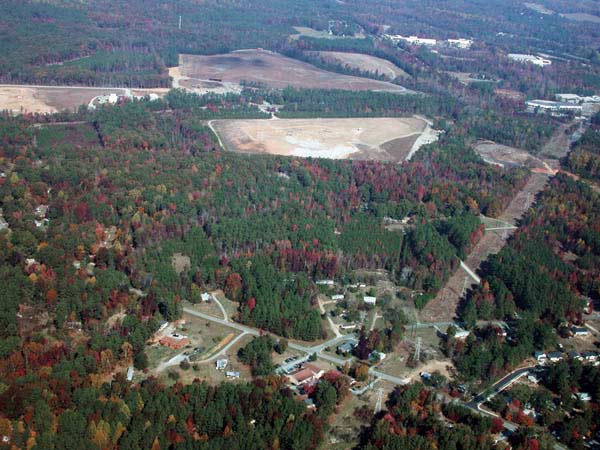

Photo by Robert Dickson

Aerial view of the Orange County Landfill and the Rogers-Eubanks Road community. Rogers Road runs diagonally in the foreground.Â

Editor’s note: This story is the third in a series that examines issues related to environmental justice and to the fight of the Rogers and Eubanks roads community to be relieved of what they allege to be an undue burden. To read the stories in this series and for other resources, go to www.carrborocitizen.com/main/rogers-road

By Taylor Sisk

Staff Writer

To a young Neloa Jones, it was simply “the homeplace.†Jones grew up mostly in Maryland, but would come down once or more a year, back in the late ’60s and early ’70s, to visit with family – the Rogers, the Barbees, the Wests and others – families with deep and rich heritages in this community to the north of Chapel Hill. It was from her grandmother, Velcie Rogers Barbee, that Jones first heard the community, once a township, referred to as the homeplace.

Today Jones is a resident of that neighborhood – most commonly referred to as the Rogers Road community – and a spokesperson for the Rogers-Eubanks Coalition to End Environmental Racism, an organization working to keep a solid-waste facility out of the community and to gain enhancements in return for having housed landfill facilities for the past 35 years.

“Every Sunday morning she would get up,†Jones says of her grandmother, “she would go to church; she would come back. And you always knew, her routine was always the same: She would say, ‘Well; I’m going out to the homeplace,’ because all her sisters lived out here.â€

This was before the neighborhood on and around Rogers Road, bordered by Eubanks Road to the north and Homestead Road to the south, came to sometimes be known as the “landfill-neighbor community†(“hardly a neighbor,†says Jones), back when neighbors were family. The little log cabin that sits just beyond Jones’ driveway belonged to her aunt Gracie Rogers. Her great-grandfather, Sam Rogers, lived in the two-story antebellum home on Purefoy that Jones’ kin called the “Plantation House,†also known as the Lloyd-Rogers house. Sam Rogers lost that home to the Depression, when all he owed on it was $600 in mortgage debt. He also lost all his land, which, Jones is told, began at the railroad tracks on Homestead Road and stretched along what is now Billabong Street up to Purefoy Drive, some 100 acres.

Jones says her elder relatives have always told her that everyone north of Edgar Street – a gravel road off Purefoy Drive, which is off Rogers Road, and where Jones and her husband, Stanley, came to build a home on a six-and-a-half-acre parcel of land – is related by blood or marriage.

Most everyone familiar with the particulars of the history of the Orange County Landfill will acknowledge that there were some very good reasons for that landfill being sited where it originally was, on the north side of Eubanks Road.

Gayle Wilson, solid-waste management director for the county, knows a great deal about what constitutes a favorable solid-waste site. And though the decision, in 1972, to place the landfill predates his service with the county, he says the Eubanks site is a good one, most particularly in that it has good hydrology characteristics – meaning, says Wilson, “We know exactly where the water flows, which is important.â€

Allegations have been made over the years of well water being contaminated by the landfill.

Wilson says that on two occasions – once in the ’80s and again in the ’90s – the state Division of Environmental Health conducted, in response to community concerns, a series of monitorings of various wells in the area.

Wilson says the tests determined that a number of wells in the community were in fact contaminated, but not by any of the trace chemicals typically associated with the landfill.

“And in fact,†he says, the division “came to the conclusion that the source of the problem, as far as they could tell, was that wells had either been poorly constructed or, if properly constructed, had deteriorated, and that in many cases they were being contaminated by things on or near their properties, such as failing septic systems.â€

“If there were to be a leak, it almost certainly would not flow toward Rogers Road,†Wilson says, “it would flow away from Rogers Road to the northeast.â€

Justice deferred

Where opinions begin to dramatically differ is in the decisions that have been made in the 35 years since the landfill opened. The landfill area on Eubanks was to have been sealed up in 10 years (and covered by a park), then 20, and so on.

Then, last March — just when it seemed the end was finally near, with the landfill due to reach capacity in 2011 — a decision was made by the Orange County Board of Commissioners to place a solid-waste transfer station on the same county-owned property.

“Enough is quite a bit more than enough†was essentially the message conveyed to the board by the Rogers Road community and its supporters. That Eubanks would even be considered as a location for the station was, said the community’s spokespersons – in a now strong, clear and unified voice — an outrage. Justice deferred is justice denied, they said, and this community had long felt denied.

On Nov. 5, the commissioners elected to reopen the transfer station search process, though they haven’t yet ruled Eubanks Road out as a potential site.

“If indeed you are representing the people,†says Commissioner Valerie Foushee, “and the people say — and the people say loudly, and the people say in large numbers — ‘I don’t think you got this one right,’ who are we to say, ‘Yeah, well, we’re the five that you elected, and whatever we say is right.’

“No; that’s not the case.â€

This “landfill-neighbor community,†bolstered by the leadership of the Rogers-Eubanks Coalition to End Environmental Racism, had spoken, and been heard.

A smell like ‘rotting animals’

Neloa Jones hadn’t given much thought to the family property up on Edgar Street, at the homeplace, until she and her husband decided to move back to the area from Wilson.

“We walked through the land — it was all wooded at the time — and we said, ‘It is absolutely beautiful.’ It was absolutely gorgeous to walk through. And I said, ‘Well, Stanley, we can try to figure out how to buy a $250,000 house where the houses are close together’ — but we were used to having a little bit of space.

“We decided this was the place for us to be. … And my father said, ‘You can have the land.’ So we decided to stay here. But we always thought that this would disappear,†she says, gesturing out the glass door that leads to her backyard, and, perhaps less than a 100 yards beyond, to the mounds of dirt that demarcate the landfill’s boundary.

(Gayle Wilson says this landfill couldn’t be built today in the same location because the current regulations for municipal solid-waste landfills require a 300-foot buffer from residences. When it was built, a 100-foot buffer was the law.)

“Everyone told us the landfill is closing in 2007, 2008, 2009,†Jones says. “The years kept going up.†And when the wind blows just so, the landfill asserts its authority.

Jones’ mother was recently paying a visit, and the two were relaxing on the front porch. “What is that smell?†asked her mother. “And I said,†Jones recalls, “‘oh, that’s just the garbage again.â€â€™

Foushee was aware of what the Rogers Road community had endured.

One recent night, at around 10:15, she received a call from Rev. Robert Campbell, a community leader.

“I had come from a meeting,†Foushee says. “He called and he said, ‘If you can, would you ride out here and smell what we smell?’

“It was really cold, and I didn’t feel like going out because I was preparing for bed. … But I decided to do it anyway. And it was awful.â€

At the commissioners’ meeting in which the decision was made to reopen the transfer station search, Foushee described the odor as “putrid.â€

“It smelled like rotting animals,†she now adds.

“It’s not as if I hadn’t believed what I had heard. There was no way that you could doubt the anecdotal information that we’ve heard to this point. So I think going out there was more about honoring a request of a citizen, and walking a mile in his or her shoes. Because [even though] I can take what I’m hearing to be true, if you haven’t lived it you can only imagine it. And that took me beyond imagination.â€

As progressive as we believe?

In the early 1980s, the environmental justice movement was gaining momentum across the country, triggered by events in a small rural county in eastern North Carolina. (See “The grassroots of environmental justiceâ€: www.carrborocitizen.com/main/rogers-road.)

The fundamental principals of environmental justice, as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, are for “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.â€

So how are we doing here in this community in keeping with the above-stated principles?

Not so good, says Carrboro Alderman Joal Hall Broun.

“This community is always patting itself on the back for being progressive,†says Broun. But “maybe we’re not as progressive as we really think we are. Does what we say really comport with what we do.â€

“When you’re looking at what you would call negative-impact capital projects such as a transfer station or a landfill, and where they are placed,†says Broun, “they’re normally placed in or near low-income or predominantly minority neighborhoods.

“Then you look at positive capital improvements.†She cites, as examples, schools, senior centers and recreation facilities. “They’re normally not placed in predominantly minority neighborhoods.â€

Or: “Look at the placement of the library. Even the old library was in a predominantly white neighborhood, fairly affluent. Then look at the placement of the schools. There are no more schools left in the black neighborhoods of southern Orange County. … [A]nd it has both a social effect and an economic effect. Because realtors say, ‘Oh, you’re near Rashkis, you’re near Mary Scroggs, McDougal, elementary school number 10 — and that pushes the development there.â€

What Broun suggests, in sum, is public policy defined by class. And race.

Broun says she believes race probably played some part in the landfill/transfer station decisions that have been made over the past 35 years. But, she adds, “I think it was a combination of race and economics. It’s hard to separate; I think they are tightly wound together.â€

Neloa Jones agrees:

“I think that class certainly is an issue, but I think there’s an intersection of race and class. … [H]ad we been an affluent African-American neighborhood, I don’t think that they would be dumping it here — I don’t think any of this would have been here to begin with.â€

Robert Bullard, director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center at Clark Atlanta University and author of the book Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality, says, “There are very few instances where governments live up to their agreements when it comes to addressing disparities and inequities that they themselves created.

“And so in the case of the community in Orange County, what they are facing is basically a legacy of discrimination and a legacy of disparate impacts on a population that has too often borne negative impacts and oftentimes has been discriminated against when it comes to services that other communities take for granted.â€

These communities, says Bullard, are often “the last to get roads, sidewalks, the last to get streetlights, the last to get sewers and pipelines, etc. And so having a landfill placed on them and saying we’re going to do right by you 20 years from now, that’s laughable.â€

What’s one more?

Once you get a landfill, says Bullard, “it’s easier to get another landfill; and once you get three, it’s easier to get four. And once you get the landfills, it’s easier to get a transfer station. Because the thinking behind policymakers and elected officials who are in power to make those decisions is that you already have a landfill, so a transfer station won’t make a difference.â€

But, on Rogers Road, it did make a difference. It was the transfer station decision that stirred many at the forefront of this community resistance to become vocal and to take action — Neloa Jones among them.

As Jones began researching the history of the solid-waste facilities on Eubanks and of services provided or, more particularly, not provided to the community — including neighborhood enhancements that had been promised by local government back in 1997, she grew angry.

“And I probably talked about it so much — every meeting I would go to I would say, ‘I can’t believe Gertrude Nunn was excluded from getting water mains.’†(Gertrude Rogers Nunn’s home is on Eubanks Road, adjacent to the landfill.)

Furthermore, she asked, what about more comprehensive sewer lines and sidewalks and streetlights? These were things that had been repeatedly asked for and were as yet not forthcoming.

Nowhere in the vicinity

Jones says that, in her view, the community’s immediate objectives are, first, to stop the transfer station from being placed anywhere in the vicinity.

The second objective is that all homes in the community should have access to county water: “I really don’t understand why Orange County thinks we ought to pay for water connections.â€

The third objective is to close all waste facilities on either side of Eubanks Road that are now in operation.

There is, as well, a list of enhancements the community is calling for — some of which, still undelivered, were promised in 1997.

Foremost, though, Eubanks Road must be “taken off the table,†says Jones, as a potential transfer station site, “if for no other reason than that [this neighborhood] has already been on the table for 35 years, and that was longer than we were promised it had to be.â€

In the Dec. 13 issue of The Citizen: The transfer station reconsidered.