By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

This is the time of year to observe the open flower heads of sumac slowly close in as the maturing berries come together to form the dark red seed cones that are so striking along roadsides during the fall.

Four years ago, Kathy and I left the heat of North Carolina August to visit cousins on an island off the coast of Maine. I was not looking forward to the long drive and hazards of highway travels, but as always, I calmed myself by studying the roadside vegetation along the way. Like any wild botanist, I’m happily challenged when identifying plants at 60-plus miles-per-hour. That’s why my wife prefers to drive, which is fine with me and she remains much calmer.

All the way to Maine we enjoyed patches of sumac along the roadsides. In some states, mowing crews had deliberately left the patches; sadly, in others, similar patches had been mowed or killed by herbicide application.

Our local smooth sumac, Rhus glabra, grows throughout the eastern states and overlaps with its hairy-stemmed, bigger cousin, staghorn sumac, Rhus typhina, in the Carolina mountains and northern states.

Sumac patches add dramatic landscape effect along roadsides through all the seasons: vigorous green foliage during spring and summer, red seed cone accents in late summer, brilliant orange-red foliage in the fall and red seed cone-topped bare stems during the winter months. Truly a plant for all seasons!

I am thankful for the sumac that volunteered along our Carrboro roadside. It’s now well established and I look forward every year to finding where new stems emerge. It’s easy to extract it from spots I want to keep open for other plants, but more controlling gardeners will have less patience with the exuberance of sumac.

Occasionally a sumac may produce only staminate (male) flower clusters and thus will not produce those red seed cones, but the leaves will still have the spectacular fall color.

Sumacs are a popular plant for fall color in English gardens and there are several notable cut-leaf cultivars, such as R. glabra ‘Laciniata’ and R. typhina ‘Laciniata’ for fashion-conscious gardeners. For me, the wild form is just fine!

Sumacs are valued for more than their beauty. Daniel Moerman’s Native American Ethnobotany devotes several pages to sumac’s rich medicinal heritage. A refreshing tea concocted from the crushed berries is enjoyed by many. Culinary uses are engagingly described in Euell Gibbons’ Stalking the Wild Asparagus, Tom Brown’s Field Guide: Wild Edible and Medicinal Plants and James Duke’s Handbook of Edible Weeds.

Sumacs are members of the cashew plant family, Anacardiaceae, which provides us with the popular cashews, pistachios and mangos. It’s interesting that plants in this economically important family contain poisonous components. Fortunately, most of us are not allergic to the mango and nut sumac relatives, but we have learned to keep our distance from its less appealing close kin, poison ivy, Rhus radicans, and poison oak, Rhus toxicodendron.

I was amused years ago by my cousin’s determination to eradicate the beautiful nonpoisonous sumac around his island cottage. Now, years later, I’m happy to find that, like me, he allows it freedom to roam.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Jimsonweeds will volunteer wherever there is open ground. They generally don’t show up until early in the summer, and this year, in spite of the heat and the drought, I’m observing seedlings emerging late in the season. I’ve learned to recognize baby jimsonweeds because I want to have at least a few scattered about the garden. Nothing else looks quite like juvenile jimsonweed’s distinctive narrow triangular leaves with scalloped margins.

Poisonous, night-flowering jimsonweed, Datura stramonium, is a native annual, never seen in cultivated gardens. Close-relative garden varieties of Datura, also called thorn apple, and Brugmansia, angel trumpets, are frequently seen in gardens these days. They are all beautiful, and we need to be aware they are all poisonous. Flowers of cultivated thorn apple are upright trumpet-shaped flowers 6 or more inches long. The even larger cream and peach-colored flowers of angel trumpets hang down beneath the leaves.

The native jimsonweed has a smaller flower, only 3 to 4 inches long, angled upward in the axils of sturdy branches on a 3- to 6-foot-tall plant. It seems more a small shrub than a tall annual. Each ghostly white, trumpet-shaped flower bears an intriguing purple center. It opens in the early evening to be pollinated by night-flying insects searching for pale-colored glow-in-the-dark, heavily scented flowers. The flower’s mysterious musty scent is alluring, and viewing them during evening explorations is a special experience.

Though poisonous, the plant has a rich medicinal heritage. Quoting Jim Duke (Handbook of Northeastern Indian Medicinal Plants): “In Virginia, Algonquin fed male pubic initiates tea made from Datura, enough to keep them drugged for two to three weeks. Such initiates were supposed to forget everything and learn again, as men, not boys.†Apparently Capt. John Smith’s followers at Jamestown tried this native custom, resulting in lengthy nonproductive stupors. It became known as loco weed and Jamestown weed. As often happens, names change as they are handed down through the years. “Jamestown weed†became “jimsonweed.â€

I am amused with Paul Green’s recollection (Paul Green’s Plant Book): “We children used to have great fun in the dusk of warm summer evenings chasing after great tobacco moths that haunted the strong scented blooms of the jimson weed. I read in an old book once where it said that harem wives in Turkey were wont to chew this weed and swallow the juice to strengthen their powers of love. I wonder what the head of the harem, the old Turk himself, chewed.â€

Though it is a common plant throughout the state, most people miss the evening flowering and are intrigued when discovering it during winter walks when it is a curious-looking stem of bare branches with spiny egg-shaped pods. You may want to collect a few seeds and scatter them in a corner of your garden for some night flowers of your own.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Here’s a flower you won’t pick!

PHOTO BY PARKER CHESSON. Swallowtails are one of many insects attracted to bull thistle flower heads.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Durham resident Parker Chesson recently captured the above image of a swallowtail on a bull thistle flower head. Parker continued his “closer look†and then captured (see back-page photo) the pre-expulsion stage of a mature seed head, which is every bit as beautiful as the flower itself. I’ve observed bull thistle seed heads countless times without ever catching this particular moment in time.

Bull thistle, Cirsium vulgare, more commonly called spear thistle in Great Britain, is an alien plant on our turf. Needle-sharp spines cover the entire plant; farmers and horse owners curse it in their fields. It’s listed as a “plant to avoid†on the N.C. Botanical Garden’s website, and the N.C. Native Plant Society (ncwildflower.org) includes it on their Rank 3 list of unwanted invasives.

It can be easily spotted in small populations on disturbed ground and along roadsides. The peak of thistle flowering has passed, though you will likely spot a few still flowering here and there. Most notable just now are the silky plumed seeds soaring aloft on summer breezes. It may be a surprise that those bits of flying silk come from that brilliant-purple thistle head. Thistle flower heads are visited by several butterfly species and other colorful winged pollinators partaking in what must be a nectar feast. I was fortunate to have a seldom-seen zebra swallowtail visit one of the volunteer plants in my yard last week.

The purple flower head, another example of the aster (composite) family’s compact head of disc or tube flowers, is mature for only a single day. Almost overnight, that needle-barbed flower head changes to a ball of silky fluff ready to take flight. It’s fun to watch goldfinches brave the spiny heads to eat the ripe seeds. I believe those goldfinches are pretty efficient in harvesting the ripe seed – because every time I pluck one of those flying seed plumes from the air, I find the seed missing. So perhaps the birds are helping keep this exotic in check.

For several years, armed with sturdy gloves, I enjoyed taking a stem or two of the thistle flowers to an old friend of Scottish heritage. Even with gloves, I found the experience painfully prickly.

It’s easy to accept the stories that the early Scots adopted the spear thistle as their national emblem because of the numerous tales of invaders running into fields of thistles and crying out in pain, thus alerting the defending Scots. Though historians still debate which particular thistle is the official Scottish Thistle, most have settled on this one.

Rather hard to believe are the various accounts of the edible and medicinal qualities of this otherwise untouchable weed. Space doesn’t allow for them here, but for those of you interested, go to Jim Duke’s Handbook of Edible Weeds and Tom Brown Jr.’s Tom Brown’s Field Guide: Wild Edible and Medicinal Plants for downright mouthwatering descriptions of harvesting and preparing spear thistle roots, stems, leaves and flower heads.

So next time you’re out and about, tread softly among the Cirsium vulgare as you share what you know with your walking companion!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Another spectacular Piedmont wildflower display

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

I jump for joy when I view a field of wildflowers, especially here in our Piedmont region.

Such was the case last Friday at Penny’s Bend Nature Preserve, just north of Durham, near where Old Oxford Road crosses the Eno River. The N.C. Botanical Garden has managed this 84-acre remnant Piedmont savanna ecosystem for several decades. Garden staff and volunteers plan and execute seasonal prescribed fires as a biological management tool in pursuit of returning the area to its former historical savanna status.

Seasonal savanna wildflower displays are returning to the site. Some of you may have enjoyed one of the Botanical Garden’s interpretive walks offered earlier in the year to view blue wild indigo, wild quinine and smooth coneflower. Just now, the forest edges and open areas are filled with rosinweed, Silphium astericus, in full flower. Though small populations of rosinweed occur here and there along our rural roadsides, the current display at Penny’s Bend is no less than spectacular.

In spite of 100-plus-degree heat and drought, the field was alive with butterflies and other winged pollinators. Coming into peak flower on the heels of the Silphium are three species of goldenrod, and numerous marsh mallows and buttonbushes continue to flower along the pond edges. The display of wildflowers and grasses will continue through the fall.

From the parking area near the Eno River bridge, a walking path provides access to the preserve’s trails, which are maintained for self-guided walks. If you plan now, you can register for a Botanical Garden (ncbg.unc.edu) fall excursion to Penny’s Bend. Ed Harrison, preserve-management committee member, will be leading two walks in October to catch later spectacular wildflower and native grasses displays.

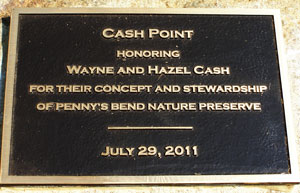

Last Friday was a special occasion at the preserve. The Botanical Garden unveiled a bronze plaque on a boulder at the site’s highest point, designating it “Cash Point,†recognizing Wayne and Hazel Cash for their years of stewardship on the land. Hazel and Wayne were residents of the site when Falls Lake became a reality. The Army Corps of Engineers, N.C. Division of Water Resources and the Botanical Garden Foundation joined hands to designate the site a preserve of biological significance, and Wayne and Hazel remained in their home on the land for many years as site managers and preserve curators for the Botanical Garden.

A plaque honoring Wayne and Hazel Cash for their many years of stewardship at Penny’s Bend Photo by Ken Moore

The hot July day selected for the recognition was determined by Wayne’s annual summer visit to his old stomping grounds. The extreme heat prevented Hazel from attending; however, she was present in the many comments of appreciation and happy stories that attendees told about the Wayne and Hazel Cash days at Penny’s Bend.

Whenever and wherever we make time to step out on nature’s pathways, how wise of us to pause and reflect and be appreciative of folks, like Wayne and Hazel, who have walked the land before us.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

“Mother Nature’s daily specialâ€

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Monterey Valley kisses the southern end of University Lake

And holds a fascinating primordial stirring of upthrusting rock

And most fecund ferned and fungied transitional forest.

First thing in the morning and last in the day

I walk with my camera into some astonishing display

Mother Nature’s daily special.

Violet, yellow, white

And no matter how tiny it lays down there

On the bosom of Earth

It has my eye and my Heart.

That’s how I fall in love with wildflowers

Again and again and again.

They cast such a spell that simply gazing

In wonder brings purest tonic of Joy.

It takes no learning for the pleasure itself is a teacher

And then you simply begin to get acquainted.

Thanks to Brian Stokes for the above description of his daily walks in nearby woods. Brian is fortunate to be situated near the forest bordering Price Creek on both sides of Damascus Church Road at the southern end of University Lake.

Brian’s daily “closer looks†at the local flora called to my attention several common but seldom-noticed wildflowers of particular beauty.

The little white-flowered buttonweed, Diodia virginica, is common throughout the state in roadside ditches and even possibly scattered among the violets and dandelions, if you allow them, in your lawn. Diodia teres is very similar and also common, but you need not worry about the distinctions. Just enjoy that the distinctive four-petaled flowers may remind you of bluets or Quaker ladies you saw back in the cool spring, as well as the woodland evergreen groundcover, partridge berry. They all occupy places in the madder family, Rubiaceae, and you can share that with your friends! The common name, buttonweed, most likely refers to the little seedpods that resemble old-timey little round buttons.

Brian’s other special of the day is butterfly pea, Clitoria mariana, which while very common seems to bashfully keep its ternately (in threes) compound leafy vines hidden among woodland edges. It may attract your attention only when one of those vivid lavender-blue pea flowers greets the day. It is so beautiful that it simply needs no other description. In Brian’s words: “… simply gazing in wonder brings purest tonic of Joy.â€

I mentioned the area along Price Creek many months ago (“Take an Avatar walk,†2/4/10) after local musician Tim Stambaugh described it as one of his favorite nature haunts. This past winter, I joined a Heritage Hills resident in walking the path behind the community’s tennis court. The low flat terrain includes a cypress swamp, which is a magical-in-all-seasons place, but, for most folks, probably best explored in the winter season, when poison ivy is dormant. In dramatic contrast are the paths bordering Brian’s Monterey Valley area of giant boulders and undulating steeper terrain.

As I described in that earlier story about viewing our local forests as Avatar-like landscapes, both Brian and Tim appreciate their “closer look†walks that reward them with the naked, heart-stopping wonder of really seeing the living world. As Brian so beautifully expressed it: “Mother Nature’s daily special.â€

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

by Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

I am amused by humorist Andy Borowitz’s annual description of “pointless filler columns,†submitted by columnists when they take out-of-town breaks. He describes the characteristics of such pieces as rehashing older columns, using lengthy quotes and repetition throughout the column.

As described in Paul Green’s Plant Book, “Pokeweed, pokeberry, poke, is found almost everywhere from Canada and the Dakotas down to Florida. The young shoots are often used for salad or a substitute for asparagus. One of the best folk remedy plants in the Cape Fear River Valley. … An ointment made from the root was good for all kinds of skin diseases. … Indian runners on long journeys used to chew the leaves to quench the thirst, so it was said. Pokeroot tea was especially good for hog cholera. The leaves and the berries (sometimes called pigeon berries) and the roots are purgative and narcotic. A tincture of the ripe berries has been used as a popular remedy for chronic rheumatism.â€

Poke stories abound. Green includes a wild story about poke used as a poison ivy cure. I suspect you won’t try the cure, but you will never forget the tale.

While most folks frown on common pokeweed or poke salad, Phytolacca americana, sophisticated gardeners like my friend Sally Heiney admire and grow this giant native perennial.

Every year, Sally and I engage in “my-poke’s-bigger-than-your-poke†discussions that require regular garden visitations to determine who gets the annual bragging rights.

Poke is my favorite plant, striking in all seasons. My favorite aspect is probably the stem. Poke’s brilliant red stems in late summer and early fall literally stop me in my tracks. There is no more spectacular effect in either the wild or a managed landscape.

I love everything about poke. Tiny pendulous flowers bloom throughout the growing season. A closer look reveals white petals surrounding emerald-green centers, contrasting with pink- to burgundy-colored stems. What color combos!

Even in the dormant months, the tan-colored stems of poke remain an interesting architectural feature. I never cut stems down until the emergence of the lush green leaves at the base of the plant in the early spring. Then we refer to it as poke salad. Visit the farmers’ market in early spring to get cooking strategies from some of the old-timers. Make certain you note the details, because poke is also poisonous, so you have to know what you are doing to safely enjoy this culinary treat.

Poke is also medicinal. Wish I had the space to relate my annual conversation with a friend who collects pint jars of dried berries for her 90-year-old aunt, who concocts a special tea to relieve pain from arthritis and rheumatism. But don’t you try it until you know what you’re doing!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

You know, folks, I generally have two or more stories and photos queued up for Flora ahead of submission deadlines. Once in a while, I unexpectedly happen upon something that engages me enough to write on a topic at the last minute to slip in ahead of the stories already in the queue.

In the last several months, I have been responding more and more to comments and inquiries from Citizen readers. These folks, in sharing their own “closer look†observations, often steer me into an unintended next story. Flora is gradually evolving into a series of reader-inspired columns, for which I am appreciative.

This happened just this past week. In response to my description of plantain, Citizen reader Allies Scales shared that plantain leaves reminded her of the dock leaves she remembered finding in England, invariably in close proximity to nettle patches, since, as children, she and her friends learned that crushing dock leaves and rubbing them on the skin took the hurt out of close encounters with stinging nettles. Her curiosity led her to wonder if perhaps plantain and dock, both useful medicinal weeds, may be in the same plant family. She was also curious about other complimentary plant pairs that may grow close to one another.

So, thank you, Allies, for focusing my attention on dock for this week’s Flora.

How convenient that my wild yard-garden is filled with dock, which I have considered featuring for years but has just never ended up in the queue.

Common dock, Rumex crispus, is frequently called curly dock, because its giant leaves are curly or wavy along the margins.

The greenish flowers of dock almost immediately develop into the characteristic winged seed of buckwheat. Dock is in the smartweed family, Polygonaceae, not the plantain family. The smartweed family contains the well-known buckwheat. The buckwheat-like winged seeds of curly dock are beautiful as they turn from pale green to crispy burnt-brown colors. To me, they appear as tiny jewels of form and color during the transition.

For years, I have been cutting the stems of dock’s clusters of greenish flowers and ripening seeds to enjoy singly or with other plants as indoor flower arrangements. Like so many weedy plants, when we step back and take a thoughtful look we can find amazing beauty.

I vividly remember an older friend visiting in the springtime, running around the yard like a madman, collecting fresh leaves of our dock plants, scolding us that we were letting all those fresh, healthy green leaves go to waste. Now, years later, I’m much more appreciative of his “wild weeds†wisdom.

Leaves in the early spring, fresh or cooked, are rich in protein and vitamin A. If leaves are tough, they need to be boiled a couple of times and the liquid tossed.

Dock also has numerous medicinal attributes – too many to describe in this limited space.

And yes, Allies, there are other companion plants growing nearby, like our native jewelweed, reverently held as a cure for poison ivy, but that’s a Flora story queued up for sometime in the future.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Trumpet creeper, one of our fine native vines

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Recently, I was queried by a Citizen reader about why I never write about vines. This reader had missed my Flora stories on coral honeysuckle and cross vine earlier in the year. During the same week, premier “gardener-in-a-small-space†Bill Bracey was wondering why folks did not make more use of vines in gardens. His small-space garden, Shelby’s Bottom, halfway down Hillsborough Street in Chapel Hill, has native vines galore.

So, I’m inclined to dedicate a good bit of the summer to a review of our native vines. If you recognize some of the features as ones you’ve seen before, it’s not because I’m out of town and submitting one of those “pointless filler columns†that humorist Andy Borowitz exposes so effectively in his annual Labor Day column – I’m merely following some suggestions from Citizen readers.

So now, I’m again celebrating trumpet creeper, Campsis radicans. Some folks call it trumpet vine or cow-itch vine. There are likely other names associated with this common native vine, the bright-orange, tubular flowers of which are guaranteed to attract hummingbirds. Keep an eye out to find occasional peach- and yellow-colored variations. Garden centers offer cultivars that have peach or red flowers, and you may find the larger, red-flowered Chinese trumpet creeper, Campsis grandiflora.

As far as I’m concerned, any naturally occurring form of this common vine is just fine, and the hummingbirds don’t distinguish one from another.

Don’t let its pinnately compound leaves make you think the vine is wisteria. The compound leaves of trumpet creepers are opposite one another on the stem, in contrast to the alternate leaf arrangement of the awful exotic invasive wisteria.

Wisteria vines coil around and kill trees; trumpet creepers simply clamber loosely up trees without harming them. Flowers hang in clusters at the tips of long stems reaching down from points of varying heights, like low fence posts or abandoned chimneys.

They are quite noticeable, once you learn to recognize them, overstretching the guardrails of our highways. Recently, I’ve been admiring some peachy-colored ones overhanging the guardrail along the eastbound lanes of I-40 just past The Streets at Southpoint intersection. Be warned, however, that this is not a good spot to slow down for a closer look. Just take pride in knowing what you’re seeing.

Closer to home is a mighty hardy trumpet creeper overhanging the retaining wall along the westbound N.C. 54 bypass exit onto Jones Ferry Road.

Don’t attempt a ‘closer look’ at trumpet creeper hanging over highway guardrails. Photo by Ken Moore

I’m fortunate to have a trumpet creeper that volunteered at the base of my bird-feeding posts just outside my kitchen window. For years now, that vine has been showing off with flowers, with their accompanying pollinating hummingbirds, from early to late summer. I discovered several winters ago that goldfinches love to cling to the dried bean pod-like seed capsules to tease out the winged seeds during the early-winter months.

So, for those of you who already know this common native vine and for those who are just becoming familiar with it, I hope you find some to enjoy.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

After recently seeing some handsome specimens of common plantain, Plantago major, up in the Carolina mountains, I was happy to arrive home to find my own wild population showing off impressively in spite of the harsh hot and dry conditions.

I usually review what others have had to say about my “plant of the week†before I add my observations. I’m happy that this week’s plant is included in my favorite reference, Tom Brown’s Guide to Wild Edible and Medicinal Plants by well-known wilderness survival teacher Tom Brown Jr.

In Tom’s words: “Plantain is a lover of lawns, gardens, roadsides and fields. Leaves of the common plantain are in basal rosettes, found low to the ground. The leaves are roundish, heavily ribbed and very broad with flattened stems. It flowers from summer to mid-fall. The greenish-white tiny flowers are found along leafless stems. One or more species of plantain is found throughout the United States.â€

Indeed, those flowers are tiny. Even with your trusty hand lens, a closer look will barely let you discern those minuscule tubular flowers from which extend the more visible white anthers.

While taking my closer look, I was joined by a beautiful green planthopper that also seemed to be having a closer look at the green flower spike. So often, visiting pollinators, or just curious insect visitors, are every bit as engaging to the observer as the plant or flower. The cool green beauty and casual attitude of the planthopper was a pleasant surprise.

Considered by most a ubiquitous weed, plantain is sometimes called whiteman’s-foot, thought to have arrived in America on the feet of European settlers. Some taxonomists, however, consider that it may be native to the northeastern U.S. Regardless, it is everywhere, and maligned throughout as a weed.

I return to Tom Brown. His mentor, Grandfather, was a wise Apache elder who absorbed the valued lessons of all cultures. Referring to a discussion he had with Grandfather as to why people refer to plants as weeds, Tom writes: “To me, it is an alien term, because every plant I knew had some use or another. Some of them were very critical to survival conditions and I could not have made it through many an outing without them. Grandfather said most people’s feet are removed from the soil and the wisdom of their ancient ancestors. Because of cultivated crops and other customs, many plants and animals have little or no use to modern man, which is why he is so apt to destroy them without a second thought.

“Plants are edible, medicinal or utilitarian in some way. Grandfather stated emphatically that even if we did not know the use of a plant, we should consider its importance to the overall plan of the natural world. Nothing has been put on this Earth without a very definite purpose.â€

Early on, Grandfather had learned to prize plantains for both food and medicine, and he taught young Tom many uses, from the nourishing values of leaves and seeds to the almost legendary medicinal properties of leaves, roots and seeds. To the Navajo, plantain was the “life medicine.†Wisdom helps us view a lawn of plantain as an asset.

I now have an additional enthusiasm for plantains. Several years ago, I noticed that some of my robustly growing plantains somewhat resembled the revered horticultural hostas. Knowing how gardeners are in constant battle with the hosta-loving deer, I decided that I would adopt these deer-proof hosta look-alikes as prized specimens. In the next day or two, I’m going to pot up a few to grow as foliage plants on the deck. I imagine that with extra water and compost, I’ll have specimen plants that will be the envy of west Carrboro.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

For years and years, I’ve been admiring bottlebrush grass, a wild grass of the open forests and woods’ edges, and now I enjoy it all around me day after day. It’s one of those plants that doesn’t shout out at you every time you look its way; rather, it can go almost unnoticed, and suddenly there

Several years ago, I had to rely on finding it only occasionally here and there along a woodland path. I once brought home a handful for a dried arrangement, and at the same time I casually scattered a few seed spikes around the edges of the yard wishing that nature would produce a few plants for me.

A couple of years later, I spied a few over in the edge of the woods next to the drive. Then, each year, a few more clumps appeared here and there, and now I have them in several places at far edges and up close near the steps and along the deck.

I first learned this grass as Hystrix patula. Hystrix is from the Greek Hustrix, which means porcupine, an obvious reference to the bristly appearance of the flower spikes. The current official name is Elymus hystrix, so if you learned the old name you at least have a jumpstart on learning half of the new name. Elymus is the genus name for native wild rye grasses, and the bottlebrush is distinctive because the flower spikes are much more open than those of the other species.

These native wild ryes occur throughout the nation and, where abundant, are important forage grasses forming part of the native hay. In contrast, our bottlebrush (it does resemble a bottlebrush scrubbing utensil) is not an important forage grass because it does not occur in great abundance. It is, however, an indicator of a natural forest of high quality.

Bottlebrush definitely has value as an ornamental, particularly in a natural garden where one does not need to be particular about watering and other worries of cultivated gardens. Unlike the aggressive river oats, another ornamental native grass, bottlebrush does not vigorously claim territory, denying other cherished plants their own plot of ground.

Last week when I visited my wild-gardening friend Pete Schubert in his Durham garden, I was blown away by the stand of bottlebrush grass on the edge of his woods. The flower spikes of his bottlebrush are almost snow white and seemed to glow against the shadows of his woods. My bottlebrush plants are not that showy. I’m encouraging Pete to multiply his plants and, who knows, in a few years we may have local nurseries offering Elymus hystrix, “Pete’s White.†Perhaps we’ll simply call it “Pete’s White Bottlebrush.â€

Another of life’s simple pleasures!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com.

Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.