CHAPTER XIII

THE CAPTURE OF NARVIK[1]

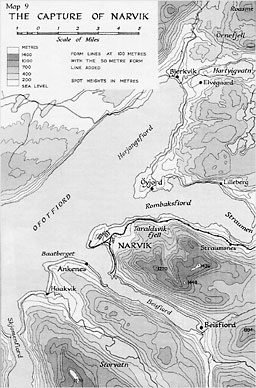

See Map 9, facing page 212

It will be recalled that the proposals for a direct assault on Narvik had died down temporarily after the naval bombardment of 24th April. But the first reliable signs of the long-awaited thaw encouraged Lord Cork, to quote the language of his official despatch, to 'look forward to the conduct of operations without the tremendous handicap of snow'.1 Accordingly, he had already made a further reconnaissance of Narvik in his flagship (1st May) when he received on the 3rd the imperative message from the First Lord of the Admiralty pressing for action 'even at severe cost'.2

The build-up of the Allied force was still in progress. The arrival of the Chasseurs Alpins was followed on 6th May by that of two battalions of the Foreign Legion, which had been formed in February in North Africa, where they were destined to serve again as a 'Free French' unit in 1942. Then, on the 9th, a Polish brigade of four battalions arrived, styled Chasseurs de Montagne. Their fighting qualities were still to be tested—a Pole who was in the brigade records that 'only a few of them had ever seen mountains at all'3—but their officers and non-commissioned officers had for the most part served in the Polish campaign and then escaped from Poland to raise the flag in France. The force had been created originally to utilise Polish anti-Russian feeling in connection with the abortive Allied expedition to Finland and had now been directed first to Tromsö; but the Norwegian authorities there were bitterly opposed to any suggestion that the Poles might help to garrison the extreme north of Norway, where the Russian attitude was thought to be uncertain. Allied artillery in the Narvik area now totalled 24 guns—a French group of 75's, which accompanied the Chasseurs Alpins, and twelve British 25-pounders. The gunners of 203 Field Battery, R.A., had arrived on 22nd April, the first of their guns with the landing craft a whole week later. Four of these were assault landing craft for infantry (A.L.C.s), the other four, shortly afterwards increased to six, were motor landing craft for material (M.L.C.s); the signal asking for them had been sent before General Mackesy left Scapa on 12th April. As for antiaircraft artillery, although a week of May had passed before the first

--193--

heavy battery was landed, the position at the beginning of the month was that three light batteries were also actually on the way to Norway, making a total of one heavy and four light batteries in all, and five more heavy and one more light battery were due to follow.

The naval force at Lord Cork's disposal had been increased after his arrival in Norwegian waters not only by a battleship (H.M.S. Resolution had now replaced Warspite in this role) but by the aircraft carrier Furious, which was likewise left behind when the Home Fleet returned to Scapa on 15th April. She worked in and out of the fjords as far north as Tromsö throughout the latter part of April, until she had only eight aircraft serviceable and her engines damaged by a near miss. Her place was, however, taken by the Ark Royal, and on 6th May the Scots Guards described her Skua fighters flying high over Harstad base as 'the first British aircraft that had been seen since our arrival in Norway—a very welcome sight'.[2] The number of cruisers was indeed reduced, particularly by the needs of the Aandalsnes and Namsos evacuations, but until the middle of May there were usually as many as fifteen destroyers available, indefatigable and ubiquitous. Thus German air attacks, though they sank the Polish destroyer Grom and did other damage, could not prevent the Navy from exercising a steady pressure against their forces in and around Narvik by its constant patrolling of the fjords.

The size and condition of the German force defending Narvik remained an open question. General Dietl's Mountain Division, which had been brought in by destroyers, could be estimated fairly accurately at 2,000 men, presumably doubled from the destroyer crews, but we did not know what losses they had sustained from the hard conditions as well as from naval bombardment and other fighting on an extended front. It was guessed at the time that a trickle of reinforcements, chiefly technical troops, was being brought in to Narvik by the railway from Sweden—it was scarcely within the power of the Swedes to refuse facilities for civilians, alleged Red Cross workers, etc., analogous to the facilities they had granted to volunteers for the Finnish war.[3] What quantities of supplies were also being brought in by the same route was uncertain. The main consideration, however, was the air lift. Seaplanes were eventually ousted from the Rombaksfjord, but they could alight in Narvik harbour and the Beisfjord at will; and pending the establishment of our own fighter aircraft we could not interfere at all with parachute deliveries, which were to be observed first near Bjerkvik and then high up on Björnfjell as a daily operation whenever the weather permitted. The cessation of hostilities in Central Norway, which was clearly seen to portend a big development in the enemy bomber offensive in the North, was expected also to make it relatively easy for the Germans to build up their infantry strength by air at Narvik.

--194--

The arrangements which they actually made at this juncture were as follows. On the termination of the campaign in the south, Army Group XXI was instructed to send one division home to Germany—this move apparently was not even started—and at the same time received back direct control of General Dietl's force, which had been placed under the Supreme Command (O.K.W.) since 15th April. The directive now given to Group XXI was that 'In co-operation with Air Fleet 5 every available means are to be used to get supplies to it [sc. Dietl's force] as quickly as possible'.[4] A further order, emphasising the importance of supporting the troops at Narvik, was issued by Hitler himself direct to the new air command formed for Norway under Colonel-General Stumpff, who had taken up his post in Oslo about the beginning of the month. There was a big increase in bomber attacks from a force of nearly 200 bomber aircraft now based on Trondheim. Paratroops and mountain infantry were dropped on Björnfjell, with heavy and light machine guns, and on 20th May provision of men was given a temporary priority over ammunition. But the Germans experienced many difficulties. Although their resources of aircraft at this time seemed limitless in comparison with our own, they had not enough of the long-range Junkers 52s, which could carry only a ton at a time and were wanted also to supply the overland advance from the Trondheim area, quite apart from large-scale withdrawals for the forthcoming invasion of the Low Countries. There were questions of organisation and management which caused considerable friction among the enemy even in the later stages, when the air lift was being controlled from Oslo by telephone through Sweden: Air Force objections, for example, to the dropping of mountain infantry not trained as paratroops. Lastly, they were hampered by the weather—poor visibility restricting operations and the thaw complicating them, because supplies had to be dropped close to widely scattered troop positions so as to minimise portage through melting mountain snow.

The German supply arrangements were therefore on a hand-to-mouth basis throughout: not until mid-May did they even have enough pairs of skis to equip their transport columns.[5] The scale of reinforcement was likewise modest. When his troops were first cut off, Hitler proposed to send essential supplies and possibly key men into Narvik by submarine, but nothing came of this: during the first month of the siege the total of arrivals, which were by parachute, seaplane, and railway, was only about 300 men, the railway handling chiefly supplies. The air lift began in earnest on 14th May, and between that date and the end of the campaign there were a further 1,100 arrivals, rather more than half of which were of paratroops, the rest being of mountain infantry with a few artillerymen and other specialists.[6] But the besiegers had no means of estimating with any

--195--

exactness the effects of the air lift; and in any case the use made of this new and formidable technique might have been stepped up at any moment, which constituted an additional reason for aiming at the speedy liquidation of the German defence of Narvik.

In all the circumstances it does not seem surprising that Lord Cork issued orders on 3rd May for an attack on the 8th, to be launched from the sea or across Rombaksfjord 'as judged best'.[7] But General Mackesy had in effect rejected the latter alternative as regards the immediate future only five days before, when the newly arrived General Béthouart after a preliminary reconnaissance with Lord Cork had proposed to land on the Öyjord peninsula forthwith, so as to take Bjerkvik in the rear and then with the help of artillery cross the Rombaksfjord to Narvik. As we have seen,4 the Chasseurs Alpins were employed in the northern sector for an overland advance instead. General Mackesy accordingly now prepared an outline plan to land two British battalions direct from the sea on the north shore some three miles from the town. But the senior British Army officers other than the General, who could not be wholly unaware that he had been subordinated to the Admiral to secure a more aggressive policy coûte que coûte, made representations to Lord Cork against the proposed attack. Their main objections were the following: the shortage of A.L.C.s for the first landing; the need to supplement the available M.L.C.s by local craft and trawlers, which would restrict the area of attack to steeply shelving beaches—only three in number, small, and bordered by high rocks; the impossibility of effecting a surprise in perpetual daylight and without smoke shells; and the prospect of enemy air attack against men in open boats or ashore and unable to dig in. Some senior naval officers, including Lord Cork's principal staff officer, Captain L. E. H. Maund, concurred with the Army in desiring that the attack should be put off pending further preparation. On the night of 5th/6th May Lord Cork forwarded the military representations to London for consideration, but before the final reply of the Chiefs of Staff had reached him,5 he decided to postpone this operation until a new general arrived on the scene, adopting in the meantime a course of action proposed by General Mackesy. It is an interesting coincidence that on 6th May Dietl himself had for the first time independently contemplated evacuating his forces from Narvik.[8]

The alternative British plan was to invest Narvik more closely by landing on the shore of the Herjangsfjord north-east of the town, so as to mount artillery at Öyjord and move farther inland to cut the

--196--

railway near the frontier. This step in the campaign had been projected as early as 29th April to fit in with the British push towards Ankenes as well as the Norwegian-French advance in the Gratangen area; but it was not until 7th May that General Mackesy, though pressed (as we have seen) by the French command, decided that the time was ripe. A careful reconnaissance from the sea on the night of 7th/8th May disclosed no sign of life on the part of the enemy, and the terrain near Bjerkvik at the head of the fjord appeared not unsuitable for the operation. From this village it should be feasible to move southwards about eight miles along the fjord on to the tip of the peninsula at Öyjord.

The landing operation, in which the British Navy was to convey and give close support to a French force, was to be combined with a further attempt by the Norwegians and the French to press overland towards Bjerkvik from the Gratangen area. It was agreed that there should be a simultaneous advance by the Norwegian left wing up in the mountains. But the main operation was postponed by Lord Cork from the night of the 11th/12th until the following night, with the result that the Norwegian 6th Brigade on the left flank, unable to make a last-minute postponement, moved forward first. They had the support of a few miscellaneous Norwegian aircraft functioning as bombers, and succeeded in occupying a succession of heights which brought them forward in the course of two days' fighting to the north edge of the Kuberg plateau; this mountain massif, rising (at the Kobberfjell) to nearly 3,000 feet, is the dominant feature in the country east of the Bjerkvik-Öyjord shore line, from which it is about seven miles distant. One battalion of Germans was thus driven back or otherwise accounted for by the Norwegians, the tactical gain being considerable and the more meritorious because of the conditions under which the 6th Brigade operated. The depth of the snow on the mountains had been up to 6-9 feet, and on the extreme left the supplyline had a stretch of about ten miles over which no cart traffic was possible throughout the period of snow and thaw. Their brigade staff officer describes the nature of the advance as follows:

Our push forward right until Kuberg was taken had to be made through narrow valley passages between mountain tops of up to 3,000 feet. These tops dominated the valleys. The Germans made use of this, climbed up and established themselves on the summits, and in order to go forward we had to climb up after them and get at them there on top.6

The naval force for the landing assembled on the 12th near Ballangen, where it picked up the two battalions of the Foreign Legion. having already embarked five of the ten small tanks which

--197--

the French had brought with them. They sailed about g p.m., General Béthouart accompanying Lord Cork in the Effingham. The battleship Resolution and a second cruiser, the Aurora, would give weight to the bombardment. There were also five destroyers, one of which (the Havelock) had mounted a French mortar battery on the forecastle. The foremost landing party of 120 men made the twenty-mile passage to Bjerkvik in the four assault landing craft; the rest of the 1,500 infantry mainly in the two cruisers, each of which drew a ready-made-up 'tow', consisting of a power boat and two pulling boats, behind her. The tanks were carried in the battleship, together with two motor landing craft for putting them ashore; a third, which was of a more modern type, went under its own steam. The whole was to be covered by aircraft from the Ark Royal. The original plan had provided that there should be no preliminary bombardment if there was a possibility of surprise, but in the end the leading destroyers had orders to open fire as soon as they reached their stations off Bjerkvik.

This bombardment began punctually at midnight—broad day in the latitude of Narvik but dark enough at Trondheim, it was hoped, to impede the German air force from flying to the rescue. It was timed to last a quarter of an hour, during which houses were set ablaze and ammunition stores exploded; but as the Germans kept up machinegun fire a general bombardment followed, with the particular object of knocking out enemy machine-gun posts on the foreshore, in houses, and in the woods behind. At one o'clock, when the landing commenced, the ships moved their barrage of fire inland. At two o'clock it ceased temporarily, but was reopened an hour or so later to fire overhead in order to cover the second landing. This completed the naval operations in the main, the big ships departing as the last troops left them, though some of the destroyers remained off Bjerkvik to give any further help. Such help was now less likely to be needed, as the aircraft of the Ark Royal, at first grounded by low cloud, began their fighter patrol for the landing about 2 a.m. and were later available to bomb objectives on the railway. No German aircraft put in an appearance. As for the main task of the naval force during the landing, it is difficult to estimate the precise effect of the bombardment: some part of an uncertain number of enemy machine-gun posts remained in action, but the troops at no time found opposition really heavy. British field ambulances helped to bring the French wounded to an improvised hospital ship.

The intended order of landing was: tanks—the first party of 120 men from A.L.C.s—other men from ships' boats. But the hoisting-out from the Resolution took so long that the more modern M.L.C. put her tank ashore independently, and this gave the signal to the men in the A.L.C.s. Two more tanks struggled ashore at the same time as the 'tows' were bringing in the rest of the first battalion; the

--198--

two remaining tanks came in with the second battalion. Nevertheless, it was the tanks which silenced the enemy machine guns. An officer of the Legion describes them as 'frisking about like young puppies, firing all the time, in the midst of fields which were here free from snow'.7 The first battalion had to land half a mile to the west of the village, but the tanks enabled it to make its way eastwards quite rapidly, and to advance from the village up the road north towards Gratangen. Meanwhile the other battalion had found the opposition from machine-guns in the Elvegaard direction too strong for a landing, so came ashore on the south-east side of the village about three furlongs from it. They were landing on the road to Öyjord, and their nearer objective, the former regimental depot at Elvegaard, was on the same side of Bjerkvik. Supported by their tanks, the French stormed Elvegaard building by building and captured a hundred machine guns and other material. Nevertheless, General Béthouart during the assault sent for two companies of the 2nd Polish Battalion as reinforcements. Destroyers went to fetch them from the Bogen inlet; but the battalion, whose orders were to press against the German patrols in that area, had set out overnight with no transport through the snow, and marched fifteen miles to the scene of action. When they arrived, victory was already complete. In the course of the morning the motor-cyclist section of the Foreign Legion arrived in Öyjord, where they found no enemy but their general and his staff, who had landed from the Havelock, which was supporting the patrol from the fjord. So ended, with only 36 casualties, the first of the opposed landings on which Allied fortunes in the later war years were so largely to depend and our first experiment in war with the landing craft which proved to be one of the main instruments of victory.

Unfortunately, however, it was not until 1.45 p.m. on the following day (14th May) that the troops from Bjerkvik were able to make contact with the right wing of the advance from the north, where the Chasseurs Alpins were due to clear the line of the Gratangen-Bjerkvik road. These now had the support of a battery of British anti-aircraft guns as well as of their own field artillery, and the 14th Battalion by the end of the day had reached a position commanding the first steep descent towards Bjerkvik. But the 6th Battalion, who had to move forward from mountain to mountain on the east of the road, stuck fast on the exposed slope between Roasme and Örnefjell and were unable to link up with the Norwegians on their left, so the enemy managed to withdraw to the south-east before the trap closed. Thus the Germans on the northern side of Narvik, though their position was greatly worsened by the successful landing, still held two fronts meeting in a right angle at the Hartvigvatn—a northern front against

--199--

the Norwegians up in the mountains, and a western front inland from the Bjerkvik-Öyjord road. The key to the position was the Kuberg plateau.

South of Narvik, the fighting had continued in the Ankenes peninsula, where the Officer Commanding 2nd South Wales Borderers was now operating with his own battalion and a battalion of Chasseurs Alpins, plus one company of Irish Guards in the rear at Haakvik.8 The French held about two-thirds of the line, including the snowbound ridge to the east, the British the area nearest Ankenes, from which our field guns could fire across the Beisfjord. But on the 14th, to complete the general policy of moving British troops to the Bodö area, arrangements were made to bring the South Wales Borderers away from the Ankenes peninsula, from which the company of Irish Guards and Brigade Advanced Headquarters had already been withdrawn. When this relief was carried out by the 2nd Polish Battalion, ferried over from Öyjord at 11 a.m. on the 16th, British soldiers (apart from the artillery, especially anti-aircraft artillery, and ancillary services) ceased to play any direct part in the siege of Narvik.

These arrangements to hold up the Germans in the south were instituted, under the general authority of Lord Cork, by MajorGeneral Mackesy, but carried out by his successor, Lieut.-General C. J. E. Auchinleck. General Mackesy's last operational instruction placed all British troops except the South Wales Borderers under command of Brigadier Fraser for operations in the Mo area. This was issued on 11th May, after Lord Cork had left in the Effingham for the scene of action at Bjerkvik; General Auchinleck arrived from England, had a brief meeting with Major-General Mackesy, and joined Lord Cork on board the flagship the same day. He then accompanied the Admiral on a preliminary reconnaissance of Narvik, where he noted that 'information as to the enemy strength and dispositions is practically non-existent and appears unobtainable',[9] and witnessed the events of the landing at Bjerkvik. His instructions from the Secretary of State for War had been signed on 5th May, by which date his coming was known to both commanders in the field.9 He was appointed as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief Designate, to take independent command of the land forces and air component when Lord Cork's existing plans—meaning presumably his proposals for the assault on Narvik—had been either executed or abandoned. In the meantime General Auchinleck was to prepare a report on the needs of the situation. However, on the afternoon of the 13th, when

--200--

the Admiral and General returned to Harstad, a conference was held, of which the upshot was that General Auchinleck, exercising discretionary powers given him by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, assumed immediate command, under Lord Cork, of the land and air forces, to which the name of North-Western Expeditionary Force was now given.[10] At a further conference with General Bethouart at 10 o'clock next morning, General Auchinleck took the final decision to employ all the British land forces in the struggle farther south -these were the forces which defended the Mo-Bodö area as described in the last chapter-and to place General Bethouart in command of all land forces in the Narvik area. His recent success at Bjerkvik had underlined the fact that the Frenchman was an expert in both mountain and winter warfare, who (like Dietl) had served a course in Norway before the war. Thus the assault on Narvik would be the direct concern of the French and Poles, in co-operation with the Norwegians, who readily agreed to transfer to General Bethouart': command for the period of the operation their most appropriate battalion, one largely recruited from the Narvik area. The plans were then prepared in concert with the British naval staff.

Meanwhile General Auchinleck had orders from the Chiefs of Staff to report in conjunction with Lord Cork as to the area to be held in North Norway and the means required to hold it. Collaboration was made easier by the transfer of the Admiral's headquarters to shore on 16th May, the date on which the General sent home the agreed report. He took as his starting-point the assumption that our first object, the denial to Germany of an iron-ore supply shipped through Narvik, had already been achieved by the destruction of the port facilities through our naval operations and the German demolitions. General Auchinleck further assumed that our position vis-à-vis the Swedes rendered any attempt to interfere with the iron-ore route through Lulea impracticable. Therefore he had only to plan for the maintenance of the integrity of North Norway. The General concluded that Bodö must be held permanently to defend Narvik: hence the troop movements already described. Secondly, a tentative project for a military base at Skaanland was found impracticable, and Tromsö selected as an additional base and a hospital base (for 1,200 beds). The headquarters of the Norwegian Government was already located there. The Tromsö project was to involve an additional demand for anti-aircraft defences to secure the assent of the Norwegian authorities, who were particularly apprehensive about air attacks because of the nearness of Russian territory, from which they thought the Germans might operate. An advance base party left Harstad for Tromsö on 23rd May, and four anti-aircraft guns were duly set up there, marking incidentally the farthest northward stretch of our military power in Europe.

--201--

As regards the defence requirements of the area as a whole, General Auchinleck's report proposed a nucleus of four cruisers and six destroyers for naval defence, a military force based on seventeen infantry battalions, 200 anti-aircraft guns (thirteen heavy and eight light batteries), seven batteries of field artillery and howitzers, some armoured troops, and an air force of four squadrons. But the details thus set out read ironically in view of the desperate position already taking shape in northern France. On the 17th the Chiefs of Staff telegraphed, stating that the size of the force must be severely limited and asking for the General's views as to the retention of Narvik under the new conditions. General Auchinleck on the 21st returned a reasoned answer, pointing out, for example, that in the case of antiaircraft artillery he was being asked to make do with less than one-half of his estimate of his needs, which in turn was only two-thirds of the estimate prepared by the War Office before he left London. He concluded as follows:

The inevitability of the evacuation of Northern Norway in the circumstances envisaged in your telegram is, in my opinion, entirely dependent on the enemy's will to avail himself of his undoubted ability to attack. Should he attack I cannot, with the reduced forces suggested by you, hold myself responsible for the safety of this Force, nor will I pretend that there is any reasonable certainty of my being able to achieve the object given to me in my Instructions. If, in spite of this, larger considerations lead His Majesty's Government to decide that Northern Norway must continue to be held with the diminished resources laid down by them, I cannot answer for the consequences, but you may rest assured that every effort will be made to do what is possible with the resources at my disposal.[11]

The inadequacy of the force at its disposal, actual and prospective, was not the only difficulty confronting the British Supreme Command. General Auchinleck's arrival in North Norway had been closely followed by that of Colonel R. C. G. Pollock as head of a military mission to the Norwegian Government, which was intended to reduce friction and misunderstanding. Unfortunately, the situation was too unmanageable. The King and Government, to whose respective seats in Maalselvdal (north-east of Bardufoss) and round Tromsö Lord Cork paid formal visits on 23rd May, had transferred executive responsibility for defence to General Ruge as head of a Supreme Defence Command, situated in Maalselvdal and staffed mainly from the entourage which had accompanied him as a Supreme Military Headquarters from Gudbrandsdal. It was, for instance, General Ruge who initialled the agreement for a British base of severely circumscribed extent at Tromsö,[12] and the intention was gradually to transfer all such negotiations to his charge, leaving General Fleischer free to devote himself entirely to the operations of

--202--

his Division. This might have made for more harmonious relations with the Allies in the long run, but the short run was beset with difficulties, and General Ruge continued to press for the appointment of a new military attaché in place of Lieut.-Colonel King-Salter,10 so as to have a separate channel of communication with the British military authorities at home.[13] One of General Auchinleck's first actions was to arrange a conference with Generals Ruge and Fleischer at Harstad, when he found them 'both anxious to help apparently';[14] but the clouds of suspicion were not dispelled.

The Norwegian generals tended naturally enough to interpret every British action in the light of the recent abandonment of Central Norway and the current retreat on Bodö. They were also extremely sensitive to any interference with civilian liberties or property in the battle area, such control being their prerogative even if they did not choose to exercise it. Our reticence regarding operational movements again provided many unintentional slights. But what was perhaps most hampering to good mutual relations was the silent argument with which they were presented by the spectacle of our delays and apparent hesitations: ought there not to be a unified command in the hands of a general who understood the climate and the terrain? On 11th May General Ruge had proposed to Lord Cork that Lieut.-Colonel Roscher Nielsen11 should command the British troops in the Mo area 'in this present crisis'; he and his principal subordinates would have welcomed a similar solution in larger areas.[15] And in the background there was always the natural fear of divergent strategic interests, which made the Norwegian military leaders concerned even at this stage that they and not the Allies should provide the garrison of Narvik and the troops which would subsequently seize the key position on the Swedish frontier.[16]

But Narvik could not be garrisoned before it was recaptured, a task which had from the outset presupposed the assertion of British maritime power and was seen increasingly to require also the establishment of our air power. To this we must now turn.

The reconnaissance of the Narvik area had been carried out by Wing-Commander R. L. R. Atcherley at the end of April while the proposed air component, two fighter squadrons and one bomber squadron under the command of Group Captain M. Moore, was still being made ready. Banak, at the head of the Porsangerfjord, proved to be the only possible base for bombers. It had the advantage that it was not snow-bound, but the disadvantage that it lay two hundred miles north-east of Narvik. The distance might not prove

--203--

an insuperable obstacle to the operations of the aircraft concerned, but it involved a heavy drain on naval resources, which would have had to be stretched to protect seaborne communications round the North Cape. Banak was in fact never used, though Lord Cork and General Auchinleck urged persistently that without the help of at least one bomber squadron we could make no effective reply to the German offensive. One of the fighter squadrons was to be based on Bardufoss, fifty miles north of Narvik—a small Norwegian military airfield equipped with two short runways. The nearest point on the fjord for landing supplies was the little wooden jetty at Sörreisa, seventeen and a half miles away by a narrow lane requiring immediate reconstruction. The other squadron was to be based on Skaanland, south of Harstad, where a stretch of level ground was found which had been partially drained. In addition it was intended from the outset to develop a forward landing ground on a conveniently placed site just outside the town of Bodö.

The physical obstacles were enormous. The reconnaissance party found Bardufoss under four and a half feet of snow and Skaanland under two feet, though at sea-level; beneath this there was a layer of ice; beneath the ice a further penetration of frost deep into the soil. Snow clearance, blasting of ice, drainage of the site, and surface rolling had all to be taken in hand, while the spring thaw hindered as much as it helped because the melting heaps of snow flooded back on to the cleared area. There were also other obstacles raised, to begin with, by the Norwegian General Fleischer, who demanded a written promise from the R.A.F. that there would be no sudden withdrawal as from Aandalsnes and (more effectually) resisted the introduction of British or French troops at Bardufoss to clear the snow. Nevertheless, work began forthwith. At Bardufoss there was help from Norwegian airmen familiar with the site, from a local labour supply providing two ten-hour shifts of about 300 men each, and from a reserve battalion of General Fleischer's troops sent primarily for guard duties. A bulldozer was fortunately available, and the R.A.F. even stooped to conquer with a baggage train of two hundred mules. Bardufoss was eventually equipped with one runway, having a usable length of rather more than 800 yards and up to twenty camouflaged blastproof shelters for aircraft in the surrounding woodland, with convergent taxi-ing lanes which suggested the nickname of the Clock Golf Course. The second runway was cleared but its surface could not be made satisfactory, so work was begun on an extension of the first runway to 1,400 yards. A rudimentary operations room was constructed underground, and an extensive system of air-raid shelters was also gradually developed, which, together with the safe dispersal of aircraft, should go far to avert such a disaster as had befallen the Gladiators at Lesjaskog.

--204--

At Skaanland, however, in spite of a similar expenditure of effort the airfield never became fit for use and has since reverted to farm land. As for Bodö, the site there was crossed by two large ditches and a network of power and telephone lines; 176,000 grass sods had also to be cut to cover a section which had been ploughed; but there was no snow and plenty of labour in the neighbouring town. The Norwegian authorities had the field prepared in ten days in spite of air raids, which were probably precipitated by a broadcast appeal from the Chief of Police for five hundred men to report on the site. As we have already seen,12 it came into service on 26th May, and after the first trial the runway was relaid in fourteen hours with 900 feet of snowboards. But Bodö was then given up so quickly that the forward landing ground there plays little more part than Skaanland in the general story.

Bardufoss, therefore, had to be used without any alternative being available in the event of heavy attack; but it was not without defences. The field was equipped with eight heavy and twelve light anti-aircraft guns; and two lines of Observer Posts had been set up, which were all the more important because it was not found possible to establish radar stations in North Norway without further experiment. One such line was in the south from Bodö east to Fauske; the other covered the western approach through the Lofoten Islands. Unfortunately the pack wireless set supplied was far too weak to send messages across the high iron-bound mountains. It was still more unfortunate that our initial preparations were made in ignorance of the fact that the Norwegians had their own chain of Observer Posts, operated chiefly by women volunteers, which stretched down into enemy-held territory along the coast to a point south of Mosjöen. Nor did it make for smooth working that a force of six officers and 269 men (R.A.F. and Army combined) had been sent out on a task involving wide dispersion with no transport and no prearranged billets. However, by the time the first squadron arrived at Bardufoss the two observer screens between them were reporting enemy movements to Headquarters at Harstad with a delay of between two and ten minutes. Thus the air base got general warnings, but they depended upon the eyes and ears of the watchers and the efficiency of the telephone by which they were transmitted, and it was impossible to dispense with standing patrols all round the clock. Finally, there was a company of Chasseurs Alpins at the airfield to guard it against attack by paratroops.

As we have noticed, there had been a lull in German air activity the day of the Bjerkvik landing, but it was afterwards renewed more fiercely. In spite of the work of the Fleet Air Arm, which operated

--205--

some fighters from the Ark Royal until the 21st, more than a dozen ships were bombed within a fortnight; the most important were the battleship Resolution, which was sent home for safety on the 18th after a bomb had pierced three decks, the transport Chrobry (already referred to), and the anti-aircraft cruiser Curlew, lost with many of her crew on the 26th after innumerable attacks while protecting the construction of the Skaanland airfield. The headquarters of the French units had also been bombed on several occasions, and the 6th Chasseurs Alpins suffered serious losses on the 21st while moving into a reserve area. Thus it was clear that the further progress of the campaign must depend upon the provision of land-based fighter aircraft, the first of which took off for Bardufoss from the carrier Furious at 6 a.m. on May 21st, the day that she replaced the Ark Royal on the station.

They were the same Gladiator squadron, No. 263, which had made the ill-fated flight to Lesjaskog nearly a month earlier. The weather was again thick and foul, with the result that two aircraft were wrecked on the mountain side, but from the following morning patrols were maintained over the base and the fleet anchorage. The final assault on Narvik was timed for 28th May, to allow of a further strengthening of our position in the air by the arrival of the Hurricanes of No. 46 Squadron. They flew off from the Glorious on the 26th for the Skaanland airfield, which had that day been passed as fit for use, but three out of eleven aircraft tipped on to their noses on landing as a result of the soft surface of the runway. The Hurricane squadron had therefore to be diverted to Bardufoss, which meant that the Bodö area was at extreme range for them, and Gladiators (as already noted) went to Bodö in their stead. However, the air component had now reached its final strength, which may be computed at rather less than two-thirds of what had been requested: for there was no bomber squadron and the slower Gladiators had been substituted for one of the two squadrons of Hurricane fighters specified in the original Air Ministry project. The force also included a squadron of six naval Walrus amphibians, which arrived at Harstad on 18th May, but they were used more for transport than patrol work.

From 22nd May to 7th June there was no day without important activity in the air; the lowest total of sorties in twenty-four hours being ten in appalling weather, and the highest, flown on the day that Narvik fell, reaching ninety-five. The task set for the R.A.F. was not an easy one. The enemy's advance northwards made it increasingly possible for him to employ short-range aircraft, such as dive-bombers (fitted with extra petrol tanks) and twin-engined Messerschmitt fighters, whereas our own Gladiator fighters were actually slower than the regular Heinkel bombers. Moreover, our standing patrols-relays of aircraft continuously at work in all flying weather—

--206--

were exposed to heavy strain by the unusual terrain, as the mountains cut them off from communication with the ground and the narrow fjord valleys threw up dangerous air currents. Nevertheless, the Gladiator squadron claimed to have destroyed twenty-six enemy aircraft, the Hurricane eleven. This was a rate of loss which—even when we add in the 'bag' of the anti-aircraft batteries, computed to be twenty-three—the Germans at this stage in the war could easily accept, but our losses in action were less than one-third of theirs and the important fact is that the R.A.F. acquired a sufficient ascendancy to preserve the base areas and lines of communication from sharing the fate of Namsos and Aandalsnes. Otherwise, Narvik would have been much harder to take and impossible to hold.

The situation of the troops on the eve of the final assault—postponed by stages from 21st to 27th May, for reasons which included waiting for the M.L.C.s (busy with the transport of guns and stores for the airfields) and later for the Hurricanes—was as follows. The Norwegian 6th Brigade, continuing its separate struggle in the high mountains, had made two attacks against the German posts in the region of the Kuberg plateau, the second of which (on 22nd May) had been successful. Thus the Germans had been pressed back from any position which might threaten Allied control of the Öyjord peninsula. Moreover, the 14th Chasseurs Alpins, closely supported by warships, had been working eastwards along the shore of the Rombaksfjord and up on to the heights behind, where they joined hands with a part of the Norwegian 7th Brigade. The French were now based on Lilleberg and controlled the greater part of the road leading from there to the narrows at Straumen. Only the width of the Rombaksfjord separated them from the defenders of Narvik and the railway line, about 800 strong (including one new infantry company dropped by parachute and some sailors), with their headquarters in the northern outskirts of the town. On the south side of Narvik, beyond the Beisfjord, there had been a brisk German counter-attack with strong mortar support on the morning of 17th May, a few hours before the Chasseurs Alpins were due to be relieved by the Poles, who had the previous day relieved the British.13 This had been repelled with the help of the British field guns, left behind under French command, and the operations in this area then passed into the charge of the Polish General Bohusz-szyzko, with the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Polish battalions and a detachment of French ski troops. The Poles held most of the long ridge beside the Beisfjord, but at its bottom end German patrols of about 100 infantry and the pick of the sailors were

--207--

still ensconced in the mountains and threatened to outflank them at the Storvatn. At the other end of the Polish line, however, the western part of Ankenes village as far as the church was reported on the 24th to be clear of the enemy, though beyond this point (as we now know) they had about 200 men with mortars and machine guns deployed on a front of two miles.[17]

Accordingly, the final plan of attack envisaged an assault landing from Öyjord straight across the Rombaksfjord, a distance of about one mile, to a stony beach, behind which the side of the Taraldsvikfjell rose so steeply that every possible machine-gun post except one railway tunnel lay open to bombardment beforehand from the sea. Once established ashore, the troops were to move over the shoulder of the mountain south-westwards into Narvik. This operation would be synchronised with a double thrust by the Poles—against Ankenes and to the head of the Beisfjord. Meanwhile the French and Norwegians on the northern flank would keep up the pressure on the far side of the Rombaksfjord, leaving the Germans with only one way of retreat, namely the route along the railway through Sildvik towards the Swedish frontier. At that stage, if all went well, General Béthouart hoped to administer the coup de grâce by sending one company of the 3rd Polish Battalion (held in reserve at Ballangen) and the skiers of the Chasseurs Alpins across the mountains from the head of the Skjomenfjord14 to seize the railway in the Germans' rear.

The forces to be brought across the Rombaksfjord comprised the two battalions of the Foreign Legion, a Norwegian battalion as arranged, and a section of tanks. Only three assault and two motor landing craft remained, which automatically limited the first flight to 290 men. The next flight could not be brought across until threequarters of an hour later, so there would be a critical interval. Naval support available was much less powerful than it would have been had Narvik been attacked earlier. There was no capital ship, and only one ship with 6-inch guns, but a full table of objectives was arranged for a preliminary bombardment, to be directed particularly against the mouths of the railway tunnels and supposed machine-gun posts; this was timed to start twenty minutes before the first landing. Four destroyers were to bombard from the Rombaksfjord, while the anti-aircraft cruisers Cairo (the flagship) and Coventry with the destroyer Firedrake bombarded from the Ofotfjord. The Southampton with her 6-inch guns stood farther out, and had for additional targets the east end of Ankenes village and German embarkation points opposite. The sloop Stork was to protect the landing craft from air attack if necessary, but both our fighter squadrons were due to patrol the area throughout the operation.

--208--

The naval bombardment began at twenty minutes before midnight of 27th /28th May, and covered a wide enough area to conceal our intentions, while two batteries of French 75's and one Norwegian motorised battery posted behind Öyjord concentrated their fire upon the landing zone. Described in General Auchinleck's report as 'heavy and accurate'15 and by the Mayor from inside the town as 'one continuous explosion',16 the bombardment does not appear to have had much lasting effect upon German morale or armament. But under cover of it the landing was made punctually at midnight without loss or detection, and the Germans missed their chance in the first threequarters of an hour when the only support available came from the guns, which operated under the greatest difficulties, as the troops advanced through broken ground where the prearranged system of signalling by naval officers proved almost impossible to carry out.

In order to preserve surprise, the first flight had been embarked, in the three assault landing craft and two motor landing craft still surviving, from a position in Herjangsfjord which could not be observed from Narvik. The second flight was due to embark at Öyjord itself, which came under fire from a German field gun or mortar, so that it was necessary to bring the remoter position into use again. This not only delayed embarkation but reduced numbers from four sections to three, because the water there was too shallow for the use of Puffers in place of the M.L.C.s, which wcre now transporting the tanks. These last, two in number, were intended to lead the infantry advance towards the town, but they were bogged down on the landing beach (where one of them could still be seen in 1949). Nevertheless, by 4a.m. the first battalion of the Foreign Legion and the Norwegian battalion were both ashore. The Foreign Legionaries had then established their position on the lower slopes, through which the Norwegians began to clamber up, with the shoulder of the Taraldsvikfjell as their first objective. Once this was gained they could dominate the approach to Narvik, which lay to the west of them. To the east, along the line of the railway, they were protected by the naval bombardment of the railway station at Straumsnes and of the intervening tunnels.

The situation at this point was altered greatly to our disadvantage by a sea fog, reaching Bardufoss airfield about 4.15 a.m., which grounded our aircraft for some two hours but left the fjords farther south unfortunately clear. German dive-bombers then appeared on the scene. Two bombs hit the flagship, which lost thirty men killed and wounded, and the need to take constant evasive action reduced support of the troops on shore by naval gunfire to very little. General Béthouart, however, at this stage requested the assistance of only two destroyers, so about 6.30 a.m. the Admiral withdrew,

--209--

leaving the Coventry with the necessary destroyers to complete the Navy's task. Only one small craft, a Puffer loaded with ammunition, was lost to the landing forces through the bombing; but it had the important effect of delaying the arrival of the second battalion of the Foreign Legion, which did not complete the crossing until 11 a.m. German aircraft intervened again later in the morning against the Poles advancing on Ankenes, and there was yet a third attack on troops in the evening, when they nearly hit the Coventry; but after the fog cleared from Bardufoss continuous protection was provided by the R.A.F., which kept three aircraft patrolling over the battle area, made ninety-five sorties and fought three engagements during the day.

Meanwhile, the Germans made a determined counter-attack; this may have been encouraged by the factors mentioned above, but was probably based primarily on the possession of the higher ground along the Taraldsvikfjell. The Norwegians had reached but not secured a declivity which runs along the side of the hill about 900 feet up, making ambush possible, when the counter-attack came, delivered by a well-hidden party armed with hand grenades and some light mortars. The Norwegians and French were at first driven back across the railway down the steep hillside towards the beaches, one of which came under machine-gun fire, so that a new landing point had to be found for the second battalion of the Foreign Legion farther west. General Béthouart's Chief of Staff was among those killed on the beach. But with the help of a destroyer and the field guns firing from across the fjord, the officers rallied their troops and the situation was restored after a critical half-hour. The last enemy gun in a railway tunnel to the east was eventually silenced by the French manhandling one of their own small pieces up the precipitous slope from the shore. No further threat to the Allied landing developed, but the wilderness of rocks and scrub through which the Germans now withdrew along the railway lent itself to defence, so it was not until late afternoon that the Norwegians and the Legionaries of the 1st Battalion had finished clearing the hillside. Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion on the right flank occupied a knoll north-west of Narvik railway station, where General Fleischer, who had accompanied his own troops in the landing, now joined the French. The German garrison, having finally dwindled to a lieutenant and a hundred men, had escaped from the town about midday along the Beisfjord road.

This result depended partly upon the operations on the south side of the Beisfjord, where the Poles, with two battalions in the line, one in reserve, and the fourth protecting the rear at Ballangen, likewise launched their attack against Ankenes at midnight. Two French light tanks had been put ashore for their assistance, but were stopped by

--210--

mines. With the help of the naval bombardment and the British 25-pounders one company penetrated the village at the first onset, but in so doing exposed the right flank, against which the Germans at about 7 a.m. launched a serious counter-attack. Positions held since the first days of the landing in this area were forfeited for a time, but about noon the enemy began slowly to give way, as Polish pressure farther inland threatened to cut their line of retreat. The Poles secured the heights above Ankenes in time to sink the last boatload of sixty Germans escaping across the harbour, but more got away down the road on the north side of the Beisfjord. Meanwhile the other wing of the Polish force also met with stubborn resistance on the heights, but by early evening they were pushing across towards Beisfjord village at the head of the fjord, where they made contact with the motor-cyclist section of the Foreign Legion advancing by road from Narvik the same night.

Narvik itself, thanks to a characteristic act of courtesy on the part of the French, was entered first by the Norwegian battalion, who were followed under General Fleischer's instructions by a detachment of Norwegian military police. They went in at 5 p.m., the tiny vanguard of all the armies of European liberation; and the capture of the town and the Narvik promontory was officially reported by General Béthouart at ten that evening. The operation had resulted in a casualty list of about 150, of which the Norwegian losses were sixty; between 300 and 400 prisoners had been taken. Neither French nor Polish troops were billeted in Narvik, where heavy air raids were not unreasonably expected, and the fighting moved away to the east towards Sildvik, a distance from which the Germans could not easily launch a counter-attack. It had been decided at an earlier stage not to use Narvik as a base for military or naval purposes, and the ore traffic which had made it a centre of the world's interest for so many months seemed to be in any case at an end. After careful examination of the harbour, where twenty wrecks was 'a conservative estimate',[18] the burnt-out ore quays, destroyed ore-handling plant, and battered railway, the Chief Engineer of the Allied forces reported that ore could not be exported again in appreciable quantities within a period of less than a year. But none of these considerations was primarily responsible for the paradoxical situation that Narvik, once in our possession, had ceased to count.

--211--

--212--

Contents * Previous Chapter (XII) * Next Chapter (XIV)

Footnotes

1 Sec. II (5).

3 Zbyszewski, Karl: The Fight for Narvik, p. 3.

6 Norges Krig, p. 404.

7 Lapie, Captain B. O.: With the Foreign Legion at Narvik, p. 34.

14 Pronounced 'Showmenfure'.

15 Despatch by Lord Cork: Appendix B, Sec. 63.

16 Broch, p. 135.