By Ken Moore

One of my favorite native herbs, rabbit tobacco, is an eye-catching wildflower with an engaging aromatic quality. Frequently called sweet everlasting, among countless other names, it retains its wooly white stems and leaf undersides and aromatic qualities for months. Late in the season, the stem leaves turn grayish and take on a lasting curly, dried characteristic.

The ample late-summer rains have been good for this common annual of open fields and roadsides; I’ve enjoyed seeing more of it this year than in the past. And even now in late November, the aging tawny-white seed heads are evident along roadsides.

Its scientific name, Gnaphalium [naff-AY-lium] obtusifolium, from the Greek, gnaphalon, refers to the soft, wooly hairs on stem and leaves. The leaf, -folium, is obtuse, obtusi-, being somewhat rounded at the leaf tip. Now, just to keep some of you taxonomically current, I recently discovered that this plant has been reclassified to Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium.

I’m always intrigued by plants with pseudonyms. I guess rabbit tobacco is not really a gnaphalium, but it’s like a gnaphalium. I’ll leave it to you to ponder its taxonomy.

I’m more intrigued with the common name, the heritage of which I’ve yet to discover. One story is that some Native Americans believed rabbits liked this native herb and were helpful in caring for it in their field habitats.

I presented my question to revered Lumbee herbalist Mary Sue Locklear at the American Indian Heritage Celebration in Raleigh last Saturday. She replied that she had never read or heard a satisfactory explanation, though she enjoys imagining that the bunch of tiny white flower heads resemble the rabbit’s tail, and thus the name. I like her explanation.

She also said there’s nothing better for breaking fevers than a long steeped tea of equal parts dried rabbit tobacco leaves and flowers, green pine needles and green sweet gum leaves. Sweet gum leaves are collected green and dried for use during the winter months.

Earlier Saturday morning at the Carrboro Farmers’ Market, I visited with local herbalist, wildcrafter and teacher Will Endres. Like so many of us, Will also was puzzled about the heritage of the common name; he considers the name a bit demeaning for an herb of such great value. As a digestive bitter, chewing the green leaves is one of nature’s finest herbal aids. Will prefers to use the green leaves.

When asked about smoking rabbit tobacco, Will had a lot to describe. He said it does relieve symptoms of asthma and similar respiratory ailments. He prepares a rabbit tobacco mixture, with other herbs, that is helpful for folks trying to break a smoking habit.

I could have talked with Will Endres and Mary Locklear all day without exhausting the medicinal, ceremonial and spiritual heritage of this engaging plant.

And as for those rabbits – well now, Peter Rabbit was known to enjoy rabbit tobacco tea, though it was most likely a lavender substitute, perhaps the very first “pseudognaphalium.†And then there was Uncle Remus’ Brer Rabbit who “tuck a big char terbacker … you know this life everlastin’ that Miss Sally puts among the clothes in the trunk; well, that’s rabbit terbacker!â€

Apple-size fruit of Japanese persimmon are larger but not tastier than native persimmon. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

Several weeks ago, I was quizzed by a Citizen reader about a particularly dramatic small tree in a Carrboro yard along his daily route near the intersection of Hillsborough and North Greensboro streets. He described it as a small tree having orange miniature pumpkin-like fruits. I had to pause and think for a short while. “Oh, yes, I remember there is a small tree in that neighborhood that appears festooned with lots of little jack-o’-lanterns.â€

It’s one of those eye-catching Japanese persimmons, Diospyros kaki, often simply called kaki. It is a small tree that bears orange, fleshy fruit, delicious when eaten fresh or used for jams, breads and puddings.

Though kaki is the most frequently cultivated persimmon species, I don’t think it is as much a delicacy as our native persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, a much taller tree, common in yards and along streets in our local neighborhoods.

The female, fruit-producing trees are easy to find right now by looking for the soft, ripe, quarter-size (sometimes larger), darkened, plum-like fruit on the ground beneath the tree. I began collecting fallen ripe persimmons beneath my favorite tree a month ago, before the recent frosts. Old-timers say it takes several frosts to ripen persimmons. But not any more. Perhaps shorter day light is the trigger. There are lots more on the tree. They’ll be dropping for several weeks more.

The Japanese persimmon in the garden of the nature sanctuary where I sometimes serve as a guide for school groups also has already produced soft ripe fruit.

Note well that you don’t want to taste the fruit of either of these two persimmons if they are hard to the touch. Just accept the “It’ll turn your mouth inside out!†description of anyone who has tasted an unripe one.

Last week, a group of third-graders helped me compare these two persimmons. We tasted a ripe Japanese persimmon growing in the garden and then walked over to a native persimmon growing along the wood’s edge. As tasty as that bigger Japanese variety is, those youngsters, without any prompting from me, showed a preference for the flavor of the native.

Our native has an almost cult-like following. As described in the Nov. 1, 2007 Flora (“Persimmon seasonâ€), folks who treasure persimmons will stake out their favorite tree(s) wherever they are and visit frequently to harvest, hoping other folks don’t know about their secret.

European settlers learned early from Native Americans that this little fruit, sometimes called possum fruit, was good raw or cooked and could be dried for storage. A Native-American word, “pasiminan,†means dried fruit. This fall I’m going to dry a batch to try as dried delicacies.

Medicinally, the persimmon was used extensively. I am particularly intrigued by the description of chewing the bark for heartburn.

Persimmon'07 Though smaller than Japanese persimmon, the flavor of native persimmon has created a cult-like following of admirers. Photo by Ken Moore.

Being a close kin to the tropical ebony tree, the heavy, dark-brown wood of native persimmon has been used for golf clubs, weaver’s shuttles and other items requiring hard, smooth-wearing wood.

Being mindful of how much we have learned from Native Americans, make note of the 14th annual American Indian Heritage Celebration taking place on Saturday, Nov, 21, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the N.C. Museum of History, across from the N.C. legislature on Jones Street in Raleigh. Dance, food, demonstrations, story-telling and crafts from North Carolina’s Native American tribes are well worth scheduling into your weekend.

By Ken Moore

Remember that large genus of wildflowers in the aster (composite) plant family with the scientific name referring to some ancient king who thought one of the species was a poison antidote? Back in August, I described the many merits of boneset, Eupatorium perfoliatum, and more recently, two more Eupatoriums, flat-topped, blue flowered ageratum and the towering, feathery dog-fennel.

Please have patience as I indulge in describing another Eupatorium. I begin noticing it in early August, when the characteristic flat-topped inflorescences, the term for a plant’s flowering branch structure, begin bud formation. Single multi-stemmed plants or whole populations of them begin calling attention to themselves along the roadsides, where not in the path of frequent mowing.

Standing one to two feet tall, they look like puffy little clouds hovering just above the ground. Well, that’s the image I pull up whenever seeing them, and I enjoy weeks of roadside viewing as they gradually turn from pale-green to pure-white when they reach full flowering in September-October. Now as we move into the early weeks of winter, those plants are still attractive as grayish dried arrangements that last into the dead of winter. All three developmental stages of this plant are effective as a base or filler for flower arrangements.

This Eupatorium hyssopifolium, hyssopleaf Eupatorium, copies the leaf arrangement pattern of its namesake, the holy herb, hyssop. The short narrow leaves scattered up and down the stems usually have fascicles (tight clusters) of smaller leaves emerging from the leaf axils. I recall my delight decades ago when I learned to observe that “fascicled-leaves-along-the-stem†characteristic of this Eupatorium; until then they looked to me like any other roadside plant.

I remain in awe that plants like the whole group of Eupatoriums crowd so many tiny flowers into those variously structured inflorescences. It’s remarkable how many different insect pollinators are attracted to those flower heads. Our admiration should not stop with the flowers.

A closer look at the seed heads of those various Eupatoriums reveals, crowded together, thousands of single little seeds, little nutlets, called achenes by botanists. An even closer look with your hand lens, which I hope you always carry with you, will further reveal that each of those seeds are crowned with a ring of filament-like hairs.

These are the “parachutes†that carry those seeds aloft for wind dispersal. Now think about nature’s efficiency with this strategy. First of all, those seed plumes, so interlocked as they are, prevent all those seeds from being dispersed at once. You will notice that some of those seeds will hang on for weeks. That’s a plus for birds foraging during late fall and winter, and don’t be concerned for the plants; there are so many seeds produced that enough of them will gradually take flight on the winds to establish new plants near and far.

There are other Eupatoriums out there that we may not have noticed, but they are all being noticed by pollinators and seed-eating critters. And don’t fear, I won’t describe any more. I believe during the past few weeks, we’ve taken a closer look at the most engaging and useful of them.

By Ken Moore

One of my favorite drives is west out of Carrboro on N.C. 54. Along the way are forest edges, fields and vistas across hilly terrain, beautiful miniatures of the grand mountain views that are four or more hours drive away.

With each drive, I usually discover something of interest not observed before. I’ve been waiting since about this time last year to share my discovery of an impressive sumac tree I noticed exactly 3.5 miles from the edge of town.

I glimpsed on a fence line on the left-hand roadside the brilliant fall color of what I thought was a sassafras tree. On my return drive, I remained alert to take a closer look and was surprised to realize that my sassafras was really a winged sumac.

Now, winged sumac, Rhus copallina, is by nature a medium-height, rhizomatous shrub. A single seedling plant can produce a vigorous clump simply by extending its shallow horizontal roots (rhizomes) in all directions. When you see an extensive display of it, you may be looking at a single plant. I very seldom see it above five or six feet in height, a condition certainly maintained by roadside mowing schedules that are a constant threat to nature’s efforts at self expression.

The specimen along that farmyard fence is the only winged sumac I’ve ever seen that could be described as a tree. Since the length of that fence is always neatly trimmed of vegetation, I have a hunch that the property owners are largely responsible for helping this particular sumac attain its tree stature. I have a thicket of winged sumac, and I’m inclined to see whether I can encourage a tree from it – that is, if I don’t have to spend much time pruning the rest of the thicket.

This time of year, I find myself appreciating the shining brilliant-red of winged sumac as unsurpassed of all the fall colors, and then I spy the brilliant reds of its cousin, the smooth sumac, Rhus glabra (see Flora, Aug. 30, 2007), a larger similar rhizomatous roadside shrub. I guess my favorite fall color is whatever I’m viewing at any given moment.

Smooth sumac is easily distinguished from winged sumac by its vertical, conical seed heads that are displayed well into the winter. Winged sumac seed clusters are curled, round shapes that tend to present a messy effect. Looking closely at the center line (the rachis) of the compound leaves of winged sumac reveals a narrow flattened leafy surface along the edges, hence the description, winged sumac. Staghorn sumac, Rhus typhina, seen only in our mountain regions, is a similar but even taller species. There are great photos and descriptions of all the sumacs in Fall Color and Woodland Harvests, described in last week’s Flora.

We learned long ago from Native Americans that a refreshing drink, not unlike lemonade, can be made from the fresh berries of all three of these native sumacs; medicinal teas and other decoctions were made from the stem and root bark.

Winter leaf of crane-fly orchid emerges next to a coral fungus along the edge of Bolin Creek in the Adam’s tract nature preserve. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

It’s fall, and we have a winter’s worth of exploring along Bolin Creek ahead of us. I took my own solitary preview walk last Sunday.

My favorite access begins at the well-marked trailhead in Wilson Park that enters the Adams Tract nature preserve. An uphill walk through mature piney woods leads on over the oak-hickory forest and down through the beech-maple forest to the edge of the creek. All along the way, I could not help but pause frequently to admire mighty specimens of pine, oak, tulip poplar, beech and maple, each with an interesting story to relate, if only we knew how to talk to trees.

Well-worn trails lead in all directions along the creek’s corridors and on up into the Carolina North trails. It’s a close-to-home adventure to see if you can get yourself lost in these hundreds of acres of connected forests. If you succeed, you are never far from a trail that leads to a road or adjacent residential community.

It was a difficult choice Sunday for me to abandon enjoying the colorful wildflowers and grasses of fields and roadsides to enter the darker world of the forest. I was rewarded in rediscovering the beauty of fall’s lively awakening in so many ways.

The presence of so many different types of fungi (mushrooms) hugging the forest floor and clinging to fallen and standing trees reminded me that my mushroom guide was of little help left unattended on an indoor bookshelf. I took extra time out to appreciate a clump of coral fungus, so appropriately named for its underwater look-alike. This particular one seemed affectionately accompanied by the leaf of a crane-fly orchid, newly emerged for its seasonal growth to take advantage of the winter sun soon to be streaming through the leafless forest canopy. Numerous coral fungi are scattered about the forest floor. Some are edible and some are poisonous, so, unless you are an expert, enjoy with your eyes, but don’t touch.

I was surprised to see a few flowers of the witch hazel already open. They usually wait until closer to December. The leaves are just beginning to take on their beautiful golden-yellow tints, and a lot of them sported those characteristic little witch’s hat-shaped insect galls perched on the leaf’s upper surface. You can always identify a witch hazel if you find those little witch’s hats, because that particular insect lays its eggs only on the leaves of witch hazel.

We are fortunate here in our Piedmont that fall’s awakening goes on and on for weeks. It’s as exciting as springtime, with something new to discover with each trek outdoors. A great companion to help you appreciate the diversity and brilliance of our local fields and forests is Fall Color and Woodland Harvests, an easy-to-use visual guide to tree colors and nuts and berries by C. Ritchie Bell and Anne Lindsey.

Don’t miss the year’s annual Bolin Creek Festival from 1 to 5 p.m. this Saturday at Umstead Park in Chapel Hill. In addition to lots of activities for children, “Kid Fun,†you’ll meet a lot of the local folks who help care for the Bolin Creek corridor and get to help paint the Bolin Creek Community Mural.

See bolincreek.org for more details.

crane-fly-orchid-leaf-with- Winter leaf of crane-fly orchid emerges next to a coral fungus along the edge of Bolin Creek in the Adam’s tract nature preserve. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

It’s fall, and we have a winter’s worth of exploring along Bolin Creek ahead of us. I took my own solitary preview walk last Sunday.

My favorite access begins at the well-marked trailhead in Wilson Park that enters the Adams Tract nature preserve. An uphill walk through mature piney woods leads on over the oak-hickory forest and down through the beech-maple forest to the edge of the creek. All along the way, I could not help but pause frequently to admire mighty specimens of pine, oak, tulip poplar, beech and maple, each with an interesting story to relate, if only we knew how to talk to trees.

Well-worn trails lead in all directions along the creek’s corridors and on up into the Carolina North trails. It’s a close-to-home adventure to see if you can get yourself lost in these hundreds of acres of connected forests. If you succeed, you are never far from a trail that leads to a road or adjacent residential community.

It was a difficult choice Sunday for me to abandon enjoying the colorful wildflowers and grasses of fields and roadsides to enter the darker world of the forest. I was rewarded in rediscovering the beauty of fall’s lively awakening in so many ways.

The presence of so many different types of fungi (mushrooms) hugging the forest floor and clinging to fallen and standing trees reminded me that my mushroom guide was of little help left unattended on an indoor bookshelf. I took extra time out to appreciate a clump of coral fungus, so appropriately named for its underwater look-alike. This particular one seemed affectionately accompanied by the leaf of a crane-fly orchid, newly emerged for its seasonal growth to take advantage of the winter sun soon to be streaming through the leafless forest canopy. Numerous coral fungi are scattered about the forest floor. Some are edible and some are poisonous, so, unless you are an expert, enjoy with your eyes, but don’t touch.

witch-hazel-leaf-and-buds The little witch’s hat insect gall is a tell-tale mark of a witch hazel leaf. Photo by Ken Moore.

I was surprised to see a few flowers of the witch hazel already open. They usually wait until closer to December. The leaves are just beginning to take on their beautiful golden-yellow tints, and a lot of them sported those characteristic little witch’s hat-shaped insect galls perched on the leaf’s upper surface. You can always identify a witch hazel if you find those little witch’s hats, because that particular insect lays its eggs only on the leaves of witch hazel.

We are fortunate here in our Piedmont that fall’s awakening goes on and on for weeks. It’s as exciting as springtime, with something new to discover with each trek outdoors. A great companion to help you appreciate the diversity and brilliance of our local fields and forests is Fall Color and Woodland Harvests, an easy-to-use visual guide to tree colors and nuts and berries by C. Ritchie Bell and Anne Lindsey.

Eupatorium’s many shades and shapes

By Ken Moore

Eupatoriums have been featured in past Flora columns. Joe-Pye weed, Eupatorium fistulosum, that tall mid-summer, dome-shaped, butterfly-covered, pale-purple-flower-headed roadside one comes immediately to mind. Then there is the recently described flat-topped, white-flowered, boneset of medicinal fame; remember, the “perfoliate†leaf one, E. perfoliatum?

Well now, I’m not going to try to describe the two dozen or more different species of Eupatoriums growing throughout our state, but there are two that can easily catch your attention now along our roadsides.

First, let me comment a bit on the official name, Eupatorium (yew-pat-OR-ium). It’s from the Greek and commemorates Mithridates Eupator, King of Pontus, who is credited with the discovery that one species was an antidote against poison.

Perhaps it was one similar to our own boneset. So there you have a tidbit about the genus name for this group of wildflowers (call them weeds if you dare) that are a part of the large aster or composite family of plants.

Challenging you regular Flora readers, remember the flower characteristics of the aster family? The flowers are really tight clusters, heads, of tiny flowers in configurations of disc (tube) flowers in the center surrounded by a circle of ray flowers, like Black-eyed Susans, or heads of all ray flowers, like dandelions, or heads of disc flowers, like Joe-Pye weeds.

Eupatoriums are characterized by flat-toped, dome-shaped or other various-shaped clusters of hundreds and hundreds of heads of tiny disc flowers. You will want to devote at least a few minutes, if not half an hour, for a Eupatorium conversation at your next dinner party.

For a couple of weeks now, I’ve been admiring a misty purple flowered clump of E. coelestinum (see-less-TY-num) protected from mowers by the guardrail along the bypass crossing Smith Level Road. The species name, appropriately, means heavenly or sky blue. The common names include mistflower, blue boneset and ageratum, the latter likely familiar to most of us. Perennial ageratum has been passed along from garden to garden for so long that it is generally considered an escape from cultivation rather than the native it is. It’s fun to see it occurring in moist fields and roadside ditches this time of year. Next time you see it, take a closer look and try to count the number of disc flowers in a single head.

Volunteer dog fennel is a show-off in front of swamp sunflower in Diana Steele’s wild curbside garden. Photo by Ken Moore.

The other Eupatorium of note is E. capillifolium, the weedy dog fennel of pastures. The species name refers to the capillary-thin, thread-like leaves that make the whole plant look like a kid in need of a barber. Head-high perennial stems, gracefully waving thousands of dusty white to pale-burgundy disc flowers, may go unnoticed when growing so plentifully in fields, but a single plant in a garden border can be a real knockout. The volunteer specimen dog fennel in Diana Steele’s wild curbside garden on Mason Farm Road is worth a drive by.

While the merits of ageratum are mainly aesthetic, the merits of dog fennel are enhanced by a heritage of Native-American medicinal use. I’ll leave it to you to seek out some details from the Herbal Remedies of the Lumbee Indians or James Dukes’ Handbook of Northeastern Indian Medicinal Plants. I’m not certain I would use the new information for dinner table conversation, but I’ll forever admire dog fennel with greater appreciation.

Putting the garden to bed with nature

goldenrod Goldenrod flower stems produce fluffy seed heads that provide food for birds and winter interest in gardens and fields. Photo by Ken Moore.

By Ken Moore

The “fall is for planting†counterpart to the spring gardening frenzy is in full swing. While I marvel at the energy of gardeners planting, pruning, cleaning and “putting gardens to bed for the winter,†I just can’t bring myself to direct energy on any of these activities. I’m way too absorbed trying to keep pace with nature’s gardens peaking everywhere just now.

For me, the notion of “putting the garden to bed for the winter†has a sinister tone of finality about it. Though many plants take a so-called rest, the garden doesn’t stop in the winter.

Observing nature, you’ll note that some plants send up their leaves in the fall to take advantage of the winter sunlight. For many plants, the winter months are the true growing season.

Take special care of perennials with evergreen foliage or newly emerging green basal rosettes, like the hummingbird’s favorite cardinal flower. If you put those plants to bed with a blanket of mulch, you’ll lose them.

If you plan to cut down all those dried stems and fluffy seed heads, take another hint from nature’s wild gardens: tall branching stems and variously shaped capsules and fluffy seed heads remain standing to provide food and shelter for birds and other critters. In addition, the standing stems provide winter beauty with the play of sunlight and the capturing of dew and raindrops and, on rare occasions, snow and ice. Consider leaving a few of those seed heads and stems for the birds and added points of interest in your own garden.

Over the years, I’ve discovered nature to be a helpful gardening partner. Many of my original plants just couldn’t make it without excessive watering and other care. I simply could not water enough my favorite clump of Joe-Pye weed.

Fortunately, nature moved it by seed to other locations where they thrive without any help from me.

Nature also took charge of the design around my hot west-facing deck. The colorful perennial border along the edge slowly succumbed to the root and shade competition of a southern sugar maple that volunteered there. The shade of that tree now makes the deck habitable in the summer. I love that tree more than the original flower border.

As in nature’s gardens, each year I look forward to a different garden design around my house. I never know where the passion flower will emerge. I have to be vigilant to spot where the annual wild jimson weed will occur. Perennial poke, another favorite, is more predictable, but there are always new ones I select to leave here and there to replace old ones.

I’m always on the lookout for volunteer redbuds, dogwoods, black haws, sumacs and deciduous hollies. Selecting a few to leave in place ensures me truly maintenance-free specimen plants.

Swamp sunflower, coreopsis and boneset dominate the current spectacular fall wildflower display in the coastal plain habitat of the N.C. Botanical Garden. Photo by Ken Moore.

Letting nature become an active partner in planting and thereby influence the design of the ornamental garden has reduced my responsibilities to occasional pruning and weeding, leaving more time for the vegetable garden.

Whether or not you choose to partner with nature as you garden, take time out to enjoy nature’s gardens all along our country roadsides. A must-see natural garden is the coastal plain habitat at the N.C. Botanical Garden. It is unbelievable. At an all-time peak right now, the sculptural and color effects of the wildflowers rival the annual sculpture show outside and the paintings of Robert Johnson and botanical illustrators inside.

By Ken Moore

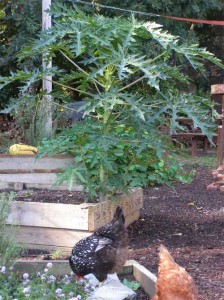

Though it’s sometimes called pawpaw, it can’t be confused with our native pawpaw, Asimina triloba, so frequently encountered along our stream corridors. The leaf of the tropical pawpaw, more commonly called papaya, Carica papaya, is deeply palmately lobed and dissected, looking more like a buckeye tree leaf having a bad hair day.

Papaya is a delicious tropical fruit-bearing plant that I haven’t seen since a visit to frost-free areas of southern Florida years ago.

So what’s it doing outdoors here in Carrboro? Some of the local folks visit the plant in wonderment on a daily basis.

So where can you see it? Go to Johnny’s on Main Street in Carrboro, halfway between the fire station and the post office. One of Brian Plaster’s staff at Johnny’s, Genero Rodriquez, buried a whole overripe papaya in a corner of one of the raised garden beds out back late last fall.

A few months ago, it started to emerge from beneath the tomato and pepper plants and is now showing off with cream-colored flowers and green baby papayas that sadly fall off before ripening.

Papayas, by nature, come in separate male and female plants, and, like our native persimmon and holly trees, you have to have both sexes around. Otherwise, we can’t look forward to persimmon pudding in the fall or red holly berries for holiday decoration.

Though there are some papaya cultivars that have perfect flowers, bearing both male and female parts, Johnny’s single plant is not one of them.

That papaya is not going to produce ripe fruit, and it is not going to survive the frost that will eventually arrive. Even though it’s the beginning of October, you most likely will have several more weeks to be one of the many visitors to view Genero’s papaya at Johnny’s.

Take the kids by for a visit. I would love to have just a hint of the thoughts in the heads of some of the youngsters I’ve seen gazing up from beneath the giant leaves of that papaya plant during the past couple of weeks.

Of South American origin, domestication of papaya most likely began in the Amazonian basin. It is a common breakfast fruit in much of the tropics. In addition to the fruit, the seeds are edible, credited with having a flavor a bit like watercress, and the tender leaves are prepared like spinach.

Without a male plant close by, these female papaya flowers will never produce a mature fruit; the young fruit shown at lower right will soon drop. Photo by Ken Moore.

Unripe fruit and the leaves are credited with producing an enzyme that is used as a dietary supplement to aid digestion. It is also used as a component in meat tenderizers and, perhaps of interest to some Carrborites, used to prevent cloudiness in bottled beers.

In future years, as our growing season becomes longer, Johnny’s may have more than one papaya plant growing, with a better chance of both sexes being present, and a greater opportunity for ripe fruit here above the tropics.