CHAPTER XII

NARVIK—DELAYING OPERATIONS

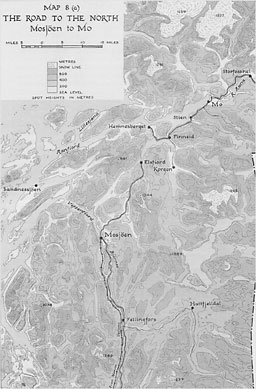

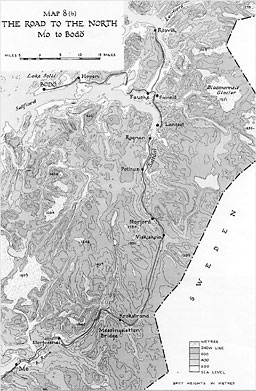

See Maps 8 (a), facing page 186, and 8 (b), facing page 192

TO THE SOUTHWARD[1]

Towards the end of April the second stage in the Norwegian campaign, which we have just traced in outline, opened with the first movement of British troops into the region south of Narvik. By the time they came into action there on 10th May, the siege of Narvik was also moving towards its denouement; but it will be convenient to treat first the contemporaneous operations farther south. The distances along the North Norwegian coast are very great: from Trondheim to Narvik is about 360 miles in a straight line, a form of measurement which has meaning only for air transport. The only town of any size along the route is Bodö, with a population of 5,000, though Mo i Rana,1 connected by a poor quality road with Sweden, was nearly chosen by the Norwegian Government for its temporary seat instead of Tromsö.2 Otherwise it was a region of mountains and fjords, attracting little population or traffic other than the coastal traffic through the Leads, its railway not yet functioning past Grong (the junction for Namsos), the single highroad to the north interrupted by several ferries south of Bodö, and beyond Bodö non-existent until the approaches to Narvik were reached. But, as we have already seen, the withdrawal of the Allied forces from the Trondheim area meant that the Germans might be expected to advance northwards up the coast until their air bases, if not their actual troops, could turn the besiegers of Narvik into the besieged.

As early as 21st April, a trawler had been sent to report on facilities at Mosjöen, a tiny port at the head of the Vefsenfjord about ninety miles north of Namsos (150 miles by road), and five days later the Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet, mentioned it again, apparently thinking that it would be feasible to relieve pressure at Namsos if a suitable landing place could be found there or elsewhere in the same direction. But it was not until the decision had been taken to leave Namsos altogether that operations north of that town became urgently necessary. On 27th April General Carton de Wiart's headquarters passed on to the War Office information received from

--177--

their Norwegian allies that the enemy intended to occupy Mosjöen, Two days later a message from General Massy stated that it was essential to deny Mosjöen to the enemy. His plan was that one detachment should be sent from Mauriceforce direct to Mosjöen by sea, and a second detachment, with the available transport, left as a rear-guard at Grong, east of Namsos, to hold up the enemy along the road north. This second detachment might, if necessary, be composed of skiers only. General Carton de Wiart and General Audet were, however, equally opposed to providing the rear-guard.3 The ski troops were not sufficiently numerous to achieve much and would be at the mercy of air attack; reconnaissance had shown the road to be impassable during the thaw for the motor transport required to supply them; and in any case the skiers were needed in their present positions to cover the evacuation. The matter remained under discussion as late as 2nd May, when there was a further conference between General Carton de Wiart and General Audet because direct instructions for a French detachment to be posted at Grong had been received by the latter from General Gamelin. But the original view that such a rear-guard could not be set up because it could not withdraw by road to Mosjöen was maintained.

As to the practicability of a retirement by road at the date given, enquiry from the Norwegians would perhaps have been pertinent. According to Colonel Getz,[2] the line of the uncompleted railway had been cleared of snow by the 19th; by the 26th the supplies for his brigade were being brought overland from Mosjöen, and on 1st May he was advising the Norwegian Legation in London, who were purchasing stores for him, of the good connections available between Mosjöen and Grong.4 A Norwegian battalion based on Mosjöen had been moved south to Grong on 21st April; it moved back with no great difficulty along the same route in the first week of May—130 miles by rail and 35 miles, on high ground in the middle where a railway bridge awaited completion, by a shuttle service of lorries.

The other half of the plan put to General Carton de Wiart was carried out, though on a reduced scale. A party of a hundred Chasseurs Alpins and a two-gun section of a British light anti-aircraft battery were sent by sea from Namsos in the only available transport, a destroyer, on the night of 30th April, arriving at Mosjöen late next day. unobserved from the air. A week later the French were replaced by British troops, so that the defence of Mosjöen and the subsequent operations became exclusively a British-Norwegian venture. Meanwhile, as previously related,5 the forces at Narvik under Lord Cork had received orders to safeguard the main intermediate

--178--

point at Bodo and a company of Scots Guards was sent to that area, so that the delaying operations to the southward henceforth had Bodo to fall back upon as an outpost protecting our operations at Narvik.

The situation was difficult, since British naval control of the inshore routes, which might have been expected to make our successive positions along the coast more tenable, was much impaired by the threat of air attack in the narrow waters of the fjords. There was no proper landing ground known to us south of Narvik: a search for possible sites to be developed round Bodö, Mösjoen, and Mo—in that order of priority—was ordered by the Air Ministry on 30th April. Four days later the R.A.F. reconnaissance party came to Bodö in two flying boats chartered from Imperial Airways; bombs began to fall within half an hour of the arrival of the second aircraft and reduced them both to wreckage.[3] Clearly there was no immediate prospect of providing air cover, and the needs of Narvik made it impossible to attempt any serious anti-aircraft defence. The Norwegian forces with which we were now to co-operate might indeed be expected to be apt for delaying operations, since they knew the country. Unfortunately, one battalion of the local regiment had been posted before 9th April to the Kirkenes area, leaving only a reserve battalion of uncertain value and the battalion referred to above, which was falling back on Mosjöen from Grong. This battalion was shaken, first by the Namsos capitulation, then by a railway accident, in which seven of its men were killed, and finally by a curious dispute as to the verification of orders received from the Norwegian High Command for the demolition of road and railway as they withdrew. One consequence of declining morale was that their demolitions proved to be quite ineffective. The brunt of any attack would clearly have to be borne by the British troops now beginning to arrive in the area from home, under orders to fight a series of delaying actions in circumstances of recognised inferiority to the enemy but without any definite prescribed time-table.

Scissorsforce was brought to Norway in three flights by single transports under destroyer escort. No. 1 Independent Company landed on 4th May at the head of the Ranfjord, at Mo, 54 miles north of Mosjöen by road. No. 3 Independent Company, to be joined later by No. 2 Company, landed much farther north at Bodö, and Scissorsforce headquarters was set up at the same time where the Scots Guards company had already established themselves, at the village of Hopen, eleven miles east of that town. The initial actions—apart from enemy air attacks, which began at Mo the day after No. 1 Company's arrival—were therefore the concern of the 4th and 5th Companies, these being the troops that replaced the French at Mosjoen on the night of 8th/9th May. No. 4 Company was disposed

--179--

so as to protect Mosjoen from the sea and to guard the first part of the road to Mo, while No. 5 Company moved south to link up with the Norwegians. Colonel Gubbins, who had landed with them, learnt that the Norwegian battalion, after its attempted reorganisation in Mosjöen, had gone forward again only 400 strong; indeed, the reports reaching the Norwegian High Command in the north were such that a staff officer was already on his way south to stiffen resistance.[4] Colonel Gubbins found the Norwegians at Fellingfors, twenty-five miles south of Mosjöen; there a side road led to the snowbound Hattfjelldal airfield up the East Vefsna valley and the demolition of the river bridge gave a line of defence. These troops were driven in by the Germans on the 9th, only four days after the latter had started their advance from Grong. Our own position was then being established nearer Mosjoen, at a point where the Björnaa river forms a lake and a long stretch of road is exposed to fire from the steep hillsides shutting in the water. No. 5 Independent Company had a party of two platoons (100 strong) on one flank of the two Norwegian companies,[5] while its third platoon defended the alternative approach along the line of the railway at the bridge over the Vefsna river, which was duly blown. In the early morning of 10th May the enemy vanguard, cycling incautiously down the road, was ambushed and destroyed to the number of about fifty men.[6] But a little after midday German pressure along both road and rail routes drove our forces back towards Mosjoen, which was some ten miles distant. Colonel Gubbins had hopes of taking up a new position on the outskirts of the town, but there is no natural line of defence and both the British and the Norwegian commander concluded that a further withdrawal beyond Mosjoen would be necessary. Colonel Gubbins thereupon sent orders to No. 1 Company at Mo to safeguard the line of the Ranfjord, which he would reach about halfway along the route of his retreat. It was of course intended that the British-Norwegian withdrawal should be made as slow, and the German advance as costly, as possible. This seemed a reasonable proposition, since the German force had advanced overland from Grong over the long route which we had believed to be impracticable at this season, and would presumably have to use that same route as its line of communications for any further progress.

But on this same day—10th May, the day on which the Germans broke into Holland and Belgium—they staged a further coup in Norway, which a Norwegian historian calls 'as audacious as the original invasion'.6[7] A party of about 300 German troops had been embarked near Trondheim in the Norwegian coastal steamer Nord-Norge, which had a crew drawn from the German destroyers. After a twenty-four-

--180--

hour delay due to a submarine alarm, this vessel left Trondheimsfjord under escort of two aircraft, and set its course north towards the scene of the present operations. The movement was observed by the Norwegian coast watch in the early morning and reported to British Naval Headquarters at Harstad. The first definite news was received there at 10. 15, but it was not until 11.55 that orders were sent to the only ships available—the anti-aircraft cruiser Calcutta, which was with a convoy fifty miles west of Skomvaer Light, and the destroyer Zulu at Skjelfjord. The Calcutta, had she proceeded at once, alone, and on the right course, might have intercepted the enemy; but more than two hours elapsed before a second signal gave Mo as the possible destination, and in any case the Zulu could not meet the cruiser earlier than 5 p.m., off the Myken Light. The two ships were then about forty miles north of the Ranfjord, which they entered behind the enemy.[8]

But by seven o'clock the Germans had completed their voyage, for their intended landing-place was nearer than we supposed—at Hemnesberget, fifteen miles west of Mo on the seaward edge of the Hemnes peninsula, from which the route between Mosjöen and Mo could be effectively cut. The arrival of the steamer was preceded by that of two Dornier seaplanes, which put ashore about forty men with mortars and machine guns west of the town and then dropped bombs on it. A platoon from No. 1 Independent Company was still remembered there nine years later as having fought with determination through the streets, but they could not hope to hold the quay and were forced eventually to make their escape as best they could by boat to Mo or to the neck of the peninsula at Finneid, where they were joined that night by the rest of No. 1 Company and by about 120 Norwegian troops with four heavy machine guns. Meanwhile the two British ships had come on the scene about one and a half hours behind the Germans, and had sunk their ship, but not before two mountain guns had been landed as well as all the men.[9] Next day a small fleet of seaplanes was at work bringing in stores which would help to replace lost cargo.

Colonel Gubbins had already withdrawn No. 5 Company through No. 4 Company to a position north of Mosjöen. But a move in that direction was now blocked farther on, so Mosjöen and district had to be abandoned forthwith, leaving the Germans free to improvise a forward air base in this area if they could. No. 4 Company were embarked in a small Norwegian steamer the same evening at and near Mosjöen, No. 5 the next morning at a point farther down the fjord; the Light Anti-Aircraft section which had originally accompanied the French to Mosjöen was also embarked, but had to destroy its guns. They landed at Sandnessjöen on the north side of the large island at the mouth of the Vefsenfjord, where two destroyers made

--181--

touch with them in the early morning of the 12th, and were brought on to Bodö partly by destroyers and partly by a local steamer under destroyer escort. By 4 a.m. on 11th May Mosjöen was already in German hands. As for the Norwegians, their reserve detachments collected at Mosjöen had already been despatched to Mo by sea, but the battalion with which our Independent Companies were cooperating went back overland from Mosjöen to Elsfjord, half-way to Mo, where the road was interrupted by a ferry route terminating at Hemnesberget. That terminus being no longer available, they had to leave the ferry at a point farther down, on the road north from Korgen, which would bring them past the neck of the Hemnes peninsula the position at Finneid—to Mo. But their heavy equipment was all abandoned and their military value more than proportionately diminished.

Even before the catastrophe at Hemnesberget, Colonel Gubbins's initial report from Mosjöen had aroused serious misgivings at headquarters at Harstad, where General Ruge's liaison officer also had instructions to give a daily reminder about the importance of stemming the German advance from the south. Lord Cork's proposal that the southern front be reinforced, made on 9th May, was welcomed by General Mackesy, who that evening put the Scots and Irish Guards at short notice to move to Mo. Brigadier Fraser, who had now returned to duty, was given command of all British troops in the area, and three companies of Scots Guards, with four 25-pounders and four light anti-aircraft guns, landed at Mo in the early morning of the 12th. The ships conveying them fired on the wharf at Hemnesberget on their way. But although they included an anti-aircraft cruiser and a sloop, the weight of air attack, both at Mo itself and in the approaches through some forty miles of narrow waters, was such that an agreed report was sent back, saying that large ships other than anti-aircraft cruisers ought not to enter the fjord. Two further attempts were made to harass the enemy on the Hemnes peninsula by naval bombardment, but it was not deemed possible to meet the Army's request for ships to be kept in the area so as to hamper any German advance across or alongside the water.

An attack from Finneid against Hemnesberget had been made by the Norwegians on the 11th. They penetrated about halfway along the road between the two places but were then driven back by German gunfire. The recapture of Hemnesberget was considered again next day when the Scots Guards had arrived, but Colonel Trappes-Lomax decided to await further reinforcements, establishing in the meantime a defence position at Stien, on the road which skirts the fjord between Finneid and Mo. The other possibility, that the

--182--

Germans might cross from Hemnesberget to the north side of the Ranfjord to attack Mo from the west, was covered by the Norwegian reserve troops evacuated earlier from Mosjöen. Next day, the Germans had pushed so far across the peninsula that their mortars and heavy machine guns commanded the road to Finneid, along which the Norwegians who had made the detour from Elsfjord would have to pass. A counter-attack was therefore launched which enabled the Norwegians to pass through, but on the 14th the Germans pressed forward again, and that evening, after some serious fighting, No. 1 Independent Company and the Norwegians abandoned Finneid and retired through the position at Stien.

By this time Brigadier Fraser, who received instructions from General Mackesy's successor, General Auchinleck,7 to maintain an advanced detachment at Mo as long as possible, was on his way down to view the situation. Having conferred with Lieut.-Colonel Trappes-Lomax and the newly appointed Norwegian area commander, Lieut.-Colonel R. Roscher Nielsen, he formed the view that the position in the Mo area was untenable. In the first place, the Navy could not maintain an adequate flow of reinforcements and supplies because of the air threat. Then there was no good alternative route of communication overland, since the road north from Mo to Bodö was a mountain road climbing well above the snow line; this could be dominated by the German air force, which was already reaching as far afield as Bodö. Moreover, Colonel Trappes-Lomax said that in any case he required another battalion if he was to hold Mo against serious attack. The Germans, on the other hand, were increasing their strength daily. Hemnesberget was being reinforced and supplied by seaplane. A German battalion was already using horse-drawn transport to make the difficult mountain crossing (which the thaw might soon render temporarily impassable) to Korgen from a point near Elsfjord, where the ferry and possible substitutes had been withdrawn to delay them. Other German columns were reported north of Mosjöen. They had not yet been identified as troops of the 2nd Mountain Division under General Feurstein, which had been diverted from the impending attack in Western Europe and shipped to Trondheim as an additional division by the Fuhrer's orders with a special mission to penetrate at top speed towards Narvik[10]; they now totalled five mountain infantry battalions and at least three troops of mountain artillery.[11] The German progress, however, gave sufficient indication that we had more than scouting parties to contend with.

But the importance of holding on was evident both to Lord Cork and to General Auchinleck, while at the same time the Norwegian Commander-in-Chief, General Ruge, and the Divisional General

--183--

Fleischer were renewing their representations that a further withdrawal would be disastrous. Particular importance was attached to the existence of a partly developed airfield site at Rösvik, ten miles north-east of Mo, though the Germans did not in the sequel appear to use this site (or Hattfjelldal) for the current operations. Thus on the very day (15th May) on which Brigadier Fraser reported that to continue to hold Mo was militarily unsound, Lord Cork was informing the Admiralty of his feeling that we must hold on and fight at Mo, since otherwise the whole Narvik situation would become precarious. There was also, no doubt, the unvoiced consideration of British prestige at stake. As Mr Churchill had minuted about the position at Mosjöen, many miles farther south, only eleven days earlier: 'It would be a disgrace if the Germans made themselves masters of the whole of this stretch of the Norwegian coast with practically no opposition from us and in the course of the next few weeks or even days.'[12]

The position at Mo, already difficult, was fated to be made worse by two disasters occurring in quick succession at sea. It was decided on the 14th that the Irish Guards, who sailed that day for Bodö, should be followed by our one remaining battalion, the 2nd South Wales Borderers. But shortly after midnight of 14th/15th May the Polish liner Chrobry, with Brigade Headquarters, 1st Irish Guards, and some other troops on board, was attacked from the air as she left the seaward extremity of the Lofoten Islands to steer across the Vestfjord. The Guards colonel, all three majors, and two junior officers were killed or mortally injured by the bombs as they slept. Fire broke out immediately amidships and most of the men were isolated in the fore-part where they could not lower the boats. While stacked ammunition ignited and the fire spread, so that the final explosion could be expected at any moment, the Irish Guards formed up on deck, with arms and kit, as on parade. Search parties dragged the injured from the blazing wreckage; the rest waited in their lines in the cold twilight; their chaplain began to recite the Rosary. The commander of the escorting destroyer Wolverine, which hastened to the rescue, while the sloop Stork warded off further attack, compares their discipline, which enabled him to trans-ship 694 men in sixteen minutes, to the conduct of the soldiers in the Birkenhead. The troops had, however, to return to Harstad to refit, and for the rest of the campaign their Commanding Officer was a captain.8 Much of the equipment lost was irreplaceable: it included three light tanks belonging to the 3rd Hussars, which were the only British tanks landed in Norway and had originally been destined for Mosjöen. Then on the evening of the 17th the cruiser Effingham, carrying

--184--

Brigade Headquarters and the South Wales Borderers to the same destination, after taking an unusual route outside the Leads to lessen the risk of air attack, together with a destroyer ran aground at twenty knots on the Faksen shoal within a dozen miles of Bodö.[13] One of the escorting anti-aircraft cruisers brought the troops back to the Harstad area, but there was again a serious loss of stores, including machinegun carriers. Attempts to refloat the Effingham failed. The expected attack on Mo had begun six hours before; our reinforcements would now be belated and under-equipped.

Action at Stien 17th/18th May 1940On the afternoon of 17th May, the Germans moved forward from Finneid, where they had built up a force of about 1,750 men, against the Scots Guards' positions. The latter had two companies at Stien itself, where the small river Dalselva debouches into the fjord, and their third company and the Independent Company (which was under their command) placed farther back on the road towards Mo. The four 25-pounders were also sited in the rear, but had little effect owing to the destruction of their communications which ran along the road. Serious fighting began about 6.30 p.m., and although the enemy brought a field gun into action from the high ground across the river and also covered the forward slopes of our position with machine-gun fire, the frontal assault along the road, which is fully exposed as it turns inward to the river-bridge, was firmly held. The

--185--

Germans suffered a good many casualties at the bridge itself, which they tried to restore with planks, but they made their main thrust down the river valley, which they had approached over the snowbound mountains from a point south of Finneid, collecting skis from farms as they went. Our forces had not been posted on the heights, in spite of warning, and three small Norwegian ski detachments which were supposed to watch the flank did little. The Germans also dropped paratroops on the mountainside nearer Mo, who developed a subsidiary flank attack at Lundenget. Along the Dalselva valley the fight continued through the short twilit night, with the Germans making full use of their tommy guns as they pressed along the north side of the valley towards the road, until at about 2 a.m. the Scots Guards were forced to fall back through the reserve position near Lundenget, where their third company still guarded the road to Mo.

Brigadier Gubbins had arrived on the scene during the night, having been appointed with acting rank to command the troops in the Bodö-Mo area in place of Brigadier Fraser, who had returned to Harstad to report and was then invalided home.9 After a telephone conversation with General Auchinleck the new commander gave orders for the retirement to continue to the north of Mo. The information was conveyed to the Norwegians by Colonel Trappes-Lomax, who said that he had been outflanked by superior German forces and had lost two companies. This had reference to the fact that, in addition to some seventy casualties suffered during the fighting of the previous day, there was a presumed loss of the entire rear company, which by morning held the point on the road nearest to the oncoming enemy, and was cut off before the instruction to retire farther came through. Brigadier Gubbins's orders provided opportunity for the Norwegians to withdraw first, using nearly all the available civilian transport, and their Divisional Headquarters agreed. At 3 p.m. the two bridges over the River Rana at the north side of the town were blown. Within the next half-hour the enemy entered into possession of Mo i Rana, marking the second main stage in their advance towards Bodö.

The geographical conditions of the area between Mo and Bodö made serious delaying actions—to say nothing of a counter-offensive—very difficult in face of enemy air power. Unfortunately, too, the decrease in the distance separating our forward troops from the base at Bodö did not mean a proportionate increase in the ease of reinforcement—though Bodö was at any rate a sizeable county town, provided with a concrete steamship-quay and four substantial wharves. As already related, a company of Scots Guards had been

--186--

sent there on 30th April, followed at intervals by two Independent Companies direct from home and the two that were evacuated from Mosjöen. Early on 10th May, just before that evacuation, an Admiralty telegram advised Lord Cork, only three days after all operations to the southward had been placed under the Narvik command, that it was essential to hold Bodö pending a full examination of the problem involved, and that, if necessary, the garrison must be reinforced from the resources at his disposal. Hence the diversion of all British troops from the Narvik area to serve under Brigadier Fraser and the orders which were given him, to hold Mo if he could but to 'deny the area Bodö-Saltdal permanently to the enemy'.[14]

The double misfortune which befell the transportation to Bodö has already been related. The result was that both the South Wales Borderers and the Irish Guards reached the Bodö area by detachments in destroyers and Puffers and they were not beginning to arrive there until the 20th. Therefore, although the Bodö Command, as we shall see, sent what it could, the withdrawal north of Mo must be considered substantially as a self-contained operation. A Norwegian machine-gun company and other very small Norwegian units accompanied the force, which was joined in the course of the first day by a fresh company of the Scots Guards, brought forward by motor transport across the mountain plateau from its position east of Bodö, and next afternoon by the missing company. After being encircled south of Mo, they had extricated themselves by an arduous crosscountry march over hills deep in snow to Storfosshei on the River Rana and had lost only four men in doing it.

The first part of the long route to be traversed follows the valley of the Rana in a generally north-easterly direction for fifty-five miles. It then descends again by a second valley system in a more northerly direction to where the Saltdal debouches into the fjords leading out to Bodö. The distance from the watershed to Rognan on the Saltdalsfjord is about forty-five miles, making about a hundred miles in all. Population is very thin even in the lowest reaches of the respective valleys; the barrenness of the mountain plateau between may be imagined from the fact that it lies within the Arctic Circle and includes a belt of perpetual snow. The German advance was not, at first, pressed hard: the demolition of the bridges imposed a serious obstacle, and the speed with which Mo had come into their hands had probably something of the effect of a windfall. Thus the British force (less the Independent Company, which was carried straight through to Rognan) was able to spend the second day after its withdrawal from Mo resting about thirty-two miles from the town in a position covered by the freshly arrived company at Messingsletten bridge. At this juncture Colonel Trappes-Lomax received

--187--

orders from General Auchinleck, saying: 'You have now reached good position for defence. Essential to stand and fight...I rely on Scots Guards to stop the enemy'.[15] The Colonel maintained, however, that it would be throwing away the only battalion available for immediate defence if a major stand were attempted before his men were safely across the vulnerable area of the snow belt, beginning about twenty miles up the valley. After reference to General Headquarters by telephone, Brigadier Gubbins issued modified instructions for 'hitting hard' and withdrawing only if there was 'serious danger to the safety' of the force.[16]

By midnight three defence lines had been manned, where the wide and rather featureless floor of the upland valley seemed most suitable. The enemy did not attack in earnest until the evening of the next day (21st May), when they outflanked our first line and followed up as far as the main position at Krokstrand, where the road crosses the river and a demolished bridge was defensible from good cover on the far side. But this likewise was held only for a few hours, until the Germans were able to enfilade it from higher ground on their side of the river, while it was also being machine-gunned from the air. It took the enemy (whose force included two bridging columns) one day to build a new bridge here in the wilds, and the British troops were not seriously pressed in their withdrawal to their third position, from which they moved in small parties that evening across the plateau, where the road for twenty-three miles ran between steep walls of snow. Three Bren carriers which had been salvaged from H.M.S. Effingham successfully screened the embussing. Thus the attempt to stop the enemy in what General Auchinleck called 'the narrow defile north of Mo'10 had been abandoned. As in so many other instances, German air supremacy played a large part—not so much in the actual assault on our positions, but in providing unhampered reconnaissance of our movements and in restricting within the narrowest limits the use of our lines of communication back to Bodö.

In the early hours of 23rd May a new position was taken up at Viskiskoia, where the road crosses to the east bank of the river, as it descends towards the Saltdal. The Scots Guards were deployed to cover the demolished bridge, while No. 3 Independent Company, which had marched up from Rognan, supported by a few Norwegian ski troops, was posted on the far side, high up and well in front, to deter the enemy from a flank advance. The German ground forces came up the following afternoon, supported by low-flying attacks from a single aircraft and by mortar fire. Two of our Bofors guns were out of action; the Scots Guards had only one 3-inch mortar left (which did some damage); and the field guns could give only very limited support on account of the loss of their signalling equipment

--188--

By 4 p.m. the Independent Company had been driven back, so that our main position was enfiladed. At 6, Brigadier Gubbins gave the order for another retirement to Major Graham, Scots Guards, who had succeeded to the command of the battalion on the sudden recall of their lieutenant-colonel to Harstad. Five miles farther on there was another bridge at Storjord, where it was planned to fight an action with much the same dispositions as at Viskiskoia. However,the Germans did not make contact until the evening of the 24th, when orders had just been received for the force to withdraw without further delaying actions, as fresh troops had now taken up position fourteen miles in their rear. Accordingly, the Scots Guards and other units continued down the valley, and in the course of the next morning they reached the Bodö area by boat from Rognan, where a flotilla of Puffers had just been assembled under British naval command.

The situation as viewed by General Auchinleck was that the Germans now had about 4,000 men with tanks and artillery in the Mo-Mosjöen area. He also knew that the vigour of their advance was enormously aided by control of the air, which we had as yet been unable to challenge. The policy therefore was to strengthen our ground forces for the defence of Bodö by all means within our power—it was even intended to add a battalion of French Chasseurs Alpins besides three more Independent Companies from England. Help was also sought from the Fleet Air Arm, while the landing ground at Bodö was being hurriedly prepared for aircraft to be transferred from Bardufoss. Already available in the Bodö area were the 1st Irish Guards, 2nd South Wales Borderers, less two companies, and four of the Independent Companies. The new position at Pothus was, therefore, manned in considerable strength, though Brigadier Gubbins, hampered by lack of transport, kept about half his troops strung out along the lines of communication to Bodö in anticipation of a turning movement from the sea or air. The action at Pothus was intended at least to give time to complete our preparations to repel the Germans finally at the approaches to the Bodö peninsula.

The hamlet of Pothus is only ten miles from the mouth of the Saltdal, and stands on both banks of the river, which by this point reaches a considerable size. As a defensive position, its leading features were the two bridges, a substantial girder bridge which carried the main road from the east to the west bank and a smaller structure crossing a tributary that flows into the Saltdal from the east a few hundred yards farther down-stream. A platoon (fifty-five men) of No. 2 Independent Company was concentrated here first. The battalion of Irish Guards and No. 3 Independent Company followed them and had completed their dispositions by midnight on 24th May, at which time the Scots Guards marched wearily through and went

--189--

Action at Pothus 25th May 1940out of the line. The Norwegians had sent forward two mortars and some patrol troops additional to their machine-gun company already posted with the rear-guard. There was now a clear sky by day and virtually no night, so that enemy air activity reaped the fullest benefit in reconnaissance and in attack—a fact which must be, weighed against the natural strength of the new position. The platoon and the support section (with a 3-inch mortar) belonging to No. 2 Independent Company held outpost positions on the west and east sides of the Saltdal respectively. The Irish Guards had their No. 1 Company strongly placed on a steep ridge beside the main road on the east side a little in front of the girder bridge (which was blown up prematurely and imperfectly in the small hours of the morning). Their No. 4 Company covered the bridge from the west side, with No. 3 behind them covering the main road and the river banks below the bridge. A reserve position, rather more than a mile back, was occupied by the last company of the Irish Guards and No. 3 Independent Company, and had the prospect of further reinforcement from the remainder of No. 2 Independent Company coming south towards the scene of action. The Norwegians were used in support of the British, with their mortar detachment placed on the high ground to the west of the British positions in rear of the road bridge, while the main road was further covered by our own single troop of artillery, which had been in the withdrawal from Mo. The headquarters of Stockforce—from now on the field operations in the Bodö area were commanded under Brigadier Gubbins by Lieut.-Colonel H. C.

--190--

Stockwell, formerly O.C. No. 2 Independent Company—were near the reserve position, hidden in a wood to the west of the road.

Enemy cyclists made contact with the outpost position along the main road on the east side of the Saltdal at 8 a.m. on 25th May. By 11 a.m. the support section had been driven in on the principal position protecting the girder bridge, where the Guards in slit trenches held the ridge firmly with the help of cross-fire from the field guns and the Norwegian mortars on the other bank. In the early afternoon, while five Heinkel aircraft were machine-gunning to create a diversion on the far side, the Germans tried to storm the ridge. They were driven back, but then proceeded gradually to outflank the position, by which means they eventually forced its defenders to withdraw. The last platoon to move back found that the bridge on the flooded side-river had been blown up and had to cross under fire by a hand-line improvised from rifle slings. The men from the ridge then made their way along a track down the Saltdal to a hanging foot-bridge about a mile below our reserve position on the other side. Meanwhile No. 4 Company, Irish Guards, posted immediately behind the main road bridge came under heavy fire, but with the help of Norwegian troops prevented any enemy advance across the river on to the west bank and inflicted considerable casualties. Headquarters, which had been burnt out by incendiary bullets in one of the air attacks, learnt of our reverse on the east bank about 6 p.m. and sent the reserves-No. 2 Company, Irish Guards, and No. 3 Independent Company-across the river to hold positions on and near a high shelf protected by cliffs at the northern angle of the river junction. These were occupied by 4.30 a.m. on the 26th and made the situation on our left flank reasonably secure.

During the night, however, the enemy had built a floating bridge a little higher up the river, so as to transfer the weight of the attack to the other flank. Our outpost on the hillside was forced to fall back towards the position still held by the Guards, preventing access to the wrecked girder bridge; and thereupon our only remaining reserve, a portion of No. 2 Independent Company, was sent up on to the hill in the forlorn hope of stemming the advance there and preventing our prospective encirclement. By 11 .30 the enemy were already pressing hard, and shortly afterwards Brigadier Gubbins at Rognan gave orders for a withdrawal; but it was not until mid-afternoon that Colonel Stockwell was able to concert this with his officers and it actually began at 7 p.m. No. 2 Independent Company was accordingly concentrated near the foot-bridge, where it occupied a covering position and engaged the enemy until 10.30 p.m. It was intended that the forces which had been posted to the east bank overnight should also withdraw to the foot-bridge, so as to occupy a rearguard position almost abreast of No. 2 Independent Company. The

--191--

order never reached No. 2 Company, Irish Guards. No. 3 Independent Company, whose position was more accessible, received the order but could not comply quickly enough. Instead of crossing by the foot-bridge, they continued their retreat down the east side of the Saltdal to its mouth, followed by the Guards company, when the latter heard of the withdrawal through a Norwegian liaison officer late in the evening. Meanwhile, No. 4 Company, Irish Guards, across the wrecked girder bridge, seized their chance to disengage when a Gladiator fighter appeared out of the blue and machinegunned their astonished opponents. The withdrawal down the road to the mouth of the valley at Rognan then proceeded according to plan, except for a party from Battalion Headquarters, who had been kept back to load the reserve ammunition on the last of the motor transport and were ambushed from a roadside farm afterwards as they marched. By this time the Germans were working their way down on to the road at many points. But at Rognan boats were available to ferry the force across the end of the Saltdalsfjord—a six-mile gap in the road which would hold up the advance of the enemy. This provided for the main body of troops which had been brought back down the road, and No. 3 Independent Company after its journey down the east bank made its way across the river to join them in time for the embarkation. But No. 2 Company, Irish Guards, unable to cross the river into Rognan, extricated themselves by means of a forced march of twenty arduous miles across steep and pathless mountains, arriving ultimately at Langset, where the road resumed at the other end of the ferry journey.

The only encouraging feature of the withdrawal was the presence (already referred to) of British aircraft, three Gladiators which had been sent from the newly-established air base at Bardufoss on the 26th. One of them unfortunately crashed on taking off from an improvised runway of wire-covered grass sods outside Bodö, but even two fighters patrolling by turns had a value quite beyond their immediate score of two German aircraft brought down and two more damaged. How far this new factor might have altered the whole trend of the campaign so far as the defence of Bodö is concerned it is impossible to calculate, since the remaining operations were governed by factors which had nothing to do with local conditions. On 25th May a destroyer from Harstad, carrying the last company of South Wales Borderers southwards, carried also a senior staff officer to concert plans for retirement with Brigadier Gubbins, who had already been warned by telephone of the Government's decision to evacuate North Norway. This decision, difficult enough in relation to the situation at Bodö, involved still harder problems farther north in relation to what had been achieved or was on the verge of achievement at Narvik.

--192--

Contents * Previous Chapter (XI) * Next Chapter (XIII)

Footnotes

1 The full name, used to distinguish it from a smaller 'Mo' farther south, which, however, plays no part in this history.

3 Despatch by Lieut.-General Massy, Part I, Sec. 8, Part II, Secs. 23, 28.

4 Getz, pp. 60, 99, 133.

6 Roscher Nielson, Major-General R.: Norges Krig, p. 427.

8 Fitzgerald, Major D. J. L.: History of the Irish Guards in the Second World War, Chapter IV

10 Despatch by Lord Cork: Appendix B, Sec. 32.