regroup.

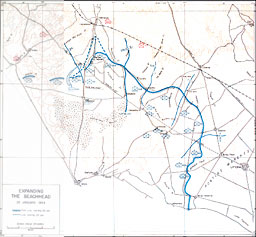

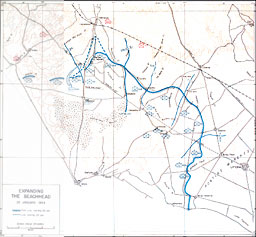

Map No. 5

Expanding the Beachhead, 29 January 1944

Behind the assault troops pushing inland, engineers and service

troops worked day and night to organize the beachhead and prepare a

firm

base for the main attack. Roads were repaired, dumps established, and a

beginning made on defenses to meet any future German counterthrusts.

The port, vital to the supply build-up and troop reinforcement, was

placed in such effective operation that by 1 February it could handle 8

LST's, 8 LCT's, and 5 LCI's simultaneously. Liberty ships, however,

were unable to enter the shallow harbor and continued to be unloaded by

DUKW's and LCT's over X-Ray and Yellow Beaches. The weather during the

first week at Anzio turned out much better than anticipated and greatly

facilitated the stockage of supplies. The port was usable in all but

the worst weather, and only on two days during the first week, 24 and

26 January, was unloading over the beaches halted by high winds and

surf. A gale during the night of 26 January blew ashore all ponton

causeways and beached 12 LCT's, 1 LST, and 1 LCI. In spite of these

interruptions and enemy interference, 201 LST's and 7 Liberty ships had

been completely unloaded by 31 January. On the peak day of 29 January

6,350 tons were unloaded: 3,155 tons through the port, 1,935 over X-Ray

Beach, and 1,260 over Yellow Beach.

The beach and port areas, still within range of German artillery,

were vulnerable targets for increasing shelling. Long-range 88-mm. and

170-mm. batteries dropped their shells sporadically on ships off shore

and among troops working along the beach. Although this fire was a

nuisance to the troops and interfered with work, it caused only limited

damage in the early days. Floating mines continued to be a menace,

damaging a destroyer and a mine sweeper. On 24 January an LST carrying

Companies C and D, 83d Chemical Battalion, struck a mine. Most of the

men were transferred to an LCI alongside, which also hit a mine and

sank. Total casualties were 5 officers and 289 men.

Far more dangerous to beach and shipping were the constant Luftwaffe

raids. The German Air Force put up its biggest air effort since Sicily

in an attempt to cut off Allied supplies. Small flights of

fighter-bombers strafed and bombed the beach and port areas every few

hours. The most serious threat, however, was the raiding by medium

bomber squadrons hastily brought back from Greece and the torpedo and

glider bombers from airfields in southern France. Skimming in low at

dusk from the sea through the smoke and hail of ack-ack fire, they

released bombs, torpedoes, and radio-controlled glider bombs on the

crowded shipping in the harbor. In three major raids, on 23, 24, and 26

January, they sank a British destroyer and a hospital ship, damaged

another hospital ship, and beached a Liberty ship. The two heaviest

raids came at dusk and midnight on 29 January, when 110 Dornier 217's,

Junkers 88's, and Messerschmitt 210's sank a Liberty ship and the

British antiaircraft cruiser Spartan.

Stiffening air defenses took a heavy toll of the Luftwaffe raiders,

downing ninety-seven of them before 1 February. Initially Col. Edgar W.

King

--24--

ANTIAIRCRAFT GUNS AND BARRAGE BALLOONS appeared in

increasing

numbers as the German air raiders stepped up their attacks. The crew

above mans a 40-mm. Bofors gun. Shown below is one of the low-level

type

balloons designed to counter strafing attacks.

--25--

of the 68th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) and later

Brig.

Gen. Aaron A. Bradshaw, Jr., supervised the installation of increasing

numbers of 40-mm. and 90-mm. antiaircraft guns and established a

12,000-yard inner artillery zone around the vital beach and port areas.

Barrage balloons were raised to halt low-level bombing and smoke

screens

blanketed the port at dusk and on every red alert. The enemy's favorite

tactic was to sneak over at dusk, when Allied planes, which needed

daylight to take off, were returning to their 100-mile distant bases.

To combat these sneak raids the engineers renovated the old Italian

artillery school air strip at Nettuno. P-40's of the 307th Fighter

Squadron moved up to the beachhead to furnish "on the spot" cover, and

the Air Force increased its use of Beaufighter night patrols and

Spitfires trained for night fighting.

Good weather during most of the first week at Anzio and the aid

rendered by use of the port enabled the assault convoy to be unloaded

rapidly and turned around to bring up the follow-up force. The 45th

Division and the 1st Armored Division (less Combat Command B, which was

retained for possible employment at Cassino) had reached the beachhead

by 1 February. Essential Corps artillery, engineers, and signal troops

had also arrived.

Although the Germans in the Anzio area outnumbered VI Corps by 30

January, it was believed that their defenses had not progressed beyond

road blocks, hasty field fortifications, and mine fields along likely

avenues of approach. Allied patrols could still operate freely to

Highway No. 7 and Campoleone, The positions the enemy was constructing

along the railroad between Campoleone and Cisterna were believed to be

intended for delaying action, It was anticipated that his main stand

against an Allied advance would more likely be along the high ground

around Cori and Velletri.

In view of the rapidly increasing enemy build-up, General Lucas

decided to launch his drive toward Colli Laziali before his forces

might

be too far outnumbered. On 30 January the enemy forces in the beachhead

area were estimated to number 71,500; VI Corps had 61,332 troops ashore

on the same date. It was planned to resume the 3d Division push on

Cisterna on 29 January, but the attack was delayed one day to permit

the 1 Division and the 1st Armored Division to complete preparations

for a coordinated offensive. On 30 January all three divisions were to

attack.

The drive of VI Corps out of the Anzio beachhead was designed to

coincide with a renewed offensive on the southern front. On main Fifth

Army's front, II Corps was preparing to open its drive on Cassino on 1

February, with the 34th Division carrying the attack. The 10 Corps in

the Garigliano sector continued the consolidation of the bridgehead

which it had successfully established in an attack on 17-20 January. On

the Eighth Army front the Canadian 1 Division was to attack in the

coastal sector on 30 January.

The Germans originally planned to counterattack the Allied beachhead

in force on 28 January. But Allied bombings of roads and railways, and

a

desire to await the arrival of reinforcements from Germany, led to a

decision on 26 January to postpone the attack until 1 February. In

preparation, the enemy proceeded to arrange his infantry and artillery

into three combat groups. The principal assault was to be launched

southward along the Albano-Anzio road (with the main concentration on

either side of the Factory) by Combat Group Graeser, which

would

consist of seventeen infantry battalions heavily supported by

artillery. While the main effort was to be made in the center, the

Germans planned to launch simultaneous attacks all along the front on

the morning of D Day, 1 February; these were to be preceded by a

coordinated 10-minute artillery barrage. While the necessary

regroupings

were under way, Allied VI Corps launched its offensive on 30 January

forcing the Germans to postpone their attack until after the Allied

drive had been stopped.

--26--

Contents *

Previous Chapter (Foreword) *

Next Chapter (2)

Footnotes

1

An account of this operation is given in

Fifth Army at the Winter

Line

(American Forces in Action Series,

Military Intelligence Division, U.S. War Department), Washington, 1945.

2

Attached: 601st

Tank Destroyer Battalion; 751st Tank Battalion; 441st AAA Automatic

Weapons Battalion; Battery B,

36th Field Artillery Regiment (155-mm. gun); 69th Armored Field

Artillery Battalion

(105-mm. self-propelled howitzer); and 84th Chemical Battalion

(motorized).

3

The naval craft referred to by abbreviations in

this and subsequent chapters are identified as follows:

| DUKW |

-Amphibious Truck |

| LCA |

-Landing Craft, Assault |

|

LCI |

-Landing Craft, infantry |

| LCT |

-Landing Craft, Tank |

| LCT

(R) |

-Landing Craft, Tank (Rocket) |

| LCVP |

-Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel |

| LSI |

-Landing Ship, Infantry |

| LST |

-Landing Ship, Tank |

4

The naval craft were assigned as follows:

| Task Force "Peter" (British) |

Task Force "X-Ray" (American) |

| 1 Hq ship |

1 Hq ship |

| 4 cruisers |

1 cruiser |

| 8 Fleet destroyers |

8 destroyers |

| 6 Hunt destroyers |

2 destroyer escorts |

| 2 antiaircraft ships |

6 mine sweepers |

| 2 Dutch gunboats |

12 submarine chasers (173´) |

| 11 fleet mine sweepers |

20 submarine chasers (110´) |

| 6 small mine sweepers |

18 motor mine sweepers |

| 4 landing craft, gun |

6 repair ships |

| 4 landing craft, flak |

|

| 4 landing craft tank (rocket) |

|

5

During the WEBFOOT

exercise the 3d Division lost one battalion of field artillery due to

DUKW's swamping

when put into the sea too far off shore during bad weather. This

illustrates the absolute

necessity for proper loading and trained crews in the use of this type

of equipment. Very

few men were drowned, but the DUKW's and all equipment went to the

bottom. This battalion

was replaced by a battalion of the 45th Division before the 3d Division

sailed for Anzio.

6

Campoleone Station.

The town of Campoleone is about a mile and a quarter north. References

to Campoleone

throughout this study are to the railroad station, not to the town

proper.

Transcribed and formatted for HTML by David Newton for the

HyperWar Foundation