Chapter 2

THE AAF

THE Army Air Forces, successor to the Army Air Corps and forerunner of the United States Air Force, owed its designation to Army Regulation 95-5 of 20 June 1941. But it was a War Department circular of 2 March 1942, and in a more fundamental sense the war itself, which gave the new organization its peculiar qualities as a subordinate and yet autonomous arm of the United States Army--an arm which by the close of the war had emerged as virtually a third independent service. The history of this development is one of unusual complexity, and for students of institutional developments one full of interest.

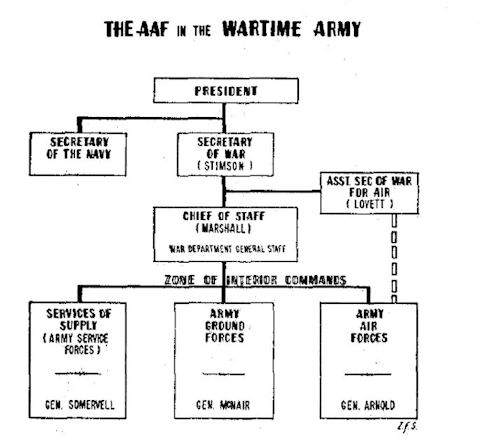

Officially, the AAF never became anything other than a subordinate agency of the War Department charged to organize, train, and equip air units for assignment to combat theaters. Its jurisdiction was wholly limited to the Zone of Interior, and it could communicate with air organizations in combat theaters only through channels extending up to the Chief of Staff, and then down through the theater commander to his subordinate air commander. The position of the AAF, in other words, was no different from that of the Army Ground Forces and the Army Service Forces, the other two of the three coordinate branches into which the Army had been divided. So, at any rate, read the regulations.

Actually, the Commanding General, Army Air Forces, as one of the three service representatives on the Joint Chiefs of Staff, functioned on a level parallel to that of the Chief of Staff. As a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, he moved at the very highest levels of command in the wartime coalition with Britain. He chose the commanders of the combat air forces, who well understood that he possessed as much power to break them as he had to make them.

--28--

With the air commanders overseas he communicated regularly, as often as not without reference to formal channels. Controlling the means necessary to implement operational plans in any theater, he exerted a powerful influence on the development of strategy, tactics, and doctrine wherever AAF units fought. He operated a world-wide system of air transport whose planes moved at his command through all theaters, the commanders of which were denied their traditional prerogative of controlling everything within their area of responsibility. Toward the close of the war, he even exercised direct command of a combat air force--the Twentieth. Throughout the war his staff functioned in a threefold capacity: it superintended the logistical and training establishment of the home front, advised its chief as a member of the high command, and helped him run the air war in whatever part of the world there seemed to be need for attention by Headquarters.

In drawing any such contrast as that above, one always runs the risk of overstatement. The contrast between theory and fact is so fundamental to an understanding of the AAF, however, that some exaggeration may be justified at this point for the sake of emphasis. Necessary qualifications will be noted in the following text, which attempts not so much to provide a detailed discussion of AAF organization as to suggest the broad outlines of its structure and the factors governing its relations with other military organizations.

Headquarters, AAF

Soon after Pearl Harbor it became clear that the Army's over-all organization was not suited to the requirements of war. Events, in short, had documented the AAF contention that only a fundamental reconstitution could solve the Army's problems. The coming of the war brought with it also, in the First War Powers Act of 18 December 1941,1 broad executive authority to effect necessary changes without further action by Congress.

The key figure in drafting the final plans was Maj. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, an Air Corps officer with considerable experience on the General Staff. Returning in December 1941 from a mission to England, McNarney first served on the Roberts Commission in its investigation of the Pearl Harbor disaster. But next, on or about 25 January 1942, he teamed up with Col. William K. Harrison, Jr., of WPD and Lt. Col. Laurence S. Kuter of the Air Corps to complete

--29--

an intensive survey already begun by them of War Department organization.2 Simultaneously, a team of air officers developed detailed plans for the necessary reorganization of the AAF, where there existed some sentiment in favor of an Air War Plans Division (AWPD) plan for equal air, ground, and naval forces operating under a small Presidential staff,3 somewhat along the lines fixed by British usage. The McNarney group, working swiftly, completed on 31 January a basic scheme which ignored this drastic proposal and depended instead upon the plan proposed by General Arnold in November 1941.* By 11 February Marshall ordered final drafts made. McNarney set up an executive committee with a blunt warning that it was not to be a "debating society," and rapidly shaped the necessary directives. Stimson and Roosevelt having approved the plans, on 28 February Executive Order 9082 directed that the new organization take effect on 9 March.4 Meantime, popular demand for action had been so vocal that Time, for example, predicted on 9 February that unless more autonomy for the air force was quickly provided "the hue and cry for a separate air arm . . . will go up again, louder and clearer than ever before."5

What Stimson called the formal recognition of quasi autonomy for air6 was achieved with the publication of War Department Circular 59 on 2 March 1942 (effective 9 March) outlining a new "streamlined" Army.7 The AAF now became one of the three autonomous commands into which the Army was divided. The Services of Supply (later, Army Service Forces) incorporated under one headquarters the varied logistical services of the Army and was responsible for providing all supplies and equipment, except such as were peculiar to the air forces. The Army Ground Forces (AGF) took over the training function of GHQ, which now was inactivated. Like AGF, the AAF was charged with a training mission, but it also carried an independent responsibility for supply and equipment peculiar to air operations. The three new commands were intended to relieve the General Staff of much of the administrative detail which formerly had burdened it, and thus to free it for service as an advisory body on general policy. With GHQ out of the way, the War Plans Division, forerunner of the powerful Operations Division (OPD), became the "command post"† through which the Chief of

* See above, pp. 26-27.

† The description is borrowed from Ray S. Cline's aptly titled Washington Command Post: The Operations Division (Washington, 1951).

--30--

Staff ran the Army, at home and overseas. In lieu of the three deputies who had been assisting the Chief of Staff, there was now to be only one deputy chief, a post going immediately to McNarney and to be held by him until October 1944. The reason for this choice was made clear a few months later when Eisenhower, urging McNarney's name for the theater command in Europe, learned that "to insure integration and to build up mutual confidence, General Marshall felt it essential that . . . his deputy should be from the Air Corps.8 Thus did Marshall seek to preserve unity of command while giving the AAF autonomy on the operating level and representation

at the top policy-making level. In only one way could it be argued that the AAF had lost ground: its commanding general was no longer a deputy chief of staff. But in the circumstances that mattered little.

The Air Corps, after March 1942, continued to be the permanent statutory organization of the air arm, and thus the principal component of the Army Air Forces. But the Office, Chief of Air Corps and the Air Force Combat Command were both abolished, their functions being assumed by AAF Headquarters. The dissolution of AFCC had been foretold soon after the outbreak of hostilities by developments which robbed it of any true function. Defense commands on the east and west coasts had been activated as theaters of operations, and the First and Fourth Air Forces had been assigned, respectively,

--31--

to their control.* Simultaneously, the Second and Third Air Forces found themselves committed primarily to a mission of training that was the concern of OCAC rather than of AFCC. The disbandment of the latter command eliminated at last the dual structure which had been a source of continuing confusion in the organization of the air arm since 1935.

According to WD Circular 59, the official mission of the AAF was "to procure and maintain equipment peculiar to the Army Air Forces, and to provide air force units" for combat assignment.9 In the inimitable manner of military directives, this prosaic phrasing masks the true dimensions of the task, which may be suggested by a few statistics, most of them bearing evidence of the ultimate accomplishment. A mere handful of professionals--there had been only 1,600 Air Corps officers in 1938--were spread thin to direct the recruitment, training, and equipment of a force which at its peak strength in March 1944 totaled 2,411,000 persons and made up 31 per cent of U.S. Army forces.10 In addition, the AAF employed up to 422,000 civilians, a maximum reached in October 1944. Expressed in terms of combat units, AAF goals rose from the 115-group program approved in January 1942, to the 224-group objective set up in July, and then to the maximum 273-group program adopted in the following September.† On paper 269 groups had been formed by the close of 1943, but rescheduling reduced the actual peak to a total of 243 in April 1945, of which 224 groups were then deployed overseas. The composition of the 243-group force shows the direction of the AAF effort: there were 26 very heavy bombardment groups, 72.5 heavy bombardment groups, 28.5 medium and light bombardment groups, 71 fighter groups, 32 troop carrier groups, and 13 reconnaissance groups. AAF personnel assigned overseas reached the figure of 1,224,000 in April 1945, with 610,000 deployed against Germany, 440,000 against Japan, and the remainder assigned to air transport duties or at scattered outposts. Altogether, up to V-J Day the AAF took delivery on 158,880 airplanes, including 51,221 bombers and 47,050 fighters. Maximum aircraft strength at any one period was reached in July 1944, at which time there were 79,908 aircraft (excluding gliders). The combat air forces, thus equipped, dropped 2,0S7,000 tons of bombs on enemy targets--threefourths

* See below, p. 72.

† See Vol I, 251, and below, pp. 279-87.

--32--

of it against Germany--and fired 459,750,000 rounds of ammunition. Altogether, 2,363,800 combat sorties were flown, 1,693,000 of them against Germany. Personnel casualties of 121,867 included 40,061 dead (17,021 of these were officers). Aircraft losses on combat missions came to 22,948 planes. The cost of the effort, in direct money expenditures by the AAF from mid-1940 to V-J Day, was $38,345,000,00011--over one-tenth of the total direct costs of the war to the United States.

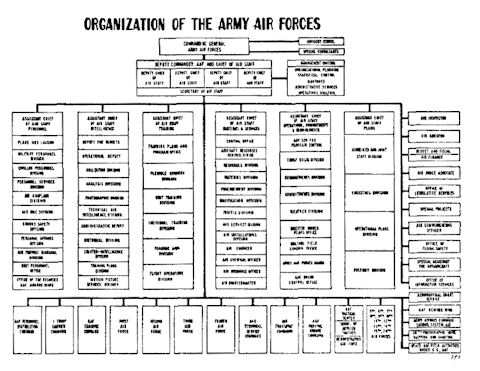

Although many different organizations, and by no means all of them AAF units, contributed to this gigantic effort, the fullest reponsibility fell upon Arnold and the reorganized Air Staff at AAF Headquarters. That staff, though it could claim descent from the Air Service of World War I through the Office, Chief of Air Corps, for all practical purposes had its origin in June 1941, when the Plans Division of OCAC provided the nucleus of A-staff sections to advise the newly created Office of the Chief, AAF.12 The Air Staff thus established was supposed to function at a policy-making level, with decisions to be implemented through OCAC and AFCC. Acute dissatisfaction with the division of authority inherent in this tripartite organization had led the McNarney committee to decree a consolidation of the functions in one staff. But the committee clung to the

--33--

belief that there would be an advantage in maintaining a distinction between policy-making and operating sections of the single staff. Perhaps this distinction was maintained because the reform simultaneously planned for the General Staff depended to some extent upon the same division. Or perhaps the influence of the RAF should be chiefly credited, for its system of directorates had greatly impressed American observers, and fully two months before the March 1942 reorganization the AAF had set up test directorates for study of the RAF organization13 Whatever the reason, the AAF was

directed to establish separate policy and operating staffs for control of the subordinate commands through which the Army's aviation objectives would be accomplished:

Under the new organization, policy would be determined by A-1 (Personnel), A-2 (Intelligence), A-3 (Training and Operations), A-4 (Supply), and Plans, which toward the end of the war was sometimes designated A-5. The Air Inspector was also put on this level. The policy staff was to schedule the programs of the AAF, with synchronization entrusted to Plans, which thus became and remained the key office in AAF Headquarters. Through the work of this part of the staff detailed requirements would be established for guidance of the operating staff, which was built around four directorates: Personnel, Military Requirements, Technical Services, and Management Control. As these titles suggest, each of the first

--34--

three offices was intended to provide centralized direction of a variety of activities which bore on the successful performance of a major function of the AAF, while the fourth centralized the organization of special agencies designed to assure proper coordination of the total effort. Advocates of the plan had been inclined to talk in terms of "total patterns," and to argue that the traditional plan of organization tended to encourage in any one office too much concern for the performance of a primary mission, such as training, with resultant failure to consider all related problems. The operational staff of 1942 included such traditional offices as those of the Air Surgeon and the Air Judge Advocate. But these did not enjoy the status of the four directorates, which embodied the heart of the plan. Though one of the directorates, that of Personnel, closely followed conventional conceptions, the others showed a difference that will justify some attention to detail.

The clearest evidence of the attempt to apply a concept of "total patterns" to the problem of administration is perhaps provided by the Directorate of Military Requirements. Its subordinate divisions were headed by Directors of Air Defense, Bombardment, Ground Support, War Organization and Movement, Base Services, and Individual Training. Each of the first three directors--of air defense, bombardment, and air support--was expected to act as a coordinating agent in the solution of problems affecting tactics, equipment, and training in his own special field of combat operations. For the accomplishment of this end he could deal with other directors in his own office, such as the Director of Individual Training, or with any other office whose function might affect the solution of a particular problem; his job, in short, was to see to it that all related activities moved apace toward achievement of the goals set by the policy staff in the area of his administrative responsibility. War Organization and Movement, originally planned as a separate directorate, directed the assembly of task forces, prepared troop-movement orders, and allocated aircraft and personnel. The Director of Base Services inherited a complex group of functions which included the allocation of supplies, the determination of technical standards for air bases and facilities, the supervision of air transport, the planning of military air routes, and the maintenance of necessary liaison with other arms and services. The Director of Individual Training worked chiefly with the training commands to assure the maintenance not

--35--

only of standards but of balance in the more basic phase of the training program14 No comparable provision was made in March 1942 for supervision of the more advanced phase of training. As an afterthought, in May unit training was made a "primary obligation of the entire Air Staff," with responsibility centered in A-315

A second group of offices, joined together under the Director of Technical Services, dealt with a variety of specialized problems reflecting not only the increasing dependence of aviation on technical aids but also the tremendously enlarged scale of the AAF's operations. Some of the functions had previously developed within OCAC, but other offices were quite new to any U.S. military headquarters. Already, the very size of the air arm's expansion had produced critical problems of traffic congestion and control, problems which required new attention to the regulation of military traffic in coordination with appropriate civilian agencies and in addition introduced a factor of increasing importance in determining the location of additional air installations. For traffic control, and even more importantly, for the direction of combat operations, there were in the field of electronic communications new developments whose vital importance had been clearly established in the Battle of Britain. It had also become clearer than ever before that the success of air operations depended upon accurate forecasts of weather conditions the world over. The AAF faced its global responsibilities, moreover, at a time when much of the world remained to be charted and mapped with the aid of aerial photography and for the special guidance of the airman. And so largely did air operations depend upon technical equipment that normal military inspection had to be supplemented by special inspections by men who had technical knowledge. Consequently, the Directorate of Technical Services included directors for Communications, Weather, Photography, Technical Inspection, and Traffic Control and Regulations. This last was divided in May 1942 into the Directorate o£ Civil Airways and the Directorate of Flying Safety.16

The Directorate of Management Control represented a significant attempt to apply some of the methods of modem business to a large military organization. Since the beginning of the Air Corps' expansion in 1939 it had become increasingly evident that older methods of reporting and inspection, however well suited to the needs of the smaller air arm of the 1930's, could not provide the information and

--36--

the degree of over-all control that was essential to a properly functioning headquarters. Early in 1941 the OCAC Plans Division had established an organizational control and administrative unit for the correlation of statistical information and for study of organization and procedures within the Air Corps. A statistical section was added at the Air Staff level in June 1941, but its statistics, as one might expect, did not always agree with those compiled in OCAC or AFCC. In the fall of 1941 Col. Byron E. Gates established in the Plans Division an administrative planning section employing civilian administrative analysts who were authorized to review Air Corps procedures and to recommend correction of any deficiencies found. This action received a strong indorsement in a study completed in November 1941 by a firm of management engineers, the Wallace Clark Company, whose survey emphasized the need for better statistical reporting, standardization of administrative procedures in accordance with the latest business practices, and the development of new techniques for control of all phases of the air program.17 It was against this background that the March 1942 reorganization brought together under Management Control the Directors of Organizational Planning, Statistical Control, Legislative Planning, and, in addition, the Air Adjutant General.

At the center of the new Management Control stood the two offices of Organizational Planning and of Statistical Control. The former studied administrative procedures and prepared flow charts of AAF activity with a view to recommending necessary reforms or reorganizations; it also coordinated all administrative publications. Statistical Control undertook to consolidate and systematize all statistical reporting so as to provide for staff purposes information that was not only full but which facilitated comparative studies. For this last purpose, it was necessary that the data be based upon a uniform system of reporting. The methods employed are perhaps best suggested by the newly developed AAF Form 127, which became the basic report for statistical information on personnel. Required at regular intervals from all AAF units, this form reported all personnel both by military specialty and unit assignment. Prepared in multiple copies for transmission through channels, the report gave some assurance that all echelons of command would base their studies on the same statistics. By providing comparable data for every unit of the AAF, Form 127 greatly facilitated the preparation

--37--

of over-all analyses. Similarly, the daily inventory of aircraft (AAF Form 120) was used as a source of information for determining advance requirements as well as the most effective distribution of equipment on hand. During the latter half of the war Statistical Control undertook through AAF Form 34--a report listing for each mission such items as the number of planes employed, the flying time, the bomb tonnage dropped, the total of ammunition and fuel consumed, and the losses sustained or inflicted--to replace fragmentary and uneven reports from combat theaters with uniform world-wide operational statistics. A special dividend for historians came at the end of hostilities in the Army Air Forces Statisrical Digest, a publication of December 1945 which summarized in as accurate and complete a form as can be hoped for the statistical record of the war years.18

As the work of Management Control suggests, the Air Staff displayed from an early date a marked inclination to borrow heavily from the experience and skills of the civilian community it served. This is explained in part by sheer necessity, a necessity which affected all of the services in their attempts to keep up with programs of expansion quite literally conceived on unprecedented scales. But no other arm or service expanded during the war years at the rate forced upon the AAF. With a mere handful of regular Air Corps officers and a thousand different places at which their experience was at a premium, only a few of them could be held for staff work at Headquarters. This was especially true after the spring of 1942, when the demand for experienced leadership in newly forming combat commands drew heavily upon the small staff of regulars who had shaped the Air Corps' expansion from 1939 through 1941.* Other branches of the Army helped to make up the deficiency, but the expanding staff at Headquarters necessarily recruited its strength mainly from civilian life. Some of those recruited were veterans of World War I, some had experience with the Narional Guard, some were reservists of one arm or another, some were regulars called back from retirement, and some enjoyed the limited advantages of a peacetime ROTC course of study in college. Many were commissioned directly from civilian life without any military background

* For example, Faker, Spaatz, Kuter, and Hansell transferred their attention to combat operations against the European axis in 1942, and General George took the responsibility for a rapidly developing air transport system.

--38--

whatever, and some of the more influential elected to remain in a civilian status. But whether in uniform or out of it, staff members took up their tasks with points of view that were only here and there colored by any long association with military usages. At the top of any office one usually found a regular--and usually, let it be said, a man who knew how to get along with civilians--but below that level there were multiplying opportunities for speculation on whether the colonel was in "real life" a Buffalo lawyer, a Cleveland executive, a California politician, a New York public relations counselor, or just a college professor.

The very novelty of many tasks thrust upon the AAF encouraged heavy borrowing from the experience of nonmilitary organizations. There was, for example, no military model or parallel for the development of a world-wide system of air transport, but the experience of the civilian airlines constituted a source of talent that was drawn upon heavily. It should be noted, however, that experience in a civilian type of activity could be a limiting factor on the usefulness of an individual unless he was able to adjust his thinking to the special demands of a military effort. Thus, the Air Transport Command faced many of the problems of any other airline, but in the speed of its development, in the scale of its operations, and in its emphasis on the movement of freight rather than passengers, it was definitely unprecedented. Similarly, the air service organizations of the AAF encountered many of the problems of a giant industrial concern, and could use profitably, for instance, methods and techniques developed by American industry for stock accounting on some 600,000 different items of equipment and supply. But cost rationales which shaped the pattern of business procedures had to give way to new concepts founded on military urgency. A railroad executive might prove most helpful to an intelligence office plotting a bombing campaign against enemy transportation systems, but only if he could think in terms of the factors which govern a military, as distinct from the normal, employment of railway facilities. An educator, to mention one other example, could bring valuable experience to the problems of training, but he too had to make drastic adjustments in older habits of thought. The very scale of the AAF training program and the schedules it had to meet demanded the fullest exploration of new techniques for the classification and instruction of students. For the academician, perhaps the most drastic adjustment of all was to get

--39--

away from a sense of the limitations normally imposed on educational methods by academic budgets.

Fortunately, the AAF itself was predisposed in favor of an experimental approach. Though its top leaders were in most cases West Point graduates, their long identification with the Air Corps, which had regarded itself as the victim of an entrenched conservatism in the General Staff, encouraged a view of themselves as advocates of new approaches to military problems. Though the youthfulness of the AAF's generals was much overplayed in the popular mind, the organization itself was new and its attitude was basically youthful, in the sense of not being overly bound by conventional ways of doing things. This was in part due to the outlook of the aviators, who at all echelons of the AAF occupied the key positions. The pilot, whatever his limitations when outside the cockpit, owed the very existence of his vocation to a revolutionary technological development that obviously had not yet run its full course. He had been closely associated with experimental developments in aeronautics and had shared with many men outside the Air Corps the excitement of new achievements in this field. He was thus conditioned by experience to accept the proposition that the United States Army had no monopoly of useful knowledge.

The American airman entered the war with a rather well-developed body of doctrine on how the airplane should be employed. In addition to its role in support of other arms, air power, he believed, had its own independent mission. That mission emphasized the capacity of the airplane to strike directly, given the necessary bases, at the enemy's "national structure" for the purpose of destroying both his will and ability to wage war; it was also understood (and the earliest operational experience in the Pacific tended to stress the point) that to get at the "national structure" it would first be necessary to win control of the air by defeating the enemy's air force.* The accomplishment of this preliminary objective may have seemed at the outset to call for nothing more than the necessary forces and for intelligence in their employment, but it was evident from an early date that the AAF was poorly prepared for waging a strategic campaign against Germany, or any other enemy, because of the paucity of organized intelligence on the target itself. Prewar attempts to set up priorities for certain Categories

* See especially Vol I, 51-52, 40.

--40--

of targets stood the test of combat surprisingly well,* but experience had brought an early appreciation of the need for a more scientific approach to the problem of target selection. A notable step in this direction came in December 1942, when a special Committee of Operations Analysts (COA) was established by Arnold's order in Management Control.19 The designation actually was intended as a cover; for the committee, whose true function was target selection, was concerned only incidentally with the analysis of operations. Two features of its organization and procedure merit special note: it combined regular members of such staff offices as A-2 with a distinguished group of civilian experts, and its investigations represented a conscious attempt to apply scientific procedures to the problem of target selection. The committee borrowed heavily from the resources of a variety of intelligence agencies, both British and American, but the Combined Bomber Offensive plan adopted as a guide to the Eighth Air Force's expanding strategic operations against Germany owed its essential character to the work of COA.† In the spring of 1943 the committee, somewhat enlarged to provide representation for the Navy, turned its attention to a study of Japanese targets in preparation for the B-29 offensives.‡

As the war progressed, it became increasingly evident that the scientific analyst had a no less important part to play in the development of combat tactics. This was particularly true of strategic bombing operations, where the need for a check on the effectiveness of any one mission, or of a particular tactic employed, early led to provision for consolidated reports which presented with increasing fullness pertinent operational data on missions flown. As early as October 1942, civilian experts trained in statistics and other analytical disciplines had been put to work by the Eighth Air Force in the Operational Research Section,§ whose designation and function had been adapted from the practice of the RAF.20 Every mission in a hitherto uncharted field of warfare, experience showed, was in greater or lesser degree an experimental venture to which the techniques of quantitative analysis could make a well-nigh indispensable contribution.21 Not every combat commander was as prompt as Eaker had been to sense the importance of operations analysis. Some were inclined instead to rely on a general rule of hitting the enemy somewhat indiscriminately with

* See Vol. II, 368-69.

† See Vol. V, 26-27.

‡ See Vol. II, 348-67.

§ See Vol. II, 225.

--41--

"everything in the book."22 But Arnold, who became fond of admonishing his staff that the "long-haired boys" could help, established an operations analysis section in Management Control at AAF Headquarters in October 1943 under the leadership of Col. W. Barton Leach, a peacetime member of the Harvard law faculty.23 Through this office other air forces were encouraged to take advantage of evaluation techniques that had been more familiar in the laboratory than on the battlefield but to which Arnold paid a warm tribute after the war.24

In running thus ahead it is not intended to suggest that the basic organization of AAF Headquarters had been permanently fixed in the spring of 1942. On the contrary, there had quickly developed a strong and growing dissatisfaction with the fundamental principle on which the staff at that time had been organized. A-staff sections tended to complain that they were hampered in their efforts at shaping policy because they lacked information on current operations; the directorates objected that failures in planning all too frequently put them into the business of policy-making "according to their individual ideas."25 Many came to suspect and then to be convinced that the distinction between policy and operating staffs was an artificial one. They found coordination difficult because of trouble in pinning down ultimate responsibility. Field agencies, too, complained that the organization was complex and confusing. In July 1942 the First Air Force attributed twenty-five instances of misinformation received by it to the confused channels of the Washington headquarters. Other field organizations protested that the policy of decentralized responsibility for operations was being defeated by the tendency of the directorates to give orders in too great detail. Lovett called a special meeting in September 1942 which resulted in some adjustments. Management Control was given policy-staff status at that time, and several offices--those of the Air Inspector, Air Judge Advocate, Air Surgeon, Budget and Fiscal, and the Director of Flying Safety--were designated as special staff sections. But these adjustments did not strike at the root of the difficulty, and dissatisfaction continued. Detailed studies at Headquarters, supplemented by suggestions brought back by General Arnold from a world tour, led to a major reorganization.26

The new plan, which went into effect on 29 March 1943, abolished the directorates and combined policy-making with the control of operations in reconstituted A-staff offices. It was expected, however,

--42--

that the degree of operational control exercised by Headquarters would be reduced to a minimum. The AAF program on the home front was approaching its peak, and the need for greater decentralization of controls had undoubtedly contributed to the decision to reorganize. Arnold warned the newly arranged staff that it "must stop operating" in order to concentrate its energies on the development of clear-cut policies that would tell subordinate commands what to do and sometimes when to do it, but never how to do it.27 Most of the surviving Headquarters organizations were now regrouped under one of six offices, each headed by an assistant chief of air staff: Personnel; Intelligence; Training; Materiel, Maintenance, and Distribution (MM&D); Operations, Commitments, and Requirements (OC&R); and Plans. Management Control, the only one of the original directorates to survive the reorganization, was attached directly to the office of the Chief of Air Staff to assist him in his duties as the head of administration under Arnold. In the shift Management Control lost its legislative planning function but acquired a Manpower Division charged to eliminate overlapping within the AAF of agencies concerned with personnel functions. In August 1943 the Administrative Services Division took over many of the duties formerly performed by the Air Adjutant General, and in October, as previously noted, Management Control acquired an Operations Analysis Division. Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, who had presided over the studies which gave shape to the new organization, continued to serve as Chief of Staff for a few more weeks prior to his assignment to a combat command in CBI during the summer of 1943. His place was taken by Maj. Gen. Barney M. Giles. There were three deputy chiefs of staff in 1943, and four from 1944 on.

The six assistant chiefs of staff held responsibilities that were reasonably well indicated by the names of their several offices. AC/AS, Plans, under Brig. Gen. Laurence S. Kuter, who took command in the summer of 1943, became even more influential than it had been before. Having served with the 1st Bombardment Wing of the Eighth Air Force and having more recently participated in the moves leading toward the establishment of the Northwest African Air Forces, Kuter was one of the first key AAF officers to be brought back from a combat zone for an important assignment at Headquarters. Under Kuter AC/AS, Plans gave multiplying evidence in its major activities of the fundamental shift of emphasis which came in the AAF's war effort

--43--

with the year 1943. Theretofore, planning at Headquarters necessarily had centered on the problems of recruiting, training, equipping, and organizing the forces with which to fight. But as the training program, for example, reached and passed its peak in 1943, Headquarters directed its own energies increasingly to the support and, not infrequently, to the direction of combat operations overseas. No organizational chart quite managed to convey a sufficiently strong impression of the central importance of AC/AS, Plans. Its staff, though strengthened

by the addition of officers who had fulfilled their quota of combat missions overseas and who knew at first hand combat conditions in the several theaters, remained small. But it was well understood throughout Headquarters that Plans operated closer to the center of power than did any other parallel office. Its theater sections, not to mention the special JCS section, which held custody of Arnold's records as a member of the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff, served to remind those who needed the reminder that Arnold's command was not restricted to the Zone of Interior.

OC&R took over many of the duties of the former Directorate of Military Requirements, but its job was more sharply defined. It superintended the Proving Ground Command in Florida, where tactical

--44--

equipment and tactics themselves were tested under simulated battle conditions. It was responsible for the School of Applied Tactics, also in Florida, for the special problems of the Antisubmarine Command during its short and troubled history, and for the Flight Control Command. But the burden of its job was superintending the organization and movement of air units overseas; for all the varied units which made up an air force it set up standard tables of organization and equipment. To accomplish its ends, the office had to work closely with OPD in the War Department. Similarly, AC/AS, Personnel had repeated occasion to coordinate with G-1. AC/AS, Intelligence devoted itself to the collection, evaluation, and dissemination of information bearing especially on the problems of air warfare. It also controlled counterintelligence activities within the AAF and the AAF's historical program. AC/AS, Training gave centralized direction to the Flying Training and Technical Training Commands, and to the training activity of I Troop Carrier Command and the four continental air forces. MM&D, which became AC/AS, Materiel and Services on 17 July 19, was the Headquarters office for the Air Service, Materiel, and Air Transport Commands. Charged with special responsibility for equipment and supplies peculiar to air units, it worked closely with Army Service Forces on many questions of common interest and dispute, including those involving the so-called common use items of supply.

As usual, there were a few somewhat specialized functions which could not be readily fitted into the general scheme of organization, or which for a particular reason needed to be kept close to the top level of command. The accompanying chart indicates their several designations. Three new special staff offices were added in October 1943: Flying Safety, a Headquarters agency for the Office of Flying Safety at Winston-Salem, North Carolina; a Special Assistant for Antiaircraft; and the Air Communications Officer, whose duties were enlarged after October 1944, when the AAF took over from the Signal Corps responsibility for developing and maintaining air communications equipment. In December 1943 the Office of Legislative Services was also added for liaison with Congress and to review proposed legislation affecting the AAF.28 Except for a subsection in the War Department Public Relations Office, the AAF had gone without a PRO of its own, but a Technical Information Division under AC/AS, Intelligence had served partly to plug the gap. This division was separated

--45--

from Intelligence and elevated to special-staff status in the spring of 1944, and in November it was redesignated the Office of Information Services.29

With little significant change the organization established for AAF Headquarters in the spring of 1943 served until after the war. No military headquarters, of course, can long endure a continuing dependence on an old T/O; the redrawing of organizational charts and the reshuffling

of familiar functions seem an almost indispensable part of the military way of life. But the changes made after March 1943 had their principal effect on the internal structure of the several offices, and many of them were of slight importance. Of more significance was the continuing effort to reduce the load carried by Headquarters through consolidation of subordinate commands reporting to Washington, as in the creation of a single Training Command in 1943, in the union of materiel and service agencies under the Air Technical Service Command in 1944, and in the establishment of the Continental Air Forces in May 1945.*

--46--

Even so, Headquarters still displayed the normal tendency of government agencies to grow. Contributing to this expansion were some instances, no doubt, of empire-building, but there were more important causes. Considered simply as an organization whose task was to recruit, train, and equip forces for combat, the AAF reached the peak of its operations in the winter of 1943-44, and the burden falling upon Headquarters should have tapered off thereafter. But this was far from being the case. Indeed, the moves instanced immediately above to lighten the responsibility for Zone of Interior activities served chiefly to free Headquarters for attention to other pressing business. With the acceleration of combat operations in all quarters of the globe and with multiplying demands upon Arnold for the means to exploit developing opportunities, AAF Headquarters increasingly assumed the responsibilities of an office exercising very real prerogatives of command over world-wide operations. On the constitution of the Twentieth Air Force in April 1944, AAF Headquarters literally doubled as the operating headquarters for the new force,* and much of the energy which had made a success of the B-29 "crash program" was generated by Arnold's staff. Moreover, the fact that the war had to be won first in Europe and then in the Pacific forced Headquarters to give painstaking attention to complex problems in the redeployment and the reequipment of units after V-E Day. And withal, the changing status of the AAF vis-a-vis its sister arms and services, not only added to the complexities of day-to-day procedures but also raised new questions of policy in long-range planning. There was work enough to do.

It is difficult to determine a proper standard against which to judge the quality of staff work at Headquarters. Examples of confusion, of overlapping jurisdiction, of waste, of empire-building, and of personal failures to measure up to requirements would be easy to point out. But how much this would prove is debatable, for all such instances could be balanced and more than balanced by contrary examples. There were critics at the time who felt that the AAF never quite whipped the problem of establishing effective controls over its diversified programs; a Program Control Office functioned in OC&R, but it was felt that this office should have been placed on a higher echelon.30 This may well have been true. But the final test would seem properly to be the measurement provided by over-all accomplishment, and on

* See below, p. 55.

--47--

that score the verdict has to be favorable. Neither this nor any other headquarters could claim to have won the air war, but it must be admitted that AAF Headquarters was in a peculiarly strategic position to make a major contribution to losing it. Instead, Arnold's staff, beginning in 1938, gave shape to programs, not only unprecedented in scale but lying largely in hitherto uncharted fields of warfare, that stood the test of battle remarkably well. They were also completed on schedule, as nearly as anyone reasonably could have asked. Moreover, the AAF, while contributing significantly to two great military victories as one member of an interservice team, did so without sacrificing progress toward the achievement of its own distinct ambitions. This record on its face suggests staff work of high quality.

Topside Relations

Before turning to the channels through which the AAF accomplished its primary mission, there may be some interest in retracing the steps by which it won recognition as virtually a third independent service. That status, as previously noted, had no recognition either in law or in the War Department regulations which defined the basic relationships of the constituent parts of the Army. The chief of these regulations, that of 2 March 1942, could have been read to mean that the AAF had been limited, at least for the duration of the war, to a subordinate role. At the very time of its writing, however, the head of the AAF had already attained a position in the top war command that profoundly affected the status of the organization he represented. Fortuitous circumstances were partly responsible, the chief of them being that the British had adopted a threefold division of their armed services-air, ground, and sea--as the basic principle governing their military organization. That fact, plus the inescapable importance of air operations in all existing war plans, argued strongly for representation of the chief U.S. air arm among the top military advisers to the Commander in Chief, especially when consultations were held with the British Chiefs of Staff. This necessity had been foretold as early as the Atlantic conference of August 1941, when Arnold accompanied Roosevelt to his historic meeting with Churchill. When Churchill and the British chiefs came to Washington just after Pearl Harbor for consultation with Roosevelt and his advisers, Arnold again was given an important part in the discussions. As he himself later put it: "From that time forward, there was no doubt about the Commanding General

--48--

of the Army Air Forces being a member of the President's Staff."31

These discussions of December 1941--January 1942 quickly took on a pattern destined to be followed subsequently, as Arnold joined the Chief of Staff and the Chief of Naval Operations in consultations on proposals from, or to be made to, the British chiefs in combined sessions.* At the suggestion of the British on 10 January 1942, it was agreed to establish a permanent inter-Allied organization representative of the military staffs of the two nations.32 Out of this proposal came the Combined Chiefs of Staff with permanent headquarters in Washington, where the British chiefs normally depended upon representatives assigned for the purpose. The public in both countries gained their knowledge of the organization chiefly through the major high-level conferences of 1943-45, attended by both Roosevelt and Churchill, at which the two groups of staff chiefs consulted on major issues of strategy and resources. It was through the permanent organization, however, and especially through the work of its subordinate committees, that the ground was cleared for those agreements which made of the Anglo-American war effort an unprecedented example of a successful military coalition. But the purpose here is not to describe the development of an extraordinary experiment in international relations, but to point out the significance of the fact that the AAF enjoyed representation at this top level of command on a par with the RAF and, for all practical purposes, on a par with the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army.

The CCS by its very existence virtually made inescapable some new organization of the U.S. chiefs of staff. That need was met by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, whose formal meetings dated from 9 February 1942. It would be a mistake to assume that the JCS owed its existence solely to the need for consultation among the American chiefs in preparation for sessions with their British counterparts, for the conditions of modern warfare imposed upon all services a new necessity for the closest cooperation. Undoubtedly, the Joint Board, prewar agency for coordination of Army and Navy activity, would have undergone some significant development of function even had there been no close alliance with the British. Whether the AAF in such a development would have promptly won representation comparable to that of the Army and the Navy is another question; but it

* See Vol I, 237 ff.

--49--

did win such representation on the JCS and on the subordinate committees which paralleled in function and organization those of the CCS. That President Roosevelt appreciated the significance of this fact was made clear in a letter he wrote to Senator McCarran in 1943: "My recognition of the growing importance of air power is made obvious by the fact that the Commanding General of the Army Air Forces is a member of both the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff."33

The success of the Joint Chiefs came from a "will to agree," rather than from any clear definition of powers or of procedures. It would be misleading to speak of Arnold as having a vote; what he had was a voice in the discussions through which agreement was reached. Adm. William D. Leahy, who in the summer of 1942 was made a fourth member as the President's personal chief of staff, later described the Joint Chiefs as "just artisans building definite patterns of strategy from the rough blueprints" of the Commander in Chief.34 But day-by-day planning often molds ultimate strategies, and the joint Chiefs were in a very real sense the coarchitects, with their British colleagues, of the plans which produced victory. Robert Sherwood, in Roosevelt and Hopkins, has suggested the role of the joint Chiefs in this passage: "Churchill soon learned that if he wanted to influence American strategic thinking, as he often did, he must do his arguing with the generals and admirals."35 Among those he had to persuade was Arnold.

Perhaps too much stress can be placed on the simple fact of Arnold's membership in the JCS. In any event, he undoubtedly would have had representation in the work of JCS agencies, just as did Navy airmen on the joint and Combined Staff Planners,* the key committees for strategic planning.36 Not only would he have had such representation, but there is reason to believe that the attitude then prevailing in the War Department, which showed an increasingly marked contrast to Navy opinions with reference to its own air arms,37 would have assured for him an influence comparable to the importance of the arm he commanded. Since the fall of 1940 he, or his chief of staff, had presided over the Joint Aircraft Committee, the earliest forerunner of the system of combined staff agencies. Its critically important function of allocating U.S. aircraft production among the several

* It should be noted, however, that the presence of Navy airmen served partly to preserve a balance between Army and Navy representation which seems to have been important to the Navy Department.

--50--

claimants, including the British and the Russians, became even more important with the U.S. entry into the war and as the committee's duties were absorbed by the Munitions Assignments Board established in February 1942, with powers over British as well as American production.* Already at that time Arnold had hammered out an agreement with ACM Sir Charles Portal on the relative claims of the RAF and AAF that was accepted by the new board as a basis for production planning.† In short, the central importance of aircraft to U.S. war plans had long since given to Arnold a place, however ill defined, among the top commanders.

At the time of the War Department reorganization in March 1942, it was planned that the General Staff henceforth should be evenly divided between ground and air officers. This objective was never realized, apparently at the election of the AAF itself,38 but the number of AAF officers assigned to duty with the General Staff did increase to a point that an organization such as OPD acquired something of the character of a joint staff agency.39 Col. St. Clair Streett became one of the two deputy chiefs of OPD under Eisenhower in the spring of 1942 and later in the year (then a brigadier general) served as chief of OPD's influential Theater Group, a post assumed in the fall of 1944 by another air officer, Maj. Gen. Howard A. Craig.40 Such assignments, like that of McNarney as Marshall's deputy, gave expression to the latter's hope that special representation for the air force might be combined with unity of command. AAF Headquarters was thought of as an expert staff for the advice of the General Staff on questions affecting air operations, but the power to issue operational directives lay in the jointly manned OPD, which in turn looked to the AAF for implementation of directives issued with its advice. The AAF was thus bound to clear through OPD its own decisions on such matters as the assignment and movement of air units overseas.

It was through OPD also that the AAF got at least some of its representation on JCS agencies. This point, however, can be too finely drawn. In the early development of the JCS machinery, circumstances and practical needs had more to do with the organization and functioning of the several committees, many of which were ad hoc in origin, than did any directive, fundamental charter, or like paper. There was a job to be done, the pressures to get on with it were great, and no

* See Vol I, 129, 256-57, and below, pp. 292, 404.

† On the Arnold-Portal agreement of 13 January 1942, see Vol I, 248-49.

--51--

onequestioned that Arnold should be represented in discussions affecting his own arm, as indeed did practically every question before the Joint Chiefs. If the air officers attending a committee meeting came from OPD and at its direction, as in the Joint U.S. Strategic Committee,41 their presence conformed more closely with the legal basis of War Department organization in 1942. But rules on membership in the committees, insofar as rules existed, tended to be very flexible. The working members of any committee were as likely as not to be representatives of the staff offices immediately concerned with the questions at issue.

It should be noted, too, that the influence of JCS organizations on the shaping of policy and strategy was not so great in 1942 as it later became.42 Marshall himself carried much of the burden, as is suggested by his two personal missions to England in April and July of that year (the second time accompanied by Admiral King) in quest of an agreement with Britain on operations against Germany. If Marshall depended chiefly on OPD for the staff work to lighten his burden, he also leaned heavily on Arnold in ways that tended to emphasize not so much the subordination of Arnold's staff to OPD as it did their parallel responsibilities. In the forces which the United States could promise to commit in support of its argument for an early offensive against Germany no other element loomed larger than did the air component which Arnold bent his every energy to get deployed as quickly as possible.* When the decision went against Marshall and plans for a North African operation threatened to undermine the whole concept of an initial concentration against Germany, the issue turned largely on a question of air deployment. It was settled, as Marshall had hoped to have it settled, on the basis of information provided by Arnold and Streets, then chief of OPD's Theater Group, as the result of a special mission to the Pacific theaters in the early fall of 1942.† In the long and bitter conflict which developed between the AAF and the Navy over the employment of land-based aircraft against German submarines, AAF Headquarters, OPD, and Secretary Stimson's own office worked in the closest collaboration without

* This is not to overlook Arnold's own interest in seizing the best opportunity he had to mount a strategic bombing offensive. The whole subject of strategy and deployment against Germany has been discussed in Volumes I and II.

† See the admirable discussion of this entire question in Maurice Matloff and Edwin M. Snell, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare, 1941-1942 (Washington, 1953), especially pp. 320-23.

--52--

much regard for channels, except that Stimson and Marshall lent their every aid in pressing upon King the advantage that might be gained through adopting doctrines developed by the AAF.* Other examples might be noted here, but perhaps enough has been said to support the proposition that the War Department was coming to rely on two policy-making staffs. The one staff was more specialized than the other, but it was hardly so subordinate to the other as regulations and standard procedures might suggest.

When the U.S. chiefs undertook to strengthen the organization of the JCS after an unhappy experience at the Casablanca conference of January 1943 had demonstrated the superiority of British staff work,43 the AAF scored additional gains. Membership in the Joint Planning Staff (JPS), which continued to serve as the key committee through which the work of other committees was channeled to the JCS, came in the spring of 1943 to have a fixed identification with particular staff offices in the two services, Arnold being represented by his AC/AS, Plans.44 The point may be a small one, but it is worth noting that Arnold was represented in the same way as was Marshall, for whom the chief of the OPD Strategy and Policy Group regularly spoke. Three of the six officers designated by OPD for service as planners under the newly established Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) were air officers; what is more significant, these three were shortly transferred out of OPD to AC/AS, Plans.† The committee itself functioned under the leadership of three senior planners, or directors, representing the Army, Navy, and A. Its charter indicated equal representation below this level for the Navy and the Army, including its air force, but JWPC "actually conducted most of its business on the principle that there were three separate spheres of special knowledge, as represented by the three directors."45 On other committees of the JCS, which served with their British opposite numbers to provide the organization through which the CCS worked, the AAF henceforth also enjoyed what could be described as independent representation.

This fact has a significance transcending mere questions of War Department policy, important as that was for its effect on the AAF's position. A major result of the greatly strengthened organization of

* See Vol I, Chap. 15, and Vol. II, Chap. 12.

† Compare above, p. 52, the earlier rule with reference to the Joint United States Strategic Committee.

--53--

the JCS was to give into its hands a far greater control over the deployment and operations of U.S. combat forces than theretofore. In the earlier part of the war the JCS and its committees had served perhaps chiefly for the clarification of differences that were finally resolved through correspondence or by verbal agreement between Marshall and King, who had an unmistakable and understandable preference for dealing with Arnold through Marshall.* But after the spring of 1943 the final decisions increasingly were reached by an organization in which, at every echelon, Arnold or his representatives had to be dealt with directly. Not only that, but the transfer of power to a joint staff in which Arnold had an equal voice with the other two chiefs encouraged practices that made of the AAF an independent agent for the execution of JCS decisions.

In this last development it would be difficult to exaggerate the significance of the fact that the AAF had its own independent combat mission to perform. The strategic bombardment of Germany undertaken by the Eighth Air Force had no place in U.S. war plans except as a preliminary to an amphibious invasion of western Europe. Moreover, it was well understood that the strategic forces committed to this preliminary air phase of the offensive against Germany would pass at an appropriate time to the command of the officer responsible for the invasion. Indeed, the Eighth Air Force had been set up in 1942 with an organization in which Eaker's VIII Bomber Command was balanced by an air support command for tactical operations in support of ground troops, and the whole air force had come as a matter of course under Eisenhower's command upon his assignment to the European theater in the summer of 1942. But Eisenhower was sent against the Germans in Africa (TORCH) in the fall of that year as a result of decisions which indefinitely postponed a cross-Channel attack on western Europe. Only the somewhat depleted Eighth Air Force remained in Britain to fulfill an earlier hope that Germany might be subjected to an immediate and direct attack. Though the AAF had strongly opposed the decision in favor of the landing in northwest Africa, it nevertheless gained an advantage by it. At the Casablanca conference in January 1943 the CCS, while deciding on an invasion of Sicily as the logical sequel to TORCH, authorized a combined bomber offensive by the Eighth Air Force and RAF Bomber

* See again the procedures followed in the discussion of antisubmarine warfare, as presented in Vols. I and II.

--54--

Command against Germany, and for its direction Sir Charles Portal was subsequently designated as executive for the C. In actual fact, no combined offensive, in the sense of a closely integrated RAF and AAF effort ever developed, and the Eighth Air Force's part in the campaign was run by Eaker and Arnold, and after December 1943 by Spaatz and Arnold. The Eighth Air Force passed to the control of Eisenhower on the eve of the Normandy invasion, but it was returned to the CCS in September 1944, which is to say that in effect it was returned to the AAF.*

The precedent thus established stood the AAF in good stead when the control of B-29 units came into question. Used entirely against Japan, deployment of the B-29's required no reference to the Combined Chiefs, except such as was dictated by considerations of courtesy. The question of its direction was settled by the Joint Chiefs, who made Arnold their executive agent in command of the Twentieth Air Force.† War Department regulations governing AAF activities beyond the Zone of Interior were amended in April 1944 to authorize Arnold to "implement and execute major decisions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff relative to deployment and missions, including objectives, of the Twentieth Air Force."46 AAF Headquarters assumed a dual role, with each member of Arnold's staff doing his normal job for both the Twentieth Air Force and the AAF. In fact, this was too much to expect of an already heavily laden staff, and Arnold exercised his command chiefly through a special chief of staff, who was first Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell, Jr. The experiment proved none too successful, and the command of B-29 operations passed in the summer of 1945 to the U.S. Army Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific under Spaatz. General Spaatz had commanded the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe from January 1944 until after V-E Day, a command joining administrative control of the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces in England and western Europe with operational control of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces, the latter of which operated from Mediterranean bases. Thus, by JCS and CCS decisions which Arnold helped to shape, the AAF had won a high degree of independence in the direction of strategic air operations.

* The story is recounted in detail in Vols. I, II, and III. It should be noted that after September 1944 Spaatz shared with Portal the assignment as executive of the CCS in the development of strategic bombing against Germany.

† See Vol. V, Chap. 2.

--55--

These developments created a multitude of twilight zones in which the interpretation of traditional responsibilities proved difficult. In Washington there were questions that had to be ironed out with other Army agencies, especially OPD; in the combat theaters the AAF's tendency toward an increasing selfsufficiency produced comparable difficulties over questions of bases and supply as well as of operational control. It would be hard to make any general statement on how these problems were resolved, without serious injury to the common war effort, except that the helpful personal relationships existing between air and other commanders, as with Eisenhower and Spaatz or MacArthur and Kenney, played an especially significant part. And to this might be added one other statement: organizational relations overseas were powerfully influenced by those at home.

Arnold from the very beginning had enjoyed a right of direct communication with his air commanders on technical air force problems, a terminology which became subject to a broadening interpretation. Operating his own message center in the Pentagon and possessing in every plane taking off from Washington for an overseas destination a channel of direct and informal communication with his combat commanders, he could notify them immediately of JCS and CCS decisions and could make suggestions for action. As early as October 1943 the AAF had been authorized, on OPD's recommendation, to take directly to the JCS any matter "which the Commanding General, Army Air Forces desires to transmit directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in his capacity as a member of that committee."47 The new procedure saved much time and trouble by contrast with the old, which required routing through OPD, but it set the stage for a relationship between that organization and AAF Headquarters that has been well described by the historian of OPD as depending upon "the principle of opportunistic exploitation of any and all channels leading to joint decisions."48 Similarly, the delays which naturally developed in any attempt at a three-way coordination of papers among JCS, AAF, and OPD agencies encouraged the air force to "proceed on its own authority to deploy AAF units to meet strategic requirements."49 OPD protested more than once, and any AAF officer carrying a routine paper, especially if its purpose was to further his own interest, ignored the standard procedures at some risk. But it was clear enough that Arnold himself could act on his own, and that coordination with OPD and other War Department agencies was ever becoming more of a question of mere courtesy.

--56--

The year 1943 is so obviously the turning point in these developments that it may be worth noting another victory the AAF gained on 21 July of that year. In a new field manual (FM 100-20, Command and Employment of Air Power) the War Department made official a doctrine already adapted from Brirish experience in the Middle East to the requirements of air combat in northwest Africa. "Land power and air power," read the new manual, "are coequal and interdependent forces: neither is an auxiliary of the other." This doctrine thereafter exercised a growing influence on the spirit of War Department administration.

Operating Agencies

Although after 1943 the AAF's major concern was with combat operations, its first task, and one that had a continuing importance, was to provide the air combat forces to be employed overseas. Considered in its simplest terms, this task involved the recruitment of hundreds of thousands of young men with a natural aptitude for a very wide variety of technical assignments, and the procurement in sufficient quantity of aircraft and other special equipment that could measure up to increasingly high standards of performance. After these steps, both of which were of fundamental importance, lay the jobs first of training and then of organizing trained personnel into effective combat teams skilled in the use of their intricate technical weapons. The weapons, moreover, required elaborate provision for their maintenance, and other thousands of men had to be trained and organized for that purpose. Still others had to be prepared, as in any military arm, for the performance of housekeeping and supply functions.

The nature of air operations placed a special premium on the acquisition of individual skills. An air cadet had first to be taught to fly a plane, and the first phase of training was accurately described as individual training. But air combat by the time of World War II had passed far beyond the primirive stage in which success depended heavily upon individual exploits. This war, by contrast with its predecessor, produced few individual "aces," and those few established their claims for the most part in the earliest days of combat, when a handful of men and planes fought desperately for survival. Thereafter, the accent fell on teamwork. Whether the mission was flown in squadron strength or in numbers as high as a thousand planes, the price of survival was cooperation. For the achievement of this teamwork it was necessary to put many hours into advanced, or unit, training

--57--

and to build an organization as intricate and as flexible as the weapon it employed.

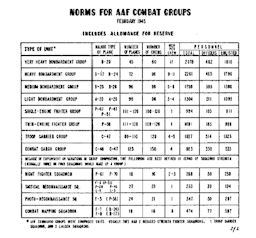

The very flexibility which characterized air force organization, not to mention its novelty by comparison with the more or less traditional structures of older services, may justify at this point some attempt to define the units out of which air combat forces were constructed. This can be done only at the risk of some oversimplification, for air organization was at all levels extraordinarily variable. The most elementary unit was the aircrew, which could mean one versatile pilot in a fighter plane or eleven men working together in a B-29 bomber.50 To simplify tactical control, planes might be organized as required into flights of three or more aircraft operating under a flight leader. Such flights normally would be formed from a single squadron, which was the basic permanent organization of AAF combat elements, and which served also as a basic organization for supporting services. The composition of a squadron varied with its mission. Though bearing a numerical designation, as did virtually all AAF organizations up to and including the combat air force, the squadron was further described by function, as in the 36th Bombardment Squadron, the 378th Fighter Squadron, the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron, the 111th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, the 21st Weather Squadron, the 422d Night Fighter Squadron, or the 46th Air Service Squadron. Bombardment squadrons were usually further distinguished, according to their equipment, by indication as to whether they were light, medium, heavy, or very heavy bombardment units. Most squadrons operated as part of a group which usually combined three or four squadrons of like function and equipment, but the squadron could and often did operate separately. Moreover, at times so-called composite groups including squadrons of different functions and equipment were formed. Tables of organization set norms for squadron strength according to requirements for the job assigned, but actual strengths differed from theater to theater and from time to time. Combat air squadrons normally had a total strength of from 200 to 500 men. In 1944 plane strength per squadron varied from seven B-29's to twenty-five fighter planes plus reserves,51 but what the "book" called for often differed widely from what a squadron might actually have. The group, which may be considered as roughly parallel to an Army regiment, was the key unit both for administrative and operational purposes, as is suggested by the fact that the AAF used this unit as the yardstick for

--58--

measuring its successive programs of expansion.* By 1945 a group normally had a personnel strength of about 990 officers and men for a single-engine fighter group, or 2,260 for a heavy bomber group. Norms for major types are indicated on an accompanying chart. The group's squadrons usually had done their more advanced training together, and they normally fought as a unit.

Before the war the wing had served as the key tactical and administrative organization through which the GHQ Air Force directed its combat forces. The wing continued to have some utility

during the war, primarily for purposes of tactical control, but the functionally conceived command, whose development seems to reflect another influence of RAF patterns on AAF organization, came to be the chief agency for coordination of effort between a top air commander and the groups making up his force.† Thus, Headquarters,

* Although the group was the yardstick for AAF plans in World War II, more recently wings have been used to describe Air Force goals. The wing plan was adopted in 1947 to unify control at air bases. A modem wing consists of a combat group plus a maintenance-supply group, an air base group, and a medical group. In other words, it is a group plus supporting units operating under the unified command of the wing. Usages have not yet been standardized, however. (See AAF Reg. 20-15, 27 June 1947.)

† In the postwar period the command was put on a higher level. It is now superior to an air force, rather than a subordinate unit as in World War II. Thus in April 1951 the Strategic Air Command had three air forces assigned to it.

--59--

AAF depended upon a series of commands in such areas as training, air service, and air materiel to execute its several programs of expansion. For the performance of comprehensive combat missions the practice was to set up distinct air forces comprising such subordinate commands as were considered necessary. Usually, there would be at least a bomber, fighter, and air service command. Numbered more or less in the order of their activation, there were before the end of the war no fewer than sixteen different air forces, four of which were retained in the United States.

It would be a mistake to assume that all air forces or commands

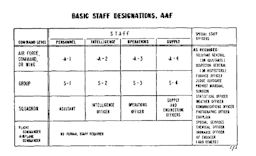

conformed to a single pattern. AAF Headquarters exerted some influence on the organization of subordinate agencies, partly by its example and partly through the establishment of basic T/O's for all air force organizations. But few limitations operated to restrict the power of any commander to accomplish his task as he saw fit with the strength assigned to him, and the internal structure of his command might vary greatly in response to a number of factors, including the personality of the commander himself. Following traditional Army usage, headquarters organizations tended to copy the old "S" and "G" staffs, which in the AAF became "A" staff sections. Air forces collaborating with the RAF at rimes experimented with deputy commanders in lieu of the older chief of staff. The U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, on its establishment in January 1944, tried the so-called "double deputy" type of organization by which staff work was consolidated under two divisions, one for

--60--

operations and one for administration.* AAF Headquarters itself acquired a deputy commander before the end of hostilities, a post held by Eaker on his return from the Mediterranean Theater of Operations in 1945. The older idea of directorates, though abandoned in 1943 by AAF Headquarters, continued to enjoy some favor, with a tendency toward adoption of a "three directorate" plan. The directors were not deputy commanders but coordinating division chiefs, who headed staff divisions for operations and training, for personnel and administration, and for supply and maintenance.52 This plan was tried by the Continental Air Forces when it was established late in the war.

In addition to its own organizations, the AAF depended upon a variety of units which operated, so to speak, on loan from other arms and services. Differing widely in function and size of organization, these units represented the chemical, engineering, finance, medical, police, ordnance, quartermaster, and signal services of the Army. Some of them were specifically organized and trained for duties peculiar to air force needs, as with an engineer aviation battalion or a chemical maintenance company (aviation); some of them, such as the Military Police or representatives of the Finance Department, performed merely the familiar duties rendered all other parts of the Army. Taken in total, they fall under no more specific classification than the rather clumsy official designation of Arms and Services with the AAF (ASWAAF). Their functions were of a kind that caused them to work more closely with the AAF's service organizations than any other, and within the United States the responsibility for their organization and training, insofar as it belonged to the AAF, fell most heavily on the Air Service Command.53 Their presence, with separate insignia and a continuing obligation to the technical service they represented, served to remind all parties that as yet the AAF, however autonomous it might be, did not have separate status. Their special position, moreover, was related to questions of fundamental importance involving control of activities on domestic airdromes. Beginning in the summer of 1943 the AAF, arguing chiefly the administrative advantages to be gained, undertook to get full integration into the air force of all ASWAAF personnel. The War Department gave its approval in the fall of 1943, but the

* See Vol. II, 773.

--61--

changeover had not been completed even at the end of the war.*