Conquest may be too slow as well as too rapid – a middle course adopted by the English – Proposal for expelling Janojee Bhonslay from Kuttack – Views of the Court of Directors on the East and West of India – Occupation of Rajamundree – Alliance with Nizam Ally – objects – Mahdoo Rao enters the Carnatic, levies tribute from Hyder, and returns to Poona – New treaty between Nizam Ally and the English – Rugonath Rao proceeds on an expedition into Hindoostan – Death of Mulhar Rao Holkar – his widow Aylah Bye appoints Tookajee Holkar to the command of her army – Rana of Gohud – his rise – rebellious proceedings – Rugonath Rao fails in an attempt to reduce him – accepts a tribute, and returns to Poona – jealousy and distrust towards his nephew – retires from Poona, and supported by Holkar, Janojee Bhonslay, and Dummajee Gaekwar, rebels against him – Curious anecdote of Mahdoo Rao – Rebellion crushed, and Rugonath Rao placed in confinement – Mahdoo Rao forms an alliance with Nizam Ally against Janojee – conceals his real design with great political artifice – effect on the English and Hyder – invades Berar – plunders Nagpoor – judicious conduct of Janojee – ravages the Peishwa’s territory – Mahdoo Rao is compelled to raise the siege of Chandah and return to oppose Janojee – Janojee avoids an action, and cuts off a part of the Peishwa’s baggage – treaty of Kunkapoor – The Peishwa sends an expedition to Hindoostan under Visajee Kuhn Beneewalla – anecdote relative to Mahadajee Sindia – Mahdoo Rao’s endeavours to improve the civil government – Ram Shastree – account of – anecdote – admirable character – The practice of forcing villagers to carry baggage abolished – Encroachments of Hyder – The Peishwa proceeds against him – reduces a large tract of territory – Anecdote of the rival Ghatgays at the storm of Mulwugul – obstinate defence of Nidjeeghul – operations continued – Mahdoo Rao

is compelled to leave the army from ill health – Trimbuck Rao Mama prosecutes the war – defeats Hyder, who loses the whole of his artillery, camp equipage, &c – Seringapatam besieged – peace concluded – motives and terms – Proceedings in Hindoostan – Affairs of the imperial court since the battle of Panniput – The emperor seeks and obtains the protection of the English – The East India Company appointed Dewan to the Nabob of Bengal – Affairs at Delhi – Visajee Kishen levies tribute from the Rajpoots – defeats the Jhats near Bhurtpoor – Nujeeb-ud-dowlah negotiates with the Mahrattas – reference to the Peishwa – overtures admitted – death of Nujeeb-ud-dowlah – The Mahrattas invade Rohilcund – The emperor quits the protection of the English, and is re-instated on his throne by the Mahrattas – The Mahrattas overrun the territory of Zabita Khan – Policy of Shujah-ud-dowlah in regard to the Rohillas – on receiving a subsidy, concludes a defensive alliance with them – Insolence and rapacity of the Mahratta Bramins – The emperor assisted by Nujeef Khan, determines to throw off their yoke – Death of Mahdoo Rao – his character – Account of his civil administration – general review of the interior management and state of the country and people, including the police – civil and criminal justice – finance – army

Whilst universally admitted that unwieldy dominion is the forerunner of certain decline, it is not always considered that, under some circumstances, conquest may be too slow, as well as too rapid. Illustrative of this observation, we have some striking examples connected with the history of Maharashtra, particularly in the decay of the Portuguese, and the rise of the Mahrattas. The middle course, as steered by the English, and the steady march of aggrandizement which they have hitherto pursued in the East, is to be ascribed to the remarkable men, who have, at various periods, directed their councils

and their armies; and to the caution of a body of merchants, who, though pleased at the gain, were appalled at the venture, and who feared the loss of all they had acquired by each succeeding contest into which they were plunged.

Lord Clive, who returned from England to assume the government of Bengal in May 1765, not only perceived that it was impossible for the English to recede, but was convinced that to advance was essential to their preservation. Of the three great powers, the Mahrattas, Nizam Ally, and Hyder, the first was considered the most formidable. As early as the end of the year 1761, immediately after the death of Ballajee Rao, when Mr. Vansittart was President of the Council in Bengal, it was intended to expel Janojee Bhonslay from Kuttack; and it was proposed, not only to the governments of Madras and Bombay, but to the Emperor of the Moghuls, to Sulabut Jung183 and Nizam Ally. Although the sister presidencies, for various sufficient reasons disapproved of the expedition, it was prevented, not seemingly on account of their disapproval, but at the request of the Nabob of Bengal.

The Court of Directors were desirous of seeing the Mahrattas checked in their progress, and would have beheld combinations of the other native powers against them with abundant satisfaction:

but they were apprehensive of the-consequences of granting a latitude to their own servants, or of being engaged as umpires or auxiliaries; and their instructions were designed to prevent their becoming involved in hostilities, especially as principals, in any case short of absolute defence. With these cautious views, however, they were anxious to attain two objects which they deemed of vital importance to their security; the first, of old standing, was one in which the Mahrattas were directly concerned, the possession of Salsette, Hog Island, and Caranja, in the neighbourhood of Bombay, which every year tended to render more important; the second, the accomplishment of which devolved more particularly on the presidency of Madras, was the occupation of the five districts formerly belonging to the French, on the eastern coast of the Peninsula, best known as the Northern Circars. With respect to the first, the Mahrattas, though but a few years before they scarcely regarded the English, were now too jealous of their aggrandizement, willingly to relinquish the islands alluded to; besides which, they attached peculiar value to these possessions, as the fruits of their success against an European nation. In regard to the second, Guntoor, one of the five districts in question, was appropriated as the Jagheer of Busalut Jung. Nizam Ally, having at one time offered to farm the remaining four to the Nabob of Arcot, it was hoped he might allow the Company to occupy them on the same terms. But although the Madras government offered six times more than he had ever before received, he positively refused to rent them

to the English. In consequence of this obstinacy on the part of Nizam Ally, Lord Clive determined to take possession of the districts at all events, and for this purpose obtained a grant of them from the emperor. The Madras government occupied Rajamundree by force, and it is not surprizing that Nizam Ally should have treated as mockery all assurances of their being actuated solely by motives of self-preservation. Encouraged by the deference with which representations were still made to him by the English, and by his alliance with the Mahrattas, Nizam Ally threatened the English with extirpation, and endeavoured to incite Hyder to invade the Carnatic. The Madras presidency, in considerable alarm, tried to form an alliance with Hyder, but he refused to receive the envoy. In this dilemma, Mr. Palk, the governor of Madras, referred to Lord Clive, who recommended a connection with the Nizam, which should have for its object the subjugation of Hyder, and an alliance for restraining the spreading power of the Mahrattas.

The prospect thus held out to Nizam Ally precisely suited his views. He wished to reduce Hyder, and to humble the Mahrattas; he knew the value of regular troops, and he readily listened to the proposals of the English; but as he had already leagued himself with the Mahrattas against Hyder, he deemed it most adviseable not to break with Mahdoo Rao, until he had effected the overthrow of the usurper of Mysore. A treaty, however, was concluded between Nizam Ally and the English, by which the Madras government agreed

to pay seven lacks of rupees a-year for four of the districts, or to assist Nizam Ally with two battalions of infantry and six pieces of cannon. In case the troops should be required, the seven lacks of rupees were to be appropriated for their expences.

The Mahratta court seem to have perceived the object of this combination, and Mahdoo Rao, without waiting for his ally, if such he could be termed, crossed the Kistna in the month of January, and, before the end of March, took Sera, Ouscotta, and Mudgerry, re leased the Ranee of Bednore184, and her adopted son, who had been confined in Mudgerry, and after levying thirty lacks of rupees185 of tribute from Hyder, and collecting nearly seventeen186 more, from different parts of the Carnatic, was prepared to return to Maharashtra before Nizam Ally had made his appearance. When the English and Nizam Ally wished to have brought forward their pretensions to share in the Mahratta tribute, their envoys were treated with broad and undisguised ridicule187. It is not positively known whether Mahdoo Rao was apprized of the ultimate design of the alliance between Nizam Ally and the English, nor is it ascertained what agreement existed between Nizam Ally and the Mahrattas, but we

have an unsupported assertion of Nizam Ally’s minister, Rookun-ud-dowlah, that his master had been duped by the Mahrattas for the third time188; at all events, it could not have escaped the observation of Mahdoo Rao, that the English in the war against Hyder, voluntarily appeared as auxiliaries to one of two contracting parties, and that, upon the subjugation of Hyder, Nizam Ally, by the English aid, could dictate, as the Mahrattas probably otherwise would have done, in any partition of his territories. This proceeding, therefore, on the part of Mahdoo Rao, which has been alluded to as ordinary Mahratta artifice to anticipate the plunder189, was a measure perfectly justifiable, for the purpose of effecting an important political object, and disconcerting the plans of his enemies. He recrossed the Kistna, in the end of May, leaving the Moghuls and their allies to settle with Hyder as they best could.

The subsequent treachery of Nizam Ally in joining Hyder against the English, and the circumstances which induced him, by a fresh act of treachery, to desert Hyder, and renew the treaty with the English, have been elsewhere distinctly and fully recorded190; and as they belong not to this history, it is only necessary to mention, in order to preserve a connexion with subsequent

events, that a new treaty was concluded on the 23d February 1768, between Nizam Ally and the English, which, though framed on the basis of that which was settled in 1766, differed from it in some very essential particulars; the most remarkable of which was, their arrogating to themselves the right and the power to dispose of Hyder’s territories. The treaty declared Hyder a usurper; the Carnatic Balaghaut was taken from him by Nizam Ally, as Moghul viceroy in the Deccan, and the office of Dewan, for the future management of that territory, conferred upon the English Company, for which they agreed to pay an annual tribute of seven lacks of rupees. Nizam Ally further consented to cede Guntoor, the remaining district of the northern circars, upon the death or misconduct of his brother Busalut Jung. The Mahrattas, without having applied to become parties to this absurd treaty, were, by a special clause to be allowed their Chouth from the territory thus disposed of. The Peishwa had no interference in the warfare which continued for some time between the English and Hyder; the line of conduct which he adopted, and which will be explained in the regular narrative of events, may be ascribed partly to policy, but principally to the internal situation of his empire.

Rugonath Rao, in the preceding year, after the campaign against Janojee, had set out on an expedition into Hindoostan accompanied by Mulhar Rao Holkar. The prosecution of an intended reduction of many places formerly in the possession of the Mahrattas, or tributary to them, was

obstructed, in the first instance, by the death of Mulhar Rao Holkar. His grandson Mallee Rao, only son of Khundee Rao, and a minor, succeeded to his possessions, but died soon after, which gave rise to a dispute between Gungadhur Yeswunt the Dewan, and Aylah Bye the widow of Khundee Rao, now lawful inheritor. The Dewan proposed that some connection of the family should be adopted by the widow; but to this Aylah Bye, although her Dewan’s proposal was approved of by Rugonath Rao, would by no means consent. Supported by her own troops, by the Peishwa, and by the voice of the country, she appointed Tookajee Holkar191, an experienced Sillidar, a great favourite with the late-Mulhar Rao, but no relation of the family, to the command of her army, retaining under her own management the civil administration of the extensive family Jagheer. To the death of Mulhar Rao Holkar may probably be attributed the inactivity of the Mahrattas192 during this campaign, and the failure of Rugonath Rao in an attempt to reduce the Rana of Gohud, a petty chieftain of the Jhat tribe, whose uncle rose into notice, under the Peishwa Bajee Rao, but who, upon the defeat of

the Mahrattas at Panniput, rebelled against them. Rugonath Rao, after a protracted siege of the town of Gohud, accepted a tribute of three lacks of rupees, and shortly after proceeded towards the Deccan, where he arrived in the month of August, some time after the Peishwa’s return from the Carnatic. On Mahdoo Rao’s intimating his intention of meeting his uncle at Toka, the latter strongly suspected that there was a plan laid for seizing him. The fact appears to have been, that Rugonath Rao’s views, at the suggestion of Anundee Bye, were directed to dividing the sovereignty of the empire, and conscious that attempts to strengthen his party had been discovered, he dreaded the consequences. Mahdoo Rao intended to make a last effort to reclaim his uncle, to repeat his offers of conceding a principal share in the administration, or to give him a handsome but moderate establishment in any part of the country where he might choose to reside. It was not easy to overcome Rugonath Rao’s suspicions so far as to induce him to meet Mahdoo Rao, but an interview was at length effected by the mediation of Govind Sew Ram193.

Rugonath Rao at first refused all offers, and expressed his determination to retire to Benares. Mahdoo Rao replied, that he thought such a resolution extremely proper, and indeed, that he must either take the share of the administration which was proposed, or have no interference whatever in the government. To this last proposal, Rugonath Rao, piqued at the decided tone which his nephew had assumed, affected the readiest compliance, and gave orders to his officers, in charge of the forts of Ahmednugur, Sewneree, Asseergurh and Satara, to obey the orders of Mahdoo Rao; – he declared that all he desired, before renouncing the world, was the payment of the arrears due to his troops, and a suitable provision for his family and attendants. Mahdoo Rao agreed to pay twenty-five lacks of rupees in three months, to place at his disposal a Jagheer, situated about the source of the sacred river Godavery, yielding twelve or thirteen lacks of rupees of annual revenue, and including six forts, amongst which were Trimbuck, Oundha, and Putta194; but Rugonath Rao was dissatisfied, and only sought a fit opportunity to assert his claim to half of the Mahratta sovereignty.

Mahdoo Rao, at this period, was courted by the English and Mohummud Ally on the one part, and

by Nizam Ally and Hyder on the other. Mr. Mostyn was sent to Poona, by the Bombay government, for the purpose of ascertaining the Peishwa’s views, and of using every endeavour, by fomenting the domestic dissensions, or otherwise, to prevent the Mahrattas from joining Hyder and Nizam Ally. An alliance was not to be resorted to, if it could be avoided, but if absolutely necessary, the conquest of Bednore and Soonda, regarding which the Mahrattas always regretted having been anticipated by Hyder, was to be held out as an inducement for engaging them in the English interests.

The Mahratta court evaded all decisive opinions or engagements, but candidly told the envoy that their conduct would be guided by circumstances. The Peishwa, however, could not quit the Deccan whilst his uncle’s conduct manifested symptoms of hostility; and Sukaram Bappoo’s intentions, always affectedly mysterious, continued equivocal.

Towards the end of the fair season Rugonath Rao had assembled a force of upwards of fifteen thousand men, with which, in hopes of being joined by Janojee Bhonslay, he encamped, first on the banks of the Godavery, and afterwards in the neighbourhood of Dhoorup, a fort in the Chandore range. It was at this period, when despairing of having another son, that Rugonath Rao adopted Amrut Rao, the son of a Concan Bramin, whose family surname was Bhooskoottee. His principal, supporters in rebellion were Dummajee Gaekwar, who sent him some troops under his eldest son Govind Rao, and Gungadhur Yeswunt, the Dewan of

Holkar, who was not only a zealous partizan of Rugonath Rao, but entertained a personal pique against the Peishwa, the origin of which is too remarkable to be omitted. At a public Durbar in Poona, after Rugonath Rao had retired from the administration, Gungadhur Yeswunt took an Opportunity of saying, in a contemptuous manner, “that in the present affairs, his old eyes could distinguish the acts of one who only saw with the eyes of a boy;” Mahdoo Rao, to the astonishment of all present, jumped from the musnud, or cushion of state, on which he sat, and struck him a violent blow on the face; a singular instance of the effects of anger in a Bramin Court, among a people remarkable for their decorum.

Mahdoo Rao, on hearing of the formidable rebellion under his uncle, in order to anticipate a design formed on the part of Janojee Bhonslay to support him, immediately marched to Dhoorup, where he attacked and defeated Rugonath Rao’s troops, forced him to seek shelter in the fort, obliged him to surrender, conveyed him a prisoner to Poona, and confined him in the Peishwa’s palace.

The season of the year prevented Mahdoo Rao from taking immediate notice of the hostile intentions of Janojee, but he was publicly engaged in negotiations with Nizam Ally and with Hyder, in which he had a triple object: his chief design was to punish Janojee, and his first care was to engage Nizam Ally in an alliance for that purpose; the second was to draw the tribute from Mysore without the necessity of sending Gopaul Rao’s army from Merich, as Hyder, fully occupied in

the war with English, might be thrown off his guard by his extreme anxiety to procure the aid of the Mahrattas; the third object was to deter the Bengal government from entering on an alliance earnestly solicited by Janojee, from the fear that Mahdoo Rao, aided by Hyder and Nizam Ally, would ruin the company’s affairs on the coast of Coromandel before their forces from Bengal could join Janojee in Berar.

The governor and council at Bombay, although the agent then at Poona, Mr. Brome, reported precisely as Mahdoo Rao wished him to believe, being less directly interested than Madras, were the first to perceive the depth of this well-planned scheme; and Hyder, as soon as his eyes were opened by finding that the tribute was required as a prelude to the Mahratta alliance, improved, on the deception, and endeavoured to turn the reports then in circulation to his own advantage, by drawing the presidency of Madras into an alliance with himself195.

Mahdoo Rao, when he gave out that his preparations were intended to assist Hyder, amongst other stratagems to mask his real designs, sent his fleet to cruize off Bombay harbour; but Visajee Punt, the commander from Bassein, on being called upon by the governor and council to explain his conduct, gave as an excuse, that he was watching two Portuguese ships, and assured the president that the Peishwa had no intention of breaking with

the English. This assurance strengthened their opinion, and was soon confirmed by reported commotions, the preparations of Janojee Bhonslay, and the advance of a combined army of Mahrattas and Moghuls, under the Peishwa and Rookun-ud-dowlah, towards Nagpoor.

Janojee laid a judicious plan for the campaign, and opposed the invaders on the old Mahratta system, in which Mahdoo Rao was less experienced than in the half regular kind of warfare to which his attention had been directed. The artillery, the Arabs, and the infantry partially disciplined, the numerous tents, and the heavy equipments of the Peishwa and Rookun-ud-dowlah, unfitted them for the active war of detachments which Janojee pursued.

The combined armies entered Berar by the route of Basum and Kurinja. Naroo Punt, the Soobehdar of the province, on the part of Janojee, attempted to oppose them, but was defeated and killed; his nephew, Wittul Punt Bullar, retired towards Nagpoor, where Janojee and Moodajee, with their families and baggage, were encamped. As the Peishwa advanced they moved off to the westward, and as no attempt was made to cut them off from Gawelgurh, as soon as Mahdoo Rao passed to the eastward, they lodged their families and baggage in that fortress, and were joined at Wuroor Zuroor, by their brother Sabajee, at the head of a large detachment. Mahdoo Rao plundered Nag-poor, Janojee made no attempt to save it, but moved to Ramteek, where his whole force united; Bimbajee, the fourth brother, having joined from

Chutteesgurh, Janojee then made a feint, as if intending to proceed towards the Peishwa’s tricts to the northward. Mahdoo Rao, however, was not tempted to follow him; he placed Thannas in various districts, collected the revenue all over the country, and laid siege to Chandah. Janojee, in the meantime, wheeled off to the westward, and marching with extraordinary diligence, passed Ahmednugur, and began to plunder the country on the route to Poona. Mahdoo Rao had at one time proposed, after his capital was destroyed by Nizam Ally, to surround it by a strong wall, but this design was, on mature consideration, abandoned, lest it should ultimately occasion irreparable loss, by holding out a security to property which was best insured by a dependance on the strong hill forts of Singurh and Poorundhur. The inhabitants, on Janojee’s approach, sent off their property as usual, and Mahdoo Rao, as soon as he was apprized of the route he had taken, sent Gopaul Rao Putwurdhun and Ramchundur Gunnesh with thirty thousand horse in pursuit of him; but Janojee still plundered in the neighbourhood of Poona, and Gopaul Rao was justly accused of being secretly, in league with him. The Peishwa and Rookun-ud-dowlah raised the siege of Chandah; Janojee moved towards the Godavery, pretending that he was about to give fair battle to the Peishwa in the absence of Gopaul Rao, whom he left at some distance in the rear. Nothing, however, was farther from his intention; he passed the Peishwa’s army near Mahoor, but detached Bappoo Kurundeea by a circuitous route, who suddenly fell upon

the baggage and succeeded in carrying off a portion of it. Both parties, however, were tired of the war, they had mutually sustained heavy loss; and Janojee, although hitherto as successful as he could have expected, was sensible that if hostilities continued they must end in his ruin; but his principal alarm was caused by some intrigues with his brother Moodajee, and he readily embraced the first overtures of pacification afforded by a message from Mahdoo Rao. A treaty, or in the language of the Peishwa, who did not admit the independence which treaty implies, an agreement was concluded, on terms extremely favourable to the Peishwa, on the 23d March196, eleven days prior to the masterly manoeuvres by which Hyder Ally dictated a peace to the English at the gates of Madras.

The agreement between Mahdoo Rao Peishwa, and Janojee Bhonslay, Sena Sahib Soobeh, was concluded at the village of Kunkapoor, on the north bank of the Beema, near Brimeshwur, and consisted of thirteen articles, by which Janojee restored the remainder of the districts he had received for deserting the Moghuls at Rakisbone, and gave up certain sequestrated shares of revenue, or an equivalent for what rightfully belonged to Futih Sing Bhonslay, Raja of Akulkote. The tribute of Ghas Dana, hitherto levied by the Sena Sahib Soobeh, from the Peishwa’s districts in Aurungabad, was discontinued, and in lieu of such tribute due

from any other district, belonging to the Peishwa or Nizam Ally, a stipulated sum was to be fixed, and paid by an order upon the collectors; but in case the Moghuls should not pay the amount, the Sena Sahib Soobeh should be at liberty to levy it by force; he was neither to increase nor diminish his military force, without permission from the Peishwa, and to attend whenever his services were put in requisition; to protect no disaffected Sillidars, nor to receive deserters from the Peishwa’s army; to maintain no political correspondence with the emperor of Delhi, the Soobehdar of the Deccan, the English, the Rohillas, and the Nabob of Oude. A Wukeel was permitted to reside with the English in Orissa, and at the Court of Nizam Ally, but his business was to be strictly confined to revenue affairs. Janojee Bhonslay also submitted to pay a tribute of rupees, five lacks and one (500,001), by five annual instalments197. On the other hand, the Peishwa agreed not to molest Janojee’s districts by marching his forces towards Hindoostan, by any unusual route; to pay no attention to the pretensions of his relations, as long as he continued their just rights; – he was to be permitted to send a force against the English, who were represented as troublesome in Orissa, provided his troops were not required for the service of the state. There are a variety of other items mentioned in the agreement, but the above are the most important; the form of the Sena Sahib Soobeh’s dependance upon the

Peishwa, is maintained throughout; but it seems more particularly marked, by avoiding the usual terms of an offensive and defensive alliance, instead of which, the Peishwa agrees, at the request of the Sena Sahib Soobeh, to assist him with troops, in case of an invasion of his territories by any other power.

Of the advantages obtained by Mahdoo Rao, Nizam Ally received three lacks of rupees of annual revenue; and one lack was conferred on his minister, Rookun-ud-dowlah198.

After the close of the campaign against the Raja of Berar, the Peishwa sent an army into Malys, under the command of Visajee Kishen Beneewala, accompanied by Ramchundur Gunnesh, Tookajee Holkar, and Mahadajee Sindia. Their proceedings will be hereafter detailed; but some circumstances connected with the last-mentioned person, domestic affairs at Poona, and operations in the Carnatic, demand our previous attention.

Mahadajee Sindia, after the death of his nephew, Junkojee, although his illegitimacy was against his succession, had, by his services and qualifications, established claims to the family Jagheer, which it would have been both impolitic and unjust to set aside, especially as there was no legitimate descendant of Ranoojee alive. His birth tended greatly to lower his respectability in the eyes of the Mahratta Sillidars, a circumstance which was a cause of Sindia’s subsequent preference for Mahomedans

and Rajpoots, and occasioned an alteration in the constitution of his army. Rugonath Rao, seemingly without any reasonable cause199, wished to see him appointed merely the guardian of his nephew, Kedarjee Sindia, the eldest son of Tookajee; an arrangement of which the Peishwa disapproved; and this difference of opinion not only widened the breach between Mahdoo Rao and his uncle, but ever after inclined Mahadajee Sindia to Nana Furnuwees, Hurry Punt Phurkay, and several others, the ostensible carcoons, but the real ministers of Mahdoo Rao.

When ordered to Hindoostan on the expedition just adverted to, after all the commanders had obtained their audience of leave, Mahadajee Sindia, presuming on the favour shown to him, continued to loiter in the neighbourhood of Poona. Mahdoo Rao, who at all times exacted strict obedience from his officers, had particularly desired that they should proceed expeditiously, in order to cross the Nerbuddah, before there was a chance of obstruction by the swelling of the rivers from the setting in of the south-west monsoon; but two or three days afterwards, when riding out to Theur, his favourite village, thirteen miles from Poona, he observed Sindia’s camp still standing, without the smallest appearance either of movement or preparation. He sent instantly to Mahadajee Sindia, expressing

astonishment at his disobedience and presumption, and intimating that if, on his return from Theur, he found a tent standing, or his troops in sight, he should plunder his camp and sequestrate his Jagheer. Mahadajee took his departure promptly; but this well-known anecdote, characteristic of Mahdoo Rao, is chiefly remarkable from the contrast it presents to the future power of Mahadajee Sindia at the Mahratta capital.

The Peishwa seized every interval of leisure to improve the civil government of his country. In this laudable pursuit he had to contend with violent prejudices, and with general corruption; but the beneficial effects of the reforms he introduced are now universally acknowledged, and his sincere desire to protect his subjects, by the equal administration of justice, reflects the highest honour on his reign. His endeavours were aided by the celebrated Ram Shastree, a name which stands alone on Mahratta record as an upright and pure judge, and whose character, admirable under any circumstances, is wonderful amidst such selfishness, venality, and corruption as are almost universal in a Mahratta court. Ram Shastree, surnamed Parboney, was a native of the village of Maholy, near Satara, but went early to Benares, where he studied many years, and upon the death of Bal Kishen Shastree, about the year 1759, was selected for public employment at Poona, without either soliciting or declining the honour of being placed at the head of the Shastrees of the court. As Mahdoo Rao obtained a larger share of power, Ram Shastree was at great pains to instruct him,

both in the particular branch which he superintended, and in the general conduct of administration. An anecdote related of him is equally creditable to the good sense of himself and his pupil. Mahdoo Rao, in consequence of the conversation of several learned Bramins, had for a time been much occupied in expounding and following the mystical observances which the Shasters enjoin. Ram Shastree perceived, that to oppose this practice by ordinary argument, would only lead to endless disputes with Mahdoo Rao, or rather with his associates; but one day, having come into the Peishwa’s presence on business, and found him absorbed in the contemplation enjoined to Hindoo devotees200, during which all other faculties are to be suspended, the Shastree retired; but next day, after making the few arrangements necessary, he went to the Peishwa and formally resigned his office, which is politely expressed, by intimating an intention of retiring to Benares. Mahdoo Rao immediately apologized for the apparent impropriety of his conduct the day before, by stating the cause, which he defended, as excuseable and praiseworthy. “It is only so,” replied Ram Shastree, “provided you entirely renounce worldly advantages. As Bramins have departed from the ordinances of their faith, and assumed the office of Rajas, it becomes them to exercise power for the benefit of their subjects, as the best and only apology for having usurped it.

It behoves you to attend to the welfare of your people and your government; or, if you cannot reconcile yourself to those duties, quit the Musnud, accompany me, and devote your life strictly to those observances, which, I fully admit, our faith enjoins.” Mahdoo Rao acknowledged the justness of the rebuke, and abandoned the studies which had misled him.

The benefits which Ram Shastree conferred on his countrymen were principally by example; but the weight and soundness of his opinions were universally acknowledged during his life; and the decisions of the Punchayets, which gave decrees in his time, are still considered precedents. His conduct and unwearied zeal had a wonderful effect in improving the people of all ranks; he was a pattern to the well-disposed; but the greatest man who did wrong stood in awe of Ram Shastree; and although persons possessed of rank and riches did, in several instances, try to corrupt him, none dared to repeat the experiment, or to impeach his integrity. His habits were simple in the extreme; and it was a rule with him to keep nothing more in his house than sufficed for the day’s consumption.

One of Mahdoo Rao’s first acts, was to abolish the system of forcing the villagers to carry baggage, a custom then so prevalent in India, that when first done away in the Mahratta country by Mahdoo Rao, it occasioned discontent among the men in power, and many secretly practised it. But the Peishwa having intelligence of a quantity of valuable articles conveyed in this manner, by

order of Visajee Punt, Soobehdar of Bassein, seized and confiscated the whole; remunerated the people for being unjustly taken from their agricultural labours, and at the same time issued fresh orders, which none, who knew his system of intelligence, ventured to disobey201.

In the ensuing fair season, Mahdoo Rao had leisure to turn his attention to affairs in the Carnatic. Hyder, after concluding peace with the English, and obtaining a promise of their eventual support, was under no alarm at the prospect of a war with the Mahrattas. He not only evaded their demands for the payment of arrears of tribute, but levied contributions upon some of the Poly-gars, tributary to the Peishwa; an encroachment which Mahdoo Rao was not of a disposition to tolerate. In the month of November he sent forward a large body of horse under Gopaul Rao Putwurdhun, Mulhar Rao Rastia, and the cousins of Gopaul Rao, viz. Pureshram Bhow, and Neelkunt Rao Putwurdhun.

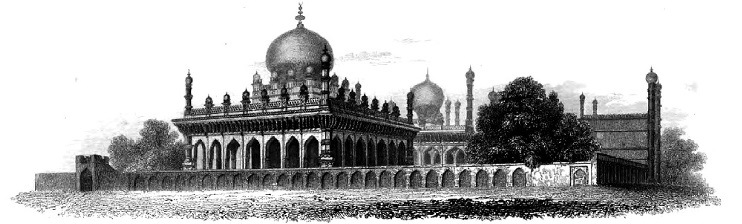

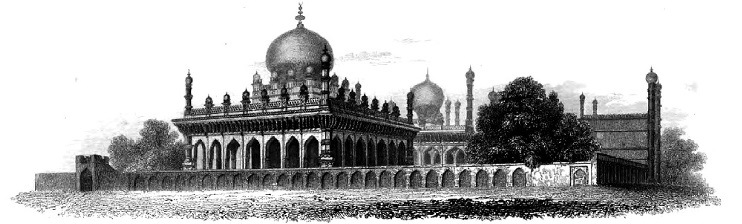

Mahdoo Rao followed, at the head of thirty-five thousand men, of whom, fifteen thousand were infantry. He rapidly reduced the two Balapoors, Kolhar, Nundedroog, Mulwugul202, and the greater part of the open country on the eastern boundary of Hyder’s territory, including sixteen forts, none of them considered of very great importance; and twenty-five fortified villages, of which he destroyed the greater part of the defences203. The fort of Mulwugul

was carried by an assault led by two rivals of the Ghatgay family, of Boodh and Mullaoree. Their hereditary disputes, known to have existed from the time of the Bahminee dynasty, had been repeatedly revived in the Peishwa’s camp, but though settled by a punchayet in favour of Nagojee Raja, Togiliar Rao, the other branch of the family, the bead of which was Bajee Ghatgay, being dissatisfied, both parties had solicited permission to decide the quarrel, according to the family privilege, “at the spear’s point,” to which Mahdoo Rao would not consent; but when the assault was about to take place, it was proposed, that of the two, he whose flag first appeared before the Juree Putka on the top of the rampart, should be confirmed in all the hereditary privileges. One of the family who carried the flag of Bajee Ghatgay was killed; Dumdairay, the person who had charge of the Juree Putka also fell, but Nagojee seized the standard, and planting his flag with his own band, hoisted the Juree Putka over it amidst an enthusiastic shout from the whole Mahratta army. Unfortunately the lustre of this gallant action was tarnished by the slaughter of the whole garrison204.

The Peishwa’s progress was for a time arrested at Nidjeeghul, a place of inconsiderable strength, which held out several months, and repulsed two assaults made by the Mahrattas, in one of which,

Narrain Rao, the Peishwa’s brother, was wounded205. It was at last stormed by the Polygar of Chittledroog, at the head of his Beruds206 a class of people who, as already noticed, are said to be originally Ramoosees from Maharashtra.

Hyder, as the Mahrattas advanced on the east, retired to the westward, where the country being closer, their cavalry were prevented from acting against him with effect. He never ventured within twenty kos of Mahdoo Rao, as his infantry would not face the Mahratta horse on a plain.; but a light force under Gopaul Rao, which was sent to watch his motions, and ravage the country, was surprised and put to flight by Hyder, on the night of the 3d or 4th March. This affair was attended by no advantage, the Mahrattas continued to plunder and ravage his territory, and Hyder hoped that they would retire to the northward of the Kistna, on the approach of the south-west monsoon207. But he was

disappointed. The state of Mahdoo Rao’s health compelled him to return to Poona in the beginning of June; but he left the infantry, and twenty thousand horse under Trimbuck Rao Mama, to prosecute the war. Hyder offered to pay the Chouth, but would not restore the amount exacted from the Polygars, as he conceived their submission to his authority in 1762, gave him a right to the tribute he had levied208.

Trimbuck Rao, before the season when he might expect the return of the Peishwa, gained several advantages, reduced the fort of Gurumconda, and some other garrisons.

Mahdoo Rao, as soon as the season permitted, marched from Poona, intending to have joined Trimbuck Rao, but being again taken ill, he gave over the command to Appa Bulwunt, the son of that Bulwunt Rao, who fell so much distinguished in one of the battles at Panniput. After the junction of Appa Bulwunt, the Mahratta army consisted of nearly forty thousand horse, with ten thousand infantry, and some guns. Hyder, with twelve thousand horse, and twenty-five thousand infantry, of whom fifteen thousand were regulars, and forty209 field guns, did not at first venture to take the field, and the Mahrattas encamped a short distance to the north of Seringapatam. Trimbuck Rao, in hopes of being able to draw Hyder from his position, retired a short distance to the northward, when

Hyder, who always kept up a correspondence with some of the Mahratta officers210, is supposed to have been deceived by false information, and took the field, imagining that a great part of Trimbuck Rao’s force was detached211. He was soon undeceived, and such was his impression, whether from having been formerly beaten by the Mahrattas, or from want of confidence in his army, a circumstance rare in a good officer, this man, who had fought with skill and bravery against British troops, did not dare to risk a battle, and at last fled, in the most dastardly and disorderly manner, towards his capital. The whole of his guns were taken, some thousands of his men, and fifteen hundred of his cavalry were destroyed; twenty-five elephants, several thousand horses, and the whole of his camp equipage, were the recorded trophies of the Mahrattas, who, as usual, boasted less of their victory than of their plunder.

After this success, Trimbuck Rao invested Seringapatam, but being almost destitute of men capable of working his guns, the attempt was conducted with more than the usual absurdity of a Mahratta siege. It was disapproved by Mahdoo Rao, whose object was to possess himself of Bednore and Soonda, during the ensuing season. Trimbuck Rao, after wasting five weeks before Seringapatam, retired in the middle of April to Turry Ghuree212, keeping a strong garrison in Belloor,

and exacting heavy contributions in various directions.

Before the roads were completely occupied, Hyder, in the beginning of June, attempted to draw a convoy of military stores with twenty pieces of cannon from Bednore to Seringapatam, but the whole, including the escort that accompanied them, were intercepted; and at last, so effectually did the Mahrattas cut off the communication, that Hyder’s Hircarrahs were obliged to pass through the Koorga Raja’s country, and descend the Ghauts in Malabar, as the only route to Bednore. On the 24th October the Mahrattas moved to Bangalore; Hyder, with about twenty thousand men of all descriptions, remained at Seringapatam strongly intrenched213. The only success which attended his arms, during the whole season, was achieved by his son Tippoo, who intercepted a very large convoy of grain proceeding towards the Mahratta camp. Hyder’s situation was considered critical, and a prospect of the total reduction of his country, which formed the only barrier between the Mahrattas and Madras, inclined the Bombay government to afford him their assistance, but the territory214 and subsidy, demanded as preliminaries on the one part, and the terms proposed on the other, were out of all proportion; besides which Hyder artfully endeavoured to make them principals in the war, by requiring of them to attack

Salsette, which at once put an end to the negotiation.

The governor and council at Madras deemed it of vital importance to support Hyder Ally, but they were prevented by the wishes of Mohummud Ally and the opinion of Sir John Lindsay, His Majesty’s minister plenipotentiary, both of whom, in the face of the late treaty with Hyder, urged the Madras government to unite with the Mahrattas215. But news of the increasing illness of the Peishwa, which was pronounced incurable in the month of March, alarmed all the Mahratta commanders at a distance from the capital; especially those who owed their situations exclusively to Mahdoo Rao. The design of reducing Soonda and Bednore was abandoned; and assigning as a reason, that the Mahratta Sillidars were desirous to return to their homes, which was also perfectly true, Trimbuck Rao listened to Hyder’s overtures. Negotiations began in the middle of April, when the Mahrattas were in the neighbourhood of Bangalore; and a treaty was concluded in June, by which, the Mahrattas retained the ancient possessions of the father of Sivajee216, besides Mudgerry and Gurumconda. Hyder likewise agreed to pay thirty-six lacks of rupees, as arrears and expences, and fourteen lacks, as the annual tribute, which he in future promised to remit with regularity; – all other Mahratta demands were to cease217.

Mahdoo Rao’s disease was consumption, but his health improved considerably during the monsoon, and great hopes were entertained of his recovery; the progress of his generals in Hindoostan had been still more important than his acquisitions in the Carnatic.

The army, which crossed the Nerbuddah in 1769, under Visajee Kishen, as chief in command, consisted, when the whole were united in Malwa, of nearly fifty thousand horse. Visajee Kishen and Ramchundur Gunnesh, besides Pindharees, had twenty thousand horse, of which, fifteen thousand belonged to the Peishwa. With Mahadajee Sindia there were fifteen thousand, and with Tookajee Holkar about the same number218. There was also a large body of infantry with a numerous artillery219, chiefly natives of Hindoostan and Malwa, including men of all casts. The Arabs, Abyssinians, and Sindians, of whom there was a small proportion, were accounted the best soldiers of the army, and were mostly obtained from the sea-ports of Cambay and Surat.

For some time after the fatal field of Panniput, the Mahrattas, in consequence of their domestic struggles, and the warfare to the south of the Nerbuddah, had little leisure to interfere with the politics of Hindoostan. Mulhar Rao Holkar, on one occasion, in the year 1764, joined the Rats when besieging Delhi, but soon quitted them, and returned to the Deccan.

A body of Mahrattas from Bundelcund, or Malwa, took service with Shujah-ud-dowlah, in the war against the English in 1765; but, excepting the temporary visit of Holkar to Delhi, above alluded to, the Mahrattas had not crossed the Chumbul, in force, for upwards of eight years.

The Abdallee king, after the great victory he achieved, bestowed the throne of the Moghuls on the lawful heir, Shah Alum; but as that emperor was then engaged in the well known warfare against the Nabob of Bengal, and the English, his son, the prince Jewan Bukht, assumed the ensigns of royalty during the Emperor’s absence. Shujah-ud-dowlah, Nabob of Oude, was appointed Vizier, and Nujeeb-ud-dowlah, Rohillah, was restored to the dignity of Umeer Ool Oomrah. After which, Ahmed Shah Abdallee quitted Delhi and returned to his own dominions.

Nujeeb-ud-dowlah remained with the young prince generally at the capital; but Shujah-ud-dowlah first repaired to his own government, and afterwards expelled all the Mahratta Carcoons, whom he still found remaining as collectors of revenue in the Doo-ab. He next proceeded to

Benares, where, having been joined by the emperor, they advanced together into Bundelcund, took Jhansee220, and would probably have driven the Mahrattas from that province; but in consequence of the flight of Meer Cassim from Bengal, Shujah-ud-dowlah, not content with affording him an asylum, espoused his cause against the English, a course of policy which led to his defeat at the battle of Buxar, on the 23d October 1764, when the emperor for a time placed himself under the protection of the English221. A treaty with Shujah-ud-dowlah, in August 1765, restored to him the principality of Oude, which had been subjugated by the British arms, recognised his title as Vizier of the empire, and established an alliance with the Company’s government.

The reader may recollect the manner in which the Moghuls, in the time of Aurungzebe, took possession of a province, and their mode of con, ducting its administration. To each district there was a Foujdar, or military governor charged with its protection and interior order, and a Dewan, or collector and civil manager. There were also Soobehdars and Nazims, who were military governors of large provinces, but these were merely gradations of rank, to each of which there was a Dewan. The Foujdar was the active efficient officer, the superiors were mere supervisors. These military governors, when the empire fell into decay,

styled themselves Nabobs222 and all who could maintain that appellation, considered themselves independent, though they embraced every opportunity of obtaining firmans, or commissions from the pageant emperor. The English, at the period of Meer Jaffeir’s death, had Bengal at their disposal, and the emperor’s person in their power. The youngest son of Meer Jaffeir was made Nabob of Bengal, Bahar, and Orissa, in February 1765223, and the East India Company, previously charged with the military protection of this territory, were appointed his Dewan in August following. The Emperor, Shah Alum, with the assigned revenues of Allahabad and Korah for his support, the only part of the conquered territories of Shujah-ud-dowlah, of which the English thought proper to dispose, continued to reside under the British protection, in hopes that they might be induced to send an army to place him on the throne of his ancestors.

In the meantime, the Prince Jewan Bukht remained at the Moghul capital, where Nujeeb-ud-dowlah exercised the entire powers of administration. Sooruj Mull, the Jhat Prince, was gradually extending his power and consequence: the Mahratta officer224 in Agra accepted his protection and admitted a garrison of his troops: he took Rewaree and Ferohnugur from a Beloochee adventurer

who possessed them in Jagheer; and at last, applied to Nujeeb-ud-dowlah for the office of Foujdar in the environs of the capital. These encroachments were so palpable, that Nujeeb-ud- dowlah was obliged to have recourse to arms, and gained an easy and unexpected victory by the death of Sooruj Mull, who was killed in the commencement of the first action225. His son, assisted by Mulhar Rao Holkar226, during the short period the latter was absent from the Deccan in 1764, besieged Delhi, but Nujeeb-ud-dowlah, by means of that secret understanding which always subsisted between him and Holkar, induced the Mahrattas to abandon the alliance and return to Malwa.

Such was the state of Hindoostan when the Peishwa’s army crossed the Chumbul, towards the latter end of 1769. Their first operations were directed against the Rajpoot princes, from whom they levied ten lacks of rupees, as arrears of tribute. (1770.) They next entered the territory of the Jhats, on pretence of assisting one of the sons of Sooruj Mull; as great contentions prevailed amongst the brothers. The Mahrattas were victorious in an engagement fought close to Bhurtpoor, and, after having overran the country, the Jhats agreed to pay them sixty-five lacks of rupees, ten in ready money, and the rest by instalments. They encamped

at Deeg during the monsoon, and Nujeeb-ud-dowlah, dreading their recollection “of sons and brothers slain,” opened a negotiation with Visajee Kishen to avert the calamities he apprehended227. The Mahrattas are mindful both of benefits and of injuries, from generation to generation; but they are not more revengeful than might be expected of a people so little civilized; and in this respect they seldom allow their passion to supersede their interest. Visajee Kishen listened to the overtures of Nujeeb-ud-dowlah with complacency; but Ramchundur Gunnesh and Mahadajee Sindia called for vengeance on the Rohillas. On a reference being made to the Peishwa, he so far concurred in Sindia’s opinion, that Nujeeb-ud-dowlah could never be a friend to the Mahrattas; but as they were endeavouring to induce the emperor to withdraw from the protection of the English, in which Nujeeb-ud-dowlah’s assistance might be useful, the conduct of Visajee Kishen was approved228. Accordingly Zabita Khan, the son of Nujeeb-ud-dowlah, was sent to join Visajee Kishen; but Nujeeb-ud-dowlah shortly after died, when on his route to Nujeebgurh, in October 1770229. Immediately after this event, Zabita Khan assumed his father’s situation at the capital.

The President and Council at Bengal, although it was upon the face of their records that, in 1766 Shah Alum had made overtures to the Mahrattas, were not at first apprized of his having renewed

the negotiation, and were therefore at a loss to account for the conduct of the Mahrattas, in not making themselves masters of Delhi; instead of which they took the route of Rohilcund.

The Rohilla chiefs behaved with no spirit; their country was entirely overrun; the strong fortress of Etaweh fell into the hands of the Mahrattas; and the whole of the Dooab, except Furruckabad, was reduced, almost without opposition. The territory of Zabita Khan was not exempt from their ravages; they likewise made irruptions into Korah, and preferred demands upon Shujah-ud-dowlah, which alarmed the English, and induced them to prepare for resisting an invasion which they deemed probable.

Shujah-ud-dowlah, however, maintained a correspondence with the Mahrattas the whole time; and the emperor, at last, openly declared his intention of throwing himself on their protection. They returned from Rohilcund to Delhi before the rains, and possessed themselves of every part of it except the citadel, where, on account of the prince Jewan Bukht, they refrained from excess, and treated him with courtesy. Zabita Khan would probably have been detained by them, but Tookajee Holkar ensured his safe retreat to Nujeebgurh. The Bengal presidency, at the head of which was Mr. Cartier, represented to the emperor the imprudence and danger of quitting their protection; but with sound policy, placed no restraint on his inclination, and Shah Alum, having taken leave of his English friends, was met by Mahadajee Sindia, escorted to the camp of Visajee Kishen,

under whose auspices he entered his capital, and was seated on the throne in the end of December 1771230. The Mahrattas now determined to wreak their revenge on the son of Nujeeb-ud-dowlah; a design undertaken with the entire concurrence of the emperor, who bore Zabita Khan a personal enmity, but it was principally instigated by Mahadajee Sindia, the chief director of the councils of Visajee Kishen, Ramchundur Gunnesh having returned to Poona in consequence of a quarrel with his superior. Shujah-ud-dowlah continued his correspondence with the Mahrattas, although he personally declined assuming his post as Vizier whilst they maintained supremacy at the Imperial court. But the principal object of Shujah-ud-dowlah, as it had been that of his father, was the subjugation of the Rohilla territory, to which the death of Nujeeb-ud-dowlah paved the way. He had no objections, therefore, to see these neighbours weakened by the Mahrattas, provided he could ultimately secure the conquest for himself; but he also perceived, that the result of a permanent conquest of Rohilcund by the Mahrattas would prove the precursor of his own destruction. The Rohillas knew him well, and dreading treachery, Hafiz Rehmut, whose districts adjoined Oude, could not be prevailed upon to proceed to the assistance of Zabita Khan, until assured by Brigadier General Sir Robert Barker, the officer in command of the British troops stationed in the Vizier’s territory, that no

improper advantage should be taken of his absence from the frontier231.

Several places were speedily reduced; an ineffectual resistance was opposed to Mahadajee Sindia and Nujeef Khan, at the fords of the Ganges, which they crossed in the face of the Rohillas, by passing many of their posts as if they had no intention of fording until much higher up the river, when, after throwing them off their guard, they suddenly wheeled about, dashed down upon one of the fords at full gallop, and crossing over, made a great slaughter. The Rohillas, in consequence, seem to have been completely panic-struck. Zabita Khan’s territory was reduced with scarcely any opposition; the strongest entrenchments, and even forts were abandoned, before a horseman came in sight232. Puttergurh, where considerable wealth, amassed by Nujeeb Khan was deposited, fell into their hands, and the Rohilla chiefs were compelled to the very measure which Shujah-ud-dowlah desired; namely, to form a defensive alliance with him against the Mahrattas, for which they paid him forty lacks of rupees, and by which he secured himself from the Mahrattas, strengthened his own resources, and weakened the means of resistance on the part of the Rohillas, on whose ultimate destruction he was bent.

Visajee Kishen returned to Delhi for a short time, in the Month of June; but the main body of the Mahrattas was encamped during the rains in the Dooab, of which they had taken almost entire possession. The constant applications of Visajee Kishen in urging demands, the eagerness with which his Bramin followers snatched at every opportunity of acquiring wealth, the sordid parsimony of their habits when absent from the Deccan, and that meanness and impudence which are inseparable in low minds, greatly disgusted the Emperor, and all who were compelled to tolerate their insolence and rapacity. Their behaviour gave Shah Alum such extreme offence, that he was willing to run any risk to rid himself of such allies. Zabita Khan, through Tookajee Holkar, was endeavouring to recover both his territory and his father’s rank at court. The Emperor would not listen to the proposal, and he at last engaged his General, Nujeef Khan, to resist the Mahrattas by force. Visajee Kishen was desirous of avoiding extremities, and referred for orders to Poona; but an event had occurred there, which, at the time it happened, was less expected than it had been some months before; Mahdoo Rao breathed his last at the village of Theur, thirteen miles east of Poona, on the morning of the 18th November, in the 28th year of his age233. He died without issue; and his widow Rumma Bye, who bore him a remarkable affection, immolated herself with the corpse.

The death of Mahdoo Rao occasioned no immediate commotion; like his own disease, it was at first scarcely perceptible, but the root which invigorated the already scathed and wide-extending tree, was cut off from the stem, and the plains of Panniput were not more fatal to the Mahratta empire, than the early end of this excellent prince. Although the military talents of Mahdoo Rao were very considerable, his character as a sovereign is entitled to far higher praise, and to much greater respect, than that of any of his predecessors. He is deservedly celebrated for his firm support of the weak against the oppressive, of the poor against the rich, and, as far as the constitution of society admitted, for his equity to all. Mahdoo Rao made no innovations; he improved the system established, endeavoured to amend defects without altering forms, and restrained a corruption which he could not eradicate.

The efficiency of his government in its commencement, was rather clogged than assisted by the abilities of Sukaram Bappoo. The influence of the old minister was too great for the talents of his young master; all actions deemed beneficial were ascribed to the former, whilst the unpopularity, which with some party is inseparable from executive authority, fell to the inexperienced Peishwa, and to Mahdoo Rao in a peculiar degree, by reason of an irritable temper, not always under command, which was his greatest defect. This influence on the part of the minister, a man open to bribery, prevented that respect for Mahdoo Rao to which he was entitled, and without which, the

ends which he aimed at establishing, were obstructed. Until after Rugonath Rao’s confinement, Mahdoo Rao was unknown to his subjects: shortly after that event he privately sent for Sukaram Bappoo, told him “that he found many of his orders disregarded, and that he was but a cipher in the government: whether this proceeded from want of capacity, or diligence on his own part, or any other cause, he was himself perhaps an incompetent judge, but he would put the question to his sincerity, and begged of him to explain the reason and suggest the remedy.” Sukaram immediately replied, “you can effect nothing until you remove me from office: – appoint Moraba Furnuwees your Dewan, when you can be your own minister.”

Mahdoo Rao respected the penetration which read his intentions, confirmed him in the enjoyment of his Jagheer, and followed his advice. He permitted Moraba to do nothing without his orders; he established a system of intelligence, of which the many exaggerated stories now related in the Mahratta country, only prove, that in regard to events, both foreign and domestic, he possessed prompt and exact information.

A review of his civil administration, if taken in, the abstract, would convey an indifferent idea of his merits: it must therefore be estimated by comparison, by the state of the society in which he was chief magistrate, and by the conduct pursued in the interior management and protection of his country, whilst harassed by the machinations of his uncle’s party, and constantly engaged in foreign

war. The brief summary which it is here proposed to give, will scarcely allude to the administration of his predecessors, but may convey some idea of the best government the Mahratta country enjoyed, under the Hindoo dynasty of modern times.

The root of all the Mahratta systems, even now in existence, however much disfigured or amended, whether on the banks of the Myhie and Chumbul, or the Kistna and Toongbuddra, is found in the institutions of Sivajee.

We have seen that Sivajee had eight officers of state; of them it need only be observed, that the supremacy and gradual usurpation of the Raja’s authority had also superseded that of the other Purdhans, as well as of the Pritee Needhee. Forms of respect instituted with their rank were maintained; but they were only of importance in the state according to the strength and resources of their hereditary Jagheers, and of a superior description of soldiery, who, on pay much inferior to what they might elsewhere have obtained, still adhered to some of them, with that pride of servitude to their chief, which, by its enthusiastic delusion, has caught the fancies of men in all uncivilized countries, and dignified military vassalage. Of all these personages, at the period of Mahdoo Rao’s death, Bhowan Rao, the Pritee Needhee, was the most considerable, both for the reasons mentioned, and from his warlike character.

In the different departments of the state under Sivajee, every separate establishment, when complete, had eight principal officers; all such officers,

as well as their superiors, were styled Durrukdars, and although declared not hereditary at the time of their institution, they generally descended in the usual routine of everything Hindoo. Precedent, however, that grand rule of sanction to Mahratta usurpation, soon became, whilst anarchy prevailed, a mere name for the right of the strong, and the title of Durrukdars, like every other claim, was only regarded according to circumstances.

The general distribution of revenue planned by Ballajee Wishwanath, was a measure wholly political, but it was ingrafted on the revenue accounts of every village, the ordinary forms of which have been explained in the preliminary part of this work; upon the balance of assessment, or government share, the artificial distribution alluded to invariably followed; although seldom in the uniform manner laid down upon its first establishment in the year 1720. Separate collectors did not always realize those specific shares; but, even up to this day, distinct claims, such as Surdeshmookhee, Mokassa, &c. are frequently paid to different owners, and tend to render the accounts extremely intricate. A fixed district establishment, founded on that of Sivajee, but more or less complete, was preserved, until a very late period. Unless in the old Jagheer districts, the appointment of Durrukdars, during the life of Shao, remained in the gift of the Raja. The patronage however of one office or Durruk, was bestowed by the Raja Shao, either on Bajee Rao, or on Ballajee Rao immediately after his father’s death; the patronage so conferred was that of the Furnuwees; hence in the old accounts

of the Peishwa’s districts after the death of Shao, all those holding the office of Furnuwees, superseded their superiors the Muzzimdars; and thus the Peishwa’s Furnuwees became, under the Peishwa’s government, precisely what the Punt Amat was under that of the Raja. These two, the Furnuwees and Muzzimdar, were invariably kept up, as were the Dufturdar and Chitnees; but the appointment of Dewan was not general, nor of the Karkanees, Potnees, and Jamdar. Durrukdars were only removable by government, but a number of car-coons, in addition to the ordinary establishments, were introduced by Ballajee Rao, who were displaced at the pleasure of the immediate chief officer of the district. The useful situation of Turufdar, or Talookdar, was always preserved, but generally under the appellation of Shaikdar.

These details are enumerated, because the arrangement for the land revenue in Maharashtra is the basis of civil government; and, indeed, the good or bad revenue management of the districts of any country in India is the surest indication of the conduct of the administration.

Under Mahdoo Rao the same heads of districts were continued as had been established by his uncle, Sewdasheo Rao Bhow; except that upon the death of the Sursoobehdar Balloba Manduwagunnee, who effected the great reforms between the Neera and Godavery, he did not appoint a successor to that situation; but the Sursoobehdars in the Concan, Candeish, and Guzerat234, were always

continued. The appointment of a Mamlitdar was declaredly for the year, but he was not removed during good behaviour: the amount of his collections varied; generally, however, they were not above five lacks, and seldom below one lack of rupees annually. At the commencement of the season he was furnished by government with a general statement, which contained his instructions, and included the expected receipts, the alienations, and expenses; which last he was not to exceed, but upon the most satisfactory grounds. In the detail of the expenses were the salaries, including not only food, clothes, and every necessary, but the adequate establishment and attendants for each of the government servants, according to their rank and respectability. Besides these authorized advantages, there was a private assessment over and above the regular revenue, at which the government connived, provided the Mamlitdar’s share did not amount to more than five per cent. upon the actual collections. This hidden personal emolument was exactly suited to the genius and habits of Bramins, who, by a strange, though perhaps not a peculiar perversion, prefer obtaining an emolument in this underhand manner, to honestly earning four times as much.

The private assessment was supposed to be favourable to the cultivator, as well as pleasing to the Mamlitdar and district officers. Mahdoo Rao prevented the excess of the abuse by vigilant supervision, and by readily listening to the complaints of the common cultivators; as to the village officers, they all participated, and from them information

could only be obtained through some of the die,- contented hereditary claimants, whose statements were often fabricated, and so difficult to substantiate, that the government, much occupied by its great political transactions, generally made it a rule only to prosecute the chief authorities on great occasions, to take security from interested informants before examining the proofs, and to leave minor delinquency to the investigation of Mamlitdars. It might be supposed that a system so defective, with the door of corruption left open by the connivance of government, would be followed by every act of injustice, oppression, and violence; but the evils fell more on the state than on individuals; and at that time the Mahratta country, in proportion to its fertility, was probably more thriving than any other part of India.

The Mamlitdar, on his appointment, opened an account-current with government, and was obliged to advance a part of the expected revenue, for which he received a premium of two per cent., and one per cent. monthly interest, until the periods at which the collection was expected, when the interest ceased. This advance, which was both a security and convenience to government, and all revenue transactions whatever, were managed by the agency of the Soucars, or Indian bankers; but many persons employed their private property in the prosecution of such agency, in which there was often a great deal of speculation, but, with ordinary caution, large returns were obtained with very little risk. Thus the advance of money on the land-revenue became something like national funds,

partaking of the benefits of prompt supply, and the evils of fictitious credit.

At the end of the season, when the Mamlitdar’s accounts were closed, they were carried by the district Furnuwees to Poona, and most carefully examined before they were passed.

Mahdoo Rao encouraged the Mamlitdars to reside in the districts, keeping their Wukeels at Poona, but when that was impracticable, the affairs of the district were more scrupulously investigated.

The management of the police, and the administration of civil and criminal justice, were in a great degree intrusted to the Mamlitdars. The police magistrates were the Patell, the Mamlitdar, and, where the office existed, the Sursoobehdar. The Deshmookhs and Deshpandyas were left in the enjoyment of their hereditary rights, but their ancient power was suspended, and though permitted to collect their own dues, they were seldom referred to, except in ascertaining local usages, and occasionally in arbitrating differences. The police, except in the city of Poona, was very imperfect; but considering the defective state of the executive authority, even in the best times of the Mahratta government, and the unsettled predatory habits of so large a portion of undisciplined soldiery accustomed to violence and rapine, it is, at first view, surprising, that the lives and properties of the peaceable part of society were so secure. But the military were pretty equally dispersed; every village could defend its inhabitants or avenge aggression; and members who disgraced the community were too much bound by the opinion of their family

connections, their own interests, and the power of the village officers, to become entirely lawless. The Mahratta usage, of generally returning during the rains, preserved all those ties; and though it might prove inconvenient to an ambitious sovereign, it greatly tended to domestic order and tranquillity. The great use which the Peishwas made of attachment to wutun, and the preference in promoting an officer, shown to those who could boast of hereditary rights, was in many respects a most politic and judicious mode of encouraging a species of patriotism, and applying national feelings to purposes of good government.

In the Mahratta country, the most common crimes were thieving and gang robbery, murder and arson. The two first were more common to Ramoosees and Bheels than to Mahrattas, and were punished by the loss of life or limb; murder for revenge was rarely considered a capital offence, and very often, in hereditary disputes, a murder, where risk attended it, was considered rather a creditable action. The ordinary compromise with government, if the accused was not a rich man, was three hundred and fifty rupees. The facility of eluding justice, by flying into the territory of some other authority, was the greatest obstruction to police efficiency.

For great crimes, the Sursoobehdars had the power of punishing capitally; Mamlitdars in such cases required the Peishwa’s authority. The great Jagheerdars had power of life and death within their respective territories. Bramins could not be executed; but state prisoners were poisoned, or

destroyed by deleterious food, such as equal parts of flour and salt. Women were mutilated, but rarely put to death. There was no prescribed form of trial; torture to extort confession was very common; and confession was generally thought necessary to capital punishment. The chief authority, in doubtful cases, commonly took the opinion of his officers; and some Mamlitdars in the Satara country, under both the Pritee Needhee and Peishwa, employed Punchayets to pronounce on the innocence or guilt of the accused; but this system can only be traced to the time of Shao; and though so well worthy of imitation was by no means general, nor are its benefits understood or appreciated in the present day.

In civil cases the Punchayets were the ordinary tribunals, and the example of Ram Shastree tended greatly to their improvement. Excepting where Ram Shastree superintended, they were a known, though unauthorized source of emolument to the members; no doubt, frequently corrupt and unjust in their decisions: but Punchayets were popular, and their defects less in the system itself than in the habits of the people.

The nominal revenue of the whole Mahratta empire, at the period of Mahdoo Rao’s death, was ten crores, or one hundred millions of rupees; but the amount actually realized, including the Jagheers of Holkar, Sindia, Janojee Bhonslay, and Dummajee Gaekwar, together with tribute, fees, fines, contributions, customary offerings, and all those sources independent of regular collections, which in the state accounts come under the head of extra

revenue235, may be estimated at about seventy-two millions of rupees, or about seven millions of pounds sterling annually236. Of this sum, the revenue under the direct control of the Peishwa, was about twenty-eight millions of rupees; in which estimate is included Mahdoo Rao’s personal estate, kept distinct from the public accounts, but which seldom amounted to above three lacks of rupees, or thirty thousand pounds sterling a-year; he was,-however, possessed of twenty-four lacks of personal property at his death, which he bequeathed to the state.

From the vast acquisitions of Ballajee Rao, his lavish expenditure, and the numerous Jagheers and Enam lands which he conferred, it is a common opinion in the Mahratta country that he had a greater revenue than any other Peishwa; but he never had time to collect the revenues in many parts of India temporarily subjugated by his armies. The average collections, in any equal number of years, were greater in the time of Mahdoo Rao

than in that of his father; although in the season 1751 – 52, Ballajee Rao realized thirty-six and a half millions of rupees, which exceeded the highest collection ever made by Mahdoo Rao, by upwards of two millions. The state was much in debt at Mahdoo Rao’s accession; and although, at his death, by reckoning the outstanding balances, and by bringing to account the value of stores and other property, there was a nominal sum in its favour of sixty-five millions of rupees; yet the treasury was exhausted, no part of this amount being available. On a complete examination237 of the accounts, the government of the Peishwas seems always to have been in debt, or embarrassed from want of funds, till after the period of Bajee Rao’s connection with the English.

The ordinary army of the Peishwa, without including the troops of Bhonslay, Gaekwar, Sindia, or Holkar, amounted to fifty thousand good horse. Neither his infantry nor artillery were considerable; and, after providing for his garrisons, the ordinary number in the time of Mahdoo Rao was about ten thousand, of whom one third were Arabs, and the greater part Mahomedans. It was usual, however, to entertain large bodies of infantry when

the Peishwa took the field, but they were always discharged on returning to Poona. The Hetkurees, or Concan infantry, are said to have been preferred to the Mawulees, perhaps on account of the attachment of the latter to the house of Sivajee238.

Calculating the contingent which Gaekwar and Bhonslay were bound to furnish, at from ten to fifteen thousand, taking the lowest estimate of Holkar’s and Sindia’s army at thirty thousand, and allowing three thousand from the Powars of Dhar, the Peishwa could command about one hundred thousand good horse, exclusive of Pindharees.

183. This is another reason for supposing that there is a mistake of a year in stating Sulabut Jung’s confinement on the 18th July 1761, such a circumstance must have transpired at Bengal long before 11th December 1761, which is the date of the letter containing the proposal to the Bombay government.

184. She died on the way to Poona. – Mostyn’s Despatches.

185. Poona State Accounts. Colonel Wilks says, thirty-five lacks, and that Sera was at that time given up to Hyder in exchange for Gurumconda. Of this last transaction no mention is made in the state accounts, or in the despatches of Mr. Mostyn, resident at Mahdoo Rao’s court.

186. Rupees 1,695,777.

187. Wilks, vol. ii. page 16.

188. Wilks, vol. ii. page 15. The reader has it in his power to judge of the occasions to which Rookun-ud-dowlah alluded, first, in regard to Rugonath Rao, and second, in the late campaign against Janojee Bhonslay.

189. Wilks, vol. ii. page 6.

190. See Colonel Wilks’ South of India, vol. ii.

191. Tookajee Holkar paid a Nuzur or fee to the Peishwa’s government, on being appointed commander of Mulhar Rao’s troops, of rups. 1,562,000. (State Accounts, Poona Records.)

192. The reader acquainted with the history of British India, will recognise the first appearance of Rugonath Rao’s army in Bundelcund, as that which occasioned the alarm at Korah during a period of serious commotion. See Mill’s British India, page 251. volume ii.

193. Mr. Mostyn, the British envoy at the court of Poona, says, by the mediation “of Sukaram Bappoo.” (Secret Despatches, dated Poona, 5th December 1767.) Sukaram, according to his usual duplicity, was intriguing with both parties, that he might at all events be able to retain his place. He would not incur the risk of interference in a reconciliation which he foresaw would only be temporary. Mr. Mostyn also states, that “Mahdoo Rao, instigated by his mother, certainly had intentions of Seizing his uncle at that interview;” but as he mentions this on hearsay evidence, respecting an intention, and that too relating to what had taken place prior to his arrival at Poona, although his opinion has been generally followed on this point, I have preferred the authority of the natives of the country, who concur in imputing such a wish to Gopika Bye, but no such design to Mahdoo Rao.

194. Mahratta MSS. and Bombay Records.

195. Colonel Wilks has overlooked the Bombay letters on this point, Hyder was certainly a master at left-handed diplomacy. Bee vol. ii. page 117. Wilks’ South of India.

196. 14th Zilkad, Soorsun 1169. The Bombay Records mention the treaty between the Peishwa and Janojee as having taken place 23d April; in which, if there be no error in my calculation, they have made a mistake by one month.

197. This payment of five lacks is the only part of the agreement which came to the knowledge of the Bombay government.

198. Mahratta MSS. and copies of original agreements from the Poona records.

199. Many years after this period, in a despatch from Colonel Palmer, resident at Poona, 8th June 1798, it is mentioned, that Rugonath Rao conferred Sindia’s Jagheer on Mannajee Phaksay; but the Mahratta manuscripts do not allude to such a transaction.

200. That sort of contemplation which the Mahrattas express by the single word Jhep.

201. Some say that Mahdoo Rao exacted a heavy fine, besides confiscating the property.

202. Wilks.

203. Bombay Records.

204. Mahratta MSS., and a family legend known to every individual of the clan. of Ghatgay, although, in their usual loose way, they mention different names for the fort which was the scene of Nagojee’s exploit.

205. By a bullet in the hand. Mahratta MSS.

206. Wilks. The anecdote given by Colonel Wilks of the mutilation of the captive garrison is not preserved in the Mahratta country, therefore as a mere anecdote I am not authorized in repeating it, although it is very characteristic of the anger, the violence, and the generosity of Mahdoo Rao. There is, however, an anecdote given by Colonel Wilks, which I must remark, respecting Appajee Ram, vol. ii. page 14. It might do for the licentious court of Poona at any other period, but even, if authentic, which I cannot discover, it conveys a wrong impression. Mahdoo Rao would excuse want of form, and even an ebullition of anger, but he never tolerated indecency or impertinence.

207. Letters from the Bombay deputies, Mr. Richard Church and Mr. James Sibbald, from Hyder’s camp.

208. Mahratta MSS. Bombay Records. Wilks.